Abstract

The 1999 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report estimated that as many as 98,000 medical error related deaths occur each year in the United States; and although some argued the accuracy of the number, few denied the gravity. Medical error produces more fatalities than motor vehicle accidents, or other more publicized nonmedical disasters, and is one of the leading causes of death.

Introduction

One-half to two-thirds of hospital adverse events may be attributable to surgical care.1–4 A 2008 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has an opening banner stating “Surgical errors cost nearly $1.5 billion annually.”5 This report brings home the message that surgical errors are expensive, but seems to get carried away when it describes costs “for surgery patients who experienced acute respiratory failure or postoperative infections, respectively, compared to patients who did not experience either error.” One can certainly take issue with the implication that every post-operative acute respiratory or wound infection represents an error; there may be room to question the accuracy of the numbers and the data seems presented in a manner designed to grab attention in a world of one minute sound bites. Consequently, it’s easy to become distracted by the argument about how data is derived and presented; but really improving surgical care is what we’re interested in. Recognizing, reporting, and learning about error is more useful than the debate, and decreasing surgical error is the most valuable.

“Surgery has been made safe for the patient; we must now make the patient safe for surgery with the proper preoperative care and proceedings of anesthesia.” These are the words which Palumbo borrowed from the Georgia Hospital Association for number six of “The Ten Commandments of a Surgeon” in his 1959 “Surgical Service Guide.”6 Anesthesia wasn’t nearly as safe in the 1950s as now. Becher7 reported in 1954 that anesthesia was the primary cause of mortality in 3.7 deaths per 10,000 anesthetics. This report was neither welcomed nor embraced by the anesthesiologists of the day. However, additional studies documented rates ranging from one to twelve deaths per 10,000 anesthetics.8 The anesthesia community deemed that unacceptable. Study commissions proliferated, closed claims analyses were done and an unceasing incremental journey to improve anesthetic patient safety was under way. Today, the anesthetic mortality rate is 0.08 deaths per 10,000 anesthetics9, a ~ 50 fold improvement that is an industry benchmark for improvement and worthy of emulation.

Never Events

In 2002, The National Quality For um prepared a list of 28 serious reportable events, later expanded to 29.10 These were considered to be so egregious that they should never occur in a quality health care system, and have come to be called “never events.”

Five of them are surgical:

Surgery performed on the wrong body part.

Surgery performed on the wrong patient.

Wrong surgical procedure performed on a patient.

Unintended retention of a foreign object in a patient after surgery or other procedure.

Intraoperative or immediate postoperative death in an ASA Class I patient.

Hospitals have been fined for unintended retention of foreign bodies11 and the implication is that if quality health care standards were followed, these events will never occur.

Wrong site/wrong patient/wrong procedure events are not rare. Most, but not all, reports arise from the operating room. Seiden and Barach12 reported in the Archives of Surgery that there are an estimated 1,300 to 2,700 of these events per year in the United States. Wrong site surgeries are the most common sentinel events reported to the Joint Commission. It is estimated that one in five orthopedic hand surgeons will perform a wrong site surgery in their lifetime13; twenty-five percent of a surveyed group of neurosurgeons admitted to having made an incision on the wrong side of the head and 35% of all neurosurgeons in practice for more than five years disclosed a wrong level lumbar spine procedure.14

Unintended retention of a foreign body (RFB) is thought to be underreported. Frequencies reported range from as little as one in 18,760 inpatient operations,15 to one in 5,50016; the physical, emotional and financial costs are large.

The “Universal Protocol” became a Joint Commission mandatory standard in 2004. It includes a pre-procedure verification process, surgical site marking and a “time out” immediately before the procedure starts. All good and reasonable ideas, but they have not decreased surgical “never events” to an acceptable level. Errors in site marking (including marking the wrong site) continue to occur and passive participation in the “time out” process is not unusual. Counts of foreign bodies (sponges, instruments, needles, etc.) are routinely done and help to prevent unintended retention. As many as 88% of RFB are associated with a correct count15,16 and as little as 1.6% of discrepant counts are actually associated with an RFB.17

Human Error

Total success of the “Universal Protocol” and surgical counting procedures will require flawless performance 100% of the time - an unobtainable goal. Health care workers are talented and dedicated, but human error is at some level inevitable.

