Abstract

Silymarin (SM), a standardized extract derived from Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn, is primarily composed of flavonolignans, with silibinin (SB) as its major active constituent. The present study aimed to evaluate the antigenotoxic activities of SM and SB using the alkaline comet assay in whole blood cells and to assess their effects on the expression of genes associated with carcinogenesis and chemopreventive processes. Different concentrations of SM or SB (1.0, 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 mg/ml) were used in combination with the DNA damage-inducing agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS, 800 μM) to evaluate their genoprotective potential. To investigate the role of SM and SB in modulating gene expression, we performed quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of five genes that are known to be involved in DNA damage, carcinogenesis, and/or chemopreventive mechanisms. Treatment with SM or SB was found to significantly reduce the genotoxicity of MMS, upregulate the expression of PTEN and BCL2, and downregulate the expression of BAX and ABL1. We observed no significant changes in ETV6 expression levels following treatment with SM or SB. In conclusion, both SM and SB exerted antigenotoxic activities and modulated the expression of genes related to cell protection against DNA damage.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, 70% to 95% of the world's population rely on traditional medicine for primary health care, and most health practices involve the use of plant extracts or their active components [1]. Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn, popularly known as milk thistle, is one of the most widely used herbs worldwide. S. marianum has been well-known since ancient times and has been mostly used in traditional European and Asian medicine for treatment of liver disorders [2].

The medicinal properties of S. marianum are attributed to its ability to accumulate bioactive flavonolignan complexes, which are referred to as silymarin (SM). S. marianum contains approximately 70% to 80% flavonolignans (silymarin complex), small amounts of flavonoids, 20% to 30% fatty acids, and other polyphenolic compounds. The flavonolignan mixture present in S. marianum mainly consists of silibin (SB), also known as silibinin, the major bioactive component of the extract. Milk thistle extract is currently marketed worldwide as silymarin and silibinin under various trade names, such as Siliphos, Silipide, and Legalon [3].

The effects of SM and SB have been investigated in mice, rats, rabbits, and dogs and results demonstrated that their acute, subacute, and chronic toxicities are very low. SM and SB are primarily used for the treatment of various liver disorders that are characterized by degenerative necrosis and functional impairment, such as chronic inflammatory diseases, cirrhosis, and toxic liver damage [4]. In addition, SM and SB are well documented to exhibit various biological and pharmacological activities, including antioxidant [5], antidiabetic [6], anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects [7].

The pharmacological activities and toxicological safety of SM and SB have been extensively studied both in vitro and in vivo. However, little is known about their protective effects on the genetic material. Numerous phytochemicals have been reported to interfere with specific stages of carcinogenesis, and multiple mechanisms have been shown to account for the anticarcinogenic properties of dietary constituents [8].

Analysis of genes related to DNA damage, carcinogenesis, and/or chemoprevention can help elucidate the mechanisms by which dietary supplements can exert protective effects on DNA [9–13]. Thus, given the limited knowledge of the chemopreventive effects of SM and SB, analysis of the expression patterns of the tumor suppressors genes ETV6 and PTEN, the cell death regulators BCL2 and BAX (pro/antiapoptotic processes), and the protooncogene ABL1 can reveal the molecular basis underlying the effects of SM and SB.

Considering the biological activities presented by SM and SB, as well as their widespread use as herbal medicines, the present study aimed to evaluate the antigenotoxic activities of SM and SB using the comet assay and to evaluate the expression patterns of genes that are known to be associated with carcinogenesis and chemopreventive processes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Silymarin (SM, S0292), silibinin (SB, S0417), RPMI 1640 medium, methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), ethidium bromide, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), NaCl, and Triton X-100 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Low melting point agarose and normal melting point agarose were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Na2EDTA, Tris base, and Tris-HCl were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA).

2.2. Cell Treatment

Peripheral blood was obtained through venous puncture from three young and healthy volunteers who had no history of smoking or drinking. Our work was approved by the Human and Animal Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Goiás (CEPMHA/HC/UFG n. 016/2011). Whole blood was treated with varying concentrations of SM or SB (1.0, 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 mg/ml) in combination with 800 μM MMS and subsequently incubated for 3 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 in RPMI medium containing 15% (v/v) fetal calf serum. The positive (MMS) and negative (DMSO) control groups were included. The experiment was performed in triplicate. The MMS concentration of 800 μM used in the present study was selected based on its previously demonstrated effectiveness in inducing DNA damage [17].

