Abstract

Alterations in hemostasis are a characteristic feature of advanced liver disease. Patients with coagulopathy of advanced liver disease are prone to bleedings and also thromboembolic events. Under stable conditions, cirrhosis patients show alterations in both pro- and anticoagulatory pathways, frequently resulting in a rebalanced hemostasis. This review summarizes current recommendations of management during bleeding and prior to invasive procedures in patients with cirrhosis.

Keywords: Acute liver failure, Anticoagulation, Bleeding, Cirrhosis, Portal hypertension

Introduction

Alterations in hemostasis are a characteristic feature of advanced liver disease [1, 2, 3]. Traditionally, impaired protein synthesis (affecting pro- and anticoagulatory factors), endothelial dysfunction, reduced platelet count/function, and disturbances in fibrinolysis are considered crucial factors contributing to coagulopathy in advanced liver disease [1, 4, 5]. Additionally, portal hypertension is a major contributor to bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis [4]. However, patients with coagulopathy of advanced liver disease are not only prone to bleedings but also to thromboembolic events [2]. Factors associated with the pro- and anticoagulatory potential in patients with advanced liver disease are shown in table 1 [2, 4].

Table 1.

Pro- and anticoagulatory factors in patients with end-stage liver disease

| Increased bleeding risk | Increased risk for thrombosis/thromboembolism | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary hemostasis | platelet count ↓ functional defects nitric oxide ↑ prostacyclin ↑ |

vWF levels ↑ ADAMTS 13 ↓ |

| Secondary hemostasis | factor I, II, V, VII, IX, X levels ↓ |

antithrombin ↓ protein C and S ↓ factor VIII levels ↑ heparin cofactor 2 ↓ |

| Fibrinolysis | t-PA activity ↑ / PAI-1 ↓ factor XIII levels ↓ TAFI ↓ a2 antiplasmin ↓ |

plasminogen ↓ |

| Hemodynamic alterations | portal pressure ↑ | portal venous blood flow ↓ venous stasis due to immobilization |

vWF = von-Willebrand factor; ADAMTS 13 = a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13; t-PA = tissue plasminogen activator; PAI-1 = plasminogen activator inhibitor, TAFI = thrombinactivatable fibrinolysis inhibitor.

