Significance

Growing evidence suggests that prominent changes in the gut microbial communities (dysbiosis) play a key role in the development of allergic disorders, but the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. Here, we used a murine model of human allergic contact dermatitis to demonstrate a regulatory role of the adaptor mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) RIG-I–like receptors on disease outcome by modulating gut barrier function and bacterial ecology. Our results highlight an unexpected role of the RIG-I–MAVS pathway in maintenance of intestinal barrier function and modulation of gut commensal flora to prevent the development of inflammatory diseases such as allergy. These data provide a rationale for manipulating the gut microbiota as a therapeutic intervention in subjects at risk of developing allergy.

Keywords: RIG-like receptors, MAVS, dysbiosis, allergic skin pathologies

Abstract

Prominent changes in the gut microbiota (referred to as “dysbiosis”) play a key role in the development of allergic disorders, but the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Study of the delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response in mice contributed to our knowledge of the pathophysiology of human allergic contact dermatitis. Here we report a negative regulatory role of the RIG-I–like receptor adaptor mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) on DTH by modulating gut bacterial ecology. Cohousing and fecal transplantation experiments revealed that the dysbiotic microbiota of Mavs−/− mice conferred a proallergic phenotype that is communicable to wild-type mice. DTH sensitization coincided with increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation within lymphoid organs that enhanced DTH severity. Collectively, we unveiled an unexpected impact of RIG-I–like signaling on the gut microbiota with consequences on allergic skin disease outcome. Primarily, these data indicate that manipulating the gut microbiota may help in the development of therapeutic strategies for the treatment of human allergic skin pathologies.

Over millions of years of coevolution, the adaptation of gut microbial communities (the microbiota) to a nutrient-rich environment has contributed to the host’s overall fitness. This mutualistic relationship influences tissue morphogenesis, metabolism, and immune development and functionality (1). The host immune–microbiota dialogue was initially described as occurring locally (2, 3), but growing evidence showed that gut microbiota may impact immune responses at distant sites (4–6). Notably, recent progress in high-throughput sequencing provided a detailed view of the exquisitely balanced architecture of the microbiota. Hence, epidemiologic studies showed that the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota influence the development of allergic diseases, including eczema (7–9). However, whether and how alterations in the gut microbiota may affect the outcome of skin allergic or inflammatory diseases remain elusive. In human, a genome-wide association study identified a susceptibility locus within the RIG-I–like (RLR) sensor MDA5 gene for the inflammatory skin disease psoriasis (10). Moreover, prominent changes in the gut microbial communities have been associated with deficiencies in innate immune pattern recognition receptors (PRR) (11, 12), and an unexpected role of the RLR common adaptor mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) pathway has been unveiled in monitoring intestinal commensal bacteria and maintaining tissue homeostasis (13).

Results

MAVS Deficiency Leads to Significant Differences in Gut Microbial Composition.

