Abstract

Insane asylums began to decline around the turn of the 20th century. As patients with incurable illnesses filled them, asylums became warehouses for people who could not be maintained elsewhere. The St. Louis Insane Asylum exemplifies this trend of decline. Overcrowding and lack of funding led to placement of patients in the St. Louis Poorhouse and to unhealthy conditions at the asylum. Dr. Edward Runge, the superintendent, tried to counteract this trend of decline, but the asylum was able to offer little more than custodial care.

Trends Affecting the St. Louis Insance Asylum, ca. 1900

After a century of growth, insane asylums experienced decline in the early twentieth century. Large state institutions began as facilities where those with mental illness could come not only to receive treatment, but also to recover. By the end of the century, however, these hospitals had become custodial facilities. Public asylums housed large numbers of the mentally ill, but they were no longer providing innovative treatment, or in many cases, any treatment at all.

The St. Louis Insane Asylum is a good example of this decline among public facilities, experiencing many of the same problems that afflicted other public institutions at the turn of the century1. Patient records from 1900 show the challenges the facility faced, and how Dr. Edward Runge, the superintendent, handled those problems. Overcrowding, and use of the City Poorhouse for “overflow” patients, was a particularly vexing problem. The asylum also housed many patients with ailments that were not amenable to mental health treatment2. In addition, Dr. Runge faced financial and political challenges that made operation of the asylum difficult.

This paper will explore the origins of asylums and discuss their rise in influence in the nineteenth century. An overview of trends identified by Breakey3 as leading to the decline of the asylum will then be provided. St. Louis Insane Asylum will be discussed as an example of a facility that experienced a decline around the year 1900, using patient records and Dr. Edward C. Runge’s papers.

Origins of the Asylum

Asylums developed in the late 18th century as a place of refuge for individuals with mental illness4. The asylum was envisioned as a quiet, idyllic home where those with mental illness could be cured5. The idea of the asylum as a place to treat and cure mental illness became popular in the United States, and by the year 1860, 28 of the 33 states had public insane asylums6.

Three historical events affecting asylums in the mid-nineteenth century were the following: one, reform efforts of Dorothea Dix and others to improve treatment conditions for the insane7; two, the introduction of moral treatment into American asylums8; and three, the rise of psychiatry as a medical specialty4.

Dorothea Dix, a reformer and activist from Massachusetts, took her crusade around the United States, working to get people with mental illness out of poorhouses and jails and into asylums. Her efforts led to the founding or enlargement of over 30 mental hospitals7.

“Moral treatment” emphasized care of curable patients. Moral treatment involved establishment of a regimented daily schedule, including disciplined work6. Visits from family members were discouraged, and asylum superintendents relied on “quiet, silence, and regular routine” to restore the insane to more orderly thinking (p.138)6. Early proponents of moral treatment claimed high rates of cure.

Psychiatry came into its own in the 19th century10. Though there is some debate as to the actual level of influence that medical superintendents had in asylums9, it is clear that physicians’ classification systems and ideas regarding treatment did have an impact on state hospitals. Psychiatrists (also known as “alienists”) were optimistic that mental illness could be cured with appropriate asylum care4. There was conflict even among alienists, though; as the end of the 19th century approached, practitioners favoring rehabilitative approaches found their ideas in decline, as biological theories gained in popularity11.

“Cheerful surroundings, useful employment, entertainments, and other agencies of similar nature, have for their ultimate aim the production of healthy cerebration.”

1899 American Journal of Insanity, Dr. Edward C. Runge Superintendent of the St. Louis Insance Asylum appointed by Mayor Walbridge in 1895, and serving to 1904.

Why the Decline in Asylums?

Despite the rise of psychiatry as a specialty, publicly-funded psychiatric hospitals were in decline in the late nineteenth century3. Whereas general hospitals were becoming more modern and research-oriented in their practice12, the opposite was happening to psychiatric hospitals. Mental hospitals in the years around 1900 were the last resort before the poorhouse. Large numbers of state mental hospital inmates suffered from diseases such as senile debility and neurosyphilis, in addition to diagnoses such as depression, mania, and paranoia13. State hospitals offered little treatment, instead warehousing patients with disorders judged not only incurable but untreatable. Though the bars were coming off the windows and doors14, public asylums remained as places for those with nowhere to go. Asylums had become a “dead end” for patients and medical practitioners4.

Use of moral treatment started to decline in the second half of the 19th century as it became clear that many patients were not curable using these methods. The large state asylums assumed more of a custodial than a curative role15. In addition, the large nvms were becoming custodial facilities, with no hope for rehabilitation of their inmates.