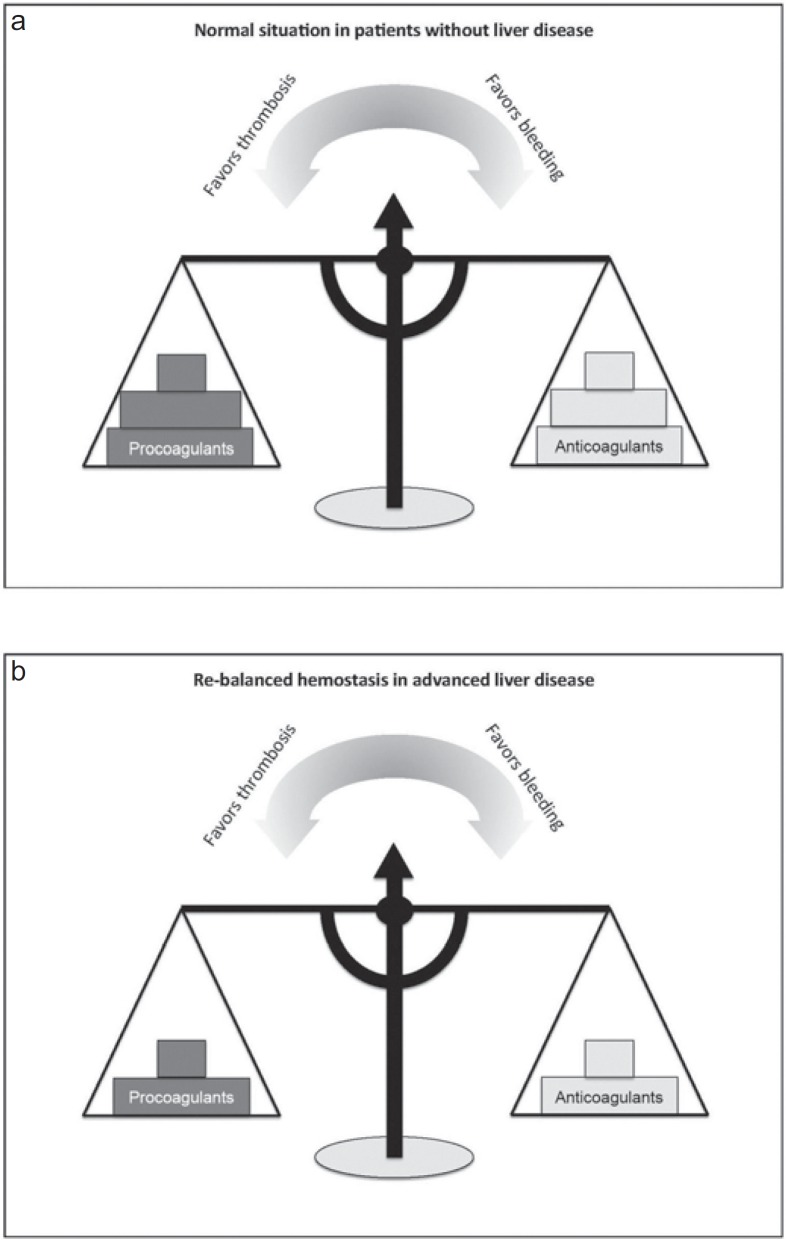

Thus, despite these abnormalities in hemostasis and global coagulation tests suggesting impaired coagulation, cirrhosis patients - at least under stable conditions - show alterations in both pro- and anticoagulatory pathways, frequently resulting in a rebalanced hemostasis (fig. 1) [2].

Fig. 1.

a, b Concept of (re-)balanced hemostasis in patients with and without liver disease.

Accordingly, global coagulation tests, such as international normalized ratio (INR), are insufficient to assess the coagulation system and bleeding risk in these patients [4, 6, 7].

Compared to patients without liver disease, however, this balance in hemostasis is relatively unstable. Especially bacterial infections and renal failure can lead to severe hemostatic alterations with consecutive bleeding diathesis in cirrhosis patients [1]. Therefore, risk for bleeding in cirrhosis seems to be particularly elevated in patients during decompensation, infections, or acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF).

Epidemiology and Clinical Impact of Bleedings in Cirrhosis in the Intensive Care Unit

Bleedings are still a frequent complication in cirrhosis patients and a common cause for intensive care unit (ICU) admission. According to the literature, the incidence of bleedings on ICU admission ranges between 15 and 61%. New onset of major bleeding in the ICU was found in 17–20% of cirrhosis patients [7, 8].

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is by far the most frequent site of major bleeding in cirrhosis and is usually related to esophageal and/or gastric varices.

Data on procedure-associated bleeding complications in cirrhosis patients are scarce. However, recently it has been shown that up to 5% of cirrhosis patients in the ICU develop major bleedings related to surgery/invasive procedures during the ICU stay [7].

Presence of bleeding is associated with high morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis, although its management has substantially improved since the introduction of gastric band ligation. The overall mortality of cirrhosis patients admitted to the ICU is still high and ranges between 32 and 66% in the recent literature [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of bleeding is usually based upon clinical signs (e.g. hematemesis, melena, obvious bleeding from puncture sites or surgical wounds) and laboratory (e.g. drop in hemoglobin, hematocrit, etc.), or may be diagnosed in the course of imaging procedures (e.g. sonography, computed tomography). If (upper) gastrointestinal bleeding is suspected, endoscopic evaluation is required.

Assessment of the Coagulation System in Cirrhosis

Conventional Laboratory Testing

Conventional coagulation testing - such as INR, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen levels, and platelet count - are of limited value in patients with liver cirrhosis [4, 15]. Yet, recent literature suggests that low fibrinogen levels, low platelet count, and increased aPTT are associated with major bleedings in cirrhosis patients in the ICU [7].

