Abstract

PURPOSE:

The activities of a coordinating center pharmacy (CCP) supporting a multicenter, international clinical trial are described.

SUMMARY:

Serving in a research support role comparable to that of a commercial clinical trial supply company, a CCP within the Johns Hopkins Hospital Investigational Drug Service (JHH IDS) uses its management expertise and infrastructure to support multicenter trials, such as the recently completed Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage, Phase III (CLEAR III) trial. The role of the CCP staff in supporting the CLEAR III trial was overall investigational product (IP) management through coordination of IP-related operations to ensure high-quality care for study participants at study sites in the United States and abroad. For the CLEAR III trial, the CCP coordinated IP supply activities; provided education to site pharmacists; developed study-specific documents, including pharmacy manuals; communicated with trial stakeholders, including third-party IP distributors; monitored treatment assignments; and performed quality assurance monitoring to ensure compliance with institutional, state, federal, and international regulations regarding IP procurement and storage. Acting as a CCP for a multicenter international study poses a number of operational challenges while providing opportunities for the CCP to contribute to research of global importance and enrich the skill sets of its personnel.

CONCLUSION:

The development and implementation of the CCP at JHH IDS for the CLEAR III trial included several responsibilities, such as IP supply management, communication, and database, regulatory, and finance management.

Introduction

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the definition of a clinical coordinating center (CCC) is a group organized to coordinate the clinical aspects of a multicenter trial. Most often, a CCC is headed by the clinical Principal Investigator (PI) who is responsible for protocol development, clinical sites, general oversight of clinical study operations, overall data management, quality assurance monitoring, and communication among all the sites.1,2

The role of the CCP, when engaged with a CCC PI, is overall IP management and protocol compliance by coordinating drug-related operations, procedures, and activities to support investigators and ensure high-quality pharmaceutical care in clinical studies.

The purpose of this article is to help pharmacists understand the roles, processes, advantages, and challenges of the coordinating center pharmacy (CCP) in support of multicenter, international clinical research, as implemented by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Investigational Drug Service (JHH IDS) for the multicenter, international CLEAR III (Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage, Phase III) trial.

CLEAR III Trial

CLEAR III was a multicenter, international, double-blind, randomized study comparing the use of extraventricular drainage (EVD) combined with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) against EVD combined with placebo (normal saline) for the treatment of Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00784134). CLEAR III was supported by a grant from the NINDS, a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), with additional investigational product (IP) support from Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA). Over 90 international major hospitals and academic medical institutions across the U.S., Canada, United Kingdom, Germany, Hungary, Brazil, Spain, Switzerland, and Israel participated as clinical sites. The recruitment phase started September 2009 and ended January 2015.

Clinical Coordinating Center (CCC)

The Division of Brain Injury Outcomes (BIOS) in the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) School of Medicine is an academic research organization (ARO) that served as the CLEAR III Clinical Trial CCC (www.BrainInjuryOutcomes.com). Since 1999, BIOS has coordinated federally-funded and industry-sponsored trials on an international scale across a wide range of neurologic conditions. BIOS utilizes internal pharmacy, pathology, and radiology support services, collaborates with international IP distributors, commercial research organizations, software developers, and holds materials agreements with pharmaceutical companies for the conduct of clinical trials. The CCC team of 15 managers and staff has developed a consortium of nearly 100 international, clinical sites, many of which have participated in multiple trials for more than a decade.

CCP: Johns Hopkins Hospital Investigational Drug Service (JHH IDS)

The Johns Hopkins CCP is a part of the IDS, a division of the JHH Department of Pharmacy. The IDS was established in 1984 to support inpatient and outpatient clinical research conducted by investigators of the hospital and the JHU School of Public Health. The JHH IDS operates out of two distinct locations which separates oncology and non-oncology operations. Hours of operation are Monday through Friday, 7:30 AM to 5:30 PM. An IDS pharmacist is available 24/7 by phone or pager to address issues after hours. The total staff consists of 11 full time equivalent (FTE) pharmacists and four FTE certified pharmacy technicians. Staff are managing approximately 550 clinical drug protocols. In addition to study-specific training, staff are required to complete training in basic human research, research compliance, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the Department of Transportation (DOT) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA) training.

To support the CCP role, two pharmacists were actively involved with the CLEAR III study. However, additional IDS staff provided support for shipping of investigational product, quality assurance documentation checks and communication with site pharmacists. The JHH also served as a CLEAR III site, therefore, staff received training on study procedures and had extensive knowledge of the protocol.

