Abstract

Schizotypy is defined as a time-stable multidimensional personality trait consisting of positive, negative, and disorganized facets. Schizotypy is considered as a model system of psychosis, as there is considerable overlap between the 2 constructs. High schizotypy is associated with subtle but fairly widespread cognitive alterations, which include poorer performance in tasks measuring cognitive control. Similar but more pronounced impairments in cognitive control have been described extensively in psychosis. We here sought to provide a quantitative estimation of the effect size of impairments in schizotypy in the updating, shifting, and inhibition dimensions of cognitive control. We included studies of healthy adults from both general population and college samples, which used either categorical or correlative designs. Negative schizotypy was associated with significantly poorer performance on shifting (g = 0.32) and updating (g = 0.11). Positive schizotypy was associated with significantly poorer performance on shifting (g = 0.18). There were no significant associations between schizotypy and inhibition. The divergence in results for positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy emphasizes the importance of examining relationships between cognition and the facets of schizotypy rather than using the overall score. Our findings also underline the importance of more detailed research to further understand and define this complex personality construct, which will also be of importance when applying schizotypy as a model system for psychosis.

Keywords: psychosis, schizotypy, executive functions, attention, working memory, inhibition

Introduction

Schizotypy is a time-stable multidimensional personality trait consisting of positive facets, such as unusual perceptual experiences and ideas of reference, negative facets, such as no close friends and flat affect and disorganized facets, such as odd speech and eccentric behavior.1–3 In addition, schizotypy can be quantified as an overall score derived from the combination of these subfacets (“mixed schizotypy”).4

The scientific investigation of schizotypy is mainly motivated by 2 aspects. Firstly, following a personality-based approach allows the exploration of the underlying mechanisms of schizotypy to further our understanding of this complex cluster of traits.5,6 Secondly, following a clinical approach allows to examine clinical implications of high levels of schizotypy and to evaluate the role of schizotypy within the spectrum of psychosis.7 For instance, it has been shown that high schizotypy is associated with self-reports of poor quality of life8 and higher drug use.9 Moreover, as there is considerable overlap in the clinical picture of schizotypy and schizophrenia,7,10,11 it has been suggested that schizotypy can serve as a model system of psychosis, allowing the investigation of psychosis in the absence of potential confounds such as medication or hospitalization.10,11 Following this approach, variation in schizotypy as well as its covariation with cognitive, neural, and behavioral measures has been studied with the objective to elucidate the etiology of psychosis.3,12–15

Evidence from both correlational (making full use of variance in schizotypy scores) and categorical (allocating individuals to discrete groups on the basis of schizotypy scores) studies suggests subtle yet fairly widespread cognitive alterations in high schizotypy,6 including poorer performance in tasks measuring cognitive control.16–25 Cognitive control, or executive function, involves the domain-independent representation and maintenance of task goals, thereby supporting the flexible adaptation of information processing and behavior in a changing environment. Importantly, cognitive control refers to a heterogeneous set of functions. An influential model argues that cognitive control involves 3 overlapping yet separable dimensions, namely shifting, updating, and inhibition.26Shifting involves the flexible switching of attention between tasks or mental sets. Updating refers to the flexible updating as well as monitoring of information in working memory. Inhibition refers to the ability to withhold a nondesirable response that is dominant or prepotent.

Impairments in cognitive control are a cardinal feature of schizophrenia,27 with recent research efforts focusing on the measurement of cognitive control functions to improve both the classification of psychopathology28 and pharmacological treatment.29,30 Given the importance of cognitive control deficits in psychosis,28–30 they are a key target for research aiming to validate schizotypy as a model system.7,15

Although there is evidence of cognitive control impairments in high schizotypy,16,31 some studies could not replicate these findings.22,32,33 A recent meta-analysis by Chun et al8 concluded that high schizotypy in university samples was associated with somewhat poorer performance in set shifting (shifting) and working memory (updating) tasks, while other cognitive features, such as attention and memory, were intact.8

Extending this previous work, we carried out comprehensive meta-analyses of studies reporting associations between schizotypy and inhibition, shifting, and updating. We restricted our definition of schizotypy to psychometric instruments10 such as the SPQ,34 but did not include clinical symptom rating scales, eg, Paranoia Checklist.35 To avoid bias due to sampling strategies, we included all studies that investigated these cognitive control dimensions in relation to schizotypy, irrespective of whether they used correlational or categorical designs. Moreover, we included studies irrespective of whether participants were drawn from university or general community samples to avoid selection bias.

Method

Literature Search

Following the PRISMA guidelines,36 we identified relevant published studies by searching the electronic database PubMed for combinations of the keywords “schizotypy” or “psychosis proneness” and their variations with the keywords “cognition” or “neuropsychology” and their variations as well as more specific terms such as “working memory,” “response inhibition,” “set shifting,” and “executive functions.” The full search term can be found in the supplementary materials. Relevant studies that were published before July 19, 2017 were included in the current analyses.

Study Selection

For studies to be included in the meta-analyses, the following inclusion criteria had to be fulfilled. First, they were required to report performance on a task measuring shifting (eg, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WCST, Trail Making Test; TMT), updating (eg, n-back, spatial working memory tasks), or inhibition (eg, Stroop task, antisaccade task, Stop-Signal task). Second, sufficient data needed to be reported or made available upon request to allow the quantification of the relationship between performance and schizotypy (standardized mean difference or correlation). Review articles not reporting original data or articles reporting single case studies were excluded. Third, schizotypal personality scores had to be obtained via psychometric questionnaires (eg, Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire,34 SPQ; Chapman psychosis-proneness scales37–39; Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences,1 O-LIFE) irrespective of how commonly the questionnaire was used. Fourth, the sample had to consist of healthy participants. Thus, for patient studies only healthy control groups were included. Fifth, the sample had to comprise adults only. Sixth, the article had to be published in an English language journal with peer review.

Our conceptualization of schizotypy should be distinguished from the symptom oriented approach proposed by van Os and Reininghaus,40 although the 2 approaches may in fact be related.41 To maximize homogeneity in the conceptualization of schizotypy in our analyses, we included only studies that employed psychometric instruments for measuring schizotypy,10 eg, the SPQ34 and did not include clinical symptom rating scales, eg, the Paranoia Checklist.35

To provide a comprehensive summary of the literature, we did not limit inclusion of tasks measuring cognitive control to those used by Miyake et al,26 but included other tasks that we considered to measure the relevant dimensions. We decided in consensus which tasks were to be included in the analyses. An exhaustive list of all tasks included can be found in the supplementary materials.

