Summary

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a ubiquitous, persistent beta herpesvirus. CMV infection contributes to the accumulation of functional antigen‐specific CD8+ T‐cell pools with an effector‐memory phenotype and enrichment of these immune cells in peripheral organs. We review here this ‘memory T‐cell inflation’ phenomenon and associated factors including age and sex. ‘Collateral damage’ due to CMV‐directed immune reactivity may occur in later stages of life – arising from CMV‐specific immune responses that were beneficial in earlier life. CMV may be considered an age‐dependent immunomodulator and a double‐edged sword in editing anti‐tumour immune responses. Emerging evidence suggests that CMV is highly prevalent in patients with a variety of cancers, particularly glioblastoma. A better understanding of CMV‐associated immune responses and its implications for immune senescence, especially in patients with cancer, may aid in the design of more clinically relevant and tailored, personalized treatment regimens. ‘Memory T‐cell inflation’ could be applied in vaccine development strategies to enrich for immune reactivity where long‐term immunological memory is needed, e.g. in long‐term immune memory formation directed against transformed cells.

Keywords: age‐dependent immunomodulator, anti‐tumour immunity, cytomegalovirus, immune‐fitness, memory T‐cell inflation

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a ubiquitous virus found in > 50% of the world's population,1 commonly characterized by latency and lifelong persistence after primary infection in the immunocompetent host.2 Using a broad‐spectrum of strategies to facilitate its persistence, CMV can survive in the host despite robust innate and adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, CMV can cause life‐threatening infections in individuals with a suppressed immune system or immunodeficiency disorders. CMV remains a challenging obstacle in transplant recipients.3 CMV‐specific cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte immune responses require reconstitution to confer long‐term protection against CMV reactivation and disease after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT),4, 5 although the use of prophylactic and pre‐emptive antiviral chemotherapy strategies has significantly reduced the morbidity and mortality of CMV infection in these individuals. Adoptive transfer of donor‐derived CMV‐specific immune cells to patients with CMV infection and disease has been established,6 whereas a variety of clinical methods for CMV‐specific immunotherapy have been developed to offer novel biotherapeutic options to patients with uncontrolled viraemia.

An interesting phenomenon concerning CMV infection is that the frequencies of CD8+ T cells increase during latency, which has been dubbed ‘memory inflation’,7 driven by low‐level persistence of CMV DNA.8, 9 In contrast to other virus‐specific T cells, human CMV‐specific immune responses impact greatly on the quality and quantity of the memory T‐cell compartment.7, 10 An average of 10% and 9% of blood CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively, in healthy individuals are CMV‐specific.7 In a recent and elegant systems‐level analysis of the immune system of healthy twins, human CMV infection was shown to have a significant, non‐heritable impact on 58% of various immunological parameters (notably including effector CD8+ and γδ T cells) modulating the overall immune profile of healthy individuals.11 This suggests that repeated environmental pressure, like CMV infection, causes shifts in immune‐cell frequencies and other parameters and, with time, outweighs most heritable factors, which impose a profound impact on immunological homeostasis. It is, therefore, plausible that CMV‐directed immune responses also shape anti‐tumour immune responses.

Features of CMV‐specific memory T‐cell inflation

Memory T‐cell inflation of CMV infection is characterized by the accumulation and maintenance of a vast number of effector‐memory T cells, identified in humans and mice.12, 13, 14 The effector‐like phenotype of the inflationary memory CD8+ T cells is characterized as CD27low, CD28−, CD62L−, CD127−, KLRG1+, PD‐1−, IL‐2+/−, whereas in the long‐term central‐memory pools, the surface marker profile is characterized as CD27+, CD28+, CD62L+, CD127+, KLRG1−, PD‐1+ and IL‐2+ T cells – from which effector‐memory T cells can also be re‐generated.6, 15, 16, 17 In contrast to other exhausted T cells in the presence of actively replicating viruses, CMV‐specific inflationary memory T cells are still functional and able to migrate into virtually all tissues.7, 18, 19, 20 This crucial characteristic lays the foundation for CMV‐based vaccination efforts or CMV‐based T‐cell therapy to confer anti‐tumour effects in different organs.21, 22 ‘Inflationary CD8+ T cells’ express also the fractalkine (chemokine) receptor CX3CR1, which is associated with tissue homing – and with reduced T‐cell proliferative capacity. However, there is also a distinct subset of CMV‐specific T cells that express intermediate levels of CX3CR1, these immune cells have the capacity to proliferate and mediate immune effector functions, important components to provide local immune‐surveillance and tissue protection.23 Inflationary T cells are often restricted in T‐cell receptor (TCR) usage, enriched for TCRs targeting immunodominant CMV antigens.24 Pera et al.25 recently extended previous observations of the effect of CMV on CD8+ T‐cell functionality as well as CD4+ T cells, showing CD57 as a marker for polyfunctional T cells after CMV infection. CD4+ T cells co‐expressing CD57 and CD154, which are exclusively present in CMV‐positive individuals, exhibit the greatest degree of polyfunctionality in the CD4+ subset, whereas CD4+ CD27+ CD28− T cells associate with ‘reduced’ polyfunctionality. Interestingly, inflationary CD4+ T cells are prominent compared to CD8+ T cells, at least in the murine CMV (MCMV) infection model.26, 27 It is still unknown what triggers the selection of the inflationary epitopes, although it has been demonstrated that CMV epitopes driving inflationary CMV‐reactive immune responses are independent of initial immunodominance and viral gene expression patterns.6, 7 It is also known that CD4+ T‐cell help, CD27, OX40 and 4‐1BB expression, as well as interleukin‐2 (IL‐2) production, are required for inflationary CD8+ T‐cell responses.28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Up to now, the mechanism(s) by which CMV is able to persist – and also is able to persistently stimulate T cells, without being eliminated, are still not resolved. The general view is that a low‐grade ‘smouldering’ infection induced by CMV can be rapidly eradicated. This would result in CMV no longer being detectable – whereas the latent anti‐CMV T‐cell pool is being replenished, leaving the immune system in a highly activated state. In the MCMV model, the infection‐driven inflated T‐cell memory responses seem to be dependent on continuous antigen stimulation for maintenance. Such ‘inflated’ T‐cell memory diminishes after the immune‐competent host is treated with prolonged antiviral therapy or if immune cells are transferred to CMV‐naive hosts, where antigen stimulation would not occur.15, 33 The dose of the viral inoculum also impacts memory T‐cell inflation, reflected by the relationship between memory inflation and the antigen load encountered by T cells. After low‐dose inoculation with MCMV, the accumulation of inflationary memory T cells was severely affected and correlated with reduced reservoirs of latent virus in non‐haematopoietic cells and dampened antigen‐driven T‐cell proliferation.34 Trgovcich et al.35 reported that low‐titre CMV infections induce ‘partial’ memory inflation of MCMV‐specific CD8+ T cells, whereas high‐titre primary infections can produce memory inflation. The same study showed that re‐infection with different viral strains could boost partial memory inflation,35 as CMV re‐infection/co‐infection may frequently occur in immunocompetent hosts with ~ 10% re‐infection cases per year (data from a cohort of female patients).36 As the duration of CMV infection in humans is usually not known, measuring the development of T‐cell responses at the time of infection is limited to the clinical context of HSCT or organ transplantation.37

Exhaustion and senescence

Because changes are observed rapidly after primary infection in transplant patients and infants,38, 39 it is highly likely that CMV drives the accumulation of late‐stage, memory CD8+ T cells. However, recent results suggest that a single strong reactivation stimulus does not favour memory inflation,35 an observation that warrants further investigation. It is biologically and clinically relevant to differentiate between ‘exhaustion’ and ‘senescence’ of T cells. Senescent T cells may not be easily rescued in contrast to their exhausted counterparts (reviewed in Xu and Larbi40). Senescence markers on T cells comprise CD57 and KLRG‐1,41 while the cells exhibit a pro‐inflammatory profile and usually reside in the terminally differentiated T‐cell compartment. In contrast, exhausted T cells express a different marker profile: programmed cell‐death protein 1 (PD‐1), cytotoxic T lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4 (CTLA‐4), T‐cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM‐3) or lymphocyte‐activation gene 3 (LAG‐3). They also display a reduced capacity to proliferate or to produce cytokines and are usually found in the effector and/or effector‐memory populations.42 These immune marker profiles may apply to CD3+ CD8+ TCR‐αβ T cells as well as TCR‐γδ (particularly Vδ2+) T cells.43 CMV has been shown to drive antigen‐specific T cells into immune senescence, which also extends to TCR‐γδ cells in relation to immunological ageing.43, 44 Such CMV‐reactive T cells, which produce tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), may contribute to a ‘low‐grade chronic inflammatory environment’ in the elderly that contributes to age‐related diseases.43

Homeostasis of and selection pressure on CMV‐directed T cells

In addition to ‘occupying’ T‐cell space and competition for T‐cell growth factors, i.e. IL‐2, IL‐7, IL‐15, the antigen processing and presentation machinery (APM) plays a major role in memory T‐cell homeostasis. The APM in professional antigen‐presenting cells leads to generation of a broad array of target peptide epitopes compared to the APM in somatic cells. Hence, the nature of the antigen‐presenting cell itself and the position of the nominal T‐cell epitope within the target molecule drive strong and long‐lasting cellular immune responses.43, 45 Non‐haematopoietic cells, which produce IL‐15, support inflationary CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells, suggesting a particular cytokine‐enriched niche for the survival and maintenance of these effector cells.46 Furthermore, work performed in mice using MCMV infection (which most closely mimics the immunodynamics of human CMV infection) showed that non‐haematopoietic cells in lymph nodes present antigen to central‐memory CD8+ T cells to drive inflationary responses.8 These findings warrant extensive screening of human tissue samples for CMV‐reactive central‐memory T cells which occupy long‐term memory compartments and possibly impact on the ‘milieu interne’ of local immune responses to transformed cells.