The Roles of the CCP

The JHH IDS, as a CCP, had the following major responsibilities over the course of the CLEAR III trial:

IP supply management

Education and training

Communications

Database management, randomization and blinding

Risk-based centralized site monitoring

Regulatory management

Finance management

IP Supply Management

A CCP should have a detailed IP supply system to efficiently manage IP for multicenter trials. To ensure that sufficient IP is available at depots (CCP or in-country IP distributors) and participating sites during the conduct of a study, the CCP needs to consider site supply and demand forecasting, supply planning with the IP company, lead times for IP shipment from the IP company to the depot and from the depot to the site, lead time for material purchase, storage space at each depot and coordination among the multiple stakeholders. IP supply can become a costly critical path bottleneck in the operation of a clinical trial, if a shortage or interruption of IP occurs. The CCP should build a plan for traceability and documentation of IP from manufacturer to dispensation and destruction, in other words, throughout the entire life of a trial.

IP Packaging and Labelling

The IP for the CLEAR III trial was alteplase sterile powder for reconstitution. Alteplase was commercially available and provided for the trial by Genentech, Inc. For the North American sites, it was repackaged by the manufacturer in a carton containing 6 vials of alteplase 2mg/mL vial. Repackaging to differentiate IP from the commercially available product reduces the risk of using commercial drug inadvertently.

The IP was labeled in compliance with FDA regulations for investigational drugs, in accordance with the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 21 §312.6, Labeling of an investigational new drug. It requires that the label include the specific statement that the product is limited to investigational use only and cannot include statements that are false or misleading or represent that the investigational drug is safe or effective for the purposes for which it is being investigated.3

Each box and vial of alteplase was labeled by the manufacturer, indicating the drug name, drug strength, quantity, lot number, expiration date, storage recommendations and the statement “Caution: New Drug--Limited by Federal (or United States) law to investigational use.”3 The CCP added the kit number, site number and name, and the trial name to make the IP more distinguishable from the commercial supply. The kit number was used only for tracking purposes.

For the European Union (EU) sites, labelling complied with the requirements in article 14 of the Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC and article 15 of good manufacturing practice (GMP) Commission Directive 2003/94/EC. 4,5 The detailed provisions are given in Annex 13 of the EU Guide to GMP.6 Mawdsleys Clinical Trial Services (Salford, UK) created specific labels for vials, which included the trial’s EudraCT (European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials) number, drug name, strength, form, protocol number, kit number and expiry date. The CCP was actively involved in the design and authorization of the CLEAR III label in five languages.

IP Shipment

Initial shipment was triggered by a notification from the CCC to the CCP that the site had completed its site initiation and approval activities, including contracts, site trainings, IRB approval, and all other regulatory documentation. Local study coordinators and pharmacists entered pharmacist contact and shipping information into VISION™ (Prelude Dynamics, Austin, Texas), the CLEAR III trial’s FDA-compliant electronic Trial Master File (eTMF) and electronic data capture (EDC) system during site initiation. This allowed easy organization and maintenance of pharmacy information for both CCC and CCP documentation and tracking.

For North American sites, the CCP sent IP directly to each study site. IP shipments were limited from Monday to Thursday to prevent transit or receipt of IP during the weekend days. Next day delivery was made available in most regions within the U.S. For subsequent shipments, maintaining the blinded study design and sending the replacement shipment in a timely manner to provide continuous and uninterrupted supply was key. Since the CCC staff was blinded to assignment, only the CCP pharmacist received an e-mail message of the randomization assignments within the VISION™ system. If randomized to alteplase, the site pharmacist was contacted to check the inventory status; if the site needed IP, replacement was shipped to the site. A sufficient amount of IP for two subjects was sent at one time. By using smaller distributions and more frequent replenishments to the sites, wastage in clinical supplies and storage burden were minimized.7

Packing slips used as shipping documentation were generated in Vestigo® (McCreadie Group, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI), an electronic investigational drug database management system. The CCP packaged IP in shipping containers designed to maintain the proper storage conditions during shipment. The selection of shipping containers was discussed with the IP manufacturer to assure compliance with specific shipping and storage conditions. In terms of packing the shipping container, adherence to the manufacturer’s directions was essential to reduce the risk of temperature excursion during transit. For international shipments, temperature monitoring devices were enclosed in each shipment.

