Abstract

Hamstring strain injuries are common among sports that involve sprinting, kicking, and high-speed skilled movements or extensive muscle lengthening-type maneuvers with hip flexion and knee extension. These injuries present the challenge of significant recovery time and a lengthy period of increased susceptibility for recurrent injury. Nearly one third of hamstring strains recur within the first year following return to sport with subsequent injuries often being more severe than the original. This high re-injury rate suggests that athletes may be returning to sport prematurely due to inadequate return to sport criteria. In this review article, we describe the epidemiology, risk factors, differential diagnosis, and prognosis of an acute hamstring strain. Based on the current available evidence, we then propose a clinical guide for the rehabilitation of acute hamstring strains and an algorithm to assist clinicians in the decision-making process when assessing readiness of an athlete to return to sport.

Keywords: Acute, Muscle, Performance, Physical therapy, Recurrence, Re-injury, Thigh

1. Introduction

There is a wide spectrum of hamstring-related injuries that can occur in the athlete. These include hamstring strains, complete and partial proximal hamstring tendon avulsions, ischial apophyseal avulsions, proximal hamstring tendinopathy, and referred posterior thigh pain.1, 2 Of these, hamstring strains are the most prevalent hamstring-related injury resulting in loss of time for athletes at all levels of competition.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Acute hamstring strains often result in significant recovery time and have a lengthy period of increased susceptibility for recurrent injury.4, 8 Approximately one-third of hamstring strains will recur, with the highest risk for injury recurrence being within the first 2 weeks of return to sport.2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 This high recurrence rate is suggestive of an inadequate rehabilitation program, a premature return to sport, or a combination of both. The consequences of recurrence are high as recurrent hamstring strains have been shown to result in significantly more time lost than first time hamstring strains.10 Therefore, the purpose of this review article was to provide a summary of the current evidence for clinicians to improve the quality of rehabilitation and decision-making for return to sport after a hamstring-related injury.

2. Epidemiology

There is an increased risk for acute hamstring strains in sports that involve sprinting, kicking, or high-speed skilled movements, such as football, soccer, rugby, and track,1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and in sports that involve extensive muscle lengthening-type maneuvers, such as dancing.1, 6, 8 Acute hamstring strains have been found to be more common in field sports (football, soccer, and field hockey) than in court sports (basketball, volleyball),7, 9 more common in competition than in practice,7, 13, 14 and more common in preseason than regular season and postseason.7 Most hamstring strains are from non-contact mechanisms7, 14 with the most common mechanisms being running and sprinting activities occurring during sport.7 Male athletes are 64% more likely to sustain an acute hamstring strain than female athletes.7, 9, 12, 15

A National Football League team published injury data, including data from preseason training camp from 1998 to 2007, and found that hamstring strains were the most common muscle strain and were the second most common injury, only surpassed by knee sprains.13 Hamstring strains were most common in running backs, defensive backs or safeties, and wide receivers.13 Injury data published from 51 professional soccer teams showed that hamstring strains were the most common injury, representing 12% of all injuries.14 Track and field injury data from the Penn Relays Carnival showed that hamstring strains were the most common injury, accounting for 24.1% of all injuries and greater than 75% of all lower extremity strain injuries.15

With running and sprinting being the most common activities of hamstring strain injury, identifying the alterations of gait mechanics that may be responsible has received attention. During the terminal swing phase of the running gait cycle, the hamstrings incur the greatest stretch and are active, eccentrically contracting to decelerate the lower limb in preparation for foot contact.6, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 It is important to note that hamstring length is not representative of muscle fiber strain. Fiorentino and colleagues19 showed that whole-fiber length change relative to the musculotendon unit length change remains relatively constant with increasing speed; however, peak local fiber strain relative to the strain of the musculotendon unit increases with speed, with the highest peak local fiber strain relative to the whole muscle fiber strain occurring at the fastest speed (100% maximum). Peak hamstring force and negative work also occur during this phase, most notably to the biceps femoris, and increase significantly with speed.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Chumanov and colleagues16 showed that peak hamstring force and negative work increased to the largest extent as sprinting speed was increased from submaximal to maximal sprinting speeds. The average peak net hamstring force and negative work increased from 36 N/kg and 1.4 J/kg at 80% speed to 52 N/kg and 2.6 J/kg at 100% speed, respectively. Furthermore, Silder and colleagues22 showed that as speed increased from 80% to 100%, biceps femoris activity during the terminal swing phase increased an average of 67%, while the semimembranosus and semitendinosus showed a 37% increase. The results of these studies offer insights and provide a possible explanation for the tendency of the biceps femoris to be more often injured than the semimembranosus and semitendinosus when running at high speed. In addition, these injuries typically occur along the intramuscular tendon and the adjacent muscle fibers.6, 23

In sports that involve extreme stretching movements, such as dancing, the semimembranosus is more commonly involved. Injury data published by Askling and colleagues24 on 15 professional dancers showed that all dancers were injured during slow hip flexion movements with knee extension, with the injury most commonly involving the semimembranosus (87%). More detailed anatomic and biomechanical studies are needed to further investigate the preference of injury to the semimembranosus vs. the semitendinosus and biceps femoris. These injuries typically occur more often at the proximal free tendon as opposed to the intramuscular tendon.2, 6, 24, 25

3. Risk factors

Acute hamstring strains often result in significant recovery time and have a lengthy period of increased susceptibility for recurrent injury.4, 8 Approximately one third of the hamstring injuries will recur with the highest risk for injury recurrence being within the first 2 weeks of return to sport.2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 This finding had led some to speculate that athletes may be returning to sport at a suboptimal level of performance due to ineffective rehabilitation or returning to sport prematurely due to inadequate return to sport criteria.2, 4, 6, 7, 11 Several other factors likely contribute to the high rate of recurrent injury, such as persistent weakness in the injured muscle, reduced extensibility of the musculotendinous unit due to residual scar tissue, and adaptive changes in the biomechanics and motor patterns of sporting movements following the original injury.5, 6

Previous research has identified multiple risk factors for hamstring injury. Non-modifiable risk factors include older age and prior history of hamstring strain.1, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 A prospective cohort study of male soccer players showed that 10.5% of players with a previous hamstring injury and 4.6% of players without a previous hamstring injury experienced a new hamstring injury during the season, indicating that athletes with a prior hamstring injury are at more than twice as high a risk of sustaining a new hamstring injury.28 Modifiable risk factors include hamstring weakness and fatigue,31, 32, 33, 34, 35 imbalances in hamstring eccentric and quadriceps concentric strength,34, 36, 37 decreased quadriceps flexibility,26 reduced hip flexor flexibility,26 and strength and coordination deficits of the pelvic and trunk musculature.4, 38, 39, 40 It is speculated that addressing each of these modifiable risk factors through rehabilitation programs could potentially decrease re-injury risk. Height, weight, and body mass index have been shown to have no influence on the incidence of hamstring strain injuries.29, 30, 41, 42

4. Differential diagnosis

Determining the exact source of injury is critical in determining the most appropriate treatment and expediting safe return to play. Considering the potential causes of posterior thigh pain, the differential diagnosis for acute hamstring strain injury includes hamstring tendon avulsions, ischial apophyseal avulsions, proximal hamstring tendinopathies, and referred posterior thigh pain.

