Abstract

Music as an effective self-regulative tool for emotions and behavioural adaptation for adolescents might enhance emotion-related skills when applied as a therapeutic school intervention. This study investigated Rap & Sing Music Therapy in a school-based programme, to support self-regulative abilities for well-being. One-hundred-and-ninety adolescents in grade 8 of a public school in the Netherlands were randomly assigned to an experimental group involving Rap & Sing Music Therapy or a control group. Both interventions were applied to six classes once a week during four months. Measurements at baseline and again after four months provided outcome data of adolescents’ psychological well-being, self-description, self-esteem and emotion regulation. Significant differences between groups on the SDQ teacher test indicated a stabilized Rap & Sing Music Therapy group, as opposed to increased problems in the control group (p = .001; ηp2 = .132). Total problem scores of all tests indicated significant improvements in the Rap & Sing Music Therapy group. The RCT results imply overall benefits of Rap & Sing Music Therapy in a school setting. There were improved effects on all measures – as they are in line with school interventions of motivational engagement in behavioural, emotional and social themes – a promising result.

Keywords: adolescents, school-based intervention, music therapy, rap & singing, emotion regulation, well-being, RCT

Being a bully isn’t very cool

If you like to bully, you will look like a fool

Stop spreading hate and instead lend a hand

This is what the world should start to understand1

The growing population of adolescents (age 10–19, WHO, n.d.) with identified emotional problems and anti-social behaviour calls for effective interventions as well as for prevention of problem behaviours (NCSE, 2015; Stockings et al., 2016; Suveg, Sood, Comer, & Kendall, 2009). In the Netherlands, 22% of adolescents (aged 8–12) have psychosocial problems: 15% experience emotional and behavioural problems, and 7% experience severe problems (Diepenmaat, Eijsden, Janssen, Loomans, & Stone, 2014). This population suffers from violence, abuse and neglect in parental and social environments, which are typical potential sources for the development of psychopathological behaviour (Dam, Nijhof, Scholte, & Veerman, 2010). Reported backgrounds for the development of psychopathological behaviour among at-risk youth reveal a high manifestation of (un-)diagnosed mental health problems and trauma (Dam et al., 2010). Studies from the United Kingdom and the United States support these findings. The Health Behaviour of School-Aged Children Survey (HBCS) has found that around 22% of English adolescents have self-harmed themselves, and that those rates have increased over the past decade, and indicate a possible rise in mental health problems among young people (HBCS, 2017). A large US study (N = 10,123) reports that one in every four or five adolescents has a mental health disorder. The prevalence of disorders is classified as follows: anxiety disorder (31.0%) represents the biggest group, followed by behaviour disorders (19.1%), mood disorders (14.3%) and substance use disorder (11.4%; Merikangas et al., 2010). Moreover, each additional type of trauma or exposure to trauma significantly increases these percentages for each problem (Layne et al., 2014). Also, a rapid rate of decline in the academic achievement of troubled mental health students (N = 300) is described in a study by Suldo, Thalji, and Ferron (2011), correlating well-being with psychopathology in middle school.

School experiences are crucial to the development of self-esteem, self-perception and health behaviour, as shown in a large study of 42 countries across Europe and North America (Inchley & Currie, 2013). Schools need to support young people’s well-being through positive engagements for better health outcomes, for example, providing buffers against negative health behaviours and outcomes (Inchley & Currie, 2013). Thus, school interventions are desired to help direct and control attention and behavioural impulses (like reacting to teasing from others) as the primary sources of difficulties related to problems with (emotional) self-regulation (Blair & Diamond, 2008; Boekaerts, Maes, & Karoly, 2005; Gestsdóttir & Lerner, 2007; Karoly, 2012; Kovacs, Joormann, & Gotlib, 2007; Raver, 2004; Vohs & Baumeister, 2011). Difficulties in emotion regulation capacities are reported by clinical studies of patients with Oppositional Defiant Disorder/Conduct Disorder, (comorbid) behavioural difficulties, childhood depression, Borderline Personality Disorder and anorexia, caused by stress, traumatic experiences and family dysfunction (Suveg et al., 2009). To support well-being, these regulative capacities are necessary for dynamic and reorganizational processes of emotional and behavioural adaptation (Blair & Diamond, 2008; Crocker, 2002; Diamond & Lee, 2011). Self-regulation is a complex process of self-directed change and serves as a “key-adaption of humans” for management of cognitive, emotional, behavioural and physiological levels (Baumeister, Schmeichel, & Voh, 2007; Karoly, 2012; Moore, 2013).

Music and Rap & Sing Music Therapy (Rap&SingMT)

Music, whatever its style, might be able to modulate some of these levels through its non-threatening sensory information (Moore, 2013), and its rewarding and emotionally evocative nature (Patel, 2011). Music induces a complex cognitive-emotional process, interacts with brain areas that modulate mood and stress (Janata & Grafton, 2003; Koelsch, 2011; Molinari, Leggio, & Thaut, 2007; Stegemann, 2013) and enhances contact, coordination and cooperation with others (Koelsch et al., 2013). Instrumental and vocal music involves multiple neural networks, and singing intensifies the activity of the right hemisphere during production of words in song in a different way from speaking (Jeffries, Fritz, & Braun, 2003), whereas regular vocalization helps to increase the connectedness between syllables and words (Wan & Schlaug, 2010). Combining instrumental music, singing and vocalizations, Rap (Rhythm And Poetry), with its rhymed couplets to an insistent beat, vocally expresses primary emotions and transforms them into words (Uhlig, 2011). Altering those primary emotions – which are spontaneously uttered – into secondary emotions, after conscious or unconscious judgment about the first (Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, & O’Connor, 1987), can result in the development of a mindful maturation process. The rationale underlying Rap&SingMT is built on those vocalizations – whether rhythmical speech in rap, or melodic lines in singing – and based on a predictable rhythmic pattern, to stabilize or modulate positive and negative emotions. This functions as a safe “bridge” between talking and singing: rhythm can structure one’s ability to synchronize to an external beat – a human capacity (Koelsch, 2015) – and might stimulate the brain by integrating and organizing sensations. Singing can involve a greater emotional component in the brain than speaking (Callan, Kawato, Parsons, & Turner, 2007; Leins, Spintge, & Thaut, 2009), which may be essential for the development of sensitivity and processes of learning. Vocal engagement, supported by rhythmic clapping, stamping, dancing or moving the body, invites participants to develop emotional, social and physical cooperation and to strengthen group cohesion (Hallam, 2010; Koelsch et al., 2013). To practise these basic skills of rapping and singing in a large group, no instruments are needed, as a transportable workstation and recording equipment are carried into the classrooms.

