On April 28, 1996, a public mass shooting resulted in the deaths of 35 people in Tasmania, Australia.1 Unlike mass shootings in the United States, this event immediately mobilized the national, state, and territorial governments in Australia. Within 12 days, all eight states and territories had approved the National Firearms Agreement (NFA), which was subsequently implemented in each state and territory within one to two years through legislation and regulations.1 The NFA banned semiautomatic rifles and shotguns, implemented a buy back of the banned weapons, created a licensing and permitting system for the purchase and possession of all firearms, denied licenses to any individual who had committed a violent crime in the past five years, and instituted a 28-day waiting period before the receipt of a new firearm.1

In the months following the public mass shooting on February 14, 2018, that killed 17 students and staff members at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, many state legislatures have considered, and several have enacted, stricter gun legislation. Both supporters and opponents of stricter gun laws are looking toward the Australian experience to promote their policy positions. Supporters point to the sharp declines in firearm homicide and suicide rates in Australia since 1996, whereas opponents argue that the laws had little or no effect.

Given these conflicting positions, the rigorous evaluation of the impact of the Australian NFA by Gilmour et al. (p. 1511) is an important addition to the literature. Their analysis confirmed that there were significant declines in firearm homicides and suicides following the passage of the NFA; however, it also showed that after preexisting declines in firearm death rates and the changes in nonfirearm mortality rates that occurred subsequent to the passage of the agreement were taken into account, there was no statistically observable additional impact of the NFA. The data show a clear pattern of declining firearm homicide and suicide rates, but those declines started in the late 1980s.

INEFFECTIVE STRONG GUN REGULATION?

Does this mean we should conclude that strong gun regulation, such as the type present in Australia, is ineffective in reducing homicide and suicide rates? Not so fast. The critical context for interpreting the Gilmour et al. results is that, even before the NFA, most Australian states and territories had in place relatively strong firearm laws, much stronger than those in the overwhelming majority of US states in 2018.

In 1974, Western Australia issued regulations under the Firearms Act of 1973 that established a permitting system for firearm acquisition or possession and required disclosure of an individual’s criminal history in the application.2 In 1980, South Australia implemented the Firearms Act of 1977, which required an individual to have a permit to possess any firearm, required registration of all firearms, and granted law enforcement officials broad authority (in consultation with a three-person government panel) to deny permit applications.3 In 1990, Queensland enacted a weapons act that required a person to have a license to obtain a firearm, granted law enforcement officials complete discretion to deny a license application, and required that they deny applications to anyone with a conviction for a violent or weapons offense.4

The Australian Capital Territory’s Weapons Act of 1991 required a license to possess any firearm, granted law enforcement officials the authority to deny permits, and required that they deny permits if the applicant had a criminal conviction within the past eight years.5 In 1993, Tasmania implemented the Guns Act of 1991, which created a licensing system for long guns and a permitting system for pistols, in both cases denying gun access to individuals with a history of violent crimes or gun-related offenses.6 Even in New South Wales, which did not enact comprehensive gun regulation until 1996, domestic violence offenders were prohibited from possessing firearms as of 1992.1

It therefore appears that, even before 1996, at least five of Australia’s eight states and territories had gun permitting systems, policies that only seven US states have in place in 2018, 22 years after passage of the NFA. A possible reason that Gilmour et al. did not find any significant effect of the NFA on firearm homicides or suicides is that the primary changes brought about by the agreement (the ban on semiautomatic rifles and the buy-back program) were marginal relative to the permitting systems already in place in some regions, especially after the enactment of legislation in the early 1990s (which, as Gilmour and colleagues point out, followed the adoption of comprehensive gun regulation proposals adopted at the Australian Police Ministers’ Conference in 1991).

It must be recognized that a trend analysis of firearm death rates in Australia before and after passage of the NFA has limited power to detect any true impact of a firearm law that influences not what types of firearms are legal but who has access to those weapons. Banning semiautomatic rifles would not be expected to have a major impact on firearm homicides or suicides because these weapons are not responsible for most firearm deaths and because any firearm—whether considered to be an “assault weapon” or not—is potentially lethal. By contrast, policies that control who has access to guns (i.e., regulations that put in place mechanisms to keep guns out of the hands of people who are at a high risk for violence) are precisely the types of policies that would be most likely to produce measurable effects on firearm-related mortality.