2.3. Comet Assay

The alkaline version of the comet assay was performed according to the protocol described by Singh and coworkers [18] with slight modifications. For antigenotoxicity evaluation, cells were treated with SM and SB, concomitant with the positive control, in order to verify the possible reduction of DNA damage caused by MMS. Briefly, after cell treatment, slides coated with normal melting point agarose (1.5%) were added with a mixture containing 15 μl of blood and 130 μl of low melting point agarose (0.5%) and incubated at 37°C. The mixture was spread on the slides with coverslips and placed in a cold chamber. Afterwards, the coverslips were carefully removed, and the slides were immersed in lysis solution protected from light (1% Triton X-100, 10% DMSO, 2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA-Na2, and 10 mM Tris) at 4°C for 4 h. Subsequently, the slides were incubated with freshly prepared alkaline solution buffer (300 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA, pH > 13) at 4°C for 20 min to unwind the DNA. Samples were then subjected to electrophoresis in the same buffer at 1 V/cm and the current of 300 mA for 30 min in the dark. After electrophoresis, the slides were placed on a staining tray, covered with neutralizing buffer (0.4 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), and kept in the dark for 5 min. For analysis, the slides were stained with 20 μl of ethidium bromide solution (0.02 mg/ml) and covered with a cover slip. A total of 50 nucleoids were analyzed per slide, corresponding to 100 nucleoids per sample.

The analysis was performed on a fluorescence microscopy system Axioplan-Imaging® (Carl Zeiss AG, Germany) using the Isis software with an excitation filter of 510-560 nm and a barrier filter of 590 nm under 20× magnification. To assess genomic damage, we used the TriTek Comet ScoreTM software (version 1.5), in which pixels intensities are used to estimate the degree of genomic damage and are given as arbitrary units. The nucleoids with completely fragmented heads were not included in the analysis.

From the 17 parameters provided by the software, we selected the percentage of DNA in the tail for assessing DNA damage. This parameter has been proposed by several authors to be the most useful parameter because it provides a quantitative measure of DNA damage (from 0 to 100%) [19].

2.4. Calculation of DNA Damage Reduction Percentage in Comet Test

For antigenotoxicity assessment, the percentage of reduction in MMS-induced damage by SM and SB was calculated according to Waters et al., 1990 [20], using the following formula:

| (1) |

where A corresponds to the DNA damage observed following treatment with MMS (positive control), B represents the group treated with SM or SB plus MMS, and C represents the negative control.

2.5. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

After treatment, human blood samples were transferred to tubes provided by GeneJET™ Whole Blood RNA Purification Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA). RNA extraction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Afterwards, the final RNA concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer NanoVuePlusTM (GE Healthcare, USA). RNA purity and integrity were assessed via 3% agarose gel electrophoresis. To ensure the purity of the RNA, the A260/A230 and A260/A280 absorbance ratios were evaluated. cDNA synthesis was performed using 1 μg of total RNA in a 10 μL sample volume using RT2 First Strand Kit® (PreAnalytix QIAGEN/BD Company, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer. Amplified cDNA was stored at -20°C.

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Design and Test

Customized qRT-PCR assay was performed using 96-well-plates. We analyzed five target genes (ETV6, PTEN, ABL1, BAX, and BCL2) using GAPDH as reference gene. In addition, the plates contained a genomic DNA control, a reverse-transcription control, and a positive PCR control.