Clinical cases of music therapists report on the beneficial use of rap and singing interventions for self-regulation, development of coping strategies and behavioural changes for adolescents and youth (Ahmadi & Oosthuizen, 2012; Donnenwerth, 2012; Ierardi & Jenkins, 2012; Lightstone, 2012; MacDonald & Viega, 2012; McFerran, 2012; Travis, 2013; Viega, 2013, 2015). The purpose of music therapy is to stabilize, reduce or enhance individual difficulties, while engaged in the music process during the expression of personally preferred music styles, like rap, in youth (Uhlig, Dimitriadis, Hakvoort, & Scherder, 2016). This is different from the use of rap in school counselling, as it was first introduced by Elligan (Gonzalez, 2009; Travis & Deepak, 2011). Hadley and Yancy (2011) present an overview of cases of adverse experiences with difficult-to-engage adolescents and youth, and their ability for emotional transformation through rap. Even though rap music has a negative connotation for some people, destined to manipulate youth with its strong emotional expressions with strong language and violence, some might have missed rap’s cultural messages and marginalized its political critiques (Cundiff, 2013; Oden, 2015). Many rappers express non-violent but authentic messages about their grief, community distress or true feelings of loss, whereas record companies demand mostly offensive lyrics for their own profitable goals (Oware, 2011). Authors of the British “Hip Hop Psych” (2014) website, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist, have argued for further investigation on engaging in these authentic messages and linking rap music and culture with health to empower hip-hop as a prospective therapy. In the Netherlands, a music style called “Nederhop” (using the Dutch language as equivalent for spoken English hip-hop), developed as an easily understandable popular music of different ethnicities (Pennycook, 2007). Rappers of white or diverse colours perform Nederhop rap styles – not a mainstream musical culture in the Netherlands – while addressing serious, uncomfortable or humorous themes. These practices are also used in Dutch music therapy sessions as a valid tool of empowerment for youth and adults (Hakvoort, 2008, 2015). The forthcoming themes and messages will be discussed while using rap and hip-hop in therapy, nonetheless, they provide a “funky discourse” and cultural dialogue about these subjects, as Viega (2015) points out.

The present randomized controlled trial (RCT) reports on the first application of Rap&SingMT in a regular school setting in the Netherlands to support the enhancement of emotional well-being. It aims to encourage the expression of “true feelings” (Short, 2013) of adolescents within a therapeutic context, and allows music therapists early involvement in schools. It provides music therapeutic support in various educational settings, enables individual sessions after this group project, and permits ongoing engagement with teachers and parents. It aims to examine the effect of Rap&SingMT for emotion regulation by the development of self-regulative skills for modulation of positive and negative feelings, and to strengthen perception and description of the self, as well as adolescents’ self-esteem. The null hypothesis is that there will be no difference observed between the two assessed groups. Rejection of the null hypothesis would involve adolescents who participated in Rap&SingMT having a greater improvement in measures of emotional and behavioural symptoms, supporting their well-being, than those who did not take this intervention (Uhlig, Jansen, & Scherder, 2015).

Methods

Design

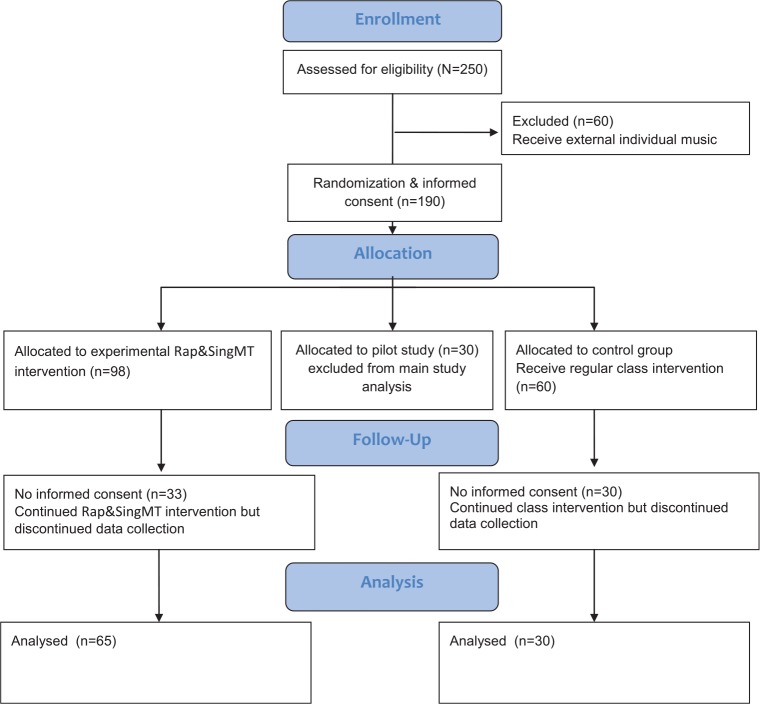

This RCT with adolescents in a public school used therapeutic rap and singing interventions as support for emotional and behavioural self-regulation to compare its effects with the control group. The Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) is applied and presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of randomized controlled trial for the Rap&SingMT study.

Participants

One-hundred-and-ninety Dutch-speaking adolescents in grade 8 were recruited at De Lanteerne, a public Jena plan school in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The Jena School system is centred around concepts of learning within a community, so that different age groups in one class engage together in dialogue, play and celebrations. Participants were boys and girls, aged between 8 and 12, partaking in the project with their own class during regular school hours. No adolescent was excluded, and no pre-screening for special needs conditions was applied. Adolescents with and without behavioural and/or developmental delays were included in the same study condition. Adolescents without parental/caregivers’ permission for data collection were not tested but participated in both group (music + control) interventions. Control groups were informed about their control status, their exclusion from music data and their postponed Rap&SingMT sessions. Six out of the eight classes participated in the Rap&SingMT, while two classes were excluded from this research because of participation in an external individual music programme. Demographic data was provided by parents, consisting of age, gender, marital status of parents and family structure, parents’ working status, parents’ education, parents’ interests and hobbies, family activities and former music education of parents and adolescents.

Randomization

All adolescents from the remaining six classes were randomly assigned for participation in the Rap&SingMT: three classes in experimental groups, two classes in control groups and one class participated in a pilot study and was therefore excluded from the main study. Pilot, experimental and control groups were selected blindly by an independent researcher at VU University Amsterdam. Qualified music therapists, a researcher and assistants were blind to information about the adolescents’ school records, behaviour problems, difficulties and diagnoses, as well as which adolescents actually partook in data collection. Music therapists worked with the adolescents in the classrooms, but did not participate in the testing. Research assistants performed testing after music and control group interventions, but without information about who participated in which group. Two teachers per classroom randomly filled in questionnaires about adolescents’ behaviour without knowing if they participated in data collection or not.

Sample size

Calculations for adequate sample sizes were based on the outcomes of the literature review, which demonstrated limited applied music intervention. Most measurements of music effects for emotion regulation purposes were based on verbal questionnaires without applied music interventions (Uhlig, Jaschke, & Scherder, 2013). This resulted in a modest sample size of N = 190 for the first study of applied music (therapeutic) interventions for emotion regulation in a school setting for adolescents (ages 8–12). So, our calculation of an effect size of Cohen’s f = 0.15 is to be considered a small effect (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). For a required 80% power threshold, the estimated sample size required per group is 45 participants, with two planned measurements. Anticipating dropout rates, the study population was targeted at 190 participants. The feasibility of a small effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.15) of the planned sample size, involving six school classes, reduced the risk of Type II errors (Banerjee, Chitnis, Jadhav, Bhawalkar, & Chaudhury, 2009).

