Abstract

The present study evaluated the combined effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for postnatal depression. A systematic search was conducted across databases including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane library to identify the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that assessing CBT versus control for postnatal depression until March 2017. Data was extracted by two reviewers, independently. The Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 11.0 were used to calculate the synthesized effect of CBT on depression, and anxiety. A total of 20 RCTs involving 3623 participants were included. The results of meta-analysis showed that CBT was associated with a better Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) than control in short-term (mean difference = -2.86, 95% CI: -4.41–-1.31; P<0.05) and long-term (mean difference = -1.68, 95% CI: -1.81–1.56; P<0.05). CBT also improved short-term (mean difference = -6.30, 95% CI: -11.32–-1.28; P<0.05) and long-term (mean difference = -4.31, 95% CI: -6.92–-1.70; P<0.05) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Subgroup analysis based on intervention types showed that in-home and telephone-based therapy exhibited significant reductions in EPDS scores (P<0.05 for all). CBT significantly improved the short-term [odds ratio (OR) = 6.57, 95% CI: 1.84–23.48; P<0.05] and long-term (OR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.61–2.48; P<0.05) depressive symptomatology as compared to control. CBT also reduced the score of Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS), though without significance. In conclusion, CBT effectively improved the symptoms and progression of postnatal depression.

Introduction

Pregnancy is usually accompanied with various psychological conditions such as depression, even after childbirth [1]. As reported by the world health organization (WHO), depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide [2]. Depression is rendered to increase the disease burden in women with respect to all health conditions [3]. Depression negatively affects physical and social functions and is a major risk factor for suicide [4]. Anxiety and depression are the most common symptoms in the complex psychological changes during pregnancy [5–7]. Physical, pathological, and social changes, that leading to anxiety and depression will continue from the prenatal period to puerperium [8, 9]. Thus, the most common female mental disorder, that is postpartum depression, refers to depression occurring during puerperium. Postpartum depression usually occurs 2 weeks after childbirth, and the symptoms are typical at 4–6 weeks [8, 9]. Postnatal depression (PND) is often referred to a condition occurring after childbirth [10]. In most studies, the population of PND includes women with continuous depression from pregnancy to childbirth, as well as women who never experienced depression until childbirth [2, 10]. Previous studies also reported that the prevalence of PND ranged from 13% to 19.2% in new mothers during the first few months after childbirth [11, 12]. The common symptoms of PND include emotional lability, guilt, dysphoria, confusion, and even suicidal tendency [4, 13]. If untreated, severe clinical symptoms will appear and ultimately increase the risk of suicide [4, 13]. Meanwhile, some studies suggested that early diagnosis and intervention of PND are advantageous in relieving the negative impacts on women [3, 14].

A variety of PND treatment options, including a combination of therapies encompassing medication and psychotherapy exist [5]. Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and selective 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) reuptake inhibitors can effectively improve the symptoms of PND. However, the medication therapy may affect the baby via milk metabolism [15, 16]. Thus, clinical attention has been focused on psychological counseling and interventions. A number of published trials have compared the efficacy of different therapies on PND [3, 15, 17]. The psychological therapy can stimulate the inherent maternal motivation, improve the ability to cope with PND without carrying adverse drug reactions to breastfeed infants [18, 19]. Investigators speculated that abnormal emotions and behavior of PND were related to distorted cognition, thereby recommending psychological treatment as the preferred approach for PND [20, 21]. Besides, PND patients prefer psychological therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psychodynamic therapy, interpersonal therapy (IPT), and counseling [2, 19]. Some reviews have shown that these means are effective options for improving PND [2, 22]. CBT is one of the non-pharmacological therapies that has been applied in clinical practive in recent years [19, 23]. Several studies have reported that CBT exerts significant therapeutic effects on PND [2, 8, 11, 23, 24]. Whether CBT and which type of CBT is superior in reducing risk and relieving symptoms of PND is still required to be elucidated.

In this study, we aimed to explore whether CBT was more efficient in improving the depressive condition of women following childbirth as compared to treatment as usual by meta-analysis.

Materials and methods

This study was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (S1 Table).

Search strategy

Databases including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched for identifying randomized controlled trials(RCT) with respect to CBT in women with PND until March 2017. Additional relevant studies were also screened from references of the included studies, conference or meeting abstracts, and registered websites of clinical trials. The keywords and terms such as “puerperal depression”, “postnatal depression”, “postpartum depression”, “puerperium depression”, “cognitive-behavioral”, and “cognitive behavioral therapy” were used in various combinations during the search. The number of selected studies in different databases were recorded in Excel table. No regional and racial restrictions were applied during the search. The primary language of eligible studies was English; however, articles in Chinese or other languages were also considered for inclusion as necessary. The manually searching of target journals was performed to obtain potential eligible studies and the corresponding authors of included studies were contacted if there were missing key data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: Patients: The cohort of patients included women, who gave birth to an infant in the past year, with formal diagnosis of PND or with the risk of PND. Comparison: Each trial was comprised of two groups, one received CBT, and the other received usual care, home visiting, waitlist control, or other conventional treatment. Outcomes: The mean depression score and its associated standard deviation before and after intervention in the control and experimental groups were extracted and recorded[common depression score scale includes Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)] [9, 25]. The improvement rates of PND after treatments were also extracted. Study design: the forms of CBT included internet-based therapy, telephone-based therapy, in-home therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy. Therefore, if the interventions of the included studies belonged to one of the therapies mentioned above, the RCTs would be considered for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria: Observational studies, animal studies, reviews, and other types of non-RCTs were excluded. Articles without sufficient information or data were also discarded after contacting key authors.