Upon arrival at the site, the designated study personnel were directed to verify that the contents of the shipment matched the description on the packing list and to confirm that the IP storage conditions had been maintained and was received in good condition. The site pharmacy staff signed and dated the shipping document and communicated any shipping concerns on the receipt packing slip. A copy of the packing slip was sent electronically to the CCP pharmacist. The CCP pharmacist then filed the receipt record in the site study file.

Choosing the right in-country or third-party IP distributor is often more complicated than it appears. The third party IP distributor can influence quality, security and supply integrity to the clinical trial. For international sites, the CCP closely works with the in-country IP distributor. The CCP provides oversight and support for setting up the IP supply chain. The in-country IP distributor may coordinate and handle study IP importation, customs release and IP storage as a country depot, country specific labeling of kits, and distribution to clinical sites.

Storage and distribution of IP to the EU centers was managed by the IP distributer, Mawdsleys. To comply with the Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC, investigator-sponsors conducting clinical trials in the EU require Qualified Person (QP) services to release the IP into the EU.4 For CLEAR III, the QP services included certification of the alteplase GMP compliance, relabeling in multiple languages, distribution to the sites in the EU, and temperature monitoring. The CCP shipped IP to Mawdsleys; Mawdsleys provided cold-chain storage, initial shipping, and replacement shipments on request from the CCP. The CCP retained control centrally by providing notifications and approvals to send IP to sites. All stock was distributed in temperature-validated containers including refrigerant packs with appropriate temperature monitoring.

Temperature Excursion Procedure

Temperature monitoring of IP is important to assure the stability, safety, quality and efficacy of the IP. As mentioned above, drugs must be stored and transported according to the manufacturer’s recommended temperature conditions, as defined in the approved labelling and supported by stability data.8 Table 1 lists the relevant regulations or guidelines for temperature monitoring of IP.9–16

Table 1.

Relevant regulations or guidelines for temperature monitoring of IP

| FDA CFR Title 21 312.23 IND content and format 9 FDA Guidance for Industry E6 Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance 10 FDA Guidance for Industry Investigational New Drug Applications Prepared and Submitted by Sponsor-Investigators11 |

| International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients12 |

| The Joint Commission Standard MM.03.01.0116 |

The CCP should ensure that written procedures include instructions that the investigator or institution should follow for the handling and storage of IP for the trial and documentation thereof. 17 Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for temperature excursions are then written in advance. For CLEAR III, written instructions were developed, as described below. The IP for CLEAR III was transported and stored refrigerated at 2–8°C. All temperature excursions that occurred during transport or at the sites were reported directly to the CCP by either the site pharmacist or the distributor. The CCP transmitted the excursion information to Genentech, using the Genentech temperature excursion reporting form for review and determination of IP disposition. While Genentech analyzed the excursion, the site pharmacist was instructed to quarantine the IP. The CCP instructed the CCC to place the site “on-hold” and to notify the site PI and study team that enrollments were temporarily suspended until the Genentech team replied with their recommendation.

If the IP was deemed usable by Genentech, the site was re-activated by the CCC and the site PI and study team were notified. IP was removed from quarantine and designated as inventory for the trial. If the Genentech review indicated the IP was not for use, a new IP replacement shipment was sent to the site. The site pharmacy was instructed to document and destroy the excursed IP inventory on-site.

Education and Training

Education and training are essential to the conduct of a study and required for study-wide quality assurance activities.18 Special efforts are required in multi-center trials to standardize pharmacy procedures.19

Prior to the site activation, the CLEAR III site pharmacist was required to complete protocol-specific pharmacist training. Pharmacist training was conducted initially by webinar, to allow interactive educational sessions. A pharmacist training module was also placed on the study website as an on-demand refresher with a quiz and a certificate issued to those who completed the course successfully. At times of modification of IP preparation or an IP-related procedure, either a webinar was offered to the site pharmacists and/or the revised training module was distributed directly to all site pharmacists and PIs. Individual phone training sessions were offered to the sites on demand. In addition to pharmacist training, the CCP presented IP preparation and the investigator’s responsibilities at the in-person investigator start-up meeting.

Pharmacy Manual

A trial Manual of Operations and Procedures (MOP) is necessary to facilitate consistency in protocol implementation and data collection across study participants and clinical sites. Having a MOP provides reassurance, to all participants, that scientific integrity and study participant safety are closely monitored and increases the likelihood that the results of the study will be scientifically credible.1

For the CLEAR III study, the pharmacy manual was incorporated as one chapter of the trial’s MOP to assure that uniform pharmacy procedures would be followed across all sites.