Data Extraction and Computation of Effect Sizes

The main outcome measure was the relationship between cognitive task performance and schizotypal personality scores. Data extraction was performed by M.S. and I.M. and verified by K.F. and P.K. (see Acknowledgments section). When studies compared performance between individuals with high schizotypy and individuals with low or medium schizotypy, relevant data were extracted to enable a computation of the standardized mean effect Hedges’ g.42 When studies reported a relationship between performance scores and schizotypal personality scores, correlation coefficients were extracted and converted to Hedges’ g.42 The variance of g was estimated for all included studies.42 Computation of Hedges’ g and its variance was carried out blindly by purpose-written routines in Matlab (MathWorks, version 2014a).

For studies that reported categorical and correlative outcomes, the group results were included in the meta-analyses. For studies with categorical designs that investigated more than 2 groups (ie, low, average, high) the most extreme groups were selected for further computations.

To assure the validity of effect size conversion from correlation coefficients to Hedges’ g, we tested the conversion using studies that provided both correlation coefficients and Hedges’ g measures. To assure the validity of combining effect sized from studies employing different designs (correlational, categorical), we performed moderator-analyses (separate meta-analyses for categorical and correlational design studies) for the variable study design as well as sensitivity analyses. Results of the sensitivity analyses are reported in supplementary table 1. Despite this potential risk of bias, effect size conversion is the preferred strategy in comparison to the exclusion of studies using an alternate metric which would be associated with a systematic loss of information.

We contacted the authors of articles that did not report the necessary data. Studies were excluded from our analysis whenever data to calculate effect sizes were not available. Furthermore, where reported, the following additional information was extracted: year of publication, schizotypy questionnaire, and sample type (community, college).

Computation of Meta-analyses and Moderator Effects

Following Viechtbauer,43 the overall effect size was calculated using a random-effects-model with the restricted maximum-likelihood method to estimate heterogeneity in the population effect sizes. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated using the Q-test.44 As the 3-parameter selection model has been reported to outperform other bias correcting methods,45 the presence of publication bias was explored by the weight-function model of Vevea et al.46,47 All analyses were performed using the R software for statistical computation (version 3.4.1)48 and the software packages metafor49 and weightr.47

Separate meta-analyses were conducted for each of the 3 cognitive domains (updating, shifting, inhibition) and each of the 3 schizotypy dimensions (positive, negative, disorganized). Additionally, we conducted meta-analyses for the 3 cognitive domains and schizotypy measured as an overall score (comprised of a combination of the schizotypy facets). Whenever a study had more than one outcome for one of the investigated cognitive domains or schizotypy dimensions, the corresponding effect sizes were averaged. We assumed K >8 studies as a sufficient size to conduct a meta-analysis. We chose this conservative threshold on the basis of the potential heterogeneity (tasks, schizotypy measures employed) and previous meta-analyses8 to avoid potential misinterpretations.

To further assess the influence of year of publication, study design (categorical, correlation), and sample type (community, college), these variables were included into the model as moderators. For information about which study employed which study design and sample type refer to supplementary table 4. If more than one dimension of schizotypy was significantly associated with a cognitive domain, we conducted an additional moderator analysis as follows: We computed a meta-analysis for all studies of these schizotypy dimensions with that cognitive domain and used the schizotypy dimension as a moderator.

Results

Literature Search

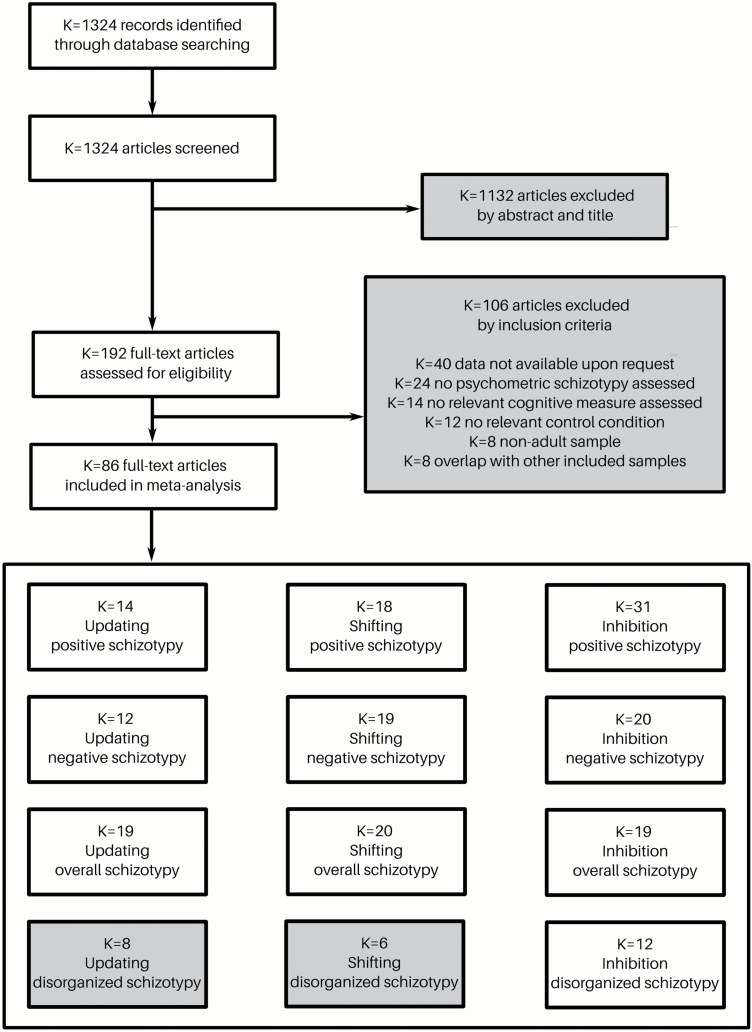

The detailed selection process and all exclusion criteria can be found in figure 1. Our literature search identified K = 1324 potentially relevant articles. After excluding K = 1132 articles based on their abstract and title, the full texts of the remaining K = 192 articles were assessed for eligibility. This procedure resulted in K = 86 articles that were included in the meta-analyses. Some studies could be assigned to more than one of the cognitive dimensions and some studies could be assigned to more than one of the schizotypy dimensions. An overview of the results for all conducted meta-analyses can be found in figure 2. For an overview of the tasks used in each analysis, please refer to supplementary table 3. For an overview of all questionnaires employed in the included studies, please refer to supplementary table 2.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram shows the process of study inclusion and exclusion for the meta-analysis, including all exclusion criteria.