Data extraction

The baseline characteristics of patients and target data of outcomes were extracted from eligible studies by two reviewers, independently. These information were about study authors, published year, the number of cases, average age, sex ratio, diagnostic criteria of PND, and baseline history of depression. Primary data were interventions, symptoms of anxiety and depression, improvements rates, different types of depression score scale, diagnostic accuracy statistics, relapse rate of PND. Secondary outcome was the improvement in quality of life. When there was discrepancy about the extracted data, it would be resolved by discussing with the third reviewer.

Quality assessment of included studies

RCTs were included only if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria and the following quality assessment. The quality of included studies was evaluated according to the criteria provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [26]. The quality elements such as selection bias, blinding bias, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting bias, and other bias were assessed. A third reviewer resolved the disagreement in case of controversy. The final quality of each study was defined as high-risk, unclear risk or low-risk of bias, according to the handbook mentioned above.

Statistical analysis

This meta-analysis was conducted using the RevMan 5.3 software provided by the Collaboration Network [26] and the Stata 11.0 software (StataCorp LLC). Data were represented as standardized mean difference (SMD) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) [2]. The chi-squared test (presented as I2) was used to analyze the heterogeneity of the included studies (P<0.1 was set as the test level), and the degree of heterogeneity was judged based on the value of I2. If I2 was >50%, it was considered a high-risk of heterogeneity. Then, the subgroup analysis was introduced to evaluate the clinical homogeneity. If a high-risk of heterogeneity as absent in the analysis, the fixed effect model was used, otherwise, the random-effects model was applied. The sensitivity analysis was conducted when a high-risk of bias was indicated. The odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used to present the dichotomous data. The continuous variables were analyzed in term of mean ± standard deviation. For continuous data, the weighted mean difference (WMD) was used if the measurement unit of continuous variables was identical, or, the standardized mean difference (SMD) was used. Funnel plots and the Egger’s and Begg’s tests were used to assess the publication bias. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant for combined effectiveness assessment.

Results

Literature research

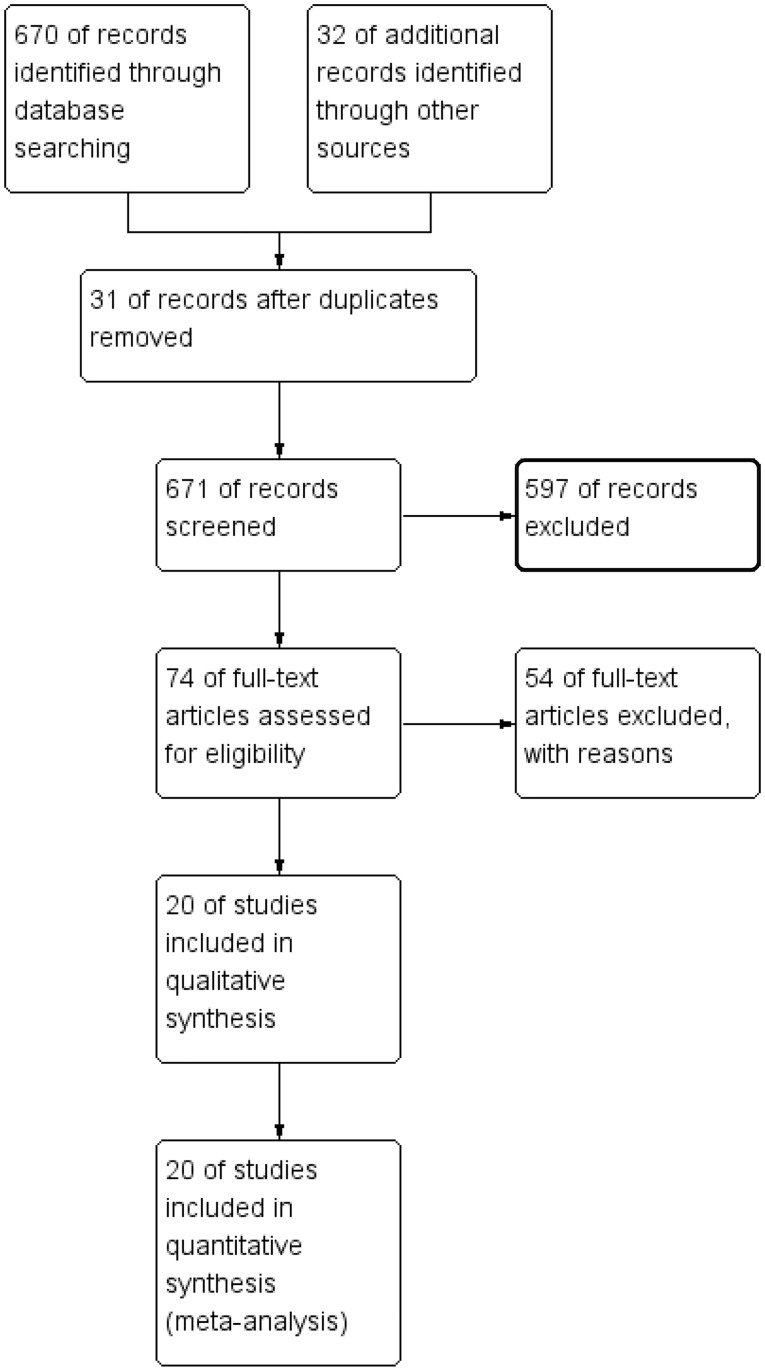

The search results of the RCTs by the two evaluators were highly consistent. According to the search strategy and data collection methods, a total of 702 articles published from 1993–2017 were retrieved. After screening the titles and abstracts, 628 articles were abandoned due to the irrelevant topic or research purposes, animal study, drug treatment, or improper evaluation of efficiencies and outcomes. After further reading the full text, 54 studies were excluded because of non-RCTs, reviews, and reduplication. Finally, 20 studies [15, 20, 21, 27–43] (Fig 1) were included. These studies involved 3623 participants, comprising of 1923 cases in the psychological intervention group and 1700 in the control group. These studies were performed worldwide and published in English.

