Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The golden Syrian hamster is an emerging model organism. To optimize its use, our group has made the first genetically engineered hamsters. One of the first genes that we investigated is KCNQ1 which encodes for the KCNQ1 potassium channel and also has been implicated as a tumor suppressor gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We generated KCNQ1 knockout (KO) hamsters by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene targeting and investigated the effects of KCNQ1-deficiency on tumorigenesis.

RESULTS:

By 70 days of age seven of the eight homozygous KCNQ1 KOs used in this study began showing signs of distress, and on necropsy six of the seven ill hamsters had visible cancers, including T-cell lymphomas, plasma cell tumors, hemangiosarcomas, and suspect myeloid leukemias.

CONCLUSIONS:

None of the hamsters in our colony that were wild-type or heterozygous for KCNQ1 mutations developed cancers indicating that the cancer phenotype is linked to KCNQ1-deficiency. This study is also the first evidence linking KCNQ1-deficiency to blood cancers.

Keywords: Golden Syrian hamster, KCNQ1, tumor suppressor

Introduction

The golden Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) is an emerging model organism for human diseases that complements current rodent models. It has been demonstrated to be especially effective in modeling human disorders such as inflammatory myopathies, emerging viral infectious diseases, Clostridium difficile infection, pancreatitis, diet-induced obesity, and early atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and virally and chemically induced cancers.[1,2] However, until recently, a significant challenge for the use of hamsters in modeling human diseases was the inability to generate genetically engineered hamsters. This barrier has recently been surmounted, resulting in gene knockouts (KOs) and knockins in the hamster by employing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene targeting, PiggyBac-mediated transgenesis, and pronuclear injection.[3,4] This permitted the creation of the first genetic models of cancer in hamsters. One of the first genes that we investigated encodes for the KCNQ1 potassium channel. KCNQ1 is widely expressed in human and rodent tissues, including heart, skeletal muscle, smooth muscle, inner ear, renal proximal tubules, gastric parietal cells, exocrine pancreas, intestinal epithelia, lung, hepatocytes, breast, bone marrow, thymic T cells, and white blood cells.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] KCNQ1 protein expression data in humans from the human protein atlas[15] indicates that KCNQ1 expression is considered high in thyroid, parathyroid and adrenal glands, in stomach and duodenum, and seminal vesicles; medium in heart, cerebellum, bone marrow, skeletal and smooth muscle, lung, liver, pancreas, oral mucosa, jejunum and ileum, colorectum, kidney, breast, skin, placenta, and uterus; and low in cerebral cortex, hippocampus, salivary glands, esophagus, testis and ovary (www.proteinatlas.org). KCNQ1 can act as either an S4 domain-containing voltage-gated potassium ion channel or as a constitutively active channel, depending on the identity of its KCNE subfamily heterodimeric partner.[12,16] KCNQ1 function is best known for its voltage-gated interaction with its KCNE1 heterodimeric partner, such as in cardiac myocyte repolarization.[12] In contrast, when KCNQ1 partners with KCNE3, as in the intestinal epithelium, KCNE3 locks open the KCNQ1 S4 domain to remove the voltage dependence of KCNQ1 activation, converting it to a constitutively active K+ channel.[12] The KCNQ1 gene is developmentally imprinted, with its expression controlled by a long noncoding RNA, KCNQ1ot1, that lies within exon 10 of the KCNQ1 gene (and which is itself reciprocally imprinted).[17] A large number of novel enhancers at the KCNQ1 locus are reported to regulate the expression of KCNQ1 in specific tissues[18] and Wnt/β-catenin signaling is implicated in the regulation of both KCNQ1 and KCNQ1ot1.[19,20,21] KCNQ1 mutations cause a range of disease in humans such as cardiac arrhythmia (Long QT syndrome), inner ear defects, and gastric hyperplasia.[22,23] Germline mutations in humans are associated with disorders called Romano-Ward Syndrome and Jervell and Lange-Nielson Syndrome.[23] Notably, KCNQ1 has been shown to act as a tumor suppressor in mouse and human gastrointestinal cancers.[24,25,26] In our current study, eight KCNQ1 homozygous KO hamsters were aged and phenotyped. As early as 70 days of age, seven of these homozygous mutants started showing signs of distress, and on necropsy six of the seven ill hamsters had aggressive visible cancers.

