Abstract

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the deadliest event in human history. In 1918–1919, pandemic influenza appeared nearly simultaneously around the globe and caused extraordinary mortality (an estimated 50–100 million deaths) associated with unexpected clinical and epidemiological features. The descendants of the 1918 virus remain today; as endemic influenza viruses, they cause significant mortality each year.

Although the ability to predict influenza pandemics remains no better than it was a century ago, numerous scientific advances provide an important head start in limiting severe disease and death from both current and future influenza viruses: identification and substantial characterization of the natural history and pathogenesis of the 1918 causative virus itself, as well as hundreds of its viral descendants; development of moderately effective vaccines; improved diagnosis and treatment of influenza-associated pneumonia; and effective prevention and control measures.

Remaining challenges include development of vaccines eliciting significantly broader protection (against antigenically different influenza viruses) that can prevent or significantly downregulate viral replication; more complete characterization of natural history and pathogenesis emphasizing the protective role of mucosal immunity; and biomarkers of impending influenza-associated pneumonia.

“O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again.”

—Thomas Wolfe (1900–1938)1

In Wolfe’s classic 1929 novel Look Homeward, Angel,1 the son of a gravestone cutter is haunted by his dead brother’s ghost. Surely, gravestones can speak about people who once walked the earth, of their joys and hopes and hardships, reminding us that they were no different than we who still live. Gravestone inscriptions also reveal the demography and epidemiology of earlier ages, the person, place, and time of life and death. Planted in clusters around the globe exactly a century ago, such gravestones still speak poignantly about the deadliest event in human history,2 the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

One of Countless Gravestones and Monuments Remembering Victims of the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic

Note. Cemetery near the former Lebanon Evangelical Church, 1133 Old Forbes Road, near West Road, Ligonier Township, PA, (gps coordinates 40.234394, -79.177155). The biblical inscription at the bottom refers to Matthew 10:13–16, which discusses Jesus welcoming and blessing little children.

Source. Photographed by David M. Morens, September 6, 2018. Printed with permission.

Look Homeward, Angel, is autobiographical in its depiction of the October 1918 death from influenza pneumonia of Thomas Wolfe’s brother Benjamin Harrison Wolfe (1892–1918), a vivid, medically accurate account of his final agony.1 Benjamin Wolfe was but one of at least 50 million estimated influenza fatalities during that first pandemic year. The mostly forgotten stories of those it struck from life still wait to speak to us, not only from gravestones and books, but also from records, diaries, and fading photographs of victims lying in their deathbeds, of mass graves, of corpses stacked at roadsides, and of bewildered groups of suddenly-orphaned children (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Orphans of the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic, Dillingham, AK

Source. Photographed in 1919 by Sue Brown French (1896–1980), whose husband Dr. Linus Hiram French (1876–1946) was caring for the orphans. Used by permission of their grandson, Charles Linus Black.

On this 100th anniversary of the 1918 pandemic, we should not only pause to remember and reflect but also to seek lessons that can help us prevent, control, and limit future tragic pandemics.

