Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. One AD hallmark is the aggregation of β-amyloid (Aβ) into soluble oligomers and insoluble fibrils. Several studies have reported that oligomers rather than fibrils are the most toxic species in AD progression. Aβ oligomers bind with high affinity to membrane-associated prion protein (PrP), leading to toxic signaling across the cell membrane, which makes the Aβ–PrP interaction an attractive therapeutic target. Here, probing this interaction in more detail, we found that both full-length, soluble human (hu) PrP(23–230) and huPrP(23–144), lacking the globular C-terminal domain, bind to Aβ oligomers to form large complexes above the megadalton size range. Following purification by sucrose density–gradient ultracentrifugation, the Aβ and huPrP contents in these heteroassemblies were quantified by reversed-phase HPLC. The Aβ:PrP molar ratio in these assemblies exhibited some limited variation depending on the molar ratio of the initial mixture. Specifically, a molar ratio of about four Aβ to one huPrP in the presence of an excess of huPrP(23–230) or huPrP(23–144) suggested that four Aβ units are required to form one huPrP-binding site. Of note, an Aβ-binding all-d-enantiomeric peptide, RD2D3, competed with huPrP for Aβ oligomers and interfered with Aβ–PrP heteroassembly in a concentration-dependent manner. Our results highlight the importance of multivalent epitopes on Aβ oligomers for Aβ–PrP interactions and have yielded an all-d-peptide–based, therapeutically promising agent that competes with PrP for these interactions.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, amyloid-β (Aβ), atomic force microscopy (AFM), oligomerization, protein aggregation, protein-protein interaction, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), D-enantiomeric peptides, density gradient ultracentrifugation (DGC), prion protein

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) 2 is the most common cause of dementia in the elderly population. One of its hallmarks is the accumulation of extracellular neuritic plaques consisting mainly of fibrillar β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide (1). Initially, these plaques were thought to be the toxic species in AD, but several lines of evidence now indicate that the levels of soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ (Aβoligo) correlate best with the neurotoxic effects observed during AD (2, 3).

Many Aβ receptors have been described to date (4). One of them is the cellular prion protein (PrPC), which binds Aβoligo with nanomolar affinity (5–10). PrPC is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored glycoprotein highly expressed in the brain. PrPC itself can misfold into the scrapie isoform PrPSc sporadically or after infection, leading to neuronal damage and disease such as the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (11). The interaction of Aβoligo with PrPC bound to the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 leads to toxic signaling across the cell membrane by activating intracellular Fyn kinase (12, 13). Fyn kinase phosphorylates N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (14, 15) and alters NMDA receptor localization, leading to destabilization of dendritic spines (12). Furthermore, Fyn kinase hyperphosphorylates the tau protein, which assembles into neurofibrillary tangles, a further hallmark of AD (16). Hyperphosphorylation of tau depends on the Aβ–PrP interaction (17). Therefore, understanding the Aβ–PrP pathway will open new therapeutic strategies by targeting the Aβ–PrP interaction (18).

The binding regions of Aβoligo have been mapped to residues 23–27 and ∼95–110 in the N-terminal part of PrP (5, 19–22) (see Fig. 1A). Soluble N-terminal PrP fragments inhibit the assembly of Aβ into amyloid fibrils and block neurotoxic effects of soluble oligomers (20, 23), presumably by competing with membrane-anchored PrPC for Aβoligo. This competition might also explain the suggested neuroprotective function of the naturally produced soluble N1 fragment (amino acids 23–110/111) of PrP (24), which contains both Aβoligo-binding regions. The binding regions on Aβ, however, have not been identified so far and might constitute a specific conformational epitope of Aβoligo (21). All these data show that the Aβ–PrP interaction is a promising point of intervention to prevent the toxic signaling in AD.

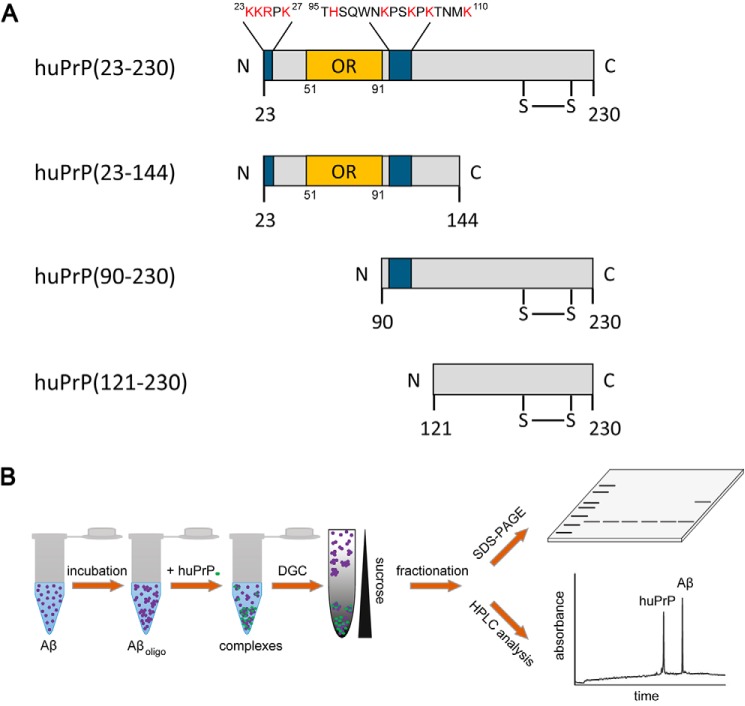

Figure 1.

Schematics of the investigated huPrP constructs huPrP(23–230), huPrP(23–144), huPrP(90–230), and huPrP(121–230) (A) and of the assay to quantify the composition of heteroassemblies (B). A, the binding sites for Aβ(1–42)oligo (5, 19–22) are marked in blue, and the corresponding sequence is shown in the huPrP(23–230) construct with basic amino acid residues highlighted in red. OR marks the octarepeat region from residues 51 to 91. huPrP(23–230), huPrP(90–230), and huPrP(121–230) contain a disulfide bond between Cys179 and Cys214 in the structured C-terminal part of the protein. B, 80 μm Aβ(1–42) was incubated for 2 h to obtain Aβ(1–42)oligo before different quantities of the respective prion protein were added to the sample. After 30-min coincubation, the sample was separated by sucrose DGC and fractionated. Each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE as well as by quantitative RP-HPLC.

In the past years, we have identified a number of d-enantiomeric peptides as promising drug candidates for direct elimination of Aβ(1–42)oligo (25–30). The advantage of d-peptides over l-peptides is their higher protease resistance, resulting in slower degradation and longer half-life (31, 32). For Aβ(1–42)-directed d-peptides, high stability in media simulating the route of orally administered drugs (33) and enhanced proteolytic stability in murine plasma and organ homogenates were shown (34). The lead compound of these d-peptides, D3, had been selected by mirror-image phage display (26, 35). D3 and its tandem version, D3D3, convert toxic Aβ species into nontoxic species (25, 28). Treatment with D3 reduces the number of amyloid plaques (26) and improves cognition in transgenic AD mice (28). One derivative of D3 called RD2 shows enhanced binding to Aβ (36, 37), and both RD2 and D3 have demonstrated desirable pharmacokinetic properties (29, 38). A further promising derivative is the d-peptide RD2D3, a head-to-tail tandem combination of RD2 and D3 (30, 34, 39). RD2D3 binds Aβ(1–42) with a KD of 486 ± 69 nm (39). All of these therapeutically promising d-peptides contain a high fraction of basic residues, which is reminiscent of the proposed binding sites for Aβ on PrP (5, 19–21). Therefore, the Aβ-binding d-peptides might be suitable compounds for interference with the Aβ–PrP interaction by competing with PrP for Aβ(1–42)oligo.

Recently, we introduced the “quantitative determination of interference with Aβ aggregate size distribution” (QIAD) assay, which allows the determination of a compound's efficacy to eliminate Aβ(1–42)oligo (25). This assay enables the separation of Aβ assemblies by density–gradient ultracentrifugation (DGC) and the quantification of these assemblies by UV-detected reversed-phase (RP)-HPLC. For the present study, we have refined the QIAD assay to achieve simultaneous quantification of Aβ(1–42), recombinant anchorless human PrP (huPrP) constructs, and d-peptides in a single RP-HPLC run to (i) characterize the Aβ-huPrP interaction in detail and (ii) evaluate the influence of the tandem d-peptide RD2D3 on this interaction. We investigated four different huPrP protein constructs, namely huPrP(23–230), huPrP(23–144), huPrP(90–230), and huPrP(121–230) (see Fig. 1A), and added them in different concentrations to preformed Aβ(1–42)oligo. In the case of huPrP(23–230) and huPrP(23–144), this resulted in high-molecular-weight Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP complexes. The separation of these complexes from Aβ(1–42) or huPrP monomers and Aβ(1–42)oligo by sucrose DGC and subsequent RP-HPLC analytics (see Fig. 1B) allowed the determination of molar ratios between Aβ(1–42) and huPrP within the complexes. We show that these ratios are dependent on the concentration of huPrP added. We imaged Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes by atomic force microscopy (AFM) and observed a correlation between the applied huPrP(23–144) concentration and the size and morphology of the heteroassemblies. We analyzed the influence of the d-peptide RD2D3 on the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) interaction by determining its effect on the Aβ(1–42):huPrP ratio within the assemblies. We show that RD2D3 competes with the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) interaction and might thus be a potential therapeutic agent.

Results

Aβ(1–42)oligo and all huPrP protein constructs are soluble when analyzed separately

In addition to full-length huPrP (huPrP(23–230)), three huPrP deletion constructs were investigated: the N-terminal fragment huPrP(23–144) and the C-terminal fragments huPrP(90–230) and huPrP(121–230) (Fig. 1A). huPrP(23–230) and huPrP(23–144) contain both regions (residues 23–27 and ∼95–110) described to be necessary for high-affinity binding of Aβ(1–42)oligo (5, 19–22). In huPrP(90–230), the N-terminal binding region (residues 23–27) is missing, whereas in huPrP(121–230) the second binding region (residues ∼95–110) is missing as well. All huPrP protein constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli. Therefore, they did not contain any posttranslational modifications (glycosylation or GPI anchor). They were purified either by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) or by size exclusion chromatography and subsequent RP-HPLC, yielding highly pure samples as confirmed by SDS-PAGE and analytical RP-HPLC (Fig. S1). The purified huPrP(23–230), huPrP(90–230), and huPrP(121–230) proteins contain the disulfide bond between Cys-179 and Cys-214 as confirmed by comparative RP-HPLC analyses of the purified versus their tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride–reduced states (Fig. S2).