Complete and partial avulsions of the proximal hamstring tendon are uncommon injuries, but can occur during sporting activities that generate forceful hip flexion moments while the knee is extending. Common sporting mechanisms include water skiing,43, 44, 45, 46 bull riding,44 tackling associated with rugby and football,47 and slips or falls associated with cross-country and downhill skiing.46 The athlete may report an audible pop and have significant pain with immediate loss of function. The athlete often presents with an inability or significant difficulty with performing a prone leg curl, an inability to fully extend and bear weight on the involved side, and significant gait abnormality.44, 45, 46, 47 Acutely, significant ecchymosis and a large hematoma are seen in the posterior thigh46, 47, 48 which will likely limit a clinician's ability to discern a palpable defect. In the subacute and chronic phases, once the hematoma has resolved, a palpable defect is often noted with active or resisted knee flexion, which produces a distal bulge in the retracted muscle.46, 47, 48 Another way to assess hamstring tendon integrity in the acute phase is to evaluate for the presence of a positive bowstring sign (absence of palpable tension in the distal hamstring tendons when the knee actively holds a flexed position due to lack of proximal hamstring tendon integrity).43 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most accurate imaging modality for the diagnosis of proximal hamstring avulsions.46, 47, 48, 49

Ischial apophyseal avulsions are more likely to occur in young athletes (13–16 years) when the apophysis has the least amount of bony bridging or fusion (open growth plate).49, 50 The mechanism of injury typically involves a forceful low-velocity overstretch, often with combined hip flexion and knee extension, which is common in dance and kicking.49, 50 The athlete may report an audible pop and have deep achy pain, especially when sitting.49 Clinical examination will likely reveal ischial tenderness, pain and weakness with strength testing of the hamstrings and gluteals, and pain with active and passive knee extension testing. Once pain has been controlled, length or flexibility testing of the hamstrings may actually reveal no deficit due to loss of the hamstring origin anchor point. If an ischial apophyseal avulsion is suspected, an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis can be utilized for definitive diagnosis.1, 49

Proximal hamstring tendinopathy, or high hamstring tendinopathy, is often insidious with a gradual onset of pain.51, 52 Pain in the proximal hamstring region is experienced during activity, when sitting on firm surfaces, or with prolonged sitting.51, 52, 53 Evidence suggests that it more commonly affects middle-aged athletes52 and endurance athletes (long distance runners, cross country skiers, and cyclists).51, 52, 53 Most athletes with proximal hamstring tendinopathy have tenderness to palpation on the ischial tuberosity, local discomfort with minimal to no weakness of the hamstrings and gluteals, and local discomfort with flexibility testing with minimal to no limitation of hamstring length.51, 52, 53 Specific clinical tests for high hamstring tendinopathy include the Puranen-Orava test, the bent-knee stretch test, and the modified bent-knee stretch test.54, 55

Causes of referred posterior thigh pain include piriformis syndrome, neural tension, lumbar disc herniation, or lumbar facet syndrome, which causes nerve root compression, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, and spondylogenic lesions.53, 56, 57 Athletes with referred posterior thigh pain will commonly have variable symptoms within the low back region, ranging from no back pain to significant back pain. Other symptoms include posterior thigh muscle cramping and tightness, numbness, tingling, and shooting pain.53, 56 Clinical examination will likely reveal reduced range of motion (ROM) or pain provocation with movement of the lumbar spine, tenderness or stiffness over the lumbar intervertebral or sacroiliac joints, a positive slump test, or a positive lumbar quadrant test.56 If clinical examination suggests a diagnosis of referred posterior thigh pain and advanced imaging for the hamstrings is negative, advance imaging for the spine may be warranted.

5. Prognosis

The severity of hamstring strains ranges on a continuum from very mild to very severe. When evaluating the prognosis for acute hamstring strains, important outcomes include potential time away from sport, return to pre-injury level of sport performance, and likelihood of re-injury. Attempts to determine the likelihood of these outcomes have centered on imaging of the injured muscle tendon unit, patient symptoms, specific clinical tests, and functional clinical tests.

Advanced musculoskeletal imaging, including MRI and ultrasound, are being implemented in an attempt to better identify and determine prognosis. These techniques provide a more objective measure and are frequently used to assess the severity and extent of injury with professional athletes. MRI studies of hamstring strains indicate that the length and cross-sectional area of the injury are directly proportional to the time for recovery from injury, with increased length and cross-sectional area resulting in greater time for recovery.11, 58, 59, 60 However, multiple MRI studies demonstrate that the severity of the initial injury is ineffective in predicting re-injury.61, 62 Thus, MRI of hamstring strains appears useful in estimating time for recovery from injury, but is limited in identifying individuals at risk for re-injury. Ultrasound as a prognostic indicator of time to recover from injury should be used with caution as a recent publication investigating soccer players with acute hamstring injuries showed no correlation between length of injury area, injury severity, and time to return to play.63

Various clinical criteria, when assessed within the first 5 days of initial injury, have been associated with a long recovery time (>40 days to return to sport), such as an initial visual analog scale pain score of greater than 6, pain during everyday activities for more than 3 days, popping sound during the injury, bruising, and greater than 15° difference in passive straightening of the injured limb compared to the uninjured limb.64 The time to walk test, which assesses an athlete's ability to walk without pain post-injury, has also been used to assess recovery time.65, 66 Australian Rules football players taking more than 1 day to walk pain-free following injury were 4 times more likely to take longer than 3 weeks to return to sport when compared with those walking pain-free within 1 day.65

The active ROM test assesses an athlete's ability to extend the knee while the hip is flexed at 90° in supine. Injury data published on 165 elite track and field athletes showed that athletes with a greater active knee extension ROM deficit required longer recovery.67, 68 When comparing active knee extension ROM deficit with full rehabilitation time, the average time to return to sport after initial injury was 6.9 days for <10° deficit, 11.7 days for 10°–19° deficit, 25.4 days for 20°–29° deficit, and 55.0 days for ≥30° deficit.67, 68 This test is traditionally used to assess hamstring flexibility. The formation of scar tissue does not occur until the proliferation stage of tissue healing69 and thus an acute active knee extension deficit is most likely related to pain and neurophysiological mechanisms occurring during the inflammatory stage of tissue healing.

