Abstract

Objective:

Several studies have shown a relationship between individual attachment and various aspects of treatment utilization in individuals with medical problems as well as mental health disorders. This review systematically evaluates existing literature targeting the relationship between attachment and all aspects of treatment utilization, such as engagement, participation, and completion, in adults with mental health problems.

Method:

A computerized search of PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, PubMed, and Healthstar and a manual search were employed. Of 5733 titles, 105 abstracts were selected. Of these, 18 studies met full inclusion criteria. The quality of studies was evaluated and scored according to 9 characteristics.

Results:

Most studies supported an association between attachment and treatment engagement and participation. In general, attachment anxiety was associated with higher engagement and participation in services while attachment avoidance was associated with less. Data regarding attachment dimensions and treatment completion were less conclusive.

Conclusions:

The review suggests a clear relationship between attachment and stages of treatment engagement and participation in a variety of psychiatric populations and treatments. The 2 attachment dimensions appear to have opposite effects, with possible risks for either treatment over- or underutilization. Clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: attachment, treatment, mental health, psychiatric services

Abstract

Objectif:

Plusieurs études ont démontré une relation entre l’attachement individuel et les divers aspects de l’utilisation des traitements chez les personnes ayant des problèmes médicaux ainsi que des troubles de santé mentale. Cette revue évalue systématiquement la littérature existante portant sur la relation entre l’attachement et tous les aspects de l’utilisation des traitements, comme l’engagement, la participation et l’achèvement, chez des adultes ayant des problèmes de santé mentale.

Méthode:

Une recherche informatique dans PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, PubMed et Healthstar ainsi qu’une recherche manuelle ont été menées. Sur 5 733 titres, 105 résumés ont été relevés. Sur ceux-ci, 18 études satisfaisaient à l’ensemble des critères d’inclusion. La qualité des études a été évaluée et cotée selon 9 caractéristiques.

Résultats:

La plupart des études soutenaient une association entre l’attachement et l’engagement et la participation au traitement. En général, l’attachement anxieux était associé à un engagement et une participation plus élevés aux services, alors que l’attachement d’évitement était associé à un engagement et une participation moindres. Les données sur les dimensions de l’attachement et l’achèvement du traitement étaient moins concluantes.

Conclusions:

La revue suggère une relation nette entre l’attachement et les stades de l’engagement et de la participation au traitement, dans une variété de populations et de traitements psychiatriques. Les deux dimensions de l’attachement semblent avoir des effets contraires, posant des risques possibles de surutilisation ou de sous-utilisation des traitements. Les implications cliniques sont présentées.

The success of the health care system is dependent on the relationship between care providers and patients.1 Similarly, within the mental health system, most decisions are made in the dyadic context of the therapeutic relationship. Still, the ultimate implementation of the treatments offered lies largely with the patient. While most research in mental health has focused on the outcomes of the treatments offered, little attention has been paid to the patient’s characteristics. This is highly surprising, since these very features are likely to affect the implementation of the recommended treatments and, therefore, contribute significantly to their success.

Attachment theory provides a good framework for understanding individual characteristics that can have a significant impact interpersonally, including on the therapeutic relationship. Attachment theory was first introduced by John Bowlby, who posited that infants develop a relational pattern based on the interactions they have with their caregivers.2 Based on these first interactions, children develop a sense of self in relationship to others and, as a result, a set of expectations with respect to the support and nurturance they can receive in times of need. This ‘safe base’ is the key to a healthy sense of trust of self and others, allowing children to gain confidence and gradually explore the world around them.2 Bowlby proposed that, when activated by a threat, the attachment system is reflected in thoughts and behaviour that lead to searching for proximity to attachment figures.3 These patterns of interaction form the basis for 2 attachment types, broadly called secure and insecure attachment styles. Secure attachment represents the healthy interpersonal style, whereas insecure attachment styles, based on their interpersonal characteristics, can be further divided into anxious and avoidant type, based on their characteristics. Studies have found that these early patterns are likely to persist over time and predict, to a moderate degree, the interpersonal response to attachment threats in adults.4 For instance, securely attached adults find it easy to seek support from close relationships when in need, feeling comfortable with intimacy and independence and having adaptive interpersonal approaches. Simply put, having a secure attachment style leads to a positive view of self and others. However, adults with a preoccupied style (also called anxious) tend to have a low sense of confidence in self but a high sense of trust in others. Preoccupied adults lack confidence in their independent coping and frequently resort to attention-seeking behaviours. They tend to fear the loss of love and support and engage in hyperactivating behaviours (e.g., exaggerating the strength of the threat, asking for reassurance) to maintain their sense of safety in relationships. In contrast, the dismissing (also called avoidant) style is associated with having a high sense of confidence in self but a low sense of trust in others. This leads to excessive self-reliance in times of distress, when the individual elects to cope alone, frequently downplaying the severity of the stressor or his or her feelings towards it. In summary, avoidantly attached adults engage in hypoactivating strategies, by devaluing a perceived threat and inhibiting their response(s) to it. As a result, these individuals tend to isolate themselves from others when support may be beneficial.4 Finally, fearful attachment style (also called disorganized) is made up of elements of both avoidant and anxious attachment styles, with individuals having a negative view of self and others. Fearful individuals desire closeness but are unable to achieve it, oscillating between a need for intimacy and a rejection of it, which often results in sabotaged relationships.