Before investigating the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP interaction, we checked the binding partners separately in their purified states to confirm that they remain soluble at the chosen buffer conditions, which were a compromise between neutral pH and conditions required for stability of Aβ oligomers and detergent-free solubility of huPrP constructs favoring absence of phosphate and low salt. This is of note as all huPrP protein constructs (40–43) as well as Aβ (44, 45) are able to convert into fibrils under certain conditions, and such a conversion may hamper the analysis of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP complexes. We performed CD spectroscopy analysis of huPrP(23–144), huPrP(23–230), and huPrP(90–230); solution NMR spectroscopy of huPrP(23–144) and huPrP(23–230); and AFM measurements of huPrP(23–144).

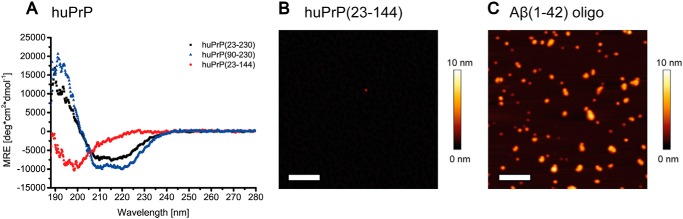

CD spectroscopy of huPrP(23–144) (Fig. 2A) indicated a disordered conformation at neutral pH, consistent with reports in the literature (46). In addition, AFM measurements of huPrP(23–144) confirm the absence of fibrils or large aggregates. Here, huPrP(23–144) forms a thin film on the mica surface with a height of 1–2 nm. Very rarely, single amorphous particles were observed (Fig. 2B). CD spectroscopy of the C-terminal huPrP(90–230) construct and full-length huPrP(23–230) (Fig. 2A) both showed the predominantly α-helical structures typical for the native prion protein fold (47) rather than the predominantly β-sheet conformation of amyloid fibrils.

Figure 2.

Analysis of purified huPrP by CD spectroscopy (A) and AFM (B) and of Aβ(1–42)oligo by AFM (C). huPrP(23–230) (A, black) and huPrP(90–230) (A, blue) show predominantly α-helical CD spectra, whereas the N-terminal huPrP(23–144) (A, red) is present in random-coil conformation (MRE, mean residue ellipticity; deg, degrees). Shown are 1-μm2 AFM images of 200 nm huPrP(23–144) (B) or 800 nm Aβ(1–42)oligo (C). Scale bars, 200 nm. huPrP(23–144) forms a thin film on the mica surface, not higher than 1–2 nm (B). The generated Aβ(1–42)oligo species are seen as spherical particles with heights ranging from 1 to 6 nm (C).

The solubility and overall conformational properties of huPrP(23–230) and huPrP(23–144) were confirmed in more detail by solution NMR spectroscopy. The solution structure of huPrP had originally been determined in acetate buffer at pH 4.5 and 20 °C (47) and found to comprise a highly disordered N-terminal region (residues 23–124) followed by a globular C-terminal domain (residues 125–228) featuring three long α-helices and a relatively small two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet. Under these buffer conditions, we indeed obtained well dispersed solution NMR spectra of excellent quality for huPrP(23–230) (Fig. S3A) with sharp narrow line shapes and chemical shifts similar to those reported in the literature (47), thereby demonstrating that the protein is soluble and natively folded. huPrP(23–144) also exhibits high-quality solution NMR spectra under these buffer conditions (Fig. S3A). As expected for huPrP(23–144), only backbone amide resonances in the random-coil region (1H chemical shifts between about 8.0 and 8.6 ppm (48)) were observed (Fig. S3A), suggesting that not only the N-terminal region from residues 23 to 124 is highly disordered but that also residues 125–144 are disordered in huPrP(23–144). To build a bridge between the quality control of the huPrP samples done at pH 4.5 and the solution conditions used for the interaction studies done at pH 7, we investigated the pH dependence of the overall conformational properties of huPrP(23–144) by solution NMR spectroscopy in a series of pH steps from 4.5 to 7.0. Although the shift in protonation equilibrium of the seven histidine side chains upon increasing the pH was associated with readily identifiable chemical shift changes for several backbone amide resonances, the quality and overall appearance of the solution NMR spectra of huPrP(23–144), including the limited resonance dispersion indicative of a disordered conformation, remained very similar over this pH range (Fig. S3B). Over the course of several days to weeks, the NMR samples did not show obvious signs of any significant formation of visible precipitate, any deterioration, or signal loss of the solution NMR spectra. To test for any sample degradation or aggregation in a more quantitative fashion, we monitored the intensity of 58 sufficiently well resolved amide resonances of a sample of 89 μm [U-15N]huPrP(23–144) in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, in 10% D2O in a series of 1H,15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectra recorded at 600 MHz at 5.0 °C, but no change in resonance intensity exceeding even a fraction of a percent was observed over the monitoring period of more than 48 h (Fig. S3D). Taken together, these NMR spectroscopic results show that huPrP(23–144) is readily soluble up to concentrations of about 0.3 mm, is highly disordered in solution under mildly acidic to neutral buffer conditions, and remains soluble and disordered for at least several days at the conditions tested.

Aβ(1–42)oligo was prepared by incubating monomeric Aβ(1–42) in buffer at pH 7.4 for 2 h at 22 °C under agitation. AFM of the Aβ(1–42)oligo samples showed small spherical particles with heights of 1–6 nm, rarely up to 10 nm (Figs. 2C and S4) and confirmed that the chosen incubation conditions produce high amounts of Aβ(1–42)oligo without formation of Aβ(1–42) fibrils or larger aggregates.

Our assay for studying the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP interaction is based on the QIAD protocol (25). In the present work, this assay includes the separation of a sample containing Aβ(1–42) assemblies and/or huPrP by sucrose DGC followed by qualitative and quantitative analyses of the interaction partners by SDS-PAGE and RP-HPLC (Fig. 1B). For calibration of the sucrose gradient, standard proteins ranging from 43 to 669 kDa were used (Fig. S5). Thyroglobulin, the reference protein with the highest molecular mass (669 kDa), was found in fractions 7–10, indicating that proteins, complexes, or aggregates that can be found in higher (and thus denser) fractions (fractions 11–14) must have molecular masses in the megadalton range or larger.

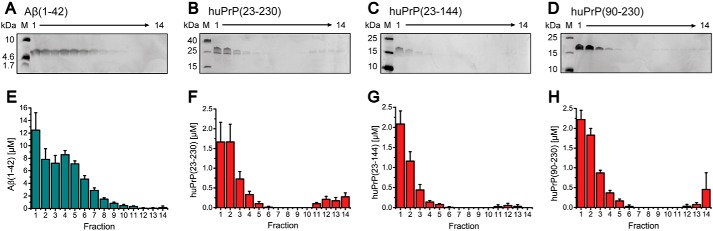

Initially, Aβ(1–42)oligo and huPrP were separately analyzed by sucrose DGC. Either 80 μm of preincubated Aβ(1–42) or a 10 or 20 μm concentration of the respective huPrP protein construct was applied on a sucrose gradient and centrifuged for 3 h. Silver-stained Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels as well as RP-HPLC quantification of all gradient fractions revealed the distribution of the proteins among the fractions and hence among different assembly states (Figs. 3 and S6A). The preincubated Aβ(1–42) sample showed a broad distribution of Aβ(1–42) within the sucrose gradient (Fig. 3, A and E), containing mainly Aβ(1–42)oligo (fractions 3–7) as well as residual monomeric Aβ(1–42) (fractions 1 and 2) as we have established previously (25). The highest concentrations of huPrP(23–230), huPrP(23–144), huPrP(90–230), and huPrP(121–230) were found in fractions 1–3, confirming that huPrP occurs predominantly in a soluble monomeric state. In addition, minor amounts of huPrP were present in fractions 4–6 and 11–14, the latter representing high-molecular-weight aggregates. AFM and CD spectroscopy (Fig. 2) suggest that these were nonfibrillar, amorphous aggregates.

Figure 3.

Distribution of incubated Aβ(1–42) (A and E), huPrP(23–230) (B and F), huPrP(23–144) (C and G), and huPrP(90–230) (D and H) after sucrose DGC. Silver-stained Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels (A–D) and corresponding histograms after RP-HPLC analysis (E–H) are shown. In every image, fractions are shown from left to right corresponding to the fractions from top to bottom of the gradient. Aβ(1–42) can be found in fractions 1–10 (A and E) with fractions 3–7 being the main Aβ(1–42)oligo-containing fractions. All huPrP constructs are mainly detected in fractions 1–3, but low concentrations can also be found in fractions 11–14, especially in the case of huPrP(23–230). Experiments are done in replicates of n = 5 (E), n = 4 (F), n = 6 (G), and n = 4 (H). Error bars represent S.D.

Aβ(1–42)oligo forms high-molecular-weight heteroassemblies with huPrP(23–230) as well as with huPrP(23–144)

After confirmation of the soluble, nonfibrillar state of all huPrP constructs as well as the size distribution of preincubated Aβ(1–42), we analyzed the effect of huPrP binding on the size distribution of Aβ(1–42)oligo. Aβ(1–42), preincubated to form Aβ(1–42)oligo, was added to full-length huPrP(23–230) to yield samples with final concentrations of 80 μm Aβ(1–42) and 2, 5, 10, or 20 μm huPrP(23–230) (concentrations refer to the samples before separation by sucrose DGC).

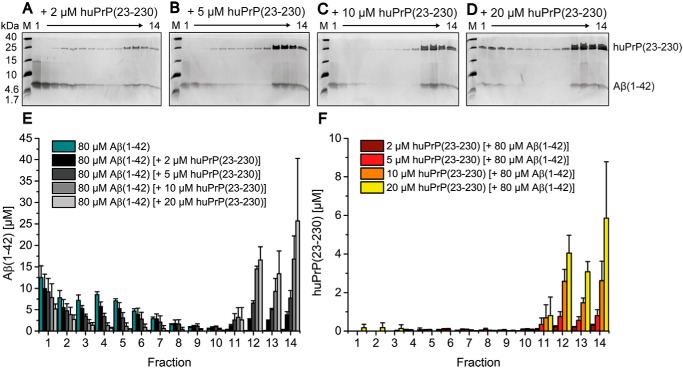

After DGC, each fraction was qualitatively analyzed by SDS-PAGE as well as quantitatively analyzed by RP-HPLC with respect to the Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–230) contents (Fig. 4). The increase of the applied concentration of huPrP(23–230) correlated with the decrease of the concentration of Aβ(1–42) in fractions 3–7 along with the increase of Aβ(1–42) concentration in fractions 11–14. For example, upon addition of 20 μm huPrP(23–230), the average Aβ(1–42) concentration fell from 6 to 0.3 μm in fractions 4–7 but rose from 0.1 to 15 μm in fractions 11–14 (Fig. 4). huPrP(23–230) was mainly detected in fractions 11–14 (see below). This clearly confirms direct interaction between huPrP(23–230) and Aβ(1–42)oligo. huPrP(23–230) interaction was preferential with Aβ(1–42)oligo as the concentration of Aβ(1–42) monomers in fractions 1 and 2 decreased only slightly with increasing huPrP(23–230) concentration. Moreover, instead of simply forming one-to-one complexes, which would be found not far away from fractions 3–7, huPrP(23–230) and Aβ(1–42)oligo form large supramolecular heteroassemblies, which are located in fractions 11–14 and hence have molecular masses in or above the megadalton range (according to the calibration of the density gradient; Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

Formation of heteroassemblies of Aβ(1–42)oligo and huPrP(23–230). Silver-stained Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels after application of 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42) with varying huPrP(23–230) concentrations onto a sucrose gradient (A–D) and corresponding histograms after RP-HPLC analysis (E and F) show the distribution of Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–230). With increasing applied huPrP(23–230) concentrations, Aβ(1–42)oligo (fractions 3–7 in E) decreases. Moreover, both Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–230) appear in fractions 11–14 (bottom of the gradient). Concentrations of Aβ(1–42) in each gradient fraction according to the applied huPrP(23–230) concentration are shown in E, and concentrations of huPrP(23–230) are shown in F. Experiments are done in replicates of n = 3 for all huPrP(23–230) concentrations applied. Error bars represent S.D.