Another critical factor which influences the expansion of CMV‐reactive T cells is the available TCR repertoire capable of reacting to CMV epitopes. Overall clonal TCR diversity in an individual, if estimated to be 1015, may in fact reflect lower numbers because humans have approximately 1011 precursor (‘naive’) T cells available.47 This implies that several peptides are recognized by the same TCR (cross‐reactivity), and conversely, that a single peptide can be recognized by several TCRs (promiscuity). More recent work using unique molecular identifier‐labelled high‐throughput sequencing and single T‐cell analysis of an HLA‐A2‐restricted CMVpp65 target (amino acids 495–503) showed that the diversity of TCRs recognizing a single epitope is far greater than expected.43, 48 Several thousand TCR species recognized the same epitope, whereas TCRs against this single epitope represented about 3‐4% of the entire peripheral T‐cell pool. This study underlined that most T‐cell analyses performed using T cells in peripheral circulation, which represent only about 2% of the entire lymphocyte pool [the remaining T cells (c. 98% of total) reside in organs and tissues], do not necessarily encompass the entire repertoire of CMV‐specific TCRs. For instance, resident memory T cells in the lungs account for a large memory T‐cell pool (up to 5 × 1010 cells). ‘Tissue‐seeding’ of T cells appears to occur early in childhood and shapes the TCR repertoire by exposure to environmental stimuli as well as respiratory infections.47 Nevertheless, T cells may also be able to survive for decades;49 this cellular repertoire may be shaped by epigenetic imprinting (for review see Goronzy and Weyand50) in addition to tissue homing and TCR affinity for the nominal MHC class I/peptide epitope.51

Detailed investigations using human clinical samples showed that CMV plays an ‘instructing role’ in modulating homeostasis of circulating T cells and on other cell populations of myeloid and lymphoid origin. One of the most prominent effects of human CMV infection is the modulation of the absolute numbers of peripheral blood T cells. The circulating T‐cell pool is characterized by the expansion of memory T cells after recovery from primary infection; significant differences persist between seronegative and seropositive subjects.9, 52, 53 Most memory T cells, particularly CD8+ T cells, monocytes as well as leucocytes, are increased in seropositive healthy adults after an interval of 5 years, whereas naive/precursor CD8+ T cells are decreased.54 CMV‐specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells can also dominate the memory compartment of seropositive humans.7 Furthermore, the effector‐memory T‐cell pool of CMV‐specific T cells varies among individuals and seems to correlate with the memory CD8+ T‐cell pool size.55, 56 The opposing trends between two groups of individuals (CMV serostatus +/−) showed that the change of the CD4/CD8 ratio over time may be influenced by CMV infection; the former was significantly reduced in CMV‐seropositive individuals but it was increased in seronegative individuals.54

In contrast, most inflationary cells in MCMV‐infected mice fail to sustain their numbers through homeostatic or antigen‐driven division and are programmed to perish, even in the presence of chronic CMV infection. MCMV‐specific T cells do not undergo homeostatic division and have a relatively poor proliferative potential.8, 57, 58 CMV‐specific, inflationary, terminally differentiated effector T cells have a half‐life of about 45–60 days.15, 20 This indicates that although CMV‐specific T cells can control the infection, they are relatively poor at maintaining their own survival. However, the inflationary T cells are continuously replenished by nascent virus‐specific effector cells that are recruited from a pool of memory cells, which form early after infection.15

CMV‐specific memory T‐cell inflation plays a dual role in immune signatures

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that CMV‐specific memory inflation is associated with immune senescence. CMV‐specific memory inflation has been postulated to promote the immune risk profile, which is predictive of decreased immune function and overall poor patient survival.59 CMV may reactivate more frequently in older people, requiring ever more immune resources to keep CMV under control and eventually reducing the host's ability to fight pathogens.60, 61 Low‐avidity CD45RA+ CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells in blood from older adults have been observed to be numerically higher, raising the possibility that accumulation of these CMV‐directed immune cells, in particular, may skew the TCR repertoire in CMV‐infected individuals during ageing.62 CMV‐induced effector‐memory T cells have been shown to overcrowd T‐cell populations that are directed against non‐CMV targets,63, 64 so impairing immune responses directed against infections and/or vaccinations especially in the elderly.10, 65, 66 Like humans, MCMV‐specific T cells in mice accumulate at the cost of CD8 T‐cell functionality against other viral pathogens, which indicates that these T cells may compete with reactivity to novel antigens.67, 68 Although both ageing and CMV infection have a profound effect on immune response patterns in humans, broad CMV‐specific reactivity profiles have also been described in younger populations.69 This suggests that CMV‐driven immune inflation is not a direct result of ageing of the host but rather that the CMV‐specific immune response itself may account for changes to the immune system that are related to ‘ageing’. Another noteworthy observation is that inflationary CD8+ T cells in individuals who are CMV‐seropositive also have higher expression of T helper type 1‐associated markers such as T‐bet and eomesodermin (or EOMES) compared to CD4+ T cells.70

However, changes in the immunological homeostasis of CMV‐infected hosts do not necessarily impair immune responses and may even impart a boosting effect, particularly in younger individuals. Some published data imply that CMV in young humans – or young mice – may improve immune responses to selected antigens (other than CMV), including immune responses to influenza virus, probably by increased pro‐inflammatory responses.71, 72 CMV‐associated T‐cell expansion in young children does not impair naive T‐cell numbers or the maintenance of protective immune responses against non‐related pathogens, while expansion of effector memory cells resulted in a significant increase in the total number of CD8+ T cells.73 Human CMV infection appears to promote the polyfunctionality of CD8+ T cells, resulting in increased CD107a expression and interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) as well as TNF‐α production. This has been explored in CMV‐seropositive and CMV‐seronegative young individuals, as well as in CMV‐seropositive, middle‐aged healthy humans in response to staphylococcal enterotoxin B.71 A higher percentage of polyfunctional CD8+ T cells was identified in blood from young CMV‐seropositive individuals compared with CMV‐seronegative individuals. This is supported by the observation that CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells reside mainly among CCR7− CD45RO+ CD27+/− T cells in young adults, while more clonally expanded T cells are found in the CCR7− CD45A+ CD27− subset.63, 74, 75, 76 There is also compelling evidence from animal models showing that CMV protects from fatal infections with other pathogenic organisms.77 These preclinical studies showed that CMV may improve the function and consequently the quality of CD8+ T cells, at least in younger animals, a finding that may lend support to CMV being a critical factor in shaping ‘immune fitness’ to benefit younger individuals.