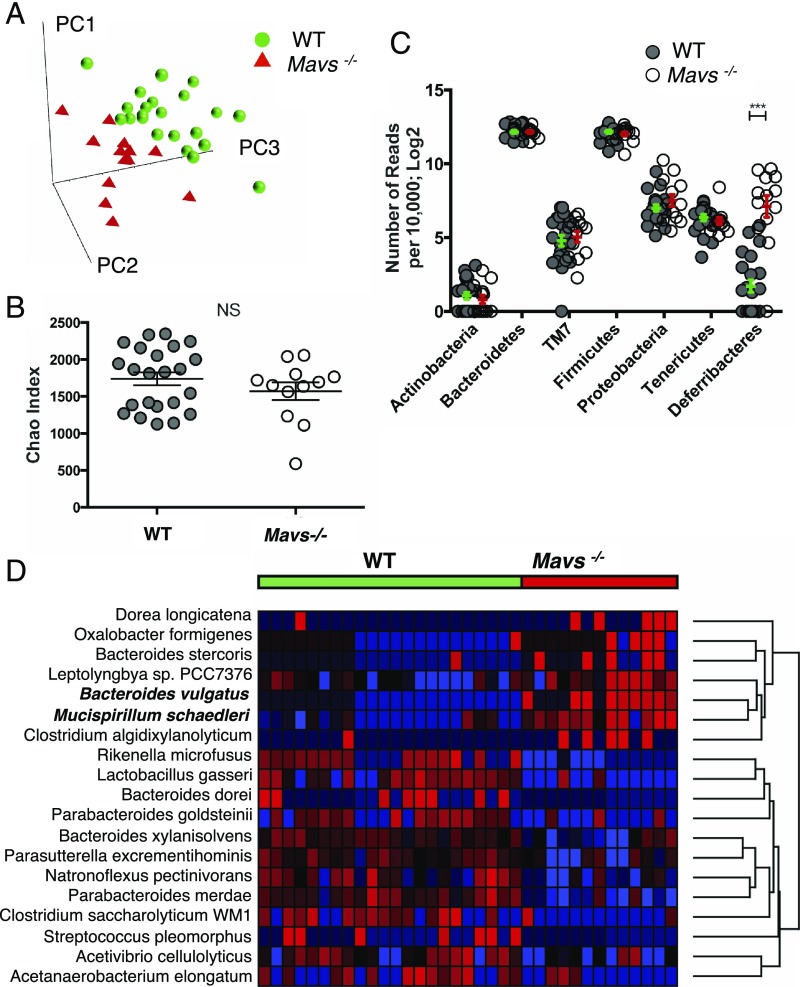

To identify specific gut bacterial communities that can be regulated by the RLR pathway, we performed two independent 454 high-throughput pyrosequencing comparisons of the variable bacterial 16S rRNA genes on feces from Mavs−/− and WT single-housed mice. Results showed microbial dysbiosis in Mavs−/− mice compared with either separated Mavs+/+ littermates (Mavs+/+litt) or WT animals, suggesting that MAVS genetic deficiency is responsible for dysbiosis. The same dysbiosis was observed in Mavs−/− mice bred in another animal facility, demonstrating that this effect is due to Mavs deficiency and is not inherent to the environment. As seen from multivariate principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1), Mavs−/− and WT mice exhibited substantial differences in overall gut microbial composition but no significant differences in the number of species by Chao’s index of species richness (Fig. 1B) or in measures of alpha diversity by inverse Simpson index. Further taxonomic analysis identified a 30-fold increase in the Deferribacteres phylum, driven by Mucispirillum schaedleri, in Mavs−/− compared with Mavs+/+ and WT mice (P < 10−6) (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the abundance of Bacteroides vulgatus was significantly increased in Mavs−/− animals (P < 10−9) (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Single-housed Mavs−/− and WT (B6J and Mavs+/+ litt) mice exhibit significant differences in gut microbial composition. (A) PCA of gut microbiota of Mavs−/− and WT mice. Species-level data were used to construct PCA plots. Data from two independent experiments are shown (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). PC1, PC2, PC3, principal components 1, 2, and 3, respectively. (B) Chao’s index of species richness in the feces samples of Mavs−/− and WT mice. Before the analysis sequences were clustered into OTUs with 97% similarity. Means ± SDs are shown. (C) Phylum-level analysis of the gut microbiota of Mavs−/− (open dots) and WT (gray dots) mice. Data are normalized to 10 000 reads per sample and are log2 transformed. The y axis represents the number of reads. Means ± SEMs are shown. (D) Heatmap visualization of the results of the species-level comparison of gut microbiota of Mavs−/− and WT mice. Significance was determined by Student’s t test and adjusted for multiple comparisons using the q-value method. Species with q < 0.05 were selected. Highly significant species (unadjusted P < 10−6) are labeled with bold font. ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant as determined by Student’s t test.

Increased Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity Observed in Mavs−/− Mice Is Inhibited by Antibiotics Treatment.

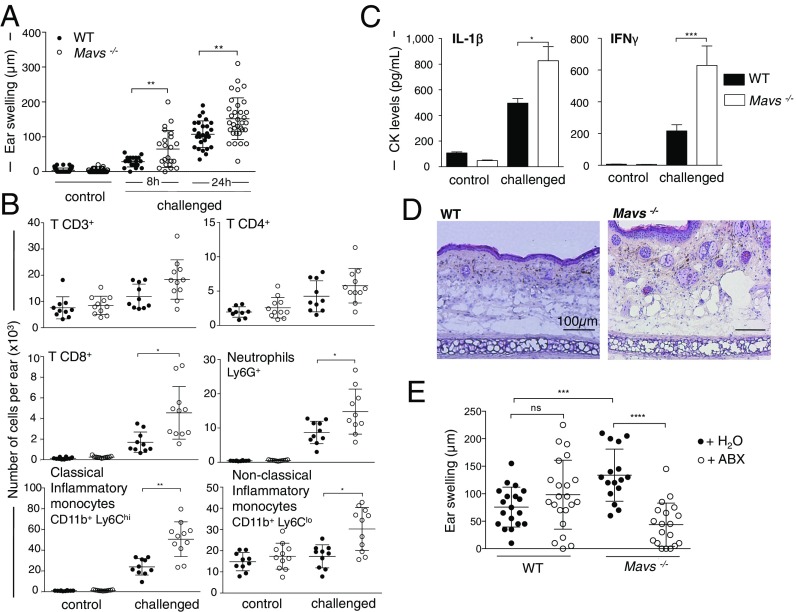

To assess potential links between RLR signaling, gut microbiota, and risk for skin allergy, we measured the delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response to the strong hapten 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) in mice deficient for the RLR adaptor MAVS. Single-housed Mavs−/− mice showed increased DTH severity demonstrated by a significant increase in ear swelling (Fig. 2A), while hapten-induced tissue irritation (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B) and DTH response kinetics (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C) were similar to those in WT mice. This enhanced DTH response was characterized by an increased immune cell infiltration (Fig. 2B) and cytokines characteristic of DTH reactions (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (14, 15). The higher infiltrate coincided with increased dermal edema and vascular enlargement as determined histological analysis on Mavs−/− ear sections (Fig. 2D). To define whether disease risk is related to impaired immune cells in Mavs−/− mice, we performed a multiparameter immunophenotyping of lymphoid organs and blood at steady state. Mavs−/− and WT mice showed a similar composition of main immune subsets in vivo (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) and equivalent T cell proliferation in vitro (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Disease risk in Mavs−/− mice is not due to increased hapten penetration, as no skin structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B) or permeability abnormalities (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C) were observed at steady state. Moreover, MAVS deficiency did not affect hapten uptake, skin dendritic cell (DC) migration, or T cell priming in the draining lymph node (dLN) during DTH response (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). To determine whether the gut microbiota contributes to the Mavs−/− DTH phenotype, Mavs−/− and WT animals were orally treated by broad-spectrum antibiotics (ABX), including ampicillin, neomycin, metronidazole, and vancomycin, shown to deeply impact gut but not skin microbiota (16). The inflammatory edema was strongly inhibited in ABX-treated Mavs−/− mice, whereas no impact was observed in WT-treated mice (Fig. 2E), demonstrating that the gut microbiota is a trigger for the higher severity of the DTH response in Mavs−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

