Abstract

We aimed to test whether the calmodulin (CaM) inhibitors, calmidazolium (CZ) and N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulfonamide (W-7), can be used to assess lipid disorder by flow cytometry using Merocyanine 540 (M540). Boar spermatozoa were incubated in non-capacitating conditions for 10 min at room temperature with 1 μM CZ, 200 μM W-7, or 1 mM 8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP). Then, sperm were 1) directly evaluated, 2) centrifuged and washed prior to evaluation, or 3) diluted with PBS prior to evaluation. Direct evaluation showed an increase in high M540 fluorescence in spermatozoa treated with the inhibitors (4.7 ± 1.8 [control] vs. 70.4 ± 4.0 [CZ] and 71.4 ± 4.2 [W-7], mean % ± SD, P < 0.001); washing decreased the percentage of sperm showing high M540 fluorescence for W-7 (4.8 ± 2.2, mean % ± SD) but not for CZ (69.4 ± 3.9, mean % ± SD, P < 0.001), and dilution showed an increase in high M540 fluorescence for both CZ and W-7; 8-Br-cAMP did not induce a rise in sperm showing high M540 fluorescence. Therefore, special care must be taken when M540 is used in spermatozoa with CaM inhibitors.

Keywords: Boar spermatozoa, Calmodulin (CaM) inhibitors, Merocyanine 540 (M540)

Over the last few years, the use of flow cytometry in the field of spermatology has increased, and it is now commonly used to study various aspects of sperm functionality, including acrosome and membrane integrity, mitochondrial status, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and intracellular calcium levels, among others [1, 2]. Specifically, flow cytometry is used to assess the fertilizing ability or capacitation in spermatozoa [3, 4], as it is one of the most important fertilization-related events. Capacitation takes place in the female reproductive tract and is known to increase intracellular bicarbonate and calcium levels, which induces cholesterol efflux from the sperm plasmalemma and promotes phospholipid scrambling, thus enhancing its fluidity [5]. These early events trigger the activation of adenylyl cyclase, which stimulates cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production in turn inducing the activation of protein kinase A (PKA) and resulting in an increase in overall protein tyrosine phosphorylation (PY) [6, 7]. This complex process involves the activation of many intermediate proteins, among which, calmodulin (CaM) has been shown to play a central role due to its calcium-sensing function in ram [8], stallion [9, 10], boar [11], mouse [12], and human sperm [13]. In previous studies, capacitation was assessed by different assays, including the chlortetracycline (CTC) fluorescent assay, acrosome reaction (AR) induction by flow cytometry, and PY by western blotting or immunocytochemistry.

Another way to assess sperm capacitation is with Merocyanine 540 (M540), a lipophilic fluorescent dye. This probe gets incorporated into the phospholipids of the outer leaflet of the membrane [14, 15] and has been shown to be very sensitive for evaluating phospholipid packing of unilamellar and multilamellar lipid vesicles [16, 17]. In a previous study, Harrison et al. [18] described for the first time the use of M540 to assess membrane lipid disorder in spermatozoa. They associated enhanced M540 binding to the plasma membrane with increased lipid disorder, correlating this raise with the induction of capacitation. Since then, M540 has been used by many different laboratories around the world to study the capacitation status of spermatozoa from different species [19,20,21,22].

It should be mentioned that M540 does not only exhibit affinity for phospholipids but also binds to charged membranes [23]. As CaM inhibitors such as calmidazolium (CZ) and N-(6-Aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulfonamide (W-7) induce electrostatic changes in the cell membrane [24], it is reasonable to hypothesize that these inhibitors could alter the binding of M540 to the sperm membrane in the absence of phospholipid disorder. Thus, the objective of the present study was to explore whether the presence of these inhibitors under non-capacitating conditions affects the binding of M540 to boar sperm plasmalemma.