Materials and Methods

Creation of KCNQ1 knockout hamsters

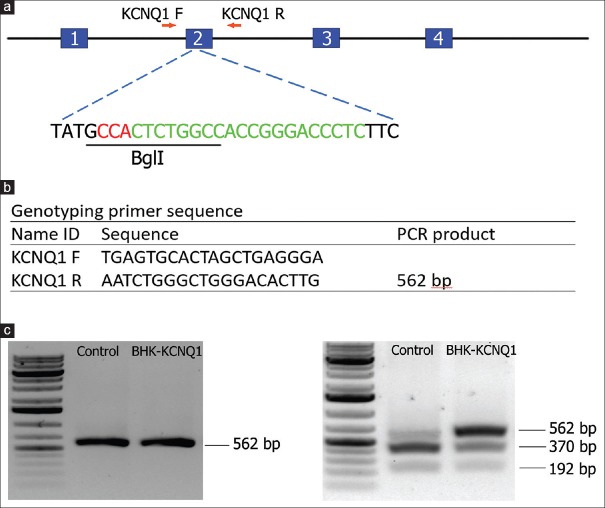

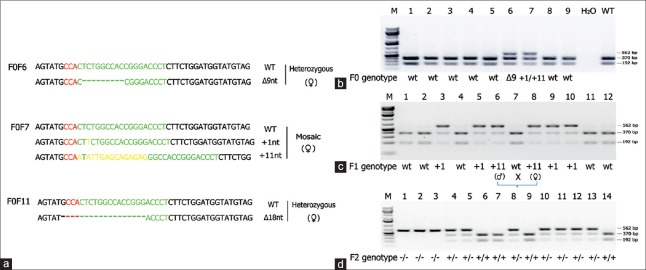

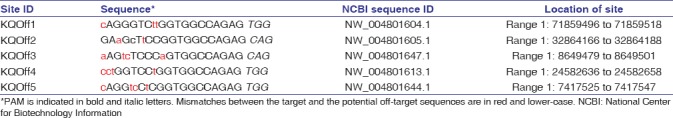

The KCNQ1 gene was knocked out in hamsters by CRISPR/Cas9 gene targeting and pronuclear injection following a protocol previously described.[3,4] Briefly, a sgRNA/Cas9 gene targeting vector designed for hamster KCNQ1 was constructed using the pX330-U6-Chimeric BB-CBh-hSpCas9 plasmid (Addgene ID: 42230).[27] The final construct was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The design of the KCNQ1 KO allele is depicted in Figure 1a. The 11 bp insertion abolishes a BglI restriction enzyme site, thereby genotyping was carried out by a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) assay. PCR primers are listed in Figure 1b. To determine the success of the design, genotyping and targeting efficiency, gene targeting was conducted in baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells. BHK fibroblasts (BHK; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, nonessential amino acids, and Penicillin-Streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A volume of 5 mg of circular sgRNA/Cas9 vectors were transfected into 106 BHK cells using Amaxa 4D-Nucleofector (Program No. CA-137; Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA). Two days posttransfection, cells were harvested for genomic DNA isolation using Puregene Core Kit A (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Target DNA was PCR amplified from the genomic DNA isolated from BHK cells using Phusion High-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), [Figure 1c] (left). After digestion with BglI, the PCR products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel and stained with SYBR green dye (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) [Figure 1c] (right). To determine gene targeting efficiency, the relative intensities of uncut band and cut bands were analyzed using the Image J software (1.47p, NIH). To produce KCNQ1 KO hamsters, we microinjected the sgRNA/Cas9 gene targeting vector into the pronuclei of hamster zygotes, followed by transferring the injected hamster embryos to recipient females and allowed the resultant pregnant females to naturally deliver and raise the pups. Genotyping analysis of the F0 pups was done by PCR-RFLP assays, and the genotyping results for F0 pups are shown in Figure 2a. To reveal the nature of the indels introduced, genomic PCR products used in the PCR-RFLP assays for each of the pups were subcloned into TA cloning vectors and sequenced by Sanger sequencing. To establish a KCNQ1 KO breeding colony, we bred F0F7 (female; carrying both + 1nt and + 11nt indels) with a WT male. Genotyping analysis with the PCR-RFLP assays showed that both the +1nt and + 11nt indels transmitted to the germline [Figure 2b]. Genotyping results by the PCR-RFLP assay on F2 pups produced sister–brother breeding between two heterozygous F1 pups (#6 and #8) [Figure 2c], both carrying the + 11nt allele, and produced three homozygous KO (#1, 2, and 3), 7 heterozygous KO (#4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 12, and 13) and four WT (#6, 7, 9, and 14) F2 pups [Figure 2d]. To identify potential off-targets, we did blast searches with the sgRNA coding sequence as the query against the hamster genome (https://uswest.ensembl.org/Mesocricetus_auratus/Info/Index). Top potential off-targets for sgRNAs are listed in Table 1. The corresponding DNA oligos for each of the targeting sites were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa, USA). We performed PCR-RFLP assays for each of these genomic loci but did not identify any off-targeting events. KCNQ1 homozygous KO hamsters demonstrate similar neurological defects (unpublished data from our group) as KO mice,[25] including deafness, inner ear defects, head bobbing, and smaller stature. For this reason, breeding required crosses between heterozygous animals. Hamster histopathology on formalin-fixed tissues was conducted by two trained pathologists at our institutions pathology core facility. All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at our universities.