DTH in single-housed Mavs−/− mice is characterized by increased edema that is inhibited by antibiotics treatment. (A) Ear swelling was measured 8 and 24 h after challenge (WT mice: n = 27; Mavs−/− mice: n = 33). Ear swellings measured at 8 and 24 h were pooled. The peak of the response can occur 24 or 48 h after challenge (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Results are mean values ± SDs (pool of three representative experiments among eight). (B) Analysis of adaptive and innate immune cell infiltration at the challenged site. Ears from WT (n = 10) and Mavs−/− (n = 11) mice were harvested at the peak of the response (24 h postchallenge), and immune cell recruitment was analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean values ± SDs of one representative experiment of two. (C) IL-1β and IFNγ cytokines were measured in ear supernatant 24 h postchallenge by ELISA. Data are mean ± SEMs of triplicate technical values (two experiments with n = 5). (D) Histology of Mavs−/− and WT ears harvested 24 h postchallenge. (E) WT (n = 22) and Mavs−/− (n = 19) mice were given ABX in the drinking water for 4 wk before and during the DTH experiment (control mice without ABX: WT n = 19, Mavs−/− n = 16). The antibiotic mixture was composed of 1 g/L each of ampicillin, neomycin sulfate, and metronidazole and 0.5 g/L of vancomycin hydrochloride. Ear swelling was measured 24 h postchallenge. Data are mean values ± SDs of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, and ns, not significant, as determined by nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) followed by the pairwise Dunn’s multiple comparison test (A) and Mann–Whitney U nonparametric test (B–E).

The Increased DTH Response Is Transmissible by the Gut Microbiota.

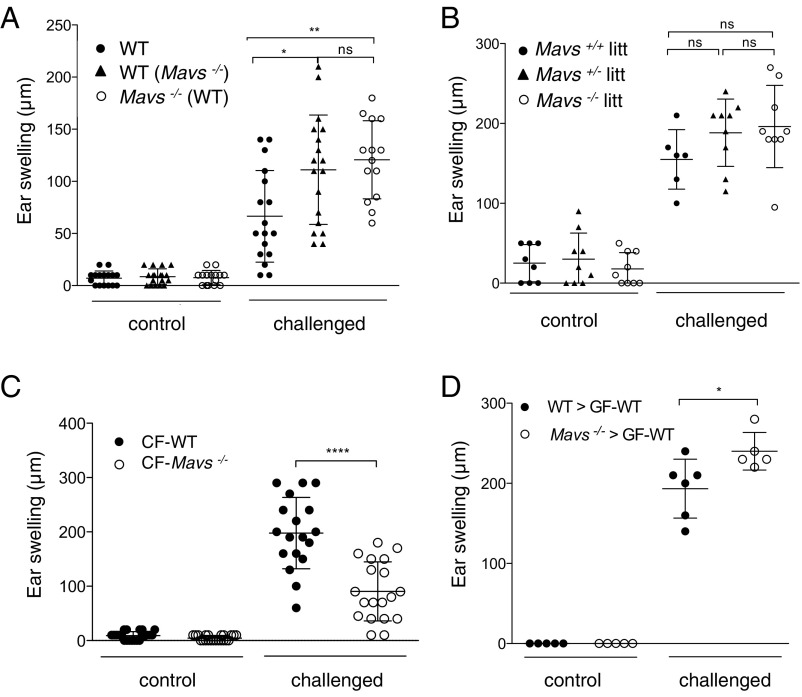

We next evaluated whether differences in the gut microbiota composition may be linked to disease risk in Mavs deficiency. WT and Mavs−/− mice were cohoused for 4 wk, and the DTH response was monitored. Cohoused WT and Mavs−/− mice exhibited the same increased edema as single-housed WT mice (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the Mavs−/− inflammatory phenotype is transmissible to WT animals. We confirmed that cohousing resulted in successful transfer of microbial species, as the PCA scatter plot showed an intermediate position of cohoused WT and Mavs−/− mice compared with single-housed animals (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), demonstrating that dysbiosis is transmissible by coprophagia. We next validated these results using littermates generated from in-house heterozygous crossing and housed together from birth to the day of the experiment. Results showed no difference in the ear swelling of Mavs−/−, Mavs+/−, and Mavs+/+ littermates cohoused from birth (Fig. 3B), suggesting maternal transmission from one generation to another by a dominant effect of MAVS deficiency on dysbiosis. To further establish that the Mavs−/− inflammatory phenotype is communicable from the mother to offspring, we performed cross-fostering experiments. WT mice cross-fostered (CF) at birth with in-house Mavs−/− mothers (CF-WT) developed a severe DTH response compared with Mavs−/− mice cross-fostered with in-house WT mothers (CF-Mavs−/−) (Fig. 3C). Finally, adult germ-free WT (GF-WT) mice were recolonized with a fresh supernatant from feces of either WT (WT → GF-WT) or Mavs−/− (Mavs−/− → GF-WT) mice. The DTH response was significantly greater in recipients replenished with the fecal microbiota from Mavs−/− animals than in WT → GF-WT mice (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Together, these results demonstrate that the Mavs−/− microbiota is a dominant proallergenic factor that is likely maternally transmissible from the earliest days of life onwards.