Fig 1. Schematic of the study selection.

General information and characteristics of included studies

Patients

Among these 3623 participants, 1923 cases were in the intervention group, and the remaining 1700 cases were in the control group. The age of this population ranged from 18 to 37 years. Most of the participants were primiparous and married. The definition and criteria of PND varied among the included studies. EPDS, BDI, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hamilton Rating Scale were used in various studies for defining PND. The baseline characteristics of the eligible studies are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Region | Types of CBT | Int | Con | total number | N in Int | N in Con | Age in Int | Age in Con | Outcomes | measure methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ngai FW | 2017 | China | telephone | CBT | Treatment as usual | 397 | 197 | 200 | 31.1 (3.8) | 30.4 (4.4) | Health related QOL | SF-12 |

| Pugh NE | 2016 | Canada | internet | CBT | Treatment as usual | 47 | 24 | 23 | >18 | >18 | depression, recovery | EPDS, PSI, DASS |

| Leung SS | 2016 | China | group | CBT | Treatment as usual | 164 | 82 | 82 | 31.56(3.78) | 30.9(5.7) | depression, anxiety | EPDS, HADS |

| Dimidjian S | 2016 | USA | mindfulness | CBT | Treatment as usual | 86 | 43 | 43 | 30.98 (4.08) | 28.72 (5.50) | Depressive Symptom Severity | EPDS |

| Milgrom J | 2016 | Australia | internet | CBT | Treatment as usual | 43 | 21 | 22 | 31.7(4.6) | 31.5(4.3) | depression, anxiety | SCID, BDI, DASS |

| Fathi-Ashtiani A | 2015 | Iran | hospital | CBT | Treatment as usual | 135 | 64 | 71 | 25(3.58) | 26(3.82) | depresssion, anxiety | EPDS, BDI, BAI |

| Ngai FW | 2015 | China | telephone | CBT | Treatment as usual | 397 | 197 | 200 | 31.1(3.8) | 30.4(4.4) | depression, recovery | EPDS |

| Milgrom J | 2015 | Australia | group | CBT | Treatment as usual | 45 | 30 | 15 | 30.1 (5.5) | 31.6 (3.2) | depression, anxiety | BDI,BAI,PSI |

| Hou Y | 2014 | China | hospital | CBT | Treatment as usual | 249 | 128 | 121 | 28(3) | 28(4) | depression and sleep quality | EPDS, PSQI |

| O’Mahen HA | 2013 | UK | internet | CBT | Treatment as usual | 910 | 462 | 448 | 32.3 (4.7) | 32.2 (5.7) | depresssion, recovery | EPDS |

| Ammerman RT | 2013 | USA | in-home | CBT | standard home visiting | 93 | 47 | 46 | 22.4 (5.2) | 21.5 (3.9) | psychological distress, social support, and social network | Brief Symptom Inventory |

| Milgrom | 2011 | Australia | group | CBT | General practitioner management | 68 | 22/23 | 23 | 31.5 (4.7) | 31.5 (4.7) | depression, recovery | BDI |

| Morrell | 2009 | UK | in-home | CBT | Treatment as usual | 418 | 271 | 147 | 30.9 (5.4) | 30.9 (5.4) | depression, recovery | EPDS, STAI, SF-12, PSI |

| Austin MP | 2007 | Australia | group | CBT | Treatment as usual | 277 | 191 | 86 | 31.4 | 31.4 | depression, anxiety | EPDS, STAI |

| Milgrom | 2005 | Australia | group | CBT | Treatment as usual | 192 | 46 | 33 | 29.7 (5.4) | 29.7 (5.4) | depression | BDI, BAI, social support |

| Misri S | 2004 | USA | group | CBT | Treatment as usual | 35 | 19 | 16 | 29.52 (5.85) | 30.81 (3.31) | depression, anxiety | HAM-A, HAM-D, EPDS |

| Cooper | 2003 | UK | in-home | CBT | Treatment as usual | 193 | 43 | 52 | 27.7 (5.4) | 27.7 (5.4) | depression, anxiety | EPDS |

| Honey | 2002 | UK | hospital | CBT | Treatment as usual | 45 | 23 | 22 | 27.9 (5.5) | 27.9 (5.5) | Depressive Symptom | EPDS |

| Chabrol H | 2002 | France | in-home | CBT | Treatment as usual | 48 | 18 | 30 | 30.5 (4.3) | 30 (5) | depression, recovery | BDI,EPDS |

| Prendergast | 2001 | USA | group | CBT | Ideal standardized care | 37 | 17 | 20 | 32.2 | 32.2 | depression | EPDS |

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; Int, intervention; Con, control; N, number; QOL, quality of life; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PSI, Parenting Stress Index; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HAM-A, 14-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HAM-D, 21-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Interventions

All studies had intervention and control arms. Among these studies, internet-based therapy, telephone-based therapy, in-home therapy, and mindfulness therapy were used as the intervention for PND patients. These therapies were carried out by psychologists, or trained nurses, or researchers. The duration of treatment ranged from 1 to 12 sessions. On the other hand, traditional treatments such as medication, counseling service, collaborative care, and other forms of therapies were used in the control groups.

