Significance

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is the most aggressive form of breast cancer and patients exhibit high rates of recurrence and mortality in part due to lack of treatment options beyond standard-of-care chemotherapy regimens. In the subset of TNBCs that express estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), ligand-mediated activation of ERβ elicits potent anticancer effects. We report here the elucidation of the ERβ cistrome and transcriptome in TNBC and identify a mechanism whereby ERβ induces cystatin gene expression resulting in inhibition of canonical TGFβ signaling and a blockade of metastatic phenotypes. These findings suggest that ERβ-targeted therapies represent a treatment option for the subset of women with ERβ-expressing TNBC.

Keywords: breast cancer, estrogen receptor beta, cystatin, TGFβ, metastasis

Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for a disproportionately high number of deaths due to a lack of targeted therapies and an increased likelihood of distant recurrence. Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), a well-characterized tumor suppressor, is expressed in 30% of TNBCs, and its expression is associated with improved patient outcomes. We demonstrate that therapeutic activation of ERβ elicits potent anticancer effects in TNBC through the induction of a family of secreted proteins known as the cystatins, which function to inhibit canonical TGFβ signaling and suppress metastatic phenotypes both in vitro and in vivo. These data reveal the involvement of cystatins in suppressing breast cancer progression and highlight the value of ERβ-targeted therapies for the treatment of TNBC patients.

In the United States, breast cancer is the second most common cancer among women and is responsible for over 40,000 deaths each year (1). As with all cancers, breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease composed of genomically distinct subtypes defined clinically by the presence of three key biomarkers: estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), the progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (2, 3). Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for 10–20% of all breast cancers and is defined by the absence of these three biomarkers (4). TNBC typically presents in younger women, is more prevalent in individuals of African American and Hispanic ancestry, and is clinically unique due to its aggressive and metastatic nature (2, 4–7). The standard of care for early stage TNBC patients includes chemotherapy, most commonly delivered before surgery. For patients with residual disease after chemotherapy, upward of 50% will develop recurrent disease (8) and nearly all patients who develop metastases succumb to their disease. For these reasons, identifying novel therapeutic strategies for these patients is of critical importance.

Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) is highly expressed in normal breast tissue; however, during the process of breast carcinogenesis, ERβ levels typically decrease (9–15). In cohorts of women with breast cancer, tumoral ERβ expression is associated with smaller tumor size, lymph-node negativity, and lower histological grade (16, 17), supporting a tumor-suppressive role for this hormone receptor. ERβ has also been shown to decrease proliferation and to inhibit epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in TNBC cells (18–22).

Using an antibody validated in a number of laboratories (23–26), we and others have identified that 30% of TNBCs express ERβ (21, 27, 28). ERβ expression in TNBC is associated with prolonged disease-free survival and overall survival relative to patients with ERβ-negative disease (27). These findings indicate that therapeutically targeting ERβ is a relevant strategy that should be further explored for TNBC patients. However, the mechanisms by which ERβ elicits tumor-suppressive effects in TNBC are not well understood. Such information is critical for monitoring response to therapy and for identifying subsets of patients who are most likely to benefit from ERβ-targeted therapies.

Results

Identification of the ERβ Cistrome in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells.

Given our previous findings that ∼30% of all TNBCs express ERβ and that estrogen (E2) treatment of ERβ-expressing TNBC cell lines substantially inhibits cell growth (21), we first sought to assess the distribution of ERβ expression among the known molecular subtypes of TNBC: basal-like 1 and 2, mesenchymal and luminal androgen receptor (29). Using a cohort of TNBC patients extensively characterized at the DNA and RNA level (30), our data suggest that ERβ is expressed across all TNBC subtypes (SI Appendix, Table S1).

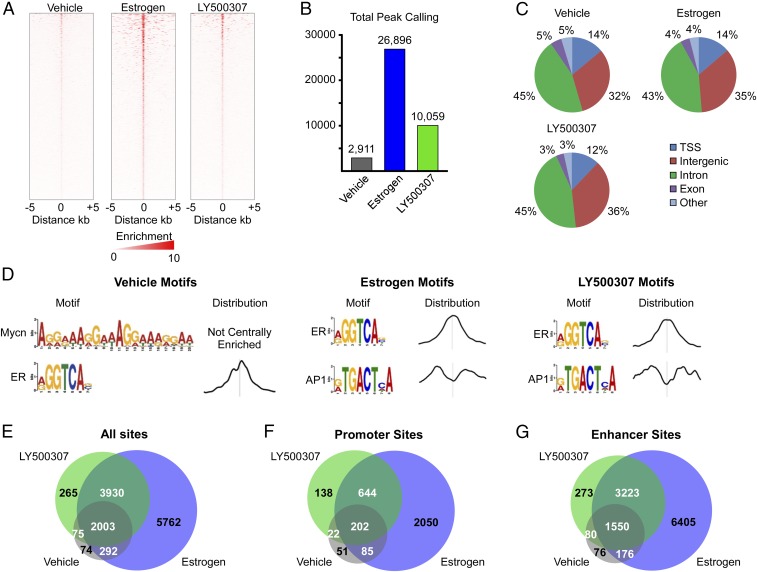

We then sought to elucidate the mechanisms by which ERβ elicits its tumor-suppressive effects in TNBC cells. As a first step, we utilized ChIP-Seq to delineate the ERβ cistrome in MDA-MB-231 cells that stably express ERβ following 3 h of treatment with ethanol vehicle, 1 nM E2, or 10 nM LY500307, an ERβ-selective agonist. Results of these studies identified 2,911 ligand-independent ERβ-binding sites in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells (Fig. 1 A and B). A total of 26,896 and 10,059 sites were identified following E2 and LY500307 treatment, respectively (Fig. 1 A and B). ERβ-binding sites were distributed throughout the genome with the majority of sites localizing within introns followed by intergenic regions and transcriptional start sites (Fig. 1C). Very few ERβ-binding sites were localized within exons (Fig. 1C). Ligand-independent ERβ-bound chromatin regions showed significant enrichment of N-Myc and ER motifs, while the top two motifs enriched within both E2- and LY500307-induced ERβ-binding sites were ER and AP1 response elements (Fig. 1D). Comparison of all ERβ-bound chromatin regions in vehicle-, E2-, and LY500307-treated cells demonstrated that nearly all of the ligand-independent binding sites were also identified in ligand-treated cells (Fig. 1E). As expected, nearly all of the LY500307-induced ERβ-binding sites were conserved within the sites identified following E2 treatment (Fig. 1E). However, 5,762 ERβ-bound regions were present only following E2 treatment (Fig. 1E). Similar patterns were observed when comparing ERβ-bound regions that were located specifically within gene promoters and enhancers (Fig. 1 F and G).