Fig. 3.

The increased DTH response in Mavs−/− mice is transmissible by the gut microbiota. (A) DTH experiments were conducted on single-housed WT mice (n = 17) and blindly on cohoused WT (n = 18) with Mavs−/− (n = 14) mice for 4 wk. Ear swelling was measured 24 h postchallenge. Results are mean values ± SDs (pool of two independent experiments). (B) Littermate mice (Mavs+/+ litt, n = 6; Mavs+/− litt, n = 9; Mavs−/− litt, n = 9) were generated from heterozygous crossing and kept in the same cage. DTH experiments were conducted blindly considering mouse genotype at 8 wk of age. Ear swelling was measured 24 h postchallenge. Data are mean values ± SDs of one representative experiment among three. (C) Newborn WT or Mavs−/− mice were cross-fostered with Mavs−/− mothers (CF-WT) or WT mothers (CF-Mavs−/−), respectively, within 24 h of birth. Ear swelling was measured 24 h postchallenge on mice at 6 wk of age. Results are mean values ± SDs of two independent experiments (CF-WT, n = 19; CF-Mavs−/−, n = 19). (D) Four weeks before DTH, GF-WT mice were reconstituted with fresh supernatant of fecal content from WT (WT → GF-WT; n = 6) and Mavs−/− (Mavs−/− → GF-WT; n = 5) mice. Ear swelling was measured at the peak of the response. Data are mean values ± SDs of one experiment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, ns, not significant as determined by nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) followed by the pairwise Dunn’s multiple comparison test (A and B) or Mann–Whitney U test (C and D).

Bacterial Translocation and Enhanced Inflammatory Cytokines in Secondary Lymphoid Organs Correlate with Increased DTH Response.