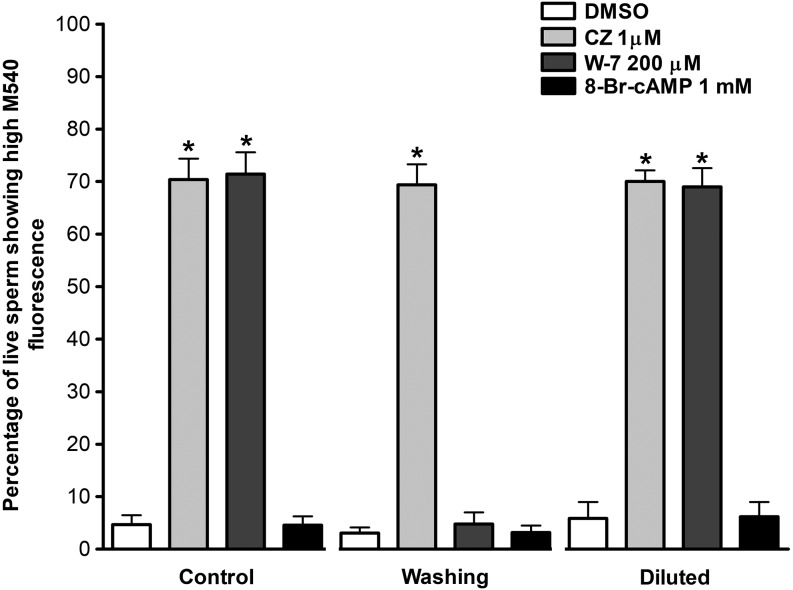

To determine the individual effects of CZ and W-7 on boar sperm membrane lipid disorder, spermatozoa were incubated in Tyrode’s basal medium (TBM) in the presence of CZ or W-7 for 10 min at room temperature. Various concentrations of these CaM inhibitors have been previously used in different species, ranging from 5 μM to 200 μM for CZ and 1 μM to 1 mM for W-7 [8, 10,11,12,13]. Specifically, in boar spermatozoa, W-7 has been used at 100 μM [11] and 200 μM [25], and CZ has been used at 4 μM [26]. When boar sperm were incubated in the presence of CaM inhibitors (1 μM CZ or 200 μM W-7), the percentage of viable spermatozoa presenting high M540 fluorescence increased significantly (4.7 ± 1.8 [control] vs. 70.4 ± 4.0 [CZ] and 71.4 ± 4.2 [W-7], mean % ± SD, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). The same effect was observed when spermatozoa were diluted in PBS before evaluation (5.9 ± 3.1 [control] vs. 70.0 ± 2.2 [CZ] and 69.0 ± 3.6 [W-7], mean % ± SD, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). However, when the inhibitors were removed from the medium by centrifugation and washing, the percentage of viable spermatozoa showing high M540 fluorescence was maintained for CZ-treated spermatozoa but not for W-7-treated spermatozoa (3.1 ± 1.0 [control] vs. 69.4 ± 3.9 [CZ] and 4.8 ± 2.2 [W-7], mean % ± SD, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). Interestingly, the addition of 1 mM 8-Br-cAMP did not change the percentage of viable spermatozoa showing high M540 fluorescence in any protocol used (Fig. 1; P ˃ 0.05). Additional concentrations of W-7 (100 μM) and CZ (2 and 5 μM) were also tested, and similar results were obtained (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effect of calmidazolium (CZ) and N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulfonamide (W-7) on high M540 fluorescence. Spermatozoa were incubated in the absence or presence of the inhibitors (1 μM CZ or 200 μM W-7) or with 1 mM 8-Br-cAMP in TBM for 10 min at room temperature and analyzed by flow cytometry directly (Control), after washing to remove the inhibitors (Washing), or after dilution in PBS (Diluted). Results are expressed as the percentage of viable spermatozoa (Yopro-1 negative) showing high M540 fluorescence (mean ± SD), n = 7; * P < 0.001.