Measures of adult attachment have been broadly defined as categorical and dimensional. Categorical measures typically ask respondents to classify themselves into the 4 attachment styles (secure, preoccupied, dismissing, and fearful) based on brief descriptions of each type (e.g., Relationship Questionnaire).5 Dimensional aspects of attachment (i.e., attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance) have been amply explored in research and found to be more accurate compared to categorical measurements (i.e., attachment styles), which are more user-friendly and relevant from a clinical perspective. For a thorough review of attachment measures, see Ravitz et al.6

According to attachment theory and research, the patterns of interpersonal relationships specific to different attachments may be important determinants of illness behaviour, care seeking, and treatment response in patients.7 Specifically, looking at the impact of attachment in medical patients, research has shown that insecure attachment can lead to poorer treatment adherence, greater treatment costs, and utilization in medical outpatients.7–9 For example, Ciechanowski et al.10 found that patients with preoccupied and fearful attachment styles have the highest reporting of physical symptoms compared to secure patients. In addition, patients with preoccupied attachment had the highest primary care costs and utilization, whereas patients with fearful attachment had the lowest, the latter being noted to frequently miss previously scheduled appointments.

With respect to mental health, most studies have focused on the relationship between attachment and therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy.11–18 In fact, the relationship between attachment and therapeutic alliance has been amply reviewed previously and will not be discussed here.19 Few studies have investigated the relationship between attachment and other aspects of mental health treatment, such as treatment seeking, compliance, and treatment costs.20 There is a lack of synthesis and critical evaluation of findings pertaining to the relationship between attachment and mental health utilization.

This systematic review aims to explore the relationship between adult attachment and any type of mental health treatment utilization and to discuss issues existing in the current stage of the literature. When defining treatment utilization, we followed the advice of Andersen and Newman,21 who recommend that the variables of interest must be carefully chosen and may include whether treatment was received, if at all; the frequency of treatment access (e.g., number of appointments attended); and compliance with treatment (e.g., medication adherence). As a result, we classified treatment utilization as falling under 3 groups: treatment engagement, treatment participation, and treatment completion.21

Methods

The process and reporting of systematic review results were guided by the PRISMA guidelines, 2009 revision.22

Search Strategy

Two methods (computerized and manual search) were used to ensure a thorough coverage of the relevant literature. First, a computerized search was conducted to identify relevant peer-reviewed journal articles describing the relationship between attachment and mental health service utilization. Databases including PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, PubMed, and Healthstar were searched using the keywords ‘attachment’ AND ‘service OR utilization OR health care system OR hospitalization OR treatment OR psychotherapy OR psychopharmacology OR cognitive therapy OR behavior therapy OR group therapy OR ECT’ AND ‘mental OR psycholo* OR psychiatri*’. Second, a manual search using unpublished sources, such as those identified by Google Scholar, was conducted to identify additional papers. Reference lists in the relevant reviews were also searched for additional articles. The search included articles published up to March 31, 2017, and resulted in the identification of 5733 potential articles.

Inclusion Criteria

The following 4 inclusion criteria were used to evaluate the eligibility of identified articles: 1) used a cohort, or case-control, or cross-sectional study design; 2) studied adult subjects (aged 18 to 65 years old); 3) used a standard questionnaire or scale to measure adult attachment and utilization of mental health treatments; and 4) published in English with full text available.

Exclusion Criteria

This review excluded articles if they 1) were case reports or qualitative studies and 2) did not provide a statistical indicator (i.e., relative risk) to estimate the relationship between adult attachment and utilization of mental health treatment.