Figure 1.

KCNQ1 gene targeting in golden Syrian hamsters by CRISPR/Cas9. (a) Schematic diagram for the hamster KCNQ1 genomic locus and the site targeted by the sgRNA. Letters in red are the PAM sequence, letters in green are the sgRNA targeting sequence, and the restriction enzyme recognition site (BglI) used for the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay is underlined. (b) Primer sequences for genotyping. (c) Gel images from the baby hamster kidney cell transfection assay results indicating the success of the design and genotyping and efficiency before pronuclear injection. Left, uncut with BglI; right, cut with BglI

Figure 2.

Establishment of a breeding colony of KCNQ1 knockout hamsters. (a) Indels introduced into KCNQ1 in 3 F0 founder hamsters. wild-type; Δnt and + nt: nucleotide deletions and insertions, respectively. The +11nt allele in F0F7 is the result from the replacement of a CT dinucleotides by 13 random nucleotides. (b) Genotyping result of the PCR-RFLP assay on a litter of F0 founder hamsters. F0F6 carries a Δ 9nt indel and F0F7 carries both +1nt and +11nt indels. (c) Genotyping results with the PCR-RFLP assay on F1 pups produced from breeding an F0F7 (female) with a WT male. Indels in each of the targeted pups were revealed by Sanger sequencing. (d) Genotyping results by the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay on F2 pups produced from sister-brother breeding between two heterozygous F1 pups (#6 and #8) both carry a +11nt allele from the F0F7 founder as indicated in C)

Table 1.