BACKGROUND

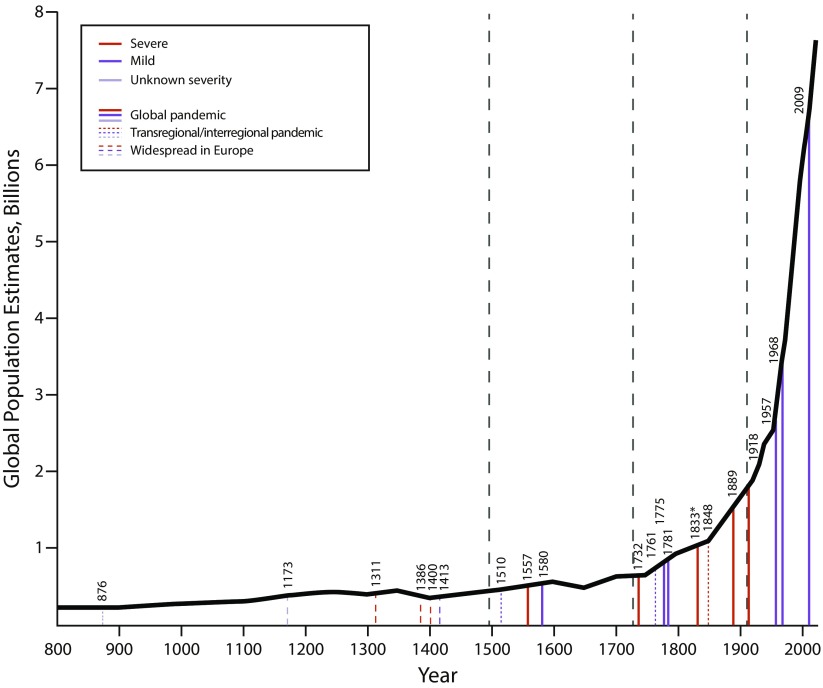

Influenza pandemics have recurred at irregular intervals since at least the ninth century AD (Figure 3).2 Signs and symptoms (fever, muscle aches, respiratory complaints) have remained unchanged over centuries. Deaths from influenza-associated pneumonias, with high mortality among very young and very old persons and pregnant women, have repeatedly been documented. The first identified influenza virus, a direct descendant of the 1918 pandemic virus, was isolated from a pig in 1931;3 the human 1918 virus was itself sequenced between 1995 and 2005 from pathology specimens and from a frozen corpse.4 Virus reconstruction and experimental study has led to important findings about its origin, evolution, and pathogenicity.5 The 1918 virus was a novel “founder virus” that has, over the past century, served as the mother of the descendant influenza A viral progeny that have been infecting and killing humans ever since.6,7

FIGURE 3—

Severe and Mild Pandemics of Presumed Influenza Between 876 and 2018, as a Function of Global Population and Geographic Extent

Note. In the era before clipper ships and rapid intercontinental travel (i.e., before the mid-19th century), widespread pandemics were sometimes hemispheric rather than global.2 Although human crowding and travel are associated with influenza spread and explosivity, the data do not suggest a clear role of human population size in the emergence of pandemics.

FROM WHERE DID THE 1918 VIRUS COME?

Despite popular hypotheses of pandemic origin in places such as central Spain; Étaples, France; the French countryside; or Camp Funston, Kansas, the 1918 pandemic—as identified by its extreme mortality—appeared globally almost everywhere at once (in July‒September 1918). Presumably, sometime before its recognition, the virus had already been silently seeded around the world, obscuring its place of origin. Such early transmission, beginning in or before 1918, reached pandemicity on exceeding critical detection thresholds in multiple large urban populations around the globe. Genetic sequences of viruses obtained from persons dying between May 1918 and February 1919, from victims as far apart as northwestern Alaska and London, show little variation and no evidence of evolution toward enhanced pathogenicity.