In the absence of Aβ(1–42), huPrP(23–230) appeared in fractions 1–4 (Fig. 3, B and F). In contrast, in samples containing 10 or 20 μm huPrP(23–230) and 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42), the vast majority of huPrP(23–230) was observed in fractions 11–14 (Fig. 4, C, D, and F), indicative of heteroassociation with Aβ(1–42)oligo. Interestingly, at lower huPrP(23–230) concentrations of 2 and 5 μm, faint huPrP(23–230) bands were observed in fractions 4–10. This observation can be explained by an initial formation of smaller Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–230) complexes, potentially of lower density, which convert to larger complexes when increasing the applied huPrP(23–230) concentration (see also Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

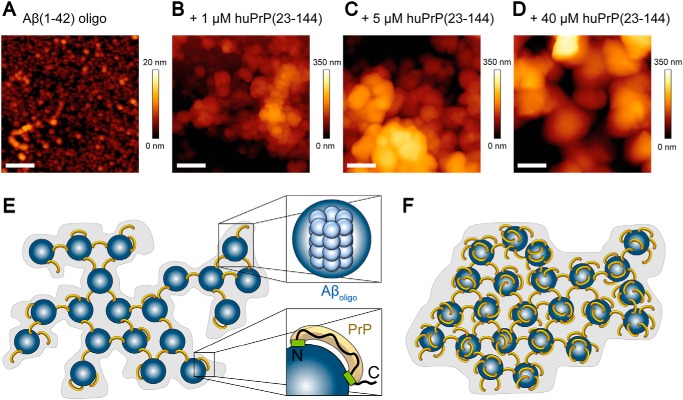

AFM images of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes (A–D) and model of the complexes (E and F). A–D, 1-μm2 AFM images of Aβ oligomers (A) and Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes generated with 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42) and either 1 (B), 5 (C), or 40 μm huPrP(23–144) (D). Scale bars, 200 nm. E and F, model of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP complexes with low (E) and high (F) huPrP content. For clarity, complexes are shown two-dimensional. Aβ(1–42)oligo is shown in blue, huPrP is in yellow, binding sites on huPrP are in green (E, bottom right corner). One Aβ(1–42)oligo is composed of 23 monomers on average (25) (E, top right corner). Based on the ratio of four Aβ (monomer equivalent) to one huPrP in the case of saturation with huPrP, the heteroassemblies contain six huPrP molecules per Aβ(1–42)oligo. The heteroassemblies show many detailed substructures at low huPrP concentrations (E), symbolized by the gray background in the model. After saturation with huPrP, all binding sites on Aβ(1–42)oligo are occupied, leading to compact complexes with smooth surface (D and F).

The quantitative analysis of the DGC fractions by RP-HPLC enabled the determination of the molar ratios between Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–230) within the complexes (Table 1) calculated for every experiment from the total amount of Aβ(1–42) molecules and the total amount of huPrP(23–230) in fractions 11–14. Averaging over fractions 11–14 was necessary as the occurrence of the complexes in the individual fractions can slightly vary between experiments due to the manual fractionation of the gradients. This also explains the larger error bars of Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–230) in the complex-containing fractions 11–14 compared with the error bars in fractions 1–10.

Table 1.

Aβ:huPrP ratios within Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP heteroassemblies

The ratios were calculated for every experiment as the quotient of the total amount of Aβ(1–42) molecules and the total amount of huPrP in fractions 11–14 after sucrose DGC. For the calculation of Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–230) ratios the huPrP(23–230) concentrations in fractions 11–14 found with huPrP(23–230) alone (Fig. 3, B and F) were not considered as they were negligibly small. For concentrations labeled with “ND,” molar ratios were not determined for huPrP(23–230). Comparing the same (huPrP) concentration, similar ratios were obtained for both huPrP(23–144) and huPrP(23–230). Full saturation of the PrP-binding capacity of Aβ(1–42)oligo as evident in the case of 40 μm and 60 μm huPrP(23–144) by the presence of free monomeric huPrP(23–144) (Figs. 5F and S8) resulted in a ratio of about 4 Aβ:1 huPrP(23–144). Experiments were done in replicates of n = 3 for all huPrP(23–230) concentrations applied; for 5, 20, 40, and 60 μm huPrP(23–144) in the presence of 80 μm Aβ(1–42); and for 20 and 60 μm Aβ(1–42) in the presence of 40 μm huPrP(23–144); n = 4 for 40 μm Aβ(1–42) in the presence of 40 μm huPrP(23–144); and n = 5 for 2 and 10 μm huPrP(23–144) in the presence of 80 μm Aβ(1–42). Errors represent S.D.

| Aβ | huPrP | Aβ:huPrP(23–144) | Aβ:huPrP(23–230) |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | ||

| 80 | 2 | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 12.1 ± 1.7 |

| 80 | 5 | 11.3 ± 0.6 | 9.6 ± 2.3 |

| 80 | 10 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 1.7 |

| 80 | 20 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.9 |

| 80 | 40 | 3.93 ± 0.04 | ND |

| 80 | 60 | 4.04 ± 0.08 | ND |

| 60 | 40 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | ND |

| 40 | 40 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | ND |

| 20 | 40 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | ND |

Incubation of Aβ(1–42)oligo with 2 μm huPrP(23–230) led to an Aβ:PrP ratio of 12.1 ± 1.7 within the DGC-purified complexes (Table 1). Application of higher huPrP(23–230) concentrations resulted in the decrease of the Aβ:PrP ratio due to higher huPrP(23–230) content within the heteroassemblies. Incubation of Aβ(1–42)oligo with 20 μm huPrP(23–230) led to an Aβ:PrP ratio of 4.2 ± 0.9. At this applied concentration of huPrP(23–230), it can additionally be found in fractions 1–4 (Fig. 4, D and F), indicating that the PrP-binding capacity of Aβ(1–42)oligo is fully saturated such that an excess of huPrP(23–230) remains monomeric and unbound to Aβ(1–42)oligo. The saturability of the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–230) heteroassociation indicates that it occurs by a defined binding mode and is not just an unspecific coprecipitation of both proteins.

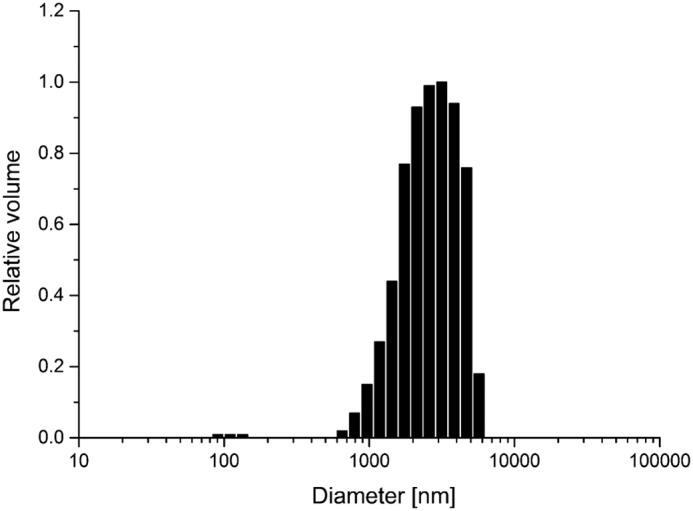

The N-terminal PrP construct huPrP(23–144) shows a similar behavior as the full-length huPrP(23–230) upon interaction with Aβ(1–42)oligo. With increasing huPrP(23–144) concentrations ranging from 2 to 40 μm, Aβ(1–42)oligo in fractions 3–7 disappeared, and higher Aβ(1–42) concentrations were detected in fractions 11–14 (Fig. 5) due to the formation of high-molecular-weight Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes. Formation of assemblies with molecular masses larger than the megadalton range was confirmed by dynamic light scattering (DLS), showing that the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) assemblies mainly have sizes from 0.6 to 6 μm (Fig. 6).

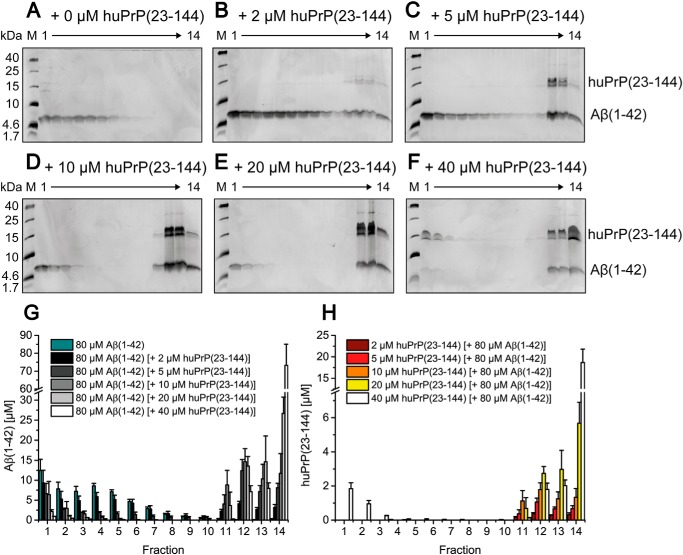

Figure 5.