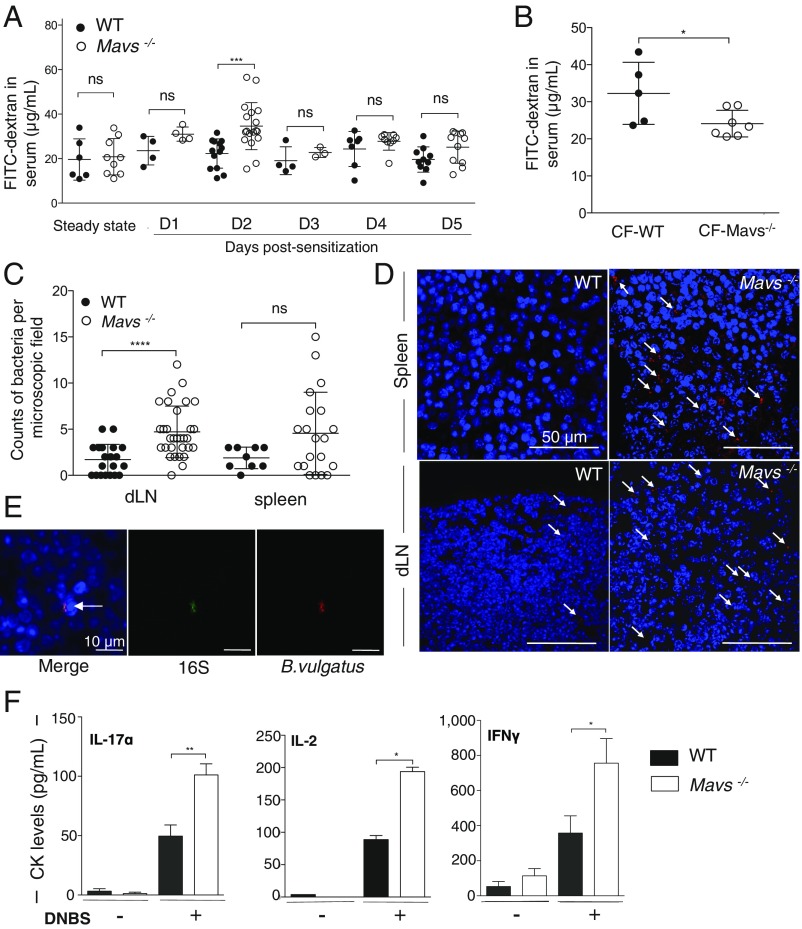

We next sought to understand how intestinal dysbiosis may influence the skin DTH response. Studies highlighted an increased intestinal permeability in patients with allergy such as atopic dermatitis (17–19). Intestinal histological analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S10) and immune subsets (lamina propria) of Mavs−/− mice revealed no defect at steady state. To evaluate whether Mavs−/−-increased DTH severity may be correlated to modifications in intestinal permeability during sensitization, mice were orally administered FITC-dextran. The FITC-dextran blood level was transiently increased 48 h after skin sensitization in Mavs−/− mice as compared with WT mice, whereas no difference was observed at steady state (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, CF-WT mice exhibited same increased intestinal permeability as CF-Mavs−/− mice, suggesting that dysbiotic microbiota transferred from Mavs−/− fostering animals is the key trigger for the intestinal defect during the DTH response (Fig. 4B). Increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation were correlated in mice (20), and bacterial translocation into secondary lymphoid organs was shown to be consecutive to intestinal barrier disruption (21). We thus investigate whether bacterial translocation in lymphoid organs could explain the increased DTH response of Mavs−/− mice. We used fluorescent 16S rRNA-targeted probes to detect translocating bacteria and recovered an increased number of bacteria in dLNs and spleens from Mavs-deficient mice (Fig. 4 C and D). Notably, we identified B. vulgatus in dLNs of Mavs−/− mice (Fig. 4E). Secretion by hapten-specific CD8+ T cells of Th1 (IFNγ, IL-2) and Th17 (IL-17) cytokines in skin dLNs after sensitization was markedly increased in Mavs−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4F), suggesting that translocating bacteria may provide costimulatory signals enhancing the immune response during DTH.

Fig. 4.

Mavs−/− gut dysbiosis results in bacterial translocation and enhanced inflammatory cytokines in secondary lymphoid organs. (A) Intestinal permeability assays measuring 4-kDa FITC-dextran accumulation at steady state and during DTH sensitization. Data are mean values ± SDs of six independent experiments; n = 13 WT and n = 18 Mavs−/− mice at day 2. (B) Intestinal permeability assay measuring FITC-dextran accumulation 2 d after sensitization on CF animals. Data are mean values ± SDs of one experiment with n = 5 CF-WT and n = 7 CF-Mavs−/− mice. (C and D) Bacteria quantification in secondary lymphoid organs by FISH staining. (C) Data are mean ± SDs of bacterial counts in each field with 10 acquisitions per organ (dLNs: n = 3 Mavs−/− mice and n = 2 WT mice; spleen: n = 2 Mavs−/− mice and n = 1 WT mice). (D) Sections of spleens and dLNs from WT and Mavs−/− mice harvested 5 d postsensitization were stained with the pan-bacterial probe Eub338 (red). Bacteria were counted in 10 microscopic fields (135 × 135 μm) randomly selected across organ sections. (E) Confocal images of Mavs−/− dLNs harvested 5 d postsensitization and stained with16S and specific B. vulgatus probes. (F) dLNs were collected 5 d postsensitization, and cells were cultured for 20 h with a soluble analog of DNFB, dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (DNBS). Cytokine measurement was performed in supernatants by ELISA. Data are mean ± SEM (technical triplicates, two experiments with five or six mice). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns, nonsignificant as determined by Mann–Whitney U test (A–C and F).

Discussion/Conclusion

Collectively, our results indicate that intestinal dysbiosis increases skin allergy severity. We found that MAVS deficiency leads to changes in the gut bacterial composition that exert their effect through an increased intestinal permeability during DTH sensitization. The ensuing bacterial translocation within lymphoid organs leads to increased cytokine production and DTH severity. This paradigm revealed an unexpected protective role for a cytosolic surveillance system involved in viral RNA detection in the development of skin allergy resulting from specific changes in the composition of enteric bacterial residents. Our results are complementary to the role of MAVS in monitoring intestinal commensal bacteria and maintaining intestinal tissue homeostasis described by Li and colleagues (13). Moreover, the RIG-I/MAVS pathway activation and subsequent IFN-I signaling were recently shown to maintain gut epithelial barrier integrity (22). RIG-I was described as being constitutively expressed at the apical surface of intestinal human biopsies (23). These observations, associated with a “leaky gut” phenotype described in allergic atopic patients (17–19), suggest that intestinal permeability and gut microbiota composition may impact skin allergy in humans. Manipulation of the gut microbiota, shown to enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade in anticancer therapy (24–26), may represent therapeutics for human allergic skin diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Mavs-deficient (Mavstm1Tsc/tm1Tsc) mice were kindly provided by J. Tschopp, Biochemistry Department, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. These mice were bred as homozygotes in our animal facility [Plateau de Biologie Expérimentale de la Souris (PBES), Structure Fédérative de Recherche Biosciences] under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mavs-deficient mice were generated on a pure B6J background (27). We confirmed the pure B6J background by SNP analysis as described by Simon et al. (28). All control mice were C57BL/6J. Animal experimental procedures were conducted using 6- to 12-wk-old mice in accordance with the animal care guidelines of the European Union and French laws and were validated by the local institutional review board (Comité d'Evaluations Commun au Centre Léon Bérard, à l'Animalerie Transit de l'ENS, au PBES et au Laboratoire P4).

Analysis of Microbiota Using 16S rRNA Sequencing.