Fig. 1.

Identification of the ERβ cistrome in MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells. (A) Heat map of ERβ tag densities in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells treated with vehicle, estrogen, or LY500307 for 3 h. (B) Total peaks called for each treatment. (C) Global distribution of binding sites among treatments. TSS, transcriptional start site. (D) Top two motifs identified, and their peak distributions, for each condition. Venn diagrams indicating overlap of all binding sites (E), promoter region-specific binding sites (F), and enhancer regions (G) between treatment conditions.

ERβ-Mediated Gene Expression Profiles in TNBC Cells.

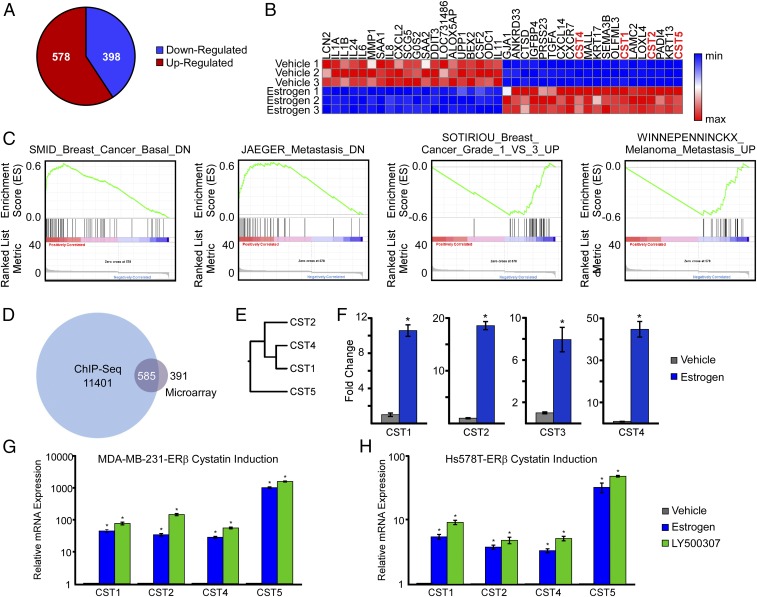

In parallel with the ChIP-Seq experiments, we sought to characterize changes in the gene expression profiles of MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells following E2 treatment. Microarray analyses were performed using Illumina HT-12 BeadChips, and the complete list of genes that met a P value ≤ 0.05 and an absolute fold change of 1.5 cut off between vehicle and E2-treated cells is provided in SI Appendix, Table S2. In total, 976 genes were differentially expressed in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells following estrogen treatment, with 578 genes being up-regulated and 398 genes down-regulated (Fig. 2A). Heat map analysis of the top 20 most induced and repressed genes following E2 treatment is depicted in Fig. 2B. Multiple interleukins and other inflammation-related factors were enriched in the group of genes shown to be the most inhibited by E2 treatment while four members of the cystatin superfamily of cysteine proteases were among the top 20 most estrogen-induced genes (Fig. 2B). Confirmation of the microarray dataset was performed using genes chosen at random (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). A Venn diagram was constructed to reveal the overlap between the ChIP-Seq and microarray results (Fig. 2D). Once replicate genes (i.e., genes containing multiple ERβ-binding sites) were removed from the ChIP-Seq dataset, a total of 11,401 genes were assigned as being associated with at least one ERβ-binding site. Of the 976 genes shown to be regulated by estrogen treatment, 585 were shown to have a nearby ERβ-binding site (Fig. 2D). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using a preranked gene list comprising the 976 genes identified in the microarray analysis, and it revealed significant associations with phenotypes pertaining to breast cancer grade and cancer metastasis (Fig. 2C). Specifically, genes induced by E2 in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells were also shown to exhibit increased expression in nonbasal-like breast cancer, low-grade breast cancer, and nonmetastatic cancers (Fig. 2C). All four of the cystatins shown to be induced by estrogen in ERβ-expressing cells were found at the leading edge of each of the gene sets identified by GSEA. A dendrogram depicting the relationship between cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5 within the cysteine protease family is shown in Fig. 2E as well as their expression levels in vehicle- and estrogen-treated MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells as determined by microarray analysis (Fig. 2F). Regulation of cystatin gene expression by E2 was confirmed by RT-PCR in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells, as well as in a second ERβ-expressing TNBC cell line (Hs578T), and compared with the effects elicited by the ERβ-selective agonist LY500307 following 5 d of treatment (Fig. 2 G and H). In both models, all four cystatins were significantly induced by estrogen and LY500307, and there were no appreciable differences between the two ligands. However, the fold-increase for all four cystatin genes was ∼10-fold less in the Hs578T-ERβ cells (Fig. 2 G and H). To examine the basis for this difference, we first assessed the basal expression levels of the four cystatins between these two cell lines in the absence and presence of doxycycline (dox) treatment. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, the basal expression levels of the cystatins were extremely low in the absence of dox in both cell lines. Following dox treatment, the expression levels increased approximately twofold in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells and 10- to 50-fold in Hs578T-ERβ cells. Interestingly, ERβ mRNA levels following dox treatment were actually 10-fold lower in Hs578T-ERβ cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), suggesting that the apparent differences in cystatin induction by ERβ in these two models is explained by the more robust ligand-independent effects observed in the Hs578T-ERβ cell line.

Fig. 2.