Studies Selection

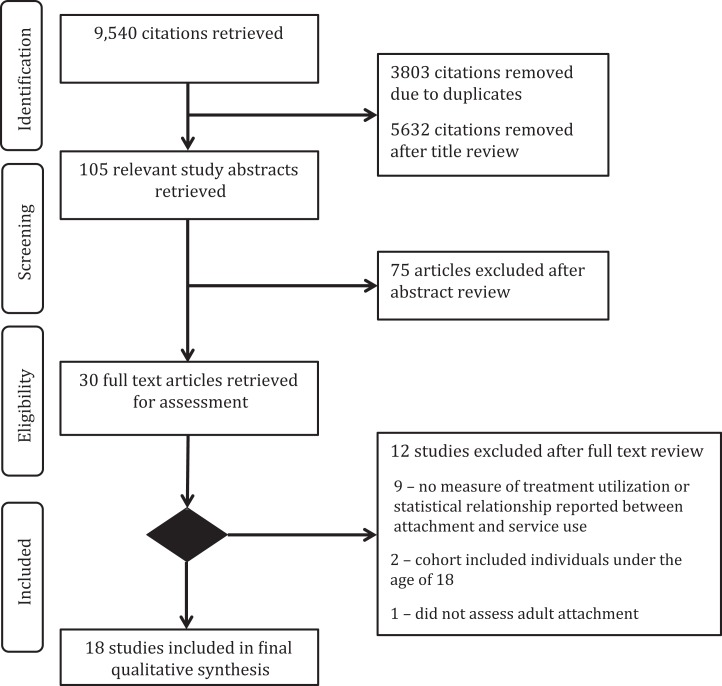

One author (A.W.) identified relevant titles meeting inclusion criteria. All authors independently reviewed the abstracts to determine which articles should be reviewed in full. Any discrepancies in the decision to include or exclude articles were discussed and resolved. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process of articles.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of article selection process.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data on authors, year of publication, study design, sample size, mental health complaint, measure of adult attachment, mental health service use, and major findings were extracted from selected articles. In a few instances, corresponding authors were contacted for further clarification of information not reported in the studies (e.g., age range of the samples). We evaluated the heterogeneity of selected studies for the following characteristics, including study subjects, measurements of adult attachment, diagnosis of mental health problems, and measurements of mental health treatments. There was a high level of heterogeneity for the above characteristics, therefore preventing the use of meta-analysis in this review. Higgins et al.23 suggest that when there are differences in study characteristics, the underlying assumption of random-effects models is violated. Therefore, a qualitative approach was applied to summarize the findings of this review.

A study quality assessment checklist was developed based on the following 9 study characteristics: target population (e.g., general population vs. clinical samples), sample size, whether or not use of a longitudinal study design was employed, whether or not an appropriate attachment measurement was used, whether or not mental health disorder was diagnosed, whether or not mental health service use was assessed, whether or not multiple diagnoses were considered, whether or not appropriate statistical analyses were used, and whether or not an appropriate method for controlling for potential confounders (e.g., age, gender) was employed. The total score of the study quality checklist was 9, with an assumption of each characteristic contributing equally to study quality. In addition, to examine the impact on different stages of treatment, the components of treatment utilization reported were classified under 3 main categories: 1) treatment engagement (i.e., the seeking of professional help and the initiation of treatment), 2) treatment participation (i.e., the extent to which treatment was used, generally being measured with the frequency and/or length of appointments), and 3) treatment completion (i.e., the likelihood to follow through or not with treatment until its recommended end). Researchers were blind to attachment status when categorizing the studies. The classification of the studies was only made according to the above preestablished definitions. Information regarding attachment was extracted after classification was completed.

Results

The initial search identified a total of 5733 titles. After reviewing the 5733 titles, 105 abstracts were selected. After reviewing the abstracts, 18 articles met inclusion criteria and were fully evaluated for the review. The median quality score was 5.5 out of 9, with 50% of studies having the average quality. Most studies (15/18, 83%) had clear information on diagnoses of mental disorders or mental health concerns.20,24–37 The remaining 3 articles used a broad definition of mental health (e.g., ‘a mental health concern’)38,39 or enrolled individuals following a suicide attempt and/or potentially traumatic event.40 Ten different questionnaires/scales were used to measure attachment. The majority of articles (10/18, 56%) used a dimensional measure of attachment. The most common measure of attachment was the Experiences in Close Relationships scale (4/18, 22%). Table 1 illustrates the detailed information of selected articles.

Table 1.