Top 5 potential off-target sites for sgRNA/Cas9-KCNQ1

Results

Cancers in KCNQ1 knockout hamsters

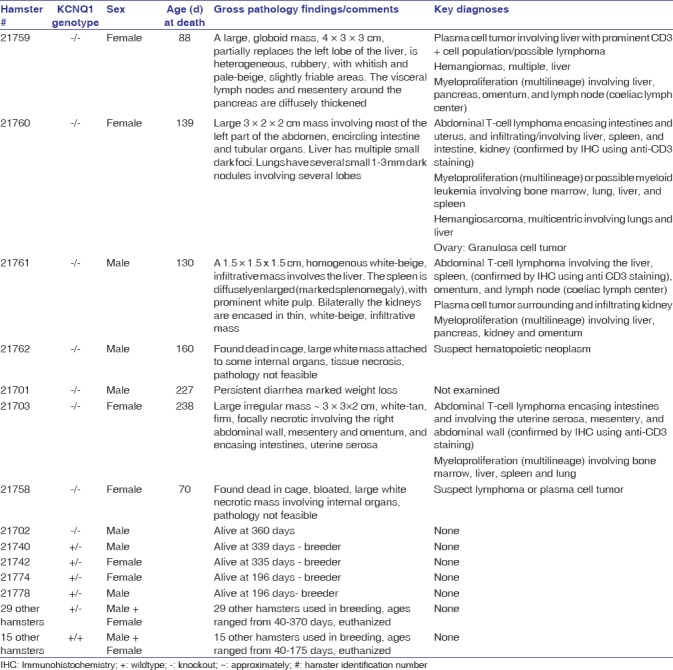

Seven of the eight homozygous mutants developed severe physical distress beginning at ~70 days of age, including six hamsters with overt cancers at necropsy. The cancers were synchronous, often large and infiltrative to multiple organs – liver, lung, pancreas and omentum, intestine, kidney, spleen, sternum, lymph nodes, and stomach in addition to systemic myeloproliferative disease involving bone marrow, lung, liver, and spleen. The major cancers observed were T-cell lymphomas, plasma cell tumors, and hemangiosarcomas (HAS). None of the 48 hamsters in our colony that were wild-type or heterozygous KO for KCNQ1 developed cancers indicating that the cancer phenotype is linked to KCNQ1-deficiency. Heterozygous animals were also generally phenotypically normal. As shown in Table 2, a detailed description of all hamsters including gross and microscopic pathology findings and diagnoses.

Table 2.

List of all hamsters

T-cell lymphomas

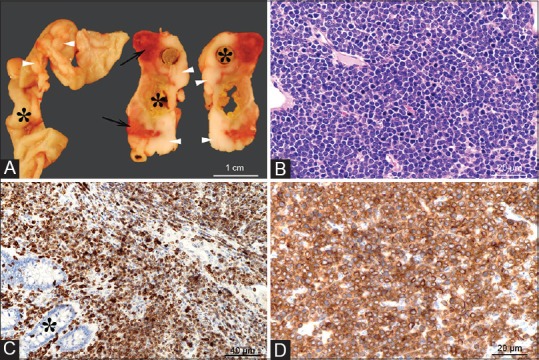

T-cell lymphomas were the most common cancers observed in hamsters. Three hamsters were diagnosed with abdominal masses and T-cell lymphoma involving liver, spleen, kidney, small intestine, colon, pancreas and omentum, based on histopathology and anti-CD3 immunohistochemistry [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Gross and microscopic images of an intestinal T-cell lymphoma. Grossly (Panel A), extending from the intestinal wall through the serosa and mesentery, there are multifocal to coalescing white-beige masses (arrowheads), with focal areas of necrosis and hemorrhage (arrows). The tumors circumferentially surround the intestines (indicated by asterisks) which are occasionally moderately dilated and segmentally ulcerated (transmural). Histologically, the tumor consists of densely packed sheets of round to oval cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm (Panel A) that infiltrate the intestinal mucosa (Panel C, asterisk) and subjacent layers through to intestinal serosa. The cells show a uniform, intense immunolabeling of plasma membrane for CD3 (Panels C and D) (anti-CD3 antibody, DAKO/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA; Cat# A0452). H and E, ×40 objective Panel B; CD3 immunolabeling with ×20 objective Panel C, and with ×40 objective Panel D