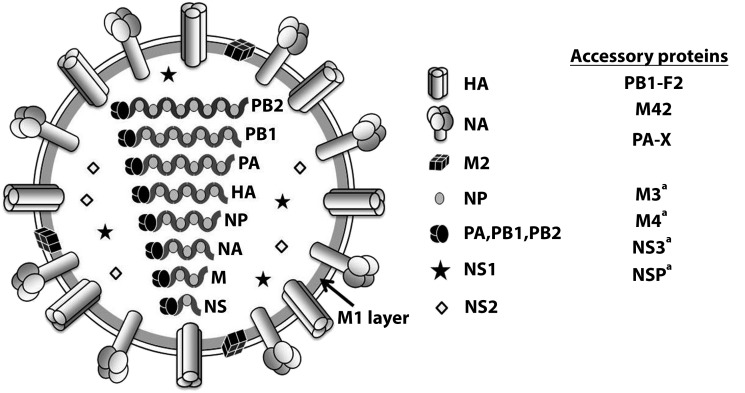

The reservoir of all influenza A viruses (Figure 4)8 is the global pool of billions of wild waterfowl and shore birds, within which they and their segmented genes continually circulate and reassort. Genetic, phylogenetic, and functional analyses of 1918 pandemic viral gene segments indicate a wild waterfowl influenza-like genome, reflecting an avian pandemic viral ancestor at some time in or shortly before 1918.9,10 It is worth noting that, apparently because of mutational penalties that limit further adaptations, gallinaceous poultry-adapted influenza viruses (such as modern day H5N1 and H7N9) may be limited in their ability to adapt to mammals or even to “back-adapt” to wild birds,11,12 making them unlikely pandemic viral ancestors. Poultry, in other words, are like mammals in being unnatural hosts for influenza viruses; viruses that adapt to transmission in these poultry hosts do so by undergoing complex mutational changes that appear to restrict further host-switching adaptations. However, certain wild waterfowl viruses have in recent years jumped directly into pigs or dogs,13,14 and equine-adapted influenza viruses have switched hosts to become dog-adapted viruses.15 Thus, along with the well-appreciated mechanisms of pandemic emergence noted above (Figure 4), two additional host-switching pathways for influenza A virus have been identified, suggesting that humans may also be at risk for future pandemics by means of similar emergence mechanisms.

FIGURE 4—

Diagram of an Influenza Virus With Its Eight Gene Segments and 11 or More Proteins

Note. Pandemics have resulted from (1) direct or intermediate emergences of wild waterfowl viruses, as occurred in the 1918 pandemic (the current pandemic era’s founder virus); (2) from acquisition of gene segments via reassortment of novel hemagglutinin (HA) subtypes with or without reassortment-associated acquisition of other novel genes (so-called antigenic shift); or (3) from complex evolutionary mechanisms such as occurred in the 2009 pandemic. Major HA changes arising in seasonal endemic viruses from intrasubtypic reassortment may also cause pandemics, as happened in 1946, although they are not usually referred to as such.7 Since 1918, pandemics caused by 1918-descended viruses7 have occurred in 1957 (referred to as H2N2 viruses after the subtypes of the HA and the neuraminidase [NA] proteins), 1968 (H3N2), and 2009 (H1N1, like its parent 1918 virus). Between pandemics, annual seasonal influenza A viruses are generated by continuous viral genetic mutations (antigenic drift) and by intrasubtypic reassortments.7

aPutative.

Source. This figure is modified from Taubenberger and Kash.8

WHY WAS THE 1918 PANDEMIC SO SEVERE?

Over centuries, influenza pandemics have been variably mild (e.g., in 1510 and in the modern era in 2009) or severe (e.g., in 1557 and in 1918; Figure 3).2 Pandemic influenza viruses almost certainly differ in inherent pathogenic properties. The 1918 H1N1 virus, for example, possesses a wild waterfowl-like H1 hemagglutinin associated with pathogenic potential as well as altered pathology in infections of mammals, including enhanced respiratory epithelial cytopathicity and elicitation of a strong proinflammatory host immune response.16 An epidemiological expression of inherent 1918 viral pathogenicity can be seen by comparing age-specific mortality rates in the age group that has experienced the lowest mortality in all pandemic and seasonal influenza occurrences observed to date: children aged 5 to 14 years. The 1918 mortality rate in this age range was variably four to five times that in the 1889 pandemic, presumably reflecting higher inherent viral pathogenicity (or viral–bacterial copathogenicity; see discussion in this section).