ERβ-regulated gene expression signatures in TNBC cells. (A) Pie chart depicting the number of estrogen-regulated genes in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells following 5 d of treatment. (B) Heat map depicting expression levels of the top 20 most highly up- and down-regulated genes following estrogen treatment. (C) GSEA of the microarray data indicating associations of ERβ-specific gene signatures with multiple cancer-related phenotypes. (D) Venn diagram indicating overlap between genes identified as having nearby ERβ-binding sites via ChIP-Seq and genes significantly regulated by estrogen treatment from the microarray datasets. (E) Dendogram indicating relationship of cystatins identified to be significantly up-regulated by ERβ in response to estrogen treatment. (F) RT-PCR confirmation of the microarray data for cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5 in response to estrogen treatment of MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. (G and H) Independent RT-PCR confirmation of cystatin induction following 1 nM E2 or 10 nM LY500307 treatment for 5 d in MDA-MB-231-ERβ and Hs578T-ERβ cells. Data are represented as average ± SEM; *P < 0.05 relative to vehicle-treated control cells.

Cystatins Are Highly Induced by ERβ and Correlate with Relapse-Free Survival in TNBC.

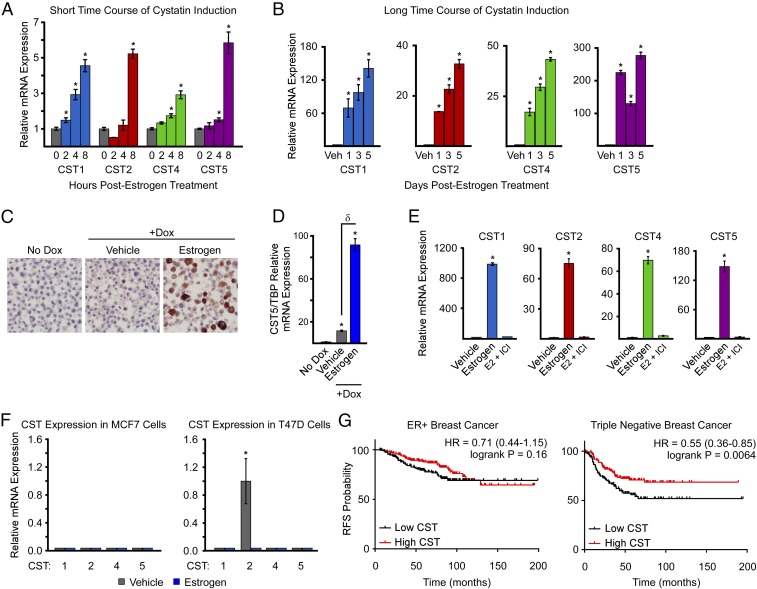

Given the above findings, we next performed a time-course analysis of cystatin gene expression following E2 treatment of MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. Cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5 were shown to be significantly induced by E2 within 2–8 h of exposure (Fig. 3A) and continued to increase during extended treatment times of 1–5 d (Fig. 3B). To confirm these findings at the protein level, immunohistochemistry for the most highly induced cystatin, cystatin 5, was performed in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cell-line pellets. Cystatin 5 staining was absent in vehicle-treated cells, slightly positive following dox-induced ERβ expression, and highly positive in the setting of E2 treatment (Fig. 3C). These ligand-independent effects of ERβ on cystatin gene expression were confirmed at the mRNA level, where dox treatment of MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells was shown to significantly induce the expression of cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5 relative to no-dox–treated cells even in the absence of a ligand (Fig. 3D). In addition, the E2-mediated induction of cystatin 1, 2, 4, and 5 expression was completely abolished by the pure anti-estrogen fulvestrant (ICI 182,780) (Fig. 3E). To determine if the induction of cystatins by E2 was unique to ERβ, we also analyzed their expression levels in ERα+ MCF7 and T47D breast cancer cells after 24 h of treatment (Fig. 3F). Cystatins 1, 4, and 5 were completely undetectable by RT-PCR in both MCF7 and T47D cells while cystatin 2 demonstrated basal expression in T47D cells that was repressed with estrogen treatment (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, estrogen treatment of ERα-expressing MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells had no effect on the expression levels of cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5 with the exception of a slight induction of cystatin 1 in the MDA-MB-231 model (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). To determine the potential relevance of these cystatins in breast cancer, we examined their association with patient outcomes using the online Kaplan–Meier plotter program in the breast cancer dataset (31). Using the multigene classifier for cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5, high cystatin expression was significantly associated with improved relapse-free survival (RFS) in TNBC patients but not in ER+/PR+ patients (Fig. 3G). Together, these data indicate that cystatins are highly induced by E2 in an ERβ-specific manner and are positively correlated with improved RFS in TNBC patients.

Fig. 3.

ERβ-specific regulation of cystatins in TNBC cells. (A and B) RT-PCR analysis of cystatin 1, 2, 4, and 5 expression levels following estrogen treatment of MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells for indicated times. (C) Immunohistochemistry analysis of cystatin 5 protein levels in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cell pellets treated as indicated for 5 d. Images were taken at 40× magnification. (D) mRNA expression levels of cystatin 5 as detected by RT-PCR in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells treated as indicated for 5 d (E) RT-PCR analysis demonstrating blockade of estrogen-induced cystatin gene expression by the pure anti-estrogen ICI. (F) RT-PCR analysis of cystatin expression levels in ERα-positive MCF7 and T47D cells following vehicle and estrogen treatment for 24 h. (G) Kaplan–Meier plots depicting RFS as a function of high and low cystatin 1, 2, 4, and 5 expression levels in ER/PR-positive breast cancer vs. TNBC. Data are represented as average ± SEM; *P < 0.05 relative to vehicle-treated control cells. δP < 0.05 between indicated treatments.

Direct Regulation of Cystatin Gene Expression by ERβ.

