Abstract

The focus of this review is on “hepatitis”; diagnostic considerations of common adult medical liver diseases are presented, including chronic hepatitis C and B, autoimmune hepatitis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, drug-induced liver injury, and chronic cholestatic liver diseases. Processing, protocol stains, and final reporting of findings are discussed

Introduction

Liver biopsy is the result of a clinical decision that balances the possibility of morbidity and mortality related to the procedure (ranging from 0.009–0.11%) with the potential diagnostic and/or prognostic information to be gained. The indications for biopsy for medical liver disease in adults occur in broad, somewhat overlapping categories, as shown in Table 1. Occasionally liver biopsies are performed for the clinical concern of alcoholic liver disease (ALD), but often patients with ALD are managed without biopsy. Clinically recognized hereditary hemochromatosis is arguably an indication for biopsy in patients over 40 years to evaluate for fibrosis, 1 but is no longer required for diagnosis or iron quantitation. It has been argued that neither primary biliary cirrhosis nor primary sclerosing cholangitis require biopsy for diagnosis, 2, 3 but not all clinicians concur; disease processes supportive of chronic cholestatic disease may also be encountered in biopsy evaluation. Liver biopsy is very rarely undertaken in settings of acute hepatitis as clinical testing can provide diagnostic information. Thus, the processes most often encountered by surgical pathologists in the non-transplant setting are the biopsy for “chronic” hepatitis or elevation of liver tests of unknown or unidentified etiology

Table 1.

The most common clinical indications for adult medical liver biopsy.

|

|

|---|---|

|

Rejection, acute or chronic |

| Recurrence of disease De novo hepatitis |

|

| Inflow or outflow vascular lesions | |

| Biliary obstructive changes | |

|

|

| Cholestatic tests (alk phos) | Space-Occupying lesions |

| Sarcoidosis | |

Sinsoidal infiltrates:

|

|

| Large vein outflow obstruction | |

| Mixed cholestatic and hepatitic tests | Drug-induced cholestatic hepatitis |

| Hepatitic | A1AT, Wilson disease, Drug-induced liver injury, steatosis, steatohepatitis |

|

|

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | |

| Suspected drug-induced hepatitis | |

|

|

| Chronic hepatitis C with or without HIV | |

| Treated autoimmune hepatitis: improved or not | |

| GVHD: zone 3 and outflow vein necrosis or hepatitic form | |

| Alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis |

The broad categories of indications are in the left column and potential diagnostic considerations in the right column.

Neither list is exhaustive.

It is incumbent upon pathologists to respect the decision process to biopsy, and to provide the best information possible from a tissue fragment that represents no more than 1/50,000 of the adult organ. The first step in the evaluation of a liver biopsy is appropriate management of tissue processing. As the biopsy is small, it should be submitted intact, without any sectioning. The use of an embedding sponge is highly likely to result in artefacts that commonly create triangular indentations of the tissue and can impair interpretation; therefore, for liver biopsies, the use of sponges is discouraged.4, 5. There is no need to “ink” liver biopsies, unless the histology technicians request the use of eosin to ease embedding. Blue and black ink predictably impair interpretation. With careful sectioning at the time of the preparation of the limited histologic slides, the need to return to the block is unlikely

Implementation of standard protocols is recommended. A common protocol results in 1–3 “slices” per slide as follows: 3 slides for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E); 1 slide each for collagen staining (Masson’s trichrome or Sirius red), reticulin staining, PAS with diastase (PASd), modified Perls’ (iron); and 4–6 unstained slides. To be most informative, “special stains” should be performed on the slides that alternate with the H&E stained sections. With unstained slides available, further stains such as rhodanine (for copper), AFB and GMS for granulomas and in all HIV cases, orcein (for elastic fibers; which are absent in recent collapse, but present in evolving and mature fibrosis), or immunohistochemistry (for HBV, CMV, HSV, etc) can reliably be performed in a timely fashion