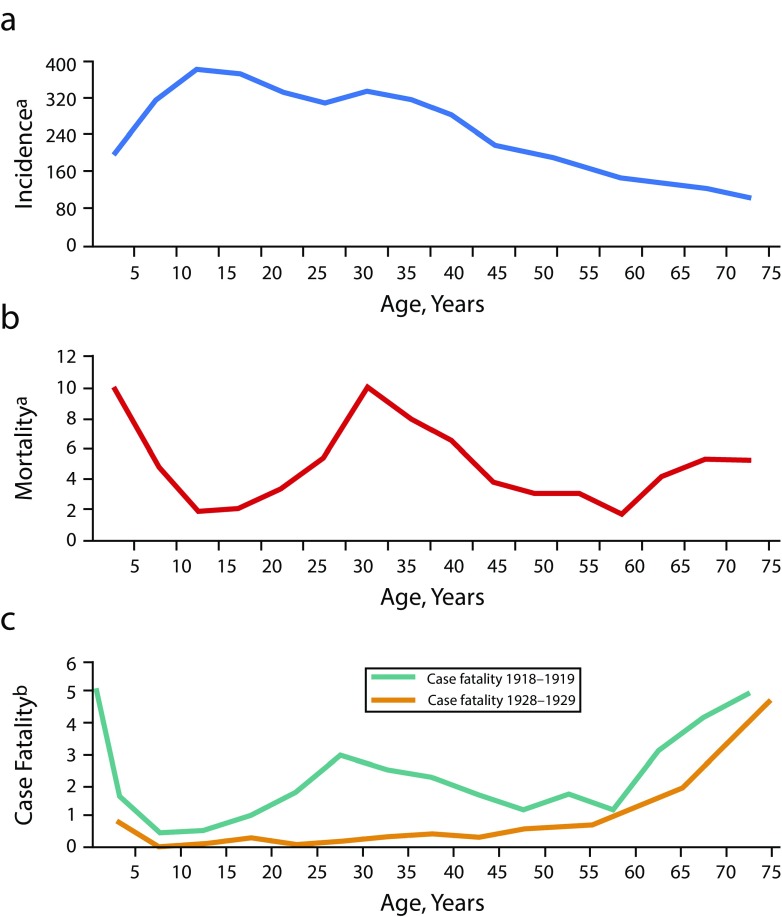

Another determinant of 1918 pandemic severity was the unprecedented age-specific mortality (and case fatality) pattern, in which young infected adults were at extraordinarily high risk of dying, a feature not seen before or since. Normally, influenza age-specific mortality (and case fatality) is U-shaped (Figure 5), with high mortality among very young and very old persons and low mortality among persons of all ages in between (excepting elevated mortality in pregnant women and in persons of any age with severe chronic conditions such as respiratory and cardiac diseases). The 1918 mortality curve, however, was W-shaped, with an additional mortality peak at least three times higher than expected among those aged 20 to 40 years, associated with a paradoxical drop in expected mortality among elderly persons (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5—

Age-Specific 1918–1919 Pandemic Influenza (a) Incidence, (b) Mortality, and (c) Case Fatality: United States

Note. P&I = pneumonia and influenza. The bottom figure also compares typical U-shaped age-specific case fatality in 1928–1929 (bottom figure, amber line) with the unique 1918–1919 W-shaped curve of case fatality. A U-shaped curve of age-specific mortality is not shown but is similar in all respects to age-specific case-fatality curves.

aPer 1000 persons per age group.

bPer 100 persons ill with pneumonia and influenza per age group.

Curiously, the highest mortality rate in the 20- to 40-year age range was among persons aged around 29 years in 1918 (i.e., those born in the year of the [then most recent] 1889 pandemic).17 This suggests that the W-shaped mortality curve could somehow be related to immunologic effects of previous influenza virus circulation. For example, lower-than-expected mortality among elderly persons in 1918 might reflect long-term exposures of that age cohort to a partially 1918-protective 1830s pandemic virus and to its pre-1889 descendants, with fewer chances for protective exposures to that virus lineage in persons born at the end of the 1830s viral era, just before 1889 (Figure 5). However, the declining 1918 mortality incidence in successive birth cohorts between 1889 and about 1904 could reflect a different mechanism of accumulating cohort protection associated with exposures to the new 1889 virus, or the 1830s virus may have continued to cocirculate for a period after 1889. These are, however, only speculative attempts to reconcile confusing epidemiologic observations. No theory about the underlying cause of the strange age-specific mortality pattern in 1918 has been generally accepted.