Genomic DNA was isolated from fecal pellets using the QIAamp DNA Stool kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 16S rRNA gene analysis was done by sequencing the V1–V3 region. A fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using 27F 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and 534R 5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-3′ primers with barcodes and sequencing primers. PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 56 °C, and 5 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified (AMPure; Beckman Coulter), quantified (Bioanalyzer; Agilent), and pooled in equimolar concentrations. Emulsion PCRs were made using the Roche 454 emPCR Lib-A LOVE kit (Roche). Sequencing was done using the Roche 454 FLX Titanium protocol. Sequence processing and analysis were performed using Mothur v1.22.0 software. Briefly, low-quality sequences and PCR chimeras were removed using the UCHIME algorithm and the Mothur plugin. Sequences were aligned to a custom-built reference dataset of bacterial 16S rRNA sequences. For operational taxonomic unit (OTU) analysis, sequences were aligned to the SILVA reference dataset, clustered, and binned into the same OTUs if more than 97% similarity was found. Bacterial diversity indexes (Chao and the Inverse Simpson Index) were also calculated using Mothur software. Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or two-way ANOVA (Partek 6.0 software). The P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the q-value method. The differences between groups were visualized using a PCA plot. Supervised hierarchal clustering was used to make a heatmap.

Mouse Ear-Swelling Test.

The mouse ear-swelling test procedure was used to measure DTH responses. Female mice were sensitized epicutaneously on the shaved abdomen with 25 μL 0.5% DNFB (Sigma) diluted in acetone-olive oil (4:1, vol/vol) on day 0. On day 5, DNFB-sensitized and unsensitized control mice were challenged with 5 μL of 0.13% DNFB on both sides of one ear. The other ear was painted with vehicle alone. The increase in ear swelling was measured at different time points after challenge using a spring-loaded micrometer (Blet). Nonresponding animals were excluded from analysis. Due to the interindividual variability of our experimental model, we used 4–12 mice per experiment to ensure adequate statistical power. No method of randomization was used. No blinding to the group allocation during experiments was used except for cohousing and littermates experiments.

Cohousing, Cross-Fostering, Fecal Transplantation, and Antibiotic Treatment.

For cohousing experiments, WT and Mavs−/− mice were transferred at a 50/50 ratio into an isolator cage for 4 wk on the same diet before the DTH experiment. For littermates experiments, Mavs+/+, Mavs+/−, and Mavs−/− mice were generated from heterozygous crossing and were kept in the same cage. DTH experiments were conducted blindly considering genotype at 6 wk of age. For cross-fostering experiments, newborn mice were exchanged between WT and Mavs−/− mothers within 24 h of birth. Mice were weaned between postnatal days 21–28. For the fecal transplantation experiment, GF-WT mice were generated at the Transgenesis and Archiving of Animal Models-CNRS facility and were transferred into autoclaved sterile microisolator cages before gavage with 200 μL of fresh supernatant from feces of WT or Mavs−/− mice. The DTH experiment was performed 4 wk after fecal transplantation. For ablation of the intestinal bacteria, an antibiotic mixture of 1 g/L each of ampicillin (sodium salt; Sigma), neomycin sulfate (Sigma),and metronidazole (Sigma) and 0.5 g/L of vancomycin hydrochloride (Mylan) was added to the drinking water for 4 wk and was changed twice a week. Antibiotics activity was gauged by Gram staining of cecal material and quantification of 16S rRNA gene copies per gram of feces that demonstrated depletion of bacteria.

In Vivo Assay of Intestinal Permeability.

An in vivo assay of barrier function was performed using FITC-labeled dextran under steady-state conditions and during the sensitization phase of DTH (2 and 5 d postsensitization). Briefly, B6J WT and Mavs−/− mice were deprived of food and water for 4 h. Then mice were gavaged with the paracellular permeability tracer FITC-labeled dextran 4 kDa (0.6 mg/g of body weight; Sigma-Aldrich). Blood was collected retroorbitally after 3 h, and the fluorescence intensity of each sample was measured (excitation: 492 nm; emission: 520 nm; TECAN Infinite 200 machine) in serum. FITC-dextran concentrations were determined from a standard curve generated by serial dilutions of FITC-dextran.

FISH.

Spleens and dLNs harvested 5 d after DNFB sensitization were embedded in paraffin and cut to a thickness of 5 μm using a Shandon Finesse ME+ microtome (Thermo Electron). Paraffin sections were rehydrated in 100% ethanol, 90% ethanol, 70% ethanol, and water for 5 min each and with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After two washes with PBS, slides were covered with a solution of lysozyme at 10 mg/mL in PBS for 20 min at 50 °C and were washed twice with PBS. After 30 min of incubation in hybridization buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 0.9 M NaCl, 0.01% SDS, 30% formamide], slides were incubated overnight at 50 °C in hybridization buffer containing 20 nM of the fluorescent probes. After washing twice in 1× SSC (0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), slides were covered for 10 s with DAPI (0.125 g/mL in PBS), washed in PBS, and mounted in Fluoromount (Invitrogen). The 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes used were Eub338 5′-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′ and non-Eub338 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGC-3′. The probes were covalently linked with Alexa 555 and FITC, respectively at their 5′ ends. The B. vulgatus probe used was Bvul-R 5′-GGCTTCTTACTTTCTCTCTTCCG-3′ covalently linked with Alexa 647 at the 5′ end. Slides were examined with a Zeiss LSM 780 NLO confocal microscope. To evaluate the number of bacteria in each organ, we enumerated the number of red spots in 10 images per organ, taken randomly.