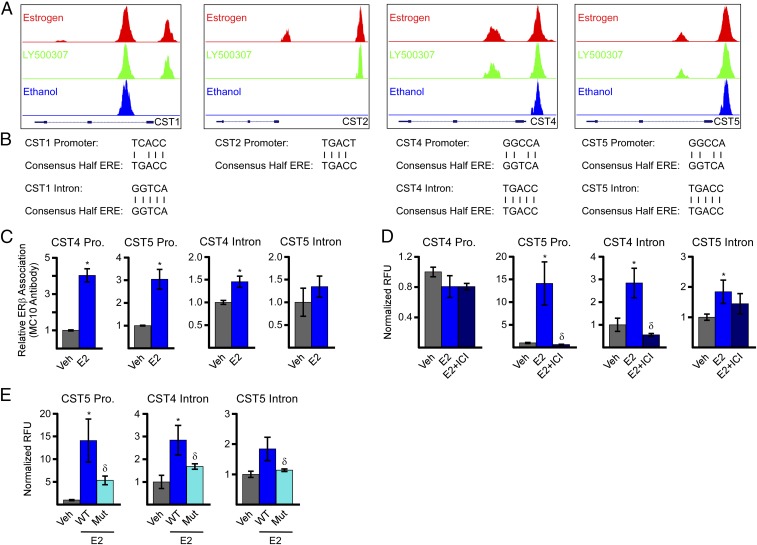

To identify the mechanisms by which ERβ induces cystatin gene expression, we interrogated the ChIP-Seq data and identified ERβ-bound regions within the promoter of all four cystatins as well as the first intron of cystatins 1, 4, and 5 (Fig. 4A). An ERβ-bound region far upstream of the transcriptional start site of cystatin 2 was also indicated (Fig. 4A). ERβ was shown to be associated with the promoter of cystatins 4 and 5 both in the absence and presence of a ligand, while its association with the cystatin 1 and 2 promoters was ligand-dependent (Fig. 4A). ERβ association with intron 1 was also ligand-dependent for cystatins 4 and 5 but ligand-independent for cystatin 1 (Fig. 4A). These binding sites were centered over estrogen response elements (EREs), and a schematic showing the homology of a consensus ERE with the identified cystatin-specific EREs is shown in Fig. 4B. ChIP-PCR using the ERβ-specific MC10 antibody was used to confirm ERβ association with selected EREs (Fig. 4C). Given the nearly identical sequence homology between cystatins 1, 2, and 4, and their divergence from cystatin 5, we focused on cystatins 4 and 5 in subsequent analyses. E2 treatment was shown to enhance ERβ association with the cystatin 4 and 5 promoters with only a trend toward increased binding in the setting of E2 on the ERE within intron 1 of cystatin 5 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Identification of ERβ regulatory elements responsible for mediating estrogen-induced expression of cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5. (A) Screen shots from the University of California at Santa Cruz genome browser of ERβ signals from ChIP-Seq experiments on the promoters and first introns of indicated cystatin genes in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. (B) Comparison of a consensus ERE half-site to the EREs identified in the promoters and first introns of cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5 via ERβ ChIP-Seq. (C) ChIP-PCR confirmation of ChIP-Seq data for indicated sites following pulldown with an ERβ-specific antibody (MC10) in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. (D) Luciferase assays indicating basal and estrogen-induced (24 h) activity of indicated cystatin promoter and intronic regions encoding identified ERβ-binding sites in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. (E) Luciferase assays depicting the estrogen-mediated activity of indicated cystatin promoter and intronic elements following site-directed mutagenesis of the identified EREs relative to wild-type controls. Data are represented as average ± SEM; *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle-treated control cells. δP < 0.05 compared with estrogen-treated cells. Pro, promoter.

To assess the activity of the identified EREs, a 500-bp region centered on the ERβ-binding site in the cystatin 4 and 5 promoter and first intron was cloned into a luciferase reporter construct. With the exception of the cystatin 4 promoter construct, E2 treatment was shown to induce luciferase activity following transfection into MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells, effects that were completely abolished by ICI (Fig. 4D). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to eradicate the EREs identified in the cystatin 5 promoter and cystatin 4 and 5 introns. Mutation of these EREs was also shown to abolish estrogen-induced luciferase activity (Fig. 4E), confirming the involvement of these sites in ERβ-mediated induction of cystatin gene expression.

Biological Effects of Cystatins in TNBC Cells.

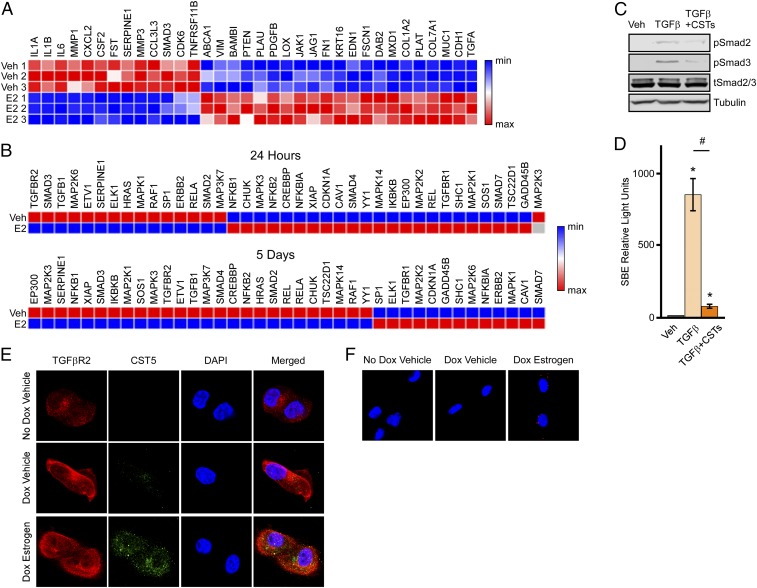

Given these findings, we sought to better understand the potential biological effects of cystatins in TNBC cells. Ingenuity pathway analysis of our microarray data revealed significant changes in multiple canonical signaling pathways (SI Appendix, Table S3). The top pathway identified pertained to fibrosis and consisted of numerous genes known to be involved in TGFβ signaling. Furthermore, upstream regulator analysis identified core components of the TGFβ-signaling pathway including Smad4 and TGFβ1 (SI Appendix, Table S4), suggesting that ligand-mediated activation of ERβ impacts the TGFβ-signaling pathway in TNBC cells. Based on these findings, we constructed a heat map consisting of known TGFβ pathway genes from the microarray data (Fig. 5A). We also examined the effects of 24 h or 5 d of estrogen treatment on the TGFβ-signaling pathway using a TGFβ pathway PCR array. These data confirmed that estrogen treatment of ERβ-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells significantly alters the expression of multiple genes within the canonical TGFβ pathway (Fig. 5B). To determine if estrogen-mediated induction of cystatins impacted TGFβ signaling, we next analyzed the phosphorylation levels of Smad2 and Smad3 following TGFβ stimulation in the presence and absence of a combination of recombinant cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5. Pretreatment of non-ERβ–expressing parental MDA-MB-231 cells with recombinant cystatins resulted in a blockade of Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation by TGFβ (Fig. 5C). In parallel, recombinant cystatins were also shown to suppress the ability of TGFβ to induce a Smad-binding element luciferase reporter construct (Fig. 5D), demonstrating that cystatins inhibit TGFβ signaling. Interestingly, TGFβR2 and cystatin 5 were shown to colocalize in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells following E2 treatment (Fig. 5E). An interaction between cystatin 5 and TGFβR2 in the setting of estrogen treatment was confirmed using a Duolink proximity assay as indicated by the punctate red staining (Fig. 5F). Taken together, these data indicate that cystatins interact with TGFβR2 to inhibit canonical TGFβ signaling in TNBC cells.