The resisted ROM test can be used to assess an athlete's ability to resist knee extension at 90°, 45°, and 15° of knee flexion in prone.54, 70 Based on the length-tension curve and the internal torque-joint angle curve, it is expected that the hamstrings will demonstrate the greatest force at 90° due to the hamstrings being at optimum length and leverage.71 As the hamstrings are lengthened, such as when placed at 45° and 15° of knee flexion, the number of potential crossbridges decreases and the mechanical advantage decreases so that lesser amounts of active force are generated, even under conditions of full activation and effort.71, 72 Sole and colleagues72 showed that athletes with a recent hamstring injury demonstrate significantly decreased knee flexion torque in the lengthened range of contraction (approximately 5°–25° knee flexion). Athlete's demonstrating full isometric knee flexion force at 90°, with incremental reductions in isometric knee flexion force at 45° and 15°, have a better prognosis than athlete's demonstrating reduced isometric knee flexion force at 90° with further incremental reductions in isometric knee flexion force at 45° and 15°. The latter scenario indicates that the athlete has reduced force output even when the hamstrings are at optimum length and leverage.

The location of the point of maximum tenderness to palpation relative to the ischial tuberosity is associated with the recovery time. The more proximal the site of maximum pain, the longer the time needed to return to pre-injury level.23, 24, 73 In addition, the mechanism of injury and tissues injured have important prognostic value in estimating the duration of recovery needed to return to pre-injury level of performance.23, 24, 25, 73, 74 Injuries involving the intramuscular tendon and the adjacent muscle fibers (such as the biceps femoris during high-speed running23, 25) typically require a shorter recovery period than those involving the proximal free tendon (such as the semimembranosus during dance and kicking24, 25, 74). In 2007, Askling and colleagues23, 24 demonstrated that hamstring injuries occurring from sprinting-type activities resulted in an average of 16 weeks to return to pre-injury level in elite sprinters23 whereas hamstring injuries occurring from stretching-type activities resulted in an average of 50 weeks to return to pre-injury level in professional dancers.24 More recent data have demonstrated that return to sport may not be as lengthy as originally reported. In 2013, Askling and colleagues75 demonstrated that hamstring injuries occurring from sprinting-type activities resulted in an average of 23 days to return to sport whereas hamstring injuries occurring from stretching-type activities resulted in an average of 43 days to return to sport in elite football players.

Despite the differences in mechanism of injury, tissues involved, and recovery rates, current rehabilitation approaches do not differ greatly when treating high-speed running vs. overstretch injuries.2, 75, 76, 77 This topic is an area for future research and investigation as there seems to be room for developing rehabilitation exercises that are more specific with respect to injury type and location. Through examining the intensity and pattern of hamstring muscle activation in commonly used rehabilitation exercises, Mendiguchia and colleagues78 have shown that different rehabilitation exercises affect different patterns of muscle recruitment and that the degree of response differs between proximal and distal regions. Although these conclusions are based on unpublished data, they may suggest that the prescribed intervention will depend on the injured muscle and its specific anatomic location.

6. Current evidence of rehabilitation program interventions

The primary goal of the rehabilitation for hamstring strain injury is to allow the athlete to return to sport at a level of performance before the injury with minimal risk of recurrence of the injury. To do so, a rehabilitation program should address modifiable risk factors, such as hamstring weakness and fatigue;31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 79 imbalances in hamstring eccentric and quadriceps concentric strength;34, 36, 37 decreased quadriceps flexibility;26 reduced hip flexor flexibility;26 and strength and coordination deficits of the pelvic and trunk musculature.4, 38, 39, 40 Currently, there is no clear explanation or robust model that consistently demonstrates how all of these risk factors interact. Future research to look into the interrelationship between these different factors involved in hamstring strains would provide a better understanding of this multifactorial injury and may improve prevention and decrease risk for re-injury.

A rehabilitation program should address psychosocial factors, such as fear and apprehension. Insecurity when performing a ballistic hamstring flexibility test has been observed at the time of return to sport testing despite having passed common clinical strength and flexibility tests. Specifically, Askling and colleagues80 showed that there was a feeling of insecurity when performing this test with the injured leg in 95% of athletes.

Without adequate rehabilitation, athletes may experience persistent weakness in the injured muscle,3, 5, 22, 72, 81, 82, 83 reduced extensibility of the musculotendinous unit due to residual scar tissue,5, 59, 83, 84, 85 and adaptive changes in the biomechanics and motor patterns of sporting movements due to altered neuromuscular control.5, 16, 22, 72, 83, 86, 87

Sanfilippo and colleagues3 showed deficits in isokinetic knee flexion strength of the injured limb (9.6% deficit in peak torque and 6.4% deficit in work) at return to sport compared to the uninjured limb. Sole and colleagues72 showed deficits in eccentric flexor torque toward the hamstring lengthened range of the injured limb compared to the uninjured limb, especially in the fourth quartile (approximately 5° to 25° knee flexion). A recent study examining elite Australian footballers showed that previously injured athletes displayed smaller increases in eccentric hamstring strength compared with athletes who had no history of hamstring strain injuries.81 A shift in the isokinetic knee strength profile has been identified in previously injured limbs, indicating that athletes with a previous hamstring injury are at a greater than normal susceptibility for eccentric damage.88, 89 The mean optimum angle of peak torque for the previously injured hamstring muscles was at a significantly shorter muscle length (12.1° ± 2.7°, i.e., a more flexed knee) than for the hamstring muscles with no history of injury.88 A shorter than normal optimum length means that more of the muscle's working range is in the region of instability and damage on the length-tension curve, which could contribute to risk for re-injury.

Silder and colleagues85 showed that increased mechanical strains arise near the proximal biceps femoris musculotendinous junction during relatively low-load lengthening contractions, and that subjects with a prior hamstring injury presented with significantly greater muscle tissue strains when compared to those without a prior hamstring strain. Scar tissue has been observed as early as 6 weeks after an initial injury59 and found to persist on a long-term basis (at least 5–23 months post injury).84 Scar tissue is often observed along the musculotendinous junction adjacent to the site of prior injury, which may alter muscle contraction mechanics. In particular, the collagen fibers comprising remodeled tendon tend to be less well organized with different stiffness properties than normal tendon.84 Specifically, scar tissue may increase the overall mechanical stiffness of the tissue it replaces, which may require the muscle fibers to lengthen a greater amount to achieve the same overall musculotendon length relative to the pre-injury state.84 This suggests that residual scar tissue at the site of a prior musculotendon injury may adversely affect local tissue mechanics in a way that could contribute to risk for re-injury.