Histology.

Ears from B6J and Mavs-deficient mice were collected 24 h after DNFB challenge, fixed, and stained with H&E (Novotec). Slides were observed with a Zeiss Axio Imager microscope and analyzed using ImageJ software (Fig. 2D). Hairs were plucked from the mouse back skin and examined with a stereomicroscope. In the mouse coat, four hair types can be distinguished. Awl and guard hairs are straight, and the latter are longer. Auchene and zigzag hairs have one or multiple bends, respectively. Based on these morphological hallmarks, the presence of the different hair types was determined. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. The back skin was shaved and isolated by dissection. Whole skin samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h and processed for paraffin embedding and sectioning. Sections were stained with H&E, and general morphology was investigated with a Zeiss Axioskop2 microscope (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Skin Permeability Measurement.

Female mice were acclimatized for 30 min, and measurements were performed at a room temperature of 24.2 °C and 54.6% relative humidity. Basal transepidermal water loss (TEWL) was measured using a Tewameter TM 300 measuring device (Courage-Khazaka Electronic GmbH) on shaved skin from different areas of the mouse back and belly according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Enzyme-Linked Immunospot Assay.

The enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay was developed to estimate the number of antigen-specific IFNγ-producing cells. Axillary and inguinal dLNs were collected 5 d postsensitization. Isolated cells were plated (0.8 × 106, 0.4 × 106, or 0.2 × 106 cells per well) in Multiscreen 96-well filter plates (Millipore) and were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 20 h with or without DNBS (4 mM). The ELISPOT IFNγ Kit pair (BD Biosciences) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase conjugate was obtained from eBioscience, and AEC substrate was obtained from BD Biosciences. Spots were counted with CTL S6 UV and were analyzed with Immunocapture 5.0 Analyzer Professional DC software.

Tracking of Skin DC Migration.

WT and MAVS-deficient mice were painted on the dorsal side of each ear with 10 μL of TRITC (Molecular Probes) diluted at 0.1 mg/mL in 10% DMSO (Sigma) and 90% acetone-dibutil phthalate (1:1, vol/vol). Forty-eight hours later, CD11c+ cells from cervical dLNs were collected and were analyzed by FACS for TRITC, I-A/I-E, CD207, and CD103 expression. Labeled antibodies I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), CD207 (929F3), CD103 (2-E7), and CD11c (N418) were obtained from eBioscience.

Immune System Phenotyping in Blood and Lymphoid Organs.

Stainings for flow cytometry were also performed on freshly isolated splenocytes, cells of the dLNs, and blood with the collaboration of the AniRA Phenotyping Facility. Labeled antibodies B220 (RA3-6B2), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (53-6.7), TCRγδ (GL3), NK1.1 (PK136), FoxP3 (FJK-16s), Siglec-H (eBio440c), CD205 (NLDC-145), CD11c (N418), CD45 (30-F11), CD3 (2c11), CD25 (PC61), Ly6G (IA8), CD11b (M1/70), CD115 (AFS98), and Ly6c (AL21) were obtained from eBioscience, BD Biosciences, and BioLegend.

Flow Cytometry Analysis on Ears.

Flow-cytometric experiments were conducted on entire ear cells harvested at 8 h and 24 h postchallenge. Mouse ear halves were split and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min with collagenase (Sigma) and DNase I (Roche) in RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 25-mM Hepes (Gibco). Cells were next filtrated through a 100-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon), stained with labeled antibodies [CD45 (30-F11), CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (CT-CD4), CD8 (53-6.7), Ly6G (IA8), CD11b (M1/70), and Ly6C (AL21)], and analyzed by FACS on a BD LSR II flow cytometer. Labeled antibodies were obtained from eBioscience or BD Biosciences. Data were analyzed using FlowJo 887 software (Tree Star). Flow-count fluorospheres (Beckman Coulter) were used to determine absolute counts.

ELISA and Multiplex Assay.

Challenged mouse ear halves were split and incubated at 37 °C for 30 h. DNBS-restimulated cells from dLNs (1 × 106 cells) were incubated at 37 °C for 20 or 48 h. Cytokine concentrations in culture supernatants were measured by specific ELISAs according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Optical density was read with a TECAN Infinite 200 machine using i-control software. ELISA kits were obtained from R&D Systems (IFNγ, IL-1β) or BioLegend (IL-17α). Production of IL-2 by CD8+ T cells from DNBS-restimulated dLNs was analyzed in culture supernatant using the Bio-Plex Pro Mouse cytokines 23-plex Assay (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence analysis was performed using the Bio-Plex MAGPIX Multiplex Reader, and results were analyzed using Bio-Plex Manager software.

Gut Paraffin Sections and Immunohistochemistry.