Fig. 5.

Estrogen- and cystatin-mediated regulation of canonical TGFβ signaling in TNBC cells. (A) Heat map analysis of known TGFβ pathway genes shown to be differentially regulated by estrogen treatment in MDA-MB-231-ERβ–expressing cells. (B) Heat maps generated from a TGFβ qPCR array indicating the effects of 24 h or 5 d of estrogen treatment on indicated genes in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. (C) Western blot for phospho-Smad2, phospho-Smad3, total Smad2/3, and tubulin in MDA-MB-231 cell extracts. Cells were pretreated with a combination of recombinant cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5 for 6 h followed by TGFβ (2 ng/mL) or vehicle treatments for 30 min. (D) Luciferase assays indicating the activity of a Smad Binding Element reporter construct in parental MDA-MB-231 cells treated as indicated. Data are represented as average ± SEM; *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle-treated control cells. #P < 0.05 compared with TGFβ-treated cells. (E) Immunofluorescent analysis of TGFβR2 (red) and cystatin 5 (green) proteins in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells treated as indicated for 24 h. Representative images are shown at 20× magnification. (F) Proximity-based Duolink assay indicating interaction between cystatin 5 and TGFβR2 proteins (red dots) in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells treated as indicated for 24 h. Representative images are shown at 20× magnification.

ERβ-Mediated Induction of Cystatins Inhibits TNBC Cell Invasion and Migration.

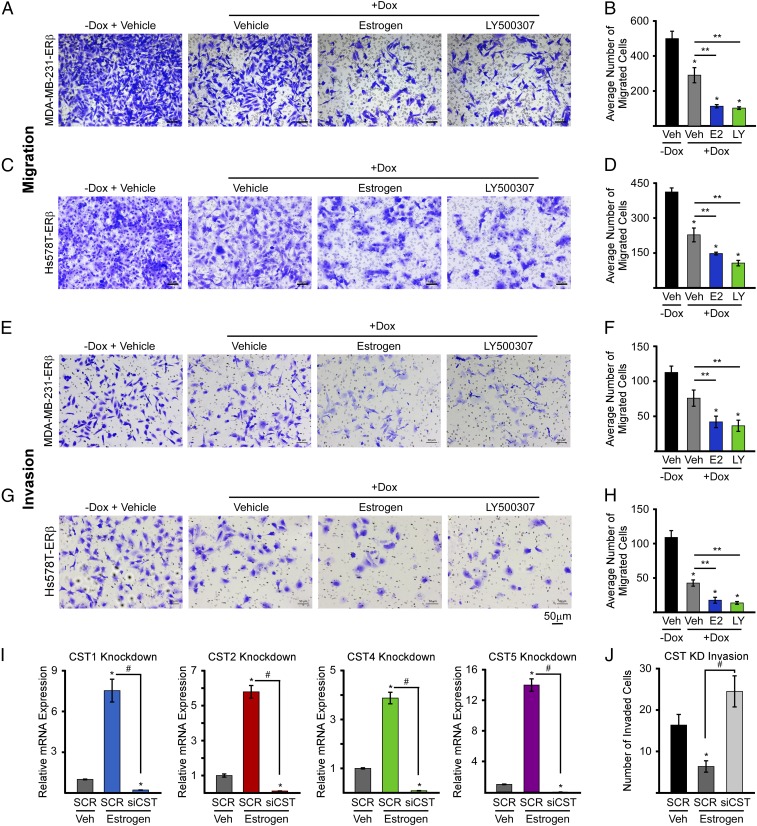

In light of the invasive and migratory properties of TNBC, and the known roles of TGFβ signaling in driving breast cancer cell invasion and migration (32–35), we analyzed the impact of ERβ on these cellular properties. Invasion and migration of MDA-MB-231-ERβ and Hs578T-ERβ cells were analyzed using transwell assays following treatment with no-dox vehicle control, dox vehicle, dox + 1 nM estrogen, or dox + 10 nM LY500307. Dox-induced expression of ERβ resulted in suppression of both MDA-MB-231-ERβ and Hs578T-ERβ cell invasion and migration, even in the absence of a ligand (Fig. 6 A–H). These inhibitory effects were significantly magnified following treatment with either E2 or LY500307 (Fig. 6 A–H).

Fig. 6.

Cystatins mediate ERβ suppression of TNBC cell migration and invasion. Cell migration and invasion assays were performed with MDA-MB-231-ERβ and Hs578T-ERβ cell lines. Representative images following indicated treatments are shown (A, C, E, and G), and quantification of triplicate experiments ± SEM are indicated (B, D, F, and H). (I) RT-PCR analysis indicating the efficacy of cystatin 1, 2, 4, and 5 siRNAs with regard to suppressing estrogen-induced cystatin gene expression in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. (J) Effects of siRNA-mediated silencing of cystatin 1, 2, 4, and 5 expression on MDA-MB-231-ERβ cell invasion in the presence of indicated treatments. Data are represented as average ± SEM; *P ≤ 0.05 relative to −Dox/Veh controls. **P ≤ 0.01 relative to Dox/Veh cells following adjustment for multiple comparisons. #P < 0.05 compared with SCR + estrogen-treated cells. (Scale bars: A, C, E, and G, 50 µm.)