One of the most important components of rehabilitation is neuromuscular control. Sole and colleagues86 showed that there was an earlier onset of activation of the hamstring muscles during the transition from double- to single-leg stance in those with a previous hamstring injury compared to those without a previous hamstring injury. This suggests that there is an alteration in lower-limb proprioception and neuromuscular control following a hamstring injury. Neuromuscular control of the muscles affecting the length–tension relationship of the hamstrings based on their origin to the trunk and pelvis also needs to be addressed during rehabilitation. For example, Opar and colleagues15 found that the incidence of hamstring strains in track and field athletes were significantly greater in the 4 × 400 m relay when compared with the 4 × 100 m relay. This leads to speculation that there are important trunk and pelvic positional changes affecting the hamstrings that occur while sprinting on a curve vs. sprinting on a straightaway. The relationship between trunk and pelvic control to hamstring strain injury was confirmed by Chumanov and colleagues16, 87 who showed that the contralateral hip flexors (iliopsoas) have as large an influence on hamstring stretch as the hamstrings themselves. This influence occurs because the iliopsoas directly induces an increase in anterior pelvic tilt, which in turn necessitates greater hamstring stretch. Hip flexor muscle force induces hip flexion and a small amount of knee extension on the opposite limb, both of which act to increase hamstring stretch. Other proximal muscles affecting pelvis position, such as the abdominal obliques and erector spinae, also substantially influence hamstring stretch.16, 87 This influence demonstrates the importance of inter-segmental dynamics in which muscles can generate substantial accelerations about joints they do not span.

Determining the type of rehabilitation program that most effectively promotes muscle tissue and functional recovery is essential to minimize the risk of re-injury and to improve athlete performance. Both eccentric strength training10, 23, 24, 36, 90, 91, 92 and neuromuscular control exercises4, 38, 39, 40, 86 have been shown to reduce the likelihood of hamstring injury and are advocated by many as a part of the rehabilitation program following an acute hamstring strain. Askling and colleagues75, 76 demonstrated a significant reduction in time to return to sport when individuals with an acute hamstring injury were treated using a program aimed at loading the hamstrings during controlled lengthening (eccentric) exercises (L-protocol) compared to a program with less emphasis on eccentric exercises (C-protocol). In addition to a conventional hamstring rehabilitation program, each protocol consisted of 3 different exercises unique to each protocol, where Exercise 1 was aimed mainly at increasing flexibility, Exercise 2 was a combined exercise for strength and trunk and pelvis stabilization, and Exercise 3 was more of a specific strength training exercise. All exercises were performed in the sagittal plane. In elite football players,75 the L-protocol resulted in a mean of 28 days to return to sport and no re-injuries within 12 months whereas the C-protocol resulted in a mean of 51 days to return to sport and 1 re-injury within 12 months. In elite sprinters and jumpers,76 the L-protocol resulted in a mean of 49 days to return to sport and no re-injuries within 12 months whereas the C-protocol resulted in a mean of 86 days to return to sport and 2 re-injuries within 12 months. On this basis, a rehabilitation program consisting of mainly eccentric exercises is more effective than a rehabilitation program with less emphasis on eccentric exercises in promoting return to sport after acute hamstring injury. Proske and colleagues88 have shown that the performance of controlled eccentric exercises can facilitate a shift in peak force development to longer musculotendon lengths. Their initial data suggest that the incorporation of such exercises into rehabilitation may reduce hamstring re-injury rates as this shift in peak force development may help to restore optimal musculotendon length for tension production.

One common criticism of rehabilitation programs that only emphasize eccentric strength training is the lack of attention to musculature adjacent to the hamstrings. Neuromuscular control of the lumbopelvic region has been indicated as an important component for optimal function of the hamstrings during sporting activities16, 87 and should be an integral part to a comprehensive rehabilitation program. Sherry and Best4 demonstrated a significant reduction in injury recurrence when individuals with an acute hamstring injury were treated using a progressive agility and trunk stabilization (PATS) program compared to a progressive stretching and strengthening (STST) program. The PATS program consisted of primarily neuromuscular control exercises, beginning with early active mobilization in the frontal and transverse planes, and then progressing to movements in the sagittal plane. The average time required to return to sport for athletes in the PATS group was 22.2 days, while the average time for athletes in the STST group was 37.4 days. Compared to the STST group, there was a statistically significant reduction in injury recurrence in the PATS groups at 2 weeks (STST: 54.5% vs. PATS: 0%) and at 1 year (STST: 70% vs. PATS: 7.7%) after return to sport.

Silder and colleagues11 compared the PATS program to a progressive running and eccentric strengthening (PRES) program. No significant differences were found in time to return to sport when individuals with an acute hamstring injury were treated using a PATS program compared to a PRES program. The average time to return to sport for athletes in the PATS group was 25.2 days, while the average time for athletes in the PRES group was 28.8 days. Overall re-injury rates were low with 1 of 16 athletes in the PATS group and 3 of 13 athletes in the PRES group experiencing a re-injury within 12 months. Although both rehabilitation programs demonstrated excellent clinical results, no athlete showed complete resolution of injury as assessed on MRI following completion of rehabilitation despite meeting clinical clearance to return to sport (no pain, full ROM, and full strength). Therefore, regardless of the rehabilitation employed, clinical determinants of recovery as measured during the physical examination do not adequately represent complete muscle recovery and readiness for return to sport. This finding highlights the importance of a graduated return to the demands of full sporting activity and continued independent rehabilitation after return to sport to aid in minimizing re-injury risk.

Neural mobilization techniques have been recommended as part of the rehabilitation program if a positive active slump test is found during the examination.93 For those diagnosed with a hamstring strain with mild disruption of the muscle fibers, the inclusion of the slump stretch has been shown to reduce time away from sport.94 The use of neural mobilization techniques in the rehabilitation of more severe hamstring strains has not been investigated.

7. Proposed rehabilitation guideline

A guideline was proposed for the rehabilitation of hamstring strain injury (see Appendix in online version) based on current available evidence, including the integration of components of the PATS and the PRES rehabilitation programs.2, 4, 6, 11 This rehabilitation guideline is divided into 3 phases, with specific treatment goals and progression criteria for phase advancement and return to sport. The focus for Phase 1 is minimization of pain and edema, restoration of normal neuromuscular control at slower speeds, and prevention of excessive scar tissue formation while protecting the healing fibers from excessive lengthening. Phase 2 allows for increased intensity of exercise, neuromuscular training at faster speeds and larger amplitudes, and the initiation of eccentric resistance training. Phase 3 progresses to high-speed neuromuscular training and eccentric resistance training in a lengthened position in preparation for return to sport.