Ethics

The study was approved by the scientific and ethical review committee of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (Vaste Commissie Wetenschap en Ethiek, VCWE: Scientific and Ethical Review Board). The head of the Jena plan school granted permission to perform Rap&SingMT during school hours. Prior to research activities, parents received information about the study and signed different informed consent forms regarding participation, and audio/video recordings of the Rap&SingMT sessions.

Materials and procedure

Standardized tests were used as a pre- and post-measure for adolescents, their parents and teachers, participating in data collection. Adolescents partaking in the Rap&SingMT without parental permission for data collection were neither tested nor interviewed. All participants of the RCT underwent two primary outcome measurements, pre- and post-intervention, respectively. The two measurements consisted of a composite of three assessments of psychological well-being (paper tests). The two assessments were administered by trained Master’s students in Clinical Neuropsychology of the VU University Amsterdam, and took about 30–40 minutes, depending on the participant. The researchers guided and monitored adolescents during the two periods of group data collection at school over the course of six months.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Psychological well-being was assessed by measures of self-description: Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire (SDQ), function of emotion regulation: Difficulties Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and evaluation of Self-esteem: Self-Perception Profile Children (SPPC).

Secondary outcomes

A qualitative inquiry investigated about “how’’ music affected adolescents, and their emotional reality as `lived music experience’, by performing interviews.

Self-description: Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire (SDQ)

The SDQ identifies a young person’s risk for psychiatric disorders (ages 4–16 years), and describes the person’s strengths and difficulties. Three different SDQ versions, the self-report of the adolescent and the informant-rated version, completed, respectively, by a parent and a teacher, provided information about health for the purpose of anticipation and prevention (Muris, Meesters, Eijkelenboom, & Vincken, 2004). The teacher version of the SDQ had been tested in Dutch schools as a valid instrument with satisfactory and good internal consistency, and as an indicator of emotional and social problems (Diepenmaat et al., 2014). SDQ is a 25-item questionnaire, assessing psychosocial traits on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, to 2 = certainly true. The items lead to five scores on the following scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviour. A “total problem score” is created, ranging from 0 to 40, by summing 20 item scores of the four problem scales, without the prosocial item. A defined cut-off score higher than 14 for “total problem score” rated by teachers indicated an adolescent being at heightened risk for developing mental health problems. In this study, defined Dutch cut-off scores for genders were used (14 for boys and 12 for girls), as well as “borderline” states (10 for boys and 8 for girls) as described by Diepenmaat et al. (2014).

Emotion regulation: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)

The DERS evaluates the functionality of emotion regulation at different ages (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Neumann, van Lier, Gratz, & Koot, 2009; Weinberg & Klonsky, 2009). DERS is recommended as a useful emotion regulation (ER) scale for youth, emphasizing negative emotions. Its scores and subscales are associated with behavioural, neurological and experimental measures (Neumann et al., 2009). In this study, DERS was applied for adolescents (aged 8–12) in the Dutch translation of 32 items. DERS has a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 5.3, so an average fifth-grader should be able to understand and fill in the questionnaire (Neumann et al., 2009). DERS internal consistency within (non)clinical populations has been found to be comparable between adults and adolescents as well as having convergent and predictive validity (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Neumann et al., 2009). The six scales of the Dutch DERS self-report questionnaire (32 items) are as follows: lack of emotional awareness, lack of emotional clarity, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviours when distressed, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour when distressed, non-acceptance of negative emotional responses, and limited access to effective ER strategies. Each item was scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher scores suggest higher problems in emotion regulation, and a “total problem score” aggregates the six scales.

Self-esteem: Self-perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Dutch version CBSK: Competentie Belevingsschaal voor kinderen)

SPPC for children and adolescents (aged 8–12 years) measures self-esteem to indicate their own self-perception (Treffers et al., 2004). Analyses about correlation between self-esteem and depression, anxiety and externalizing problems, suggest that measures of increased self-esteem reduced these vulnerabilities (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005; Sowislo & Orth, 2013). The reliability of the SPPC is satisfactory with good internal consistency and test–retest stability and obtained validity for self-esteem (Muris, Meesters, & Fijen, 2003). The Dutch CBSK version of SPPC was translated and evaluated for Dutch samples by Veerman (1989). SPPC consists of 36 items distributed across six scales with five domain-specific subscales: scholastic competence, social acceptance, athletic competence, physical appearance, behavioural conduct and one global measure of self-worth. Each scale measured six items and consisted of two opposite (left/right) descriptions. The adolescents chose the best fitting answer for themselves and marked that with “really true” or “sort of true”. Responses represent low perceived competence scores of 1 or 2, and high scores of 3 or 4. For each of the self-esteem domains and the global self-worth scale, a total score is computed by summing relevant items (Muris et al., 2003).

Intervention

The RCT study employed an estimated 16 sessions of 45 minutes per week, over a period of four months. The Rap&SingMT intervention and the regular activities for the control group were designed for large groups of 30 adolescents per class. Ninety-eight adolescents, divided into three classes, underwent Rap&SingMT, and 60 adolescents, divided into two classes received regular classes. The Rap&SingMT group received music instructions by trained music therapists and control groups received instruction by regular classroom teachers, both during 45 minutes per week of school time. The Rap&SingMT was applied by two music therapists, working together during eight weeks in one class. After this the classes were split into subgroups of 2 × 15 adolescents, and each group continued with one therapist for the next eight weeks. In Rap&SingMT participants worked on specific group and individual themes, and prepared for audio and video recordings of individual and group rap-songs. Regular class interventions were performed “as intervention as usual” by two classroom teachers. Teachers worked on self-decided school themes and goals with students (subjects varied strongly, e.g. language, mathematics, physical activity, art) within multiage sub-groups. The qualified music therapists were trained prior to performance of the Rap&Sing MT, and underwent supervision and evaluation sessions provided by the first author during the entire research. The classroom teachers participated in regular team meetings at the Jena plan school. Music therapists, researchers and assistants were involved in school team meetings only during organizational arrangements with teachers and school management, in which the development of the adolescents was not discussed.

Rap&SingMusicTherapy protocol

The Rap&SingMT protocol was applied to stimulate regulative emotional processing, as it is constructed around components of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which involve feelings, thoughts, behaviours and physiology, and elements of psycho-education. Rap&SingMT employed a therapeutic structure, facilitated the overall expression of “true” feelings (Short, 2013) and offered a route for the modulation of emotions, especially negative ones (e.g. anxiety, sadness and anger), as these are often difficult to inflect (Suveg et al., 2009). Rap&SingMT is based on three elements of music: (1) rhythm, (2) vocal expression of singing and rapping, and (3) development of word rhyme for song lyrics (Uhlig et al., 2015). These elements were applied:

Effective rhythmic engagement to synchronize emotional expression to an external beat, and (to) affect sensory coordination (Koelsch, 2015; Thaut, 2013), (to promote) group cohesion and cooperation (Phillips-Silver, Aktipis, & Bryant, 2010). To induce the rhythmic patterns, programmed loops and body-percussion were used to combine visual and physical expressions and to encourage synchronization processes (physiology). By repeating the rhythmic patterns, adjusting tempi and dynamics, predictability was enhanced to facilitate a grounding pattern for group stability.