Formation of heteroassemblies of Aβ(1–42)oligo and huPrP(23–144). Silver-stained Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels after application of 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42) with varying huPrP(23–144) concentrations on a sucrose gradient (A–F) and corresponding histograms after RP-HPLC analysis (G and H) show the distribution of Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–144). With increasing applied huPrP(23–144) concentrations, Aβ(1–42)oligo (fractions 3–7 in G) decreases. Moreover, both Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–144) appear in fractions 11–14 (bottom of the gradient). When 40 μm huPrP(23–144) is added, the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) interaction becomes saturated, reflected by the presence of huPrP(23–144) in fractions 1–3 (F and H). Concentrations of Aβ(1–42) according to the applied huPrP(23–144) concentration are shown in G, and concentrations of huPrP(23–144) are shown in H. In addition to silver staining of Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels, dot-blot analysis detecting either Aβ or huPrP of the DGC fractions after application of 80 μm Aβ(1–42) and 40 μm huPrP(23–144) was performed (Fig. S7), confirming qualitative analyses by silver staining of Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels as well as quantitative RP-HPLC analyses. Experiments are done in replicates of n = 5 (for 2 and 10 μm huPrP(23–144) applied) and n = 3 (for 5, 20, and 40 μm huPrP(23–144) applied). Error bars represent S.D.

Figure 6.

Size distribution of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes measured by dynamic light scattering. The Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) assemblies mainly have sizes in the range from 0.6 to 6 μm.

When huPrP(23–144) was added in final concentrations of 2, 5, 10, and 20 μm, huPrP(23–144) was identified exclusively in fractions 11–14 after DGC. Upon application of 40 μm huPrP(23–144) to Aβ(1–42)oligo, about 10% of the detected huPrP(23–144) was found in fractions 1–4 (Fig. 5, F and H), indicating an excess of huPrP(23–144) and thus a saturation of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes with huPrP(23–144). Although huPrP(23–144) was in excess at the applied concentration of 40 μm (Fig. 5, F and H), there was still some monomeric Aβ(1–42) left in fractions 1 and 2 (Fig. 5, F and G), again confirming that huPrP(23–144) forms complexes only with oligomeric but not with monomeric Aβ(1–42), an observation in full accordance with previous studies (5, 19, 20).

Incubation of Aβ(1–42)oligo with 2 μm huPrP(23–144) resulted in an Aβ:PrP ratio of 10.1 ± 0.8 in the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes (Table 1). Increasing the applied huPrP(23–144) concentration to 40 μm progressively lowered the Aβ:PrP ratio down to a value of 3.93 ± 0.04. Further increase of the applied huPrP(23–144) concentration to 60 μm (Fig. S8) did not further decrease the Aβ:PrP ratio (4.04 ± 0.08; Table 1) in the high-molecular-weight complexes, in agreement with the Aβ:PrP ratio of ∼4 observed when an excess of huPrP(23–230) was applied. This indicates that four Aβ units are required to form one PrP-binding site. The similar behavior of huPrP(23–144) and huPrP(23–230) with respect to Aβ(1–42)oligo binding suggests that huPrP(23–144) contains all epitopes required for binding to Aβ(1–42)oligo, in line with previous findings of other groups (5, 19–22).

We verified that the Aβ:PrP ratio of ∼4 is constant when Aβ(1–42)oligo is saturated with huPrP by adding different final Aβ(1–42)oligo concentrations of 20, 40, 60, and 80 μm to a saturating concentration (40 μm) of huPrP(23–144). At all Aβ(1–42)oligo concentrations, the Aβ:PrP ratio in the heteroassociates was ∼4 with deviations within the experimental error (Table 1).

Deletion of the huPrP N terminus impairs Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP heteroassociation

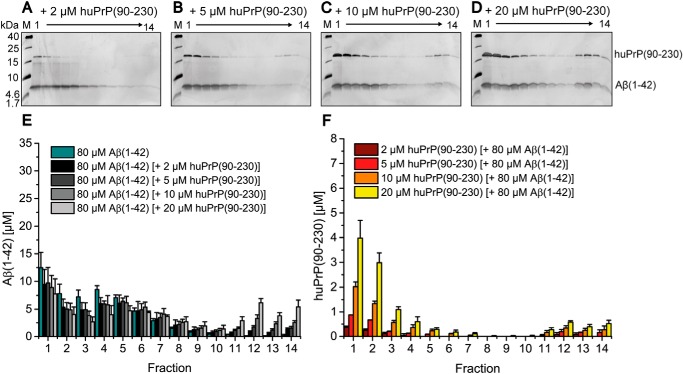

Besides the N-terminal huPrP(23–144) and full-length huPrP(23–230), we further analyzed the C-terminal PrP constructs huPrP(90–230) and huPrP(121–230), which lack the proposed Aβ-binding site at positions 23–27 and, in the case of huPrP(121–230), the proposed binding site at positions ∼95–110 (see Fig. 1A). At all applied concentrations of huPrP(90–230), ranging from 2 to 20 μm, the protein concentrations detected in fractions 11–14 were only slightly elevated (Fig. 7). Even in the presence of 20 μm huPrP(90–230), the majority of Aβ(1–42)oligo was still present in fractions 3–7. The majority of huPrP(90–230) was found in fractions 1–4 at all applied huPrP(90–230) concentrations, similar to the distribution of huPrP(90–230) without Aβ(1–42)oligo (Fig. 3, D and H). When 20 μm huPrP(90–230) was applied to Aβ(1–42)oligo, only about 15% of huPrP(90–230) was found in fractions 11–14. This is in contrast to the observations that, when 20 μm huPrP(23–230) or huPrP(23–144) was applied to Aβ(1–42)oligo, about 96% of huPrP(23–230) or 100% of huPrP(23–144), respectively, were found in these fractions. Therefore, compared with huPrP(23–230) (Fig. 4) and huPrP(23–144) (Fig. 5), huPrP(90–230) (Fig. 7) is almost incapable of forming high-molecular-weight Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP complexes. This is in full agreement with previous studies that demonstrated the importance of both Aβ(1–42)oligo-binding sites on PrP (19–22).

Figure 7.

Impaired formation of heteroassemblies of Aβ(1–42)oligo and huPrP(90–230). Silver-stained Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels after application of 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42) with varying huPrP(90–230) concentrations on a sucrose gradient (A–D) and corresponding histograms after RP-HPLC analysis (E and F) show the distribution of Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(90–230). With increasing applied huPrP(90–230) concentrations, just slightly increased protein concentrations of both Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(90–230) are found in bottom fractions 11–14. Concentrations of Aβ(1–42) according to the applied huPrP(90–230) concentration are shown in E, and concentrations of huPrP(90–230) are shown in F. Experiments are done in replicates of n = 3 for all huPrP(90–230) concentrations applied. Error bars represent S.D.

When 20 μm huPrP(121–230) was applied to Aβ(1–42)oligo, even less Aβ(1–42) and huPrP were found in fractions 11–14 than in the case of huPrP(90–230) (Fig. S6, B and C). This demonstrates that the proposed binding site at positions ∼95–110, although on its own not sufficient for high-affinity interaction, does contribute to Aβ(1–42)oligo binding.

The morphology of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) heteroassemblies depends on the huPrP concentration

For structural characterization of the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP complexes, we focused on the N-terminal huPrP(23–144) construct as the PrP C terminus is not required for complex formation. Heteroassemblies formed in the presence of different huPrP(23–144) concentrations ranging from 1 to 40 μm were analyzed by AFM. Unbound Aβ(1–42) or huPrP(23–144) was removed by centrifugation and repeated washing steps followed by imaging of the heteroassemblies on mica in air using intermittent contact mode. Imaging was particularly challenging because the assemblies were several micrometers high with deep holes and high stickiness, which led to rapid contamination of cantilever tips. To display the different features of the samples in more detail, images were taken of the outer surfaces of the heteroassemblies (Fig. 8) several hundred nanometers above the mica support.

For complexes prepared from 80 μm Aβ(1–42) and 1 μm huPrP(23–144) (Fig. 8B), we observed loose clusters of irregular spheres or globules, which again exhibited globular substructures. The clusters typically measured about 200 nm in height and up to 2.5 μm in width with substructures of 20–70 nm in height. Because of the curvature of the surfaces, only a crude estimate of the size of these heteroassemblies and their substructures was possible due to their clustering.

Heteroassemblies prepared at an increased huPrP(23–144) concentration of 5 μm (Fig. 8C) were up to 500 nm high and had a more compact appearance, suggesting a tighter interaction between the subassemblies. The surface of the globular subassemblies seemed to be smoother in this case. When the huPrP(23–144) concentration for heteroassociation was further raised to 40 μm (Fig. 8D), the resulting heteroassemblies were up to 1 μm high, exhibiting globular subassemblies with smooth surface appearance and unresolved substructure. In all cases, Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) heteroassemblies (Figs. 8, B–D) were much larger than Aβ(1–42)oligo (Fig. 8A), demonstrating that the heteroassemblies contain multiple copies of Aβ(1–42)oligo.

We have previously shown that an average Aβ(1–42)oligo consists of about 23 monomeric units (25). Combining this finding with the Aβ:PrP ratios determined here, the heteroassemblies contain approximately six huPrP(23–230) or huPrP(23–144) molecules on average per Aβ(1–42)oligo in the presence of an excess of huPrP. Therefore, a simplified model of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP assemblies can be drawn (Fig. 8, E and F). This model also considers the potential of huPrP to cross-link Aβ(1–42)oligo via its two basic N-terminal binding sites (residues 23–27 and ∼95–110), which of course cannot be formed by huPrP(90–230) or huPrP(121–230). Such cross-links may play a crucial role in Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP assembly due to the multivalent presentation of epitopes on Aβ(1–42)oligo.

At low concentrations of huPrP(23–144), the huPrP-binding sites on Aβ(1–42)oligo are only partially occupied (Fig. 8E), leading to moderate assembly of Aβ(1–42)oligo, presumably promoted by charge neutralization and huPrP-induced cross-linking. This is in line with the loose appearance of heteroassemblies in AFM (Fig. 8B). At high concentrations of huPrP(23–144), the huPrP-binding sites on Aβ(1–42)oligo are fully occupied (Fig. 8F), resulting in saturated Aβ(1–42)oligo assembly, in agreement with the compact appearance of heteroassemblies in AFM (Fig. 8D).