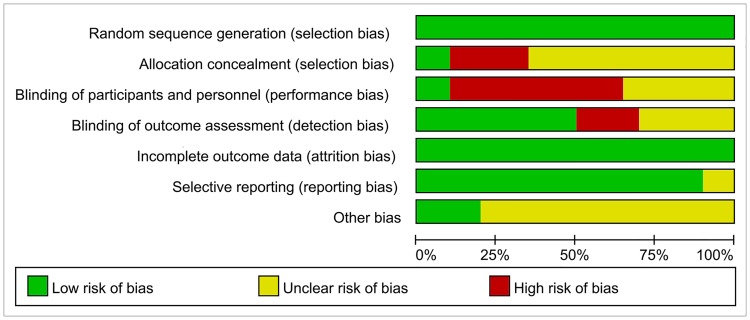

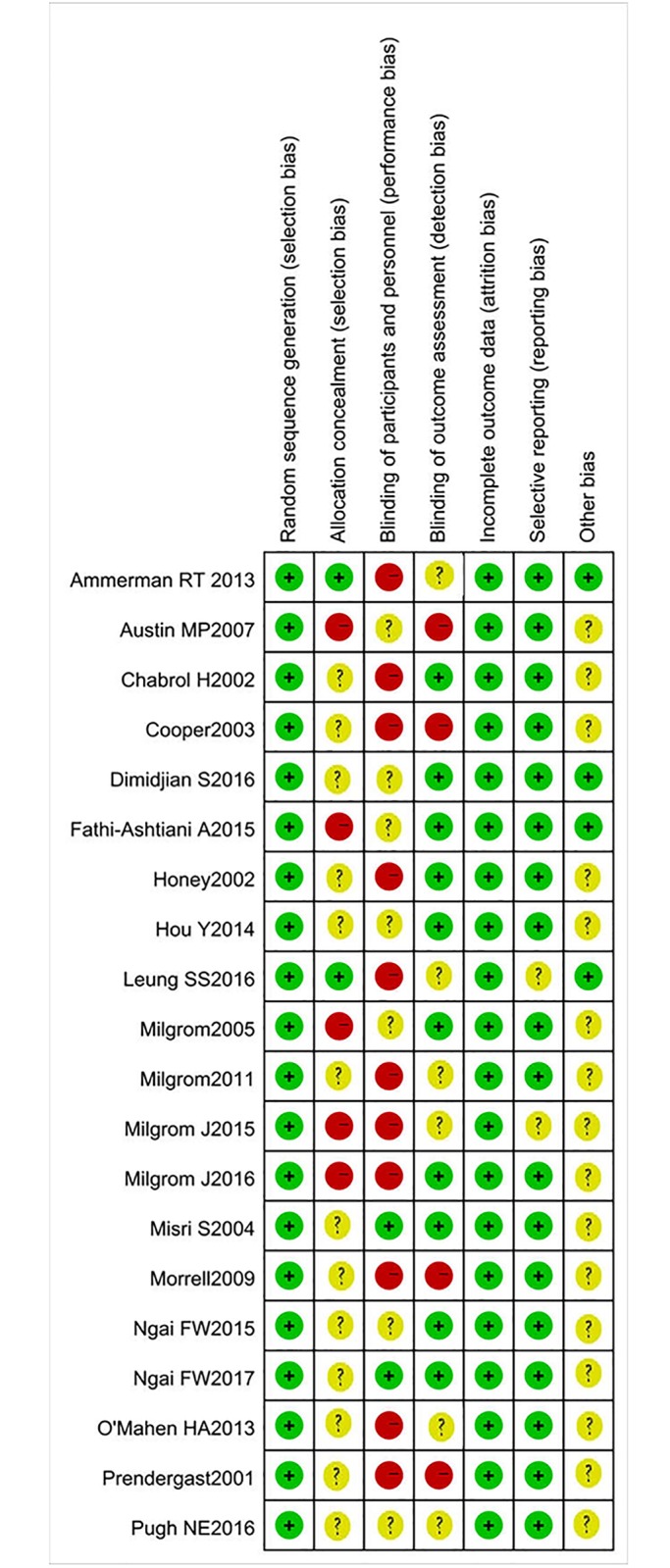

Quality assessment of included studies

Although randomization was reported in all included RCTs, few studies [27, 33, 39, 42] reported specific method of randomization. It was impossible to set blind for patients due to the theory of the intervention, however, some studies [27, 39] reported that blind was applied in the study design. We regarded high-performance bias in these trials. Due to the critical requirements or missing data of the allocation concealment, most of the included studies were considered as high-risk or unclear risk of allocation concealment. Overall, according to the risk assessment criteria of the Cochrane Handbook, more than 60% of the studies were considered as low-risk of bias, approximately 30% as unclear risk, and less than 10% as high-risk of bias (Figs 2 and 3).

Fig 2. Risk of bias graph: A review of the authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Fig 3. Summary of risk of bias: A review of the authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item in each included study.