Singing and rapping were used as pleasurable activities, to involve a greater emotional engagement of the brain (Callan, Tsytsarev, Hanakawa, & Callan, 2006) and to induce mood changes (feelings). Rapping, singing and repeating vocal sounds of the group encouraged development of dialogues and contained feelings.

Vocalizations, linking syllables and words, chunked into rhyme and lyrics, encouraged learning through songs (Leins et al., 2009). To enhance self-esteem by accepting (negative and positive) lyrics, problem-solving skills were behaviourally trained and destructive feelings modulated or reduced. A large number of downloaded samples and loops with different rap-song styles (e.g. aggressive, easygoing or lyrical) were offered and discussed as an invitation for improvisation and self-experiment. Individual lyric/poem writing was stimulated by applying a fill-in-the-blank technique, and motivated word recall and further reflection about therapy relevance (thoughts). Rap&SingMT interventions were applied to increase the individual awareness of emotional states and behaviours, and to stimulate empathy and decision making within the group. For transfer of group experiences, video recordings were made to share rap songs with outsiders (peers, parents and teachers). An emotional and social encounter was created for reappraisal of emotion regulation strategies by reflectively discussing the recordings in the classroom.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 23 (IBM Corporation 2015), and level of significance was set at p < .05. Analysis was based on intention to treat (ITT) to preserve the sample size and to minimize missing outcome data (Gupta, 2011). The chosen paper tests offered a controlled test environment, and provided a technical error-free condition and minimalized missing values. Due to the pleasurable nature of the music activities, dropout rates and missing data could be limited. A non-parametric test was used to compare Rap&SingMT and control groups (Mann-Whitney U test). Differences between participants in school, classes, parental conditions, ages and sexes were considered as within–between interaction variables. To define whether a change has occurred in an adolescent’s emotional and behavioural functioning, several items were compared with baseline and later test moments. Differences between the Rap&SingMT and control groups in the two measurements were analysed with a repeated-measures ANOVA. General linear model (GLM) multivariate ANOVAs were used for analysis of pre- and post-intervention scores and conditions. One-way ANOVA was used to collect test summaries and subscales as within-subjects variables to compare with the between-subjects factor. Time functioned as an independent variable and represented the measurement for Rap&SingMT (pre/post). To minimize uncontrolled covariates whose effects may be confounded with the intervention effect (Porta, Bonet, & Cobo, 2007), ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) was applied as an extension of the employed one-way ANOVA, and to determine whether there were significant differences between the means of two or more independent (unrelated) groups. Univariate analyses compared dependent variables of post- with pre-measures as covariates, whereby fixed factors were used to analyse both groups. Significant group interactions were further explored with pairwise group comparisons to locate group differences. The main effect measures of time and interactions between groups are reported as mean differences of 95% confidence interval. Partial eta-squared (ηp2) was used to estimate small (.010), medium (.060) and large (.140) effects (Cohen, 1988). Pearson correlations were calculated between the different demographic variables and baseline SDQ teacher total scores. The outcome measures investigated whether there were correlations with demographic and family circumstances for each adolescent and between groups (Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003; Rescorla et al., 2007). Also, to test if correlations coefficients contrasted between groups, z-scores and paired samples t-tests were applied to compare the scores of both, as described in Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2013).

Results

Demographics

No significant differences were found between the Rap&SingMT and control group on conditions of age, gender, family conditions, parents’ education, music education parents/adolescents and percentage of adolescents with or without problems (applied SDQ teacher tests), as presented in Table 1. Also, a Mann-Whitney U test demonstrated equal group conditions, whereas the different Z-scores indicate dissimilarity between pre- (Z = -0.53) and post-measures (Z = 2.227). No significant difference between group conditions (SDQ teacher test) was found in pre-measures (U = 968, p = .958). Treatment effects were therefore not dependent on their pre-measures.

Table 1.

Group characteristic demographics of Rap&SingMT and Control group (t-test).

| Demographic baseline data | Rap&SingMT group n = 65 |

Control group n = 30 |

Between group difference |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | F | P | |

| Age (8–13 years) | 10.17 | 1.24 | 10.37 | 0.76 | 12.35 | n.s. |

| Gender (40 boys/55 girls) | 1.52 | 0.50 | 1.70 | 0.46 | 11.40 | n.s. |

| Family conditions home (single/married/kids) | 2.69 | 0.73 | 2.47 | 0.73 | 0.52 | n.s. |

| Education parents (elementary/college/higher education) | 3.66 | 0.76 | 3.50 | 0.77 | 1.06 | n.s. |

| Music education parents (years/instruments) | 3.95 | 4.87 | 4.18 | 6.25 | 0.79 | n.s. |

| Music education adolescents (years/instruments) | 1.02 | 1.28 | 0.85 | 1.09 | 0.12 | n.s. |

| Problems SDQ score teacher pre-test | 4.06 | 4.29 | 4.17 | 4.60 | 0.00 | n.s. |

Intervention

Between subjects

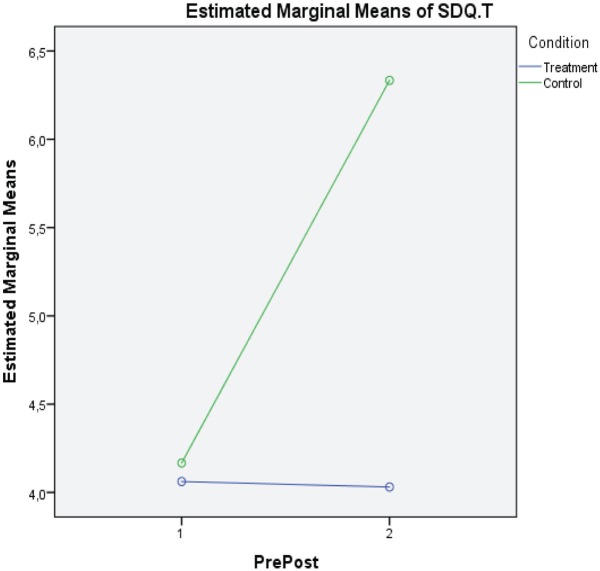

In Table 2, results of the SDQ teacher test (SDQ T Total) showed a significant difference between groups (p = .001). The mean scores indicate that the Rap&SingMT group score did not change over time whereas in the control group mean scores of problems increased. Two of the four problem scales, emotional symptoms (E) and hyperactivity/inattention (H) presented significant scores in groups between pre-and post-intervention measures as well as large and moderate effect sizes (E: p = .001, ηp2 = .107; H: p = .01, ηp2 = .069), favouring the Rap&SingMT group (See Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Effects of assessments on psychological well-being: Test total scores of pre- and post-measures (ANOVA).

| Tests total scores | Rap&SingMT group n = 65 |

Control group n = 30 |

Within–between group differences |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