Sex is another important inherent factor that impacts immune responses, besides age.78 Although CMV seropositivity is higher in younger women than men, several studies indicate that the memory immune response to CMV may be dependent on the sex of individuals.79, 80 A predominant T helper type 1 antiviral cytokine T helper memory response, linked to sex, showed that females had higher and significantly stronger spontaneous CMV‐triggered IFN‐γ and IL‐2 production.81 van der Heiden et al.55 demonstrated that CMV‐positive males carry lower numbers of total CD4+, CD4+ central‐memory, and follicular helper T cells than females and CMV‐negative males. Moreover, reduced numbers of regulatory T cells and memory B cells were found in CMV‐positive males compared to CMV‐positive females. This could partly explain inverted CD4+/CD8+ T‐cell ratios and expanded CD45RA+ T effector‐memory subsets in older men.82, 83, 84

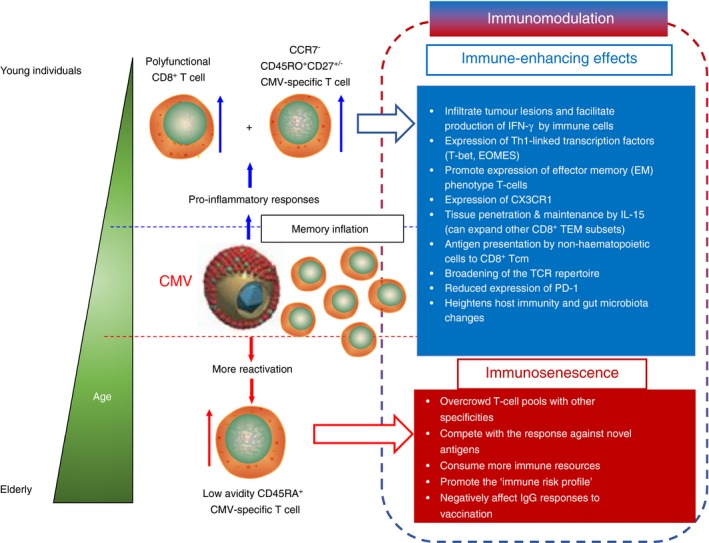

The findings discussed above indicate that the effect of CMV on the immune system may depend on individuals’ age, sex and environmental factors. Immunological ageing may therefore be viewed as ‘collateral damage’ from immune reactivity that was beneficial in earlier life (Fig. 1). Even in the elderly population, immunosurveillance against CMV may be advantageous and crucial for longevity; high numbers of naive/precursor T cells are not necessarily related to better survival.85 Hence, continued immunosurveillance against persistent CMV appears to be more critical for host survival than reserving immune resources for responses to other viruses11 or antigens that play a role in clinically relevant T‐cell responses directed against transformed cells.

Figure 1.

Summary of immune‐enhancing effects versus immunosenescence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) in an age‐dependent manner. The immunomodulatory effect of inflationary CMV‐specific memory T cells stretches across immunological niches, including long‐term memory T cells that express ‘stem cell‐like markers’. This affects regulation of the overall cellular immune repertoire, which causes shifts in immune recognition profiles, or leads to reduced survival of the inflationary T cells and potentially shapes the anti‐tumour cellular immune response in patients with cancer. As a direct or an indirect consequence, CMV‐driven inflationary T cells influence cellular immune responses either by immune‐enhancing effects (upper half of figure guided by blue‐outlined arrow) or immune‐decreasing/immunosenescent‐associated effects (lower half of figure guided by red‐outlined arrow) on T‐cell populations. Immune‐enhancement, as usually seen in younger individuals, may lead to a broader T‐cell receptor (TCR) repertoire, thus expansion of the number and origin (tumour versus pathogen‐derived) of epitopes recognized by T cells. Inevitably, these immune responses may collectively start necessary inflammation to ward off productive infections and/or initiation of tumours. The expression of CX3CR1, the fractalkine receptor that facilitates tissue homing, indicates that some population of CMV‐specific inflationary cells possess an enhanced ability to re‐seed organs as resident sentinel T‐cells. The establishment of immunosenescence among T cells particularly in elderly persons may not be reversed, unlike immune exhaustion, i.e. programmed cell‐death protein 1 (PD‐1) expression. This is perhaps one reason why inflationary T cells are not long‐lived. However, immunosenescent T cells are still able to ‘invade’ the memory T‐cell pool and thereby compete with TCRs of other specificities, which consequently skews the immune response profile of an individual. The immune risk profile (IRP), which is characterized by immune dysfunction and reduced overall survival, is also a consequence of immune‐senescence, and is in part linked to CMV‐specific inflationary T cells.

CMV‐specific memory inflation shapes global and anti‐tumour immune response in patients with cancer

Cytomegalovirus infection has not been well studied in patients with cancer, although a frequency of 2·2 cases per 1000 autopsies of CMV pneumonia at M. D. Anderson Cancer Centre was reported more than 20 years ago.86 Therefore, it is possible that CMV reactivation and disease are underestimated and under‐diagnosed in patients with cancer, as CMV testing is not routinely performed in these individuals. Emerging evidence suggests that CMV is highly prevalent in patients with breast, colon, prostate, liver, and cervical cancers, rhabdomyosarcoma, salivary gland tumours, or brain tumours.87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93 Most neoplastic cells in the sentinel lymph nodes of > 90% of patients with breast cancer have been shown to be CMV‐positive,94 whereas 98% of brain metastases of colon and breast cancers contain CMV proteins and/or nucleic acids.95 Conversely, CMV proteins are not detected in healthy tissues surrounding CMV‐positive tumours or metastases. Also, 9·3% of patients with cancer (not stem cell tranplant‐related) may experience CMV reactivation.96 In a retrospective analysis, approximately 50% of patients with solid tumours and CMV DNA positivity also had CMV disease requiring antiviral therapy.97 Reactivation in these patients during chemotherapy was not asymptomatic but was mostly self‐limiting.98, 99 However, CMV viraemia predicts high mortality (61·3%) in patients with cancer requiring mechanical ventilation.100 Gastrointestinal CMV disease is associated with high morbidity and mortality, although it is uncommon in patients with solid tumours.101 To clarify the role of CMV reactivation in patients with solid tumours, well‐designed prospective studies using modern diagnostic techniques and established definitions of CMV infection and disease are required.3

The question of whether clonal expansion of CMV‐specific immune cells reduces the ability of the immune system in patients with cancer to mount effective anti‐tumour responses needs to be addressed. Chen et al.102 investigated CMV‐specific immune responses in 101 patients with various types of cancer. The authors found that the level of CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells was significantly higher in blood from patients with stage IV cancer and an extensive treatment history. Of note, plasma levels of IL‐6 were increased in association with disease progression, whereas IL‐7 levels did not significantly differ. A relatively decreased population of naive/precursor T cells was suggested to be linked with down‐regulation of the IL‐7 receptor α chain,102 an observation that was also found in patients with breast cancer in association with CMV infection.102, 103 Apoptosis‐resistant, terminally differentiated CMV‐tetramer+ CD28− CD8+ T‐cell frequencies were also markedly elevated in blood from patients who had undergone extensive cancer therapies. This study demonstrated that the proportion of CMV‐specific T cells increased in blood from patients with cancer as the disease progressed. In contrast, over the last 10 years, many studies have also shown that positive CMV serology or reactivation may confer beneficial effects against leukaemia relapse, especially in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia undergoing allo‐HSCT,104, 105, 106, 107 although this finding is still conflicting.108 One possible explanation is that CMV infection could ‘educate’ specific immune‐cell subsets, e.g. γδ T cells to mediate cancer regression.109 These T cells were capable of recognizing both CMV‐infected cells and primary leukaemic blasts in HSCT recipients,109 in addition to being associated with a reduced cancer risk after kidney transplantation.110

Glioblastoma multiforme

The prevalence of CMV positivity approaches 100% in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) tissue,87, 88, 111 although this finding remains somewhat controversial.112, 113 Stimulation of autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with GBM tumour lysates leads to expansion of CMV‐specific T cells in blood from patients with GBM, which can kill autologous GBM cells in vitro.91, 114 Although patients with GBM exhibited a similar number of CMV‐specific T cells in PBMC compared to healthy donors, the majority of CMV‐specific T cells in the patients were dysfunctional, but could be reverted to functionality by ex vivo expansion.115 Most CMV‐specific T cells in PBMC from patients with GBM expressed CD57 (a marker for terminal differentiation and activation). These T cells were unable to produce multiple cytokines and displayed limited cytolytic function.115 Patients with GBM exhibited a lower frequency of CD3+ T cells compared to healthy individuals but had significantly higher numbers of CD4+ CD28− T cells before, and after 3 and 12 weeks after surgery in addition to increased levels of CD4+ CD57+ and CD4+ CD57+ CD28+ T cells at all time‐points measured.116 These T‐cell subsets have been associated with both immunosenescence and CMV infection, as CD57 expression increases with age117, 118, 119 and in patients with cancer.120 Furthermore, CMV‐specific CD57+ CD4+ T cells may also represent a mature cellular subset capable of up‐regulating surface CD107a expression (a degranulation marker), although their ability to lyse virus‐infected cells may be compromised due to reduced intracellular content of cytotoxic granules.119 These findings suggest that markers of immunosenescence in the CD4+ compartment are likely to be associated with poor survival in patients with CMV‐positive GBM and may reflect CMV activity in transformed tissue.116 However, other reports examining tumour‐infiltrating lymphocytes and in PBMC from patients with cancer show that ‘exhausted’ T cells, e.g. defined by PD‐1 expression, may in fact represent antigen‐specific T cells that had more recently encountered their nominal target antigen.121, 122