Plasma cell tumors

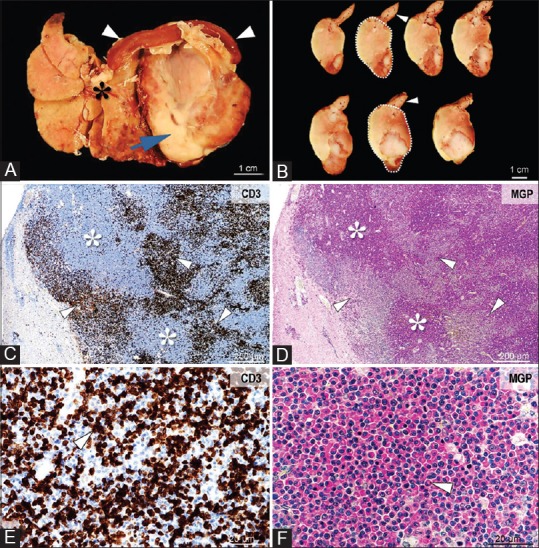

Plasma cell neoplasms, similar to multiple myeloma in humans, were diagnosed in two hamsters by histopathology and methyl green-pyronin staining, and found in liver, pancreas, spleen, omentum, lymph nodes, and mesentery. In one hamster, a plasma cell tumor mass measuring 4 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm engulfed the liver, pancreas, spleen, and associated lymph nodes and local mesentery. A prominent lymphoid population (suspect lymphoma) was found co-infiltrating the plasma cell tumor in these animals. Plasma cells were also found co-infiltrating tissues with T-cell lymphoma [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Gross and microscopic images of lymphoma and a plasma cell tumor involving the liver. Grossly, the tumor (Panel A, arrow) infiltrates and displaces the liver (Panel A, asterisk) and spleen (Panel A, arrowhead). On cross-section, the tumor (Panel B, demarked area) is heterogeneous, white-beige, friable, with large areas of necrosis and hemorrhage (Panel B, arrowheads). Histologically, the tumor consists of large areas of neoplastic plasma cells (Panel C and D, asterisks), associated with coalescing foci of CD3 immunopositive lymphocytes (Panel C-E, arrowheads). The densely packed plasmacytoid cells are round to oval, with variably sized, and eccentrically placed nuclei with coarse chromatin, a prominent Golgi area, and cytoplasm that stain intensely for methyl green-pyronin (Panel F, arrowhead). CD3 immunolabeling, objective ×4 (Panel C) and × 40 (Panel E). Methyl green-pyronin stain for plasma cells, objective ×4 (Panel D) and ×40 (Panel F)

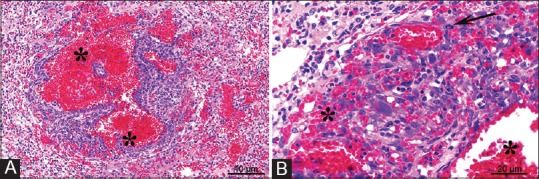

Hemangiosarcoma

HSA, while a common cancer in canines,[28] is rare in humans and rodents. Based on pathology, we observed multifocal HSA in the lungs and HSA and hemangiomas in the liver of two hamsters [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Histopathological images of a locally infiltrative multicentric hemangiosarcoma involving lung. Tumor composed of pleomorphic, oval to spindle-shaped cells that form irregularly shaped, blood-field vascular spaces (asterisks Panels A and B), with occasional atypical mitotic figures (Panel B, arrow). H and E, ×20 objective Panel A, ×40 objective Panel B