F | df | p | ηp2 | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| SDQ T Total | 4.06 | 4.29 | 4.03 | 4.25 | 4.17 | 4.60 | 6.33 | 5.06 | 14.13 | 1 | .001 | .132 |

| SDQ P Total | 6.82 | 5.71 | 5.69 | 4.59 | 6.43 | 4.35 | 6.20 | 4.14 | .34 | 1 | .137 | .024 |

| SDQ K Total | 10.89 | 6.14 | 9.34 | 5.41 | 11.50 | 5.62 | 9.23 | 4.89 | <.01 | 1 | .963 | <.001 |

| DERS K Total | 74.22 | 27.46 | 67.08 | 22.46 | 68.73 | 18.04 | 66.57 | 18.21 | 1.38 | 1 | .243 | .015 |

| SPPC K Total* | 107.46 | 16.38 | 109.93 | 14.64 | 110.46 | 11.52 | 111.26 | 11.78 | .12 | 1 | .726 | .001 |

Note. *Increase = positive improvement. SDQ: Strength Difficulty Questionnaire (T = teacher, P = parents, K = kids = children); DERS: Difficulty Emotion Regulation (children); SPPC: Self-Perception Profile Children and self-esteem (children).

Table 3.

Effect on subscales Strength Difficulty Questionnaire (SDQ teacher): Test total scores of pre- and post-measures (ANOVA).

| Tests Subscales SDQ |

Rap&SingMT Experimental group n = 65 |

Control group n = 30 |

Within–between group differences |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDQ T = Teacher | Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

F | df | p | ηp2 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| SDQ TE | 1.06 | 1.68 | 0.91 | 1.51 | 0.87 | 1.30 | 1.60 | 1.87 | 11.18 | 1 | .001 | .107 |

| SDQ TC | 0.26 | 0.87 | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 1 | .391 | .008 |

| SDQ TH | 2.25 | 2.59 | 2.42 | 2.77 | 2.30 | 2.42 | 3.43 | 3.11 | 12.52 | 1 | .010 | .069 |

| SDQ TPP | 0.49 | 1.03 | 0.49 | 1.03 | 0.83 | 1.66 | 1.07 | 1.48 | 1.34 | 1 | .249 | .014 |

| SDQ TPS* | 9.02 | 1.57 | 9.18 | 1.33 | 9.03 | 1.65 | 9.27 | 1.11 | 0.06 | 1 | .796 | .001 |

Note. *Increase = positive improvement. SDQ: Strength Difficulty Questionnaire; T: teacher; E: Emotional symptoms, C: Conduct problems, H: Hyperactivity/inattention, PP: Peer relationship problems, PS: Pro-Social behaviour.

Figure 2.

Pre- and post-intervention measures of SDQ Teacher problem scores for the treatment and control groups.

The SDQ-Parents measure (SDQ P Total) showed a non-significant but greater permanence of problems in the control group. The SDQ-Children (SDQ K Total) results were not significant. Further, the total scores for DERS yielded greater permanence of problems in emotion regulation within the control condition, with a significant difference on the subscale “difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviour when distressed” (p = .025) with a moderate effect size of ηp2 = .053 in favour of the Rap&SingMT intervention. Total scores of SPPC for self-perception were not significant, only subscale “Global Self-worth” revealed a moderate increased effect size (ηp2 = .031) for the Rap&SingMT group. Inspection of univariate tests with Bonferroni adjustment (α = .005) revealed no individual dependent variables that significantly contributed to the interaction in the model (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect on subscales Difficulty Emotion Regulation (DERS): Test total scores of pre- and post-measures (ANOVA).

| Tests Subscales DERS | Rap&SingMT Experimental group n = 65 |

Control group n = 30 |

Within–between group differences |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

F | df | p | ηp2 | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| DERS EA | 15.88 | 5.70 | 15.77 | 5.68 | 16.13 | 4.71 | 16.40 | 4.29 | .15 | 1 | .698 | .002 |

| DERS EC | 9.74 | 4.91 | 9.32 | 4.16 | 9.60 | 3.67 | 9.10 | 3.69 | 0.01 | 1 | .923 | <.001 |

| DERS IC | 11.22 | 6.32 | 9.88 | 5.15 | 8.87 | 3.56 | 8.93 | 4.33 | 1.54 | 1 | .218 | .016 |

| DERS GB | 11.69 | 5.69 | 9.69 | 5.07 | 10.47 | 4.50 | 10.90 | 4.22 | 5.16 | 1 | .025 | .053 |

| DERS ER | 11.32 | 5.88 | 10.03 | 4.76 | 10.40 | 5.75 | 8.93 | 4.53 | 0.28 | 1 | .867 | <.001 |

| DERS ES | 14.37 | 8.05 | 12.38 | 6.08 | 13.27 | 6.61 | 12.30 | 5.33 | 0.46 | 1 | .499 | .005 |

Note. EA = Lack of Emotional Awareness; EC = Lack of Emotional Clarity; IC = Difficulty Controlling Impulse Behaviour when Distressed; GB = Difficulties Engaging in Goal-Directed Behaviour when Distressed; ER = Non-acceptance of Negative Response; ES = Limited Access to Effective ER Strategies.

Within subjects

In Table 5, also analysed data within each group separately. Results of assessed problem scores (SDQ T, SDQ P, SDQ K, DERS) were summed into one total “problem” score. Within the subjects of the Rap&SingMT group, a paired samples t-test showed that the problem scores declined significantly from pre-treatment (M = 95.99, SD = 38.04) to post-treatment (M = 86.14, SD = 30.63, t(64) = 3.14, p <.004). Within the subjects of the control group the decline in scores from pre-treatment (M = 90.83, SD = 26.02) to post-treatment (M = 88.33, SD = 25.24) was not significant, t(29) = .77, p < .45.

Table 5.

Total problem scores of all tests, comparing groups (t-test).

| Rap&SingMT Experimental group n = 65 |

t-test | Control group n = 30 |

t-test | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | |

| Total problem tests | 95.99 | 38.04 | 86.14 | 30.63 | 3.14 | 64 | .004 | 90.83 | 26.02 | 88.33 | 25.24 | .77 | 29 | .45 |

Interviews

The subjective experiences of adolescents yielded narrative data, collected by interviews and analyzed in a qualitative coding system of ATLAS.ti (not presented here). The results show, that the main experience of the adolescents about Rap&SingMT was positive - they generally interpreted it as an ‘outlet’, and learned to be more “engaged in their emotions’’, developed “self-knowledge”, “voiced their emotions into words”, and “were free to speak out”.

Discussion

Our study aimed to examine whether Rap&SingMT had a beneficial influence on adolescents, in support of their well-being, and successfully rejected the null hypothesis. The purpose of Rap&SingMT was to strengthen self-perception and self-description as well as self-esteem by the development of self-regulative skills for modulation of positive and negative feelings. We compared the effects of Rap&SingMT with a school “intervention as usual” and found significant increases in the level of problems of the control group on SDQ total Teacher score, on subscales for “emotional symptoms”, “hyperactivity/inattention”, and on the DERS subscale of “difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviour when distressed”. The total problem scores of SDQ Parents, SDQ Children and the self-esteem scores of SPPC did not show significant changes. Finally, the total “problem” score of all tests showed a significant decline in the Rap&SingMT group during the treatment period whereas during the same period the control group remained level.