Effectiveness of interventions

PND symptoms

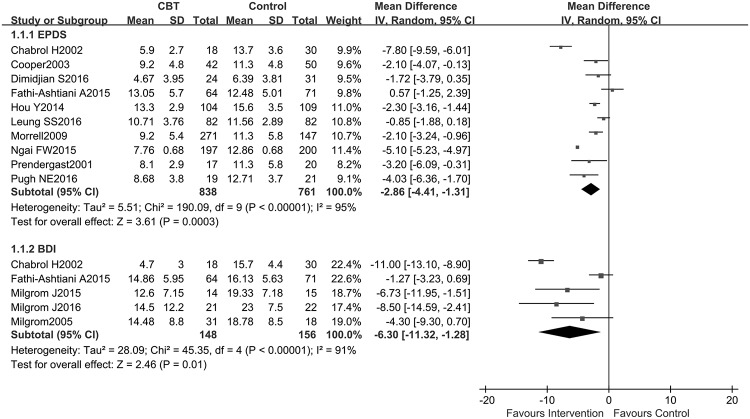

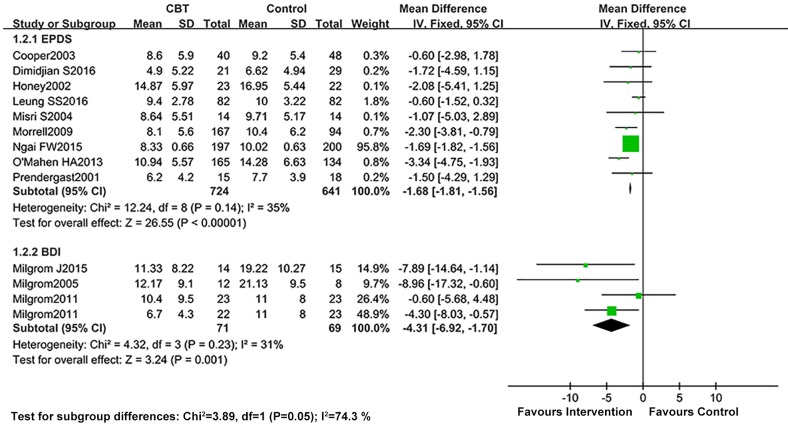

A total of 13 studies reported the data pertaining the improvement of depressive symptoms after interventions as assessed by either EPDS or BDI. Heterogeneity detection results did not suggest a significant heterogeneity (I2<40%) for long-term evaluation, and the fixed effects model was introduced for this part of the meta-analysis. After CBT, the scores of EPDS in the intervention group were significantly lower than those in the control group, and the differences in both short- and long-term effects were statistically significant (short-term: SMD = -2.86, 95% CI: -4.41–-1.31; P<0.05, and long-term: SMD = -1.68, 95% CI: -1.81–-1.56; P<0.05). The results are presented in Figs 4 and 5. While assessing the effect of CBT on short-term of BDI, the random effects model was applied owing to significant heterogeneity (I2>50%). The results of meta-analysis showed that the scores of BDI in the CBT group reduced more than those of the control group, both in short-term (mean difference = -6.30, 95% CI: -11.32–-1.28; P<0.05) and long-term (mean difference = -4.31, 95% CI: -6.92–-1.70; P<0.05). The studies on sensitivity analysis by Ngai et al. [31] and Morrell et al. [36] were the main sources of heterogeneity (S1 Fig). The study of Fathi-Ashtiani et al. [30] was considered as the primary source of heterogeneity for pooled analysis of short-term BDI (S2 Fig). After removing this study, the I2 decreased from 91 to 58%.

Fig 4. Combined results of EPDS and BDI scores comparing CBT vs. control conditions immediately post-intervention: A random effects analysis.

Fig 5. Combined results of EPDS and BDI scores comparing CBT vs. control conditions at long-term post-intervention: A random effects analysis.

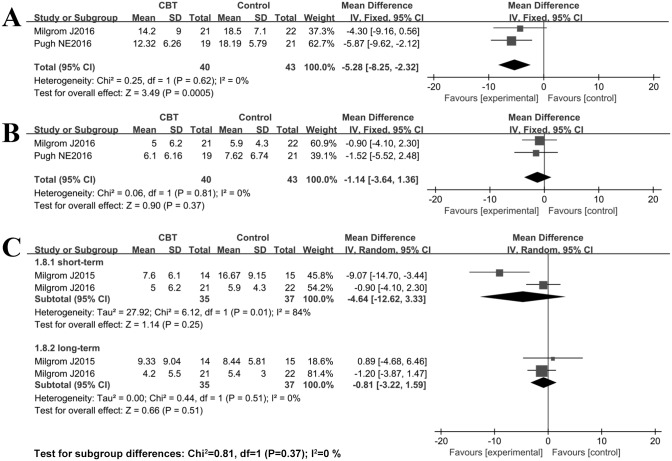

Other indicators of depression and/or anxiety were also evaluated, although only three RCTs reported data regarding BAI and DASS. No significant heterogeneity was observed as indicated by the I2%, and thus, the fixed effects model was used for DASS analysis, but not for BAI (I2>50%). The results of meta-analysis showed that the scores of BAI in the intervention group were lower than those in the control group; however, the differences of short-term (SMD = -4.64, 95% CI: -12.62–3.33; P = 0.25) and long-term (SMD = -0.81, 95% CI: -3.22–1.59; P = 0.51) were not statistically significant. On the other hand, the combined results showed that the scores of DASS in the intervention group were lower than those in the control group, and the difference of DASS-stress (SMD = -5.28, 95% CI: -8.25–-2.32; P<0.01) was statistically significant, except for DASS-anxiety (SMD = -1.14, 95% CI: -3.64–1.36; P = 0.37). The detailed results are illustrated in Fig 6.

Fig 6. Forest plot of DASS and BAI scores comparing CBT vs. control conditions post-intervention: A random effects analysis.

A, DASS-stress; B, DASS-anxiety; C, BAI -anxiety.

Subgroup analysis based on the types of intervention

As several types of therapies were used among these included studies, we performed a subgroup analysis to determine the most optimal intervention that exerted the best effect on relieving symptoms of depression with respect to EPDS. The results showed that in-home-based CBT was significantly superior in improving depression in short-term (SMD = -0.97, 95% CI: -1.81–-0.13; P<0.01) and long-term (SMD = -0.31, 95% CI: -0.57–-0.05; P<0.01) as compared to the control group. Internet-based and telephone-based therapies were also efficient; however, the results were not convincing owing to the limited number of included studies (S3 and S4 Figs).