Symptom exacerbation due to exercise intensity and ROM is a potential complication of this rehabilitation guideline. All exercises should be progressed based on the athlete's tolerance and progression should be limited if the athlete reports pain, increased stiffness, or anxiety with movement. Clinical decision-making is crucial for safe progression of exercises without risking undue harm to the recovering athlete. It should be noted that this rehabilitation guideline (Appendix) is based primarily on the literature pertaining to hamstring strain injuries involving the intramuscular tendon and adjacent muscle fibers4, 11, 23, 25, 75, 76, 91 as there is a lack of published rehabilitation programs for those that involve the proximal free tendon. Modifications to the exercises, sports-specific movement, and progression criteria may need to be considered for injuries involving the proximal free tendons of the hamstring muscles.

8. Factors and criteria for return to sport

Currently, there is no consensus within the literature concerning return to sport decision-making given the lack of standardization and clear objective criteria. Often times, recommendations are vague, stating that athletes can be cleared to return to sport once full ROM, strength, and functional abilities (jumping, running, and cutting) can be performed without complaints of pain or stiffness.95 Askling and colleagues80 reported that the clinical examination of the injured leg should reveal no signs of remaining injury. These signs include no pain on palpation of the injured muscle, no difference in manual muscle testing between legs with no pain provocation, and <10% deficit with passive flexibility tests to that of the uninjured leg with no pain provocation. No pain on palpation of the injured muscle has been further validated as an important criteria for return to sport by De Vos and colleagues,61 who found that athletes with localized discomfort on hamstring palpation at time of return to sport were almost 4 times more likely to sustain a re-injury compared with athletes with absence of discomfort on palpation. A recent meta-analysis found that deficits in isometric strength and flexibility tend to resolve within 20–50 days following initial hamstring strain injury; however, deficits for dynamic measures of strength (concentric and eccentric strength, conventional and functional hamstring-to-quadricep strength ratios) were present at return to sport.82 This evidence suggests that it may be appropriate to monitor isometric strength and flexibility throughout rehabilitation, while dynamic measures of strength may hold more value at return to play.

Isokinetic strength testing should be performed under both concentric and eccentric conditions. Malliaropoulos and colleagues68 reported that isokinetic strength testing, measured at 60°/s and 180°/s, should result in a deficit of less than 5% compared with the injured side for clearance to return to sport. Multiple studies have also reported on the hamstring-to-quadricep strength ratio and have reported that less than a 5% bilateral deficit should exist in the ratio of eccentric hamstring strength (30°/s) to concentric quadriceps strength (240°/s).3, 96 In addition, the knee flexion angle at which peak concentric knee flexion torque occurs should be similar between limbs.88, 89 More specifically, the angle of peak torque should be within 5°2, 72, 89 and the time to peak torque should be within 10%2, 86 of the uninjured side. Delvaux and colleagues97 found that muscle strength performance was the second most common criteria (most common criteria was complete pain relief) for return to sport that is currently being used by sports medicine clinicians of professional soccer teams. The most common methods of strength assessment were manual muscle testing (80%) and isokinetic strength testing (75%) with 40% assessing eccentric quadricep strength, 60% assessing concentric quadricep strength, 75% assessing concentric hamstring strength, and 85% assessing eccentric hamstring strength. Although clinical research indicates comparison of a mixed ratio (eccentric hamstring strength to concentric quadriceps strength) to be the ideal method of assessment, only 30% of clinicians utilized this method. When assessing whether an athlete is ready to return to sport, 57% of clinicians reported tolerating ≤10% difference compared to the uninjured side whereas only 22% of clinicians reported tolerating ≤5% difference compared to the uninjured side. This signifies that there is a clear lack of consensus about the choice of assessment parameters and the specific values for whether or not to return an athlete to sport. An effort should be made to integrate clinical research results with those in actual sports medicine practice.

The active hamstring test, or H-test, is completed by performing a straight leg raise as fast as possible to the highest point without fear of injury. Askling and colleagues80 found a feeling of insecurity in 95% of the athletes when performing this test on the injured leg and that the mean angular hip flexion velocity was significantly lower in the injured leg compared to the uninjured leg. If insecurity is reported while performing this test, it is recommended that an additional 1–2 weeks of rehabilitation be allowed and the test repeated. This process then continues until no insecurity is reported.75, 76, 80 This test has been shown to be reliable and valid for detecting deficits in athletes with hamstring strains and provides useful additional information to the common clinical examination before returning an athlete to sport.80

An athlete's ability to return to sport may also be predicted by certain functional testing, such as the ability to perform a single leg hamstring bridge. Australian Rules football players demonstrating low hamstring strength, assessed via the single leg hamstring bridge test, were at increased risk for hamstring injury. A score of less than 20 repetitions is considered poor, 25 repetitions is considered average, and greater than 30 repetitions is considered good. The players who sustained a hamstring injury in this study were close to or below the poor level.32 Functional testing should also incorporate sport-related movements specific to the athlete with intensity and speed near maximum.2, 6, 97 All tasks should be completed without pain, limitation, or hesitation in order for the athlete to return to sport.