The CCP developed, disseminated and updated the pharmacy manual. The pharmacy manual contained detailed, written instructions governing pharmacy operations for conducting the CLEAR III study. It described the local requirements of IP storage, receipt, accountability, record keeping, randomization, dose preparation, syringe labeling, dispensing and final disposition of IPs. The pharmacy manual provided precise instructions concerning what must be put on the label of final IP syringes to prevent accidental unblinding of the IP.

The pharmacy manual also provided samples of the standardized documentation forms, including the enrollment log, IP accountability log and subject specific log to be modified by local pharmacy staff as needed. The IP accountability log should include dates, quantities, batch/serial numbers, expiration dates (if applicable), and the unique code numbers assigned to the IPs and trial subjects.20

Over the course of the five-year study, the pharmacy manual was revised to reflect relevant protocol amendments and to account for changes in pharmacy procedures. The pharmacist training module was revised accordingly to reflect the update of the manual. The revised training module and manual were distributed to all site pharmacists and PI. Also, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) were circulated to each site pharmacist to assist with the understanding of important changes in procedures.

Communications

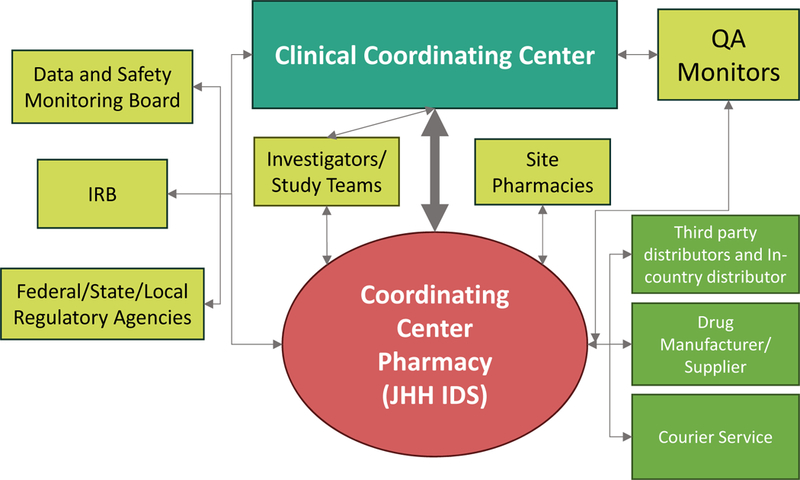

A typical multicenter trial involves multiple clinical centers, a data center, several committees, and other stakeholders.21 In addition to the obvious communications with the enrolling sites and site pharmacists, close CCP integration and communication among suppliers, distributors and couriers are important for implementation and seamless management. Figure 1 shows the CCP interactions with the various CLEAR III stakeholders. The CCP worked in tandem with the CCC/sponsor (CLEAR III was an investigator-initiated, NIH-funded trial) when communicating with the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Institutional Review Board (JHMIRB), and other regulatory agencies. The CCP played a significant, independent role with the CLEAR III Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), being responsible for providing blinded grouped data and temperature excursion safety data for DSMB review. The CCP pharmacists independently monitored site documents, and managed directory information in the eTMF. Regularly, the CCP independently communicated with site pharmacists, third party distributors, the IP manufacturer and courier services both as a service to the sites and to maintain blinding to treatment assignments.

Figure 1.

Schema of Coordinating Center Pharmacy, showing the interactions among relevant parties

The CCP should have SOPs to manage the supply chain from manufacturer shipment to destruction of IP at the end of the trial or at interim IP expiration points, whichever comes first.22 SOPs are also helpful to communicate and resolve unanticipated issues such as protocol deviations, IP- or procedure-related changes, and other concerns of non-compliance. There also needs to be an agreed-upon process for notifying the CCC of personnel changes at the site pharmacies and training the new personnel accordingly.

Database Management, Randomization and Blinding

CLEAR III was a double-blind randomized trial, meaning that, during the course of the trial, neither the local care team nor the patient knew the treatment assignment. In addition, the CCC staff were also blinded to which patients received the randomly-assigned study drug versus a matched placebo. CCP and site pharmacists were unblinded. Maintaining blinding in a large international surgical trial presented numerous challenges.