Summary of Articles Included in the Review.

| Authors | Year | Sample Size | Study Design | Measurements of Adult Attachment | Subtypes of Adult Attachment | Utilization of Mental Health Treatment | Diagnosis of Mental Health Problems | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment engagement | ||||||||

| Caspers et al.25 | 2006 | 208 | Cross-sectional | AAI | Preoccupied/earned secure, continuous secure, dismissing | Contact with mental health professionals and use of outpatient treatment services | Substance use disorder | Odds of speaking to a mental health professional or participating in outpatient treatment were 4.5 and 3 times more likely, respectively, for those who were classified as preoccupied/earned secure (both P = 0.001). Within individuals with substance use disorders only, dismissing participants were less likely to engage in treatment compared to preoccupied or earned secure (P = 0.015). |

| Dozier26 | 1990 | 42 | Cross-sectional | AAI | Preoccupied, secure, dismissing | Use of the public mental health system | Mood and psychotic disorders | Individuals with higher attachment avoidance were less likely to seek help or more likely to reject it when offered (P < 0.001). Securely attached individuals had greater rates of compliance with treatment (P < 0.05). |

| Franz39 | 2012 | 258 | Longitudinal | ECR-R | Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions | Reception of any mental health treatment | General mental health concerns | Higher attachment anxiety related to higher levels of intention to seek help (P < 0.001). Neither attachment dimension was a predictor of treatment engagement (P > 0.05). Attachment was not a predictor of having sought help at follow-up (P > 0.05). Attachment avoidance moderated the relationship between distress and help-seeking intent (P < 0.01). |

| Goodwin and Fitzgibbons28 | 2002 | 28 | Cross-sectional | BORI | Dimensional measure of attachment insecurity | Entry into outpatient program for eating disorders | Eating disorders | A higher score on the Insecure Attachment subscale was associated with a lower likelihood of entering treatment (P < 0.05). |

| Huang et al.37 | 2013 | 16 | Cross-sectional | ECR | Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions | Engagement with outpatient psychotherapy | Depression, anxiety, life stressors | Attachment anxiety was higher in treatment nonengagers than engagers (P = 0.047). There was no difference in attachment avoidance between engagers and nonengagers (P > 0.05). |

| Meng et al.31 | 2015 | 5645 | Cross-sectional | Hazan and Shaver Self-reported Attachment Style Measure | Secure, anxious, avoidant | Inpatient and outpatient treatment utilization | Depression, anxiety, substance abuse | Individuals with either anxious or avoidant attachment were more likely to have used a hotline, have had a session of psychological counseling or therapy that lasted 30 minutes or longer, and have gotten a prescription for medicine for emotions, nerves, mental health, or substance use from any type of professional (all P < 0.05). |

| Tait et al.35 | 2004 | 50 | Longitudinal | RAAS | Secure and insecure attachment styles | Engagement with mental health services | Psychosis | Participants with insecure attachment style were less likely to engage with services (P < 0.001). |

| Vogel and Wei38 | 2005 | 355 | Cross-sectional | ECR | Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions | Intent to seek help for mental health concerns | Nonspecific (undergraduate students) | Greater attachment avoidance was correlated with lower intention of seeking help (P < 0.05). Attachment anxiety was correlated with increased intention to seek counseling (P < 0.001). High attachment anxiety and avoidance were related to perceived lack of social support. This resulted in increased distress, which in turn increased the intent to seek help (P < 0.01). |

| Treatment participation | ||||||||

| Berry et al.20 | 2014 | 25 | Cross-sectional | PAM | Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions | Participation in community-based mental health team services | Psychosis | Attachment anxiety was positively correlated with number of times services were used, the number of hours used, and cost (all P ≤ 0.04). Avoidant attachment was significantly correlated with number of times services were used and number of hours used (both P < 0.05). After controlling for psychopathology, only correlations between anxious attachment and number of times and hours of use remained significant (P < 0.05). |

| Ilardi and Kaslow40 | 2009 | 51 | Longitudinal | RSQ | Secure, preoccupied, dismissing, fearful | Outpatient psychotherapy | Women with suicide attempts | Participants with insecure attachment style, predominately fearful, had the lowest attendance rate (P < 0.05). |

| Jenkins and Tonigan34 | 2011 | 239 | Longitudinal | RQ | Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions | Alcoholics Anonymous attendance | Higher RQ avoidance was associated with less frequent Alcoholics Anonymous meeting attendance (P < 0.001). No such relationship existed between attachment anxiety and attendance (P > 0.05). | |

| Meng et al.31 | 2015 | 5645 | Cross-sectional | Hazan and Shaver Self-reported Attachment Style Measure | Secure, anxious, avoidant | Inpatient and outpatient treatment utilization | Depression, anxiety, substance abuse | Individuals with either anxious or avoidant attachment were more likely to have had a session of psychological counseling or therapy that lasted 30 minutes or longer (P < 0.05). |