Such questions may nonetheless be important. Although partial 1918 mortality protection of elderly persons (in this case, protection from incident influenza despite the expected higher case fatality) was not definitively observed in 1889, it has been observed in every pandemic since, most recently in the 2009 swine influenza pandemic, in which a cause was first clearly characterized. In 2009, persons who had lived through the first decades of the 1918 pandemic H1N1 era, especially those born before about 1950, were substantially protected from the 2009 pandemic virus by having acquired immunity to the antigenically similar H1 or N1 of the 1918 virus, or both, or to the descendant seasonal H1N1 viruses that circulated over subsequent decades. This is because the 2009 H1 gene was a 1918 viral progeny that had survived for more than 90 years, with minimal antigenic drift, in a domestic pig “time capsule.”18

With respect to pathogenicity, it is of great importance that in experimental studies of 1918 modern waterfowl chimeric viruses,9 contemporary waterfowl H1 gene segments confer the same degree of extreme pathogenicity as the 1918 pandemic H1. Thus, if population immunity to H1 ever drops significantly, an H1 pandemic as deadly as that of 1918 might well result, suggesting also that indefinite maintenance of population H1 immunity may be an important component of pandemic prevention. Inherent avian H1 pathogenicity also argues against another popular myth, that the 1918 virus acquired pathogenicity by evolving in humans before the pandemic (e.g., in initially milder “herald waves”). Yet another myth is that 1918 severity was somehow related to the disruptions of World War I. Although determinants of influenza spread obviously include crowding and human movement, such as occurred during the war, it is worth noting that the 1918 pandemic spread over the whole globe, to combatant and noncombatant regions alike, at about the same pace. Indeed, it began in, and then raced through, noncombatant India before it began in most of war-torn Europe (although some Indian troops did fight in Europe). In addition, the highest 1918 influenza military mortality was in general not documented among troops on or near the front lines, but among US troops who were stateside in crowded training camp environments or in overcrowded transport ships.

As is almost always the case with communicable diseases, poor, disadvantaged, and malnourished persons and those who lived in crowded conditions were at higher risk of death in 1918. It is here worth noting that estimates of 1918–1919 global mortality have long been limited by absent or unreliable data from much of the developing world. Recent studies using newer demographic approaches,19,20 however, suggest that influenza mortality in some developing nations may have been even higher than previously thought, potentially arguing for an upward revision of the accepted estimate of 50 to 100 million pandemic deaths. This, too, has obvious implications for future efforts to protect populations with few resources.

Finally, an extremely important lesson is that virtually all 1918 influenza deaths were due not to influenza itself but to complicating secondary bacterial bronchopneumonias (including pneumonia-associated empyema and sepsis) caused by pneumopathogenic bacteria normally carried silently in the nasopharynx. The bacteria we now call Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus predominated.21 Moreover, the significant 1918 mortality peak in young adults was attributable not to more severe complicating pneumonias but to a higher case incidence of complicating pneumonias of typical case fatality in influenza-infected persons in this age group, compared with other age groups.22 Although the reasons for this difference in pneumonia case incidence are unknown, 1918 pandemic mortality would have been significantly lessened had it not been for secondary pneumonias.

FUTURE PREVENTION, CONTAINMENT, AND TREATMENT

We do not currently have tools to prevent the emergence of influenza pandemics. The viruses of future pandemics swirl around us as continually reassorting and evolving gene segments within the ever-moving pool of billions of wild waterfowl and other animal hosts. Better surveillance can improve understanding of avian viral circulation and evolution, but it is not likely to identify prepandemic viruses. It still takes months to develop and produce novel vaccines against novel pandemic influenza viruses; during such a prolonged interval, many deaths will inevitably occur.

We do, though, have a much better understanding of the utility of standard public health approaches, including those available in 1918, in limiting and slowing pandemics, as was seen in the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus. In 1918, families, schools, and remote locales often successfully isolated themselves to prevent infection; a US Navy blockade completely prevented the introduction of influenza into the islands of American Samoa. Other isolated locales escaped the pandemic entirely, some remaining free of any influenza for decades. Although public health efforts may not stop a future pandemic, they can potentially blunt it, reducing spread and mortality in the months it takes to manufacture and distribute vaccines. We can also identify persons at highest risk of severe influenza and prevent their exposure, infection, and disease through home self-confinement, home monitoring, and preventive administration of antivirals. Instituting community prevention with public education, hand sanitation, N95 masks, work leave policies, school closures, and other actions could also blunt future pandemics.