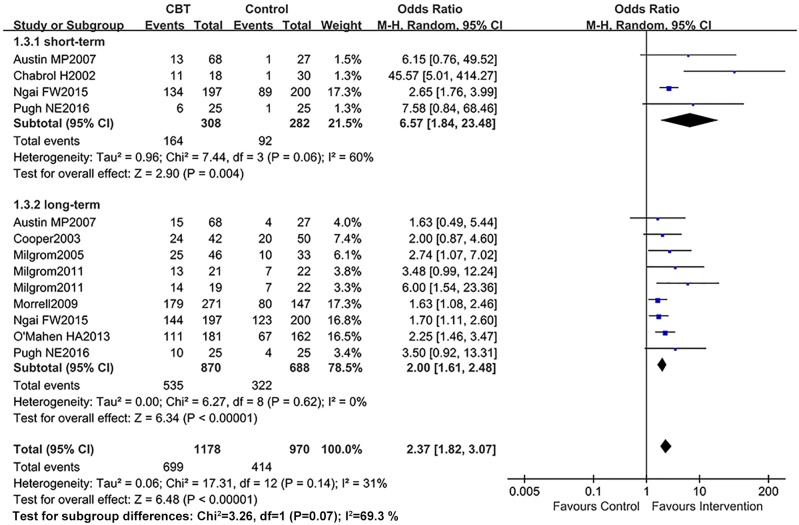

Improvement of postnatal depression after treatments

Ten RCTs reported women under the diagnostic criteria after interventions. As there was significant heterogeneity (I2>50%), the random effects model was introduced during this part of the meta-analysis. As shown in Fig 7, after CBT, the number of women cured of PND in the intervention group was significantly higher than those in the control group, the differences of short-term (OR = 6.57, 95% CI: 1.84–23.48; P<0.05) and long-term (OR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.61–2.48; P<0.05) were both statistically significant.

Fig 7. Meta-analysis of the OR in women who improved and failed to meet the diagnostic criteria (variously defined) comparing CBT with control post-intervention: A random effects analysis.

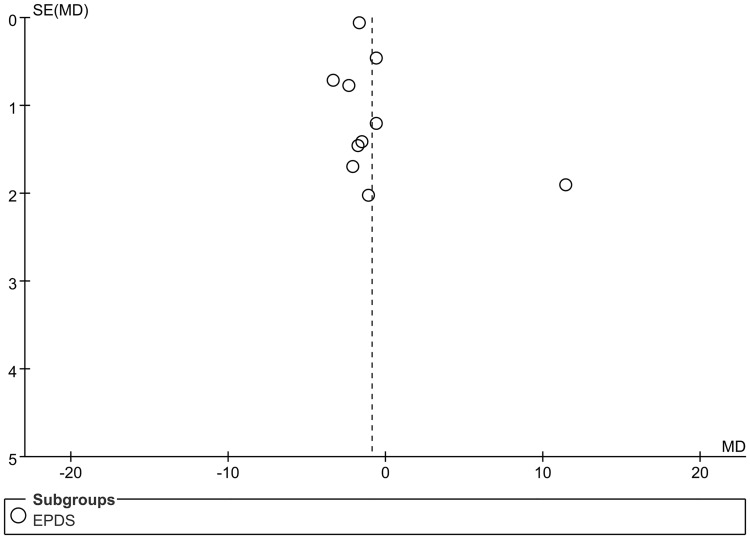

Publication bias

The publication bias of the included studies in EPDS was evaluated using the inverted funnel plots and quantified using the Egger’s test and Begg’s test. Fig 8 demonstrated a satisfactorily symmetrical inverted funnel plot (Egger’s test: P = 0.802>0.05; Begg’s test: P = 0.858>0.05), suggesting no significant bias of publication.

Fig 8. Funnel plots for evaluating the publication bias.

Discussion

Meta-analysis is an important method for evidence-based medicine [26]. It refers to the systematic, objective, and comprehensive quantitative analysis of results from multiple independent studies with identical objectives by appropriate statistical methods. In this study, 20 RCTs were included in the meta-analysis. The results showed that CBT was clinically more effective than conventional therapies, with a reduced number of PND patients and improved symptoms of the disease. Notably, multiple therapies including CBT and anti-depressive medication were used in the included studies, making the effects of therapies difficult to separate from each other.

Recently, several meta-analyses [2, 9, 19, 22] assessed the reliable and effective therapy for PND, and the results were not consistent. In 2013, Scope et al. [44] performed a meta-analysis to evaluate whether CBT could serve as an evidence-based treatment for women with PND as compared to other used packages of care. They identified 7 eligible studies for the final meta-analysis, which showed that the CBT group could be effective in reducing depression when compared with the usual care, routine primary care, or waiting list groups. However, all the included studies were not RCTs, and the varied definitions of the CBT component of the studies suggested that the results should be interpreted cautiously. Morrell et al. [9] systematically evaluated the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of postnatal intervention in women to prevent PND. The meta-analysis designated CBT as the most beneficial intervention. The study concluded that cognitive behavioral therapy was cost-effective with respect to traditional care, although much of the evidence was inconclusive. The present study focused primarily on the cost-efficiency of CBT; the clinical efficiency of the methods has not been assessed systematically. Furthermore, Lau et al. [19] performed another meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of the therapist-supported internet-based CBT on postpartum women. After searching, a total of 8 RCTs involving 1523 participants across six nations were included. They found that this therapy could significantly improve stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in postpartum depressive women as compared to those of the control group. Though the results were positive, the therapist-supported internet-based cognitive behavior therapy was only one specific type of the cognitive behavior therapy. Although these studies determined that CBT was useful in improving the depressive symptoms among women with postnatal depression. However, these meta-analyses did not systematically assess the efficiencies of different types of CBT in treating postpartum women as compared to control groups.