| Treatment completion | ||||||||

| Bernecker et al.24 | 2014 | 69 | Longitudinal | ECR-R and RSQ | Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions | Outpatient CBT or IPT group therapy | Depression | There were no differences in attachment between those who dropped out or completed treatment (P > 0.05). |

| Fowler et al.27 | 2013 | 187 | Cross-sectional | RQ-15 | Secure, preoccupied, dismissing, fearful | Inpatient treatment for concurrent disorders | Concurrent disorders | Individuals with anxious-preoccupied attachment style were more likely to complete treatment (P < 0.05). |

| Hoyer et al.29 | 2015 | 183 | Longitudinal | ECR-R | Attachment anxiety and avoidance dimensions | Outpatient treatment | Social phobia | Attachment was not a predictor of dropout (P > 0.05). |

| Illing et al.30 | 2010 | 157 | Cross-sectional and longitudinal components | ASQ | Attachment security, anxiety, and avoidance dimensions | Outpatient group therapy | Eating disorders | There were no differences in attachment between those who dropped out or completed treatment (P > 0.05). |

| Maxwell et al.32 | 2017 | 202 | Cross-sectional | AAI | Secure, preoccupied, dismissing, unresolved/disorganized, cannot classify | Outpatient group therapy | Binge-eating disorder | There were no differences in attachment between those who dropped out or completed treatment (P > 0.05). |

| Potik et al.33 | 2014 | 101 | Longitudinal | VASQ | Vulnerable attachment style | Methadone maintenance treatment | Substance dependence | There were no differences in attachment between those who dropped out or completed treatment (P > 0.05). |

| Tasca et al.36 | 2004 | 74 | Cross-sectional | ASQ | Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions | Partial hospital treatment program | Anorexia nervosa | Higher avoidant attachment predicted dropout from treatment for those with AN binge-purge subtype (ANB; P < 0.05). However, this relationship did not emerge for those with AN restricting subtype (ANR). Higher anxious attachment predicted treatment completion for those with ANB (P < 0.001) but not for those with ANR (P > 0.05). |

AAI, Adult Attachment Interview; AN, anorexia nervosa; ASQ, Attachment Style Questionnaire; BORI, Bell Object Relations Inventory; CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationships; ECR-R, Experiences in Close Relationships–Revised; IPT, Interpersonal Psychotherapy; PAM, Psychosis Attachment Measure; RAAS, Revised–Adult Attachment Scale; RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; RQ-15, Relationship Questionnaire–15; RSQ, Relationship Scales Questionnaire; VASQ, Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire.

In general, the 18 studies examined a wide range of mental health treatment utilizations. Their classification included 8 studies on treatment engagement,25,26,28,31,35,37–39 4 studies on treatment participation,20,31,34,40 and 7 studies on treatment completion.24,27,29,30,32,33,36 The research findings are summarized below according to the specific treatment utilization category researched.

Attachment and Treatment Engagement

All 8 studies found statistically significant relationships between attachment and treatment engagement.25,26,28,31,35,37–39 Five articles assessed treatment initiation,25,28,31,35,37 2 assessed the intent to seek help,38,39 and 1 assessed both of these behaviours.26

In general, people with higher attachment anxiety had greater treatment engagement, whereas people with greater attachment avoidance tended to reject help when offered and be less engaged with treatment. Two studies found a positive relationship between attachment anxiety and service engagement25,31; 3 articles found a negative relationship between attachment avoidance and intent to seek help,26,38,39 as well as service engagement26; only 1 study found a positive relationship between attachment avoidance and service engagement31; and 2 found a negative relationship between general attachment insecurity and treatment engagement.28,35 The only study using categorical measures suggested that individuals with secure attachment had greater rates of compliance with treatment.35 The study populations varied, including undergraduates, individuals with general mental health concerns, and more specific populations with psychotic and mood disorders. These studies had an average quality score of 5.5.

Attachment and Treatment Participation

All 4 studies found significant relationships between attachment and treatment participation.20,31,34,40 The operationalization of treatment participation included group attendance, frequency and length of appointments and their associated costs, and likelihood of having an appointment with a mental health professional that was longer than 30 minutes. The study populations of interest varied, ranging from general population to specific samples of individuals with psychosis, suicidality, or alcohol use disorders. Generally, individuals with higher attachment anxiety were more likely to participate in treatment, whereas people with higher attachment avoidance were less likely to participate.

Higher attachment avoidance was associated with lower attendance at weekly outpatient psychotherapy34 and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.40 The authors note that individuals with fearful attachment style attended the fewest Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

Berry et al.20 found that both dimensions of attachment correlated with the number of times services were accessed as well as the length of appointments, while attachment anxiety also correlated with the cost to provide services. However, after controlling for psychopathology, only the relationship between attachment anxiety and frequency and length of appointments remained significant. Meng et al.31 found similar results: higher attachment anxiety and avoidance was associated with having a greater likelihood of having had an appointment with a mental health professional that was longer than 30 minutes compared to individuals with secure attachment. These studies had an average quality score of 6.25.