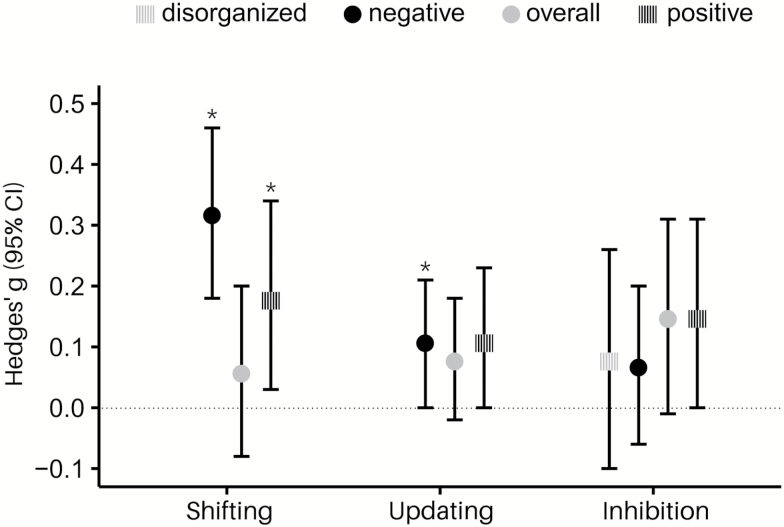

Fig. 2.

Overview of all conducted meta-analyses, y-axis displays mean Hedges’ g and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

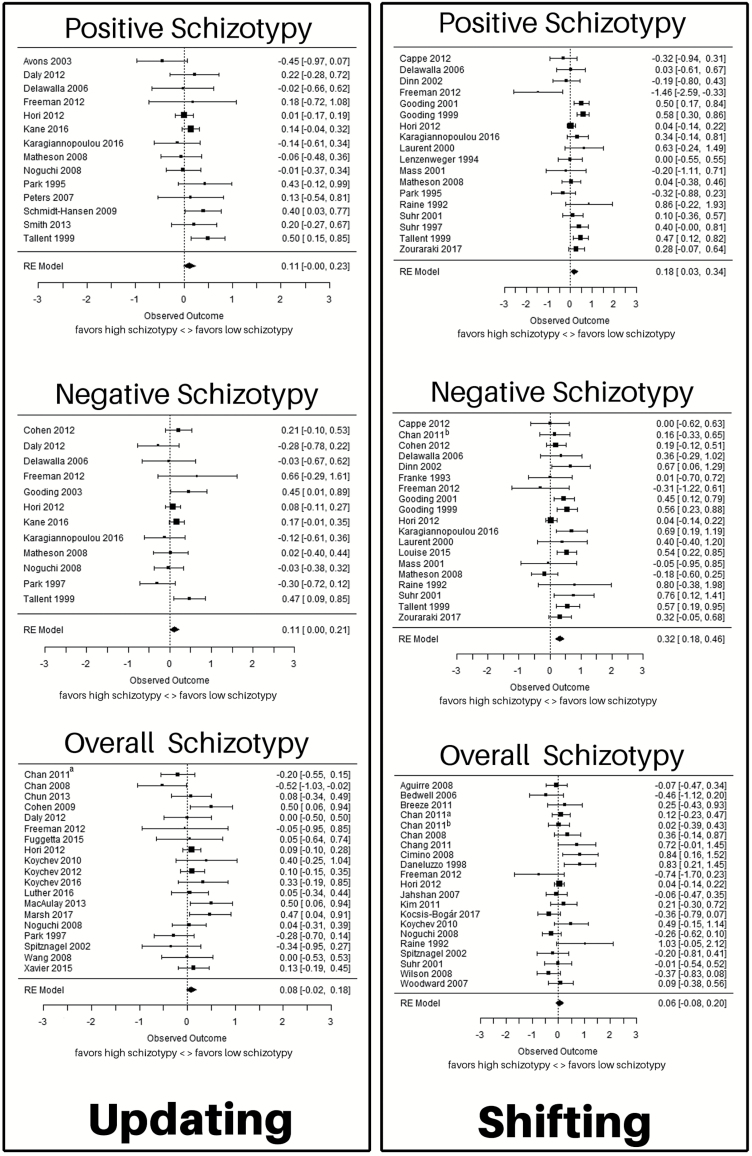

Updating

Thirty-three studies investigated the relationship between schizotypy and updating. We conducted separate meta-analyses for positive, negative, and overall schizotypy. There were not enough studies to conduct a meta-analysis for disorganized schizotypy (K = 8).19,33,50–55 Results are reported in table 1 and illustrated in figure 3.

Table 1.

Overview of Meta-analytic Results

| Number of Studies Included (K) | Number of Subjects Included (N) | Hedges’ g (SE) | z (P) | 95% CI | Q total (P) | χ2 (P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Updating | ||||||||

| Positive schizotypy | 14 | 1894 | 0.11 (0.06) | 1.90 (.06) | −0.004 | 0.23 | 16.66 (.22) | 0.83 (.66) |

| Negative schizotypy | 12 | 1772 | 0.11 (0.05) | 2.03 (.04)* | 0.004 | 0.21 | 15.83 (.15) | 2.13 (.34) |

| Overall schizotypy | 19 | 2075 | 0.08 (0.05) | 1.50 (.13) | −0.02 | 0.18 | 24.82 (.13) | 6.57 (.04) |

| Shifting | ||||||||

| Positive schizotypy | 18 | 1692 | 0.18 (0.08) | 2.30 (.02)* | 0.03 | 0.34 | 37.40 (.003) | 0.14 (.93) |

| Negative schizotypy | 19 | 1846 | 0.32 (0.07) | 4.56 (<.0001)* | 0.18 | 0.46 | 30.83 (.03) | 0.95 (.62) |

| Overall schizotypy | 21 | 1708 | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.84 (.40) | −0.08 | 0.20 | 37.70 (.01) | 1.41 (.49) |

| Inhibition | ||||||||

| Positive schizotypy | 31 | 4284 | 0.15 (0.08) | 1.91 (.06) | −0.004 | 0.31 | 100.04 (<.0001) | 2.29 (.32) |

| Negative schizotypy | 20 | 3503 | 0.07 (0.07) | 1.05 (.29) | −0.06 | 0.20 | 35.67 (.01) | 1.81 (.40) |

| Overall schizotypy | 19 | 2605 | 0.15 (0.08) | 1.79 (.07) | −0.01 | 0.31 | 35.84 (.007) | 0.12 (.94) |

| Disorganized schizotypy | 12 | 2900 | 0.08 (0.09) | 0.85 (.40) | −0.10 | 0.26 | 27.17 (.004) | 0.72 (.70) |

Note: SE, standard error of the mean; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for the meta-analyses for the relationship between positive, negative, and overall schizotypy and updating and shifting, respectively. The figure shows effect size (Hedges’ g) and confidence intervals for all included studies. Studies are ordered alphabetically by last name of first author. Sample size is illustrated through the size of the square. The 95% confidence intervals are reflected in the length of the horizontal lines. Source: Chan (2011)a65; Chan (2011)b84.