Nevertheless, all the test results revealed increased problems and decreased measures of self-esteem in the control group, as judged by the differences in the medians of the two groups. In contrast, we did not find the same negative changes in the Rap&SingMT intervention group. This is in line with other school interventions for motivational, behavioural, emotional and social engagement. These studies also observed stabilization of behaviours and limited problems, even when completed by children with psychiatric patterns (Breeman et al., 2015) or unmotivated adolescents (Lambie, 2004). In terms of the presence/absence of psychiatric or psychosocial problems, the effect of engaging interventions on stabilizing behaviour and limited problems was similar in those studies. Rap&SingMT results look promising for several (non)problematic behaviours, and a possible explanation for this finding might be the engagement in behavioural, emotional and social themes, like addressing the “true” feelings of adolescents. Further, in the analysis we differentiated for effects on psychosocial problems of adolescents (SDQ teacher score as indicator for problems), but the participant group yielded 6% fewer problems than the Dutch average (eight adolescents in each group). Therefore, the requirements for statistical power were not met and this analysis was not pursued further. Consequently, the defined problem score of the Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire of teachers was powerless as a group measure for our school, and our study pertained to heterogeneous groups of adolescents, defined as “with and without problems” as usual in schools.

Moreover, assessing adolescents at the end of the school year, especially just before the vacation can mean students of all ages and capacities are typically progressively restless and distracted in their behaviours (Oliver & Reschly, 2007). High levels of misconduct of students and time pressure for teachers before and after vacation are positively related to an increase of emotional exhaustion in both (Kühnel & Sonnentag, 2011). School interventions for motivational engagement, like Rap&SingMT, seem particularly appropriate as pleasurable, nourishing and evocative activities at this time of the year, even with challenging themes and discourses. On the other hand, performing the paper assessments after this music intervention, starting in February and finalizing them just before vacation in July, was likely associated with exhaustion. Correlations with well-being in schools show a decline in academic achievement with troubled mental health for all students (Suldo et al., 2011). Therefore, a small improvement of emotional and hyperactive symptoms during distress, such as that achieved in this study, might stabilize these vulnerabilities. Also, Rap&SingMT used cognitive restructuring strategies and involvement in positive and negative feelings and thoughts, and might have improved problem-solving skills (Aldao, 2013; Blair & Diamond, 2008; Sowislo & Orth, 2013; Stockings et al., 2016). Intervention programs that use CBT in school are effective in preventing internalizing disorders, like depression and anxiety (Stockings et al., 2016). Rap&SingMT interventions aimed to modulate (negative) emotions of adolescents due to, for example, unstable peer relationships (Zimmermann & Iwanski, 2014) and succeeded by engagement in goal-directed behaviour. Participants freely expressed their feelings about vulnerable subjects in raps and lyrics, such as bullying or the desire for friendship, and were encouraged – not treated as having individual problem behaviour, but supported in this complex route of self-regulation in school (see an example of rap lyrics at the start of the article).

Furthermore, teacher total scores (SDQ) were significant, they were able to observe all students: in Rap&SingMT as well as in control group sessions, including adolescents without permission for data collection. Teachers were curious to witness the musical experiences of their pupils, similar to the interest in the control group’s performance during their self-applied intervention. Parents did not witness this process; they filled in tests, and later received a summary of sessions on DVD after Rap&SingMT was completed. The observed differences between measurements of parents and teachers might have been influenced by their different observer-roles, as the latter were present during both the Rap&SingMT and control group sessions, and the former were not. Further, adolescents were strongly motivated and involved in the Rap&SingMT, but disliked filling in the questionnaires and argued that the questions were “not connected to the music”. By sensing this, and not being able to translate their personal music experience into a verbal questionnaire, those missing measures about their true feelings after Rap&SingMT might have biased our results. Also, non-significant results of SPPC total scores might reflect a lack of correlation between musical experience and scales of “scholastic and athletic competences and appearances”. Consequently, individual changes or anticipation patterns about emotion regulation subjects of the adolescents were possibly partially due to the negative responses of adolescents to verbal tests. This poses a challenge for the interpretation of (non)significant Rap&SingMT effects of single tests versus an interesting visible tendency on the significant test summary. Test scores yielded small, medium or large effects of Rap&SingMT interventions; thus careful interpretations about these pre- and post-intervention measures are required. Further, correlational analysis failed to show statistically significant relations and insights between groups, times and demographics. No further conclusions about age, gender, family condition or indicated level of problems (SDQ teacher score) can be drawn about adolescents’ emotional and behavioural functioning, and both groups appear heterogeneous.

Limitations

This study evaluated the applied Rap&SingMT on short-term effects of self-regulative ability of adolescents during a period of four months. To our knowledge, it is the first study on the underrepresented subject of music and emotion regulation in a school group setting, and we tested its application. There were no other studies to compare with, nor existing validated measurements for music and emotion assessment. For long-term emotional and behavioural adaptation processes, interventions and assessments might need to cover longer periods of time, and to repeat interventions for at least 9 or 12 months, to specifically reduce internalizing problems (Stockings et al., 2016). The short Rap&SingMT cycles of 45 minutes once a week during four months interfered with school schedules, which limited the number of sessions from 16 to 13. This might have resulted in a lack of effects for adolescents as well as for parents being aware of adolescents’ emotion-related behaviour. Further concerns about collected data, from subjective experiences and reflections by Rap&SingMT participants, revealed that adolescents were unable or unwilling to translate their “lived music experiences” into words. Musical emotions seem not to be directly translatable into words (Aljanaki, Wiering, & Veltkamp, 2016; Schellenberg, 2011), an often-discussed theme, and this is especially true for pre-verbal experiences during “flow” moments in music. Also, those concerns deeply explored the missing links (Hesse-Biber, 2012) between the experiences of adolescents and the results from the interviews as ‘pleasurable music activities’, their ‘learning processes’ and filling in ‘text-based problem-questionnaires’. Thus, based on our results, we challenge the suitability of these verbal questionnaires as qualitative adequate assessments of applied music interventions (Schellenberg, 2011) in relation to emotion regulation processes (Aldao, 2013; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Additionally, involvements in music styles, like rap and hip-hop, incorporate important personal, cultural and political messages – which need to be sincerely debated, also in music therapy (Cundiff, 2013; Oden, 2015; Uhlig et al., 2016; Viega, 2015). Our study underrepresented those subjects because of its primary pleasurable, nourishing and evocative character as a school activity, where those themes did not appear within our “white” population during this short intervention time. Further, in order to minimize confirmation bias in this study, the principal researcher continually attempted to re-evaluate all beliefs and impressions: not becoming involved in performance of Rap&SingMT session or testing; not participating in class-, teacher- or school-meetings during the study, except for planning issues; not pre-judging the responses that could confirm the hypothesis; not reviewing any data during the Rap&SingMT performance prior to analysis; and not using respondents’ information to confirm impressions about the adolescents. Although those precautions were applied, some evidence could have been dismissed that supported our hypothesis by the natural tendency or shortcoming of not being able to filter all information.