Viscoelastic Tests

Viscoelastic tests such as rotational thrombelastometry (ROTEM®) and thrombelastography (TEG®) are increasingly used to assess coagulation status in end-stage liver disease [16, 17]. Compared to a conventional coagulation parameter-guided transfusion regimen, a thrombelastography-guided strategy may reduce blood product use prior to invasive procedures in cirrhosis patients without increasing bleeding risk [18]. Moreover, use of a thombelastometry-guided transfusion strategy was associated with lesser use of red packed cells, plasma, and platelets, but higher transfusion rates of fibrinogen, thereby resulting in lower rates of acute renal failure, re-transplantation, and surgical revisions because of bleedings [19]. Yet, all of the mentioned studies have methodological limitations, as they were based on fixed transfusion thresholds derived from conventional coagulation testing, for which evidence is lacking. However, it has been recommended that viscoelastic testing should be considered, especially for periprocedural management [20].

Therapeutic Aspects and Recommendations for Cirrhosis Patients in the Intensive Care Unit

Most guidelines and consensus recommendations in this field are primarily dealing with the prevention and therapy of variceal bleeding only. Furthermore, data regarding management of hemostasis in cirrhosis patients, especially in the ICU, is limited. Thus, the following recommendations derived from different working groups are mostly eminence-based and primarily related to variceal bleeding.

Prophylactic Measures

1) Transfusion: In the absence of bleeding or planned invasive procedures, substitution/transfusion of blood or coagulation-products is not recommended [20, 21].

2) Pharmacologic therapy: Non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs) are a cornerstone of therapy in cirrhosis with significant portal hypertension [22, 23]. They have been shown to reduce portal hypertension and the risk for variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Yet, over the last years, doubts regarding the use of NSBBs in critically ill cirrhosis patients have been raised as a consequence of potential detrimental effects of NSBBs in cirrhosis patients with refractory ascites [24] or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) [25]]. Accordingly, it has been suggested that NSBBs may not be beneficial in cirrhosis patients who develop refractory ascites, hypotension, hepatorenal syndrome, SBP, sepsis, or severe alcoholic hepatitis [26]. While there is no data to support a general ban of beta-blockers in critically ill cirrhosis patients, discontinuation/temporary interruption/dose reduction of NSBBs has been suggested at the time of SBP, renal impairment, and hypotension [22, 23, 27].

3) Anticoagulation: Data regarding prophylactic anticoagulation in cirrhosis is scarce, and recommendations are partly inconsistent. Some authors advise against using (prophylactic) anticoagulation in cirrhosis [26]. Others suggest using anticoagulation only in patients with occlusive portal vein thrombosis [20]. Yet, at least in the absence of bleeding, there is no data to support withholding anticoagulation from patients with cirrhosis. In general, anticoagulation is safe and well tolerated in cirrhosis [28, 29]. Moreover, severity of disease, but not anticoagulation was associated with poor outcome in cirrhosis patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding [30]. In ICU patients with cirrhosis, there was no difference in the incidence of new-onset major bleedings between patients with and without anticoagulation [7]. Thus, the decision on whether or not to use anticoagulation in cirrhosis patients in the ICU remains an individual decision.

Periprocedural Management

Following recommendations should be considered prior to and during invasive procedures or surgery [20]:

- hemoglobin transfusion trigger of 7 g/dl;

- maintaining platelet count > 50 × 109/l;

- maintaining fibrinogen levels > 1.5 g/l;

- viscoelastic testing should be considered (but requires further evaluation);

- use of prothrombin complex before invasive procedures, preferably guided by viscoelastic testing.