The qRT-PCR using cDNA derived from treated human whole blood cells was performed using the RT2 SYBR Green Master Mix Kit® (PreAnalytix QIAGEN/BD Company, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Array-based qRT-PCR analysis was performed in 28 μL reaction volumes containing 1 μL of cDNA and 14 μL of RT2 SYBR Green Master Mix. Subsequently, 25 μL of PCR mix was added to each well of the RT2 Profiler PCR Array. Reactions were run on Bio-Rad's IQ5 real-time thermal cycler using the following cycling conditions: 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C; and 1 min at 60°C. The melting curve was performed as follows: 1 cycle of 1 min at 95°C, 2 min at 65°C, and 2 min at 65°C for 95°C. Results were obtained using iQ5® Optical System software version 2.1 and exported using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA). Gene expression analysis was carried out using the comparative ΔΔCt method.

The cycle threshold (Ct) values were exported to the PCR Array Data Analysis Web Portal (http://dataanalysis.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php). First, gene expression levels for each sample were normalized against those of the reference gene GAPDH (ΔCt). Ct data was used as an input, and the web-based software will automatically perform quantification using the ΔΔCt method (using positive control MMS treatment as standard sample). The fold change was calculated for each gene for all group samples.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For the comet assay, treatment and control groups were analyzed by performing one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5.0.

For gene expression analysis via qRT-PCR, gene expression levels corresponding to each cotreatment (positive control + silymarin or silibinin) were compared relative to the positive control (MMS) by performing the Student's t-test. The fold change values were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. A fold change > 2.0 or P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Modulation of MMS-Induced DNA Damage by Silymarin and Silibinin

