Abstract

Objective:

To illustrate the concept of work-life balance and those factors that influence it and to provide recommendations to facilitate work-life balance in athletic training practice settings. To present the athletic trainer with information regarding work-life balance, including those factors that negatively and positively affect it within the profession.

Background:

Concerns for work-life balance have been growing within the health care sector, especially in athletic training, as it is continuously linked to professional commitment, burnout, job satisfaction, and career longevity. The term work-life balance reflects those practices used to facilitate the successful fulfillment of the responsibilities associated with all roles one may assume, including those of a parent, spouse, partner, friend, and employee. A host of organizational and individual factors (eg, hours worked, travel demands, flexibility of work schedules, relationship status, family values) negatively influence the fulfillment of work-life balance for the athletic trainer, but practical strategies are available to help improve work-life balance, regardless of the practice setting.

Recommendations:

This position statement is charged with distributing information on work-life balance for athletic trainers working in a variety of employment settings. Recommendations include a blend of organizational and personal strategies designed to promote work-life balance. Establishing work-life balance requires organizations to have formal policies that are supported at the departmental and personal level, in addition to informal policies that reflect the organizational climate of the workplace. Individuals are also encouraged to consider their needs and responsibilities in order to determine which personal strategies will aid them in attaining work-life balance.

Key Words: quality of life, mentoring, burnout, job satisfaction, professional commitment, wellbeing

Health care professionals are recognized as interpersonal, caring, and compassionate individuals who provide patient-centered care.1 The giving nature of health care providers coupled with long working hours can leave individuals susceptible to burnout,2–11 a syndrome characterized by emotional and physical exhaustion and facilitated by prolonged stress, overload, and intermittent feelings of being undervalued and underappreciated.12 Athletic trainers (ATs) continue to establish their worth and value in health care, as demonstrated by the growth in employment settings; however, at times, attaining appropriate recognition and respect has been a struggle.13,14 In addition to feeling valued, being fairly compensated and having the opportunity to find and achieve an adequate work-life balance have become central objectives for ATs and the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA).15,16 These initiatives are supported by the relationships among work-life balance, job satisfaction, and retention of ATs in the profession.17,18

Work-life balance involves effectively managing one's paid occupation and those personal activities and responsibilities important to one's wellbeing in order to reduce conflicting experiences.19–21 Conceptually, work-life balance is viewed as a positive relationship in which an individual can be engaged in various roles (eg, parent, employee, spouse, caregiver, runner) and relatively satisfied with the time spent in each role. Fulfillment of work-life balance is largely based on the individual's interests and selection of roles. Work-life balance is often associated with quality of life and has been linked to a variety of outcomes, including burnout, job satisfaction, professional commitment, health and wellness, and career intentions. Over the last decade, work-life balance has garnered a great deal of attention in athletic training, as it has been directly linked to retention in the field.17,18,22,23 Athletic trainers are not alone in their struggles to find work-life balance; Americans in general are struggling to find it even as they work longer hours than people in other industrial countries.24

Health care professionals, and ATs in particular, are susceptible to reduced work-life balance because of demanding jobs that require long work hours, attention to patient care needs, and other duties, including administrative tasks, supervision of students, and travel.18,23,25–28 Organizational, or work environment factors (eg, work hours, scheduling), are most notably linked to a reduced work-life balance for the AT, although the setting can also serve as a direct contributor. We know that ATs blend personal and professional strategies to balance their multiple roles (eg, time management, work-life integration). Athletic trainers are employed in a diverse array of practice settings, and although organizational influences can affect the achievement of work-life balance, our hope is to discuss global recommendations as a means to promote balance.

The purpose of our position statement is to illustrate the concept of work-life balance and those factors that influence it and to provide recommendations to facilitate work-life balance in athletic training practice settings. Our recommendations are based not only on the available peer-reviewed materials within athletic training but also on other employment settings as well as the experiences of practitioners who are currently managing their work and life responsibilities in those settings. Consistent with other NATA position statements, we used the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) criteria29 as a framework for grading the strength of each recommendation. Because this topic affects practitioners rather than patients, we broadened the orientation of evidence to include practitioners. The vast majority of the literature related to work-life balance is observational studies and represents level 3 evidence in the SORT. The recommendations are designed to facilitate successful navigation of challenging work environments and promote work-life balance, but they are not a substitute for appropriate and necessary consultation with a mental health care provider.

The NATA suggests the following guidelines for recognizing and managing work-life balance in the athletic training population. These strategies and recommendations are presented from both the organizational and individual perspectives, as the literature in the work-life interface has recognized that this concept is not unidimensional. We know that specific individual (eg, gender, personality, family structure) and organizational (eg, work hours, job stress, work scheduling) factors are present, but each factor, regardless of level, may influence multiple outcomes. Work and family do not exist in a vacuum of individual or organizational reality, and these recommendations are designed to avoid placing all of the onus on the individual.

In the SORT, the letter indicates the consistency and evidence-based strength of the recommendation (A has the strongest evidence base). For the practicing clinician, any recommendation with an A grade warrants attention and should be inherent to clinical practice. Less research supports recommendations with grade B or C; these should be discussed by the sports medicine staff. Grade B recommendations are based on inconsistent or limited controlled research outcomes. Grade C recommendations should be considered as expert guidance despite limited research support.

Workplace Strategies and Recommendations

Practices for the Supervisor or Administrator

-

1.

Develop and communicate work-life policies that are viewed as gender, marital, and parent neutral. Such policies should include (1) personal leave (eg, sick leave, vacation, or time to attend continuing education opportunities) and (2) patient-care coverage (eg, hours of operation, traditional versus nontraditional season coverage, travel expectations, and medical coverage for practice and event changes with appropriate advance notice). All members of the sports medicine staff, coaches, and administrative members should be aware of and have access to these policies. Moreover, policy development should reflect the mission and vision of each sports medicine staff, department, and workplace setting.17,22,25,27,29–32 Strength of recommendation (SOR): C

-

2.

Enhance communication between the athletic training staff and administration by holding regular meetings. Coaches and leaders from each department or division should be present at these meetings. Agendas should be established before each meeting with consideration given to topics suggested by the coaches and department leaders. The needs of individual departments will dictate how often these meetings should occur, but we recommend the beginning of each sport season at minimum.31,33–37 SOR: C

-

3.

Assess each staff member's workloads and needs individually. The supervisor's assessment must be fair, consistent, and open to suggestions for improved work-life balance.29,30,33,34,37–39 SOR: C

-

4.

Establish a formal mentoring program for newly hired ATs to help them develop healthy and appropriate work-life balance practices. Mentors can be within the institution (ie, collegiate setting) or at peer or sister companies or organizations (eg, rehabilitation outreach or hospital). Informal mentoring is helpful, but consider assigning a more experienced employee, either within or outside the organization, to the newly hired staff member to help facilitate role inductance and on-the-job learning. Create program guidelines to encourage mentors and mentees to meet regularly and establish a connection. The perception of institutional support is essential for any successful mentoring relationship, and group mentoring (mentoring throughout the organization or department) enhances the effects of mentoring.22,40–44 SOR: C

-

5.