The SPQ was used in 20 studies, the Chapman psychosis-proneness scales were used in 7 studies, the O-LIFE was used in 6 studies, and the Cognitive Slippage Scale and the Schizotypal Personality scale (STA) were used in 1 study each. For an overview of the tasks used in the analyses, please refer to supplementary table 3.

Positive Schizotypy

Fourteen studies19,22,33,50–52,55–62 including 1894 participants were included. There was no significant effect of positive schizotypy on updating, with an average effect size of g = 0.11 (z = 1.90, P = .06). There was no publication bias (P = .66) and none of the moderators had a significant effect (all P ≥ .05).

Negative Schizotypy

Twelve studies17,19,22,33,50–52,55,57,62–64 including 1772 participants were included. There was a significant effect of negative schizotypy on updating, yielding an average effect size of g = 0.11 (z = 2.03, P = .04). There was no publication bias (P = .34) and none of the moderators had a significant effect (all P ≥ .06).

Overall Schizotypy

Nineteen studies4,8,17,18,33,50,51,55,65–75 including 2075 participants were included. There was no significant effect of overall schizotypy on updating, with an average effect size of g = 0.08 (z = 1.50, P = .13). There was evidence for a potential publication bias (P = .04). Publication year (P = .007), but none of the other moderators, had a significant effect (all P ≥ .30).

Shifting

Thirty-eight studies investigated the relationship between schizotypy and shifting. We conducted separate meta-analyses for positive, negative, and overall schizotypy. There were not enough studies to conduct a meta-analysis for disorganized schizotypy (K = 6).19,32,33,51,76,77 Results are reported in table 1 and illustrated in figure 3.

The SPQ was used in 22 studies, the Chapman psychosis- proneness scales were used in 12 studies, the O-LIFE was used in 4 studies, the STA and the Schizophrenism scale were used in 1 study each and a composite score of several schizotypy scales was used in 2 studies. For an overview of the tasks used in the analyses, please refer to supplementary table 3.

Positive Schizotypy

Eighteen studies19,21,22,24,32,33,51,57,58,62,76–83 including 1692 participants were included. There was a significant effect of positive schizotypy on shifting, yielding an average effect size of g = 0.18 (z = 2.30, P = .02). There was no publication bias (P = .93) and none of the moderators had a significant effect (all P ≥ .27).

Negative Schizotypy

Nineteen studies19,21,22,24,32,33,51,54,57,62,63,76–80,82,84,85 including 1846 participants were included. There was a significant effect of negative schizotypy on shifting, yielding an average effect size of g = 0.32 (z = 4.56, P < .0001). There was no publication bias (P = .62). The study design (P = .04), but none of the other moderators, had an effect on the analysis (all P ≥ .26). If only categorical studies were included in the analysis, the effect increased to g = 0.44 (z = 5.78, P < .0001) and if only correlative studies were included, the effect decreased to 0.18 (z = 1.79, P = .07).

Overall Schizotypy

Twenty-one studies18,21,33,51,55,65,72,73,82,84,86–96 including 1708 participants were included. There was no significant effect of overall schizotypy on shifting, at an average effect size of g = 0.06 (z = 0.84, P = .40). There was no publication bias (P = .49) and none of the moderators had a significant effect (all P ≥ .09).

Comparison Between Negative and Positive Schizotypy

There was no significant moderator effect of schizotypy dimension (positive, negative) for the association between schizotypy score and shifting (P = .20).

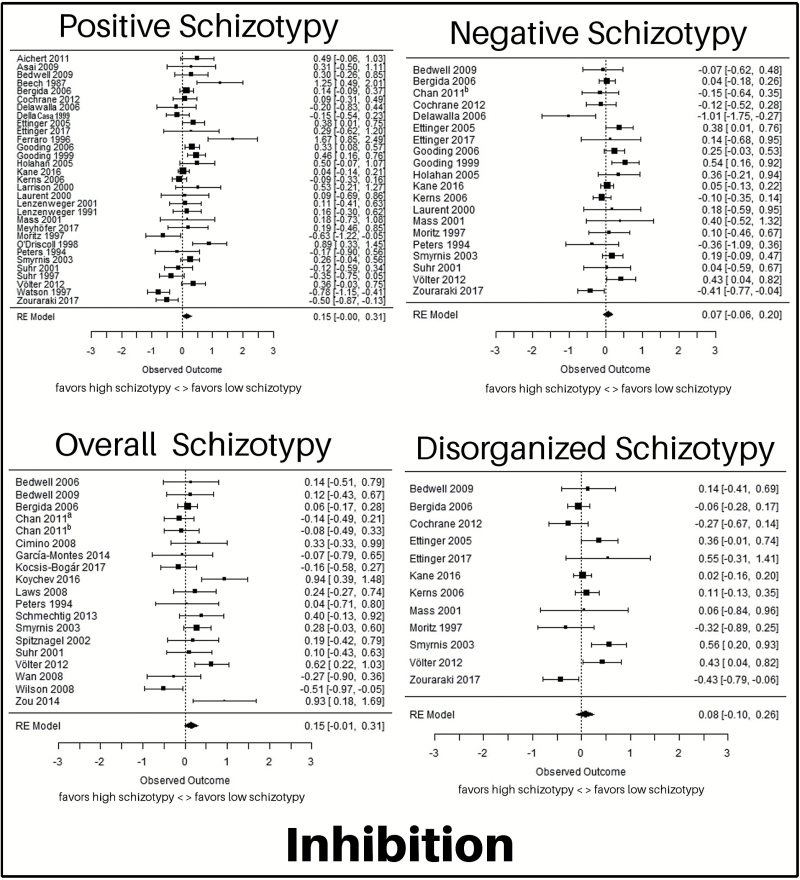

Inhibition

Forty-four studies investigated the relationship between schizotypy and inhibition. We conducted separate meta-analyses for positive, negative, disorganized, and overall schizotypy. Results are reported in table 1 and illustrated in figure 4.