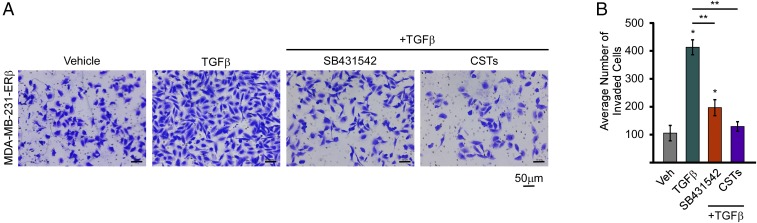

Since cystatins are secreted proteins that are highly induced by ERβ and are capable of inhibiting canonical TGFβ signaling, we sought to determine their ability to suppress TNBC cell invasion. siRNA-mediated knockdown was optimized for each individual cystatin, and all siRNAs were shown to block E2-mediated induction of the cystatins in MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells (Fig. 6I). Combinatorial knockdown of all four cystatins was shown to block the ability of E2 to suppress cell invasion (Fig. 6J). Treatment of parental MDA-MB-231 cells with recombinant cystatins was also shown to completely suppress TGFβ-mediated invasion, effects that were significantly greater than that of a TGFβ-specific inhibitor, SB431542 (Fig. 7). Combined, these data show that ligand-mediated activation of ERβ substantially inhibits the invasive and migratory properties of TNBC cells in part through the actions of cystatins and suppression of TGFβ signaling.

Fig. 7.

Cystatins inhibit TGFβ-induced invasion in TNBC cells. (A) Representative images of parental MDA-MB-231 cell invasion assays following treatment with TGFβ ligand (2 ng/mL), TGFβ + recombinant CST proteins (125 ng/mL of each recombinant cystatin), or TGFβ + SB431542 (10 µM/mL), a TGFβ-specific inhibitor. (B) Quantification of triplicate invasion experiments ± SEM following indicated treatments. *P ≤ 0.05 relative to vehicle-treated control cells. **P ≤ 0.01 relative to TGFβ-treated cells following adjustment for multiple comparisons.

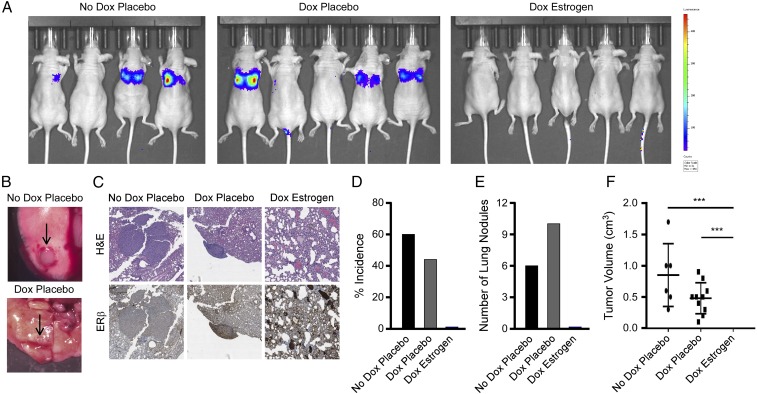

ERβ Activation Prevents Lung Metastasis of MDA-MB-231 Cells in Vivo.

A common site of TNBC metastasis is the lung; therefore, we sought to determine the effect of ERβ activation on the ability of TNBC cells to establish lung colonization in vivo as a model of metastasis. MDA-MB-231-ERβ-Luc cells were injected into the tail veins of ovariectomized athymic nude mice and randomized to one of three treatment arms: normal chow/placebo pellet, dox chow/placebo pellet, or dox chow/estrogen pellet with eight mice in each group. Mice were monitored for the development of lung metastases via IVIS2000 xenogen imaging. Representative images from animals in each treatment arm are shown before being killed (Fig. 8A). Following being killed, metastatic lesions were quantitated in the lungs under a dissecting scope, and representative images of tumor nodules in the no-dox placebo and dox placebo groups (10× magnification) are shown (Fig. 8B). No macroscopic lung nodules were observed in any of the animals in the dox estrogen group, effects that were confirmed following histological analysis for microscopic lesions (Fig. 8C). The percentage of tumor incidence (Fig. 8D), number of lung nodules (Fig. 8E), and average tumor volume (Fig. 8F) were also evaluated for each treatment group. These studies confirm the in vitro findings presented above and demonstrate that ligand-mediated activation of ERβ is capable of preventing the development of metastatic lesions in vivo.

Fig. 8.

Estrogen treatment inhibits lung colonization of ERβ-positive TNBC cells. MDA-MB-231-ERβ-luciferase cells were injected into ovariectomized nude mice via the tail vein and randomized to indicated treatments. (A) The IVIS2000 xenogen imaging indicating the presence of lung metastasis in mice randomized to the no-dox placebo and dox placebo groups but not in the dox estrogen group. (B) Gross images of metastatic breast cancer nodules in the lung (indicated by arrows) from representative animals in the indicated treatment groups (10× magnification). (C) Representative images depicting histological analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded mouse lungs from animals in each treatment group following H&E staining and immunohistochemical analysis for ERβ at 40× magnification. Quantification of the incidence of lung nodules (D), the number of lung nodules (E), and the tumor volume of lung nodules (F) in mice randomized to the indicated treatment groups. ***P ≤ 0.01 relative to indicated treatment groups following adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to characterize the biological effects of targeting ERβ in TNBC cells and to elucidate the mechanisms of action through which it functions in the TNBC form of the disease. We have characterized the ERβ cistrome in TNBC cells and have determined the effects of E2 on the global gene expression profiles of MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells. Microarray analysis revealed estrogen-mediated induction of a family of genes known as cystatins, and ChIP-Seq analysis identified ERβ-binding sites within the promoter and intronic regions of these genes. These ERβ-binding sites were confirmed to be occupied by ERβ and were shown to be transcriptionally active following exposure to ERβ agonists. Ligand-mediated activation of ERβ with estrogen or LY500307 resulted in decreased invasion and migration of TNBC cells in vitro and prevented the formation of lung metastasis in vivo. Taken together, we propose a mechanism through which ERβ elicits tumor-suppressive effects, particularly with regard to suppression of metastatic phenotypes, which is characterized by the induction of cystatins and the subsequent inhibition of canonical TGFβ signaling.