Encourage and promote modified job sharing (ie, teamwork) among athletic training staff members. Although traditional job sharing involves 2 or more individuals managing the workload for 1 job, modified job sharing creates a work environment in which other ATs cover events when the primary AT is not available because of a personal emergency or an event such as a wedding, a child's recital, or a day off. Modified job sharing can facilitate medical coverage during both emergency situations and normal day-to-day operations. Moreover, it facilitates team building and a family atmosphere among the staff. Job sharing is also recommended during summer coverage in the college or university setting. Consider having 1 central athletic training clinic open for all sports, covered by the athletic training staff in shifts. This will encourage employees to take time off and give them a chance to rejuvenate before the upcoming season(s).26,33,34,37,38,45–47 SOR: C

-

6.

Provide social and emotional support for employees when needed. Supervisors and administrators are the gatekeepers for ATs in their pursuit of work-life balance. Supervisor support promotes the perception of being valued and recognition that the needs of the AT extend beyond the workplace. Adherence to and facilitation of workplace practices related to work-life balance should be acknowledged, both formally (eg, maternity and paternity leave, sick leave) and informally (eg, afternoon off, modified job sharing, reduction in assigned responsibilities). The supervisor may be able to identify which policies and strategies can be implemented and used to help individual staff members find work-life balance.30,33,37,38,45,47,48 SOR: B

-

7.

Recognize and reward the efforts of staff members. Examples include offering unexpected time off, a reduction in workload, or increased control over work scheduling by providing autonomy to schedule treatment times and other duties related to their roles within the sports medicine department. Even a simple “thank you” goes a long way.36,49,50 SOR: C

-

8.

Model and practice effective work-life balance. Supervisors who demonstrate a commitment to their own work-life balance encourage the collective pursuit of balance among the staff, which improves the workplace atmosphere and promotes an environment that is viewed as family friendly.36,37,49,51,52 SOR: C

-

9.

Establish a cohesive workplace environment by hosting employee functions such as holiday parties or end-of-the-year celebrations as a time to reflect on and celebrate both work and nonwork accomplishments.31,38,50,53 SOR: C

-

10.

Encourage employee disengagement from the workplace as a means to rejuvenate and recharge from the demands of the professional role. For example, encourage ATs to leave for the day when the job responsibilities are complete.31,33,36,38,50,52,54 SOR: C

-

11.

Provide time and compensation for staff members to attend professional conferences as a way to support continuing education, professional networking, and rejuvenation.50,55 SOR: C

-

12.

Allow for workplace integration (ie, work-life integration) when appropriate. Recognition that an AT must satisfy both job demands and personal needs and responsibilities can help to reduce the mismatch that might result. Promote an environment that, when appropriate, permits bringing the children, spouse, or partner or other outside responsibilities into the workplace (eg, paying bills during lunchtime, family traveling with the team to away contests, including a travel companion).31,36,52,54,56,57 SOR: C

-

13.

Advocate for higher salaries for clinicians that correlate with job responsibilities and time demands and lead to perceived salary equality and employee satisfaction.13,46,58–61 SOR: C

-

14.

Campaign for more full-time staff members as a way to reduce workloads placed on the ATs and actively meet the NATA's “Recommendations and guidelines for appropriate medical coverage of intercollegiate athletics.”42,62–65 SOR: C

Practices for the Individual in the Workplace

-

15.

Set boundaries in the workplace. Unless it is an emergency, impose limits on coaches and student-athletes or patients as to when they can contact you (eg, no texts or phone calls before 6 am or after 8 pm). Clearly define what constitutes an emergency. These boundaries should be clearly communicated to coaches and patients during team meetings. Maintain these boundaries and evaluate their effectiveness often.31,33,39,48,54 SOR: C

-

16.

Prioritize daily responsibilities and tasks that include both personal needs and professional obligations, such as treatment hours, practice coverage, and time to engage in a relaxing activity.31,33,34,50,54 SOR: C

-

17.

Communicate effectively with all staff and administration. Supervisors and individual ATs should clearly explain medical-coverage expectations and policies to coaches, student-athletes, and athletic administrators.31,33,34,37,45 SOR: C

-

18.

Create both personal and work-related goals and proactively plan your calendar around those goals. Have a strategy that is proactive, not reactive. Be a mindful, proactive planner who makes time for both personal and work-related responsibilities.31,33,36,54 SOR: C

-

19.

Negotiate your role and opportunities as they unfold. Self-reflection on your role and time demands is critical to achieving balance. Use the strategic no or delegate responsibilities to create structure and boundaries and prioritize daily responsibilities.31,34,49,52 SOR: C

Non-Workplace Strategies and Recommendations for the Individual

-

20.

Disengage from your role as an AT to promote personal and professional rejuvenation. Personal time must be available regularly and be scheduled into daily planning. View your daily personal time not as a routine but as a ritual. Downtime during the day, vacations, and days off during the week can help you reenergize.31,33,34,46,50 SOR: C

-

21.

Create and use support networks that include peers, family, and friends. Be willing to ask for help when you need it and learn to recognize when you are becoming overwhelmed.17,31,33,34,52 SOR: C

-

22.

Develop healthy lifestyle practices such as daily exercise, eating healthfully, obtaining consistent sleep, and engaging in personal hobbies.31,33,34,38 SOR: C

-

23.

Separate your work roles from your personal roles. This separation can help you devote more time and energy to your nonwork roles, which in the end can improve satisfaction with the time spent in those activities. Commit to invest your time in 1 role at a time (eg, when at home, silence your phone and focus on your children, friends, and spouse or partner).17,31,33,34,38,54 SOR: C

-

24.

Be a team player. Promote and support the concept of modified job sharing in the workplace. This can create flexibility in work scheduling and improve the cohesiveness of the workplace culture. When an AT is the sole medical care provider, consider other ways to establish flexibility—using paid sick or vacation time, budgeting for a per diem AT to provide patient care when necessary, or tapping professional networks (eg, other high school ATs in the area) as ways to address patient-care needs when required.17,22,31,33,34,52,65,66 SOR: C

-

25.

Adopt a work-life enrichment philosophy as a means to achieve work-life balance. Positive experiences in 1 role can enhance the quality of life in another role. Individuals who are satisfied with work and personal roles experience greater overall wellbeing.47,67–69 SOR: A

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Definitions of Work-Life Balance and Work

The phrase work-family balance covers only those individuals who have traditional family responsibilities, such as commitments to a spouse, partner, or child, and has thus traditionally omitted single or unmarried professionals. The concept of work-life balance is an acknowledgment that one's work life and personal or family life may exert conflicting demands.32 Work-life balance reflects those practices used to facilitate the successful fulfillment of the responsibilities associated with all the roles one may assume, including parent, spouse, partner, friend, and employee. Individuals' personal lives vary based on factors such as age, relationship or marital status, and children. Personal interests, hobbies, activities, family involvement, social events, and other aspects of one's life outside of work also factor into an individual's personal life. Work-life balance represents the prioritization between work and lifestyle and should be interpreted as a positive concept. It is a state of equilibrium attained between an individual's primary priorities of his or her employment position and personal life70 and describes the magnitude to which an individual is equally involved in and equally content with the work and personal roles. Fereday and Oster27 defined work-life balance as the ability of people to accomplish what they consider most important. If work-life balance is attained, the burdens of an employee's career do not overpower the ability to enjoy a rewarding personal life outside of the business or organizational environment. Although this balance implies equity, it simply describes satisfactory levels of involvement among the multiple roles in a person's life.3,8 Our ability to define work-life balance is critical, as it is an overarching theme of all work relationships related to family, home, personal interests, and professional goals.8