Chief among them was the randomization process itself. Prior hemorrhagic stroke studies have shown that certain factors, such as the size (volume of blood) and location of intracerebral hemorrhage, impact the likelihood of a positive outcome for the patient. CLEAR III used a covariate-adaptive randomization algorithm whereby these factors were considered at the time of randomization to ensure overall balance across these important factors (covariates) between the treated and medical control groups. Adaptive randomization improves the power of a study to statistically distinguish a treatment effect, but it also means that randomization schedules cannot be predefined.23,24 With CLEAR III being a somewhat emergent trial, the adaptive randomization was designed to function 24 hours a day and to work across country and language boundaries.

When the local site investigator had collected and entered the required baseline data and was ready to randomize a patient into the trial, the VISION™ electronic data collection (EDC) system ran the adaptive randomization algorithm to determine the treatment assignment. To maintain the blinding, the EDC system confidentially sent the treatment assignment directly to the local site pharmacist, either via email or facsimile transmission. Following transmission of the assignment, the local pharmacist then prepared the IP without disclosing the treatment assignment to the patient care team or CCC staff. This enabled investigators to administer study drug to subjects in a manner that blinds investigators and subjects.

Should the treatment assignment blind need to be broken in an emergency or should transmission to the site fail, the randomization notice was also sent to the CCP, as a backup to the local pharmacist. This information was also used by the CCP to monitor IP inventory at the site, so that additional supplies could be sent to the site without having to risk unblinding the CCC team or the local site team by involving them in IP supply issues.25

Risk-based Centralized Site Monitoring

In August 2013, the FDA published a draft guidance recommending risk-based approaches to monitoring.17 The CCC partnered with a commercial contract research organization (CRO), Emissary International, LLC (www.Emissary.com), to provide independent data monitoring and quality assurance support. A commercial-academic collaboration can add expertise and capabilities not typically used in traditional academic trials, including high-powered EDC systems and cost-saving, quality-improving approaches such as centralized monitoring. The CLEAR III trial followed this approach and conducted most monitoring centrally. This approach places a greater responsibility on the CCP to train and manage the local pharmacists remotely as well.

The CCP conducted centralized monitoring for IP related documentations, including site inventory, tracking of expiration dates and temperature excursions, and IP destruction. Communication between the CCP and the site pharmacists was an essential component of monitoring. Ongoing communication of IP inventory and temperature monitoring occurred throughout the trial. IP accountability logs were requested at the time of IP destruction.

At various times of the study, IP had to be destroyed because of expiration dates or it was deemed unusable due to temperature excursions. IP expiration dates were tracked by the CCP, and the CCP received communications about all temperature excursions at the sites or the third party depot. The CCP reviewed each site’s institutional IP destruction SOP and IP destruction documentation when the IP expired or was deemed unusable. During site close-out, the CCP required the site pharmacies to submit their local SOPs for the destruction of pharmaceuticals and/or pharmacy waste, documentation of study IP destruction, a copy of the IP accountability log(s), and a copy of the refrigerator temperature logs for the time period that IP was stored at the site. For CLEAR III, the decision for on-site IP destruction was first approved by the manufacturer as the provider of the IP for the trial and in accordance with a signed, pretrial materials agreement.

Regulatory Management

The CLEAR III trial was conducted in accordance with the regulations published in the Code of Federal Regulations 21 CFR 312. These regulations define the procedures and requirements governing the use of investigational new drugs and with GCP requirements as recommended by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH E6). The management of IP is one of the critical tasks that should be documented in compliance with GCP, including shipment of drugs to the many investigational sites in the United States and different countries and how they are managed at the enrolling sites.26 To this end, the CLEAR-III trial used the VISION™ eTMF as the master repository and document manager for all site and sponsor regulatory documentation. The CCC defined standard source documents for patients, sites, and personnel and the documents were uploaded to create electronic study binders with limited access by user role.

The CLEAR III trial included regulatory activities with the IRBs, as well as the FDA, NIH, State Department, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and manufacturers. The pharmacy procedures additionally included regulatory activities with USP Chapter <797> pharmaceutical sterile compounding regulations and Joint Commission standard.16

For the non-U.S. sites, the regulatory requirements were expanded to include foreign ethics committees, competent authorities, such as Health Canada, Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM), and other European Union agencies. For the international sites, it was important to work with the in-country distributors regarding country-specific regulations for import, such as import permits or licenses and special packaging and labeling requirements.27 For example, for shipping to Israel, the approval for import first had to be obtained, the package label of the IPs had be written in Hebrew, and there had to be certification of non-dangerous goods (non-hazardous) for enclosed temperature monitoring devices. The CCP collected and maintained documentations for imports and exports – documentation of invoices and receipt record of the sites, documentation of IP-related certificates from the manufacturer, documentation of temperature excursion report and review, randomization report, IP destruction records and site IP destruction policies.