Attachment and Treatment Completion

Seven articles assessed attachment in treatment completers compared to individuals who dropped out.24,27,29,30,32,33,36 Of these, only 2 studies found significant results.27,36 Five articles were based on outpatient psychotherapy programs,24,29,30,32,36 1 article assessed completion of an inpatient program,27 and 1 article investigated retention in a methadone maintenance program.33 Fowler et al.27 reported that individuals with an anxious attachment style were less likely to complete an inpatient treatment program. Conversely, Tasca et al.36 found that greater attachment anxiety predicted completion of a partial hospital treatment program in individuals with anorexia nervosa binge-purge subtype, while higher attachment avoidance predicted dropout. These studies had an average quality score of 6.14.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive systematic review to summarize the relationship between adult attachment and mental health treatment utilization. In general, we found the following: 1) most of the evidence supported a relationship between adult attachment and treatment engagement and participation, 2) there were less conclusive findings on the relationship between attachment and treatment completion, 3) individuals with greater attachment anxiety were likely to have greater treatment engagement and participation, 4) individuals with greater attachment avoidance were less likely to look for help when faced with mental health concerns and less likely to comply with or complete the treatments, and 5) individuals with secure attachment had the best treatment engagement while fearful individuals were the least likely to use treatment services.

This literature review largely suggests opposite effects of the 2 main dimensions of attachment, anxiety and avoidance, on the level of treatment utilization. Overall, individuals with higher attachment anxiety were likely to have greater engagement with mental health services, greater frequency of use and length of appointments, and increased treatment completion. On the other hand, individuals with higher attachment avoidance were less likely to look for help when faced with mental health concerns and less likely to comply with or complete the treatments compared with those with preoccupied attachment styles or higher attachment anxiety. In line with findings with previous studies in medical patients, individual attachment was associated with service utilization and costs, generally with opposite effects between anxious and avoidant attachment.7,41–43 Unfortunately, in the current review, only 1 article assessed the association between attachment and cost to treat. The results were correlative, and the cost of treatment was not reported.20 However, in a study investigating the relationship between attachment and primary care visit costs, preoccupied individuals had the highest costs while fearful individuals had the lowest, over a 1-year period.10 Specifically, preoccupied individuals cost 43% more to treat in primary care settings than fearful individuals. Therefore, future work should evaluate this relationship with respect to incurred mental health service costs.

When looking at the expression of health behaviours according to attachment organization, it is important to remark the striking similarity between the way people relate to mental health care providers and the way they relate in their close relationships. For instance, the behaviour of help seeking and use of supportive services is very similar to the prototypical behaviour of individuals with higher attachment anxiety, who are likely to seek comfort or support when distressed, while the lack of treatment engagement, poor participation, and early dropout are in keeping with the dismissal of support and sharing of avoidantly attached individuals. While these relational patterns have been noticed and largely explored in the context of relational treatments (e.g., psychotherapy), less attention has been paid to their impact on biological treatments or overall treatment utilization. A recent study showed that attachment dimensions are associated with not only the number of professionals seen but also the number of psychiatric medications used. Consistent with the current findings, attachment anxiety was positively associated with the number of psychiatric medications being taken and the number of professionals seen, while attachment avoidance was negatively associated with the number of psychiatric medications being currently taken.44 Research looking at the impact of attachment on views of health care providers found that patient attachment anxiety and avoidance were positively correlated with wanting closer contact with their physician as well as viewing their contact with the health care provider as an aversive experience.45 This wanting of closeness but labeling the interaction as aversive mirrors the fearful attachment style, where there is low confidence in self but also a lack of trust in others. Interestingly, seeing healthcare providers as supportive and wanting greater contact with them was associated with more appointments. However, having aversive experiences with providers was not associated with number of visits. This further suggests that any type of treatment recommendation has to take into account the patient’s attachment and, therefore, consider the relational aspects of the therapeutic relationship as inherent to any recommendation.