The d-enantiomeric peptide RD2D3-FITC competes with huPrP for binding to Aβ(1–42)oligo

Soluble N-terminal PrP fragments, including the naturally produced neuroprotective N1 fragment, block neurotoxic effects of soluble oligomers (20, 23, 24), presumably by competing with membrane-anchored PrPC for Aβoligo. In line with this, we found that huPrP(23–144) rescues the viability of PC-12 cells from Aβ(1–42)oligo-induced toxicity in a concentration-dependent manner according to the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) cell viability test (Fig. S9). Compounds that compete with membrane-anchored PrPC for Aβoligo in a similar fashion might therefore be of therapeutic interest. Similarly to huPrP, our well characterized Aβ-binding d-peptides form heteroassemblies with Aβ(1–42)oligo (28). These specific d-peptides contain a high ratio of basic amino acid residues and are in that respect similar to the Aβ(1–42)oligo-binding sites within the PrP N terminus (5, 19–22). Similar to the soluble N-terminal PrP fragment huPrP(23–144), the d-peptide RD2D3 shows rescue of PC-12 cell viability from Aβ(1–42)oligo-induced toxicity in the MTT test (Fig. S9 and Ref. 30). Therefore, the d-peptides might act by a similar mechanism as N-terminal huPrP fragments, i.e. competition with membrane-anchored PrPC for Aβoligo. To investigate this hypothesis, we analyzed the effect of the d-peptide RD2D3, labeled with a fluorescent dye (FITC), on the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) interaction.

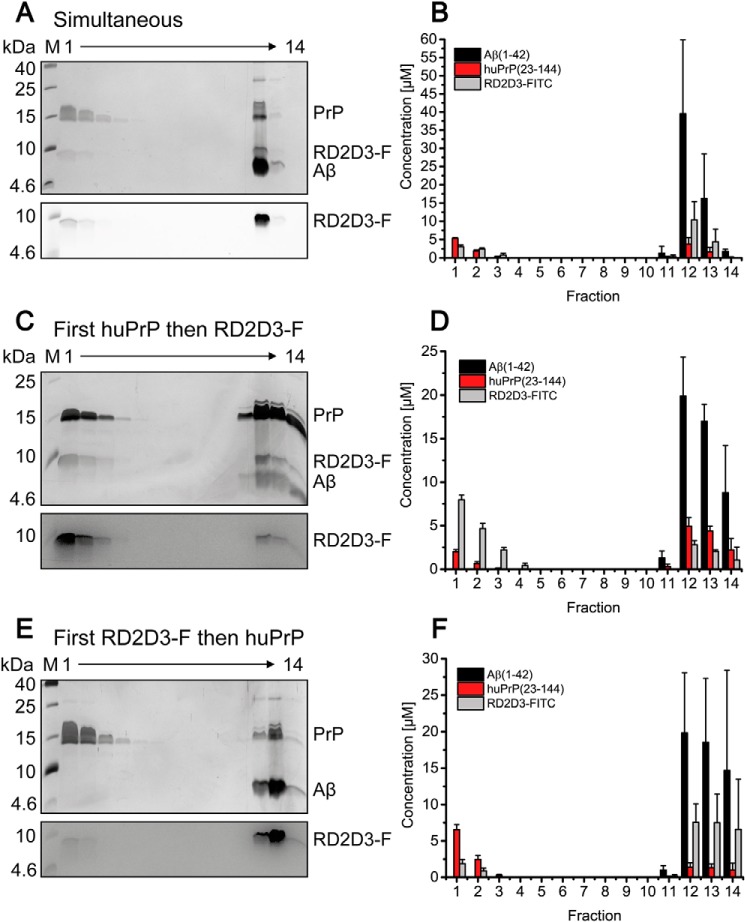

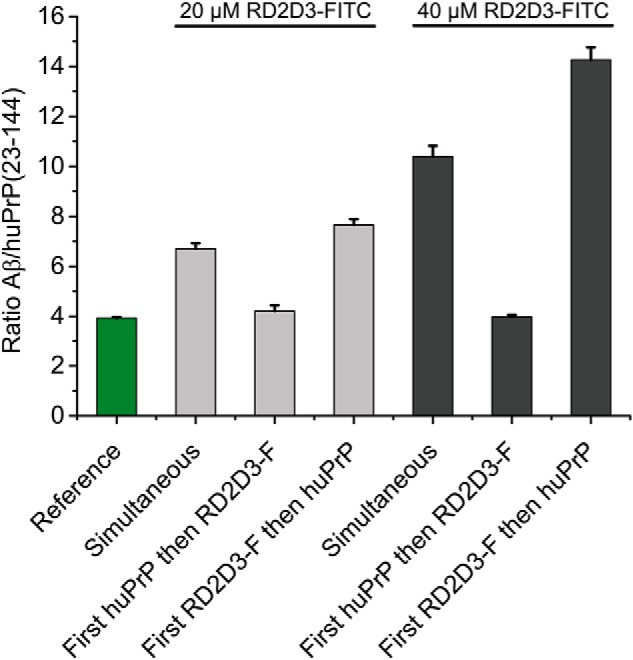

Determination of Aβ:PrP ratios within the heteroassemblies might be a suitable approach to identify potential drug candidates that interfere with the Aβ–huPrP interaction. If a compound competes with huPrP(23–144) for Aβ(1–42)oligo, the Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–144) ratio within the complexes will change to higher values due to decreased huPrP(23–144) binding to Aβ(1–42)oligo.

First, we verified that huPrP(23–144) and RD2D3-FITC do not form high-molecular-weight complexes with each other (Fig. S10). For studying the effect of RD2D3-FITC, constant final concentrations of 80 μm Aβ(1–42) and 40 μm huPrP(23–144) in the samples applied to DGC were chosen. Under these conditions, in the absence of RD2D3-FITC, the PrP-binding capacity of Aβ(1–42)oligo is fully exploited, resulting in an Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–144) ratio of 4:1 in the heteroassemblies (Table 1) and a slight excess of huPrP(23–144) that remains monomeric (Fig. 5). The Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–144) ratio of 4:1 was set as reference for the analysis of potential effects of RD2D3-FITC on the Aβ–huPrP interaction. We compared the effect of different orders of application of RD2D3-FITC or huPrP(23–144) to the sample. Either RD2D3-FITC or huPrP(23–144) was preincubated with Aβ(1–42), and the other compound was applied after 2 h for a further 30 min. Alternatively, Aβ(1–42)oligo was preformed, and RD2D3-FITC and huPrP(23–144) were mixed and simultaneously applied to Aβ(1–42)oligo for a further 30 min. When 40 μm RD2D3-FITC was applied after preincubation of huPrP(23–144) with Aβ(1–42)oligo (Fig. 9, C and D), the majority of RD2D3-FITC was located in fractions 1–3 after DGC. Although low concentrations of RD2D3-FITC were found in the fractions containing heteroassemblies (fractions 11–14), the Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–144) ratio remained at 4:1 as in the reference (Fig. 10). The preincubation of 40 μm RD2D3-FITC with Aβ(1–42) before huPrP(23–144) application (Fig. 9, E and F), however, resulted in a drastic decrease of huPrP(23–144) bound in the heteroassemblies and an increase of RD2D3-FITC in fractions 11–14. At the same time, the Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–144) ratio changed to 14.3 ± 0.5 (Fig. 10). huPrP(23–144) was mainly found in fractions 1–3, in agreement with a monomeric, unbound state. Simultaneous application of huPrP(23–144) and RD2D3-FITC to Aβ(1–42)oligo resulted in an intermediate outcome (Fig. 9, A and B). Here, the Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–144) ratio was 10.4 ± 0.4, which is significantly increased compared with the ratio for early huPrP(23–144) application but lower than that for early RD2D3-FITC application. Reduction of the RD2D3-FITC concentration from 40 to 20 μm (Figs. 10 and S11) resulted in the same tendency with respect to the ratios and the protein distributions within the gradient and reduced Aβ(1–42):huPrP(23–144) ratios due to the decreased d-peptide concentration. These results demonstrate the competition between huPrP(23–144) and RD2D3-FITC for Aβ(1–42)oligo. The degree of competition of RD2D3-FITC depended on the concentration as well as on the order of RD2D3-FITC and huPrP(23–144) application.

Figure 9.

Interference of the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) interaction by RD2D3-FITC. Shown is the distribution of 80 μm Aβ(1–42), 40 μm huPrP(23–144), and 40 μm RD2D3-FITC after sucrose DGC for different orders of RD2D3-FITC and huPrP(23–144) addition. A, C, and E, Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–144) distributions in silver-stained Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE gels and the distribution of RD2D3-FITC after fluorescence detection on the same gels are shown. B, D, and F, quantification by RP-HPLC of each component. Either huPrP(23–144) and RD2D3-FITC were simultaneously added to Aβ(1–42)oligo (A and B), huPrP(23–144) was preincubated with Aβ before RD2D3-FITC addition (C and D), or RD2D3-FITC was preincubated with Aβ before huPrP(23–144) addition (E and F). Dependent on the order of application of RD2D3-FITC or huPrP(23–144) to the sample, the distributions of huPrP(23–144) and RD2D3-FITC change. Experiments were done in replicates of n = 3 for all orders of application of RD2D3-FITC or huPrP(23–144) to the sample. Error bars represent S.D.

Figure 10.

Altered Aβ:huPrP(23–144) ratios within Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) assemblies show the interference by RD2D3-FITC. For all experiments, constant concentrations of 80 μm Aβ(1–42) and 40 μm huPrP(23–144) were used. The reference of 3.93 ± 0.04 Aβ:huPrP(23–144) results from data obtained in the absence of RD2D3-FITC (Table 1). The strongest interference of RD2D3-FITC with the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) interaction was observed at the higher RD2D3-FITC concentration (40 μm) when RD2D3-FITC was preincubated with Aβ before addition of huPrP(23–144). Experiments were done in replicates of n = 3 for all orders of application of RD2D3-FITC or huPrP(23–144) to the sample. Error bars represent S.D.

Discussion

In 2009, Laurén et al. (5) reported that oligomeric Aβ binds to membrane-anchored PrPC, leading to toxic signaling across the cell membrane. Although subsequent studies questioned the role of PrPC in toxic signaling (7, 49–51), further evidence was gained in support of the original findings (5, 12, 13, 20). According to the current view of PrPC–Aβoligo-induced signaling, metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 interacts with PrPC and activates the intracellular Fyn kinase when Aβ oligomers are bound to membrane-anchored PrPC (12, 13). This activation leads to hyperphosphorylation of tau protein as well as to phosphorylation of NMDA receptors, two mechanisms that finally lead to neuronal damage (12, 14, 15, 17). The elucidation of these mechanisms has opened new strategies to prevent toxic signaling in AD by targeting one of these proteins or mediators.

The Aβ(1–42)oligo–PrP interaction is at the core of the PrP-mediated toxic signaling cascade. Here, we have characterized the Aβ(1–42)oligo–PrP interaction by applying a set of soluble huPrP constructs and by taking advantage of the QIAD assay (25), which enables determination of the size distribution of Aβ assembly species and their complexes based on separation by DGC. We found that Aβ(1–42)oligo and huPrP readily associate to form heteroassemblies above the megadalton range (Figs. 4–6 and 8). The heteroassemblies were imaged by AFM as μm-sized clusters of nm-sized globular substructures (Fig. 8).