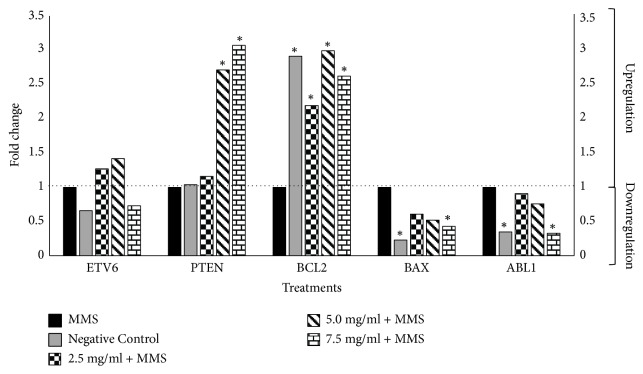

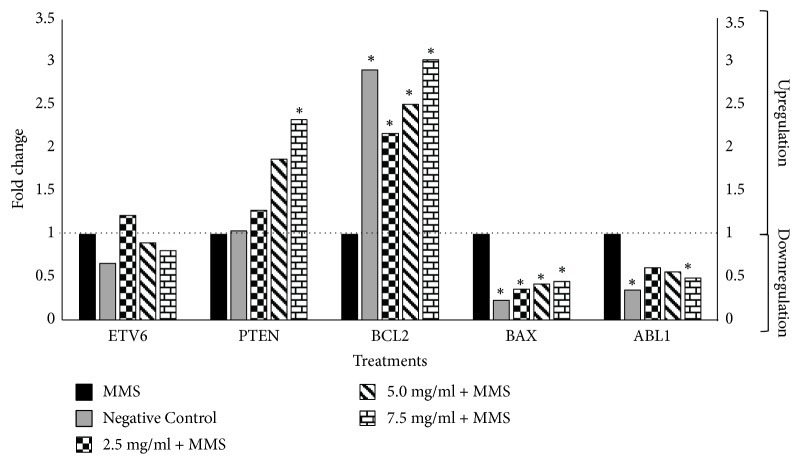

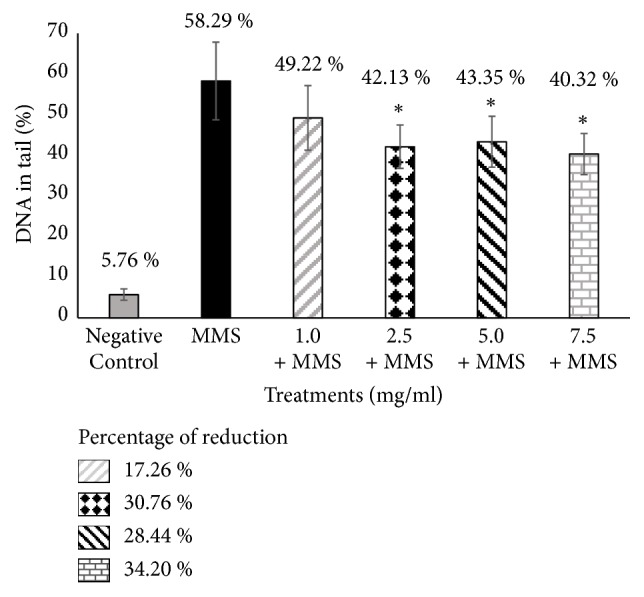

Assessment of the antigenotoxicity of SM and SB via the alkaline comet assay demonstrated reduced DNA damage (% DNA in tail) in cells cotreated with SM or SB and MMS relative to cells treated with the positive control MMS alone (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Evaluation of the antigenotoxic effects of silymarin by comet assay. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Percentage reduction in MMS-induced damage by SM. Negative control: 100 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) + sterile distilled water (1:1). Positive control: methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (800 µM). ∗ P < 0.05 versus MMS.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the antigenotoxic effects of silibinin by the comet assay. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Percentage reduction in MMS-induced damage by SB. Negative control: 100 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) + sterile distilled water (1:1). Positive control: methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (800 µM). ∗ P < 0.05 versus MMS.

Treatment with the standardized extract (SM) significantly reduced DNA damage for all tested concentrations of the compound when combined with MMS relative to treatment with MMS alone. SB, the major active constituent of SM, also exerted significant protective effect against DNA damage induced by the genotoxic agent MMS, except at a lower concentration (1.0 mg/ml) (Figures 1 and 2). The percentage of DNA in tail ranged from 47.46% to 38.04% for SM with MMS and 49.22% to 40.32% for SB with MMS. The percent reduction in DNA damage ranged from 20.61% to 38.54% for SM with MMS and 17.26% to 34.20% for SB with MMS when compared to treatment with MMS alone (58.29% DNA in tail).

3.2. Effects of Silymarin and Silibinin in Combination with MMS on Gene Expression in Human Blood Cells

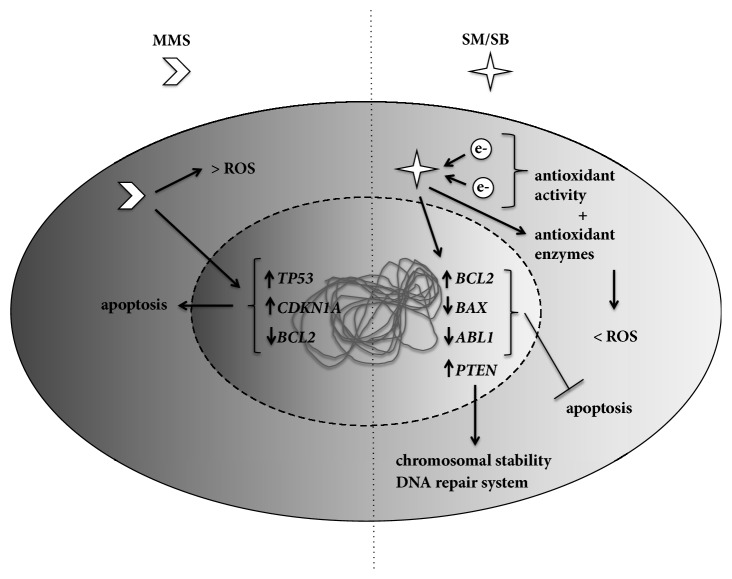

We evaluated the expression levels of the following five genes associated with DNA damage, carcinogenesis, and/or chemoprevention mechanisms: the tumor suppressors ETV6 and PTEN, the cell death regulators BCL2 and BAX (anti- and proapoptotic, respectively), and the protooncogene ABL1.

Expression levels of the tumor suppressor ETV6 gene (Figures 3 and 4) were not significantly altered in all samples treated with varying concentrations of SM + MMS or SB + MMS relative to those treated with MMS alone. However, results showed that the expression levels of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN were significantly upregulated following cotreatment with high SM concentrations (5.0 and 7.5 mg/ml) and the highest SB concentration (7.5 mg/ml), corresponding to fold change values of 2.71, 3.07, and 2.33, respectively (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Effects of combined treatment with MMS and silymarin on gene expression relative to MMS alone. Positive control: methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (800 µM). Negative control: 100 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) + sterile distilled water (1:1). Expression values greater than one indicate an upregulation, while expression values less than one indicate downregulation in the test sample relative to the positive control. ∗ P < 0.05 versus MMS.