In the seminal article “Human Error: Models and Management”18 Reason notes that “Blaming individuals is emotionally more satisfying than targeting institutions.” Consequently, the person approach to dealing with error focuses on reducing unwanted variability in human behavior. The methods used include policies and procedures, poster campaigns, education, disciplinary measures and ‘blame and shame’. The “person” approach yields limited success and has unintended consequences. It thwarts a reporting/learning culture, it overlooks the fact that it is often the best people who make the worst mistakes and it ignores the finding that mishaps tend to fall into recurrent patterns. The “systems” approach, on the other hand, focuses on building defenses, safeguards and barriers to prevent accidents in an environment that includes humans. Reason notes that, “we cannot change the human condition, but we can change the conditions under which humans work.”

A Tool From Atul

In his most recent book “The Checklist Manifesto,” 19 general surgeon-popular author Atul Gawande, MD, writes about “The End of the Master Builder.” He notes that for centuries the way people put up buildings was to go out and hire a Master Builder who designed them, engineered them and oversaw construction at every step of the way. As he visited with Joe Salvia, the structural engineer for his hospital’s new wing, he learned that by the middle of the twentieth century the Master Builder was dead and gone. The complexities of major modern construction had overwhelmed the abilities of any individual to master them. The divisions of labor, engineering, air circulation, plumbing, and so forth, had become split off into specialties and subspecialties with their own areas of knowledge and expertise. Like medicine, it became more complex with more superspecialists. In medicine, however, we cling to the idea of the Master Builder - “a lone Master Physician with a prescription pad, an operating room and a few people to follow his lead, plans and executes the entirety of care - from diagnosis through treatment.” Duplicated, flawed and uncoordinated care is sometimes the result. Salvia showed him how his industry developed communication systems and checklists that have helped produce an astonishing record of success with an avoidable building failure rate of only 0.0002 per cent.

Lack of a team atmosphere and ineffective communication have been identified as the common causes of wrong site/wrong patient/wrong surgery.12, 20 Brian Sexton, PhD, a Johns Hopkins psychologist, learned that half the time the staff in an operating room after a case didn’t know each other’s names. In the half that did know each other the level of communication in the case was much better. Operating room briefings designed to increase communication and develop team behavior have been shown to improve perceptions of collaboration21 and decrease death and major complication.22 Interestingly, physician perception of teamwork is higher than that of other caregivers in the operating room.23

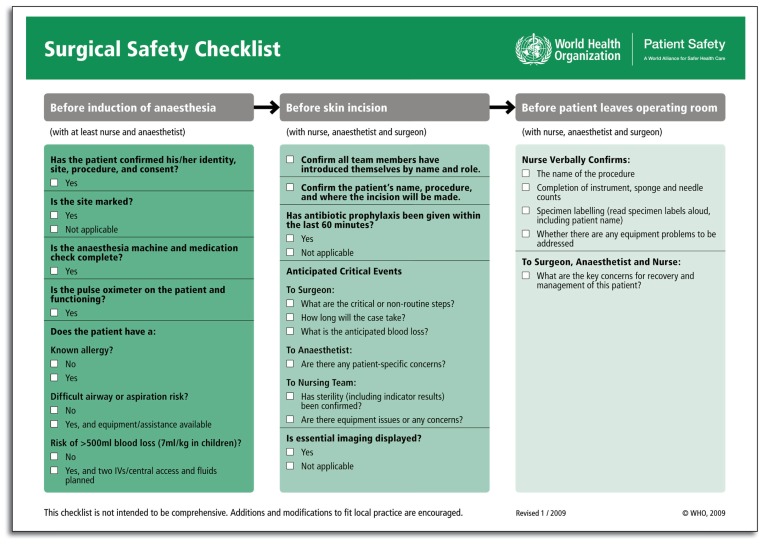

A nineteen-item surgical safety checklist, designed to improve team communication and consistency of care, has proven to reduce complications and deaths associated with surgery.24 This study, done in eight hospitals representing a wide range of economic circumstances, showed that use of the checklist in surgery was associated with a 36% reduction in major complications and a 46% decrease in death; plus, infections decreased by almost half and the number of patients having to return to the operating room for bleeding or other technical problems fell by one-fourth. Surgical checklists are promoted in the United Kingdom with the belief that they can help to open up the lines of communication among members of the operating room team and aid in improving safety and clinical outcomes. Regarding the National Health System’s checklist, Jan Rayner, senior Operating Department Practitioner at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust, states with British phraseology that, “Surgical teams that have signed up to the changes recommended are less rushed, better prepared and simply more professional.” Mark Emerton, MD, consultant orthopedic surgeon at the same institution says, “The time invested in conducting briefings and using the checklist is more than compensated by the overall efficiency achieved for the operating list. Working this way I have increased my list from four to five joints.” 25