Myeloid disease and other suspect cancers and findings

Myeloproliferative disease was observed in four animals (with possible myeloid leukemia in one animal) involving bone marrow, lung, liver, and spleen; this involved multiple lineages, notably, the granulocytic series (heterophil, sometimes eosinophil), and in addition plasma cells, megakaryocytes and red cells to varying degrees. In one hamster, a prominent myeloid/polymorphonuclear population was observed in the bone marrow that was also infiltrating the adjacent fibrous connective tissue of the sternum and striated muscle. One hamster was diagnosed with granulosa cell tumor involving the ovaries.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the creation of the first genetically engineered hamster cancer model. Our work is also the first evidence linking KCNQ1-deficiency to blood cancers. How might KCNQ1-deficiency cause blood cancers in hamsters? In humans and mice, KCNQ1 has been reported to be expressed in several types of hematopoietic cells, including thymic T cells,[14] bone marrow (www.proteinatlas.org), and murine white blood cells,[13] although KCNQ1 expression patterns in hamsters have not been fully characterized. There is also a report that disruption of KCNQ1 in mice results in an accumulation of mature T cells.[14] One mechanistic possibility is that KCNQ1 may synergize with hamster polyomavirus (HaPV). HaPV is thought to be endemic in hamster colonies worldwide (including ours), and an outbreak of lymphomas was reported in a colony in Spain of the genetic audiogenic seizure-prone hamster: Salamanca strain of hamsters susceptible to audiogenic seizures.[29] Notably, studies of this colony have suggested that the seizure phenotype may be linked to a deficiency for the nonvoltage-gated KCC2 potassium channel in the brain.[30] Thus, there is the possibility that a potassium channel deficiency may cooperate with HaPV in cancer development. More specifically, deficiency for the voltage-gated KCNQ1 potassium channel could cause membrane depolarization in bone marrow-derived stem cells, contributing to their transformation. A role for KCNQ1 in regulation of stem cell transformation has been proposed for KCNQ1-deficiency in gastrointestinal cancer, arising from bidirectional Wnt/β-catenin signaling.[21] Consistent with this, in GI cancer KCNQ1 expression was linked to the regulation of intestinal stem cell mRNA in mice,[25] and KCNQ1 protein expression has been localized to the intestinal stem cell compartment of intestinal crypts (unpublished work by our group). Further support for a role in stem cells is a report of KCNQ1 expression in a murine bone marrow-derived pluripotent small embryonic/epiblast-derived stem cell Very small embryonic-like stem cells.[31] Future studies will need to analyze whether Wnt/β-catenin signaling is dysregulated in KCNQ1-deficient bone marrow-derived hamster progenitor cells, especially with the emerging evidence of a major role for Wnt signaling in hematological malignancies.[32] Finally, the observation of HAS in addition to neoplasia involving several hematopoietic cell lineages in these hamsters is interesting, and appears to be consistent with the finding of this tumor in dogs and its attribution to transformation of a common progenitor hematopoietic cell.[28]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the University of Minnesota Medical School (to RTC); by Essentia Health Systems (to RTC); and grants from the Utah Science Technology and Research initiative and NIH (1R41OD021979-01) (to ZW).