Our meta-analysis found that the CBT, overall or in different forms, had significant benefits in treating women with PND. The overall results of our meta-analysis showed that the CBT exerted good short-term and long-term effects on PND. After the administration of intervention, the symptoms of PND patients could be significantly improved immediately after treatment within few weeks and maintained for >3 months. Non-guided counseling and usual therapy had only a good short-term effect on PND. At the end of the intervention, these methods could significantly improve the symptoms; however, the long-term efficacy was poor. In-home-based, internet-based, and telephone-based exhibited a good short-term effect on PND, and the long-term efficacy remains to be further elucidated. The sub-group analyses showed that the internet-based therapy, telephone-based therapy, in-home therapy, mindfulness therapy, and other forms of CBT were efficacious in relieving symptoms and reducing the number of PND patients. These findings indicated that CBT could exert its therapeutic role in various forms of delivery, enabling the participants to select appropriate therapeutic pathway, thereby increasing the treatment compliance.

This meta-analysis aimed to systematically evaluate the efficiencies of CBT in treating new mothers with PND based on the latest clinical evidence. In the current study, the sub-group analysis was introduced to determine the efficacy of different interventions and forms of therapy delivery. The outcomes of symptoms improvement and short- and long-term effects were also analyzed in our meta-analysis, further strengthening the findings of this meta-analysis. However, there were several limitations within our meta-analysis. First, the number and samples of included RCTs were relatively small, especially in the sub-group analysis. Second, heterogeneity was observed among included studies with respects to study design, treatments, indicators of outcomes, and level of detail of the follow-up. The relapse rate of PND differed between studies. They reported different duration and improvements of depression symptoms. The period of follow-up was different among the included studies, which might over- or under-estimate the actual effectiveness of CBT. Third, the language of eligible studies was primarily limited to English, which might lead to the risk of selection bias. Nevertheless, the results of this meta-analysis showed that CBT was effective in treating PND, both in improving symptoms and reducing the number of patients suffering from the disorder.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the cognitive behavioral therapy is sufficient to relieve the psychological symptoms of postnatal depression and effectively improve the quality of life in new mothers, resulting in a reduced prevalence of postnatal depression. However, our findings are limited due to the uneven quality, the differences in the diagnostic criteria, evaluation methods, and follow-up of the included studies. Thus, rigorous high-quality randomized controlled clinical trials are essential to substantiate the present conclusion.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOC)

Raw data.