Management during Bleedings

General Management

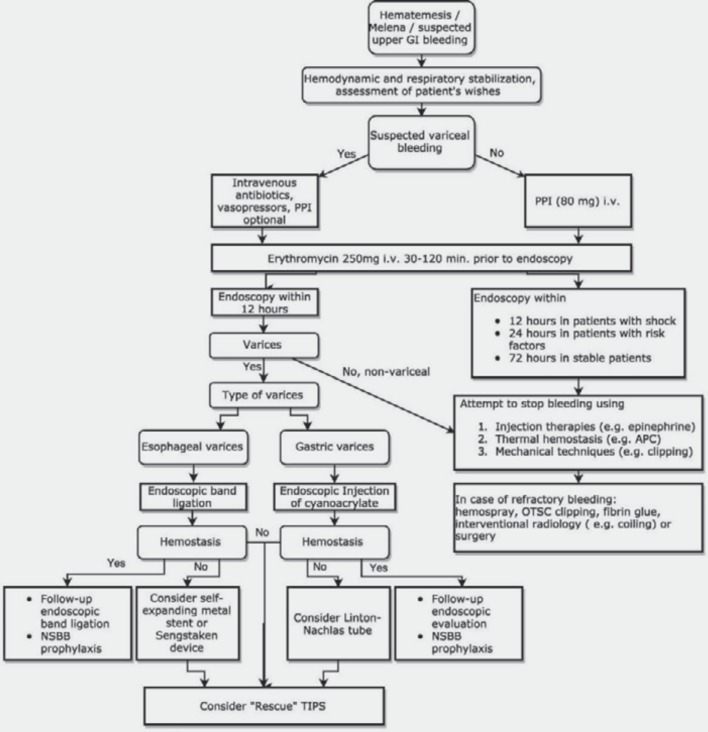

In accordance with recent guidelines, an algorithm for the general management of upper gastrointestinal bleedings in patients with liver cirrhosis is shown in fig. 2[31].

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for the management of upper gastrointestinal bleedings in patients with advanced liver disease. APC = Argon plasma coagulation; GI = gastrointestinal; NSBB = non-selective beta-blocker; OTSC = over-the-scope clip; PPI = proton pump inhibitor; TIPS = transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Moreover, in selected patients with refractory bleedings (e.g. complete portal vein thrombosis), surgical devascularization procedures (e.g. Hassab-Paquet or modified Sugiura procedure) may be life-saving [32, 33].

Blood and Hemostasis

In addition to the aforementioned procedures, monitoring of hemostasis and transfusion of blood and coagulation products remains a major aspect of therapy in cirrhosis patients with bleedings.

During upper gastrointestinal bleeding, a restrictive transfusion strategy (transfusion threshold of 7 g/dl) is associated with higher survival rates than a liberal transfusion strategy (transfusion threshold 9 g/dl) [34]. This applied also to patients with cirrhosis (especially Child-Pugh classes A & B). Furthermore, there was a trend for reduced incidence of variceal bleedings in patients treated with a restrictive transfusion regimen [34].

Data regarding potential benefits associated with the use of coagulation products during bleeding episodes in cirrhosis are scarce. However, although only limited evidence is available, the following aspects regarding management of hemostasis during active/persistent (gastrointestinal) bleeding in cirrhosis have recently been recommended for the management of critically ill patients with cirrhosis and also by the German Society of Gastroenterology (DGVS) [20, 31]:

- maintaining fibrinogen levels > 1.5 g/l [20] or at least > 1 g/l [31];

- maintaining prothrombin time > 50% [31];

- hemoglobin transfusion trigger of 7 g/dl [20], maintaining hemoglobin value between 7 and 9 g/dl [31];

- antifibrinolytic therapy (tranexamic acid or e-aminocaproic acid) use when hyperfibrinolysis is suspected or proven [20].

However, future studies are required to verify these recommendations and to assess the potential role of viscoelastic testing in cirrhosis patients with acute bleeding [20].

Conclusion

Bleedings remain a major concern in patients with liver cirrhosis in the ICU. Alterations of hemostasis in cirrhosis are complex, especially during decompensation and ACLF. The extent to which conventional laboratory tests reflect bleeding risk in these patients is unclear. Yet, thresholds for transfusions in response to conventional coagulation tests are part of most available guidelines. Future research efforts should focus on hemostasis in cirrhosis, especially during bleeding and critical illness, in order to improve management of coagulation and outcome in cirrhosis as well as to avoid unnecessary transfusions.

Disclosure Statement

Andreas Drolz and Arnulf Ferlitsch have nothing to disclose. Valentin Fuhrmann provides presentations for CSL Behring.