Initial Evaluation

Adequacy determination is a significant component in medical, non-tumor liver biopsy evaluation. The most common method is to estimate the number of complete portal tracts in the specimen. With proper biopsy techniques, whether by aspiration or use of cutting needles, suction or biopsy “gun”, and whether percutaneous or transjugular, current standards are for ≥ 6 complete portal tracts for evaluation, but ≥ 11 portal tracts are recommended for confidence in grading and staging.6 Recognized advantages of transjugular liver biopsies include (1) ability to biopsy patients with coagulation disorders; (2) ability to measure hepatic vein pressures and gradients; (3) ability to perform multiple passes into the liver. The disadvantages of transjugular biopsies, shared by percutaneous biopsy, are related to the technical expertise in obtaining the specimen, and the gauge of the needle utilized. Published literature and personal experience support the use of at least an 18 gauge needle with preference for larger sizes.6 The “gun” biopsy has been shown to be a useful procedure for obtaining intact cores from cirrhotics. As with any other medical tissue biopsy, it is preferable for pathologists to report inadequacy of biopsy material when appropriate rather than imply confidence in the diagnostic evaluation. Adequacy of biopsy may be challenging in fragmented specimens; reticulin and trichrome stains will guide the final diagnostic determination of cirrhotic fragmentation versus technical fragmentation. In cirrhosis, the tissue fragments are rounded and either completely or partially surrounded by either dense or delicate connective tissue septa, and the intervening hepatic nodules show double plates, consistent with regenerative nodules

Low power evaluation for overall pattern involves observations of architecture, injury pattern, and inflammation; several issues must be addressed. First, is the parenchyma architecturally intact, i.e., are portal tracts and outflow veins present and evenly spaced? If not, are the vascular relationships disordered due to loss of parenchyma (bridging necrosis, collapse), fibrosis, cirrhotic remodelling or nodularity without fibrosis? Second, is the process steatotic, hepatitic or cholestatic (Table 2)? Do the plates appear uniform, is there cord disruption and disarray, are hepatitic or cholestatic rosettes noted, are the cords thickened (> 1 nucleus in width)? Third, if inflammation is present, is it predominantly portal, lobular, sinusoidal or a combination? What cell types comprise the inflammatory infiltrates? Are granulomas present; if so, what is the nature of the granulomas?

Table 2.

Hepatitic versus Cholestatic Liver Parenchymal Alterations

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

A, C | A,C |

|

C | +/− in C |

|

Possible in alcoholic hepatitis | A, C |

|

A,C | +/− A,C |

|

A much greater than | C Rare |

|

Hepatitic: A,C | Cholestatic: +/− A,C |

|

|

+/− A; +/− C | Rare; would suggest “overlap” |

|

No | A much greater than |

|

Rarely in cirrhosis (C) | C |

|

No | Rare in A; + in C |

|

||

| Portal-based | Only C | Only C |

| Zone 3 perisinusoidal | Only C (NASH or ASH) | No |

| THV remains in central location in bridging fibrosis | Rare | Common in C |

A= acute

C=chronic

The timing of incorporation of clinical data into the diagnostic algorithm of liver biopsy interpretation is a personal choice; at some point, however, clinical information must be known. For some diseases, such as chronic hepatitis, clinical information must be incorporated into the final diagnostic pathology report. The first descriptor in the diagnostic line is the histopathologic finding(s) of “chronic hepatitis” followed by the clinical diagnosis, such as HCV, HBV, AIH, etc. This information is followed by semi-quantitative evaluation of activity (grade) and presence/amount of fibrosis (stage). Whether these latter two are given numerically, verbally, or both is another personal choice, but the exact method of evaluation should be understood by the clinicians receiving the report

It is well established that histologic changes may or may not be in accord with clinical presentation. As examples, patients may present with “acute onset” of liver test elevations, but on biopsy there are features of chronicity such as cirrhotic septa, a finding that can be a useful clue to possible etiology, and can occur in autoimmune hepatitis. Alcoholic hepatitis, an active hepatitis with dense perisinusoidal fibrosis, may present clinically as cirrhosis or as febrile illness. Biopsies in chronic cholestatic liver disease (PBC, PSC) do not show features of bile stasis (acute cholestasis) until hepatic decompensation occurs. Venous outflow obstruction of both recent or remote onset may present with a cholestatic pattern of clinical laboratory abnormalities (i.e. elevated alkaline phosphatase)