Conclusion

We compared the effect of Rap&SingMT on emotion regulation to a control condition, whereby Rap&SingMT yielded significant improvements on measures of emotional symptoms and hyperactivity/inattention items (SDQ T), and on the DERS subscale of “difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviour when distressed”. No other applied measures showed significant outcomes. However, there seems to be an overall benefit of Rap&SingMT, indicated by its significantly declined problem score of all measures, as opposed to the control group – a promising result. Our findings point to links with studies for emotional and motivational engagement, as Rap&SingMT provided group collaboration by identifying sensitive personal and peer themes in a safe music therapeutic environment, to enhance skills for well-being in adolescence.

Example of a personal expression of adolescents’ concern, worrying about bullying, by voicing his wishes for the world around him. His transformed feelings and thoughts were woven into rap lyrics during the performed Rap & Sing Music Therapy of this study (translation from Dutch: Pesten is niet leuk. Pesten moet je kappen. Dat is wat de hele wereld moet snappen!).

Footnotes

Ethical approval: VCWE registration number 2500: this approval was sufficient, no CCMO (Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects) or Medical Ethical Committee registration was required, permitting this research in a non-clinical school setting.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahmadi M., Oosthuizen H. (2012). Naming my story and claiming my self. In Hadley S., Yancy G. (Eds.), Therapeutic uses of rap and hip hop (pp. 191–211). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A. (2013). The future of emotion regulation research capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(2), 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aljanaki A., Wiering F., Veltkamp R. C. (2016). Studying emotion induced by music through a crowdsourcing game. Information Processing & Management, 52(1), 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Chitnis U. B., Jadhav S. L., Bhawalkar J. S., Chaudhury S. (2009). Hypothesis testing, type I and type II errors. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 18(2), 127–131. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.62274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R., Schmeichel B., Voh K. (2007). Self-regulation and the executive function: The self as controlling agent. In Kruglanski A. W., Higgins E. T. (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2nd ed., pp. 516–539). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C., Diamond A. (2008). Biological processes in prevention and intervention: The promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology, 20(3), 899–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekaerts M., Maes S., Karoly P. (2005). Self-regulation across domains of applied psychology: Is there an emerging consensus? Applied Psychology, 54(2), 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Breeman L. D., van Lier P. A., Wubbels T., Verhulst F. C., van der Ende J., Maras A., … Tick N. T. (2015). Effects of the Good Behavior Game on the behavioral, emotional, and social problems of children with psychiatric disorders in special education settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(3), 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Callan D. E., Kawato M., Parsons L., Turner R. (2007). Song and speech: The role of the cerebellum. The Cerebellum, 6, 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callan D. E., Tsytsarev V., Hanakawa T., Callan M. (2006). Song and speech: Brain regions involved with perception and covert production. NeuroImage, 31(3), 1327–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Cohen P., West S., Aiken L. (2013). Applied multiple regression and correlation analysis for behavioural science (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J. (2002). Contingencies of self-worth: Implications for self-regulation and psychological vulnerability. Self and Identity, 1, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cundiff G. (2013). The influence of rap and hip-hop music: An analysis on audience perceptions of misogynistic lyrics. Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 4(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dam C. V., Nijhof K., Scholte R., Veerman W. (2010). Evaluatie Nieuw Zorgaanbod Gesloten jeugdzorg voor jongeren met ernstige gedragsproblemen: Eindrapport [Evaluation of New Healthcare in closed youthcare with adolescents with severe behavioral problems: Final report]. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Practicon en Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A., Lee K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science, 333(6045), 959–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diepenmaat A., van Eijsden M., Janssens J., Loomans E., Stone L. (2014). Verantwoording SDQ leerkrachtvragenlijst voor gebruik binnen het onderwijs en in de zorg. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: GGD Amsterdam/Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan M. B., Trzesniewski K. H., Robins R. W., Moffitt T. E., Caspi A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16(4), 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnenwerth A. M. (2012). Song communication using rap music in a group setting with at-risk youth. In Hadley S., Yancy G. (Eds.), Therapeutic uses of rap and hip hop (pp. 275–290). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Lang A. G., Buchner A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestsdóttir S., Lerner R. M. (2007). Intentional self-regulation and positive youth development in early adolescence: Findings from the 4-h study of positive youth development. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 508–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez T. (2009). Rap Music in school counseling based on Don Elligan’s rap therapy. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 4(2), 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K. L., Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. K. (2011). Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 2(3), 109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley S., Yancy G. (Eds.). (2011). Therapeutic uses of rap and hip hop. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hakvoort L. (2008). Rapmuziektherapie, een muzikale methodiek [Rap music therapy, a musical approach]. In Tijdschrift voor Vaktherapie, 4(4), 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hakvoort L. (2015). Rap music therapy in forensic psychiatry: Emphasis on the musical approach to rap. Music Therapy Perspectives, 33(2): 184–192. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miv003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam S. (2010). The power of music: Its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of children and young people. International Journal of Music Education, 28(3), 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- HBCS. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/621068/Health_behaviour_in_school_age_children_self-harm.pdf

- Hesse-Biber S. (2012). Weaving a multimethodology and mixed methods praxis into randomized control trials to enhance credibility. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(10), 876–889. [Google Scholar]

- Hip Hop Psych. (2014). Our vision: What is hip hop psych? Retrieved from http://www.hiphoppsych.co.uk/index.html

- Ierardi F., Jenkins N. (2012). Rap composition and improvisation in a short-term juvenile detention facility. In Hadley S., Yancy G. (Eds.), Therapeutic uses of rap and hip hop (pp. 253–273). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Inchley J., Currie D. (2013). Growing up unequal: Gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and well-being (Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2013–2014 survey). Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Janata P., Grafton S. (2003) Swinging in the brain: Shared neural substrates for behaviors related to sequencing and music. Nature Neuroscience, 6(7), 682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries K. J., Fritz J. B., Braun A. R. (2003). Words in melody: An H215O PET study of brain activation during singing and speaking. Neuroreport, 14(5), 749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoly P. (2012). Self-regulation. In O’Donohue W., Fisher J. E. (Eds.), Cognitive behavior therapy: Core principles for practice (pp. 183–213). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S. (2011). Toward a neural basis of music perception: A review and updated model. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 110. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S. (2015). Music-evoked emotions: Principles, brain correlates, and implications for therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1337(1), 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S., Skouras S., Fritz T., Herrera P., Bonhage C., Küssner M. B., Jacobs A. M. (2013). The roles of superficial amygdala and auditory cortex in music-evoked fear and joy. NeuroImage, 81, 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M., Joormann J., Gotlib I. H. (2008). Emotion (dys)regulation and links to depressive disorders. Child Development Perspectives, 2(3), 149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühnel J., Sonnentag S. (2011). How long do you benefit from vacation? A closer look at the fade-out of vacation effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(1), 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lambie G. W. (2004). Motivational enhancement therapy: A tool for professional school counselors working with adolescents. Professional School Counseling, 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Layne C. M., Greeson J. K., Ostrowski S. A., Kim S., Reading S., Vivrette R. L., … Pynoos R. S. (2014). Cumulative trauma exposure and high risk behavior in adolescence: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(S1), S40. [Google Scholar]