In addition, for the CCP, there is an EU requirement for sample retention. Reference and retention samples of investigational medicinal product, including blinded product are retained either until the analyses of the trial data are completed or as required by the applicable regulatory requirement(s), whichever period is longer.

The CCP is responsible for maintaining adequate records showing receipt, shipment, or other disposition of IP. The FDA requires the investigators to retain records for 2 years after a marketing application is approved or after the investigation is discontinued and the FDA is notified.28 ICH E6 guidance requires the sponsor to retain the sponsor-specific essential documents until at least 2 years after the last approval of a marketing application in an ICH region and until there are no pending or contemplated marketing applications in an ICH region or at least 2 years have elapsed since the formal discontinuation of clinical development of the investigational product.10

Finance Management

The CCP prepares the pharmacy budget that is submitted to the CCC to cover the pharmacy cost for support for a trial. To forecast the pharmacy budget, factors that need to be considered are the number of sites, the number of subjects to be enrolled, expectations of the pharmacy requirements to support the trial, duration of the trial, determination of space requirements, IP storage recommendations, and the determination of the number of FTEs required.

The itemized pharmacy budget for CLEAR III included administrative, IP inventory management, education and training, and centralized monitoring costs. The administrative costs were for protocol review and development of dispensing procedures, management of protocol amendments, meeting with sponsor, maintaining documents for each site, communication with site pharmacists and study team members, regulatory requirements and DSMB reporting. IP inventory management costs included IP storage, monthly inventory, expiration tracking, temperature monitoring, supply costs, IP packaging and shipping and IP destruction tracking. Education and training costs included the development of training materials, pharmacy manuals, tracking of staff that have completed training, re-education due to protocol changes and hiring of new pharmacy study members. Centralized monitoring and study close out costs include inventory management, tracking of expiration dates, and tracking of temperature excursion in transit and in situ.

As for billing the CCC, it is important to keep any unblinding information from the team. For example, shipment costs (e.g., IP FedEx fees, placebo was supplied locally with no shipments required) were consolidated and billed quarterly to the CCC.

Discussion

Traditionally, NIH-supported, multicenter trials have been investigator-initiated, employing a new staff and unique infrastructure for each project. In many of the larger academic and/or nonprofit institutions, AROs are emerging with faculty members as CCC investigators, offering a new environment where the ARO provides centralized leadership for running trials.29 Examples of AROs include Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI), Cleveland Clinic Cardiovascular Coordinating Center (C5) Research, the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group, and the BIOS Center at JHU. As opposed to commercial CROs that typically provide operational services for pharmaceutical companies, the primary focus of an ARO is to provide recruitment, retention, statistical leadership, and data management for non-industry funded trials. Another difference between the ARO and the CRO is the greater emphasis on collaboration among multiple AROs, which is less typical among often-competing CROs.30

The CCP has ARO characteristics specific to IP management. Often, IP for multicenter studies is distributed to the sites by a commercial management service with expertise in the handling of drugs.18 Examples of these companies include Almac, Fisher Clinical Services, Parexel-Catalent, etc. These companies work closely with CROs and the pharmaceutical companies. Like the growth of AROs, the CCP in the academic institution has the opportunity to replace commercial clinical trial suppliers for IP management.

For example, CCPs in academic institutions have experience and expertise to manage the IP through their long-standing research experience and support and collaboration with the IRB and other institutional departments. This capability to interface with clinical sites and to understand their operations and challenges is an advantage. In addition, having the CCP and the CCC in the same institution and having a close academic collaboration allows the sharing of a common culture and goals: high research quality and ethics. This assists communication and integration between the CCC, the CCP and the sites. For the CCC, the opportunity exists to include the CCP early in the design of the trial, the MOP and SOPs, the electronic systems, the international legal requirements, the choice of suppliers, budgeting, and the workflow of IP from start to finish. Closely sharing the trial tasks of improving medical knowledge and clinical care can benefit the trial, the CCC and the CCP.

In the era of a declining NIH budget and research funding cuts for sponsor-investigators, the CCP in the academic medical institution can provide competitive IP management service with lower relative costs than commercial clinical supply management companies.28 Also, even at a far lesser charge, running investigator-sponsor trials can have a positive financial impact for CC pharmacies.