Expression of CMV antigens in GBM tissues may provide the opportunity to target viral antigens for GBM therapy. Combination therapy with autologous CMV‐specific T cells and chemotherapy may be safe and potentially offers clinical benefits for patients with recurrent GBM.123 Compelling evidence comes from a recently reported randomized clinical trial of CMV pp65‐directed dendritic cell (DC) ‐based immunotherapy administered to patients with GBM following preconditioning with either mature DC or tetanus/diphtheria toxoid unilaterally, before bilateral vaccination with DC pulsed with pp65 RNA. The authors reported that patients given tetanus/diphtheria toxoid had enhanced DC migration, and significantly improved progression‐free and overall survival that exceeded 40 months (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00639639).124 Another recent clinical study showed that patients with GBM who received anti‐CMV adoptive cell transfer exhibited even better cellular immune responses further to an improved survival pattern following vaccination with a CMVpp65 RNA‐pulsed DC vaccine candidate.125 Prolonged treatment with valganciclovir as an adjunct to standard therapy has been shown to benefit patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent GBM, although randomized trials are warranted in the future.126, 127, 128 It is, however, worthwhile to examine in future studies whether antiviral therapy may also benefit patients with GBM through additional immune‐related pathways, based on the clinical case of a patient with ependymoma, who after ganciclovir treatment showed enhanced innate immune and T‐cell activation.129 This demonstrates that infusion of functional CMV‐specific T cells or antiviral drugs may benefit patients with CMV‐associated cancers, aided by the ‘trans’ effect of CMV‐specific T cells, i.e. that TNF‐α or IFN‐γ production may impact on cancer cells, either directly or indirectly by increasing visibility to the immune system by up‐regulating the HLA class I and class II APM.

Colorectal cancer

Several studies have identified CMV in colorectal cancer (CRC) tissue; about ~ 40% of CRC specimens generally test CMV positive.89, 130, 131, 132 A recent meta‐analysis suggested a statistical association between CMV infection and an increased risk of CRC.133 In patients with CRC, CMV RNA transcripts and protein appear to be specifically localized to the cytoplasm of neoplastic mucosal epithelium compared with non‐transformed cells.132, 134 The presence of CMV in tumour tissue is associated with an unfavourable outcome in elderly patients with CRC and predicts poor disease‐free survival independent of TNM staging.135 It is noteworthy that tumoral presence of CMV correlates with clinical outcome in CRC more closely than the traditional histopathological tumour staging method. Additionally, higher transcription of IL‐17 was found in CMV‐positive tumours,135 which correlates with a poor outcome of CRC.136, 137 On the contrary, presence of CMV in CRC tumours among patients < 65 years of age independently predicted a higher disease‐free survival rate based on multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis.138 In this study, significant intra‐tumoral inflammatory responses were more frequently observed in CMV‐positive tumours with lower levels of IL‐1, a pleiotropic cytokine implicated in promoting tumour growth, angiogenesis and potentially metastasis.139, 140 Taken together, CMV may enhance immunity to cancer in younger patients whereas long‐term CMV infection may be detrimental to clinically relevant anti‐tumour immune responses in older individuals (Fig. 1).

Other cancers

There is a significant amount of data concerning immunosuppression in patients with cancer, caused by the interaction of tumour cells with immune cells leading to lymphocyte dysfunction or death.141 However, it is unclear whether this immunosuppression is universal or restricted to immune responses targeting tumour antigens. Recent data in CMV‐infected human cells showed that UL148‐induced down‐regulation of CD58 (a cell surface molecule important for co‐stimulation of effector T cells) leads to dampening of a productive immune response, which includes loss of cytotoxic activity by cytotoxic lymphocytes and natural killer cells.142 This may be augmented with down‐regulation of APM‐associated components to subdue the immune response.143, 144 This may represent a general mechanism of immune suppression employed by CMV which may also be relevant to cancer. In contrast to data obtained from patients with GBM, several reports showed anergy of tumour‐specific T cells in patients with melanoma, whereas CMV‐specific T cells in the same patients were functional.145, 146, 147, 148, 149 In patients with melanoma, frequencies of TIM‐3+ cells among NY‐ESO‐1‐specific CD8+ T cells (mean 28·8% ± 20·7%) were significantly higher than those of CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells (8·8 ± 4·9%),148 whereas the expression and distribution of BTLA, PD‐1 and TIM‐3 on CMV‐specific and total CD8+ T cells were similar to those of healthy donors.148, 149 Similarly, the frequency of CMV‐specific T cells in blood from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma was unaffected after treatment as opposed to those of tumour‐associated antigen (TAA)‐specific T cells, which were elevated.150, 151, 152 In further detail, CMV‐specific T cells expanded in vitro from PBMC of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma strongly expressed PD‐1, but not TIM‐3 and produced IFN‐γ, while expanded TAA (peptide)‐specific T cells failed to induce production of IFN‐γ, with highly varied expression levels of both inhibitory receptors.153 Inokuma et al.154 found that CMV‐specific T cells were significantly present at higher frequencies compared with tumour‐specific T cells in CMV‐positive patients with breast cancer. Interestingly, CMV‐specific T cells produced less IL‐2 but higher amounts of IFN‐γ, but the opposite was true for tumour‐reactive T cells. The ability to respond with IL‐2 and IFN‐γ may also reflect the antigen dose available to T cells in their immediate microenvironment for optimal TCR stimulation.155 Also, PD‐1 inhibition may be a viable therapeutic strategy to treat chronic infectious diseases, as was recently reviewed by Rao et al.156

From the current but limited data, it seems that CMV‐specific T cells are functional, express fewer exhaustion markers, and are maintained at ‘normal’ levels irrespective of treatment, compared with tumour‐antigen‐reactive T cells in blood from patients with a variety of cancers except GBM (Table 1). However, CMV infection (and the associated immune response) may not merely impose a ‘bystander effect’, considering the high frequency of inflationary CMV‐specific T cells found in patients with cancer. More studies are needed to address this point; cleverly designed clinical programmes that incorporate comprehensive immunological analyses may, therefore, help to understand the nature of immune responses in patients with cancer in greater detail. An interesting study by Chang et al.157 showed that in vitro ganciclovir treatment triggered an increase in early differentiated T‐cell frequencies accompanied by a decrease in the percentage of effector‐memory T cells in blood from patients with cancer. Furthermore, this treatment improved the T cells’ ability to kill tumour cells, accompanied by PD‐1 down‐regulation. A recent clinical study showed that ganciclovir treatment of CMV‐positive patients with sepsis does not affect serum IL‐6 levels while reducing the incidence of CMV reactivation, indicating that the drug does not have anti‐inflammatory effects.158 Although ganciclovir is not CMV‐specific, this observation prompts the discussion that many drugs used in clinical settings may have multiple functions and could therefore be repurposed for host‐directed therapy.159 Whether anti‐CMV treatment/adoptive T‐cell therapy could benefit patients with cancers by directly killing CMV‐associated cancer cells is a formally testable question. Table 2 lists immunotherapeutic approaches currently in clinical trials and serves as evidence that CMV‐targeting immune‐based interventions may provide a safe, novel treatment option while offering clinical benefit to patients with GBM. It may also be possible to use CMV as an immunomodulator to modify the global and anti‐tumour immune landscape, supported by observations where prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination with recombinant MCMV vectors show some efficacy in preclinical models of prostate cancer160 and melanoma,161, 162, 163 although exploration of CMV‐based vaccines for cancer is in its infancy.

Table 1.

Cytomegalovirus‐specific and tumour‐associated antigen‐specific immune response in patients with cancer

| Group/Reference | Tumour site | Sample size | CMV‐specific immune response | TAA‐specific immune response | Impact on clinical outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Phenotype/Function | Frequency | Phenotype/Function | ||||

| Crough et al.115 | Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) | 27 | 0·1–22% of CD8+ T cells in all seropositive GBM patients, which was comparable to that seen in healthy CMV‐seropositive individuals. The cell frequency was not affected by anticancer therapy and dexamethasone therapy | CD57+; MIP‐1β − TNF‐α − IFN‐γ −; CD107alo; in vitro stimulation with CMV peptide epitopes in the presence of γC cytokine dramatically reversed the polyfunctional profile of these antigen‐specific T cells | NR | NR | Adoptive transfer of these in‐vitro‐expanded CMV‐specific T cells in combination with temozolomide (TMZ) therapy into a patient with recurrent GBM was coincident with long‐term disease‐free survival |

| Mizukoshi et al.150 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 31 | CMV‐specific T‐cell response rates (12–92/300 000 PBMC) were similar among patients with cancer and healthy donors. The frequency of CMV‐specific T cells increased in 4 of 12 patients after treatments | NR | 10–60·5 cells/300 000 PBMC. The frequency of TAA‐specific T cells increased in all patients after treatment | CD45RA−/CCR7+ central‐memory T cells was the highest | NR |