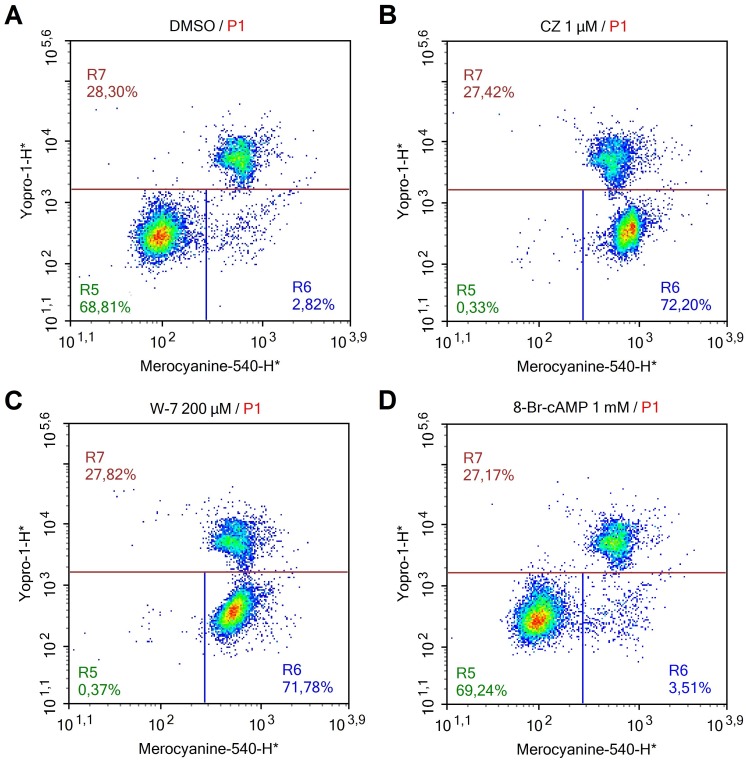

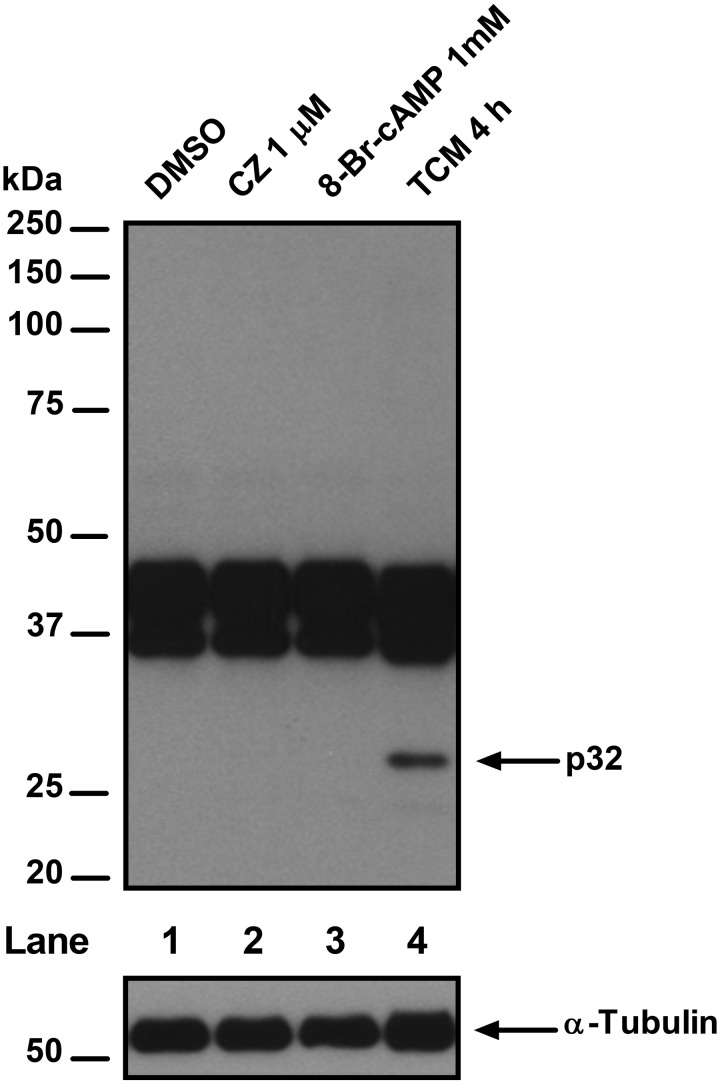

These results indicate that, under our assay conditions (10 min at room temperature in TBM), the presence of W-7 or CZ in the medium per se increases the percentage of live spermatozoa showing high M540 fluorescence (Figs. 1 and 2). However, this increase was not related to the increase in membrane lipid disorder that is associated with sperm capacitation, as the addition of the cAMP analogue 8-Br-cAMP did not induce a further increase in high M540 fluorescence (Figs. 1 and 2) as expected when capacitation is properly induced [28]. This assumption is made based on our western blotting results (Fig. 3) in which the tyrosine phosphorylation levels of the p32 protein [27], a well-recognized marker of capacitation in boar spermatozoa, did not increase in the presence of CZ (an inhibitor that increased the percentage of spermatozoa showing high M540 fluorescence in the three protocols used). Thus, another membrane change is likely the cause of the raise in high M540 fluorescence observed in boar spermatozoa. It has been shown that CZ and W-7 are amphipathic weak bases that bind to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, reducing its net negative charge [24]. This decrease in the overall negative charge of the membrane induced by the inhibitors could be responsible for the increased binding of M540 to boar sperm membrane, as it has been reported that negative charges on the plasmalemma strongly decrease the presence of M540 monomers in a lipid bilayer [23]. The differences observed between CZ and W-7 on the spermatozoa showing high M540 fluorescence after removal of the inhibitors by centrifugation (Fig. 1) could be explained by the affinity of the inhibitors for the plasma membrane; the affinity of CZ is > 100-fold stronger than that of W-7 [24], thus the effect of CZ on the plasma membrane is unaffected disregarding the protocol used. Furthermore, W-7 is a reversible CaM inhibitor, as stated by the manufacturer, which explains the lack of an effect on high M540 fluorescence after removal by centrifugation and washing. Thus, 200 μM W-7 could be used to study the lipid organization of boar sperm plasma membrane using M540 by flow cytometry if this inhibitor is removed from the medium prior to flow cytometric evaluation, unlike 1 μM CZ, which causes an increase in high M540 fluorescence that is not likely associated with capacitation. In addition, the use of these inhibitors (CZ and W-7), at least at the concentrations tested in the present report, is incompatible with an accurate evaluation of the organization status of the lipids in the sperm membrane in boar using M540 when the samples are diluted prior to flow cytometry analysis.

Fig. 2.

Representative dot plots for the different spermatozoa treatments using the dilution protocol (A: control; B: 1 μM CZ; C: 200 μM W-7; and D: 1 mM 8-Br-cAMP). R5: live spermatozoa (YoPro-1 negative) showing low M540 fluorescence; R6: live spermatozoa (YoPro-1 negative) showing high M540 fluorescence; R7: dead spermatozoa (YoPro-1 positive).