American Work-Life Balance

Work-life balance has become a main concern for working Americans, who are reported to work more hours than people in other industrialized countries.24 Health care professionals, especially ATs, are notorious for working 40+-hour weeks. The 40+-hour work week involves many competing demands and expectations, such as patient care, supervision of athletic training students, administrative paperwork, and communication with coaches and other members of the sports medicine staff. The time demands associated with the role of the AT, coupled with the job demands and expectations, put ATs at risk for experiencing conflict. Work-life conflict has been reported in several athletic training settings, including college,5,7,19,45,46 secondary school,5,10 and clinic outreach.47 Although many of the antecedents to the conflict are shared, each practice setting has its own set of mitigating factors, which may affect the time the AT has available to address nonwork responsibilities and personal interests. Emotional conflicts may arise when competing demands are placed on an individual in the fulfillment of his or her multiple roles.51 Role theory69,71 predicts that the multiple roles individuals fill as workers and family members are in conflict with each other because of the inadequate amount of time and resources available to spend on each role. In essence, the time and energy spent in one role take time and energy away from the other roles, and this dilemma creates conflict.

Work-Family Conflict

Work-family conflict stems from the unharmonious emotional and behavioral demands of work and nonwork roles, such that involvement in one role is made more difficult by participation in the other.48 Predictably, the more we fight for work-life balance, the more work-family conflict occurs. The manifestation of work-family conflict can lead to strain between work and family roles, which can become a stressor that diminishes psychological and physical wellbeing.45 Consequently, today's increasing participation of women in the workforce, in addition to a greater number of dual-earning couples, has led to more work-family conflicts.

According to the literature,45 activities in daily life that add to work-family conflict are job expectations and responsibilities, emotional involvement in one's job, inflexible requirements, and significant job demands. Nelson and Tarpey39 reported that individuals without a choice or input in setting their work schedules or hours may be more predisposed to work-family conflict. Previous authors45 emphasized that workers subjected to stressor agents incurred increased costs for their organization associated with inefficiency, absenteeism, turnover, and reduced job satisfaction and productivity. Other negative health effects of work-family conflict described by Pisarski et al48 were anxiety, depression, burnout, somatic complaints, elevated cholesterol levels, and substance abuse.

Theoretical Background

Six models or perspectives are often used to articulate the relationships among work, family, and life: segmentation, integration, spillover, compensation, instrumental, and conflict.56,57 The Table describes each model and provides an example in the context of athletic training.

Table.

Work-Life Balance Concepts

| Model |

Defined |

Example |

| Segmentation | A model of 2 distinct domains of life, such that no influence is experienced from one role to another56,57 | The AT does not respond to e-mails or text messages or address administrative tasks when not at work, and, vice versa, does not address family or personal needs while at work. The AT can create and maintain certain work hours during the week. |

| Integration | Work and life are interchangeable roles. Work-life integration challenges the traditional mindset that work responsibilities can only be completed during the workday and that personal and family obligations are done after the workday or on the weekend.56,57 | The AT may use downtime during the day to work out or have lunch with a spouse, or may respond to e-mails and complete injury updates at home once parenting responsibilities have been completed. |

| Spillover | The effect that one role can have on the other, such as how the load placed upon the employee in the workplace can influence, negatively or positively, the completion of responsibilities in the other roles54,55 | The AT may be at home, eating dinner with family, when an emergency arises and he or she must go to work or, at minimum, manage the situation. |

| Conversely, an AT may gain patience in dealing with student-athletes because he or she deals with small children at home. | ||

| Compensation | The premise that what is lost in one role can be supplemented in other roles54 | A part-time, paid work position allows for more time at home with children, or, in contrast, an AT assumes a higher-paid position to provide financially, despite having less time available at home. |

| Instrumental | Success in 1 role facilitates successes in others, such as working hard, long hours to purchase a new home or car54 | An AT who is promoted to associate or head AT receives a pay increase and is able to provide more for family. |

| When an AT can bring family on road trips, they share the experience and spend more time together. | ||

| Conflict | An individual has high demands in all aspects and often becomes overloaded, resulting in conflict among roles | An AT who provides medical coverage for 2 sports with conflicting seasons, serves as a preceptor, and has young children at home may be susceptible to conflict. |

Abbreviation: AT, athletic trainer.

Many of these models provide the foundation for strategies used to reduce or manage work and life responsibilities. The concepts of segmentation and integration, for example, have been discussed in the literature as ways to facilitate balance, although by very different means.54 In contrast, work-life segmentation occurs when borders are created between work and life roles; blocks of time are devoted to completing the tasks of each role, without allowing them to influence one another. Work-life integration strategies address the intersections among work, family, and life, and the expected overlap. The 2 theories are dichotomous; because they offer different ways to create a balance, the individual must decide when to apply each. In fact, within athletic training, the 2 theories are often both used as ways to promote more family time and decompress from the strain of the workday.25

Antecedents of Work-Life Conflict

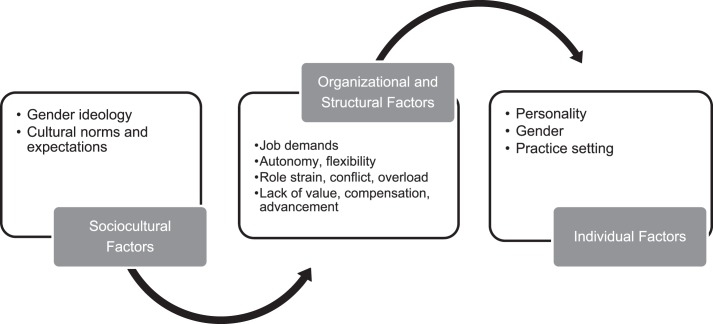

Experiences of work-life conflict have often been presented in a 2-dimensional model, where work and family demands lead to conflict. Working hours are generally the most predominant imbalance factor in the working sector, whereas parenting duties, caregiver duties (ie, caring for a parent or child), and household maintenance constitute the bulk of family demands. However, Dixon and Bruening72 suggested that conflict manifests because of an interaction of 3 factors: organizational, individual, and sociocultural. Organizational factors represent working hours, work schedules, and job dynamics such as travel, flexibility, and face time.72–74 Individual factors epitomize a person's values, beliefs, and preferences regarding work, home, and lifestyle choices. Experiences of work-life conflict may be affected by personality, gender, and coping or support systems. One's career path or choice can be influenced by a preference for work-life balance, which ultimately affects the job selection. The Dixon and Bruening72 model depicts that experiences of work-life conflict can be stimulated by organizational factors for all those working in the same setting, yet management of those variables can vary for the individual. Valuing family and work and trying to create equity between the two is often a source of stress for the individual working in the sport context.72,74 Thus, experiences of work-life conflict appear to be personal and based on individual preferences regarding the amount of time invested in one role versus another. Sociocultural factors reflect the social meanings of work and family. Historically and stereotypically, it was thought that women chose family over work, or at best, they struggled more to balance demands because they felt greater responsibility for domestic needs, child care, and household duties. The relationship among these 3 facets can influence one's experiences with work-life balance. An illustration of the model, as adapted to the profession of athletic training, is presented in the Figure.

Figure.