Mice were killed at 6 wk of age, the intestine was quickly removed, and samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before being embedded in paraffin and cut in 5-μm-thick sections for histological (H&E staining) and immunohistochemical experiments. Briefly, the sections were deparaffinized in methylcyclohexane, hydrated in ethanol, and washed with PBS. The slides were subsequently subjected to antigen retrieval using microwave heating in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with blocking buffer (10% normal goat serum, 1% BSA, and 0.02% Triton X-100 in PBS). The slides were incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-Ki67, 1:200; rabbit anti-Lysozyme, 1:1,000) (both from Abcam) overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with fluorescent secondary antibodies (donkey anti-rabbit; 1:500; Jackson Laboratories). All nuclei were stained with Hoechst (Sigma). Slide observation and cell counting were done using a Zeiss Z1 Imager. Images were acquired using a Leica SP5X confocal microscope with an HC PL APO 20× ON 0.7 oil immersion objective.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test, Mann–Whitney U nonparametric test, or nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) followed by a pairwise Dunn’s multiple comparison test to analyze the significance among different groups using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Error bars represent SDs or SEMs of the mean.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Tschopp’s laboratory for Cardif (MAVS-deficient) mice; Martine Tomkowiak, Julien Mafille, and Barbara Gilbert for expert technical assistance; Anca Hennino for confocal images; Christophe Arpin and Mohamad Sobh for statistical data analysis; Bertrand Dubois, Marc Vocanson, and Jean-François Nicolas for helpful discussions on the DTH model; Thierry Walzer, Laurent Genestier, Bertrand Dubois, and Gérard Eberl for critical reading of the manuscript; Bariza Blanquier for help with qPCR analysis (genetic analysis); Thibault Andrieu and Sébastien Dussurgey (AniRA-Cytometry); Olga Azocar and Christophe Chamot from the Plateau Technique Imagerie/Microcopie; and the staff of AniRA-PBES, especially Jean-Louis Thoumas and Céline Angleraux. We acknowledge the contributions of the Structure Fédérative de Recherche BioSciences Gerland-Lyon Sud (UMS3444/US8-Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon, Universite Claude Bernard de Lyon CNRS, INSERM) facilities, especially AniRA ImmOS. This work was supported by Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université de Lyon I, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Association “ARCHE,” and Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grant ANR-11-RPIB-0019-03 (to J.M.), a grant from the Département du Rhône-Fonds Européen de Développement Régional (PLATINE) (J.M.), and European Commission Grant LSHG-CT-2006-037188, The European Mouse Disease Clinic (to J.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1722372115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lee YK, Mazmanian SK. Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Science. 2010;330:1768–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1195568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanov II, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abt MC, et al. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2012;37:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ichinohe T, et al. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAleer JP, Kolls JK. Maintaining poise: Commensal microbiota calibrate interferon responses. Immunity. 2012;37:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrahamsson TR, et al. Probiotics in prevention of IgE-associated eczema: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1174–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Candela M, et al. Unbalance of intestinal microbiota in atopic children. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penders J, Stobberingh EE, van den Brandt PA, Thijs C. The role of the intestinal microbiota in the development of atopic disorders. Allergy. 2007;62:1223–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strange A, et al. Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium; The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 A genome-wide association study identifies new psoriasis susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA-C and ERAP1. Nat Genet. 2010;42:985–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vijay-Kumar M, et al. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3909–3921. doi: 10.1172/JCI33084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XD, et al. Mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) monitors commensal bacteria and induces an immune response that prevents experimental colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17390–17395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107114108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kehren J, et al. Cytotoxicity is mandatory for CD8(+) T cell-mediated contact hypersensitivity. J Exp Med. 1999;189:779–786. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kish DD, Gorbachev AV, Fairchild RL. IL-1 receptor signaling is required at multiple stages of sensitization and elicitation of the contact hypersensitivity response. J Immunol. 2012;188:1761–1771. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naik S, et al. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science. 2012;337:1115–1119. doi: 10.1126/science.1225152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caffarelli C, Cavagni G, Menzies IS, Bertolini P, Atherton DJ. Elimination diet and intestinal permeability in atopic eczema: A preliminary study. Clin Exp Allergy. 1993;23:28–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1993.tb02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pike MG, Heddle RJ, Boulton P, Turner MW, Atherton DJ. Increased intestinal permeability in atopic eczema. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;86:101–104. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12284035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ukabam SO, Mann RJ, Cooper BT. Small intestinal permeability to sugars in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:649–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrier L, et al. Stress-induced disruption of colonic epithelial barrier: Role of interferon-gamma and myosin light chain kinase in mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:795–804. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viaud S, et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science. 2013;342:971–976. doi: 10.1126/science.1240537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer JC, et al. RIG-I/MAVS and STING signaling promote gut integrity during irradiation- and immune-mediated tissue injury. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaag2513. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawaguchi S, et al. Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I is constitutively expressed and involved in IFN-gamma-stimulated CXCL9-11 production in intestinal epithelial cells. Immunol Lett. 2009;123:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Routy B, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359:91–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gopalakrishnan V, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359:97–103. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matson V, et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359:104–108. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michallet MC, et al. TRADD protein is an essential component of the RIG-like helicase antiviral pathway. Immunity. 2008;28:651–661. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon MM, et al. A comparative phenotypic and genomic analysis of C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mouse strains. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R82. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-7-r82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.