| Flecken et al.153 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 96 | NR | Can be specifically expanded in vitro and can produce IFN‐γ in these cell lines; strongly expressed PD‐1 but not TIM‐3 | NR | Can be specifically expanded in vitro but failed to detect production of IFN‐γ in these cell lines; very heterogeneous expression levels of both inhibitory receptors | NR |

| Mizukoshi et al.151 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 69 | 11·9% of patients increased after intervention | NR | 39·3–62·3% of patients increased after treatment (Before treatment: 0·00–0·03% of CD8+; After treatment: 0·00–0·10% of CD8+). The frequencies of TAA‐derived peptide‐specific T cells decreased in most of the patients at 24 weeks after RFA, while the frequencies of CMV‐derived peptide‐specific T cells were maintained in most of the patients | The frequency of tetramer‐positive cells with CD45RA−/CCR7+ and CD45RA−/CCR7− profiles was increased in 6/7 (85·7%) of patients, respectively. The tetramer‐positive cells with CD45RA−/CCR7+ were newly induced after RFA in 5/7 (71·4%) patients | Increased TAA‐specific T cells after treatment correlated with length of recurrence‐free survival, while no correlation between the number of TAA‐specific T cells before treatment and recurrence‐free survival |

| Mizukoshi et al.152 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 14 | 98 and 104 per 3 × 105 PBMC pre‐ and post‐vaccination in one patient. The frequencies of CMV‐specific CTL did not decrease during the study course in most of the patients | NR | The frequencies of hTERT461 peptide‐specific CTLs were 0 and 35 per 3 × 105 PBMC/0·04% and 0·12% of CD8+ T cells pre‐ and post‐vaccination, respectively | hTERT461 peptide vaccination increased the proportion of peptide‐specific effector‐memory phenotype CTLs. Phenotypic analysis of total CD8+ T cells before and after vaccination showed no increase in the frequency of CD45RA−/CCR7− T cells | NR |

| Lee et al.145 | Melanoma | 11 | 0·91–0·64% of CD8+ | Displayed up‐regulation of CD69 after antigen stimulation | MART‐specific CD8+: 0·014–0·16%; tyrosinase‐specific CD8+: 0·19–2·2% | MART‐specific CD8+: CD8β hi CD16− CD27+ CD28+CD44bright CD45RO+ CD45rA−; tyrosinase‐specific CD8+: CD8β hi CD16+ CD38+ CD44dull CD45RO− CD45RA+ CD57−; minimal or no up‐regulation of CD69 after antigen stimulation | NR |

| Walker et al.146 | Melanoma | 16 | 0·05–0·5% | NR | gp100‐specific LTM CD8+ T cells: 0·02–0·2% | Homologous to those of CMV‐specific memory T cells | NR |

| Chauvin et al.147 | Melanoma | 8 | NR | Frequency of TIGIT+ cells among CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells was 45·4% ± 26·7%. CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells were predominantly TIGIT− PD‐1− (50·2% ± 23·7%) | NR | 90·7% ± 4·1% of A2/NY‐ESO‐1–specific CD8+ T cells expressing TIGIT. The majority of NY‐ESO‐1–specific CD8+ T cells co‐expressed TIGIT and PD‐1 (83% ± 7·8%) | NR |

| Fourcade et al.148 | Melanoma | 11 | NR | CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells in patients were either BTLA− PD‐1− Tim‐3− or BTLA− PD‐1+ Tim‐3− and displayed very low frequencies of BTLA+ PD‐1+ Tim‐3+ and BTLA+ PD‐1+ Tim‐3− cells – similar to healthy donors | 60·4% ± 17% of NY‐ESO‐1–specific CD8+ T cells were BTLA+ | 25·2% ± 29·3% of CMV‐specific were BTLA+. BTLA+ PD‐1+ Tim‐3− (42·7% ± 16·4%) represented the largest NY‐ESO‐1–specific CD8+ T‐cell subset | NR |

| Fourcade et al.149 | Melanoma | 9 | NR | 8·8 ± 4·9% of CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells were TIM‐3+, while 6·8 ± 3·2% of those in healthy donors were TIM‐3+ | NR | 28·8% ± SD 20·7% of NY‐ESO‐1‐specific CD8+ T cells were Tim‐3+ | NR |

| Inokuma et al.154 | Breast cancer | 21 | Significantly higher than TAA in CMV‐positive patients | Less IL‐2 production with more IFN‐γ production, broadly distributed and contained a high proportion of CD27− CD28− CD45RA+ T cells | CD4+ IL‐2+: 0·03–0·04%; CD8+ IL‐2+: 0·018–0·035% | TAA‐responsive CD8+: CD28+ CD45RA−; More IL‐2 production with less IFN‐γ production | NR |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; TAA, tumour‐associated antigens; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; PD‐1, programmed cell death protein‐1; TIM‐3, T‐cell immunoglobulin and mucin‐domain 3; TIGIT, T‐cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain; Ag, antigen; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; NR, not reported.

Table 2.

Current clinical trials using cytomegalovirus‐targeting immunotherapy for patients with glioblastoma (accessed on 2 May 2018, ClinicalTrials.gov)

| Intervention | Cancer type | Enrolment | Phase | Duration | NCT number | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety and tolerability of VBI‐1901 vaccine candidate in patients with recurrent GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) | 18 | I/II | 2017–2019 | NCT03382977 | Recruiting |

| Autologous cytomegalovirus‐specific cytotoxic T cells combined with temozolomide (TMZ) | GBM | 54 | I/II | 2016–2020 | NCT02661282 | Recruiting |

| Genetically‐modified HER‐CAR CMV‐specific CTLs | GBM | 16 | I | 2010–2028 | NCT01109095 | Active, not recruiting |

| TMZ+ cytomegalovirus peptide (PEP‐CMV) vaccine | GBM | 45 | I | 2016–2018 | NCT02864368 | Recruiting |

| Cytomegalovirus pp65‐LAMP mRNA‐loaded dendritic cells (DC) with or without autologous lymphocyte transfer, tetanus toxoid | Newly diagnosed GBM (ATTAC‐I) | 16 | I | 2006–2018 | NCT00639639 | Active, not recruiting |

| pp65‐shLAMP DC with GM‐CSF | Newly diagnosed GBM (ATTAC‐II) | 150 | II | 2016–2024 | NCT02465268 | Recruiting |

| Temozolomide + human CMV pp65‐LAMP mRNA‐pulsed autologous DC | Newly diagnosed GBM | 116 | II | 2015–2020 | NCT02366728 | Recruiting |

| RNA‐loaded dendritic cell vaccine + basiliximab | Newly Diagnosed GBM | 18 | I | 2007–2018 | NCT00626483 | Active, not recruiting |

HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; HER‐CAR, HER chimeric receptor; LAMP, lysosome‐associated membrane protein; GM‐CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor.

Conclusions

Cytomegalovirus has a profound influence on the global and antigen‐specific immune signatures, not only in immunosuppressed individuals, but also in the immunocompetent host. Strong cellular immune responses in blood directed against CMV or Epstein–Barr virus antigens at diagnosis can predict better survival among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis,164 serving as a marker for ‘T‐cell fitness’ – representing prevalent anti‐CMV responses. We now have a better picture of how the unique immunological memory inflation driven by CMV is initiated and controlled, as well as its association with age, sex and environmental factors. Although not common, inflationary CMV pp65‐specific CD4+ T cells that can express granzyme B from HIV‐positive/CMV‐positive individuals have also been described, thus expanding the immune repertoire of inflationary responses to CMV infection165 as well as their role in mediating immunopathology. Targeting CMV could potentially represent a biologically viable immunomodulator; harnessing clinically relevant immune responses may, therefore, pave the way for developing cutting‐edge immunotherapies for patients with malignancies (for a summary of ongoing clinical trials see Table 1).

Funding

The first author was supported by a scholarship from China Scholarship Council (CSC), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81100388, grant 81470344), and the Medical Scientific Research Programme of Chongqing Health and Family Planning Commission (grant 20142014).