Modification of the work-family interface as originally described by Dixon and Bruening,74,75 highlighting the multilevel factors that can affect individuals' perceptions of satisfaction in their work and personal lives.

The literature highlights the burden work demands can place on the AT, thereby facilitating conflict between work and home lives.17,22,23,26,65 Within athletic training, organizational and structural factors appear to be the greatest facilitators of conflict. These factors are summarized as job demands, lack of autonomy over work scheduling, role strain, requirements of the work setting, perceived reduced value, and inadequate compensation. Gender and practice setting also contribute to work-life conflict in athletic training. We will discuss each item.

Job Demands

Key job demands for ATs include hours worked and travel associated with the position. Similar to the work of Dixon and Bruening72–75 and Dixon and Sagas76 within the coaching and sport management literature, the excessive time commitment and necessary travel to do the AT's job present challenges to performing normal day-to-day activities in addition to allocating time for leisure and family responsibilities. On average, an AT works 40+ hours per week, excluding time spent traveling.23,31 In some cases, ATs reported working 80+ hours per week because of time spent evaluating and treating patients, travel, and administrative duties associated with patient care.6,16 Mazerolle et al23,31 found that the average in-season work week for an AT in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I setting was 63 hours per week, reflecting a reduced amount of time available for nonwork-related responsibilities and interests. As suggested by Bruening and Dixon,73 excessive time demands have become institutionalized within the athletic world and are often synonymous with commitment and productivity. To demonstrate commitment and success, ATs may assume the mindset of needing to be available and present at all times. This often manifests as an AT being assigned to provide health care to 1 or more teams and then that AT's becoming the sole provider of services to patients on those teams, so that when those teams are practicing, conditioning, or receiving treatments, the assigned AT is the only individual who can provide patient care. When the AT lacks control over activity scheduling, long hours often ensue and the AT is compelled to be available.

Conflict due to work hours is mitigated in the clinical practice (industrial or clinical rehabilitation) setting by a more structured, 40-hour work week.65 Time-based conflict is the underpinning of conflict for any working professional, as often one role depletes the time available for other roles. This conflict is illustrated by the job demands of working as an AT.

Autonomy and Flexibility

Although excessive work hours and travel are the most often reported antecedents of conflict, the idea of face time, as coined by Dixon and Bruening,74 can be another structural aspect of the profession that contributes to work-life conflict for the AT. Face time is the need to be present in the workplace to complete the responsibilities and expectations of the role. Similar to other health care professionals, ATs must be available to provide medical care to their patients, which requires them to be in the workplace regularly and often. The expectations placed on the AT, particularly in the collegiate setting, to be present and always accessible for the patient have been cited as a structural factor contributing to work-life conflict.31 Personality is often linked to experiences of conflict,74,77 and even though the reports are anecdotal, ATs have frequently been described as conscientious and agreeable, traits that can lead to conflict when patients' needs are placed above their own. Expectations of the organization and those within it to be ever present can create the potential for conflict and especially work-life conflict.

The concept of workplace flexibility has catapulted to the forefront within organizations and in the literature as a critical strategy to reduce problems with work-life balance. Each year, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation honors organizations for effectiveness in workplace flexibility.78 Workplace flexibility options often include approaches such as telecommuting, compressed work weeks, and autonomy over work scheduling. However, these options are typically not possible in the athletic training workplace. Therefore, face time74 is often necessary to fulfill the requirements of the job. In the secondary school setting, Pitney et al26 found that ATs who had workplace flexibility experienced less work-life conflict than those who did not have control over their work schedules. Similarly, the concept of workplace flexibility, in regard to scheduling, mediates the experiences of work-life balance for the AT in the outreach-rehabilitation65 and collegiate settings.18,23,30 Job sharing, a workplace practice designed to create flexibility for the working individual, has been modified for use in athletic training to provide flexibility where it is not traditionally afforded. Coworkers rely on teamwork to provide time off to manage nonwork responsibilities, thereby fulfilling the requirement for face time.74 Job sharing, whether in its original or modified approach, has gained popularity as a work-life strategy, but it is a mindset that may require adjustment for ATs, who commonly take ownership of the care they provide to their student-athletes. Yet the approach can be thought of as comparable with that of a substitute teacher, who for 1 day facilitates the lesson plan (ie, treatment plan or prepractice and postpractice routine) in the absence of the teacher (ie, AT).

Role Strain

Balancing the domains of work and life is an expected aspect of our professional adult lives.79 Failure to balance these aspects results in many negative personal and professional outcomes. A great deal of research has been conducted to identify the antecedents of work-life conflict, one of which is occupational role strain.6,16,17

Occupational role strain, which we will refer to as role strain, has long been identified as an antecedent to work-life conflict.79 Role strain is defined as “a subjective state of emotional arousal in response to the external conditions of social stress” and occurs when one's “role obligations are vague, irritating, difficult, conflicting, or impossible to meet.”80(p165) Essentially, role strain occurs when the various obligations an individual has in an occupational role are difficult to meet.71,81

A strategy to help ATs reduce their role strain is to enable them to better acclimate to the profession. This can conceivably be done through professional socialization, role modeling, and mentorship. Professional socialization is a process by which individuals learn the knowledge, skills, values, roles, and attitudes associated with their professional responsibilities.82 Two studies examining the effects of professional socialization among high school83 and collegiate84 ATs highlighted the informal nature of the process and its importance in role evolution. The concept of mentoring was explained by Levinson85 in the late 1970s and described as one of the most significant relationships an individual can have in early adulthood. Mentors are senior members of a group who intentionally encourage and support younger colleagues in their careers86 and often provide role modeling. A role model teaches predominantly by example and helps to form an individual's professional identity and commitment by promoting observation and comparison.86 Role modeling is less intentional, more informal, and more episodic than mentoring.

Role strain comprises 5 components: (1) role overload, (2) role conflict, (3) role ambiguity, (4) role incongruity, and (5) role incompetence. Role overload occurs when the role expectations are too time consuming.63,87–90 Role conflict occurs when role expectations compete with one another or when the expectations are incompatible, meaning that it is difficult to achieve 1 role when attending to another within a role set. Role conflict is further subdivided into intersender conflict, intrasender conflict, and interrole conflict. Intersender conflict arises when 1 individual's demands interfere with another's within an occupational setting, whereas intrasender conflict results when one feels competing demands to adequately fulfill multiple roles. Interrole conflict relates to finding it difficult to fulfill multiple roles simultaneously.80 Role ambiguity occurs when the role expectations are unclear.63 Role incongruity results when the disposition of an individual is incompatible with the expectations of a given role.80 Lastly, role incompetence is the consequence when an individual lacks the requisite skill or knowledge to execute the demands of an occupational role.80 Role strain leads to work-life conflict when an individual's performance in 1 domain (eg, home) is impaired because of the increased emotional stress brought on by the role strain incurred in the work domain.79,91

Role strain is an antecedent of work-life conflict due to negative spillover.92 Negative spillover describes the negative effect of work on one's participation in the family or personal domain.93 Although various types of spillover from work to personal life exist, negative work-to-family spillover is related to exhaustion and psychological distress.93

Research in athletic training has identified common forms of role strain experienced by ATs. Pitney et al94 found that role overload, role conflict, and role incongruity were the most prominent components of role strain experienced by ATs who were also educators in the secondary school setting. In their study, the number of hours worked per week was the only predictor of role strain. Corroborating these findings, Henning and Weidner81 investigated role strain among preceptors in the collegiate setting and noted that role overload was the most prominent form of role strain. More recent research23 into work-life balance has also shown that role overload (ie, a high number of hours worked per week) was connected with work-family conflict. Previous investigations23,74,79,95,96 have revealed a link between role strain and work-family conflict; specific to athletic training, there is strong evidence for role overload permeating the workplace.