The St. Louis Insane Asylum: Ongoing Trends

The St. Louis Insane Asylum, a city-operated hospital, had many of the problems that Breakey3 identifies as leading to the decline of public hospitals around the country. Though it was operated by a municipality rather than a state, the St. Louis Insane Asylum shared the same problems as the large state asylums elsewhere at the turn of the 20th century. Financial difficulties, overcrowding, and “dumping” of elderly persons led to difficulties in management, despite the superintendent’s efforts to maintain a curative environment.

The St. Louis Insane Asylum in 1900 was considered to have a progressive approach to care and treatment of individuals with mental illness2. Dr. Edward Runge, the superintendent, advocated holistic treatments for a variety of diagnoses, including mania, melancholia, stupor, and general paresis. In an 1899 article in the American Journal of Insanity, Dr. Runge stated that “Cheerful surroundings, useful employment, entertainments, and other agencies of similar nature, have for their ultimate aim the production of healthy cerebration”18.

Yet even this institution, with its progressive reputation, was unable to cope with the overcrowding that occurred during the late nineteenth century. With a capacity of 350 patients, the St. Louis Insane Asylum in the year 1901 housed over 660 patients19. Eventually, the asylum was able to offer little more than custodial care20.

Efforts were made to relieve overcrowding by placing patients who had no means to pay in the city poorhouse, which housed over 900 persons with mental illness in its facility, in addition to nearby outhouses and a barn19,20. By 1901, there were more persons with mental illness than “paupers” living on poorhouse grounds21. Dr. Runge was concerned about the welfare of these patients because there was no medical supervision there2.

Rates of recovery were low at the turn of the century, and Dr. Runge speculated that this was due to the high numbers of patients with dementia paralytica, senile dementia, epilepsy, and imbecility, disorders from which recovery rarely occurred. In the late 1880s, the cure rate at the Asylum was around 10 percent20.

More can be learned about the St. Louis Insane Asylum by examining patient records from the turn of the century. To understand trends affecting the patients of the St. Louis Insane Asylum, records from the year 1900 were reviewed. The microfilmed ledgers were available for examination at the Missouri Institute of Mental Health. Permission to review the records was obtained from the Missouri Department of Mental Health.

Staff at the St. Louis Insane Asylum collected a considerable amount of information on asylum inmates, including descriptions of their physical health, “symptoms of insanity,” suicidal and homicidal tendencies, “intemperate habits,” occupation, and educational level. Little information was entered into patient records about the nature of treatment, most likely because treatment in the overcrowded, underfunded asylum was probably minimal.

Dr. Edward C. Runge.

Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1856.

Died in St. Louis, February 10, 1904.

Physicians who transferred patients into the asylum from other hospitals included Dr. H. L. Nietert, a surgeon on the staff of St. Louis City Hospital, and Dr. W. H. Luedde, an ophthalmologist practicing in St. Louis.

Data were extracted from microfilmed records at the Missouri Institute of Mental Health of all patients admitted to the St. Louis Insane Asylum during 1900. Data collected on the 436 patients included sex, age, race, psychiatric diagnosis, outcome of stay, and length of stay.

Of patients admitted in 1900, 52.3% were male and 47.7% were female. Nearly all of the patients admitted (90.8%) were White, while 9.2% were classified as “Colored.” The mean age of patients was 38.1. The oldest patient was 87, and the youngest (admitted for idiocy) was six years old.

Diagnosis was divided into the following categories: melancholia, mania, addiction, dementia, diseases related to syphilis, neurasthenia, periodic insanity, diseases related to epilepsy, mental retardation, and other. Three patients were missing information on psychiatric diagnosis, so 433 patients had this information. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Psychiatric diagnosis.

| Category | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Melancholia | 61 |

| Mania | 42 |

| Addiction | 53 |

| Dementia | 89 |

| Syphilis | 62 |

| Neurasthenia | 19 |

| Periodic insanity | 12 |

| Epilepsy | 31 |

| Mental retardation | 34 |

| Other | 30 |

| Missing | 3 |

Melancholia was the term to describe depression whereas mania described a manic episode. Melancholia and mania together made up almost one-fourth of admissions (23.6%). Addictions consisted mostly of chronic and acute alcoholism, with occasional cases of chronic morphine use. Twelve percent of admissions were due to addiction.

Dementia consisted of dementia senilis (senile debility) as well as other forms of dementia, with the exception of dementia paralytica, which was counted as a disease related to syphilis. The definition of dementia is “lasting mental deterioration; especially a pathological decline in intellectual power and inappropriateness of emotional response”22. Dementia was the most common admitting diagnosis, making up 20.4% of the cases in 1900.