Since attachment insecurity seems to be generally related to the symptom severity, a natural question that follows is to what extent symptom severity in itself affects attachment and treatment utilization. Importantly, several studies statistically controlled for levels of symptom severity and sociodemographic variables20,31 and still found that attachment, not symptoms, were related to mental health service utilization. Unfortunately, even though the history of trauma is highly relevant for the development of attachment insecurity, most studies did not assess for it or report the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. The mechanism through which attachment style influences help-seeking behaviours appears complex. The observation that insecure attachment is related to poor social support suggests either a difficulty in developing this support or a result of its absence.38 Moreover, it is this lack of support that ultimately perpetuates lack of trust and difficulty in relatedness. These interpersonal problems are further translated into similar difficulties when accessing health support. Seeing the health care provider as an attachment figure and the therapeutic relationship as the context in which attachment needs can be explored and understood might provide a unique opportunity for interpersonal healing, In fact, Maunder and Hunter45 showed that patients often experience their health care providers as having characteristics associated with the ‘secure base and safe haven’ evocative of the trusted intimacy of attachment relationships and that patients’ attachment characteristics shape these views and the desired level of contact with health care providers.

Finally, while individualized treatment approaches that take attachment characteristics into account seem logical, specific components remain to be determined and tested. In our clinical experience, several options might have merit depending on the context. For instance, increased clinical efforts at engaging avoidant patients in treatment through perseveration and accommodation might prove beneficial. For instance, follow-up phone calls after difficult sessions or missed appointments, as well as matching the treatment with the level of tolerated intimacy and disclosure (online therapy vs. individual therapy vs. group therapy), might prove beneficial. On the other hand, interpersonal and interpretative approaches meant to educate preoccupied and fearful patients of their impact on others might bring awareness and help contain strong and alienating expression of emotions. Last, psychoeducation regarding attachment styles might prove an easy tool in helping all patients reflect on their interpersonal views and behaviours.

Strengths and Limitations

The current review is the first study to use a systematic approach to explore the relationship between adult attachment and utilizations of mental health treatments. Furthermore, it provides synthesized results on the relationships between attachment dimensions and a full list of treatments.

There are a few limitations to note. First, the high heterogeneity of studies’ characteristics (i.e., measurements of adult attachment, diagnoses of mental health problems, study subjects, measurements of treatments, etc.) did not allow for meta-analysis, as biases would have been introduced into the pooled results. Moreover, the wide heterogeneity of the studied populations and treatments precludes the generalizability as well as the specificity of the conclusions that can be drawn from these results. Although general patterns of relationships between attachment and treatment utilization can be gleaned from this review, drawing specific recommendations for disorder or treatment type would be premature. Second, the total number of articles meeting inclusion criteria was relatively small, and the quality of selected studies varied from low to high. In particular, the relationship between attachment and treatment participation was addressed by only 4 articles. Although all 4 articles reported significant results, with half of them presenting longitudinal data, the studies were of modest quality (median = 5.5), raising questions about the generalizability of the findings. Third, there was no study that followed participants from preengagement with services through treatment completion, so the conclusions related to the influence of attachment throughout the mental health service utilization process were made from the observations of multiple studies.

Practical Implications of This Review

Clinicians would benefit from assessing attachment in clinical practice. Understanding patients’ attachment needs might help them in understanding difficulties with treatment compliance, including underutilization or excessive use. Focusing on building security and trust in the therapeutic relationship before any treatment recommendations are considered, as well as psychoeducation regarding attachment, might prove to improve all aspects of treatment utilization.

Conclusions

Overall, findings of this review follow a consistent and predictable pattern, suggesting that a relationship between adult attachment and mental health treatment utilization exists. Notably, this review cannot conclude whether anxiously attached individuals have excessive or unnecessary use of mental health services or if avoidant individuals are largely undertreated for their mental health problems. Unlike physical health problems, quantifying what is ‘just right’ for mental health services is more subjective (i.e., patient’s experience, clinician’s opinion). This review suggests that attachment can be viewed as a ubiquitous transdiagnostic behavioural pattern, providing support for the greater role of relational emphasis in mental health services.

Acknowledgements

We thank Donna Malcom, MD, for her generous donation to the College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, which funded the ‘Psychotherapy Outcome in Clients with Anxiety and Depression’ award.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funding in part by the grant ‘Psychotherapy Outcome in Clients with Anxiety and Depression’ award to the first author by the College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan.