Role Overload

Greenhaus and Beutell91 originally discussed work overload as a time-based antecedent of work-family conflict; consistent with athletic training, long work hours interfere with the family domain.87 However, another dimension of time-based work overload involves schedule requirements (eg, working mornings, evenings, weekends, or odd hours) and scheduling inflexibility (eg, having little control over one's schedule).87,91 The lack of both schedule control and schedule flexibility are antecedents to work-family conflict,23 can affect the individual's workload, and are precipitating factors in role strain.

Role Conflict

As Michel et al79 noted, role conflict is an antecedent to work-family conflict, and indeed, Greenhaus and Beutell91 found higher levels of work-family conflict associated with high levels of role conflict. Moreover, role ambiguity and role overload have also been linked to higher levels of work-family conflict.62 When an individual incurs role strain, more psychological and physical energy is spent on the roles in that domain, leaving less energy to attend to the roles in another domain.79

Role Ambiguity

Role ambiguity refers to a perceived level of uncertainty related to one's responsibilities within an organization and what colleagues expect.88,89 The ambiguity associated with one's role is often the result of a lack of information or ineffective communication,33,34 resulting in a lack of clarity as to what a supervisor expects.35

Role ambiguity, like other forms of role stress, is related to negative outcomes such as depression and anxiety.89 Furthermore, role ambiguity can increase emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and decrease personal accomplishment, which are all components of burnout.90 Because of spillover, role ambiguity also influences an individual's personal life and has been correlated with work-life conflict.95,96

Lack of Perceived Value

The word value has different meanings based on the context (eg, economic, marketing, personal, ethical, or cultural). In The Oxford Dictionary,97 the first definition of value is “the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something.” An AT's perceived value might be defined as the perceived respect, importance, worth, and usefulness of the AT in a particular position, organization, or setting. For decades, ATs have worked to establish and distinguish their value in health care and the many different organizations with a health care component (eg, secondary schools, colleges and universities, military, professional sports). In recent years, ATs have even had to fight for the right to practice certain skills, such as manual therapy.98 Respect, recognition, and organizational commitment are primary reasons for retention of health care professionals.99 Similar to other health care professionals, ATs want to be respected and recognized for their skills and contributions to their organizations and patients.

This perception of value starts with our future—athletic training students. Heinerichs et al100 reported that one factor responsible for athletic training students' high levels of frustration in their clinical education experiences was the perceived lack of respect from coaches and student-athletes. Mazerolle et al14 found the perceived lack of respect for the profession, lack of adequate compensation, high level of job demands, and usefulness of the athletic training degree as a precursor to another health care degree influenced the decisions of recent athletic training graduates to not pursue a career in the profession. Newly certified ATs who seek to advance their athletic training knowledge through accredited postprofessional athletic training programs appear to demonstrate a commitment to the profession. However, in a 2015 study,13 a perception that ATs' professional and personal lives were lacking in value was a primary reason why graduates of these programs chose to leave the profession.

Collectively, low salaries, the AT's work schedule—affected by administrators, supervisors, and coaches—and an inadequate number of staff ATs employed by an organization contribute to an overall perceived lack of value among ATs.13,17,23,33 Ultimately this contributes to work-life conflict, job dissatisfaction, and attrition.13,17,23,33 The NATA and ATs themselves have advocated for recognition, value, and improved employment conditions. The college value model15 was created by members of the NATA's College/University Athletic Trainers' Committee. This publication was designed to assist ATs in maintaining or improving their professional positions by quantifying their worth to their organization through documentation of medical services and outcomes, risk management, organizational and administrative value, cost containment, and influence on the student-athlete's academic success. The committee's hope was that the model will serve not only as a tool to improve the conditions (eg, salaries, benefits, workload) for current positions and create more jobs but also as an educational tool for athletic training educators to provide students with a clearer image of an AT's value in health care. The NATA Secondary School Athletic Trainers Committee has created a similar secondary school value model.16 This publication quantifies and articulates why ATs are vital health care service providers. The NATA's “Recommendations and Guidelines for Appropriate Medical Coverage of Intercollegiate Athletics”64 provides collegiate ATs with a system for evaluating their current level of medical coverage. Although the recommendations were primarily created with student-athlete safety in mind, they can also assist collegiate ATs in assessing workload and staffing. The “Secondary School Position Improvement Guide”101 is another publication of the NATA's Secondary School Athletic Trainers' Committee. This document is intended to assist secondary school ATs in improving their current employment situations through recognition, documented improved care, accountability, and budget-conscious strategies. In addition to guidelines and recommendations for ATs in secondary school and collegiate athletics, the NATA has formulated leadership-development programs to assist ATs in creating, improving, and refining their leadership skills so that they can help promote and lead the profession. Although these efforts are steps in the right direction toward increasing ATs' recognition, respect, and perceived value, researchers have found this perceived lack of value, especially in the areas of promotion or advancement and compensation, to be an important concern in athletic training.

Lack of Promotion or Advancement

More chances for promotion or advancement have positive effects on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intent to stay.102 A lack of such opportunities in an organization is an established attrition factor for ATs,103 especially in the collegiate setting.17,66 Terranova and Henning104 demonstrated that advancement was one of the best predictors of job satisfaction and intent to leave among collegiate ATs. The structure of most college and university athletic training staffs and the departments in which they are housed do not cultivate promotional and advancement opportunities, and the number of positions available in a collegiate institution is limited. A study66 of male ATs formerly employed in the NCAA Division I setting revealed that lack of advancement was a major departure factor. In most instances, the AT had no opportunity for vertical advancement from the title of assistant AT unless he or she waited for the head AT to take another job or retire. Few advancement opportunities also exist in the professional and secondary school settings, although research in this area is limited.

Lack of Compensation

Adequate compensation has been a longstanding concern in athletic training and a known attrition factor.13,38,66,103 Specifically, low salaries for the number of services and the amount of time given to provide those services have long been cited. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics105 projected 30% growth in ATs from 2010 to 2020, much faster than average job growth, although ATs were listed in conjunction with exercise physiologists. Furthermore, US News & World Report106 described athletic training as one of the best careers of 2011. However, in that same year, CNN107 named the entry-level athletic training degree as one of the top “college degrees that don't pay,” and Yahoo108 placed athletic training fourth on the list of 20 worst-paying college degrees. In 2011, the NATA109 reported athletic training salaries had risen in almost every category over the last 3 years. Average earnings were $46 176, $51 144, and $76 262 for a bachelor's, master's and doctoral degree, respectively. Five years later, the 2016 NATA salary survey110 reported average earnings of $48 498, $54 695, and $81 921 for bachelor's, master's, and doctorate degrees, respectively, which may suggest a trend toward salary increases. Athletic training salaries have increased over the years; the 2016 average bachelor's degree earning was just above the US Bureau of Labor Statistics May 2017 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates national earning ($46 230).111 According to the 2016 NATA salary survey, the average AT's earning (regardless of degree) was $54 832, which was 35% lower than occupational therapists ($84 640), and about 37% lower than physical therapists ($88 080) according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2017.108

Salaries are improving, but the perception of increased compensation is not improving quite as fast. Not only were recent athletic training graduates concerned about work-life conflict in the profession, they were also concerned about low compensation.60 Both current and former ATs have expressed that their decision to leave certain athletic training settings or the profession entirely was influenced by a lack of compensation.13,66 The combination of long hours, low compensation, and lack of advancement can influence perceived value, organizational commitment, and longevity. Low compensation levels have been positively correlated with work-life conflict.112 However, low pay alone may not directly result in work-life conflict unless an employee is dissatisfied with pay and also believes there is an inequity; employees who were satisfied with their pay reported higher levels of work-life balance.113 Thus, adequate pay should be a component of a program designed to mitigate conflict and facilitate work-life balance.