It was universally agreed in 1918 that the single variable most associated with influenza survival was good nursing care, including care provided in the home. Nurses, some professionals, others untrained volunteers or family members or friends, were among the great heroes and heroines of the pandemic (Figure 6). It is worth asking how they saved so many lives without effective specific treatments. Although scientific data are not available to answer this question, those who pondered it in 1918 cited nutrition, rest, warmth, fluids, fresh air, the comforting presence of another, and in many instances the maintenance of protective isolation of ill persons. US military camps demonstrated that high influenza mortality resulted in great part from “colonization epidemics” of pneumopathogenic bacteria associated with men living in close quarters23; when incident influenza infection damaged respiratory epithelium, silently colonizing nasopharyngeal bacteria with pneumopathogenic potential were able to spread into the lungs to cause fatal pneumonias. Early patient isolation and effective nursing of ill persons may have lowered mortality in 1918 by preventing other persons from transmitting pneumopathogenic bacteria to them, as was documented in military camps.

FIGURE 6—

American Red Cross Nurses During the 1918–1919 Pandemic

Note. Trained and volunteer nurses, an important part of the medical and public health response during the pandemic, are credited with saving many lives. Female scientists also stepped into temporary leadership roles when their (male) supervisors entered the military during World War I. Many such progressive women—for example, Rush Medical College’s Ruth Tunnicliff (1876–1946), who worked at the Camp Pike, Little Rock, AR, military training camp, during the 1918 pandemic, and the Rockefeller Institute’s Martha Wollstein (1868–1939)—made important scientific contributions related to influenza.23 These important advances occurred at the height of the suffragist movement; American women were given state voting rights beginning in 1910 and national voting rights in 1920.

Source. Photograph used by permission of the American Red Cross.

Ironically, the many 1918 autopsies that established secondary bacterial pneumonias as the principal causes of death21 also demonstrated rapid repair of viral damage, suggesting that today early antibiotic and intensive care treatment of postinfluenza bacterial bronchopneumonia should lead to recovery. We now have effective treatments not only for the three predominant bacteria of 1918 but for many other pathogenic bacteria as well. A still unresolved critical problem, however, is that progression from typical influenza to explosive bronchopneumonia may be so rapid that only very early detection and treatment can be life saving. In a modern pandemic of 1918 severity, as many as two or more million Americans could die in the span of a few weeks without early diagnosis of impending bronchopneumonia, immediate hospitalization, and critical care, including intravenous antibiotics and mechanical ventilation. Of great research importance is the need to identify early biomarkers for impending bacterial pneumonia in influenza patients, who are likely to be chest X-ray negative upon presentation.

Finally, we now have moderately effective influenza vaccines and a standing production capacity based on a reliable viral platform that can be scaled up to deliver vaccine across the nation within about six months. We also have pneumococcal vaccines and public health recommendations for the use of both types of vaccines. Developing vaccines against other bacteria likely to cause secondary bacterial pneumonias in a future influenza pandemic, especially S. aureus, should be a high priority. Revitalized attempts to develop influenza vaccines that afford broader and more durable protection (so-called universal influenza vaccines)24 are likely to result in better, if less-than-universal, vaccines in coming years. Study of past pandemics may help us design better vaccines: For example, blunting of pandemic mortality in elderly persons in both 1918 and 2009 suggests the importance of cumulative exposures to related viruses in designing prepandemic vaccines.

LOOKING AHEAD TO THE COMING CENTURY

We have learned more about influenza from the 1918 pandemic and its aftermath than from influenza occurrences in all previous centuries combined. Although future pandemics may not be preventable, we have substantial knowledge about pandemic risk management, including standard public health measures to protect individuals, and more effective cooperation between medicine and public health. We also have reason to think that we can successfully implement community prevention measures, slowing pandemic viral spread to buy time for vaccine manufacture and seasonal decreases in transmission. We may even be able someday to develop vaccines that can prevent pandemics of any hemagglutinin or neuraminidase subtype. However, much more vaccine research is needed, including a better understanding of the basis of, and correlates of, natural and vaccine-induced immunity, focusing especially on the mucosal immune system. This will require the application of modern research tools to more fully characterize influenza’s natural history and pathogenesis in live virus challenge studies of both humans and experimental animals.