Chronic Hepatitis: HCV, HBV, AIH

“Chronic hepatitis” is characterized by chronic inflammation that is predominantly in the portal tracts, with evidence of interface activity (what used to be referred to as “piecemeal necrosis”). In this process, chronic inflammatory cells breach the collagenous limiting plate, and percolate through and surround adjacent hepatocytes. A clue that this process has occurred is the presence of hepatocytes within the fibrous matrix of the portal tract. Thus, “trapped” hepatocytes are evidence of prior interface activity and the biopsy is designated as periportal fibrosis. Fibrosis of any amount may or may not be present in chronic hepatitis; thus, fibrosis is not a “required” feature for diagnosis

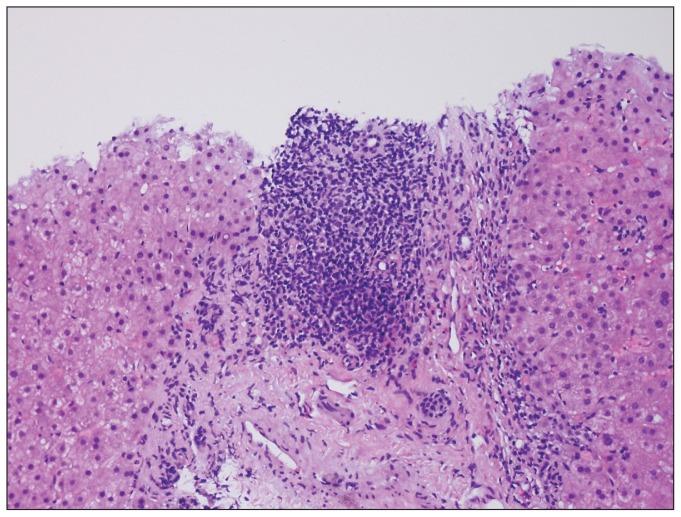

Chronic hepatitis C is characterized by lymphoid aggregates, sometimes even lymphoid follicles with germinal centers, and mild-moderate foci of interface activity (Figure 1). The lobular activity is mild and consists of spotty necrosis with 1–2 mononuclear cells and occasional acidophil (apoptotic) bodies. In genotype 3, macrovesicular steatosis is present, typically in 30–66% of the biopsy. In non-genotype 3, macrovesicular steatosis may be present in varying amounts and in various zonal distributions, and may represent underlying predisposing conditions (overweight, diabetes, alcohol use). The interplay of steatosis and viral hepatitis C is complex and under investigation.7

Figure 1.

Portal lymphoid aggregates while not diagnostic of chronic hepatitis C, are quite characteristic. Interface activity can be seen along the edges of the limiting plate

Other findings of hepatitis C include the “Poulsen lesion” in which the bile duct is infiltrated by lymphocytes; presence of eosinophils in the portal infiltrates; and in some cases, the presence of portal venous endotheliitis. As all of these findings can be seen in allograft rejection, it is often challenging to differentiate lesions of acute cellular rejection vs recurrent hepatitis C in allograft biopsies

The progression of fibrosis in hepatitis C originates from portal tracts: portal expansion, periportal fibrosis (with or without rare bridging septa), bridging fibrosis with parenchymal nodularity, and cirrhosis. If perisinusoidal fibrosis is also present, a consideration of prior zone 3 injury (alcohol, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or cardiac) is given