ChIP-Seq analysis identified nearly 30,000 ERβ-binding sites across the genome of which the large majority were ligand-dependent. Estrogen treatment of MDA-MB-231-ERβ cells resulted in significantly more enrichment of ERβ on DNA compared with the ERβ-specific agonist LY500307. This discrepancy could be a result of differential receptor conformation when these two ligands are bound and/or of alterations in cofactor recruitment. However, it is worth noting that nearly all of the LY500307-induced ERβ-binding sites were conserved among the E2-induced binding sites, suggesting that these differences could also be explained by a difference in the IC50 for these two ligands. As is the case with ERα (36, 37), the large majority of ERβ-binding sites were located in introns or intergenic regions of chromatin, indicating that ERβ primarily occupies enhancer regions across the genome.

In parallel to the ChIP-Seq studies, microarray analysis was performed to identify genes differentially regulated by ERβ following estrogen treatment. Through this analysis, we identified over 900 genes that were significantly induced or repressed and demonstrated that genes, the expression of which was up-regulated by ERβ, were associated with less aggressive breast cancer phenotypes and decreased metastatic potential. Of the most highly induced transcripts, four were members of a superfamily of genes known as the cystatins, specifically cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5. These four genes were shown to be specifically induced by E2 in an ERβ-specific manner as their expression levels were either completely absent or repressed by E2 in ERα-positive breast cancer cells and since they were not induced by estrogen in ERα-expressing MDA-MB-231 or Hs578T cells. Cystatins are small secreted proteins that have previously been shown to function as cysteine protease inhibitors (38–40). While extensive research has been performed on a closely related family member, cystatin 3 (41), relatively little is known about cystatins 1, 2, 4, and 5. Furthermore, nothing is known about the expression levels or function of these four cystatins in breast cancer.

ERβ has previously been shown to be a prognostic factor in TNBC, as high expression of this receptor is associated with improved overall survival, disease-free survival, and distant metastasis-free survival (27). Given our findings that ligand-mediated activation of ERβ results in substantial increases in cystatin gene expression in TNBC, we analyzed the association of cystatin 1, 2, 4, and 5 expression levels with relapse-free survival of TNBC patients. Intriguingly, high expression of all four cystatins correlated with improved relapse-free survival, but only in TNBC patients and not in breast cancer patients expressing ERα and PR. These findings are in agreement with the results of the present study implicating important tumor-suppressive effects of cystatins in TNBC. Furthermore, these data suggest that monitoring cystatin expression levels may have prognostic and/or predictive value in this form of the disease.

Utilizing our ChIP-Seq dataset, we were able to identify ERβ-binding sites within the promoter and intronic regions of each of the four cystatin genes shown to be induced by E2 treatment in TNBC cells. These binding sites encoded functional EREs that were activated by ERβ in a ligand-dependent manner. ERβ was also shown to occupy some of these binding sites in a ligand-independent fashion. This likely explains our findings that expression of ERβ alone, even in the absence of a ligand, is capable of causing a slight induction of cystatin gene expression. These findings demonstrate that ERβ directly associates with these regulatory elements to enhance cystatin gene expression in TNBC cells.

Although the cystatins were among the most highly regulated genes following E2 treatment of TNBC cells, it was not immediately obvious as to what effect, if any, they may have on TNBC cell biology. We therefore returned to our gene expression dataset and identified alterations in the TGFβ-signaling pathway through the use of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Furthermore, these analyses predicted that our gene expression signature correlated with decreased TGFβ ligand activity. TGFβ signaling is a known driver of metastasis, disease progression, and resistance to chemotherapy in TNBC (42, 43), and activation of TGFβ signaling is associated with worse outcomes for breast cancer patients (33, 44). Given that a previous study has linked the closely related family member cystatin 3 with decreased TGFβ pathway activity (45), we speculated that increased expression of cystatins by ERβ may result in suppression of TGFβ signaling in TNBC cells. Indeed, we demonstrated that cystatins block canonical TGFβ signaling in breast cancer cells likely due to their ability to directly interact with the TGFβR2 resulting in inhibition of TGFβ ligand occupancy.

Given that activation of the TGFβ pathway drives invasiveness in TNBC (42, 43), and in light of our findings that ERβ induces the expression of cystatins capable of inhibiting canonical TGFβ signaling, we sought to determine the effects of ERβ on TNBC cell invasion and migration. Our data demonstrate that the presence of ERβ, even in the absence of a ligand, suppresses both invasion and migration of TNBC cells, effects that are dramatically magnified by treatment with E2 or the ERβ selective agonist LY500307. ERβ-mediated inhibition of invasion and migration is dependent on the biological activities of the cystatins since suppression of cystatin gene expression reverses these effects. Furthermore, we demonstrated that cystatins are capable of blocking TGFβ-induced cell invasion, an effect that was even stronger than a TGFβ inhibitor. These in vitro effects were confirmed in an in vivo metastatic mouse model, where ligand-mediated activation of ERβ was shown to completely block lung colonization of TNBC cells.

In conclusion, our data elucidate the ERβ cistrome in TNBC and identify and characterize the functional roles of cystatins in this disease. The present report builds upon prior data that ERβ is expressed in ∼30% of TNBC patients and that ligand-mediated activation of ERβ suppresses TNBC cell proliferation (21) and tumor progression (18, 46). Our results lend further support to the notion that therapeutic targeting of ERβ may elicit clinical benefit for TNBC patients and that this effect is dependent on ERβ to induce tumoral expression of cystatins. These results lay the foundation for future studies aimed at analyzing the antitumor activity of estrogen and ERβ-selective agonists in ERβ-positive TNBC patients.