Demographic Influences

Gender

Generally, working females have more trouble balancing their career demands and family responsibilities, largely because of mothering philosophies and traditional gender stereotypes.17 Remarkably, gender differences have not been found in the manifestation of conflicts between work and personal life in the athletic training profession.18,23 Yet female ATs have changed careers or clinical settings to strike the coveted work-life balance.17,18,22,23 Mazerolle et al18,23 observed that only 22 women with children were employed in the NCAA Division I collegiate setting. Although these numbers may have increased since the study was conducted, they are likely still low. In 2014, the percentage of women in head athletic trainer positions in collegiate athletes increased to 32.4%, but a small percentage (19.5%) was employed in Division I.113 More data are needed to better understand employment opportunities for women at the collegiate level and the struggle to balance professional responsibilities with parenthood as related to the retention of female ATs.22

People vary in their experiences of work-life balance and their ability to cope because of differences in individual characteristics (eg, gender).59,77,114–116 Often the negative effects of work-life conflict come from internal feelings of conflict. Differences at the individual level can be particularly evident when examining people in the same or comparable positions, such as assistant AT or high school AT. For example, athletic training positions can be similar in the types of role strain faced by employees: Naugle et al117 determined that female ATs reported more frequent burnout than their male counterparts, even though the men worked, on average, more hours than the women.

Gender concerns do exist in the profession of athletic training. Athletic training has traditionally been viewed as a male-dominated profession; however, membership statistics now show a shift, indicating an equal number of men and women in the profession.118 The preponderance of pressure, professionally and personally, that female ATs experience comes from family demands rather than work demands, especially when the family includes children. Women account for 50% of the athletic training workforce, and 81% of women desire to parent or participate in parenting.22 Barriers for female ATs are associated with gender equity and work-life balance challenges, particularly in the Division I setting.17 Female ATs have identified the time commitment of the profession, particularly in the collegiate setting, as problematic, especially when trying to balance motherhood and athletic training.17,22,23,25 Though gender has been linked to work-life conflict in other professions and anecdotally in athletic training, it has not empirically been documented as playing a role in experiences of conflict for the AT. Male ATs acknowledge work-life conflict as a potential departure factor, but role strain and the lack of advancement opportunities had greater influences on reasons to depart.66

Hakim119 suggested that women's positions in the workforce and in the family are an expression of their own preferences and not social constrictions. Preference theory, as developed by Hakim,119 speaks to the idea that individuals, and women in particular, can choose their work-lifestyle preferences once genuine choices are available to them. Furthermore, the theory contends that a woman's preference is based on her personal needs and goals, which are likely independent of factors such as societal contentions or organizational views.

The preference theory model describes 3 possible preferences: work centered, adaptive, and home centered.120 Mazerolle et al121 found that choosing a career over starting a family may help the female AT succeed in the role of head AT, indicating that preference was occurring in the profession. Even when married, work-centered women focused their family lives around work, with many staying childless. Preference theory predicts that men will maintain supremacy in the labor market because of the minority of women who are work centered and willing to prioritize their jobs.119 Adaptive women favor combining family and careers without assigning a priority to either; they fundamentally want to enjoy the best of both worlds. This preference has been suggested as influencing the decisions of female ATs regarding career choices, particularly with respect to not moving up the administrative chain. Hakim119 proposed that most women fall into the adaptive category, seeking a balance between work and home. The third group, home centered, prefers to give precedence to their families after they marry. Though anecdotal, it is conjectured that most female ATs favor an adaptive lifestyle, whereas those who seek administrative and leadership roles may exhibit a more work-centered mindset.121,122

Work Setting

Among the many athletic training work settings that have been investigated, the Division I setting has been the most studied in regard to work-life balance and retention.17,18,22,23,25,31,38,61,66,121 According to NATA membership statistics,106 the college and university setting employed 24.4% of members.110 The unique nature of work demands in this setting, combined with the dwindling offseason in collegiate sports, has prompted researchers to examine the professional and personal lives of collegiate ATs. Work environment and atmosphere, organizational commitment, increased autonomy, and enhanced social support systems highly influence retention in the collegiate setting.17,61 Successful work-life balance has been demonstrated in this setting,38 yet work-family conflict,18,23 organizational influences,41 and attrition17,66 are still prevalent.

Pitney et al26 found that work-family conflict was experienced by secondary school ATs, regardless of gender or family status. The number of hours worked and lack of scheduling control were the main factors affecting this perceived conflict. Mazerolle and Pitney65 investigated the work-life balance of ATs in the clinical rehabilitation setting and noted that organizational support and a more traditional work schedule strongly promoted a more balanced lifestyle. Eberman and Kahanov53 studied work-life balance and parenting perceptions and concerns in a nationwide survey of ATs and learned that the decision to have children was affected by work setting. Collegiate ATs felt most certain that their families were neglected because of work responsibilities. Compared with other settings, ATs in the collegiate and secondary school settings wanted to spend more time at home than they had been doing. This was likely due to the irregular, inconsistent hours often worked in these settings. The researchers observed that the clinic or hospital setting was the most tolerant of parenting responsibilities. However, overall, no employment setting was perceived to be very tolerant of parenting responsibilities.

Consequences of Work-Life Conflict

Growing evidence suggests that work-life balance is becoming harder to achieve and that work hours are just one aspect of the challenge. As discussed previously, the AT's work-life balance can become disrupted by a variety of factors, including organizational or structural and individual aspects.23,25,26,31,65 Continual conflicts can lead to a host of negative outcomes, and as outlined by Allen et al,123 they can be categorized as work-related, nonwork-related, or stress-related outcomes.

Outside of athletic training, work-family or work-life conflict has been associated with lower levels of job and career satisfaction and organizational commitment, intention to turnover, life and marital dissatisfaction, and more experiences of depression and burnout.123 For the AT, several outcomes have been documented, including job dissatisfaction, intention to turnover, and job burnout.18 In fact, Mazerolle et al18 showed that ATs experienced greater levels of job burnout and dissatisfaction than other professionals who experienced work-family conflict.123

Burnout

Job burnout, a condition that is characterized by emotional and physical exhaustion due to chronic stress, affects the AT.24 Like work-life balance, job burnout is often facilitated by organizational factors related to workload,2 organizational demands (responsibilities, hours worked, etc),5,7,54 and collegial relationships.112 Investigations5,6 of burnout began in the early 1980s, but it only become linked to work-life balance in 2008, when Mazerolle et al23 found that as levels of work-family conflict increased, so did burnout. The strongest relationships in the literature were between work-family conflict and job burnout.121 The condition can result from a variety of factors but notably because of hours worked,117,123 a predominant concern in athletic training. Giacobbi124 found that ATs were generally less burned out than health care providers in other settings. Moreover, he noted that many ATs likely possessed individual and contextual resiliencies, healthy behaviors that may mitigate burnout.