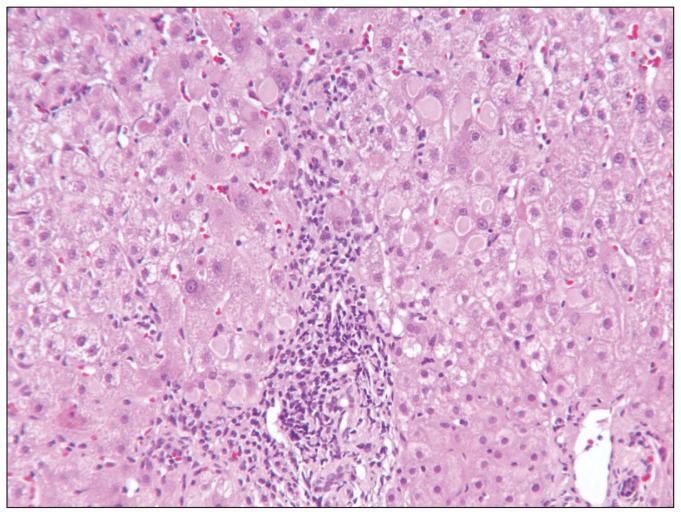

Chronic hepatitis B may or may not have features of increased lobular activity in addition to the features of chronic hepatitis described above. This activity may be quite severe (with confluent or bridging necrosis) in “reactivation” or in flares during seroconversion. The presence of intracytoplasmic ground glass inclusions, however, is an indication of chronicity (Figure 2). HB S Ag and HB C Ag, which can be visualized with immunohistochemistry stains, are not found in acute HBV infection. Patterns of immunostaining for HBS Ag include membranous, of intracellular inclusions, or diffuse cytoplasmic reactivity. The affected cells are nonzonal and in clusters. Core Ag is positive in nuclei, but may also be present in the cytoplasm. A commonly confusing process of active HBV is the presence of plasma cells. The progression of fibrosis in HBV is similar to that of HCV, however, since HBV may have episodically marked activity, there may be larger areas of “parenchymal extinction” and fibrosis

Figure 2.

Ground glass inclusions in chronic hepatitis are an indication of HB S Ag, but should be confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Interface activity can be noted as well

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) can be quite variable in both clinical and histologic presentation. A “classic” case has marked portal and lobular chronic inflammatory infiltrates, a predominance of plasma cells at the interface and in lobular foci of spotty necrosis, hepatitic rosettes, and focal confluent (perivenular) or bridging necrosis. Eosinophils may be present in the portal inflammation. Plasma cells in clusters are noted in the foci of necrosis

Variants of otherwise clinically uncomplicated AIH include (1) cases with only mild portal and lobular activity, (2) cases with only “acute hepatitis” with confluent necrosis in zone 3 8 or zone 3 canalicular cholestasis, (3) cases without the plasma cell predominance, and (4) cases of unexpected cirrhosis with or without ongoing necroinflammatory activity. Fibrosis in AIH may resemble that of other forms of chronic hepatitis (portal-based), but may also have large areas of parenchymal extinction with fibrosis. The final diagnosis of AIH rests with several clinical findings; including elevation of plasma proteins and in particular, gamma globulins, with a predominance of IgG;. ANA seropositvity, although it may also be negative and is unspecific since it may occur in many other forms of chronic liver disease; seropositivity for ASMA is commonly present

“Overlap” hepatitis is a clinical and pathologic term that can be used in a variety of situations; for pathologists, the most common settings are overlap of AIH with HCV, PBC, steatohepatitis, or PSC. Overlap features may be clinically unsuspected, thus it is important to adequately identify and explain the features which prompted the histologic diagnosis of “overlap”. ANA seropositivity in chronic liver disease is not evidence of overlap, and overlap is NOT merely the presence of plasma cells in portal chronic inflammatory infiltrates. AIH overlap includes marked plasmacellular infiltrates in the interface activity and in lobular activity, and other histologic features that support AIH. Which disease features (AIH or other) are predominant in the biopsy are of the most interest since they determine the choice of treatment