Heteroassociation is greatly impaired for the huPrP variants devoid of the N terminus, huPrP(90–230) and huPrP(121–230) (Figs. 7 and S6), in agreement with the notion that both Aβ-binding sites in the huPrP N terminus (residues 23–27 and ∼95–110 (5, 19–22)) are required for high-affinity interaction. This is in line with recent reports showing that the effect of soluble, anchorless PrP(90–231) with respect to prevention of Aβ-mediated cytotoxicity was substantially weaker compared with full-length huPrP or N-terminal huPrP (52). In addition, Nieznanski et al. (23) showed that about 10-fold higher concentrations of huPrP(90–231) than of huPrP(23–231) or huPrP(23–144) were required to achieve comparable inhibitory effects on Aβ(1–42) fibril formation. Similarly, a complete loss of binding capacity to Aβ(1–42)oligo after deletion of the N-terminal region 23–89 was observed (19). The Aβ-binding sites in huPrP constitute positively charged patches, suggesting that an electrostatic component may promote the interaction. In this context, it is worth noting that the presence of negatively charged patches on Aβ(1–42)oligo has been inferred from engineering of Aβ(1–42)oligo-binding proteins (53).

Further distinctive features of the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP heteroassociation comprise (i) disordered conformation of the binding sites in free PrP, (ii) multivalency (an average Aβ(1–42)oligo can interact with six huPrP molecules), and (iii) a stoichiometry that is not fixed but constrained to a relatively narrow window (the Aβ:PrP ratio is in the range of 4:1–12:1). We searched the literature for protein–protein interactions with similar characteristics and found two notable cases, the interaction of nucleophosmin with nucleophosmin-binding proteins (54) and heteroprotein coacervation of β-lactoglobulin and lactoferrin (55, 56). The interaction of nucleophosmin with binding proteins containing arginine-rich linear motifs is involved in nucleolus formation by liquid-liquid phase separation. The interaction features an electrostatic component, intrinsic disorder in the free binding motifs, as well as multivalency: acidic oligomers of nucleophosmin interact with proteins that contain at least two basic linear motifs (54). Heteroprotein coacervation of β-lactoglobulin and lactoferrin features a constrained stoichiometry with some variation depending on the molar ratio of the initial mixture (55, 56).

The molar ratios in the Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP heteroassemblies suggest that an average Aβ(1–42)oligo can directly interact with up to six huPrP molecules. This multivalent interaction, established here for soluble huPrP constructs, may also have consequences for GPI-anchored PrPC. For example, clustering of PrPC can promote the activation of Fyn kinase (57, 58). Moreover, the multivalency of Aβ(1–42)oligo may contribute to the formation of ternary complexes with other membrane receptors (59). N1, a secreted, soluble N-terminal fragment resulting from α-cleavage of huPrP, comprises both Aβ(1–42)oligo-binding sites and is therefore primed for heteroassociation with Aβ(1–42)oligo. Intriguingly, N1 is neuroprotective, inhibits Aβ(1–42)oligo-mediated neurotoxicity (20), and forms coaggregates with Aβ that have been detected in post-mortem brain tissue (60).

As the Aβ–PrP interaction might be a possible therapeutic target in treating Alzheimer's disease, there is great effort to identify either Aβ- or PrP-binding compounds that inhibit the Aβ–PrPC interaction. For example, dextran sulfate sodium (61) and Chicago Sky Blue 6B (62) inhibit binding of Aβ(1–42)oligo to PrP. Similarly, anti-PrP antibodies blocked oligomeric Aβ binding to PrP and prevented Aβ oligomer–induced neurotoxicity (5, 63–65). The QIAD assay in its version introduced here, permitting simultaneous quantification of Aβ(1–42), huPrP, and compound, allows identification and characterization of a compound's interference with the Aβ–PrP interaction. We found that the Aβ:PrP ratio in the heteroassociates (Fig. 10) is a suitable indicator of a compound's competition with PrP for Aβ(1–42)oligo.

We have previously identified a number of d-enantiomeric peptides as promising drugs that eliminate Aβ(1–42)oligo and improve cognition in transgenic AD mice (25–27, 66). Here, we have observed that the d-peptide RD2D3 interferes with the binding of huPrP(23–144) to Aβ(1–42)oligo. As a rescue of cell viability of Aβ-treated cells (Fig. S9 and Ref. 30) and enhancement of cognition (39) were shown for RD2D3, our studies suggest that interference with the Aβ–PrP interaction might be one potential mechanism of action of this class of d-peptides.

Experimental procedures

Purification of huPrP

All huPrP constructs, huPrP(23–230), huPrP(23–144), huPrP(90–230), and huPrP(121–230), were generated recombinantly in E. coli. huPrP(23–230) and huPrP(90–230) were cloned in pET-11a vectors and transformed in Rosetta 2 (DE3) as described by Luers et al. (67). Both constructs contain the natural polymorphism Met-129. Before induction, E. coli was grown in terrific broth medium at 37 °C and 160 rpm shaking. At an OD600 of 0.7, recombinant protein expression was induced by adding 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and the growth temperature was lowered to 25 °C. Cells were harvested after overnight expression. For the preparation of isotope-labeled [U-15N]huPrP(23–230) or [U-13C,15N]huPrP(23–230), M9 minimal medium containing the desired isotopes was used. The purification is based on the protocol of Mehlhorn et al. (68). Harvested cells were washed with 1× PBS buffer for 30 min, harvested again, and resuspended in 3 ml of digestion buffer (1× PBS, 20 mm MgCl2, DNase I containing protease inhibitor mixture (Complete EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science, one tablet/100 ml)) per gram of cells and stored at −20 °C. The cells were disrupted at 1.2 kbar in a cell disruption system (Constant Systems), and the lysate was centrifuged at 28,700 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The insoluble inclusion bodies were dissolved in about 10 ml of 6 m guanidinium HCl, 5 mm DTT, 12.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and centrifuged again (see above). The supernatant was separated by size exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 preparative grade column. Analytical samples of every second elution fraction were precipitated with 20% (w/v) TCA to remove the guanidinium HCl and investigated by SDS-PAGE. huPrP(23–230)- or huPrP(90–230)-containing fractions were pooled and purified by RP-HPLC. A semipreparative C8 column (Zorbax 300 SB-C8 semipreparative, 9.4 × 250 mm, Agilent) allowed the separation of huPrPs from impurities using a 20–30% (v/v) gradient of acetonitrile + 0.1% (v/v) TFA within 15 min followed by a 10-min step of isocratic 30% (v/v) acetonitrile + 0.1% (v/v) TFA. The purifications were performed at 80 °C at a flow rate of 4 ml/min. The elution fractions containing huPrP were pooled, dried by lyophilization, finally dissolved in Milli-Q water and adjusted to concentrations ranging from 96 to 140 μm. Stocks of 100–200 μl were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. We chose water for the preparation of the huPrP stock solutions as huPrP is highly soluble in water.

huPrP(23–144) was cloned in a pET302/NT-His vector and transformed in E. coli BL21(DE3). This huPrP construct also contains the natural polymorphism Met-129. Cells were grown in LB medium at 37 °C and 160 rpm shaking and incubated overnight after induction at these conditions. For the preparation of isotope-labeled [U-15N]huPrP(23–144) or [U-13C,15N]huPrP(23–144), M9 minimal medium containing the desired isotopes was used. Resuspension and disruption of the cells were performed as described above. The insoluble inclusion bodies were dissolved in 10 ml of 6 m guanidinium HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and centrifuged (see above). The supernatant was separated by IMAC with two serially connected 5-ml Protino nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid columns (Macherey-Nagel). A washing step with 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, allowed the removal of the denaturing agent guanidinium HCl. The elution occurred with a linear gradient from 0 to 500 mm imidazole, 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. The huPrP(23–144)-containing fractions (verified by SDS-PAGE) were pooled, and the hexahistidine tag was cleaved by tobacco etch virus protease. RP-HPLC purification, lyophilization, and storage of the protein were performed as described above.

The expression plasmid for huPrP(121–230) was obtained from Dr. Werner Kremer, University of Regensburg. As described previously (47), it was cloned in pRSET A vector with an N-terminal histidine tail and thrombin cleavage site. The plasmid was transformed in Rosetta 2 (DE3). Before induction, E. coli was grown in 2YT medium (3.5% Tryptone, 2% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl) at 37 °C and 160 rpm shaking. At an OD600 of 0.6, recombinant protein expression was induced by adding 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and the growth temperature was lowered to 22 °C for overnight expression. After harvesting and washing the cells twice with 5 mm EDTA, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, they were resuspended in 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. After addition of 0.1 mg/ml DNase and 15 mm MgCl2 and incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, they were sonicated on ice five times for 1 min (Bandelin Sonopuls, sonotrode VS 70 T, 60% amplitude).

The insoluble inclusion bodies were harvested by centrifugation (see above); washed with 5 mm EDTA, 12.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; and dissolved in 8 m guanidinium HCl, 12.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, at 4 °C. After 1-h centrifugation (see above), the supernatant was separated by IMAC with two serially connected 5-ml Protino nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid columns. The elution of the hexahistidine-tagged PrP(121–230) occurred with a linear gradient of 500 ml from 0 to 500 mm imidazole in 6 m guanidinium HCl, 12.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

huPrP(121–230)-containing fractions were pooled and purified by RP-HPLC. A semipreparative C8 column (Zorbax 300 SB-C8, 9.4 × 250 mm) allowed the separation of huPrP(121–230) from impurities using a 20–48% (v/v) gradient of acetonitrile + 0.1% (v/v) TFA within 20 min followed by a 10-min step of isocratic 48% (v/v) acetonitrile + 0.1% (v/v) TFA. The purification was performed at 80 °C at a flow rate of 4 ml/min. The elution fractions containing huPrP(121–230) were pooled and dried by lyophilization. Thrombin cleavage of the fusion protein was performed with 2.5 mg/ml fusion protein in 50 mm MES, pH 6.0, with a final concentration of 8 units of thrombin (Serva 36402.02)/mg of protein for 7 days, when nearly 98% of the protein was digested. RP-HPLC purification, lyophilization and storage of the protein were performed as described above.

Preparation of Aβ(1–42) stocks

1 mg of synthetic Aβ(1–42) (Bachem AG) was incubated with 700 μl of hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) overnight. The solution was divided in 36-μg aliquots in LoBind reaction tubes (Eppendorf AG) and lyophilized in a rotational vacuum concentrator system connected to a cold trap (both Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH). The lyophilizates were stored at room temperature.

Standard proteins for DGC calibration

40 μg of the standard proteins ovalbumin, conalbumin, aldolase, apoferritin, and thyroglobulin in 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, from a gel filtration high-molecular-weight calibration kit (GE Healthcare) were analyzed by sucrose DGC (see below) to calibrate the gradient.