Disclosures

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author contributions

X‐HL wrote the first draft of the manuscript, conducted the literature search, reviewed the abstracts, performed analysis and contributed to the final draft; MR contributed to revising the manuscript and provided scientific input. ED revised the manuscript. MM initiated, designed and supervised the study, revised and wrote the final draft, and contributed to the analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol 2010; 20:202–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGeoch DJ, Dolan A, Ralph AC. Toward a comprehensive phylogeny for mammalian and avian herpesviruses. J Virol 2000; 74:10401–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ljungman P, Boeckh M, Hirsch HH, Josephson F, Lundgren J, Nichols G et al Definitions of CMV infection and disease in transplant patients for use in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 64:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luo X‐H, Chang Y‐J, Huang X‐J. Improving cytomegalovirus‐specific T cell reconstitution after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. J Immunol Res 2014; 2014:631951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luo X‐H, Huang X‐J, Liu K‐Y, Xu L‐P, Liu D‐H. Protective immunity transferred by infusion of cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8+ T cells within donor grafts: its associations with cytomegalovirus reactivation following unmanipulated allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16:994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sierro S, Rothkopf R, Klenerman P. Evolution of diverse antiviral CD8+ T cell populations after murine cytomegalovirus infection. Eur J Immunol 2005; 35:1113–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F et al Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus‐specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med 2005; 202:673–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Torti N, Walton SM, Brocker T, Rülicke T, Oxenius A. Non‐hematopoietic cells in lymph nodes drive memory CD8 T cell inflation during murine cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS Pathog 2011; 7:e1002313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Leeuwen EM, Remmerswaal EB, Vossen MT, Rowshani AT, Wertheim‐van Dillen PM, van Lier RA et al Emergence of a CD4+ CD28− granzyme B+, cytomegalovirus‐specific T cell subset after recovery of primary cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol 2004; 173:1834–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Blomberg BB. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) seropositivity decreases B cell responses to the influenza vaccine. Vaccine 2015; 33:1433–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brodin P, Jojic V, Gao T, Bhattacharya S, Angel CJL, Furman D et al Variation in the human immune system is largely driven by non‐heritable influences. Cell 2015; 160:37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Hara GA, Welten SP, Klenerman P, Arens R. Memory T cell inflation: understanding cause and effect. Trends Immunol 2012; 33:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holtappels R, Pahl‐Seibert M‐F, Thomas D, Reddehase MJ. Enrichment of immediate‐early 1 (m123/pp89) peptide‐specific CD8 T cells in a pulmonary CD62Llo memory‐effector cell pool during latent murine cytomegalovirus infection of the lungs. J Virol 2000; 74:11495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karrer U, Sierro S, Wagner M, Oxenius A, Hengel H, Koszinowski UH et al Memory inflation: continuous accumulation of antiviral CD8+ T cells over time. J Immunol 2003; 170:2022–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snyder CM, Cho KS, Bonnett EL, van Dommelen S, Shellam GR, Hill AB. Memory inflation during chronic viral infection is maintained by continuous production of short‐lived, functional T cells. Immunity 2008; 29:650–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munks MW, Cho KS, Pinto AK, Sierro S, Klenerman P, Hill AB. Four distinct patterns of memory CD8 T cell responses to chronic murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol 2006; 177:450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paul K. The (gradual) rise of memory inflation. Immunol Rev 2018; 283:99–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Čičin‐Šain L, Sylwester AW, Hagen SI, Siess DC, Currier N, Legasse AW et al Cytomegalovirus‐specific T cell immunity is maintained in immunosenescent rhesus macaques. J Immunol 2011; 187:1722–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lelic A, Verschoor CP, Ventresca M, Parsons R, Evelegh C, Bowdish D et al The polyfunctionality of human memory CD8+ T cells elicited by acute and chronic virus infections is not influenced by age. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1003076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wallace DL, Masters JE, De Lara CM, Henson SM, Worth A, Zhang Y et al Human cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8+ T‐cell expansions contain long‐lived cells that retain functional capacity in both young and elderly subjects. Immunology 2011; 132:27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hansen SG, Ford JC, Lewis MS, Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Coyne‐Johnson L et al Profound early control of highly pathogenic SIV by an effector memory T‐cell vaccine. Nature 2011; 473:523–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hansen SG, Piatak M Jr, Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Gilbride RM, Ford JC et al Immune clearance of highly pathogenic SIV infection. Nature 2013; 502:100–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bottcher JP, Beyer M, Meissner F, Abdullah Z, Sander J, Hochst B et al Functional classification of memory CD8+ T cells by CX3CR1 expression. Nat Commun 2015; 6:8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ouyang Q, Wagner WM, Wikby A, Walter S, Aubert G, Dodi AI et al Large numbers of dysfunctional CD8+ T lymphocytes bearing receptors for a single dominant CMV epitope in the very old. J Clin Immunol 2003; 23:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pera A, Vasudev A, Tan C, Kared H, Solana R, Larbi A. CMV induces expansion of highly polyfunctional CD4+ T cell subset coexpressing CD57 and CD154. J Leukoc Biol 2016; 101:555–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arens R, Wang P, Sidney J, Loewendorf A, Sette A, Schoenberger SP et al Cutting edge: murine cytomegalovirus induces a polyfunctional CD4 T cell response. J Immunol 2008; 180:6472–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verma S, Weiskopf D, Gupta A, McDonald B, Peters B, Sette A et al Cytomegalovirus‐specific CD4 T cells are cytolytic and mediate vaccine protection. J Virol 2016; 90:650–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walton SM, Torti N, Mandaric S, Oxenius A. T‐cell help permits memory CD8+ T‐cell inflation during cytomegalovirus latency. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41:2248–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Welten SP, Redeker A, Franken KL, Benedict CA, Yagita H, Wensveen FM et al CD27–CD70 costimulation controls T cell immunity during acute and persistent cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol 2013; 87:6851–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Humphreys IR, Loewendorf A, De Trez C, Schneider K, Benedict CA, Munks MW et al OX40 costimulation promotes persistence of cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8 T cells: a CD4‐dependent mechanism. J Immunol 2007; 179:2195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Humphreys IR, Lee SW, Jones M, Loewendorf A, Gostick E, Price DA et al Biphasic role of 4‐1BB in the regulation of mouse cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40:2762–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bachmann MF, Wolint P, Walton S, Schwarz K, Oxenius A. Differential role of IL‐2R signaling for CD8+ T cell responses in acute and chronic viral infections. Eur J Immunol 2007; 37:1502–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beswick M, Pachnio A, Lauder SN, Sweet C, Moss PA. Antiviral therapy can reverse the development of immune senescence in elderly mice with latent cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol 2013; 87:779–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Redeker A, Welten SP, Arens R. Viral inoculum dose impacts memory T‐cell inflation. Eur J Immunol 2014; 44:1046–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trgovcich J, Kincaid M, Thomas A, Griessl M, Zimmerman P, Dwivedi V et al Cytomegalovirus reinfections stimulate CD8 T‐memory inflation. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0167097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ross SA, Arora N, Novak Z, Fowler KB, Britt WJ, Boppana SB. Cytomegalovirus reinfections in healthy seroimmune women. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:386–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hertoghs KM, Moerland PD, van Stijn A, Remmerswaal EB, Yong SL, van de Berg PJ et al Molecular profiling of cytomegalovirus‐induced human CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Clin Investig 2010; 120:4077–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meijers R, Litjens N, Hesselink D, Langerak A, Baan C, Betjes M. Primary cytomegalovirus infection significantly impacts circulating T cells in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2015; 15:3143–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miles DJ, van der Sande M, Jeffries D, Kaye S, Ismaili J, Ojuola O et al Cytomegalovirus infection in Gambian infants leads to profound CD8 T‐cell differentiation. J Virol 2007; 81:5766–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xu W, Larbi A. Markers of T cell senescence in humans. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18:E1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Larbi A, Fulop T. From, “truly naive” to “exhausted senescent” T cells: when markers predict functionality. Cytometry A 2014; 85:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crespo J, Sun H, Welling TH, Tian Z, Zou W. T cell anergy, exhaustion, senescence, and stemness in the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Immunol 2013; 25:214–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klenerman P, Oxenius A. T cell responses to cytomegalovirus. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:367–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kallemeijn MJ, Boots AMH, van der Klift MY, Brouwer E, Abdulahad WH, Verhaar JAN et al Ageing and latent CMV infection impact on maturation, differentiation and exhaustion profiles of T‐cell receptor γδ T‐cells. Sci Rep 2017; 7:5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dekhtiarenko I, Ratts RB, Blatnik R, Lee LN, Fischer S, Borkner L et al Peptide processing is critical for T‐cell memory inflation and may be optimized to improve immune protection by CMV‐based vaccine vectors. PLoS Pathog 2016; 12:e1006072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Baumann NS, Torti N, Welten SPM, Barnstorf I, Borsa M, Pallmer K et al Tissue maintenance of CMV‐specific inflationary memory T cells by IL‐15. PLoS Pathog 2018; 14:e1006993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bains I, Antia R, Callard R, Yates AJ. Quantifying the development of the peripheral naive CD4+ T‐cell pool in humans. Blood 2009; 113:5480–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen G, Yang X, Ko A, Sun X, Gao M, Zhang Y et al Sequence and structural analyses reveal distinct and highly diverse human CD8+ TCR repertoires to immunodominant viral antigens. Cell Rep 2017; 19:569–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Biasco L, Scala S, Basso Ricci L, Dionisio F, Baricordi C, Calabria A et al In vivo tracking of T cells in humans unveils decade‐long survival and activity of genetically modified T memory stem cells. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:273ra13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Successful and maladaptive T cell aging. Immunity 2017; 46:364–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Poiret T, Axelsson‐Robertson R, Remberger M, Luo XH, Rao M, Nagchowdhury A et al Cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8+ T‐cells with different T‐cell receptor affinities segregate T‐cell phenotypes and correlate with chronic graft‐versus‐host disease in patients post‐hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol 2018; 9:760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Miles DJ, van der Sande M, Jeffries D, Kaye S, Ojuola O, Sanneh M et al Maintenance of large subpopulations of differentiated CD8 T‐cells two years after cytomegalovirus infection in Gambian infants. PLoS One 2008; 3:e2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Looney R, Falsey A, Campbell D, Torres A, Kolassa J, Brower C et al Role of cytomegalovirus in the T cell changes seen in elderly individuals. Clin Immunol 1999; 90:213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vescovini R, Telera AR, Pedrazzoni M, Abbate B, Rossetti P, Verzicco I et al Impact of persistent cytomegalovirus infection on dynamic changes in human immune system profile. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0151965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van der Heiden M, van Zelm MC, Bartol SJ, de Rond LG, Berbers GA, Boots AM et al Differential effects of cytomegalovirus carriage on the immune phenotype of middle‐aged males and females. Sci Rep 2016; 6:26892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Motz GT, Coukos G. Deciphering and reversing tumor immune suppression. Immunity 2013; 39:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Smith CJ, Turula H, Snyder CM. Systemic hematogenous maintenance of memory inflation by MCMV infection. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Waller EC, McKinney N, Hicks R, Carmichael AJ, Sissons JP, Wills MR. Differential costimulation through CD137 (4‐1BB) restores proliferation of human virus‐specific “effector memory”(CD28− CD45RAhi) CD8+ T cells. Blood 2007; 110:4360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Larbi A, Strindhall J, Wikby A. Cytomegalovirus and human immunosenescence. Rev Med Virol 2009; 19:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hadrup SR, Strindhall J, Køllgaard T, Seremet T, Johansson B, Pawelec G et al Longitudinal studies of clonally expanded CD8 T cells reveal a repertoire shrinkage predicting mortality and an increased number of dysfunctional cytomegalovirus‐specific T cells in the very elderly. J Immunol 2006; 176:2645–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stowe RP, Kozlova EV, Yetman DL, Walling DM, Goodwin JS, Glaser R. Chronic herpesvirus reactivation occurs in aging. Exp Gerontol 2007; 42:563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Griffiths SJ, Riddell NE, Masters J, Libri V, Henson SM, Wertheimer A et al Age‐associated increase of low‐avidity cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8+ T cells that re‐express CD45RA. J Immunol 2013; 190:5363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, Klenerman P, Gillespie GM, Papagno L et al Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med 2002; 8:379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Appay V, van Lier RA, Sallusto F, Roederer M. Phenotype and function of human T lymphocyte subsets: consensus and issues. Cytometry A 2008; 73:975–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Derhovanessian E, Maier AB, Hähnel K, McElhaney JE, Slagboom EP, Pawelec G. Latent infection with cytomegalovirus is associated with poor memory CD4 responses to influenza A core proteins in the elderly. J Immunol 2014; 193:3624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Khan N, Hislop A, Gudgeon N, Cobbold M, Khanna R, Nayak L et al Herpesvirus‐specific CD8 T cell immunity in old age: cytomegalovirus impairs the response to a coresident EBV infection. J Immunol 2004; 173:7481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cicin‐Sain L, Brien JD, Uhrlaub JL, Drabig A, Marandu TF, Nikolich‐Zugich J. Cytomegalovirus infection impairs immune responses and accentuates T‐cell pool changes observed in mice with aging. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Smithey MJ, Li G, Venturi V, Davenport MP, Nikolich‐Žugich J. Lifelong persistent viral infection alters the naive T cell pool, impairing CD8 T cell immunity in late life. J Immunol 2012; 189:5356–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Komatsu H, Inui A, Sogo T, Fujisawa T, Nagasaka H, Nonoyama S et al Large scale analysis of pediatric antiviral CD8+ T cell populations reveals sustained, functional and mature responses. Immun Ageing 2006; 3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hassouneh F, Lopez‐Sejas N, Campos C, Sanchez‐Correa B, Tarazona R, Pera A et al Effect of cytomegalovirus (CMV) and ageing on T‐Bet and eomes expression on T‐cell subsets. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18:1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pera A, Campos C, Corona A, Sanchez‐Correa B, Tarazona R, Larbi A et al CMV latent infection improves CD8+ T response to SEB due to expansion of polyfunctional CD57+ cells in young individuals. PLoS One 2014; 9:e88538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Furman D, Jojic V, Sharma S, Shen‐Orr SS, Angel CJ, Onengut‐Gumuscu S et al Cytomegalovirus infection enhances the immune response to influenza. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:281ra43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. van den Heuvel D, Jansen MA, Dik WA, Bouallouch‐Charif H, Zhao D, van Kester KA et al Cytomegalovirus‐and Epstein–Barr virus‐induced T‐cell expansions in young children do not impair naive T‐cell populations or vaccination responses: the generation R study. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Derhovanessian E, Maier AB, Hähnel K, Beck R, de Craen AJ, Slagboom EP et al Infection with cytomegalovirus but not herpes simplex virus induces the accumulation of late‐differentiated CD4+ and CD8+ T‐cells in humans. J Gen Virol 2011; 92:2746–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chiu Y‐L, Lin C‐H, Sung B‐Y, Chuang Y‐F, Schneck JP, Kern F et al Cytotoxic polyfunctionality maturation of cytomegalovirus‐pp65‐specific CD4+ and CD8+ T‐cell responses in older adults positively correlates with response size. Sci Rep 2016; 6:19227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bajwa M, Vita S, Vescovini R, Larsen M, Sansoni P, Terrazzini N et al Functional diversity of cytomegalovirus‐specific T cells is maintained in older people and significantly associated with protein specificity and response size. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1430–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Barton ES, White DW, Cathelyn JS, Brett‐McClellan KA, Engle M, Diamond MS et al Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature 2007; 447:326–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bupp MRG. Sex, the aging immune system, and chronic disease. Cell Immunol 2015; 294:102–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Green MS, Cohen D, Slepon R, Robin G, Wiener M. Ethnic and gender differences in the prevalence of anti‐cytomegalovirus antibodies among young adults in Israel. Int J Epidemiol 1993; 22:720–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. De Mattia D, Stroffolini T, Arista S, Pistoia D, Giammanco A, Maggio M et al Prevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in Italy. Epidemiol Infect 1991; 107:421–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Villacres MC, Longmate J, Auge C, Diamond DJ. Predominant type 1 CMV‐specific memory T‐helper response in humans: evidence for gender differences in cytokine secretion. Hum Immunol 2004; 65:476–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Strindhall J, Skog M, Ernerudh J, Bengner M, Löfgren S, Matussek A et al The inverted CD4/CD8 ratio and associated parameters in 66‐year‐old individuals: the Swedish HEXA immune study. Age (Dordr) 2013; 35:985–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Amadori A, Zamarchi R, De Silvestro G, Forza G, Cavatton G, Danieli GA et al Genetic control of the CD4/CD8 T‐cell ratio in humans. Nat Med 1995; 1:1279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hirokawa K, Utsuyama M, Hayashi Y, Kitagawa M, Makinodan T, Fulop T. Slower immune system aging in women versus men in the Japanese population. Immun Ageing 2013; 10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Derhovanessian E, Maier AB, Hähnel K, Zelba H, de Craen AJ, Roelofs H et al Lower proportion of naive peripheral CD8+ T cells and an unopposed pro‐inflammatory response to human cytomegalovirus proteins in vitro are associated with longer survival in very elderly people. Age (Dordr) 2013; 35:1387–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mera JR, Whimbey E, Elting L, Preti A, Luna MA, Bruner JM et al Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in adult nontransplantation patients with cancer: review of 20 cases occurring from 1964 through 1990. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22:1046–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Baryawno N, Rahbar A, Wolmer‐Solberg N, Taher C, Odeberg J, Darabi A et al Detection of human cytomegalovirus in medulloblastomas reveals a potential therapeutic target. J Clin Investig 2011; 121:4043–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cobbs CS, Harkins L, Samanta M, Gillespie GY, Bharara S, King PH et al Human cytomegalovirus infection and expression in human malignant glioma. Can Res 2002; 62:3347–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Harkins L, Volk AL, Samanta M, Mikolaenko I, Britt WJ, Bland KI et al Specific localisation of human cytomegalovirus nucleic acids and proteins in human colorectal cancer. Lancet 2002; 360:1557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Harkins LE, Matlaf LA, Soroceanu L, Klemm K, Britt WJ, Wang W et al Detection of human cytomegalovirus in normal and neoplastic breast epithelium. Herpesviridae 2010; 1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ghazi A, Ashoori A, Hanley P, Salsman VS, Shaffer DR, Kew Y et al Generation of polyclonal CMV‐specific T cells for the adoptive immunotherapy of glioblastoma. J Immunother 2012; 35:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lepiller Q, Tripathy MK, Di Martino V, Kantelip B, Herbein G. Increased HCMV seroprevalence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Virol J 2011; 8:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pacsa AS, Kummerländer L, Pejtsik B, Pali K. Herpesvirus antibodies and antigens in patients with cervical anaplasia and in controls. J Natl Cancer Inst 1975; 55:775–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Taher C, de Boniface J, Mohammad A‐A, Religa P, Hartman J, Yaiw K‐C et al High prevalence of human cytomegalovirus proteins and nucleic acids in primary breast cancer and metastatic sentinel lymph nodes. PLoS One 2013; 8:e56795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Taher C, Frisk G, Fuentes S, Religa P, Costa H, Assinger A et al High prevalence of human cytomegalovirus in brain metastases of patients with primary breast and colorectal cancers. Transl Oncol 2014; 7:732–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Han XY. Epidemiologic analysis of reactivated cytomegalovirus antigenemia in patients with cancer. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:1126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schlick K, Grundbichler M, Auberger J, Kern JM, Hell M, Hohla F et al Cytomegalovirus reactivation and its clinical impact in patients with solid tumors. Infect Agent Cancer 2015; 10:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kuo CP, Wu CL, Ho HT, Chen C, Liu SI, Lu YT. Detection of cytomegalovirus reactivation in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Clin Microbiol Infect 2008; 14:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Goerig N, Semrau S, Frey B, Korn K, Fleckenstein B, Überla K et al Clinically significant CMV (re)activation during or after radiotherapy/chemotherapy of the brain. Strahlenther Onkol 2016; 192:489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wang Y‐C, Wang N‐C, Lin J‐C, Perng C‐L, Yeh K‐M, Yang Y‐S et al Risk factors and outcomes of cytomegalovirus viremia in cancer patients: a study from a medical center in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2011; 44:442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Torres HA, Kontoyiannis DP, Bodey GP, Adachi JA, Luna MA, Tarrand JJ et al Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in patients with cancer: a two decade experience in a tertiary care cancer center. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41:2268–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Chen I‐H, Lai Y‐L, Wu C‐L, Chang Y‐F, Chu C‐C, Tsai I‐F et al Immune impairment in patients with terminal cancers: influence of cancer treatments and cytomegalovirus infection. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010; 59:323–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Vudattu NK, Magalhaes I, Schmidt M, Seyfert‐Margolis V, Maeurer MJ. Reduced numbers of IL‐7 receptor (CD127) expressing immune cells and IL‐7‐signaling defects in peripheral blood from patients with breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2007; 121:1512–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Elmaagacli AH, Steckel NK, Koldehoff M, Hegerfeldt Y, Trenschel R, Ditschkowski M et al Early human cytomegalovirus replication after transplantation is associated with a decreased relapse risk: evidence for a putative virus‐versus‐leukemia effect in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Blood 2011; 118:1402–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Green ML, Leisenring WM, Xie H, Walter RB, Mielcarek M, Sandmaier BM et al CMV reactivation after allogeneic HCT and relapse risk: evidence for early protection in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013; 122:1316–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Takenaka K, Nishida T, Asano‐Mori Y, Oshima K, Ohashi K, Mori T et al Cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is associated with a reduced risk of relapse in patients with acute myeloid leukemia who survived to day 100 after transplantation: the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Transplantation‐related Complication Working Group. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21:2008–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Hilal T, Slone S, Peterson S, Bodine C, Gul Z. Cytomegalovirus reactivation is associated with a lower rate of early relapse in myeloid malignancies independent of in‐vivo T cell depletion strategy. Leuk Res 2017; 57:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Teira P, Battiwalla M, Ramanathan M, Barrett AJ, Ahn KW, Chen M et al Early cytomegalovirus reactivation remains associated with increased transplant related mortality in the current era: a CIBMTR analysis. Blood 2016; 127:2427–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Scheper W, van Dorp S, Kersting S, Pietersma F, Lindemans C, Hol S et al γδT cells elicited by CMV reactivation after allo‐SCT cross‐recognize CMV and leukemia. Leukemia 2013; 27:1328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Couzi L, Levaillant Y, Jamai A, Pitard V, Lassalle R, Martin K et al Cytomegalovirus‐induced γδ T cells associate with reduced cancer risk after kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21:181–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ranganathan P, Clark PA, Kuo JS, Salamat MS, Kalejta RF. Significant association of multiple human cytomegalovirus genomic loci with glioblastoma multiforme samples. J Virol 2012; 86:854–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Holdhoff M, Guner G, Rodriguez FJ, Hicks JL, Zheng Q, Forman MS et al Absence of cytomegalovirus in glioblastoma and other high‐grade gliomas by real‐time PCR, immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 23:3150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Baumgarten P, Michaelis M, Rothweiler F, Starzetz T, Rabenau HF, Berger A et al Human cytomegalovirus infection in tumor cells of the nervous system is not detectable with standardized pathologico‐virological diagnostics. Neuro Oncol 2014; 16:1469–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Nair SK, De Leon G, Boczkowski D, Schmittling R, Xie W, Staats J et al Recognition and killing of autologous, primary glioblastoma tumor cells by human cytomegalovirus pp65‐specific cytotoxic T cells. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20:2684–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Crough T, Beagley L, Smith C, Jones L, Walker DG, Khanna R. Ex vivo functional analysis, expansion and adoptive transfer of cytomegalovirus‐specific T‐cells in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Immunol Cell Biol 2012; 90:872–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Fornara O, Odeberg J, Wolmer Solberg N, Tammik C, Skarman P, Peredo I et al Poor survival in glioblastoma patients is associated with early signs of immunosenescence in the CD4 T‐cell compartment after surgery. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4:e1036211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Nielsen CM, White MJ, Goodier MR, Riley EM. Functional significance of CD57 expression on human NK cells and relevance to disease. Front Immunol 2013; 4:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Focosi D, Bestagno M, Burrone O, Petrini M. CD57+ T lymphocytes and functional immune deficiency. J Leukoc Biol 2010; 87:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Casazza JP, Betts MR, Price DA, Precopio ML, Ruff LE, Brenchley JM et al Acquisition of direct antiviral effector functions by CMV‐specific CD4+ T lymphocytes with cellular maturation. J Exp Med 2006; 203:2865–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Strioga M, Pasukoniene V, Characiejus D. CD8+ CD28− and CD8+ CD57+ T cells and their role in health and disease. Immunology 2011; 134:17–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Gros A, Robbins PF, Yao X, Li YF, Turcotte S, Tran E et al PD‐1 identifies the patient‐specific CD8+ tumor‐reactive repertoire infiltrating human tumors. J Clin Investig 2014; 124:2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Gros A, Parkhurst MR, Tran E, Pasetto A, Robbins PF, Ilyas S et al Prospective identification of neoantigen‐specific lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Nat Med 2016; 22:433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Schuessler A, Smith C, Beagley L, Boyle GM, Rehan S, Matthews K et al Autologous T‐cell therapy for cytomegalovirus as a consolidative treatment for recurrent glioblastoma. Can Res 2014; 74:3466–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Mitchell DA, Batich KA, Gunn MD, Huang M‐N, Sanchez‐Perez L, Nair SK et al Tetanus toxoid and CCL3 improve dendritic cell vaccines in mice and glioblastoma patients. Nature 2015; 519:366–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Reap EA, Suryadevara CM, Batich KA, Sanchez‐Perez L, Archer GE, Schmittling RJ et al Dendritic cells enhance polyfunctionality of adoptively transferred T cells that target cytomegalovirus in glioblastoma. Can Res 2018; 78:256–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Söderberg‐Nauclér C, Rahbar A, Stragliotto G. Survival in patients with glioblastoma receiving valganciclovir. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:985–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Stragliotto G, Rahbar A, Solberg NW, Lilja A, Taher C, Orrego A et al Effects of valganciclovir as an add‐on therapy in patients with cytomegalovirus‐positive glioblastoma: a randomized, double‐blind, hypothesis‐generating study. Int J Cancer 2013; 133:1204–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Peng C, Wang J, Tanksley JP, Mobley BC, Ayers GD, Moots PL et al Valganciclovir and bevacizumab for recurrent glioblastoma: a single‐institution experience. Mol Clin Oncol 2016; 4:154–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Kramm CM, Korholz D, Rainov NG, Niehues T, Fischer U, Steffens S et al Systemic activation of the immune system during ganciclovir treatment following intratumoral herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase gene transfer in an adolescent ependymoma patient. Neuropediatrics 2002; 33:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]