(XLSX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are available in the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Verbeek T, Geelhoed-Jenner BNWJ, Nijhuis ER, Peer CD, Berger MY. Psychopathology during and after pregnancy. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 2015; 159(42): [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens S, Ford E, Paudyal P, Smith H. Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions for Postnatal Depression in Primary Care: A Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2016; 14(5): 463–472. 10.1370/afm.1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bais B, Kamperman AM, van der Zwaag MD, Dieleman GC, Harmsen van der Vliet-Torij HW, Bijma HH, et al. Bright light therapy in pregnant women with major depressive disorder: study protocol for a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2016; 16(1): 381 10.1186/s12888-016-1092-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drury SS, Scaramella L, Zeanah CH. The Neurobiological Impact of Postpartum Maternal Depression: Prevention and Intervention Approaches. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2016; 25(2): 179–200. 10.1016/j.chc.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Camps Meschino D, Philipp D, Israel A, Vigod S. Maternal-infant mental health: postpartum group intervention. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016; 19(2): 243–251. 10.1007/s00737-015-0551-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marino C, Riva V, Mornati G, Nobile M, Vanzin L, Dionne G, et al. Paternal postnatal depression affects 6-month-old infants development. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2016; 10 102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salari AA, Fatehi-Gharehlar L, Motayagheni N, Homberg JR. Fluoxetine normalizes the effects of prenatal maternal stress on depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in mouse dams and male offspring. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016; 311 354–367. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.05.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Campbell TS, Giesbrecht GF, Letourneau NL, Carlson LE, Madsen JW, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological distress in pregnancy: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016; 17(1): 498 10.1186/s13063-016-1601-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrell CJ, Sutcliffe P, Booth A, Stevens J, Scope A, Stevenson M, et al. A systematic review, evidence synthesis and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness, the cost-effectiveness, safety and acceptability of interventions to prevent postnatal depression. Health Technol Assess. 2016; 20(37): 1–414. 10.3310/hta20370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon S, Dantas JA. Best practice for community based management of postnatal depression in developing countries: a systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2016; 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usuda K, Nishi D, Makino M, Tachimori H, Matsuoka Y, Sano Y, et al. Prevalence and related factors of common mental disorders during pregnancy in Japan: a cross-sectional study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2016; 10 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wald MF, Muzyk AJ, Clark D. Bipolar Depression: Pregnancy, Postpartum, and Lactation. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2016; 39(1): 57–74. 10.1016/j.psc.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacQueen GM, Frey BN, Ismail Z, Jaworska N, Steiner M, Lieshout RJV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 6. Special populations: Youth, women, and the elderly. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016; 61(9): 588–603. 10.1177/0706743716659276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashmi AM, Bhatia SK, Bhatia SK, Khawaja IS. Insomnia during pregnancy: Diagnosis and rational interventions. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2016; 32(4): 1030–1037. doi: 10.12669/pjms.324.10421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Ericksen J, Burrows G, Buist A, Reece J. Treatment of postnatal depression with cognitive behavioural therapy, sertraline and combination therapy: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015; 49(3): 236–245. 10.1177/0004867414565474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guille C, Newman R, Fryml LD, Lifton CK, Epperson CN. Management of postpartum depression. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2013; 58(6): 632–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuart S, Koleva H. Psychological treatments for perinatal depression. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2014; 28(1): 61–70. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozkurt O, Eras Z, Sari FN, Dizdar EA, Uras N, Canpolat FE, et al. Does maternal psychological distress affect neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants at a gestational age of ≤ 32 weeks. Early Human Development. 2017; 104 27–31. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau Y, Htun TP, Wong SN, Tam WSW, Klainin-Yobas P. Therapist-Supported Internet-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Stress, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms Among Postpartum Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19(4): e138 10.2196/jmir.6712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milgrom J, Danaher BG. Internet Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Women With Postnatal Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial of MumMoodBooster. 2016; 18(3): e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ericksen J, Pugh NE, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Dirkse D. A Randomised Controlled Trial of Therapist-Assisted, Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Women with Maternal Depression. J Med Internet Res. 2016; 11(3): e0149186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lever Taylor B, Cavanagh K, Strauss C. The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016; 11(5): e0155720 10.1371/journal.pone.0155720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yazdanimehr R, Omidi A, Sadat Z, Akbari H. The Effect of Mindfulness-integrated Cognitive Behavior Therapy on Depression and Anxiety among Pregnant Women: a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Caring Sci. 2016; 5(3): 195–204. doi: 10.15171/jcs.2016.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngai FW, Wong PW, Chung KF, Leung KY. The effect of telephone-based cognitive-behavioural therapy on parenting stress: A randomised controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2016; 86 34–38. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kammerer M, Castro RTA, Glover V, Ramchandani P, Bennett P. A randomized controlled trial of internet based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus treatment as usual for pregnant women with high levels of depression at queen charlotte’s hospital. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2013; 16 S18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsh N, Webster J, Mihala G, Rickard CM. Devices and dressings to secure peripheral venous catheters: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017; 67 12–19. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngai FW, Wong PW, Chung KF, Leung KY. The effect of a telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy on quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung SS, Lee AM, Wong DF, Wong CM, Leung KY, Chiang VC, et al. A brief group intervention using a cognitive-behavioural approach to reduce postnatal depressive symptoms: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2016; 22 Suppl 2 S4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, Gallop R, Brown AP, Beck A. Staying well during pregnancy and the postpartum: A pilot randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016; 84(2): 134–145. 10.1037/ccp0000068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fathi-Ashtiani A, Ahmadi A, Ghobari-Bonab B, Azizi MP, Saheb-Alzamani SM. Randomized Trial of Psychological Interventions to Preventing Postpartum Depression among Iranian First-time Mothers. Int J Prev Med. 2015; 6 109 10.4103/2008-7802.169078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngai FW, Wong PW, Leung KY, Chau PH, Chung KF. The Effect of Telephone-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Postnatal Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2015; 84(5): 294–303. 10.1159/000430449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou Y, Hu P, Zhang Y, Lu Q, Wang D, Yin L, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy in combination with systemic family therapy improves mild to moderate postpartum depression. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2014; 36(1): 47–52. 10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Mahen HA, Woodford J, McGinley J, Warren FC, Richards DA, Lynch TR, et al. Internet-based behavioral activation—treatment for postnatal depression (Netmums): a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2013; 150(3): 814–822. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ammerman RT, Putnam FW, Altaye M, Teeters AR, Stevens J, Van Ginkel JB. Treatment of depressed mothers in home visiting: impact on psychological distress and social functioning. Child Abuse Negl. 2013; 37(8): 544–554. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milgrom J, Holt CJ, Gemmill AW, Ericksen J, Leigh B, Buist A, et al. Treating postnatal depressive symptoms in primary care: a randomised controlled trial of GP management, with and without adjunctive counselling. BMC Psychiatry. 2011; 11 95 10.1186/1471-244X-11-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrell CJ, Slade P, Warner R, Paley G, Dixon S, Walters SJ, et al. Clinical effectiveness of health visitor training in psychologically informed approaches for depression in postnatal women: pragmatic cluster randomised trial in primary care. Bmj. 2009; 338 a3045 10.1136/bmj.a3045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Austin MP, Frilingos M, Lumley J, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Roncolato W, Acland S, et al. Brief antenatal cognitive behaviour therapy group intervention for the prevention of postnatal depression and anxiety: a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2008; 105(1–3): 35–44. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milgrom J, Negri LM, Gemmill AW, McNeil M, Martin PR. A randomized controlled trial of psychological interventions for postnatal depression. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005; 44(Pt 4): 529–542. 10.1348/014466505X34200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Misri S, Reebye P, Corral M, Milis L. The use of paroxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy in postpartum depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004; 65(9): 1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooper PJ, Murray L, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression. I. Impact on maternal mood. Br J Psychiatry. 2003; 182 412–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Honey KL, Bennett P, Morgan M. A brief psycho-educational group intervention for postnatal depression. Br J Clin Psychol. 2002; 41(Pt 4): 405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chabrol H, Teissedre F, Saint-Jean M, Teisseyre N, Roge B, Mullet E. Prevention and treatment of post-partum depression: a controlled randomized study on women at risk. Psychol Med. 2002; 32(6): 1039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prendergast J, Austin MP. Early childhood nurse-delivered cognitive behavioural counselling for post-natal depression. Australasian Psychiatry. 2001; 9(3): 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scope A, Leaviss J, Kaltenthaler E, Parry G, Sutcliffe P, Bradburn M, et al. Is group cognitive behaviour therapy for postnatal depression evidence-based practice? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013; 13 321 10.1186/1471-244X-13-321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOC)

Raw data.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available in the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.