Diseases related to syphilis comprised lues cerebralis, general paresis, and dementia paralytica. Dementia paralytica and general paresis were the terms to describe the psychosis, dementia, and paralysis that came about because of a syphilitic infection of the brain22. Diseases related to syphilis were a common reason for admission in 1900, with over 14% of admissions due to these illnesses.

Some less common diagnoses included neurasthenia, periodic insanity, epilepsy, idiocy, and imbecility. Neurasthenia included cerebrasthenia as well as neurasthenia insanity, whose symptoms could include fatigue, insomnia, aches and pains, as well as physical and mental weakness23. Periodic insanity was related to neurasthenia, but also included the presence of “obsessional affects and obsessional ideas”23. Epilepsy included epileptic insanity, which was a group of mental illnesses characterized by the presence of seizures22. Idiocy and imbecility were terms used at that time to refer to mental retardation22. Most admissions of young children were due to idiocy or imbecility.

The outcomes of asylum stays varied widely, from complete recovery to death. The table below shows the frequency of the different outcomes. See Table 2. The most frequent outcome of a stay at the St. Louis Insane Asylum for those admitted in 1900 was death. Some deaths were due to tertiary syphilis; other patients died of pneumonia or gastrointestinal ailments. The problem of infectious disease in the year 1900 can clearly be seen in the frequent deaths of asylum patients.

Table 2.

Outcome of stay.

| Outcome of stay | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Died | 118 | 27.1 |

| Discharged recovered | 37 | 8.5 |

| Discharged improved | 81 | 18.6 |

| Discharged unimproved | 72 | 16.5 |

| Transferred to other public asylum | 9 | 2.1 |

| Transferred to St. Louis City Poorhouse | 111 | 25.5 |

| Other | 4 | .9 |

| Unknown | 4 | .9 |

| Total | 436 |

Table 3.

Length of asylum stay.

| Length of stay | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Less than one week | 13 | 3.0 |

| One week to one month | 58 | 13.3 |

| Greater than one month and less than three months | 72 | 16.5 |

| Three to six months | 49 | 11.2 |

| Six months to one year | 86 | 19.7 |

| Greater than one year and less than two years | 58 | 13.3 |

| Two to four years | 50 | 11.5 |

| Greater than four years | 47 | 10.8 |

| Unknown | 3 | .7 |

| Total | 436 |

The second most common outcome was transfer to the City Poorhouse. There was no particular correspondence between a certain length of stay or diagnosis and being transferred to the poorhouse. It did appear that many were transferred to the poorhouse after several years in the Asylum with limited improvement in mental status and waning financial support.

Little more than a quarter of inmates were discharged as recovered or improved. Many of those discharged as recovered or improved were patients with melancholia or mania. It was rare for a patient with a syphilis-related disorder to be discharged as improved.

Lengths of stay were even more varied than outcomes of stay. Some patients stayed less than a week, while others stayed ten years or more. The following table lists the frequencies of the various lengths of stay at the Asylum.

Almost 20% percent of inmates admitted in 1900 stayed between six months and one year. Over 150 of those admitted in 1900 stayed over one year—over one-third of the total admitted that year. However, another third of patients stayed six months or less.

From these patient records, there is evidence of all of the trends Breakey3 identified as affecting the operation of large public asylums. Overcrowding is evident in the asylum records. With more than a quarter of the patients being sent to the poorhouse in 1900, the asylum did not have room for all persons who needed care. Although over 100 patients were sent on to the poorhouse that year, the asylum still housed 660 patients in its facility that had capacity for 350. The asylum did not have the resources to provide treatment to all patients who might have benefited. Only 8.5% of patients admitted in 1900 were discharged as recovered from their illness.

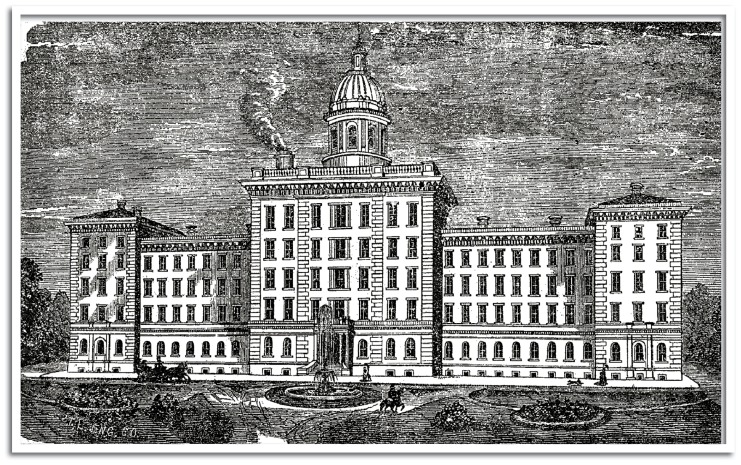

Saint Louis County Asylum 1896

Over one-fifth of patients admitted in 1900 had a diagnosis of dementia, and many of these patients had dementia senilis, or senile debility, related to old age. The large number of elderly patients admitted into the facility may have prevented the asylum from providing the intensity of services that would have been helpful for patients with diagnoses such as melancholia, mania, or paranoia.