References

- 1.Li Z, Xiong C, Mo S, Tian H, Yu M, Mao T, et al. Comprehensive transcriptome analyses of the fructose-fed Syrian golden hamster liver provides novel insights into lipid metabolism. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wold WS, Toth K. Chapter three – Syrian hamster as an animal model to study oncolytic adenoviruses and to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral compounds. Adv Cancer Res. 2012;115:69–92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398342-8.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan Z, Li W, Lee SR, Meng Q, Shi B, Bunch TD, et al. Efficient gene targeting in golden Syrian hamsters by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. PLoS One. 2014;9:e109755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li R, Miao J, Fan Z, Song S, Kong IK, Wang Y, et al. Production of genetically engineered golden Syrian hamsters by pronuclear injection of the CRISPR/Cas9 complex. J Vis Exp. 2018;131 doi: 10.3791/56263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, et al. Coassembly of K (V)LQT1 and MinK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–3. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finsterer J, Stöllberger C. Skeletal muscle involvement in congenital long QT syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2004;25:238–40. doi: 10.1007/s10072-004-0329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wangemann P. Supporting sensory transduction: Cochlear fluid homeostasis and the endocochlear potential. J Physiol. 2006;576:11–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallon V, Grahammer F, Volkl H, Sandu CD, Richter K, Rexhepaj R, et al. KCNQ1-dependent transport in renal and gastrointestinal epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17864–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505860102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heitzmann D, Grahammer F, von Hahn T, Schmitt-Gräff A, Romeo E, Nitschke R, et al. Heteromeric KCNE2/KCNQ1 potassium channels in the luminal membrane of gastric parietal cells. J Physiol. 2004;561:547–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolas M, Demêmes D, Martin A, Kupershmidt S, Barhanin J. KCNQ1/KCNE1 potassium channels in mammalian vestibular dark cells. Hear Res. 2001;153:132–45. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeder BC, Waldegger S, Fehr S, Bleich M, Warth R, Greger R, et al. Aconstitutively open potassium channel formed by KCNQ1 and KCNE3. Nature. 2000;403:196–9. doi: 10.1038/35003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott GW. KCNE1 and KCNE3: The yin and yang of voltage-gated K(+) channel regulation. Gene. 2016;576:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez-Úriz AM, Milagro FI, Mansego ML, Cordero P, Abete I, De Arce A, et al. Obesity and ischemic stroke modulate the methylation levels of KCNQ1 in white blood cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:1432–40. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chabannes D, Barhanin J, Escande D. Mice disrupted for the kvLQT1 potassium channel regulator IsK gene accumulate mature T cells. Cell Immunol. 2001;209:1–9. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thul PJ, Lindskog C. The human protein atlas: A spatial map of the human proteome. Protein Sci. 2018;27:233–44. doi: 10.1002/pro.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liin SI, Barro-Soria R, Larsson HP. The KCNQ1 channel-remarkable flexibility in gating allows for functional versatility. J Physiol. 2015;593:2605–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.287607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanduri C. Kcnq1ot1: A chromatin regulatory RNA. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultz BM, Gallicio GA, Cesaroni M, Lupey LN, Engel N. Enhancers compete with a long non-coding RNA for regulation of the kcnq1 domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:745–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunamura N, Ohira T, Kataoka M, Inaoka D, Tanabe H, Nakayama Y, et al. Regulation of functional KCNQ1OT1 lncRNA by β-catenin. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20690. doi: 10.1038/srep20690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilmes J, Haddad-Tóvolli R, Alesutan I, Munoz C, Sopjani M, Pelzl L, et al. Regulation of KCNQ1/KCNE1 by β-catenin. Mol Membr Biol. 2012;29:87–94. doi: 10.3109/09687688.2012.678017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rapetti-Mauss R, Bustos V, Thomas W, McBryan J, Harvey H, Lajczak N, et al. Bidirectional KCNQ1:β-catenin interaction drives colorectal cancer cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:4159–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702913114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedley PL, Jørgensen P, Schlamowitz S, Wangari R, Moolman-Smook J, Brink PA, et al. The genetic basis of long QT and short QT syndromes: A mutation update. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1486–511. doi: 10.1002/humu.21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano Y, Shimizu W. Genetics of long-QT syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2016;61:51–5. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starr TK, Allaei R, Silverstein KA, Staggs RA, Sarver AL, Bergemann TL, et al. Atransposon-based genetic screen in mice identifies genes altered in colorectal cancer. Science. 2009;323:1747–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1163040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Than BL, Goos JA, Sarver AL, O’Sullivan MG, Rod A, Starr TK, et al. The role of KCNQ1 in mouse and human gastrointestinal cancers. Oncogene. 2014;33:3861–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.den Uil SH, Coupé VM, Linnekamp JF, van den Broek E, Goos JA, Delis-van Diemen PM, et al. Loss of KCNQ1 expression in stage II and stage III colon cancer is a strong prognostic factor for disease recurrence. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1565–74. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorden BH, Kim JH, Sarver AL, Frantz AM, Breen M, Lindblad-Toh K, et al. Identification of three molecular and functional subtypes in canine hemangiosarcoma through gene expression profiling and progenitor cell characterization. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:985–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muñoz LJ, Ludeña D, Gedvilaite A, Zvirbliene A, Jandrig B, Voronkova T, et al. Lymphoma outbreak in a GASH: Sal hamster colony. Arch Virol. 2013;158:2255–65. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1737-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muñoz LJ, Carballosa-Gautam MM, Yanowsky K, García-Atarés N, López DE. The genetic audiogenic seizure hamster from Salamanca: The GASH: Sal. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;71:181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin DM, Liu R, Klich I, Ratajczak J, Kucia M, Ratajczak MZ, et al. Molecular characterization of isolated from murine adult tissues very small embryonic/epiblast like stem cells (VSELs) Mol Cells. 2010;29:533–8. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grainger S, Traver D, Willert K. Wnt signaling in hematological malignancies. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2018;153:321–41. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]