- Leins A., Spintge R., Thaut M. (2009). Music therapy in medical and neurological rehabilitation settings. In Hallam S., Cross I., Thaut M. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music psychology (pp. 526–535). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lightstone A. (2012). Yo, can ya flow! Research findings on hip-hop aesthetics and rap therapy in an urban youth shelter. In Hadley S., Yancy G. (Eds.), Therapeutic uses of rap and hip hop (pp. 211–251). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald S., Viega M. (2012). Hear our voices: A music therapy songwriting program and the message of the little saints through the medium of rap. In Hadley S., Yancy G. (Eds.). (2012). Therapeutic uses of rap and hip hop (pp. 153–171). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McFerran K. (2012). Just so you know, I miss you so much: The expression of life and loss in the raps of two adolescents in music therapy. In Hadley S., Yancy G. (Eds.). (2012). Therapeutic uses of rap and hip hop (pp. 173–189). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., He J. P., Burstein M., Swanson S. A., Avenevoli S., Cui L., … Swendsen J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari M., Leggio M., Thaut M. (2007). The cerebellum and neural networks for rhythmic sensorimotor synchronization in the human brain. The Cerebellum, 6, 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. S. (2013). A systematic review on the neural effects of music on emotion regulation: Implications for music therapy practice. Journal of Music Therapy, 50(3), 198–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Meesters C., Eijkelenboom A., Vincken M. (2004). The self-report version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: Its psychometric properties in 8-to 13-year-old non-clinical children. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(4), 437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Meesters C., Fijen P. (2003). The self-perception profile for children: Further evidence for its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(8), 1791–1802. [Google Scholar]

- NCSE (2015). Serving at-risk youth. Retrieved from http://schoolengagement.org/school-engagement-services/at-risk-youth

- Neumann A., van Lier P. A., Gratz K. L., Koot H. M. (2009). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents using the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Assessment, 17(1), 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oden L. M. (2015). “The strength of street knowledge”: Media representations of the political discourse of gangsta rap. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/rbc/2015conference/panel8/2/

- Oliver R. M., Reschly D. J. (2007). Effective classroom management: Teacher preparation and professional development (TQ Connection Issue Paper). Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality; Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED543769.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Oware M. (2011). Brotherly love: Homosociality and black masculinity in gangsta rap music. Journal of African American Studies, 15(1), 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Patel A. D. (2011). Why would musical training benefit the neural encoding of speech? The OPERA hypothesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 142. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook A. (2007). Language, localization, and the real: Hip-hop and the global spread of authenticity. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 6(2), 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Silver J., Aktipis C. A., Bryant G. A. (2010). The ecology of entrainment: Foundations of coordinated rhythmic movement. Music Perception, 28(1), 3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta N., Bonet C., Cobo E. (2007). Discordance between reported intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(7), 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver C. C. (2004). Placing emotional self-regulation in sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts. Child Development, 75(2), 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L., Achenbach T., Ivanova M. Y., Dumenci L., Almqvist F., Bilenberg N., … Verhulst F. (2007). Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents of children ages 6 to 16 in 31 societies. Journal of Emotional and behavioral Disorders, 15(3), 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg E. G. (2011). Music lessons, emotional intelligence, and IQ. Music Perception, 29(2), 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Short H. (2013). Say what you say (Eminem): Managing verbal boundaries when using rap in music therapy, a qualitative study. Voices, 13(1). Retrieved from https://voices.no/index.php/voices/rt/printerFriendly/668/598 [Google Scholar]

- Silk J. S., Steinberg L., Morris A. S. (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development, 74(6), 1869–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowislo J. F., Orth U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegemann T. (2013). Stress, Entspannung und Musik – Untersuchungen zu rezeptiver Musiktherapie im Kindes- und Jugendalter (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Institut für Musiktherapie Hochschule für Musik und Theather, Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Stockings E. A., Degenhardt L., Dobbins T., Lee Y. Y., Erskine H. E., Whiteford H. A., Patton G. (2016). Preventing depression and anxiety in young people: A review of the joint efficacy of universal, selective and indicated prevention. Psychological Medicine, 46(01), 11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suldo S., Thalji A., Ferron J. (2011). Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver P., Schwartz J., Kirson D., O’Connor C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1061–1086. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suveg C., Sood E., Comer J. S., Kendall P. C. (2009). Changes in emotion regulation following cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(3), 390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaut M. (2013). Rhythm, music, and the brain: Scientific foundations and clinical applications. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Travis R., Jr. (2013). Rap music and the empowerment of today’s youth: Evidence in everyday music listening, music therapy, and commercial rap music. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 30(2), 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Travis R., Jr., Deepak A. (2011). Empowerment in context: Lessons from hip-hop culture for social work practice. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 20(3), 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Treffers P. D. A., Goedhart A. W., Veerman J. W., Van den Bergh B. R. H., Ackaert L., De Rycke L. (2004). Competentie belevingsschaal voor Adolescenten. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie, 7, 468–469. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig S. (2011). Rap & Singing for emotional and cognitive development of at-risk-children. In Baker F., Uhlig S. (Eds.), Voicework in music therapy, research and practice (pp. 63–83). London, UK: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig S., Dimitriadis T., Hakvoort L., Scherder E. (2016). Rap and singing are used by music therapists to enhance emotional self-regulation of youth: Results of a survey of music therapists in the Netherlands. Arts in Psychotherapy, 53, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig S., Jansen E., Scherder E. (2015). Study protocol RapMusicTherapy for emotion regulation in a school setting. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 1068–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig S., Jaschke A., Scherder E. (2013). Effects of music on emotion regulation: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Music & Emotion Finland: University of Jyväskylä, Department of Music. [Google Scholar]

- UK Parliament. (2014). Children’s and young people’s mental health in 2014. Retrieved from https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmselect/cmhealth/342/34205.htm

- Veerman J. W. (1989). Zelfwaardering bij klinische en niet-klinische groepen: Een onderzoek met de Competentiebelevingsschaal voor kinderen. Kind en Adolescent, 10, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Viega M. (2013). Loving me and my butterfly wings: A study of Hip-Hop songs written by adolescents in music therapy (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Temple University, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Viega M. (2015). Exploring the discourse in hip hop and implications for music therapy practice. Music Therapy Perspectives, 34(2), 138–146. [Google Scholar]

- Vohs K. D., Baumeister R. F. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wan C. Y., Schlaug G. (2010). Music making as a tool for promoting brain plasticity across the life span. The Neuroscientist, 16(5), 566–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A., Klonsky E. D. (2009). Measurement of emotion dysregulation in adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 616–621. doi: 10.1037/a0016669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (n.d.). Defining adolescents health and ages 10–19. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/en/

- Zimmermann P., Iwanski A. (2014). Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(2), 182–194. [Google Scholar]