Fig. 3.

Effect of calmidazolium (CZ) on tyrosine phosphorylation of boar sperm proteins. Spermatozoa were incubated in the absence or presence of 1 μM CZ or 1 mM 8-Br-cAMP in TBM for 10 min at room temperature or 4 h in TCM at 38.5ºC (to induce sperm capacitation). After incubation, spermatozoa were centrifuged, lysed, and the sperm proteins were analyzed by western blotting. The immunoblot shown (upper panel) is a representative of five replicates (n = 5); the p32 protein (arrow) is phosphorylated after incubation in TCM (positive control). As a loading control, an antibody against α-tubulin was included (lower panel).

Our results should be carefully considered when these CaM inhibitors or other types of inhibitors that could potentially alter the sperm membrane charge are used to evaluate sperm membrane lipid disorder using M540.

Methods

Medium

Tyrode’s basal medium (TBM; 96 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.3 mM NaH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 21.6 mM sodium lactate, 20 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EGTA) was used as the non-capacitating medium. A variant of TBM was made omitting EGTA and adding 1 mM CaCl2, 15 mM NaHCO3 and 3 mg/ml BSA; this medium is referred to as Tyrode’s complete medium (TCM). All media were prepared on the day of use and adjusted to pH 7.45. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise stated.

Semen collection and processing

Ejaculates were purchased from a commercial boar station (Tecnogenext, S.L., Mérida, Spain). Duroc boars were maintained according to institutional and European regulations. To avoid individual variability between boars in each experiment, semen from three different males was pooled, centrifuged at 2100 × g for 2 min at room temperature (RT; 22–25˚C), washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and diluted in TBM or TCM to a final concentration of 30–50 × 106/ml. After sperm dilution, 0.25-ml aliquots of the sample were placed in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes in the presence of 1 μM CZ (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), 200 μM W-7, or 1 mM 8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP), a cAMP analogue that was used as positive control to increase sperm membrane lipid disorder [28]. Spermatozoa were incubated in TCM for 4 hours at 38.5°C in air to induce capacitation; this protocol was chosen based on previous studies showing tyrosine phosphorylation of the p32 protein by western blotting and chlortetracycline staining compatible with capacitation in boar sperm [27]. Control samples were incubated with 0.2% DMSO, the concentration in which the inhibitors were dissolved. Sperm samples incubated in TBM were processed after 10 min at room temperature and handled as follows: 1) directly evaluated by flow cytometry; 2) centrifuged and washed with PBS to remove the inhibitors before flow cytometry analysis, or c) diluted (100 μl of semen in 400 μl of PBS) before flow cytometry, a common protocol used in many laboratories.