Fig. 4.

Forest plots for the meta-analyses for the relationship between positive, negative, and overall schizotypy and inhibition. The figure shows effect size (Hedges’ g) and confidence intervals for all included studies. Studies are ordered alphabetically by last name of first author. Sample size is illustrated through the size of the square. The 95% confidence intervals are reflected in the length of the horizontal lines. Source: Chan (2011)a65; Chan (2011)b84.

The SPQ was used in 22 studies, the Chapman psychosis-proneness scales were used in 13 studies, the STA was used in 6 studies, the Rust Inventory of Schizotypal Cognitions was used in 4 studies, the O-LIFE was used in 3 studies, the Cognitive Slippage scale, the Oviedo Schizotypy Assessment Questionnaire-Abbreviated, the Personality Syndrome Questionnaire, the Restrictive Emotional Expression scale, and the Schizophrenism scale were used in 1 study each, and a composite score of several schizotypy scales was used in 1 study. For an overview of the tasks used in the analyses, please refer to supplementary table 3.

Positive Schizotypy

Thirty-one studies23,24,32,52,57,77,80,82,83,97–118 including 4284 participants were included. There was no significant effect of positive schizotypy on inhibition, yielding an average effect size of g = 0.15 (z = 1.91, P = .06). There was no publication bias (P = .32) and none of the moderators had a significant effect (all P ≥ .20).

Negative Schizotypy

Twenty studies23,24,32,52,57,77,80,82,84,99,101,102,104,106–108,113,115–117 including 3503 participants were included. There was no significant effect of negative schizotypy on inhibition, yielding an average effect size of g = 0.07 (z = 1.05, P = .29). There was no publication bias (P = .40) and none of the moderators had an effect on the analysis (all P ≥ .07).

Disorganized Schizotypy

Twelve studies23,32,52,77,99,101,102,104,108,113,116,117 including 2900 participants were included. There was no significant effect of disorganized schizotypy on inhibition, yielding an average effect size of g = 0.08 (z = 0.85, P = .40). There was no publication bias (P = .70) and none of the moderators had a significant effect (all P ≥ .05).

Overall Schizotypy

Nineteen studies65,72,75,82,84,87,90,94,95,99,101,115–117,119–123 including 2605 participants were included. There was no significant effect of overall schizotypy on inhibition, yielding an average effect size of g = 0.15 (z = 1.79, P = .07). There was no publication bias (P = .94) and none of the moderators had a significant effect (all P ≥ .16).

Discussion

We investigated the association between schizotypy and dimensions of cognitive control in a comprehensive series of meta-analyses. To do so, we carried out separate analyses for combinations of the updating, shifting, and inhibition dimensions with positive, negative, disorganized, and overall schizotypy. In summary, negative schizotypy was associated with significantly poorer performance on shifting (g = 0.32) and updating (g = 0.11). The association between negative schizotypy and shifting was more pronounced for studies employing a categorical design than for those with a correlative design (g = 0.44 vs g = 0.18). Positive schizotypy was associated with significantly poorer performance on shifting tasks (g = 0.18). There was no significant difference in the strength of the association of positive schizotypy and shifting and negative schizotypy and shifting. There were no significant associations between schizotypy and inhibition. Despite significant heterogeneity in most of the analyses, the moderators that we included (study design, publication year, sample type) had only small effects on the results.

The differences in updating and shifting are in line with findings by Chun et al.8 Importantly, our analyses extend those by Chun et al8 beyond student populations and to a more comprehensive assessment of cognitive control and schizotypy. The deficits in cognitive control that we observed were most pronounced in relation to negative schizotypy. This finding is in line with literature discussing the negative dimension as a primary feature of schizotypy.124 Negative schizotypy is the most heritable dimension and has been associated with poorer quality of life, poorer well-being, and higher levels of perceived stress.6,124,125 The divergent results for the schizotypy facets reported here emphasize the importance of examining relationships between cognitive variables and the 3 facets of schizotypy rather than combining them into an overall score. While positive and negative schizotypy were associated with poorer performance in updating and shifting, we found no such association for overall (“mixed”) schizotypy. It should be noted that overall schizotypy is characterized by a mix of features from all domains and, therefore, may comprise a different population which seems, on the basis of our analyses, not to be associated with impairments in cognitive control. In terms of clinical implications, high schizotypy has been shown to be associated with impoverished quality of life.8,126 It stands to reason that the small impairments on shifting and updating found here are not severe enough to explain this relationship. Some evidence suggests that impaired social cognition, such as emotional face recognition, may have a larger impact on quality of life.127

With regards to schizotypy as a psychosis model system, in the present analysis individuals with high schizotypy showed somewhat similar deficits as those reported in schizophrenia, albeit to a much lower extent. Average effect sizes reported for schizophrenia patients on updating, shifting, and inhibition range from g = 0.86 to g = 0.99.128 This is in line with findings that most features that overlap between schizotypy and schizophrenia are less pronounced in schizotypy.7 This further underlines schizotypy as a useful tool to study etiological mechanisms of psychosis as well as possible protective factors,11 without the confounds such as medication and hospitalization14 typically encountered in patient samples.

Between-study heterogeneity was moderate to high for all analyses of the inhibition dimension, in line with findings that associations between tasks measuring inhibition are rather low.129 This may make the detection of associations between this heterogeneous construct and schizotypy more challenging. In terms of schizotypy as a model system this suggests that schizotypy does not mimic all features of psychosis. To some extent this is true for all model systems.130 However, considering the complexity of psychosis, it might be challenging for one single model to mimic all features of this heterogeneous disorder.131 Defining the limitations of existing model systems can improve our understanding of specific etiological mechanisms underlying psychotic symptoms. Additionally, it would be desirable to distinguish subfacets of inhibition and to investigate their association with schizotypy.

Our findings of somewhat overlapping impairments in schizophrenia and schizotypy are not of course proof of similar etiological factors. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis, that schizotypy and schizophrenia are 2 completely unrelated phenomena that both independently, via different molecular and cellular mechanisms, lead to impairments in cognitive control, has to be considered carefully.

A strength of our study is its comprehensiveness: We comprehensively quantified the influence of schizotypy facets as well as its total score on 3 key dimensions of cognitive control. To avoid bias due to sampling strategies, we included all studies that investigated these cognitive processes in relation to schizotypy, irrespective of whether they used correlational or categorical designs. Moreover, we included studies irrespective of whether participants were drawn from university or general community samples to avoid selection bias.