Figure 4.

Effects of combined treatment with MMS and silibinin on gene expression relative to MMS alone. Positive control: methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (800 µM). Negative control: 100 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) + sterile distilled water (1:1). Expression values greater than one indicate upregulation, while expression values less than one indicate downregulation in the test sample relative to the positive control. ∗ P < 0.05 versus MMS.

Treatment with SM and SB at all concentrations was found to upregulate the expression of the antiapoptotic gene BCL2 up to threefold relative to the positive control, similar to the expression values obtained for the negative control. In addition, expression of the proapoptotic gene BAX was significantly downregulated following treatment with SM at the highest concentration and SB at all tested concentrations (Figures 3 and 4).

Furthermore, results demonstrated that the expression of ABL1, an apoptosis promoter and cell growth inhibitor gene, was significantly downregulated when human whole blood cells were treated with the highest concentration of SB or SM (7.5 mg/ml) (Figures 3 and 4).

4. Discussion

Many antioxidants are known to inhibit DNA damage by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are generated inside the cell [21]. Several plant species have been reported as reliable sources of antioxidants, and multiple studies have demonstrated that plant compounds promote genomic stability through various mechanisms [11–13, 22]. Silymarin (SM) and silibinin (SB) are known to exhibit strong antioxidant activities [5], and their protective effects against ROS have been demonstrated using different cell types, including mouse lymphocytes and human platelets [16, 23–25]. Furthermore, treatment with SM and SB was found to enhance the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, including glutathione peroxidase [26], which in turn inhibits ROS production. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the antigenotoxic activities of SM and SB using the comet assay and to assess their effects on the expression pattern of genes associated with carcinogenesis and chemopreventive processes.

To evaluate the chemopreventive effects of SB and SM on the DNA, human whole blood cells were treated with SB or SM in combination with methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). MMS is an alkylating agent that induces damage to genetic material and forms monoadducts with the nucleophilic centers of DNA [27]. Damage to the genetic material is highly associated with enhanced ROS production, as well as methylation at the N-7 position of guanine (N7MeG), at the N-3 position of adenine (N3MeA), and at the O-6 position of guanine (O6MeG) [14, 15]. A previous study on human lymphocytes and sperm cells indicated that MMS exposure promoted DNA damage based on the comet assay (increased Olive Tail Moment and % DNA in tail) and triggered the apoptotic response by upregulating the expression of TP53 and CDKN1A and downregulating the expression of BCL2 [28].

Our results showed that both the complex (SM extract) and its main active constituent (SB), cotreated with MMS, exerted protective effects by reducing the amount of DNA in the comet tail in 42.49% and 34.20% respectively, when compared to positive control (MMS). Previous studies also demonstrated the protective effects of SM and SB. In particular, SM and SB significantly decreased point mutations based on the Ames test and reduced the proportion of micronucleated polychromatic erythrocytes based on the mice bone marrow assay [29]. Furthermore, SB was demonstrated to exert protective effects against γ-radiation-induced strand breaks in plasmid DNA, reduce DNA damage and micronuclei formation in human lymphocytes and rat leukocytes, and reduce mouse mortality and DNA damage in blood leukocytes following whole-body γ-exposure in mice [16, 30].

In addition, the current findings revealed that the extract complex (SM) exerted slightly stronger antigenotoxic activity compared to the primary active constituent (SB); however, the observed difference was not statistically significant. Our current findings were consistent with those of a previous study, which demonstrated that “high purity” milk thistle extracts exerted weaker antioxidant activity relative to the complex extract [29]. The above results suggest that the SM extract contains compounds other than SB that contribute to the antioxidant potential of SM. The final response of a treatment with a plant extract is a result of synergistic, antagonistic, and other interactive effects among plant biologically active compounds present in the extract and the cell machinery [31].