Preparation of samples containing Aβ(1–42) and huPrP (any construct)

Preincubation of Aβ(1–42)

For formation of Aβ(1–42)oligo, Aβ(1–42) was incubated at concentrations of typically 81-100 μm to achieve an identical final concentration of 80 μm Aβ after huPrP addition in all samples prepared for DGC. The incubation was performed in 30 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, at 22 °C and 600 rpm shaking for 2 h. This particular incubation time ensures the production of high amounts of Aβ(1–42)oligo without formation of larger aggregates or fibrils that would appear in the bottom fractions of the density gradient and might affect analytics of Aβ–huPrP complexes.

Addition of huPrP

huPrP stock solutions in Milli-Q water were centrifuged directly before use in a TL 100 ultracentrifuge with a TLA-55 rotor (Beckman) for 30 min at 4 °C and 100,000 × g to remove potential aggregates. Final concentrations of 2–60 μm huPrP(23–144), of 20 μm huPrP(121–230), or 2–20 μm of either huPrP(23–230) or huPrP(90–230) were added to the preformed Aβ(1–42)oligo for a further 30 min at 22 °C and 600 rpm shaking. The final volume of each sample was 100 μl. In another set of experiments, the concentration of Aβ(1–42)oligo was varied (20, 40, and 60 μm), and the huPrP(23–144) concentration was set constant to 40 μm.

Preparation of samples containing Aβ(1–42), huPrP(23–144), and RD2D3-FITC

Three different orders of application of RD2D3-FITC and huPrP(23–144) were analyzed.

Mixture of huPrP(23–144) and RD2D3-FITC (simultaneous)

Aβ(1–42)oligo was generated as described under “Preincubation of Aβ(1–42)” above. After 2-h preincubation, huPrP(23–144) and RD2D3-FITC were added simultaneously to yield samples with final concentrations of 40 μm huPrP(23–144), 80 μm Aβ(1–42), and 20 or 40 μm RD2D3-FITC. The samples were incubated for a further 30 min at 22 °C and 600 rpm shaking.

Addition of huPrP(23–144) during Aβ incubation (first huPrP and then RD2D3-FITC)

Aβ preincubation was done as described before but in the presence of 0.5 molar eq of huPrP(23–144). After 2-h preincubation, RD2D3-FITC was added to yield samples with final concentrations of 40 μm huPrP(23–144), 80 μm Aβ(1–42), and 20 or 40 μm RD2D3-FITC. The samples were incubated for a further 30 min at 22 °C and 600 rpm shaking.

Addition of RD2D3-FITC during Aβ incubation (first RD2D3-FITC and then huPrP)

Aβ preincubation was done as described before but in the presence of 0.5 or 0.25 molar eq of RD2D3-FITC. After 2-h preincubation, huPrP(23–144) was added to yield samples with final concentrations of 40 μm huPrP(23–144), 80 μm Aβ(1–42), and 20 or 40 μm RD2D3-FITC. The samples were incubated for a further 30 min at 22 °C and 600 rpm shaking.

DGC and RP-HPLC analysis of the fractions

This method is an adjusted assay based on the QIAD assay described in Brener et al. (25). In our case, not only Aβ(1–42) but also the prion protein (either huPrP(23–230), huPrP(23–144), or huPrP(90–230)) and the d-peptide RD2D3-FITC are quantified. This assay contains the following steps.

DGC

Each 100-μl sample (see “Preparation of samples containing Aβ(1–42) and huPrP (any construct)” or “Preparation of samples containing Aβ(1–42), huPrP(23–144), and RD2D3-FITC”) was applied on a discontinuous 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, buffered sucrose gradient containing the following volumes and sucrose concentrations (from bottom to top): 300 μl of 60% (w/w), 200 μl of 50% (w/w), 200 μl of 25% (w/w), 400 μl of 20% (w/w), 400 μl of 15% (w/w), 150 μl of 10% (w/w), and 150 μl of 5% (w/w). Each gradient was stepwise layered in a 11 × 34-mm polyallomer centrifuge tube. Gradients were centrifuged in a TL 100 ultracentrifuge using a TLS-55 rotor (Beckman) for 3 h at 4 °C and 259,000 × g. The centrifuged gradients were manually fractionated from top to bottom into 13 142-μl fractions. The remaining volume (arithmetically 54 μl) was mixed with 80 μl of 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, forming fraction 14. For all calculations, a dilution factor of 2.48 was included for fraction 14.

RP-HPLC analysis

Each fraction was analyzed by Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE (see below) and RP-HPLC. For the quantification of Aβ(1–42), huPrP (all constructs), and RD2D3-FITC, 20 μl of each fraction was applied on a Zorbax 300 SB-C8 Stable Bond Analytical column, 4.6 × 250 mm (Agilent) and measured with an Agilent 1260 Infinity system. Each compound was separated by a 10–40% (v/v) acetonitrile gradient + 0.1% (v/v) TFA within 25 min at 80 °C and a flow rate of 1 ml/min. These harsh conditions are necessary to ensure the dissociation of the formed complexes, especially in density gradient fractions 11–14. For detection of the substances, the UV absorbance at 214 nm was used. Known concentrations of Aβ(1–42), huPrP (all constructs), as well as RD2D3-FITC and their corresponding plot of peak area versus protein concentration enabled the calibration and finally the calculation of the protein concentrations present in the fractions. The program package ChemStation by Agilent allowed data recording and peak area integration. All histograms were illustrated with OriginPro 9.0.

Determination of Aβ:huPrP ratios

All generated complexes containing Aβ(1–42) and huPrP (and RD2D3-FITC) were verified in gradient fractions 11–14. For the calculation of Aβ: huPrP ratios, Aβ(1–42) and huPrP amounts in fractions 11–14 were summed. Averaging over fractions 11–14 was necessary as the appearance of the complexes can shift a little within the different fractions due to manual fractionation of the gradients. Then Aβ(1–42) amounts were divided by huPrP amounts to get a ratio for each experiment. The mean ± S.D. of the ratios was calculated over all performed experiments.

Verification of the disulfide bond in huPrPs between Cys-179 and Cys-214 by RP-HPLC

To analyze whether purified huPrP(23–230), huPrP(90–230), and huPrP(121–230) under study contain a disulfide bond between Cys-179 and Cys-214 in the fully oxidized state, purified samples of 5 μm protein were reduced overnight with 25 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride in 6 m guanidinium HCl, 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and analyzed by RP-HPLC as described above. Samples treated only with 6 m guanidinium HCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, were used as controls. The reductive opening of the disulfide bond results in a characteristic elongation of the retention time for the reduced state when compared with the oxidized states.

SDS-PAGE and silver staining

Qualitative analysis of the DGC fractions was done by Tris/Tricine SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining. To this end, 15 μl of each fraction was diluted 1:1 in sample buffer (12% glycerol, 4% SDS, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2% β-mercaptoethanol), applied onto 20% Tris/Tricine gels, and subjected to gel electrophoresis at 40 mA/gel. The preparation of the Tris/Tricine gels is based on the protocol by Schägger and von Jagow (69). Gels containing samples with RD2D3-FITC were analyzed by fluorescence detection (excitation, 470 nm; emission, 530 nm) before silver staining. Silver staining of the gels based on the protocol by Heukeshoven and Dernick (70) allowed visualization of protein bands.

Dot-blot analysis

For further qualitative verification of the Aβ(1–42) and huPrP(23–144) contents within DGC fractions, a dot blot was performed. 2 μl of all 14 denatured sucrose DGC fractions was pipetted onto two pieces of Biotrace NT nitrocellulose membrane (Pall) and allowed to air dry. After blocking with 5% milk powder in 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, for 30 min, the membranes were incubated for 15 min with 0.2 μg/ml prion protein mAb Saf32 (Bertin Bioreagent) or 0.6 μg/ml cell culture supernatants of Aβ(1–8)-recognizing IC16 antibody in 5% milk powder, 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6. After three 5-min washes with 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, the membranes were incubated for 15 min with 0.1 μg/ml peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy + light) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) in 5% milk powder, 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6. After three 5-min washes with 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, the immunoreactivity was visualized with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce).

Dynamic light scattering

DLS was performed on a submicron particle sizer, Nicomp 380 (Particle Sizing Systems Nicomp, Santa Barbara, CA). Data were analyzed with the Nicomp algorithm using the volume-weighted Nicomp distribution analysis. The DLS sample of Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) complexes derived from 80 μm Aβ(1–42) and 40 μm PrP(23–144) was prepared by pooling fractions 11–14 after sucrose DGC. For data analysis, a measured refractive index in the sample of 1.409 corresponding to 44.8% sucrose and a viscosity of 9.2 centipoise was taken into account (71).

MTT cell viability assay

MTT-based cell viability assays (37) were performed to investigate the cytotoxicity of 1 μm Aβ(1–42)oligo either in the absence or after mixing and further incubation of Aβ(1–42)oligo with 0.02, 0.1, or 0.5 μm huPrP(23–144) or with 0.2 or 1 μm RD2D3, respectively. Rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells (Leibniz Institute DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 5% horse serum. 10,000 cells/well were seeded on collagen-coated 96-well plates (Gibco, Life Technologies) and incubated in a 95% humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h.

Added Aβ(1–42)oligo, either alone or after mixing and further incubation with huPrP(23–144) or RD2D3, was prepared as described under “Preparation of samples containing Aβ(1–42) and huPrP (any construct).” The prepared stock solutions contained either 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42) alone or 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42) mixed and further incubated with 1.6, 8, or 40 μm huPrP(23–144) or 80 μm preincubated Aβ(1–42) mixed and further incubated with 16 or 80 μm RD2D3.

After further incubation for 24 h in a 95% humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C, cell viability was measured using Cell Proliferation Kit I (MTT) (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The absorbance of the formazan product was determined by measuring at 570 nm after subtracting the absorption at 660 nm in a Polarstar Optima plate reader (BMG LABTECH, Offenburg, Germany). All results were normalized to cells that were treated with buffer only. The arithmetic mean of all 15 measurements per approach was calculated.

AFM

AFM was done using a Nanowizard 3 system (JPK Instruments AG). All samples were prepared as described under “Preparation of samples containing Aβ(1–42) and huPrP (any construct)”. 50 μl of Aβ(1–42)oligo or 25 μl of huPrP(23–144) was incubated on freshly cleaved mica for 3 or 30 min, respectively. Aβ(1–42)oligo–huPrP(23–144) heteroassemblies had to be cleared from unbound Aβ(1–42) or huPrP(23–144) and were therefore centrifuged at 16,100 × g at 4 °C for 30 min and washed twice with 100 μl of 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, respectively. The complexes were then resuspended in 100 μl of 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Then 50 μl of the complexes was incubated for 30 min on freshly cleaved mica. All samples were washed three times with Milli-Q water and dried in a gentle stream of N2.