Flow cytometry

Samples were analyzed using an ACEA NovoCyteTM flow cytometer (ACEA Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) equipped with a blue/red laser (488/640 nm). Flow cytometer performance was ensured by using fluorescent validation particles (NovoCyteTM Quality Control [QC] Particles; ACEA Biosciences) to check the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and the coefficient of variance (CV) of FSC, FITC (BL-1 channel), and PE (BL-2 channel). Flow cytometry experiments and data analysis were performed using ACEA Novo ExpressTM software (ACEA Biosciences). Forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) were used to gate the sperm population and exclude debris. Spermatozoa were analyzed at a rate of 400–800 cells/sec, and data were collected for 10,000 cells in each treatment.

Evaluation of plasma membrane lipid organization by flow cytometry

Sperm plasma membrane lipid organization and viability were simultaneously assessed by staining with M540 and YoPro-1 (Molecular Probes, Leiden, the Netherlands), respectively, using a 488-nm laser. Samples were incubated with YoPro-1 (75 nM) and M540 (6 µM) at 38.5°C for 15 min. M540 exhibits high affinity for membranes with increased lipid disorder, showing high fluorescence that is detected with a 572 ± 28 nm band pass filter. Sperm viability was evaluated with YoPro-1, a non-permeable viability stain that penetrates spermatozoa with damaged membranes, showing green fluorescence that is detected with a 530 ± 30 nm band-pass filter. Results are expressed as the percentage of viable cells (YoPro-1 negative) with high M540 fluorescence.

Western blotting

After incubation, spermatozoa were processed as described previously by González-Fernández et al. [10]. Briefly, spermatozoa were lysed, and their protein content was determined with the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Then, protein samples (15 μg) were loaded and electrophoresed in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). To detect tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins, the membrane was incubated with an anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (clone 4G10) from Millipore (diluted 1:5000, v/v, in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 solution [TBS-T] containing 3% BSA) overnight at 4°C. As a loading control, α-tubulin levels were detected using an anti α-tubulin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; diluted 1:500, v/v, in TBS-T with 3% BSA) overnight at 4°C. After incubation with the primary antibodies, the membranes were incubated for 45 min at room temperature with a secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; diluted 1:5000, v/v, in TBS-T containing 3% BSA).

Statistical analysis

A Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on ranks followed by the Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used to compare different treatments. Values are expressed as the mean percentage ± standard deviation (SD). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SigmaPlot software (ver. 12.0) for Windows (Systat Software, Chicago, IL, USA).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) of the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (AGL2015-73249-JIN and AGL2017-84681-R) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) and Junta de Extremadura-FEDER (GR15118 and IB16159). V Calle-Guisado was supported by a pre-doctoral grant (FPU-014/03449) from the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport.