To elucidate the effects of cotreatment with MMS and SM or SB, we evaluated the expression levels of five genes that are specifically known to mediate chemoprevention and response to DNA damage.

The tumor suppressor gene ETV6 (ets variant gene 6) encodes a protein that functions as a transcriptional regulator by binding to a specific DNA sequence. Our current findings revealed that the ETV6 expression patterns were not significantly altered following treatment with any tested concentration of SM and SB when compared to the positive control, indicating that SM and SB did not influence ETV6 expression.

The PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) gene is a tumor suppressor involved in cell migration and proliferation inhibition and participates in the modulation of cell growth and apoptosis. The essential role of nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal stability has been demonstrated in both mouse and human systems [32]. According to Yin and Shen [33], nuclear PTEN may utilize two mechanisms to maintain chromosome integrity. First, PTEN interacts with centromeres and maintains their stability through its C2 domain. Second, PTEN may be necessary for DNA repair, since loss of PTEN leads to a high proportion of double-strand breaks. Our results demonstrated significant upregulation of PTEN expression following treatment with high concentrations of SM or SB, what could contribute to explain the anticytotoxic and antigenotoxic properties of SM and SB. Also, these data allow us to infer that these protective effects may also help in the regulation and preservation of DNA in cells that are in the active process of cell division as shown in a study using mice bone marrow cells, in which SM and SB reduced the frequency of micronucleated cells [29].

The Bcl-2 family comprises proapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins. BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma protein 2) is associated with programmed cell death inhibition in various cell types. The antiapoptotic function of BCL2 appears to be mediated by its ability to heterodimerize with other Bcl-2 family members, especially BAX (BCL-2 associated X protein). BCL2 prevents the oligomerization of BAX, which normally causes the release of several mitochondrial apoptogenic molecules [34]. Our results showed that treatment with SM or SB significantly upregulated BCL2 expression at all tested concentrations. MMS is known to downregulate BCL2 expression [15]; however, SM and SB can upregulate the expression of this survival factor by interacting with the BCL2 promoter, which harbors several putative responsive sites, or through an indirect pathway. In addition, treatment with SM or SB significantly downregulated the expression of BAX, thereby suggesting that SM and SB can prevent apoptosis and act as chemoprotective agents. Previous studies demonstrated the modulatory effects of SM and SB on cell survival and apoptosis via interference with the expression of cell cycle regulators and proteins involved in apoptosis [6, 35–37].

The ABL1 gene is a protooncogene that encodes a protein tyrosine kinase known to be involved in various cellular processes, including cell division, adhesion, differentiation, and stress response. Nuclear ABL proteins modulate cellular responses induced by DNA damage and are known to participate in cell growth inhibition and apoptosis promotion [38]. In the present study, treatment with the highest tested concentration of SM and SB was found to significantly downregulate ABL1 expression relative to treatment with MMS alone, although the lower SM and SB concentrations did not significantly alter ABL1 expression patterns. The observed downregulation of ABL1 expression can be associated with the repair of DNA lesions.