Summary

Although one may chose to debate the validity of numbers presented, medical and surgical error is not rare, and any clinician with a patient who’s suffered from error, knows of one too many. Until recently our profession has been hesitant to talk about errors; they’ve been underreported and we haven’t learned all that we could from them. Clinicians and non-clinicians have an increasing awareness of the depth and breadth of surgical error, and there is a call for reduction. Anesthesiology has made great strides in decreasing error (and improving outcomes) and gives us assurance that it can be done.

Many surgical errors arise out of communication problems and team work deficiencies. The WHO Surgical Checklist (See Figure 1) developed by Gawande and others, seems rather simple, but, it has been proven to make the peri-surgical care safer.

So, if I gave you a deceptively simple-looking checklist, “A tool from Atul,” that has been shown to decrease major complications by 36% and mortality by 46%, would you use it?

Biography

Gerald Early, MD, FACS, MSMA member since 1982, is Associate Professor of Surgery at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Contact: earlyg@umkc.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.Kohn Linda T, Corrigan Janet M, Donaldson Molla S., editors. Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Eng J Med. 1991;324:377–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawande AA, Thomas EJ, Zimmer MJ, et al. The incidence and nature of surgical adverse events in Colorado and Utah in 1992. Surgery. 1999;126:66–75. doi: 10.1067/msy.1999.98664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gawande AA, Zinner MJ, Studdert DM, et al. Analysis of error reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals. Surgery. 2003;133:614–621. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Research Activities. Vol. 337. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palumbo LT. Surgical Service Guide. Chicago: The Year Book Publishers; 1959. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beecher HK, Todd DP. A study of the deaths associated with anesthesia and surgery. Ann Surg. 1954;140:2–34. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195407000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierce EC. The 34th Rovenstine Lecture. [Accessed 11/30/2009]. http://www.aspf.org/utils/printapage.aspx?title=Anesthesia%20Patient%20Safety%20Foundation.

- 9.Li G, Worner M, Lang B, et al. Epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality in the United Sates 1999–2005. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:759–765. doi: 10.1097/aln.0b013e31819b5bdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Quality Forum. 2007. Reportable events in healthcare 2006 update. Consensus Report; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark C. Hospitals fined for forgotten surgical devices, wrong surgeries, burnt patient. Sep 25, 2009. www.healthleadersmedia.com.

- 12.Seiden SC, Barach P. Wrong-side/wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong patient adverse events. Arch Surg. 2006;141:931–939. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meinberg EG, Stern PJ. Incidence of wrong-site surgery among hand surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85-A:193–197. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200302000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahwar BS, Mitsis D, Duggal N. Wrong-sided and wrong level neurosurgery: a national survey. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7(5):467–472. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/11/467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gawande AA, Studdert DM, Orav EJ, et al. Risk factors for retained foreign bodies after surgery. N Eng J Med. 2003;348(3):229–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cima RR, Kollengode A, Garatz J, et al. Incidence and characteristics of potential and actual retained foreign object events in surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(1):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egorva NN, Moskowitz A, Gelijns A, et al. Managing the prevention of retained surgical instruments: What is the value of counting. Ann surg. 2008;247(1):13–18. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180f633be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 320:768–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768. 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gawande AA. The Checklist Manifesto How to get things right. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books. Henry Holt and Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neily J, Mills PD, Eldridge N, et al. Incorrect surgical procedures within and outside of the operating room. Arch Surg. 2009;144(11):1028–1034. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makary MA, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, et al. Operating room briefings and wrong site surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(2):236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzzocco K, Petitti DB, Fong KT, et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markay MA, sexton JB, Freischag JA, et al. Operating room team work among physicians and nurses: teamwork in the eye of the beholder. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(5):746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Eng J Med. 2009;360(5):491–499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark Julia., editor. The “How to” Guide for Reducing Harm in Perioperative Care. www.patientsafetyfirst.Nhs.uk.