Furthermore, it is clear from the records of the St. Louis Insane Asylum superintendent, Dr. Edward Runge, that the asylum was plagued with financial difficulties. In 1898, when the St. Louis City Health Commissioner recommended that the St. Louis Insane Asylum be placed under state control, Dr. Runge wrote an emphatic letter to the commissioner, exhorting him to keep the asylum under city control. Dr. Runge believed that transferring the asylum to the state would cost the city even more money because if the asylum were transferred to state control, the city would have to pay the state to house its own patients with mental illness in the facility. Dr. Runge believed that this cost would amount to more money than the city was currently paying to care for the insane. He told the commissioner of the problems with severe overcrowding at the St. Louis facility and informed the commissioner of his policy of sending people with chronic illnesses to the poorhouse24.

Runge was tireless in his advocacy for the St. Louis Insane Asylum, but he did not always obtain funds he sought from the city health commissioner or the mayor. The asylum was short on resources, and many patients were transferred to the poorhouse, where they received no medical treatment20. Runge further felt that Democratic party corruption prevented him from effectively managing the asylum, because the party bosses had the power to appoint Runge’s staff and used that power to place unqualified individuals into asylum staff positions25.

Conclusion

The St. Louis Insane Asylum in 1900 shared many of the problems that other public institutions for the mentally ill had at that time. Despite the efforts of its superintendent, this facility faced financial troubles and overcrowding. Many of the asylum’s patients ended up at the St. Louis City Poorhouse, with no medical supervision. Asylums across the country at this time were becoming more custodial in nature, as psychiatrists shifted their practice to outpatient and short-stay facilities. Dr. Runge remained devoted to the St. Louis Insane Asylum until his departure in 1904, but he could not prevent its decline. More than a quarter of the patients admitted to the asylum in 1900 died while in the facility, and only a few were discharged as recovered. The primarily working-class constituency of the asylum could not provide funds sufficient to keep up the facility and prevent overcrowding.

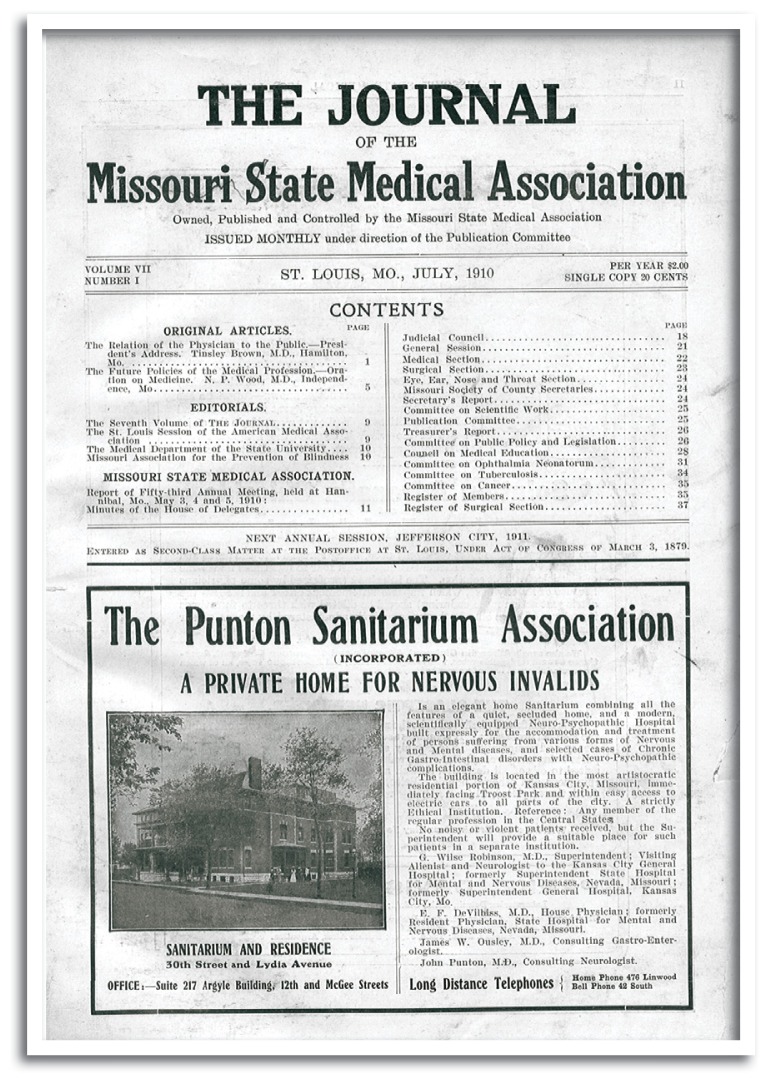

Missouri Medicine Cover, November 1910.