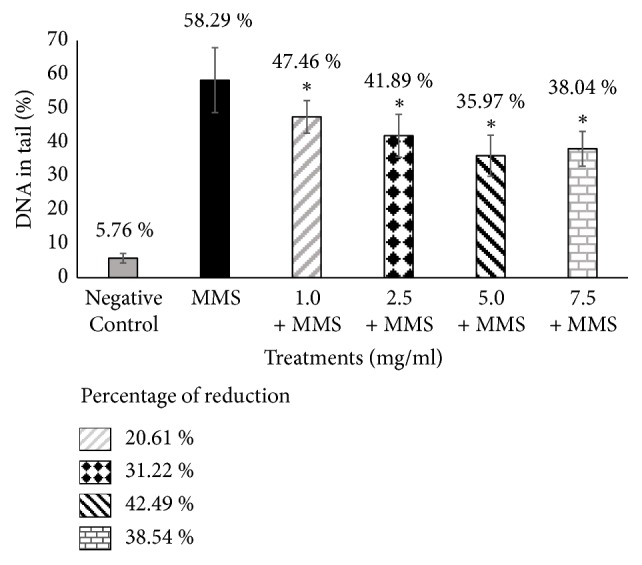

The decrease in DNA damage and the modulation of gene expression to protect cells against lesions suggested the roles of SM and SB in the DNA repair system (Figure 5). Thus, the protective effects of both compounds highlighted their potential clinical use as complementary treatment for cancer patients in combination with established treatments to prevent or reduce the toxicity induced by chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. However, further studies are required to investigate the effects of SM and SB on the DNA repair system.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the effects of silymarin and silibinin on chemopreventive mechanisms. While methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) is highly associated with enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [14] and apoptotic response [15], silymarin (SM) and silibinin (SB) exhibit strong antioxidant activities [5, 16] and can prevent apoptosis and influence the genomic stability and the DNA repair system.

Acknowledgments

Flávio Fernandes Veloso Borges was supported with a scholarship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Elisa Flávia Luiz Cardoso Bailão was supported by Universidade Estadual de Goiás with fellowships at the program PROBIP (Scientific Production Support Program). The authors also thank Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Goiás (FAPEG) for the financial support.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Disclosure