The samples were measured using intermittent contact mode with a resolution of 512 or 1024 pixels and line rates of 0.5–1 Hz in ambient conditions with a silicon cantilever with nominal spring constant of 26 newtons/m and average tip radius of 7 nm (Olympus OMCL-AC160TS). Due to the differing composition of the megadalton-sized aggregates concerning adhesion, stiffness, and perforation, the imaging parameters (amplitude, set point, and gain) had to be adapted slightly, and the cantilever had to be changed often.

The height images of Aβ(1–42)oligo and huPrP(23–144) were flattened with JPK Data Processing software 5.0.69. The statistics of particle dimensions of Aβ(1–42)oligo were done with Gwyddion 2.44 grain analysis. After plane leveling, grains were marked with a threshold of 13%. The maximum height of the individual grain was corrected with subtraction of the grain minimum.

The lateral size is affected by tip convolution effects (Δ) in AFM images. Considering the nominal radius of rtip = 7 nm of the AFM tip, we corrected the size of the lateral dimension according to Equation 1 for objects below the tip round end as shown in Canet-Ferrer et al. (72). h describes the height of the object.

| (Eq. 1) |

CD spectroscopy

6 μm huPrP(23–230), huPrP(23–144), or huPrP(90–230) in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, was analyzed by CD spectroscopy. Each sample was transferred into a cuvette (110-QS, 1 mm, Hellma Analytics), and spectra from 186 to 280 nm were recorded at a scan speed of 50 nm/min in a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter. Spectra of 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, were used as reference and subtracted from the protein spectra. Ten spectra of each huPrP sample were recorded and accumulated to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Solution NMR spectroscopy

NMR samples of 0.2 mm [U-15N]huPrP(23–230) with 10 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5, in 10% (v/v) D2O and of between 0.11 and 0.36 mm [U-15N]huPrP(23–144) or [U-13C,15N]huPrP(23–144) with different buffers (50 mm, pH ranging from 4.5 to 7.2) in 10% (v/v) D2O were investigated by recording 2D 1H,15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectra (73) at different temperatures ranging from 5.0 to 20.0 °C on a Bruker 600-MHz, Varian 800-MHz, or Varian 900-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with cryogenically cooled triple- or quadruple-resonance probes with z-axis pulsed-field gradient capabilities. The sample temperature was calibrated using methanol-d4 (99.8%) (74). The 1H2O resonance was suppressed by gradient coherence selection with quadrature detection in the indirect 15N dimension achieved by the echo-antiecho method (75, 76). A WALTZ-16 sequence (77) with a field strength of at least 1.1 kHz was used for 15N decoupling during acquisition. At least 927 (128) complex data points were acquired with a spectral width of 16 ppm (26.0 ppm) in the 1H (15N) dimension. All NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe and NMRDraw (78) and analyzed with NMRViewJ (79). 1H chemical shifts were referenced with respect to external 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid in D2O, and 15N chemical shifts were referenced indirectly (80).

Author contributions

N. S. R., L. G., O. B., H. H., W. H., P. N., and D. W. conceptualization; N. S. R., L. G., E. R., W. H., and P. N. formal analysis; N. S. R., L. G., E. R., A. K., O. B., and P. N. investigation; N. S. R., L. G., and E. R. visualization; N. S. R., L. G., E. R., and P. N. methodology; N. S. R., L. G., W. H., P. N., and D. W. writing-original draft; N. S. R., L. G., E. R., A. K., O. B., H. H., W. H., P. N., and D. W. writing-review and editing; L. G., H. H., and D. W. supervision; L. G. and D. W. project administration; H. H. and D. W. resources; D. W. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Dr. Werner Kremer, University of Regensburg, for the expression plasmid for huPrP(121–230); Prof. Dr. Carsten Korth, University of Düsseldorf, for IC16 antibody; Dr. Manuel Etzkorn, University of Düsseldorf, for DLS measurements; and Markus Tusche, Research Centre Jülich, for performance of the MTT assay. We further acknowledge Florian Schmitz and Luis Macorano for technical support. We acknowledge access to the Jülich-Düsseldorf Biomolecular NMR Center.

This work was supported by “Portfolio Technology and Medicine,” the Helmholtz-Validierungsfonds of the Impuls- und Vernetzungs-Fonds der Helmholtzgemeinschaft (to N. S. R. and D. W.), “Portfolio Drug Research” of the Impuls- und Vernetzungs-Fonds der Helmholtzgemeinschaft (to D. W.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB 1208 (to P. N. and D. W.), and European Research Council Consolidator Grant 726368 (to W. H.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S11.

- AD

- Alzheimer's disease

- Aβ

- β-amyloid

- PrP

- prion protein

- Aβoligo

- soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ

- PrPC

- cellular prion protein

- GPI

- glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- PrPSc

- scrapie isoform of PrP

- NMDA

- N-methyl-d-aspartate

- QIAD

- quantitative determination of interference with Aβ aggregate size distribution

- DGC

- density–gradient ultracentrifugation

- RP

- reversed-phase

- huPrP

- human PrP

- AFM

- atomic force microscopy

- IMAC

- immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- DLS

- dynamic light scattering

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

References

- 1. Selkoe D. J., and Hardy J. (2016) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 595–608 10.15252/emmm.201606210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walsh D. M., Klyubin I., Fadeeva J. V., Rowan M. J., and Selkoe D. J. (2002) Amyloid-β oligomers: their production, toxicity and therapeutic inhibition. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30, 552–557 10.1042/bst0300552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walsh D. M., Klyubin I., Fadeeva J. V., Cullen W. K., Anwyl R., Wolfe M. S., Rowan M. J., and Selkoe D. J. (2002) Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416, 535–539 10.1038/416535a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jarosz-Griffiths H. H., Noble E., Rushworth J. V., and Hooper N. M. (2016) Amyloid-β receptors: the good, the bad, and the prion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 3174–3183 10.1074/jbc.R115.702704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laurén J., Gimbel D. A., Nygaard H. B., Gilbert J. W., and Strittmatter S. M. (2009) Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-β oligomers. Nature 457, 1128–1132 10.1038/nature07761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nygaard H. B., and Strittmatter S. M. (2009) Cellular prion protein mediates the toxicity of β-amyloid oligomers. Arch. Neurol. 66, 1325–1328 10.1001/archneurol.2009.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balducci C., Beeg M., Stravalaci M., Bastone A., Sclip A., Biasini E., Tapella L., Colombo L., Manzoni C., Borsello T., Chiesa R., Gobbi M., Salmona M., and Forloni G. (2010) Synthetic amyloid-β oligomers impair long-term memory independently of cellular prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.s 107, 2295–2300 10.1073/pnas.0911829107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Purro S. A., Nicoll A. J., and Collinge J. (2018) Prion protein as a toxic acceptor of amyloid-β oligomers. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 358–368 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salazar S. V., and Strittmatter S. M. (2017) Cellular prion protein as a receptor for amyloid-β oligomers in Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 483, 1143–1147 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dohler F., Sepulveda-Falla D., Krasemann S., Altmeppen H., Schlüter H., Hildebrand D., Zerr I., Matschke J., and Glatzel M. (2014) High molecular mass assemblies of amyloid-β oligomers bind prion protein in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Brain 137, 873–886 10.1093/brain/awt375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prusiner S. B. (1998) Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13363–13383 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Um J. W., Nygaard H. B., Heiss J. K., Kostylev M. A., Stagi M., Vortmeyer A., Wisniewski T., Gunther E. C., and Strittmatter S. M. (2012) Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomer bound to postsynaptic prion protein activates Fyn to impair neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1227–1235 10.1038/nn.3178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Um J. W., Kaufman A. C., Kostylev M., Heiss J. K., Stagi M., Takahashi H., Kerrisk M. E., Vortmeyer A., Wisniewski T., Koleske A. J., Gunther E. C., Nygaard H. B., and Strittmatter S. M. (2013) Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a coreceptor for Alzheimer Aβ oligomer bound to cellular prion protein. Neuron 79, 887–902 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suzuki T., and Okumura-Noji K. (1995) NMDA receptor subunits ϵ1 (NR2A) and ϵ2 (NR2B) are substrates for Fyn in the postsynaptic density fraction isolated from the rat brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 216, 582–588 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakazawa T., Komai S., Tezuka T., Hisatsune C., Umemori H., Semba K., Mishina M., Manabe T., and Yamamoto T. (2001) Characterization of Fyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation sites on GluRϵ2 (NR2B) subunit of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 693–699 10.1074/jbc.M008085200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Tung Y. C., Quinlan M., Wisniewski H. M., and Binder L. I. (1986) Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 4913–4917 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Larson M., Sherman M. A., Amar F., Nuvolone M., Schneider J. A., Bennett D. A., Aguzzi A., and Lesné S. E. (2012) The complex PrPc-Fyn couples human oligomeric Aβ with pathological tau changes in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 32, 16857–16871 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1858-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18. Elezgarai S. R., and Biasini E. (2016) Common therapeutic strategies for prion and Alzheimer's diseases. Biol. Chem. 397, 1115–1124 10.1515/hsz-2016-0190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen S., Yadav S. P., and Surewicz W. K. (2010) Interaction between human prion protein and amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers: role of N-terminal residues. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26377–26383 10.1074/jbc.M110.145516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fluharty B. R., Biasini E., Stravalaci M., Sclip A., Diomede L., Balducci C., La Vitola P., Messa M., Colombo L., Forloni G., Borsello T., Gobbi M., and Harris D. A. (2013) An N-terminal fragment of the prion protein binds to amyloid-β oligomers and inhibits their neurotoxicity in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 7857–7866 10.1074/jbc.M112.423954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kang M., Kim S. Y., An S. S., and Ju Y. R. (2013) Characterizing affinity epitopes between prion protein and β-amyloid using an epitope mapping immunoassay. Exp. Mol. Med. 45, e34 10.1038/emm.2013.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Younan N. D., Sarell C. J., Davies P., Brown D. R., and Viles J. H. (2013) The cellular prion protein traps Alzheimer's Aβ in an oligomeric form and disassembles amyloid fibers. FASEB J. 27, 1847–1858 10.1096/fj.12-222588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nieznanski K., Choi J. K., Chen S., Surewicz K., and Surewicz W. K. (2012) Soluble prion protein inhibits amyloid-β (Aβ) fibrillization and toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33104–33108 10.1074/jbc.C112.400614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Altmeppen H. C., Puig B., Dohler F., Thurm D. K., Falker C., Krasemann S., and Glatzel M. (2012) Proteolytic processing of the prion protein in health and disease. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 1, 15–31 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]