ORCID iD: G. Camelia Adams,  http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5253-1426

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5253-1426

References

- 1. Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, et al. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol 1. Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bowlby J. A secure base: parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: structure, dynamics, and change. 2nd ed New York, NY: Guilford; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model childhood attachment and internal models. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(2):226–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ravitz P, Maunder R, Hunter J, et al. Adult attachment measures: a 25-year review. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(4):419–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciechanowski P, Sullivan M, Jensen M, et al. The relationship of attachment style to depression, catastrophizing and health care utilization in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2003;104(3):627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bennett JK, Fuertes JN, Keitel M, et al. The role of patient attachment and working alliance on patient adherence, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life in lupus treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(1):53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ciechanowski PS, Walker EA, Katon WJ, et al. Attachment theory: a model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, et al. Where is the patient? The association of psychosocial factors and missed primary care appointments in patients with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berry K, Barrowclough C, Wearden A. Attachment theory: a framework for understanding symptoms and interpersonal relationships in psychosis. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(12):1275–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berry K, Drake R. Attachment theory in psychiatric rehabilitation: informing clinical practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2010;16(4):308–315. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campbell R, Allan S, Sims P. Service attachment: the relative contributions of ward climate perceptions and attachment anxiety and avoidance in male inpatients with psychosis. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2014;24(1):49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daniel SIF. Adult attachment patterns and individual psychotherapy: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(8):968–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levy KN, Ellison WD, Scott LN, et al. Attachment style. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(2):193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma K. Attachment theory in adult psychiatry. Part 2: Importance to the therapeutic relationship. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(1):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salmon P, Young B. Dependence and caring in clinical communication: the relevance of attachment and other theories. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schuengel C, van IJzendoorn MH. Attachment in mental health institutions: a critical review of assumptions, clinical implications, and research strategies. Attach Hum Dev. 2001;3(3):304–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diener MJ, Monroe JM. The relationship between adult attachment style and therapeutic alliance in individual psychotherapy: a meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2011;48(3):237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berry K, Roberts N, Danquah A, et al. An exploratory study of associations between adult attachment, health service utilisation and health service costs. Psychosis. 2014;6(4):355–358. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):1-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2009;172(1):137–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bernecker SL, Levy KN, Ellison WD. A meta-analysis of the relation between patient adult attachment style and the working alliance. Psychother Res J Soc Psychother Res. 2014;24(1):12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Caspers KM, Yucuis R, Troutman B, et al. Attachment as an organizer of behaviour: Implications for substance abuse problems and willingness to seek treatment. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2006;1:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dozier M. Attachment organization and treatment use for adults with serious psychopathological disorders. Dev Psychopathol. 1990;2(1):47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fowler JC, Groat M, Ulanday M. Attachment style and treatment completion among psychiatric inpatients with substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2013;22(1):14–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodwin RD, Fitzgibbon ML. Social anxiety as a barrier to treatment for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32(1):103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoyer J, Wiltink J, Hiller W, et al. Baseline patient characteristics predicting outcome and attrition in cognitive therapy for social phobia: results from a large multicentre trial. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015;23(1):35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Illing V, Tasca GA, Balfour L, et al. Attachment insecurity predicts eating disorder symptoms and treatment outcomes in a clinical sample of women. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(9):653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meng X, D’Arcy C, Adams G. Associations between adult attachment style and mental health care utilization: findings from a large-scale national survey. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(1-2):454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maxwell H, Tasca GA, Grenon R, et al. Change in attachment states of mind of women with binge-eating disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017;24(6):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Potik D, Peles E, Abramsohn Y, et al. The relationship between vulnerable attachment style, psychopathology, drug abuse, and retention in treatment among methadone maintenance treatment patients. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(4):325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jenkins COE, Tonigan JS. Attachment avoidance and anxiety as predictors of 12-step group engagement. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(5):854–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P. Adapting to the challenge of psychosis: personal resilience and the use of sealing-over (avoidant) coping strategies. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tasca GA, Taylor D, Ritchie K, et al. Attachment predicts treatment completion in an eating disorder partial hospital program among women with anorexia nervosa. J Pers Assess. 2004;83(3):201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang T, Hill C, Gelso C. Psychotherapy engagers versus non-engagers: differences in alliance, therapist verbal response modes, and client attachment. Psychother Res. 2013;23(5):568–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vogel DL, Wei M. Adult attachment and help-seeking intent: the mediating roles of psychological distress and perceived social support. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(3):347–357. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Franz A. Predictors of help-seeking behavior in emerging adults. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ilardi DL, Kaslow NJ. Social difficulties influence group psychotherapy adherence in abused, suicidal African American women. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(12):1300–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, et al. Influence of patient attachment style on self-care and outcomes in diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(5):720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, et al. The patient-provider relationship: attachment theory and adherence to treatment in diabetes. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(1):29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ciechanowski PS. Attachment theory: a model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Adams GC, McWilliams LA, Wrath AJ, et al. Relationships between patients’ attachment characteristics and views and use of psychiatric treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maunder RG, Hunter JJ. Can patients be “attached” to healthcare providers? An observational study to measure attachment phenomena in patient-provider relationships. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]