The seventh volume of Missouri Medicine had a redesigned cover displaying its very first advertisement for the Punton Sanitarium Association in Kansas City.

The trend affecting public mental hospitals was the opposite of what was occurring with other large hospitals. Whereas facilities treating medical disorders were becoming more sophisticated and increasingly attractive to middle-class patients, public asylums were in decline. Though the population of large public asylums continued to increase into the 1950s, these facilities were thought of as the last resort for individuals with chronic mental illness. The St. Louis Insane Asylum provides an example of the “dead end” that Shorter chronicles in the history of psychiatry4. Patients there had few places to go except the poorhouse, which was an unwelcome alternative to asylum care.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Dr. Joseph Parks, Missouri Department of Mental Health, and to Christina Sullivan, Mary Johnson and the staff of the Missouri Institute of Mental Health Library. Photos courtesy of the Missouri Institute of Mental Health.

Biography

Melissa A. Hensley, PhD, is an Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Augsburg College in Minneapolis. She is a successful doctoral candidate from the George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis.

Contact: hensleym@augsburg.edu

References

- 1.Grob GN. Mental Illness and American Society, 1875–1940. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Runge EC. Review of eight years’ work at the St Louis Insane Asylum. Interstate Medical Journal. 1903;10(10):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breakey WR. The rise and fall of the state hospital. In: Breakey WR, editor. Integrated Mental Health Services: Modern Community Psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shorter E. A History of Psychiatry: From The Era of the Asylum To The Age of Prozac. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenblatt A. Concepts of the asylum in the care of the mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1984;35(3):244–250. doi: 10.1176/ps.35.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothman DJ. The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 2002. Rev ed. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grob GN. The Mad Among Us: A History of the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dain N. The chronic mental patient in 19th-century America. Psychiatric Annals. 1980;10(9):323–327. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright D. Getting out of the asylum: Understanding the confinement of the insane in the nineteenth century. Social History of Medicine. 1997;10(1):137–155. doi: 10.1093/shm/10.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grob GN. The transformation of the mental hospital in the United States. The American Behavioral Scientist. 1985;28(5):639–654. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb HR. A century and a half of psychiatric rehabilitation in the United States. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(10):1015–1020. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.10.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens R. Sickness and In Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starks SL, Braslow JT. The making of contemporary American psychiatry, Part I: Patients, treatments, and therapeutic rationales before and after World War II. History of Psychology. 2005;8(2):176–193. doi: 10.1037/1093-4510.8.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins-Evenson RR. The Price of Progress: Public Services, Taxation, and the American Corporate State, 1877 to 1929. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothman DJ. Conscience and Convenience: The Asylum and Its Alternatives in Progressive America. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 2002. Rev ed. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz MB. Poorhouses and the origins of the public old age home. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, Health and Society. 1984;62(1):110–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner D. The Poorhouse: America’s Forgotten Institution. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Runge EC. Our work and its limitations. American Journal of Insanity. 1899;56(1):53–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Mayor’s Message with Accompanying Documents to the Municipal Assembly of the City of St. Louis for the Fiscal Year Ending April 7, 1902. St Louis MO: The St. Louis Chronicle; 1903. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crighton JC. The History of Health Services in Missouri. Omaha, NE: Barnhart Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Mayor’s Message with Accompanying Documents to the Municipal Assembly of the City of St. Louis for the Fiscal Year Ending April 8, 1901. St Louis MO: Nixon-Jones Printing Company; 1901. [Google Scholar]

- 22.English HB, English AC. A Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychological and Psychoanalytic Terms: A Guide to Usage. New York, NY: Longmans Green, and Co; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinsie LE, Campbell RJ. Psychiatric Dictionary. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Runge EC. Letter to Max C. Starkloff, City Health Commissioner. Edward C. Runge Papers. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Historical Society; 1898. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newspaper clipping from Edward C. Runge Papers. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Historical Society; 1904. Menace of the Pull. [Google Scholar]