Differential Diagnostic Considerations in Chronic Hepatitis

Clues to differential diagnostic considerations include the type(s) of portal inflammation. Lymphoid aggregates or follicles are common but not exclusive to HCV since they can occur in HBV and in AIH. A predominance of plasma cells, particularly at the interface, is a common but not required finding in AIH. Hepatitic rosetting is a manifestation of severity; the differential diagnosis includes, but is not limited to AIH; severe drug or viral hepatitis may also result in rosetting. Interestingly, acute HCV may share many features of AIH: portal plasma cells with “interface activity” or even zone 1 necrosis, lobular microgranulomas, and marked lobular disarray. Eosinophils in the portal infiltrates may represent HCV, AIH, or drug-induced liver injury (DILI). The presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes surrounding individual hepatocytes (known as satellitosis) and admixed with a ductular reaction (proliferating ductules) in a periportal area with a stellate shape are indicative of alcoholic hepatitis

As noted, necroinflammatory activity in the lobules varies in hepatitis and may provide diagnostic clues. Easily observed acidophil bodies are most commonly noted in HCV and DILI. Lobular inflammatory infiltrates can be predominantly within sinusoids, or more scattered in the lobules. The presence of “Indian file” formation of mononuclear cells within the sinusoids suggests hepatitis C, liver involvement by “mononucleosis” (due to either EBV or non-EBV causes), or phenytoin toxicity. Plasma cell clusters in foci of confluent or bridging necrosis are strongly suggestive of AIH, but may be seen in DILI. Easily observed eosinophils and/or epithelioid granulomas in the lobules are suggestive of DILI. Numerous large and sometimes confluent granulomas with concentric fibrosis raise concern for sarcoidosis

Grading and Staging Chronic Hepatitis

There are several grading and staging systems for all forms of chronic hepatitis. 9 Grade is the result of lobular activity, portal inflammation, and interface activity, i.e., potentially reversible lesions. Stage is based on the extent of fibrosis as well as architectural alterations in the parenchyma, i.e., likely irreversible lesions. It is important that the pathologists and clinicians are familiar with the subtle implications of differences between the various staging systems in use Knodell, Scheuer, Batts and Ludwig, Ishak, METAVIR, etc) so that the assigned numeric value is not misconstrued. 9, 10 In some settings, it is best to simply give descriptive morphologic descriptions of “activity” and fibrosis, (e.g., mild, moderate, marked) rather than a numeric value.11

Other Lesions of Clinical “Chronic Hepatitis”

Steatosis and steatohepatitis

Currently, both obesity and alcohol over-use are common and may result in increased lipid storage in hepatocytes. Steatosis is typically in the form of macrovesicular droplets within hepatocytes, in which either a single large droplet replaces the cytoplasm and causes eccentric displacement of the nucleus, or in which mixture of small and large droplets are present in the cytoplasm. True microvesicular steatosis is uncommon, as it presents with fulminant liver failure. Whether steatosis is derived from obesity, diabetes, or alcohol consumption; viral infection (specifically HCV, gt 3); or medications (e.g. steroids) cannot be discerned by the pathologist. However, any amount of steatosis is worth note, as it may play a role in progression of liver disease or response to anti-viral therapy. 7

There are well-defined criteria for diagnosing steatohepatitis, both with and without concurrent liver disease.12 13 In addition to steatosis, inflammatory foci and damage to hepatocytes in the form of ballooning are present. In noncirrhotic livers, the steatosis and liver cell injury are concentrated in zone 3 (perivenular region). Steatosis is graded according to the percent of each acinus filled (or surface area of the biopsy filled); this is reported as none (0–5%), 5–33%, 33–66%, and >66%. Ballooned hepatocytes are usually enlarged, but always have cytoplasmic alterations and may contain a Mallory-Denk body (Mallory’s hyaline). The characteristic alteration is one that gives the cell a flocculent appearance. Ballooned hepatocytes may or may not contain small steatotic droplets. K8/18 absence by immunostainingis characteristic of ballooning. Lobular inflammation is usually in the form of scattered foci of spotty necrosis, microgranulomas, or single-vacuole lipogranulomas. However, in some cases, the lobular inflammation in zone 3 may be so intense as to cause confusion with acinar localization; the presence of an artery branch near the outflow vein in these cases may add to the confusion. 14 Portal inflammation may be absent, mild, or marked; when marked, query for other possible causes is indicated.15 In steatohepatitis, fibrosis begins in zone 3 in the perisinusoidal spaces, in contrast with the portal-based fibrosis of chronic hepatitis, and thus forms the basis of evaluation for stage.16 With progression, portal or periportal fibrosis may occur; areas of bridging and cirrhosis may or may not retain foci of perisinusoidal fibrosis