This work is part of a thesis made by the author Flávio Fernandes Veloso Borges [39].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Robinson M. M., Zhang X. The World Medicines Situation 2011 Traditional Medicines: Global Situation, Issues and Challenges. World Heal Organ; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.AbouZid S. F., Chen S.-N., Pauli G. F. Silymarin content in Silybum marianum populations growing in Egypt. Industrial Crops and Products. 2016;83:729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur M., Agarwal R. Silymarin and epithelial cancer chemoprevention: How close we are to bedside? Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;224(3):350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraschini F., Demartini G., Esposti D. Pharmacology of silymarin. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2002;22(1):51–65. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200222010-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köksal E., Gülçin I., Beyza S., Sarikaya Ö., Bursal E. In vitro antioxidant activity of silymarin. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;24(2):395–405. doi: 10.1080/14756360802188081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal R., Agarwal C., Ichikawa H., Singh R. P., Aggarwal B. B. Anticancer potential of silymarin: from bench to bed side. Anticancer Reseach. 2006;26(6):4457–4498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radko L., Cybulski W. Application of silymarin in human and animal medicine. J Pre-Clinical Clin Res. 2007;1:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surh Y. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3(10):768–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathers J. C., Coxhead J. M., Tyson J. Nutrition and DNA repair - Potential molecular mechanisms of action. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7(5):425–431. doi: 10.2174/156800907781386588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guarnieri S., Loft S., Riso P., et al. DNA repair phenotype and dietary antioxidant supplementation. British Journal of Nutrition. 2008;99(5):1018–1024. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507842796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotecha R., Takami A., Espinoza J. L. Dietary phytochemicals and cancer chemoprevention: a review of the clinical evidence. Oncotarget . 2016;7(32):52517–52529. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yates T. J., Lopez L. E., Lokeshwar S. D., et al. Dietary Supplement 4-Methylumbelliferone: An Effective Chemopreventive and Therapeutic Agent for Prostate Cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015;107(7) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv085.djv085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahey J. W., Kensler T. W. Role of dietary supplements/nutraceuticals in chemoprevention through induction of cytoprotective enzymes. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2007;20(4):572–576. doi: 10.1021/tx7000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu D., Calvo J. A., Samson L. D. Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12(2):104–120. doi: 10.1038/nrc3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitanovic A., Walther T., Loret M. O., et al. Metabolic response to MMS-mediated DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is dependent on the glucose concentration in the medium. FEMS Yeast Research. 2009;9(4):535–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bijak M., Synowiec E., Sitarek P., Sliwiński T., Saluk-Bijak J. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of flavonolignans in different cellular models. Nutrients. 2017;9(12) doi: 10.3390/nu9121356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y., Shan S., Chi L., et al. Methyl methanesulfonate induces necroptosis in human lung adenoma A549 cells through the PIG-3-reactive oxygen species pathway. Tumor Biology. 2016;37(3):3785–3795. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3531-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh N. P., McCoy M. T., Tice R. R., Schneider E. L. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1988;175(1):184–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins A., Koppen G., Valdiglesias V., et al. The comet assay as a tool for human biomonitoring studies: The ComNet Project. Mutation Research - Reviews in Mutation Research. 2014;759(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waters M. D., Brady A. L., Stack H. F., Brockman H. E. Antimutagenicity profiles for some model compounds. Mutation Research/Reviews in Genetic Toxicology. 1990;238(1):57–85. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(90)90039-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svobodová A., Zdařilová A., Mališková J., Mikulková H., Walterová D., Vostalová J. Attenuation of UVA-induced damage to human keratinocytes by silymarin. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2007;46(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson L. R. Role of plant polyphenols in genomic stability. Mutation Research. 2001;475(1-2):89–111. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chlopčíková Š., Psotová J., Miketová P., Šimánek V. Chemoprotective Effect of Plant Phenolics against Anthracycline-induced Toxicity on Rat Cardiomyocytes. Part I. Silymarin and its Flavonolignans. Phytotherapy Research. 2004;18(2):107–110. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pietrangelo A., Borella F., Casalgrandi G., et al. Antioxidant activity of silybin in vivo during long-term iron overload in rats. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(6):1941–1949. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90762-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiwari P., Kumar A., Ali M., Mishra K. Radioprotection of plasmid and cellular DNA and Swiss mice by silibinin. Mutation Research - Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis. 2010;695(1-2):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao J., Lahiri-Chatterjee M., Sharma Y., Agarwal R. Inhibitory effect of a flavonoid antioxidant silymarin on benzoyl peroxide-induced tumor promotion, oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in SENCAR mouse skin. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(4):811–816. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beranek D. T. Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutation Research - Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 1990;231(1):11–30. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habas K., Najafzadeh M., Baumgartner A., Brinkworth M. H., Anderson D. An evaluation of DNA damage in human lymphocytes and sperm exposed to methyl methanesulfonate involving the regulation pathways associated with apoptosis. Chemosphere. 2017;185:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borges F. F. V., Silva C. R., Véras J. H., Cardoso C. G., da Cruz A. D., Chen L. C. Antimutagenic, Antigenotoxic, and Anticytotoxic Activities of Silybum Marianum [L.] Gaertn Assessed by the Salmonella Mutagenicity Assay (Ames Test) and the Micronucleus Test in Mice Bone Marrow. Nutrition and Cancer. 2016;68(5):848–855. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2016.1180414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toğay V. A., Sevimli T. S., Sevimli M., Çelik D. A., Özçelik N. DNA damage in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes; protective effect of silibinin. Mutation Research - Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis. 2018;825:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walle T. Absorption and metabolism of flavonoids. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2004;36(7):829–837. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen W. H., Balajee A. S., Wang J., et al. Essential Role for Nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 2007;128(1):157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin Y., Shen W. H. PTEN: a new guardian of the genome. Oncogene. 2008;27(41):5443–5453. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Youle R. J., Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2008;9(1):47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai Z.-L., Tay V., Guo S.-Z., Ren J., Shu M.-G. Silibinin Induced Human Glioblastoma Cell Apoptosis Concomitant with Autophagy through Simultaneous Inhibition of mTOR and YAP. BioMed Research International. 2018;2018:10. doi: 10.1155/2018/6165192.6165192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui H., Li T., Guo H., et al. Silymarin-mediated regulation of the cell cycle and DNA damage response exerts antitumor activity in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology Letters. 2018;15(1):885–892. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haddadi R., Nayebi A. M., Eyvari Brooshghalan S. Silymarin prevents apoptosis through inhibiting the Bax/caspase-3 expression and suppresses toll like receptor-4 pathway in the SNc of 6-OHDA intoxicated rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2018;104:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panjarian S., Iacob R. E., Chen S., Engen J. R., Smithgall T. E. Structure and dynamic regulation of abl kinases. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(8):5443–5450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.438382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borges F. F. V. Atividades antimutagênica, antigenotóxica e anticitotóxica de Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn e sua influência na expressão de genes de resposta a danos no DNA [Ph.D. thesis] Universidade Federal de Goiás; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.