Materials and Methods

Detailed information regarding the cell lines, chemicals, reagents, and procedures utilized in these studies is described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods. All animal work was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (47). The protocol was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Permit no. A33015). For all of the human specimens used in immunohistochemical analyses, informed consent was obtained. Use of these samples was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mayo Clinic (protocol nos. 13-000585 and 11-007860).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Molly Nelson-Holte for her expertise in assisting with the animal work; Dr. Ed Leof for supplying the phospho-Smad3 antibody; Drs. Steve Johnsen and Vivek Mishra for their insight and help with the GSEA; and Dr. Rani Kalari for the statistical analysis from the Breast Cancer Genome Guided Therapy Study (BEAUTY). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health through the Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer SPORE Grant P50CA116201 (to M.P.G. and J.R.H.); the Prospect Creek Foundation (J.R.H.); the Eisenberg Foundation (J.R.H.); the Mayo Graduate School (J.M.R.); Medical Research Council Grant MR/L00156X/1 (to A.W.N.); The Urology Foundation Scholarship Grant RESCH1302 (to A.W.N.); and NIH Grant R01AR068275 (to D.G.M.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or other funding agencies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The ChIP-Seq and microarray data described in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession nos. GSE108980 and GSE108979).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1807751115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorlie T, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakha EA, et al. Prognostic markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:25–32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papa A, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: Investigating potential molecular therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:55–75. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.970176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakha EA, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: Distinguishing between basal and nonbasal subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2302–2310. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey LA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amirikia KC, Mills P, Bush J, Newman LA. Higher population-based incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer among young African-American women: Implications for breast cancer screening recommendations. Cancer. 2011;117:2747–2753. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Minckwitz G, et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1796–1804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roger P, et al. Decreased expression of estrogen receptor beta protein in proliferative preinvasive mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2537–2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dotzlaw H, Leygue E, Watson PH, Murphy LC. Estrogen receptor-beta messenger RNA expression in human breast tumor biopsies: Relationship to steroid receptor status and regulation by progestins. Cancer Res. 1999;59:529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwao K, Miyoshi Y, Egawa C, Ikeda N, Noguchi S. Quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-beta mRNA and its variants in human breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:733–736. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001201)88:5<733::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, Watson PH, Murphy LC. Altered estrogen receptor alpha and beta messenger RNA expression during human breast tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3197–3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw JA, et al. Oestrogen receptors alpha and beta differ in normal human breast and breast carcinomas. J Pathol. 2002;198:450–457. doi: 10.1002/path.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skliris GP, et al. Reduced expression of oestrogen receptor beta in invasive breast cancer and its re-expression using DNA methyl transferase inhibitors in a cell line model. J Pathol. 2003;201:213–220. doi: 10.1002/path.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao C, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor beta isoforms in normal breast epithelial cells and breast cancer: Regulation by methylation. Oncogene. 2003;22:7600–7606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizza P, et al. Estrogen receptor beta as a novel target of androgen receptor action in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:R21. doi: 10.1186/bcr3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heldring N, et al. Estrogen receptors: How do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:905–931. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanle EK, et al. Research resource: Global identification of estrogen receptor β target genes in triple negative breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1762–1775. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazennec G, Bresson D, Lucas A, Chauveau C, Vignon F. ER beta inhibits proliferation and invasion of breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4120–4130. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secreto FJ, Monroe DG, Dutta S, Ingle JN, Spelsberg TC. Estrogen receptor alpha/beta isoforms, but not betacx, modulate unique patterns of gene expression and cell proliferation in Hs578T cells. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:1125–1147. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reese JM, et al. ERβ1: Characterization, prognosis, and evaluation of treatment strategies in ERα-positive and -negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:749. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas C, et al. ERbeta1 represses basal breast cancer epithelial to mesenchymal transition by destabilizing EGFR. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R148. doi: 10.1186/bcr3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu X, et al. Development, characterization, and applications of a novel estrogen receptor beta monoclonal antibody. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:711–723. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weitsman GE, et al. Assessment of multiple different estrogen receptor-beta antibodies for their ability to immunoprecipitate under chromatin immunoprecipitation conditions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:23–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wimberly H, et al. ERβ splice variant expression in four large cohorts of human breast cancer patient tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:657–667. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3050-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson AW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of estrogen receptor beta antibodies in cancer cell line models and tissue reveals critical limitations in reagent specificity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;440:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, et al. ERβ1 inversely correlates with PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway and predicts a favorable prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152:255–269. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo L, et al. Significance of ERβ expression in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehmann BD, et al. Refinement of triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes: Implications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy selection. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goetz MP, et al. Tumor sequencing and patient-derived xenografts in the neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szász AM, et al. Cross-validation of survival associated biomarkers in gastric cancer using transcriptomic data of 1,065 patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49322–49333. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhola NE, et al. TGF-β inhibition enhances chemotherapy action against triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1348–1358. doi: 10.1172/JCI65416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bierie B, et al. Abrogation of TGF-beta signaling enhances chemokine production and correlates with prognosis in human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1571–1582. doi: 10.1172/JCI37480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giampieri S, et al. Localized and reversible TGFbeta signalling switches breast cancer cells from cohesive to single cell motility. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1287–1296. doi: 10.1038/ncb1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matise LA, Pickup MW, Moses HL. TGF-beta helps cells fly solo. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1281–1284. doi: 10.1038/ncb1109-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Ross-Innes CS, Schmidt D, Carroll JS. FOXA1 is a key determinant of estrogen receptor function and endocrine response. Nat Genet. 2011;43:27–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welboren WJ, et al. ChIP-Seq of ERalpha and RNA polymerase II defines genes differentially responding to ligands. EMBO J. 2009;28:1418–1428. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox JL. Cystatins and cancer. Front Biosci. 2009;14:463–474. doi: 10.2741/3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohamed MM, Sloane BF. Cysteine cathepsins: Multifunctional enzymes in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:764–775. doi: 10.1038/nrc1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickinson DP, Zhao Y, Thiesse M, Siciliano MJ. Direct mapping of seven genes encoding human type 2 cystatins to a single site located at 20p11.2. Genomics. 1994;24:172–175. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wegiel B, et al. Cystatin C is downregulated in prostate cancer and modulates invasion of prostate cancer cells via MAPK/Erk and androgen receptor pathways. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebrun JJ. The dual role of TGFβ in human cancer: From tumor suppression to cancer metastasis. ISRN Mol Biol. 2012;2012:381428. doi: 10.5402/2012/381428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farina AR, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 enhances the invasiveness of human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells by up-regulating urokinase activity. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:721–730. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980302)75:5<721::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buck MB, Knabbe C. TGF-beta signaling in breast cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:119–126. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sokol JP, Schiemann WP. Cystatin C antagonizes transforming growth factor beta signaling in normal and cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:183–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reese JM, et al. ERβ inhibits cyclin dependent kinases 1 and 7 in triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:96506–96521. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Research Council . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th Ed National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.