A century after the world’s deadliest pandemic, we are still energetically studying it, and we appear to stand at the threshold of discoveries that will one day save millions of lives if, or rather when, another highly fatal influenza pandemic emerges.

We are still searching, but we are certainly not lost.

Footnotes

See also Parmet and Rothstein, p. 1435.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolfe T. Look Homeward, Angel: A Story of the Buried Life. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons; 1929. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. Pandemic influenza: certain uncertainties. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:262–284. doi: 10.1002/rmv.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shope RE. The etiology of swine influenza. Science. 1931;73(1886):214–215. doi: 10.1126/science.73.1886.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taubenberger JK, Hultin JV, Morens DM. Discovery and characterization of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus in historical context. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:581–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kash JC, Taubenberger JK. The role of viral, host, and secondary bacterial factors in influenza pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(6):1528–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 1918 influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(1):15–22. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. The persistent legacy of the 1918 influenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):225–229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taubenberger JK, Kash JC. Influenza virus evolution, host adaptation, and pandemic formation. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(6):440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qi L, Davis AS, Jagger BW et al. Analysis by single-gene reassortment demonstrates that the 1918 influenza virus is functionally compatible with a low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus in mice. J Virol. 2012;86(17):9211–9220. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00887-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabadan R, Levine AJ, Robins H. Comparison of avian and human influenza A viruses reveals a mutational bias on the viral genomes. J Virol. 2006;80(23):11887–11891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01414-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. H7N9 avian influenza A virus and the perpetual challenge of potential human pandemicity. MBio. 2013;4(4):e00445–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00445-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. Pandemic influenza—including a risk assessment of H5N1. Rev Sci Tech. 2009;28(1):187–202. doi: 10.20506/rst.28.1.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunham EJ, Dugan VG, Kaser EK et al. Different evolutionary trajectories of European avian-like and classical swine H1N1 influenza A viruses. J Virol. 2009;83(11):5485–5494. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02565-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parrish CR, Murcia PR, Holmes EC. Influenza virus reservoirs and intermediate hosts: dogs, horses, and new possibilities for influenza virus exposure of humans. J Virol. 2015;89(6):2990–2994. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03146-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. Historical thoughts on influenza viral ecosystems, or behold a pale horse, dead dogs, failing fowl, and sick swine. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2010;4(6):327–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi L, Pujanauski LM, Davis AS et al. Contemporary avian influenza A virus subtype H1, H6, H7, H10, and H15 hemagglutinin genes encode a mammalian virulence factor similar to the 1918 pandemic virus H1 hemagglutinin. MBio. 2014;5(6):e02116–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02116-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viboud C, Eisenstein J, Reid AH, Janczewski TA, Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. Age- and sex-specific mortality associated with the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in Kentucky. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(5):721–729. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kash JC, Qi L, Dugan VG et al. Prior infection with classical swine H1N1 influenza viruses is associated with protective immunity to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2010;4(3):121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandra S, Kassens-Noor E. The evolution of pandemic influenza: evidence from India, 1918-19. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):510. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra S. Mortality from the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 in Indonesia. Popul Stud (Camb) 2013;67(2):185–193. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.754486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(7):962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britten RH. The incidence of epidemic influenza, 1918-19. A further analysis according to age, sex, and color of the records of morbidity and mortality obtained in surveys of 12 localities. Public Health Rep. 1932;47(6):303–339. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. A forgotten epidemic that changed medicine: measles in the US Army, 1917-18. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(7):852–861. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JK, Taubenberger JK. Universal influenza vaccines: to dream the possible dream? ACS Infect Dis. 2016;2(1):5–7. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]