Acting as a CCP for a multicenter, international clinical trial can introduce a number of challenges: long learning curves to understand international laws and regulations, extended working hours, troubleshooting concerns or delays of domestic and international shipments, communicating with foreign regulatory agencies and pharmacists, communicating protocol changes to sites, maintaining the blinding of the study IP, and language barriers with international pharmacy personnel, to name a few.

The local IDS pharmacy traditionally has limited experience and knowledge with global requirements and distribution, compared to the commercial clinical trial supply service companies. Participation in a CCP role to support international sites introduces an educational opportunity for global regulation and requirements regarding the conduct of research and distribution of clinical trials material. Furthermore, no systematic training currently exists to develop the roles of CCP pharmacist other than on the job training or previous experiences. For the CLEAR III trial, the CCP had to ship IP to multiple third-party IP distributors. Lack of experience and the practices of the international site pharmacies were challenges to maintain IP integrity and availability to patients respectively.

A key challenge was to have an effective plan for forecasting IP demand. Our CCP closely worked with the CCC to forecast enrollment rates and plan replacement of expiring IP seamlessly and without losing an enrollment due to lack of IP supply. Together we communicated with the manufacturer the expected IP needs to assure sufficient supply of the IP. Independently, monitoring was conducted on each site’s inventory level based on shipment history and randomization result. On the other hand, commercial clinical trial supply companies have knowledge and resources to optimize the supply chain process. Supply chain optimization is now a major research theme in process operations and management.30 One of them is a simulation-optimization computational framework to determine the appropriate level of pooled safety stock levels.31 Commercial clinical trial supply companies use these kinds of techniques to optimize supply chain.

Pharmacy services to support CCC activities create expanded responsibilities for the management of the IP. The CCP requires sufficient resources including staff and project management skills to urgently address the challenges to conduct the clinical trial. This also impacts the need for physical space within the pharmacy and staff to support distribution and management of the IP supply. It is important to review the capabilities and capacity of the CCP to store the IP and shipping materials and process the shipment before the project begins. Physical space was a major challenge for the JHH IDS due to the additional space requirements for documentation storage, IP storage at refrigerated temperature, and storage of shipping supplies. For example, the shipping containers used for international shipments measured 28 × 26 × 28 and weighed approximately 40 pounds. Alternative storage locations were needed to store the shipping containers and the packing materials.

Therefore, expanding the IDS to serve as a CCP requires the institutional support for systematic efforts. Furthermore, it requires an understanding of the state, federal, and international regulations and the required resources, including substantial planning and implementation time, skills and experiences, and the space for IP storage and packing activities. It is essential for the pharmacist in collaboration with the CCC, investigators, site pharmacists, and vendors, to incorporate this value-added service to the IDS and contribute to continuous improvement in operations to support research and to protect human subjects.

Conclusion

The local IDS pharmacy acting as a CCP for a multicenter, international study brings different aspects of operational opportunities and challenges. The CCP for CLEAR III coordinated IP supply activities, provided education to site pharmacists, and developed study-specific documents, ensuring compliance with institutional, state, federal and in this case international regulations regarding IP storage and procurement.

The development and implementation of the CCP role for CLEAR III held several opportunities for the JHH IDS to contribute to international research operations and resulted in an expanded responsibility for the management of IP and extensive learning experiences. It was rewarding to collaborate with pharmacists, investigators and study teams nationally and globally to conduct research.

Acknowledgement

We thank the patients and families who volunteered for this study and Genentech Inc. for the donation of investigational product. Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage Phase III (CLEAR III) is supported by the grant 5U01 NS062851–05 awarded to Dr. Daniel Hanley from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

Contributor Information

Jihyun Esther Jeon, Department of Pharmacy, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD..

Janet Mighty, Department of Pharmacy, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD..

Karen Lane, Division of Brain Injury Outcomes, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD..

Nichol McBee, Division of Brain Injury Outcomes, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD..

Ryan Majkowski, Division of Brain Injury Outcomes, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD..

Steven Mayo, Emissary International LLC, Austin, TX..

Daniel F. Hanley, Division of Brain Injury Outcomes, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD..