References

- 1.Caldwell SH, Hoffman M, Lisman T, et al. Coagulation disorders and hemostasis in liver disease: pathophysiology and critical assessment of current management. Hepatology. 2006;44:1039–1046. doi: 10.1002/hep.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lisman T, Caldwell SH, Burroughs AK, et al. Hemostasis and thrombosis in patients with liver disease: the ups and downs. J Hepatol. 2010;53:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaul V, Munoz S. Coagulopathy of liver disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2000;3:433–438. doi: 10.1007/s11938-000-0030-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valla D-C, Rautou P-E. The coagulation system in patients with end-stage liver disease. Liver Int. 2015;35((suppl 1)):139–144. doi: 10.1111/liv.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt BJ. Bleeding and coagulopathies in critical care. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:847–859. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsend JC, Heard R, Powers ER, Reuben A. Usefulness of international normalized ratio to predict bleeding complications in patients with end-stage liver disease who undergo cardiac catheterization. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1062–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drolz A, Horvatits T, Roedl K, et al. Coagulation parameters and major bleeding in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;64:556–568. doi: 10.1002/hep.28628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cholongitas E, Senzolo M, Patch D, et al. Risk factors, sequential organ failure assessment and model for end-stage liver disease scores for predicting short-term mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted to intensive care unit. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majumdar A, Bailey M, Kemp WM, Bellomo R, Roberts SK, Pilcher D. Declining mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis in Australia and New Zealand between 2000 and 2015. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1185–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levesque E, Saliba F, Ichaï P, Samuel D. Outcome of patients with cirrhosis requiring mechanical ventilation in ICU. J Hepatol. 2014;60:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olmez S, Gümürdülü Y, Tas A, Karakoc E, Kara B, Kidik A. Prognostic markers in cirrhotic patients requiring intensive care: a comparative prospective study. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu K-H, Jenq C-C, Tsai M-H, et al. Outcome scoring systems for short-term prognosis in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Shock. 2011;36:445–450. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31822fb7e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das V, Boelle P-Y, Galbois A, et al. Cirrhotic patients in the medical intensive care unit: early prognosis and long-term survival. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2108–2116. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3dea9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filloux B, Chagneau-Derrode C, Ragot S, et al. Short-term and long-term vital outcomes of cirrhotic patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1474–1480. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834059cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Violi F, Basili S, Raparelli V, Chowdary P, Gatt A, Burroughs AK. Patients with liver cirrhosis suffer from primary haemostatic defects? Fact or fiction? J Hepatol. 2011;55:1415–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saner FH, Kirchner C. Monitoring and treatment of coagulation disorders in end-stage liver disease. Visc Med. 2016;32:241–248. doi: 10.1159/000446304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S-C, Shieh J-F, Chang K-Y, et al. Thromboelastography-guided transfusion decreases intraoperative blood transfusion during orthotopic liver transplantation: randomized clinical trial. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2590–2593. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Pietri L, Bianchini M, Montalti R, et al. Thrombelastography-guided blood product use before invasive procedures in cirrhosis with severe coagulopathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2016;63:566–573. doi: 10.1002/hep.28148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leon-Justel A, Noval-Padillo JA, Alvarez-Rios AI, et al. Point-of-care haemostasis monitoring during liver transplantation reduces transfusion requirements and improves patient outcome. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;446:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadim MK, Durand F, Kellum JA, et al. Management of the critically ill patient with cirrhosis: a multidisciplinary perspective. J Hepatol. 2016;64:717–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson JC, Wendon JA, Kramer DJ, et al. Intensive care of the patient with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1864–1872. doi: 10.1002/hep.24622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Franchis R, Baveno VI Faculty Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310–335. doi: 10.1002/hep.28906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sersté T, Melot C, Francoz C, et al. Deleterious effects of beta-blockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology. 2010;52:1017–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.23775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, et al. Nonselective β blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1680–1681. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge PS, Runyon BA. Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:767–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1504367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, et al. U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut. 2015;64:1680–1704. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Menchise A, et al. Safety and efficacy of anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin for portal vein thrombosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:448–451. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b3ab44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delgado MG, Seijo S, Yepes I, et al. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulation on patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cerini F, Gonzalez JM, Torres F, et al. Impact of anticoagulation on upper-gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis. A retrospective multicenter study. Hepatology. 2015;62:575–583. doi: 10.1002/hep.27783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Götz M, Anders M, Biecker E, et al. S2k Guideline Gastrointestinal Bleeding - Guideline of the German Society of Gastroenterology DGVS (Article in German) Z Gastroenterol. 2017;55:883–936. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-116856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Král V, Klein J, Havlík R, Aujeský R, Utíkal P. Esophagogastric devascularization as the last option in the management of variceal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:244–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paquet KJ, Lazar A. The value collateralization and venous obstruction operations in acute bleeding esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis of the liver (Article in German) Chirurg. 1995;66:582–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]