Burnout is described as a condition that manifests because of chronic stress and is hallmarked by emotional exhaustion.8 Exhaustion frequently results when an individual is unable to cope because of a lack of resources or coping mechanisms, often because he or she is unable to rejuvenate by getting away from the stressor.4,50 Consistently, hours worked have been identified as the precipitating factor for burnout,2,3,5,65 and in fact, Clapper and Harris,3 when developing an athletic training–specific survey instrument, found time commitment to be a predominant construct unique to the Maslach Burnout Inventory.8 In addition to time, administrative loads and organizational support and structure119 have emerged as antecedents to burnout, similar to work-life balance.31,38

Like work-life conflict, burnout in athletic training appears to materialize regardless of the clinical setting,54 as it has been reported in graduate assistant ATs,9 program directors,11 and those who work in the collegiate5,117 or secondary school setting.10 Lack of motivation, disinterest in previously rewarding activities, fatigue, and disengagement are signs of burnout that are expressed when the work environment is characterized as high pressure or time intensive or control over work scheduling is limited. Other factors that can contribute to job burnout include role overload, lack of sleep and exercise, and limited time available for leisure activities.12 The underlying factors contributing to burnout are analogous to those for work-life conflict, and a direct link between the 2 has been found in the literature123 and in athletic training.18 Of greater concern is the link between health-related variables and turnover with both burnout and work-life conflict.117,123 Although the literature is sparse, some evidence indicates that ATs have lower levels of physical activity and poor nutritional habits.125 Abundant evidence supports the connection between the constructs and departure from the profession.17,22,23

Job Dissatisfaction

Job dissatisfaction is the main predictor of intention to leave a profession or organization.126,127 A person with a higher level of job satisfaction is less likely to leave a profession than an individual with a lower level.127 Job satisfaction has been defined as the degree to which an individual likes his or her job128 and consists of an affective component (feeling satisfied regarding the job) and a perceptual component (whether or not the job is meeting the needs of the person).

Job satisfaction is a well-documented facilitator of organizational and professional commitment,129,130 especially in the nursing and health care fields. Concerns about attrition within athletic training have also gained attention in the literature as the constructs of job satisfaction and intention to leave have garnered much interest.23

Job satisfaction exists and has been investigated in every profession. Job satisfaction within the health professions has been a focus since an author131 examined the job satisfaction of nurses in the 1940s. Since then, job satisfaction has been studied in various health care professionals, including physicians,132 occupational therapists,133,134 and physical therapists.134–136 Initial research on job satisfaction in athletic training began in the 1980s with a look at burnout syndrome.4 Certain factors greatly influence job satisfaction within athletic training: for example, pay,137 work-family conflict,138 and organizational constraints.139 Each of these factors can positively or negatively affect the job satisfaction of ATs. Although increased pay and job recognition have direct positive relationships with job satisfaction,140 increased job stress and work-family conflict have direct negative effects on job satisfaction.62

Research on the nursing profession has highlighted a relationship between lower job satisfaction and increased intention to leave a profession.137 Terranova and Henning104 found a strong negative correlation between job satisfaction and intention to leave the athletic training profession. Additionally, they discovered that NCAA division did not affect an individual's job satisfaction or intention to leave the profession. Ongoing evidence shows that an AT's positive assessment of his or her job and career correlates positively with continued commitment to the organization.

Reduced Organizational Commitment

The outcomes of reduced work-life conflict have been of primary interest to researchers.141 When job satisfaction is reduced because of work-life conflict, a reduced commitment to the organizations in which ATs work is commonly noted. Organizational commitment is defined as a “strong belief in and acceptance of the organizational goals and values, willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization, and a definite desire to maintain organizational membership.”142(p604)

Organizational commitment is typically identified as having 3 components: affective, normative, and continuance.143 Affective commitment refers to an emotional identification with the organization; normative commitment relates to the feeling of obligation to continue with employment; and continuance commitment relates to the costs associated with leaving one's role in an organization. Affective and normative commitments are most relevant because of their predictive validity.141 Studies144,145 have consistently revealed a negative relationship between work-life conflict and organizational commitment. That is, as work-life conflict increases, the commitment one has to the organization decreases.

The relationship between work-life balance and organizational commitment can also be seen in work-family benefit utilization. For example, Thompson et al146 found that employees reported greater affective commitment when employed by organizations that provided work-life benefits such as flex time, telecommuting, and absence autonomy. Similarly, Allen147 observed more affective commitment in employees who perceived that their organization was supportive of family.

Turnover

In the employment context, turnover and attrition have often been used synonymously. Although these terms are similar, they are, in fact, different. Both turnover and attrition can be voluntary (eg, resignation, retirement) or involuntary (eg, firing, layoff). The difference is employee replacement. Turnover is the movement of employees within a certain position or across an organization or setting (or both)102: the rate at which an employer gains and loses employees (eg, an employee resigns and a replacement employee is hired). Attrition is a reduction in the number of employees for voluntary or involuntary reasons where the employee is not replaced.148 These vacated positions remain unfilled or are eliminated. In the organizational context, attrition has been used to describe ATs who leave the athletic training profession entirely. Since the 1950s, several research models for predicting employee turnover have emerged, and the general consensus is that multiple pathways to turnover exist. In the past decade, investigators have begun to emphasize (1) personality and motivational differences, (2) interpersonal relationships (eg, supervisor-employee exchanges), (3) intent-to-stay factors, and (4) dynamic modeling.149

In all organizations, a certain amount of turnover is necessary and inevitable.102 However, high turnover rates adversely affect organizational effectiveness, goal achievement, and quality of patient care.102,150 In light of the growing need for health care services and the specific growing need for ATs, AT attrition is certainly not desirable. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics105 predicted the athletic training profession will have a 21% increase in employment from 2012 to 2022. This change is larger than for registered nurses (19%) but smaller than for occupational therapists (29%) and physical therapists (36%). However, Kahanov and Eberman151 showed that the NATA had a general decline in members at the age of 30, with a marked decline in female ATs at age 28. Male AT representation in the secondary school setting increased, indicating a setting shift. Although this was a cross-sectional study of NATA membership, these results suggest an early exit from certain athletic training settings or from the profession entirely.

Turnover and attrition research is often difficult to perform, the primary reason being that participants are difficult to find or track once they leave a position, a setting, or the profession. Hence, little empirical research is available on actual AT turnover rates and attrition from an NATA membership or a Board of Certification perspective. Yet research on athletic training turnover supports the importance of addressing work-life balance in our profession, as factors of work-life conflict were the main reasons for leaving a setting or the profession of athletic training entirely. Capel103 examined AT attrition more than 28 years ago and noted that time commitment, low salary, limited advancement, and administrative and coaching conflicts were the primary reasons for leaving the profession. Goodman et al17 showed that female ATs decided to leave the NCAA Division I setting or the profession entirely because of work-life conflict, role strain (role conflict with supervisors or coaches [or both] and role overload), decreased autonomy, and kinship responsibility. Mazerolle et al66 reported that male ATs decided to leave the Division I setting or the profession because of work-family conflict, role strain (role conflict with administration or coaches and role overload), role transition (eg, phased retirement), and a lack of opportunities for career advancement (eg, promotional chances and raises). Bowman et al13 examined graduates of postprofessional athletic training programs who decided to leave the athletic training profession. The 2 primary reasons for departure were (1) decreased recognition of value, primarily based on low salaries and being overworked, and (2) work-life conflict.