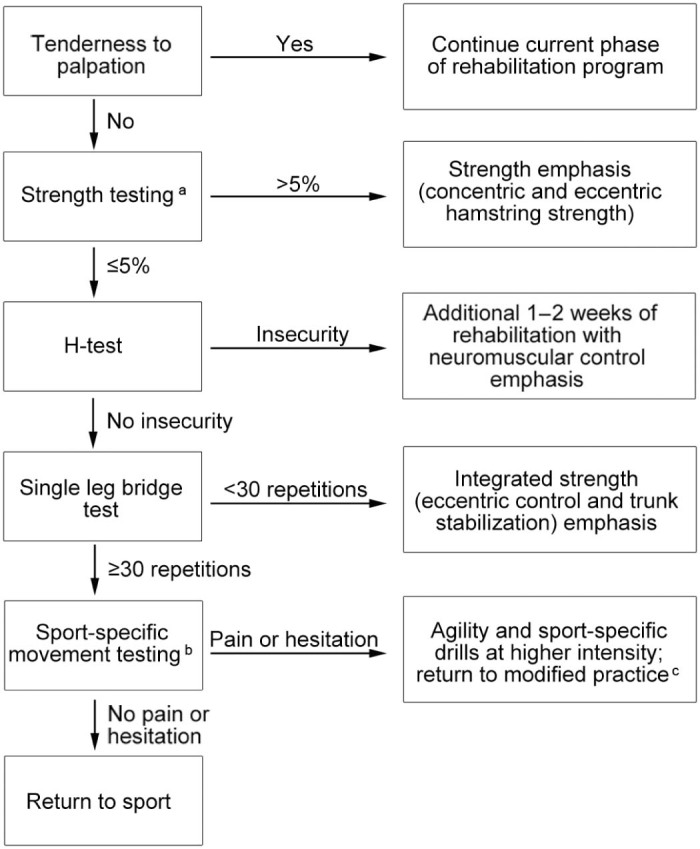

There is currently no strong evidence for MRI findings to serve as criteria for time to return to sport after an acute hamstring strain.61, 66, 98 Reurink and colleagues99 showed that fibrosis on MRI at return to sport after acute hamstring injury is not associated with re-injury risk. More specifically, 16 of 67 (24%) subjects without fibrosis on MRI and 10 of 41 (24%) subjects with fibrosis on MRI sustained a re-injury. These results emphasize that clinical and functional tests seem to be better associated with determining return to sport and risk of re-injury than findings on MRI. The authors of this review article have devised an algorithm to assist clinicians in the decision-making process when returning an athlete to sport (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for return to sport. aClinicians should utilize objective methods of strength assessment, including isokinetic strength testing (concentric hamstring strength, eccentric hamstring strength, eccentric hamstring strength to concentric quadriceps strength) or manual muscle testing with hand-held dynamometry or Kiio force sensors. bClinicians should incorporate movement specific to the athlete's sport, which may include accelerations, decelerations, rotations, sprinting, cutting, pivoting, jumping, and hopping. The movements should be performed with intensity and speed near maximum. cReturn to modified practice includes dynamic warm-up, sport-specific agility drills, and non-contact activities.

9. Summary

Hamstring strain injuries are one of the most common reasons for loss of playing time in athletes at all levels of competition. A comprehensive evaluation assists in coming to an accurate diagnosis and determining the type of rehabilitation program that most effectively promotes muscle tissue and functional recovery, which is essential to minimize the risk of re-injury and to optimize athlete performance. Without adequate rehabilitation, athletes may experience persistent weakness in the injured muscle and adaptive changes in the biomechanics and motor patterns of sporting movements. There is mounting evidence that rehabilitation strategies incorporating neuromuscular control; progressive agility and trunk stabilization; and eccentric strength training are more effective at promoting return to sport and minimize the risk of re-injury. Dynamic clinical and functional tests can be used to assess readiness for return to sport; however, an athlete should continue independent rehabilitation after return to sport to aid in minimizing re-injury risk.

Authors' contributions

LNE and MAS conceived of the article ideas and design; LNE drafted, revised, and edited the manuscript; MAS assisted in revising and editing the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of the presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2017.04.001

Appendix. Supplementary material

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Proposed guideline for the rehabilitation of acute hamstring strain injuries.