One limitation of our analyses might be that we included different measures of schizotypy. We did this to avoid sampling bias; however, this comes with the risk of increased heterogeneity of the studies included in our analyses. A second limitation is that we combined effect sizes from correlational and categorical studies. While this approach has the benefit of precluding systematic loss of information due to study exclusion, it may potentially lead to bias in our analyses. We addressed this potential bias by computing moderator analyses for the study design variable. Study design was only a significant moderator in the association between negative schizotypy and shifting, where the association was stronger for categorical than correlational studies. To further address this issue, we conducted separate analyses for categorical and correlational studies (sensitivity analysis, results reported in supplementary table 1), and found that effects tended to be higher for categorical than correlational studies overall. This is an important methodological implication for the interpretation of studies reporting associations between schizotypy and cognitive control. Finally, our meta-analysis did not of course provide a characterization of all cognitive impairments in schizotypy. Instead, we focused, on the basis of prior work,30 on cognitive control as a central human cognitive function. Further meta-analyses are required to provide similar estimations of the magnitude of impairment in schizotypy in other domains and stages of information processing.

In summary, our analyses revealed subtle cognitive control deficits in high schizotypy. These were most pronounced in negative schizotypy, which was associated with impairments in the updating and shifting dimensions. The divergent results for positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy reported here emphasize the importance of examining relationships between cognitive variables and the 3 facets of schizotypy rather than combining them to an overall score. Effects on cognitive control similar to those reported here have been described extensively in psychosis, although effects in patients generally are larger. Our findings underline the importance of more detailed research to further understand and define this complex personality construct, which will also be of importance when applying schizotypy research as a model system for psychosis. Such research may focus on direct comparisons between psychosis patients and schizotypy, comparisons between the different dimensions of schizotypy as well as a differential approach to executive function and its features.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Schizophrenia Bulletin online.

Acknowledgments

We would like to gratefully acknowledge all authors who generously provided required data for the meta-analysis. We would like to thank Pamela Küpper (P.K.) for her help in the verification of extracted data and Verena Oberlader for her help with data analysis. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Mason O, Claridge G, Jackson M. New scales for the assessment of schizotypy. 1995;18:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raine A, Reynolds C, Lencz T, Scerbo A, Triphon N, Kim D. Cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal, and disorganized features of schizotypal personality. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raine A. Schizotypal personality: neurodevelopmental and psychosocial trajectories. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:291–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan RCK, Wang Y, Ma Z et al. Objective measures of prospective memory do not correlate with subjective complaints in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;103:229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen AS, Mohr C, Ettinger U, Chan RC, Park S. Schizotypy as an organizing framework for social and affective sciences. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(suppl 2):S427–S435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohr C, Claridge G. Schizotypy—do not worry, it is not all worrisome. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(suppl 2):S436–S443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ettinger U, Meyhöfer I, Steffens M, Wagner M, Koutsouleris N. Genetics, cognition, and neurobiology of schizotypal personality: a review of the overlap with schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chun CA, Minor KS, Cohen AS. Neurocognition in psychometrically defined college schizotypy samples: we are not measuring the “right stuff”. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2013;19:324–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Najolia GM, Buckner JD, Cohen AS. Cannabis use and schizotypy: the role of social anxiety and other negative affective states. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:660–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mason OJ. The assessment of schizotypy and its clinical relevance. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(suppl 2):S374–S385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barrantes-Vidal N, Grant P, Kwapil TR. The role of schizotypy in the study of the etiology of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(suppl 2):408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meehl PE. Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. Am Psychol. 1962;17:827–838. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meehl PE. Schizotaxia revisited. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:935–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lenzenweger M. Schizotypy and Schizophrenia: The View from Experimental Psychopathology. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nelson MT, Seal ML, Pantelis C, Phillips LJ. Evidence of a dimensional relationship between schizotypy and schizophrenia: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ettinger U, Mohr C, Gooding DC et al. Cognition and brain function in schizotypy: a selective review. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(suppl 2):417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park S, Mctigue K. Working memory and the syndromes of schizotypal personality. Schizophr Res. 1997;26:213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koychev I, El-Deredy W, Haenschel C, Deakin JF. Visual information processing deficits as biomarkers of vulnerability to schizophrenia: an event-related potential study in schizotypy. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:2205–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matheson S, Langdon R. Schizotypal traits impact upon executive working memory and aspects of IQ. Psychiatry Res. 2008;159:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gooding DC, Kwapil TR, Tallent KA. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test deficits in schizotypic individuals. Schizophr Res. 1999;40:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raine A, Sheard C, Reynolds GP, Lencz T. Pre-frontal structural and functional deficits associated with individual differences in schizotypal personality. Schizophr Res. 1992;7:237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karagiannopoulou L, Karamaouna P, Zouraraki C, Roussos P, Bitsios P, Giakoumaki SG. Cognitive profiles of schizotypal dimensions in a community cohort: common properties of differential manifestations. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2016;38:1050–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ettinger U, Kumari V, Crawford TJ et al. Saccadic eye movements, schizotypy, and the role of neuroticism. Biol Psychol. 2005;68:61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gooding DC. Antisaccade task performance in questionnaire-identified schizotypes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O’Driscoll GA, Lenzenweger MF, Holzman PS. Antisaccades and smooth pursuit eye tracking and schizotypy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:837–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol. 2000;41:49–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM et al. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morris SE, Cuthbert BN. Research Domain Criteria: cognitive systems, neural circuits, and dimensions of behavior. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carter CS, Barch DM. Cognitive neuroscience-based approaches to measuring and improving treatment effects on cognition in schizophrenia: the CNTRICS initiative. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1131–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lesh TA, Niendam TA, Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: mechanisms and meaning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:316–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Giakoumaki SG. Cognitive and prepulse inhibition deficits in psychometrically high schizotypal subjects in the general population: relevance to schizophrenia research. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18:643–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zouraraki C, Karamaouna P, Karagiannopoulou L, Giakoumaki SG. Schizotypy-independent and schizotypy-modulated cognitive impairments in unaffected first-degree relatives of schizophrenia-spectrum patients. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;32:1010–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Freeman TP, Morgan CJ, Vaughn-Jones J, Hussain N, Karimi K, Curran HV. Cognitive and subjective effects of mephedrone and factors influencing use of a ‘new legal high’. Addiction. 2012;107:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Freeman D, Garety PA, Bebbington PE et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1976;85:374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eckblad M, Chapman LJ. Magical ideation as an indicator of schizotypy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Body-image aberration in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1978;87:399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Os J, Reininghaus U. Psychosis as a transdiagnostic and extended phenotype in the general population. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van’t Wout M, Aleman A, Kessels RPC, Larøi F, Kahn RS. Emotional processing in a non-clinical psychosis-prone sample. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Borenstein M. Effect sizes for continuous data. In: Cooper H, Hedges L, Valentine J, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 2009:221–235. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Viechtbauer W. Bias and efficiency of meta-analytic variance estimators in the random-effects model. J Educ Behav Stat. 2005;30:261–293. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carter E, Schönbrodt F, Gervais W, Hilgard J. Correcting for bias in psychology: a comparison of meta-analytic methods https://osf.io/rf3ys/.