CONCLUSIONS

The importance of work-life balance has become increasingly apparent as many ATs change positions or practice settings or leave the profession entirely because they fail to find or maintain it. Work-life balance is affected by many factors; however, the strongest constant predictor of conflict is the time spent at work. Other organizational factors can create challenges and influence an AT's perceptions and fulfillment of work-life balance. The pursuit of work-life balance must be both individual and collective. To facilitate work-life balance, we recommend deliberate planning, implementation, and evaluation of the strategies in order to monitor workplace outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Thomas G. Bowman, PhD, ATC; R. Mark Laursen, MS, ATC; Peter Giacobbi, PhD; Laura L. Harris, PhD, ATC; Diane M. Wiese-Bjornstal, PhD; and the Pronouncements Committee in the preparation of this document.

DISCLOSURES

Stephanie M. Mazerolle, PhD, ATC, FNATA; William A. Pitney, EdD, ATC, FNATA; Ashley Goodman, PhD, LAT, ATC; Christianne M. Eason, PhD, ATC; Scot Spak, MEd, ATC; Kent Scriber, EdD, PT, ATC, FNATA; Craig A. Voll, PhD, PT, ATC; Kimberly Detwiler, MS, LAT, ATC, CSCS; John Rock, MA, ATC; and Erica Simone, MS, ATC, have no disclosures to report. Larry Cooper, MS, ATC, is a member of the Korey Stringer Institute Scientific Advisory Board.

DISCLAIMER

The NATA and NATA Foundation publish position statements as a service to promote the awareness of certain issues to their members. The information contained in the position statement is neither exhaustive nor exclusive to all circumstances or individuals. Variables such as institutional human resource guidelines, state or federal statutes, rules, or regulations, as well as regional environmental conditions, may impact the relevance and implementation of these recommendations. The NATA and NATA Foundation advise members and others to carefully and independently consider each of the recommendations (including the applicability of same to any particular circumstance or individual). The position statement should not be relied upon as an independent basis for care but rather as a resource available to NATA members or others. Moreover, no opinion is expressed herein regarding the quality of care that adheres to or differs from the NATA and NATA Foundation position statements. The NATA and NATA Foundation reserve the right to rescind or modify its position statements at any time.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choksi DA, Shectman GS, Agarwal M. Patient-centered innovation: the VA approach. Health Care. 2013;1(3):72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capel SA. Psychological and organizational factors related to burnout in athletic trainers. Athl Train. 1986;21(4):322–327. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clapper D, Harris L. Determining professional burnout of certified athletic trainers employed in the Big Ten athletic conference [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl):S72–S73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gieck J, Brown RS, Shank RH. The burnout syndrome among athletic trainers. Athl Train J Natl Athl Train Assoc. 1982;17(1):36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrix AE, Acevedo EO, Hebert E. An examination of stress and burnout in certified athletic trainers at Division I-A universities. J Athl Train. 2000;35(2):139–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunt V. Dangerous dedication: burnout a risk in profession. NATA News. Nov, 2000. pp. 8–10.

- 7.Leiter MP. The dream denied: professional burnout and the constraints of human service organizations. Can Psychol. 1991;32(4):547–558. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazerolle SM, Monsma E, Dixon C, Mensch JM. An assessment of burnout in graduate assistant certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2012;47(3):320–328. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.3.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBrien AM. Burnout and Coping Among Certified Athletic Trainers in Two High School Settings [thesis] San Jose, CA: San Jose State University;; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter JM, Van Lunen BL, Walker SE, Ismaeli ZC, Onate JA. An assessment of burnout in undergraduate athletic training education program directors. J Athl Train. 2009;44(2):190–196. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilliard TM, Boulton ML. Public health workforce research in review: a 25-year retrospective. J Prev Med. 2012;42(5S1):S17–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowman TG, Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Career commitment of postprofessional athletic training program graduates. J Athl Train. 2015;50(4):426–431. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazerolle SM, Gavin KE, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Undergraduate athletic training students' influences on career decisions after graduation. J Athl Train. 2012;47(6):679–693. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.5.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.College-university value model. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. 2016 https://www.nata.org/sites/default/files/College-Value-Model.pdf Accessed June 8,

- 16.Secondary school value model. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. 2016 http://www.nata.org/sites/default/files/secondary_school_value_model.pdf Accessed June 8,

- 17.Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(3):287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsyth S, Polzer-Debruyne A. The organisational pay-offs for perceived work-life balance support. Asia Pac J Hum Res. 2007;45(1):113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Work-life balance: making it work for your business. Department of Labour Web site. 2014 http://www.dol.govt.nz/er/bestpractice/worklife/makingitwork/index.asp Accessed June 12,

- 21.Visser F, Williams L. Work-life balance: rhetoric versus reality? The Work Foundation Web site. 2014 www.theworkfoundation.com Accessed June 12.

- 22.Kahanov L, Loebsack AR, Masucci MA, Roberts J. Perspectives on parenthood and working of female athletic trainers in the secondary school and collegiate settings. J Athl Train. 2010;45(5):459–466. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The three faces of work-family conflict: the poor, the professionals, and the missing middle. Center for American Progress Web site. 2011 http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/labor/report/2010/01/25/7194/the-three-faces-of-work-family-conflict Accessed July 15,

- 25.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Athletic trainers with children: finding balance in the collegiate practice setting. Athl Ther Today. 2011;16(3):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitney WA, Mazerolle SM, Pagnotta KD. Work-family conflict among athletic trainers in the secondary school setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):185–193. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fereday J, Oster C. Managing a work-life balance: the experiences of midwives working in a group practice setting. Midwifery. 2010;26(3):311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(3):548–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hills LS. Balancing your personal and professional lives: help for busy medical practice employees. J Med Pract Manag. 2011;24(3):159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kossek EE, Lewis S, Hammer LB. Work-life initiatives and organizational change: overcoming mixed messages to move from the margin to the mainstream. Hum Relat. 2010;63(1):3–19. doi: 10.1177/0018726709352385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jyothi SV, Jyothi P. Assessing work-life balance: from emotional intelligence and role efficacy of career women. Adv Manag. 2012;5(6):35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM. Work-life balance: a perspective from the athletic trainer employed in the NCAA Division I setting. J Issues Intercoll Athl. 2013;6:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazerolle SM, Ferraro EM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Factors and strategies contributing to the work-life balance of female athletic trainers employed in the NCAA Division I setting. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2013;5(5):211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunetto Y, Farr-Wharton R, Shacklock K. Supervisor-subordinate communication relationships, role ambiguity, autonomy and affective commitment for nurses. Contemp Nurse. 2011;39(2):227–239. doi: 10.5172/conu.2011.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodman A, Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA. Achieving work-life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, part II: perspectives from head athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2015;50(1):89–94. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]