The diagnosis of steatohepatitis concurrent with other liver diseases is also made based on defined criteria; because steatosis, hepatocyte swelling, and inflammation may occur in other chronic liver diseases, the criteria differ somewhat. 17 Thus, the necessary diagnostic feature of concurrence is the characteristic zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis, as this is not a feature of uncomplicated chronic hepatitis due to viral causes, autoimmunity, Wilson disease, or A1AT-related hepatitis

A1AT globules may or may not require a PASd stain to visualize them in their characteristic periportal hepatocellular location. If seen, formal genotyping is recommended regardless of the serum A1ATlevel, as A1AT is an acute phase reactant

Wilson Disease is the archetypical protean liver disease clinically and histologically. Unexplained steatosis or steatohepatitis, or chronic “hepatitis”, particularly in a young adult, should raise the concern. Copper quantitation from the tissue block (not a copper stain) is the only true method of diagnosis

Cholestatic liver diseases may share varying degrees of hepatitic features (both in portal and lobular regions), however, the features noted in Table 2 specific to cholate stasis are not observed in chronic hepatitis

Vascular diseases remain in the differential for clinical “chronic hepatitis”. These diseases, however, are characterized by pauci-inflammatory processes that alter zone 3, initially characterized by sinusoidal dilatation and varying amounts of cord atrophy, fibrosis, and/or red cell extravasates

Biography

Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD, MSMA member since 2010, is a Professor, Pathology and Immunology, Section Head, Liver and GI Pathology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Contact: ebrunt@path.wustl.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported

References

- 1.Bacon BR. Hemochromatosis: Diagnosis and management. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(3 Special Issue SI):718–25. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:291–308. doi: 10.1002/hep.22906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silveira MG, Lindor KD. Clinical features and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14:3338–49. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landas SK, Bromley CM. Sponge arteifact in biopsy specimens. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 1990;114:1285–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kepes JJ, Oswald O. Tissue artefacts caused by sponge in embedding cassettes. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1991;15:810–2. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalambokis G, Manousou P, Vibhakorn S, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy-Indications, adequacy, quality of specimens, and complications-A systematic review. Journal of Hepatology. 2007;47:284–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paradis V, Bedossa P. Definition and natural history of metabolic steatosis: histology and cellular aspects. Diabetes and Metabolism. 2008;34:638–42. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(08)74598-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pratt DS, Fawaz KA, Rabson A, et al. A novel histological lesion in glucocorticoid-responsive chronic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:664. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunt EM. Grading and staging the histopathologcial lesions of chronic hepatitis: The Knodell histology activity index and beyond. Hepatology. 2000;31:241–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunt EM. Liver biopsy interpretation for the gastroenterologist. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2000;2(1):27–32. doi: 10.1007/s11894-000-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishak KG. Chronic hepatitis: morphology and nomenclature. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:690–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: pathologic features and differential diagnosis. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 2005;22:330–8. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. In: Burt AD, Portmann BG, Ferrell LD, editors. MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver. 5th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2007. pp. 367–98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrell L, Belt P, Bass N. Arterialization of central zones in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2007;46:732A. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunt EM, Clouston AD. Histologic features of fatty liver disease. In: Bataller R, Caballeria J, editors. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Barcelona: Permanyer; 2007. pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94(9):2467–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunt EM, Ramrakhiani S, Cordes BG, et al. Concurrence of histologic features of steatohepatitis with other forms of chronic liver disease. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:49–56. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000042420.21088.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]