- 46. Vevea JL, Hedges LV. A general linear model for estimating effect size in the presence of publication bias. Psychometrika. 1995;60:419–435. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vevea JL, Woods CM. Publication bias in research synthesis: sensitivity analysis using a priori weight functions. Psychol Methods. 2005;10:428–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. R-Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. http://www.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Daly MP, Afroz S, Walder DJ. Schizotypal traits and neurocognitive functioning among nonclinical young adults. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hori H, Teraishi T, Sasayama D et al. Relationships between season of birth, schizotypy, temperament, character and neurocognition in a non-clinical population. Psychiatry Res. 2012;195:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kane MJ, Meier ME, Smeekens BA et al. Individual differences in the executive control of attention, memory, and thought, and their associations with schizotypy. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2016;145:1017–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kerns JG, Becker TM. Communication disturbances, working memory, and emotion in people with elevated disorganized schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:172–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Louise S, Gurvich C, Neill E, Tan EJ, Van Rheenen TE, Rossell S. Schizotypal traits are associated with poorer executive functioning in healthy adults. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Noguchi H, Hori H, Kunugi H. Schizotypal traits and cognitive function in healthy adults. Psychiatry Res. 2008;161:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Avons SE, Nunn JA, Chan L, Armstrong H. Executive function assessed by memory updating and random generation in schizotypal individuals. Psychiatry Res. 2003;120:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Delawalla Z, Barch DM, Fisher Eastep JL et al. Factors mediating cognitive deficits and psychopathology among siblings of individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:525–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Park S, Holzman PS, Lenzenweger MF. Individual differences in spatial working memory in relation to schizotypy. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Peters MJ, Smeets T, Giesbrecht T, Jelicic M, Merckelbach H. Confusing action and imagination: action source monitoring in individuals with schizotypal traits. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:752–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schmidt-Hansen M, Honey RC. Working memory and multidimensional schizotypy: dissociable influences of the different dimensions. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2009;26:655–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Smith NT, Lenzenweger MF. Increased stress responsivity in schizotypy leads to diminished spatial working memory performance. Personal Disord. 2013;4:324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tallent KA, Gooding DC. Working memory and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance in schizotypic individuals: a replication and extension. Psychiatry Res. 1999;89:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cohen AS, Couture SM, Blanchard JJ. Neuropsychological functioning and social anhedonia: three-year follow-up data from a longitudinal community high risk study. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gooding DC, Tallent KA. Spatial, object, and affective working memory in social anhedonia: an exploratory study. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chan RCK, Wang Y, Yan C et al. Contribution of specific cognitive dysfunction to people with schizotypal personality. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186:71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cohen AS, Iglesias B, Minor KS. The neurocognitive underpinnings of diminished expressivity in schizotypy: what the voice reveals. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fuggetta G, Bennett MA, Duke PA. An electrophysiological insight into visual attention mechanisms underlying schizotypy. Biol Psychol. 2015;109:206–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Koychev I, McMullen K, Lees J et al. A validation of cognitive biomarkers for the early identification of cognitive enhancing agents in schizotypy: a three-center double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22:469–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Luther L, Salyers MP, Firmin RL, Marggraf MP, Davis B, Minor KS. Additional support for the cognitive model of schizophrenia: evidence of elevated defeatist beliefs in schizotypy. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;68:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. MacAulay R, Cohen AS. Affecting coping: does neurocognition predict approach and avoidant coping strategies within schizophrenia spectrum disorders?Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Marsh JE, Vachon F, Sörqvist P. Increased distractibility in schizotypy: independent of individual differences in working memory capacity?Q J Exp Psychol (Hove). 2017;70:565–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Spitznagel MB, Suhr JA. Executive function deficits associated with symptoms of schizotypy and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2002;110:151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang Y, Chan RC, Xin Yu, Shi C, Cui J, Deng Y. Prospective memory deficits in subjects with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a comparison study with schizophrenic subjects, psychometrically defined schizotypal subjects, and healthy controls. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Xavier S, Best MW, Schorr E, Bowie CR. Neurocognition, functional competence and self-reported functional impairment in psychometrically defined schizotypy. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2015;20:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Koychev I, Joyce D, Barkus E et al. Cognitive and oculomotor performance in subjects with low and high schizotypy: implications for translational drug development studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cappe C, Herzog MH, Herzig DA, Brand A, Mohr C. Cognitive disorganisation in schizotypy is associated with deterioration in visual backward masking. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:652–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mass R, Bardong C, Kindl K, Dahme B. Relationship between cannabis use, schizotypal traits, and cognitive function in healthy subjects. Psychopathology. 2001;34:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dinn WM, Harris CL, Aycicegi A, Greene P, Andover MS. Positive and negative schizotypy in a student sample: neurocognitive and clinical correlates. Schizophr Res. 2002;56:171–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gooding DC, Tallent KA, Hegyi JV. Cognitive slippage in schizotypic individuals. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:750–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Laurent A, Biloa-tang M, Bougerol T et al. Executive/attentional performance and measures of schizotypy in patients with schizophrenia and in their nonpsychotic first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res. 2000;46:269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lenzenweger MF, Korfine L. Perceptual aberrations, schizotypy, and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Suhr JA, Spitznagel MB. Factor versus cluster models of schizotypal traits. II: relation to neuropsychological impairment. Schizophr Res. 2001;52:241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Suhr JA. Executive functioning deficits in hypothetically psychosis-prone college students. Schizophr Res. 1997;27:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Chan RC, Yan C, Qing YH et al. Subjective awareness of everyday dysexecutive behavior precedes ‘objective’ executive problems in schizotypy: a replication and extension study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Franke P, Maier W, Hardt J, Hain C. Cognitive functioning and anhedonia in subjects at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1993;10:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Aguirre F, Sergi MJ, Levy CA. Emotional intelligence and social functioning in persons with schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 2008;104:255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bedwell JS, Kamath V, Baksh E. Comparison of three computer-administered cognitive tasks as putative endophenotypes of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;88:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Breeze JM, Kirkham AJ, Marí-Beffa P. Evidence of reduced selective attention in schizotypal personality disorder. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33:776–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Chang TG, Lee IH, Chang CC et al. Poorer Wisconsin card-sorting test performance in healthy adults with higher positive and negative schizotypal traits. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:596–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Cimino M, Haywood M. Inhibition and facilitation in schizotypy. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2008;30:187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Daneluzzo E, Bustini M, Stratta P, Casacchia M, Rossi A. Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in a population of DSM-III-R schizophrenic patients and control subjects. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jahshan CS, Sergi MJ. Theory of mind, neurocognition, and functional status in schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 2007;89:278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kim MS, Oh SH, Hong MH, Choi DB. Neuropsychologic profile of college students with schizotypal traits. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kocsis-Bogár K, Kotulla S, Maier S, Voracek M, Hennig-Fast K. Cognitive correlates of different mentalizing abilities in individuals with high and low trait schizotypy: findings from an extreme-group design. Front Psychol. 2017;8:922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wilson CM, Christensen BK, King JP, Li Q, Zelazo PD. Decomposing perseverative errors among undergraduates scoring high on the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Woodward TS, Buchy L, Moritz S, Liotti M. A bias against disconfirmatory evidence is associated with delusion proneness in a nonclinical sample. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Aichert DS, Williams SC, Möller HJ, Kumari V, Ettinger U. Functional neural correlates of psychometric schizotypy: an fMRI study of antisaccades. Psychophysiology. 2012;49:345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Asai T, Sugimori E, Tanno Y. Schizotypal personality traits and prediction of one’s own movements in motor control: what causes an abnormal sense of agency?Conscious Cogn. 2008;17:1131–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bedwell JS, Kamath V, Compton MT. The relationship between interview-based schizotypal personality dimension scores and the continuous performance test. Schizophr Res. 2009;108:158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Beech A, Claridge G. Individual differences in negative priming: relations with schizotypal personality traits. Br J Psychol. 1987;78(Pt 3):349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bergida H, Lenzenweger MF. Schizotypy and sustained attention: confirming evidence from an adult community sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Cochrane M, Petch I, Pickering AD. Aspects of cognitive functioning in schizotypy and schizophrenia: evidence for a continuum model. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Della Casa V, Höfer I, Weiner I, Feldon J. Effects of smoking status and schizotypy on latent inhibition. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13:45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ettinger U, Aichert DS, Wöstmann N, Dehning S, Riedel M, Kumari V. Response inhibition and interference control: effects of schizophrenia, genetic risk, and schizotypy. J Neuropsychol. 2017. doi:10.1111/jnp.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Ferraro FR, Okerlund M. Failure to inhibit irrelevant information in non-clinical schizotypal individuals. J Clin Psychol. 1996;52:389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Gooding DC, Matts CW, Rollmann EA. Sustained attention deficits in relation to psychometrically identified schizotypy: evaluating a potential endophenotypic marker. Schizophr Res. 2006;82:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Holahan AL, O’Driscoll GA. Antisaccade and smooth pursuit performance in positive- and negative-symptom schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kerns JG. Schizotypy facets, cognitive control, and emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Larrison AL, Ferrante CF, Briand KA, Sereno AB. Schizotypal traits, attention and eye movements. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2000;24:357–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lenzenweger MF. Reaction time slowing during high-load, sustained-attention task performance in relation to psychometrically identified schizotypy. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Lenzenweger MF, Cornblatt BA, Putnick M. Schizotypy and sustained attention. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Meyhöfer I, Steffens M, Faiola E, Kasparbauer AM, Kumari V, Ettinger U. Combining two model systems of psychosis: the effects of schizotypy and sleep deprivation on oculomotor control and psychotomimetic states. Psychophysiology. 2017;54:1755–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Moritz S, Mass R. Reduced cognitive inhibition in schizotypy. Br J Clin Psychol. 1997;36(Pt 3):365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Driscoll GAO, Strakowski SM, Alpert NM et al. Differences in cerebral activation during smooth pursuit and saccadic eye movements using positron-emission tomography. 1998;3223:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Peters ER, Pickering AD, Hemsley DR. ‘Cognitive inhibition’ and positive symptomatology in schizotypy. Br J Clin Psychol. 1994;33(Pt 1):33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Smyrnis N, Evdokimidis I, Stefanis NC et al. Antisaccade performance of 1,273 men: effects of schizotypy, anxiety, and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Völter C, Strobach T, Aichert DS et al. Schizotypy and behavioural adjustment and the role of neuroticism. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Watson FL, Tipper SP. Brief report reduced negative priming in schizotypal subjects does reflect reduced cognitive inhibition. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 1997;2:67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. García-Montes JM, Noguera C, Alvarez D, Ruiz M, Cimadevilla Redondo JM. High and low schizotypal female subjects do not differ in spatial memory abilities in a virtual reality task. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2014;19:427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Laws KR, Patel DD, Tyson PJ. Awareness of everyday executive difficulties precede overt executive dysfunction in schizotypal subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Schmechtig A, Lees J, Grayson L et al. Effects of risperidone, amisulpride and nicotine on eye movement control and their modulation by schizotypy. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;227:331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wan L, Friedman BH, Boutros NN, Crawford HJ. P50 sensory gating and attentional performance. Int J Psychophysiol. 2008;67:91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Zou LQ, Wang K, Qu C et al. Verbal self-monitoring in individuals with schizotypal personality traits: an exploratory ERP study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;11:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Horan WP, Brown SA, Blanchard JJ. Social anhedonia and schizotypy: the contribution of individual differences in affective traits, stress, and coping. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Grant P. Is schizotypy per se a suitable endophenotype of schizophrenia?—Do not forget to distinguish positive from negative facets. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Cohen AS, Davis TE III. Quality of life across the schizotypy spectrum: findings from a large nonclinical adult sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Brown LA, Cohen AS. Facial emotion recognition in schizotypy: the role of accuracy and social cognitive bias. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16:474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Schaefer J, Giangrande E, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Aichert DS, Wöstmann NM, Costa A et al. Associations between trait impulsivity and prepotent response inhibition. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34:1016–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Carhart-Harris RL, Brugger S, Nutt DJ, Stone JM. Psychiatry’s next top model: cause for a re-think on drug models of psychosis and other psychiatric disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374: 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.