References

- 1.Sherry M. Examination and treatment of hamstring related injuries. Sports Health. 2012;4:107–114. doi: 10.1177/1941738111430197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherry M.A., Johnston T.S., Heiderscheit B.C. Rehabilitation of acute hamstring strain injuries. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34:263–284. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanfilippo J.L., Silder A., Sherry M.A., Tuite M.J., Heiderscheit B.C. Hamstring strength and morphology progression after return to sport from injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:448–454. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182776eff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherry M.A., Best T.M. A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:116–125. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.34.3.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orchard J., Best T.M. The management of muscle strain injuries: an early return versus the risk of recurrence. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12:3–5. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heiderscheit B.C., Sherry M.A., Silder A., Chumanov E.S., Thelen D.G. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40:67–81. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton S.L., Kerr Z.Y., Dompier T.P. Epidemiology of hamstring strains in 25 NCAA sports in the 2009–2010 to 2013–2014 academic years. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2671–2679. doi: 10.1177/0363546515599631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherry M.A., Best T.M., Silder A., Thelen D.G., Heiderscheit B.C. Hamstring strains: basic science and clinical research applications for preventing the recurrent injury. Strength Cond J. 2011;33:56–71. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross K.M., Gurka K.K., Conaway M., Ingersoll C.D. Hamstring strain incidence between genders and sports in NCAA athletics. Athl Ther Today. 2010;2:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks J.H., Fuller C.W., Kemp S.P., Reddin D.B. Incidence, risk, and prevention of hamstring muscle injuries in professional rugby union. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1297–1306. doi: 10.1177/0363546505286022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silder A., Sherry M.A., Sanfilippo J., Tuite M.J., Hetzel S.J., Heiderscheit B.C. Clinical and morphological changes following 2 rehabilitation programs for acute hamstring strain injuries: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:284–299. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cross K.M., Gurka K.K., Saliba S., Conaway M., Hertel J. Comparison of hamstring strain injury rates between male and female intercollegiate soccer athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:742–748. doi: 10.1177/0363546513475342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feeley B.T., Kennelly S., Barnes R.P., Muller M.S., Kelly B.T., Rodeo S.A. Epidemiology of national football league training camp injuries from 1998 to 2007. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1597–1603. doi: 10.1177/0363546508316021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekstrand J., Hägglund M., Waldén M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer) Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1226–1232. doi: 10.1177/0363546510395879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opar D.A., Drezner J., Shield A., Williams M., Webner D., Sennett B. Acute hamstring strain injury in track-and-field athletes: a 3-year observational study at the Penn Relay Carnival. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24 doi: 10.1111/sms.12159. e254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chumanov E.S., Heiderscheit B.C., Thelen D.G. The effect of speed and influence of individual muscles on hamstring mechanics during the swing phase of sprinting. J Biomech. 2007;40:3555–3562. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chumanov E.S., Heiderscheit B.C., Thelen D.G. Hamstring musculotendon dynamics during stance and swing phases of high-speed running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:525–532. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f23fe8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thelen D.G., Chumanov E.S., Best T.M., Swanson S.C., Heiderscheit B.C. Simulation of biceps femoris musculotendon mechanics during the swing phase of sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1931–1938. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000176674.42929.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiorentino N.M., Rehorn M.R., Chumanov E.S., Thelen D.G., Blemker S.S. Computational models predict larger muscle tissue strains at faster sprinting speeds. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:776–786. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schache A.G., Dorn T.W., Blanch P.D., Brown N.A., Pandy M.G. Mechanics of the human hamstring muscles during sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:647–658. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318236a3d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higashihara A., Ono T., Kubota J., Okuwaki T., Fukubayashi T. Functional differences in the activity of the hamstring muscles with increasing running speed. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:1085–1092. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.494308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silder A., Thelen D.G., Heiderscheit B.C. Effects of prior hamstring strain injury on strength, flexibility, and running mechanics. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2010;25:681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Askling C.M., Tengvar M., Saartok T., Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high-speed running: a longitudinal study including clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:197–206. doi: 10.1177/0363546506294679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Askling C.M., Tengvar M., Saartok T., Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during slow-speed stretching: clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and recovery characteristics. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1716–1724. doi: 10.1177/0363546507303563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Askling C., Saartok T., Thorstensson A. Type of acute hamstring strain affects flexibility, strength, and time to return to pre-injury level. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:40–44. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabbe B.J., Bennell K.L., Finch C.F., Wajswelner H., Orchard J.W. Predictors of hamstring injury at the elite level of Australian football. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verrall G.M., Slavotinek J.P., Barnes P.G., Fon G.T., Spriggins A.J. Clinical risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury: a prospective study with correlation of injury by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:435–440. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.6.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engebretsen A.H., Myklebust G., Holme I., Engebretsen L., Bahr R. Intrinsic risk factors for hamstring injuries among male soccer players: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1147–1153. doi: 10.1177/0363546509358381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foreman T.K., Addy T., Baker S., Burns J., Hill N., Madden T. Prospective studies into the causation of hamstring injuries in sport: a systematic review. Phys Ther Sport. 2006;7:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orchard J.W. Intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for muscle strains in Australian football. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:300–303. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290030801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worrell T.W. Factors associated with hamstring injuries: an approach to treatment and preventative measures. Sports Med. 1994;17:338–345. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199417050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freckleton G., Cook J., Pizzari T. The predictive validity of a single leg bridge test for hamstring injuries in Australian Rules football players. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agre J.C. Hamstring injuries. Proposed aetiological factors, prevention, and treatment. Sports Med. 1985;2:21–33. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198502010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Croisier J., Ganteaume S., Binet J., Genty M., Ferret J. Strength imbalances and prevention of hamstring injury in professional soccer players: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1469–1475. doi: 10.1177/0363546508316764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schache A.G., Crossley K.M., Macindoe I.G., Fahmer B.B., Pandy M.G. Can a clinical test of hamstring strength identify football players at risk of hamstring strain? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:38–41. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnason A., Andersen T.E., Holme I., Engebretsen L., Bahr R. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:40–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeung S.S., Suen A.M., Yeung E.W. A prospective cohort study of hamstring injuries in competitive sprinters: preseason muscle imbalance as a possible risk factor. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:589–594. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.056283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron M.L., Adams R.D., Maher C.G., Misson D. Effect of the HamSprint Drills training programme on lower limb neuromuscular control in Australian football players. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuszewski M., Gnat R., Saulicz E. Stability training of the lumbo-pelvo-hip complex influence stiffness of the hamstrings: a preliminary study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:260–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panayi S. The need for lumbar–pelvic assessment in the resolution of chronic hamstring strain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14:294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Visser H.M., Reijman M., Heijboer M.P., Bos P.K. Risk factors of recurrent hamstring injuries: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:124–130. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Beijsterveldt A.M., van de Port I.G., Vereijken A.J., Backx F.J. Risk factors for hamstring injuries in male soccer players: a systematic review of prospective studies. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23:253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birmingham P., Muller M., Wickiewicz T., Cavanaugh J., Rodeo S., Warren R. Functional outcome after repair of proximal hamstring avulsions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1819–1826. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakravarthy J., Ramisetty N., Pimpalnerkar A., Mohtadi N. Surgical repair of complete proximal hamstring tendon ruptures in water skiers and bull riders: a report of four cases and review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:569–572. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.015719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sallay P.I., Fiedman R.L., Coogan P.G., Garrett W.E. Hamstring muscle injuries among water skiers: functional outcome and prevention. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:130–136. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarimo J., Lempainen L., Mattila K., Orava S. Complete proximal hamstring avulsions: a series of 41 patients with operative treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1110–1115. doi: 10.1177/0363546508314427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konan S., Haddad F. Successful return to high level sports following early surgical repair of complete tears of the proximal hamstring tendons. Int Orthop. 2010;34:119–123. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0739-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wood D.G., Packham I., Trikha S.P., Linklater J. Avulsion of the proximal hamstring origin. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2365–2374. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gidwani S., Bircher M.D. Avulsion injuries of the hamstring origin: a series of 12 patients and management algorithm. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:394–399. doi: 10.1308/003588407X183427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wootton J.R., Cross M.J., Holt K.W. Avulsion of the ischial apophysis: the case for open reduction and internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:625–627. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B4.2380217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cacchio A., Rompe J.D., Furia J.P., Susi P., Santilli V., De Paulis F. Shockwave therapy for the treatment of chronic proximal hamstring tendinopathy in professional athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:146–153. doi: 10.1177/0363546510379324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lempainen L., Sarimo J., Mattila K., Vaittinen S., Orava S. Proximal hamstring tendinopathy: results of surgical management and histopathologic findings. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:727–734. doi: 10.1177/0363546508330129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fredericson M., Moore W., Guillet M., Beaulieu C. High hamstring tendinopathy in runners: meeting the challenges of diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation. Phys Sportsmed. 2005;33:32–52. doi: 10.3810/psm.2005.05.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reiman M.P., Loudon J.K., Goode A.P. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for assessment of hamstring injury: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:222–231. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cacchio A., Borra F., Severini G., Foglia A., Musarra F., Taddio N. Reliability and validity of three pain provocation tests used for the diagnosis of chronic proximal hamstring tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:883–887. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brunker P., Kahn K. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; Sydney, NSW: 2001. Clinical sports medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saikku K., Vasenius J., Saar P. Entrapment of the proximal sciatic nerve by the hamstring tendons. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76:321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen S.B., Towers J.D., Zoga A., Irrgang J.J., Makda J., Deluca P.F. Hamstring injuries in professional football players: magnetic resonance imaging correlation with return to play. Sports Health. 2011;3:423–430. doi: 10.1177/1941738111403107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Connell D.A., Schneider-Kolsky M.E., Hoving J.L., Malara F., Buchbinder R., Koulouris G. Longitudinal study comparing sonographic and MRI assessments of acute and healing hamstring injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:975–984. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.4.1830975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slavotinek J.P., Verrall G.M., Fon G.T. Hamstring injury in athletes: using MR imaging measurements to compare extent of muscle injury with amount of time lost from competition. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1621–1628. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Vos R.J., Reurink G., Goudswaard G.J., Moen M.H., Weir A., Tol J.L. Clinical findings just after return to play predict hamstring re-injury, but baseline MRI findings do not. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1377–1384. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koulouris G., Connell D.A., Brukner P., Schneider-Kolsky M. Magnetic resonance imaging parameters for assessing risk of recurrent hamstring injuries in elite athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1500–1506. doi: 10.1177/0363546507301258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petersen J., Thorborg K., Nielsen M.B., Skjødt T., Bolvig L., Bang N. The diagnostic and prognostic value of ultrasonography in soccer players with acute hamstring injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:399–404. doi: 10.1177/0363546513512779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guillodo Y., Here-Dorignac C., Thoribe B., Madouas G., Dauty M., Tassery F. Clinical predictors of time to return to competition following hamstring injuries. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4:386–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Warren P., Gabbe B.J., Schneider-Kolsky M., Bennell K.L. Clinical predictors of time to return to competition and of recurrence following hamstring strain in elite Australian footballers. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:415–419. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jacobsen P., Witvrouw E., Muxart P., Tol J.L., Whiteley R. A combination of initial and follow-up physiotherapist examination predicts physician-determined time to return to play after hamstring injury, with no added value of MRI. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:431–439. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malliaropoulos N., Papacostas E., Kiritsi O., Papalada A., Gougoulias N., Maffulli N. Posterior thigh muscle injuries in elite track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1813–1819. doi: 10.1177/0363546510366423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malliaropoulos N., Isinkaye T., Tsitas K., Maffulli N. Reinjury after acute posterior thigh muscle injuries in elite track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:304–310. doi: 10.1177/0363546510382857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jarvinen T.A., Jarvinen T.L., Kaariainen M., Kalimo H., Jarvinen M. Muscle injuries: biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:745–764. doi: 10.1177/0363546505274714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Starkey C., Ryan L. 2nd ed. F.A. Davis Company; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. Evaluation of orthopedic and athletic injuries. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Neumann D.A. 2nd ed. Mosby/Elsevier; St. Louis, MD: 2010. Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system: foundations for rehabilitation. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sole G., Milosavljevic S., Nicholson H.D., Sullivan S.J. Selective strength loss and decreased muscle activity in hamstring injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:354–363. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Askling C.M., Malliaropoulos N., Karlsson J. High-speed running type or stretching-type of hamstring injuries makes a difference to treatment and prognosis. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:86–87. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Askling C.M., Tengvar M., Saartok T., Thorstensson A. Proximal hamstring strains of stretching type in different sports: injury situations, clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics, and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1799–1804. doi: 10.1177/0363546508315892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Askling C.M., Tengvar M., Thorstensson A. Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite football: a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:953–959. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Askling C.M., Tengvar M., Tarassova O., Thorstensson A. Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite sprinters and jumpers: a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:532–539. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DeWitt J., Vidale T. Recurrent hamstring injury: consideration following operative and non-operative management. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9:798–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mendiguchia J., Alentorn-Geli E., Brughelli M. Hamstring strain injuries: are we heading in the right direction? Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:81–85. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.081695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fousekis K., Tsepis E., Poulmedis P., Athanasopoulos S., Vagenas G. Intrinsic risk factors of non-contact quadriceps and hamstring strains in soccer: a prospective study of 100 professional players. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:709–714. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Askling C.M., Nilsson J., Thorstensson A. A new hamstring test to complement the common clinical examination before return to sport after injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:1798–1803. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Opar D.A., Williams M.D., Timmins R.G., Hickey J., Duhig S.J., Shield A.J. The effect of previous hamstring strain injuries on the change in eccentric hamstring strength during preseason training in elite Australian footballers. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:377–384. doi: 10.1177/0363546514556638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maniar N., Shield A.J., Williams M.D., Timmins R.G., Opar D.A. Hamstring strength and flexibility after hamstring strain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:909–920. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fyfe J.J., Opar D.A., Williams M.D., Shield A.J. The role of neuromuscular inhibition in hamstring strain injury recurrence. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Silder A., Heiderscheit B.C., Thelen D.G., Enright T., Tuite M.J. MR observations of long-term musculotendon remodeling following a hamstring strain injury. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:1101–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0546-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Silder A., Reeder S.B., Thelen D.G. The influence of prior hamstring injury on lengthening muscle tissue mechanics. J Biomech. 2010;43:2254–2260. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sole G., Milosavljevic S., Nicholson H., Sullivan S.J. Altered muscle activation following hamstring injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:118–123. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thelen D.G., Chumanov E.S., Sherry M.A., Heiderscheit B.C. Neuromusculoskeletal models provide insights into the mechanisms and rehabilitation of hamstring strains. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2006;34:135–141. doi: 10.1249/00003677-200607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Proske U., Morgan D.L., Brockett C.L., Percival P. Identifying athletes at risk of hamstring strains and how to protect them. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31:546–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brockett C.L., Morgan D.L., Proske U. Predicting hamstring strain injury in elite athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:379–387. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000117165.75832.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schache A. Eccentric hamstring muscle training can prevent hamstring injuries in soccer players. J Physiother. 2012;58:58. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schmitt B., Tim T., McHugh M. Hamstring injury rehabilitation and prevention of reinjury using lengthened state eccentric training: a new concept. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7:333–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Askling C., Karlsson J., Thorstensson A. Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13:244–250. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Turl S.E., George K.P. Adverse neural tension: a factor in repetitive hamstring strain? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27:16–21. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.27.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kornberg C., Lew P. The effect of stretching neural structures on grade one hamstring injuries. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1989;10:481–487. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1989.10.12.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van der Horst N., van de Hoef S., Reurink G., Huisstede B., Backx F. Return to play after hamstring injuries: a qualitative systematic review of definitions and criteria. Sports Med. 2016;46:899–912. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0468-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Croisier J.L., Forthomme B., Namurois M.H., Vanderthommen M., Crielaard J.M. Hamstring muscle strain recurrence and strength performance disorders. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:199–203. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Delvaux F., Rochcongar P., Bruyere O., Bourlet G., Daniel C., Diverse P. Return-to-play criteria after hamstring injury: actual medicine practice in professional soccer teams. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13:721–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Reurink G., Brilman E.G., de Vos R.J., Maas M., Moen M.H., Weir A. Magnetic resonance imaging in acute hamstring injury: can we provide a return to play prognosis? Sports Med. 2015;45:133–146. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reurink G., Almusa E., Goudswaard G.J., Tol J.L., Hamilton B., Moen M.H. No association between fibrosis on magnetic resonance imaging at return to play and hamstring reinjury risk. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1228–1234. doi: 10.1177/0363546515572603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proposed guideline for the rehabilitation of acute hamstring strain injuries.