References

- 1.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NINDS Glossary of Clinical Research Terms. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/research/clinical_research/basics/glossary.htm (accessed 2015 August 15)

- 2.Johns Hopkins Medicine. Coordinating Center Functions and Multi-Site Studies. http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/institutional_review_board/guidelines_policies/guidelines/coordinating.html (accessed 2015 August 9)

- 3.Food and Drug Administration. CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. 21CFR312.6 Labeling of an investigational new drug. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=312.6 (accessed 2015 August 9)

- 4.European Commission. Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC. http://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/clinical-trials/directive/index_en.htm (accessed 2015 September 16)

- 5.The Commission of the European Communities. Commission Directive 2003/94/EC. Good Manufacturing Practice In Respect of Medicinal Products for Human Use and Investigational Medicinal Products for Human Use. 2013; Office Journal of the European Union L 262/22

- 6.European Commission. EudraLex The Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the European Union Volume 4 EU Guidelines to Good Manufacturing Practice Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use. Annex 13 Investigational Medicinal Products. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-4/2009_06_annex13.pdf (accessed 2015 September 9)

- 7.Marks RG, Conlon M, Ruberg SJ. Paradigm shifts in clinical trials enabled by information technology. Stat.Med, 2001; 20: 17–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Canada. Guidelines for Temperature Control of Drug Products during Storage and Transportation (GUI-0069) 2011. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/compli-conform/gmp-bpf/docs/gui-0069-eng.php (accessed 2015 April 9)

- 9.Food and Drug Administration. Code of Federal Regulations. 21CFR312.23 IND content and format 2015. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=312.23 (accessed 2015 September 21)

- 10.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry E6 Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm073122.pdf (accessed 2015 Sep 4)

- 11.Food and Drug Administration. Investigational New Drug Applications Prepared and Submitted by Sponsor-Investigators. 2015. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM446695.pdf (accessed 2015 September 21)

- 12.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. 2000. http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Quality/Q7/Step4/Q7_Guideline.pdf (accessed 2015 September 21)

- 13.United States Pharmacopeia. <1079> Good Storage and Distribution Practices for Drug Products. Pharmacopeial Forum. 2015. USP38–NF33; 37(4): 1035 [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Pharmacopeia. <1079> Monitoring Devices - Time, Temperature, and Humidity. Pharmacopeial Forum. 2015. USP38–NF33; 38(3): 1210 [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Pharmacopeia. <1191> Stability Considerations in Dispensing Practices. Pharmacopeial Forum. 2015. USP38–NF33; 28(1): 1381 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Medication management. Sec.1. Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals: the official handbook. Oakbrook Terrace, IL; 2004; MM 1–20 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Oversight of Clinical Investigations — A Risk-Based Approach to Monitoring. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation (accessed 2015 September 9)

- 18.Blumenstein BA, James KE, Lind BK et al. Functions and organization of coordinating centers for multicenter studies. Control Clin Trials. 1995; 4;16 (2, Supplement):4–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meinert CL. Clinical trials: design, conduct, and analysis. 2nd ed New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. 665p. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meinert CL. Organization of multicenter clinical trials. Control Clin Trials, 1981; 1, 4: 305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Harmonised Tripartite. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. 1996. http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdf (accessed 2015 September 18)

- 22.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975; 31: 103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weir CJ, Lees KR. Comparison of stratification and adaptive methods for treatment allocation in an acute stroke clinical trial. Statist Med 2003; 22:705–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman DA Yu R. The other randomization - methods for labeling drug kits. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014; 38, 2: 270–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Méthot J, Brisson D, Gaudet D. On-site management of investigational products and drug delivery systems in conformity with good clinical practices (GCPs). Clinical Trials. 2012; 9(2):265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patricia VA. Managing the Global Clinical-Trial Material Supply Chain. http://www.pharmtech.com/managing-global-clinical-trial-material-supply-chain?id=&sk=&date=&pageID=3 (accessed 2015 Sep 4)

- 27.Food and Drug Administration. CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. 21CFR312.62 Investigator recordkeeping and record retention. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=312.62 (accessed 2015 September 20)

- 28.Shuchman M Commercializing Clinical Trials — Risks and Benefits of the CRO Boom. Journal N Engl J Med. 2007; 357; 14: 1365–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig JR, Rorick TL, Lisa GB, et al. “Chapter 3. The Role of Academic Research Organizations in Clinical Research.” Understanding Clinical Research. Eds. Lopes Renato D, and Harrington Robert A. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah N Pharmaceutical supply chains: key issues and strategies for optimization. Comput.Chem.Eng, 2004; 28, 6–7: 929–941 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y Pekny J.F. Reklaitis G.V. Integrated planning and optimization of clinical trial supply chain system with risk pooling. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research. 2013; 52, 1: 152–165 [Google Scholar]