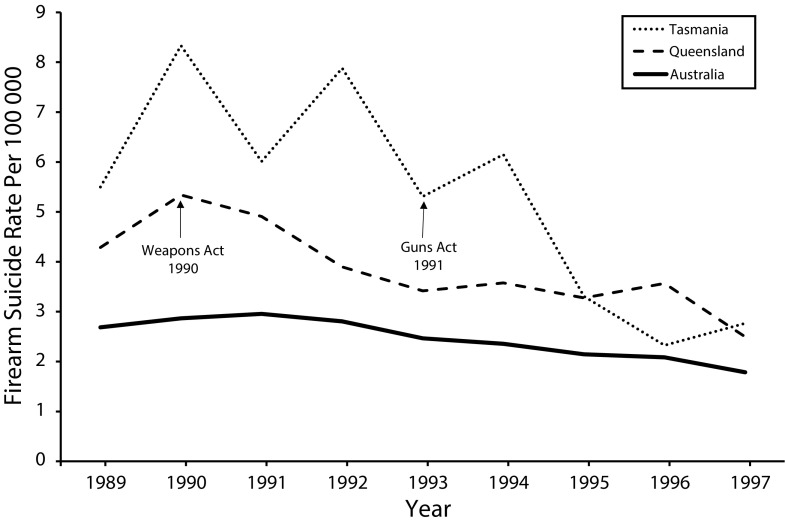

Subsequent research should examine trends in firearm death rates in relation to firearm laws at the state and territorial levels and should investigate potential effects of the comprehensive regulatory systems put in place by many of these governments prior to 1996. A cursory look at firearm suicide trends during the 1990s at the state level (via previously published data7) suggests that these effects could have been substantial (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Trends in Firearm Suicide Rates: Tasmania, Queensland, and Australia as a Whole, 1989–1997

Source. Data were derived from Warner.7

IMPLICATIONS FOR REGULATORY POLICY IN THE UNITED STATES

The Australian experience with firearms regulation has implications for regulatory policy in the United States, but those implications have less to do with the NFA than the fact that even prior to the agreement, most Australian states and territories had enacted legislation that gave law enforcement authorities some control over who could obtain a firearm. The rate of firearm homicides in Australia is dramatically lower than that in the United States not because Australia banned semiautomatic rifles and implemented a buy-back program but because there was a greater degree of control of who had access to firearms even before passage of the NFA. In the two years preceding passage of the agreement, the firearm homicide rate in Australia (approximately 0.4 per 100 000 population7) was already 16 times lower than that in the United States.

We need to understand that in the United States today, law enforcement officials in 40 states have little control over who has access to firearms because they have no discretion over whether they can deny a concealed carry license and no permit is required to obtain a firearm. In 36 of those states, it is not even necessary to undergo a background check when buying a gun from a private seller. The real lesson from the international experience with firearm regulation is that if you have little control over who has access to deadly weapons, you should not be surprised if you have a firearm injury epidemic on your hands.

Footnotes

See also Gilmour et al., p. 1511.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chapman S. Over Our Dead Bodies: Port Arthur and Australia’s Fight for Gun Control. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Sydney University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Government of Western Australia. Firearms regulations, 1974. Available at: https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/statutes.nsf/RedirectURL?OpenAgent&query=mrdoc_22697.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2018.

- 3.Queensland Government, Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel. Weapons Act, 1990. Available at: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/html/inforce/2018-01-01/act-1990-071. Accessed September 5, 2018.

- 4.Government of South Australia. Firearms Act, 1977. Available at: https://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/LZ/C/A/FIREARMS%20ACT%201977/1993.08.31_(1986.10.23)/1977.26.PDF. Accessed September 5, 2018.

- 5.Australian Capital Territory, ACT Parliamentary Counsel. Weapons Act, 1991. Available at: http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/a/1991-8/19911003-4755/pdf/1991-8.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2018.

- 6.Government of Tasmania. Guns Act, 1991. Available at: http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/tas/num_act/ga199134o1991124. Accessed September 5, 2018.

- 7.Warner K. Evaluation of the introduction of Tasmanian firearm control legislation: the Guns Act, 1991. Available at: http://nisat.prio.org/misc/download.ashx?file=36837. Accessed September 5, 2018.