References

- 1.Petrunkina AM, Harrison RA. Cytometric solutions in veterinary andrology: Developments, advantages, and limitations. Cytometry A 2011; 79: 338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutovsky P. New Approaches to Boar Semen Evaluation, Processing and Improvement. Reprod Domest Anim 2015; 50(Suppl 2): 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang MC. Fertilizing capacity of spermatozoa deposited into the fallopian tubes. Nature 1951; 168: 697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin CR. Observations on the penetration of the sperm in the mammalian egg. Aust J Sci Res, B 1951; 4: 581–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin SK, Yang WX. Factors and pathways involved in capacitation: how are they regulated? Oncotarget 2017; 8: 3600–3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visconti PE, Bailey JL, Moore GD, Pan D, Olds-Clarke P, Kopf GS. Capacitation of mouse spermatozoa. I. Correlation between the capacitation state and protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Development 1995; 121: 1129–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visconti PE, Moore GD, Bailey JL, Leclerc P, Connors SA, Pan D, Olds-Clarke P, Kopf GS. Capacitation of mouse spermatozoa. II. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation and capacitation are regulated by a cAMP-dependent pathway. Development 1995; 121: 1139–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colás C, Grasa P, Casao A, Gallego M, Abecia JA, Forcada F, Cebrián-Pérez JA, Muiño-Blanco T. Changes in calmodulin immunocytochemical localization associated with capacitation and acrosomal exocytosis of ram spermatozoa. Theriogenology 2009; 71: 789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.González-Fernández L, Macías-García B, Velez IC, Varner DD, Hinrichs K. Calcium-calmodulin and pH regulate protein tyrosine phosphorylation in stallion sperm. Reproduction 2012; 144: 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Fernández L, Macías-García B, Loux SC, Varner DD, Hinrichs K. Focal adhesion kinases and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases regulate protein tyrosine phosphorylation in stallion sperm. Biol Reprod 2013; 88: 138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Wang L, Li Y, Zhao N, Zhen L, Fu J, Yang Q. Calcium regulates motility and protein phosphorylation by changing cAMP and ATP concentrations in boar sperm in vitro. Anim Reprod Sci 2016; 172: 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarrete FA, García-Vázquez FA, Alvau A, Escoffier J, Krapf D, Sánchez-Cárdenas C, Salicioni AM, Darszon A, Visconti PE. Biphasic role of calcium in mouse sperm capacitation signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol 2015; 230: 1758–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad K, Bracho GE, Wolf DP, Tash JS. Regulation of human sperm motility and hyperactivation components by calcium, calmodulin, and protein phosphatases. Arch Androl 1995; 35: 187–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lelkes PI, Miller IR. Perturbations of membrane structure by optical probes: I. Location and structural sensitivity of merocyanine 540 bound to phospholipid membranes. J Membr Biol 1980; 52: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langner M, Hui SW. Merocyanine interaction with phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1993; 1149: 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson P, Mattocks K, Schlegel RA. Merocyanine 540, a fluorescent probe sensitive to lipid packing. Biochim Biophys Acta 1983; 732: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu H, Hui SW. Merocyanine 540 as a probe to monitor the molecular packing of phosphatidylcholine: a monolayer epifluorescence microscopy and spectroscopy study. Biochim Biophys Acta 1992; 1107: 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison RA, Ashworth PJ, Miller NG. Bicarbonate/CO2, an effector of capacitation, induces a rapid and reversible change in the lipid architecture of boar sperm plasma membranes. Mol Reprod Dev 1996; 45: 378–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinart E, Yeste M, Puigmulé M, Barrera X, Bonet S. Acrosin activity is a suitable indicator of boar semen preservation at 17°C when increasing environmental temperature and radiation. Theriogenology 2013; 80: 234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calle-Guisado V, Bragado MJ, García-Marín LJ, González-Fernández L. HSP90 maintains boar spermatozoa motility and mitochondrial membrane potential during heat stress. Anim Reprod Sci 2017; 187: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leahy T, Rickard JP, Aitken RJ, de Graaf SP. Penicillamine prevents ram sperm agglutination in media that support capacitation. Reproduction 2016; 151: 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rathi R, Colenbrander B, Bevers MM, Gadella BM. Evaluation of in vitro capacitation of stallion spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 2001; 65: 462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mateasik A, Sikurová L, Chorvát D., Jr Interaction of merocyanine 540 with charged membranes. Bioelectrochemistry 2002; 55: 173–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sengupta P, Ruano MJ, Tebar F, Golebiewska U, Zaitseva I, Enrich C, McLaughlin S, Villalobo A. Membrane-permeable calmodulin inhibitors (e.g. W-7/W-13) bind to membranes, changing the electrostatic surface potential: dual effect of W-13 on epidermal growth factor receptor activation. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 8474–8486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harayama H, Noda T, Ishikawa S, Shidara O. Relationship between cyclic AMP-dependent protein tyrosine phosphorylation and extracellular calcium during hyperactivation of boar spermatozoa. Mol Reprod Dev 2012; 79: 727–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson RN, Ashraf M, Russell LD. Effect of calmodulin antagonists on CA2+ uptake by boar spermatozoa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1983; 114: 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bravo MM, Aparicio IM, Garcia-Herreros M, Gil MC, Peña FJ, Garcia-Marin LJ. Changes in tyrosine phosphorylation associated with true capacitation and capacitation-like state in boar spermatozoa. Mol Reprod Dev 2005; 71: 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadella BM, Harrison RA. The capacitating agent bicarbonate induces protein kinase A-dependent changes in phospholipid transbilayer behavior in the sperm plasma membrane. Development 2000; 127: 2407–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]