Abstract

Background

Overprescription of antibiotics for lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) in children is common, partly due to diagnostic uncertainty, in which case the addition of point-of-care (POC) C-reactive protein (CRP) testing can be of aid.

Aim

To assess whether use of POC CRP by the GP reduces antibiotic prescriptions in children with suspected non-serious LRTI.

Design & setting

An open, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial in daytime general practice and out-of-hours services.

Method

Children between 3 months and 12 years of age with acute cough and fever were included and randomised to either use of POC CRP or usual care. Antibiotic prescription rates were measured and compared between groups using generalising estimating equations.

Results

There was no statistically significant reduction in antibiotic prescriptions in the GP use of CRP group (30.9% versus 39.4%; odds ratio [OR] 0.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.29 to 1.23). Only the estimated severity of illness was related to antibiotic prescription. Forty-six per cent of children had POC CRP levels <10mg/L.

Conclusion

It is still uncertain whether POC CRP measurement in children with non-serious respiratory tract infection presenting to general practice can reduce the prescription of antibiotics. Until new research provides further evidence, POC CRP measurement in these children is not recommended.

How this fits in

POC CRP testing has added value in the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults, and has proven to safely reduce antibiotic prescriptions in general practice. In children, POC CRP testing has proven valuable in ruling out serious infections, but the effect of its use by GPs on the prescription of antibiotics was not known. There was no significant reduction in antibiotic prescriptions when GPs used POC CRP testing in children with suspected non-serious LRTI.

Introduction

Acute respiratory tract infections are the most common diagnoses in children in primary care.1,2 Childhood LRTIs include acute bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia. Pneumonia is a rare but serious condition and should be treated with antibiotics because of the difficulty in distinguishing viral from bacterial causes,3,4 whereas bronchitis and bronchiolitis are more common and usually self-limiting illnesses.5–7

Despite being of value in only a minority of children with LRTI, and contrary to recommendations in national guidelines,4 antibiotics are frequently prescribed in general practice in the Netherlands, with prescription rates varying between 56 and 70%.1,8,9 Diagnostic uncertainty, parental worries and expectations, or the GP’s anticipation of these, are important drivers of antibiotic prescriptions.8,10,11 Even in a low prescribing country like the Netherlands, 48–63% of antibiotic prescriptions are thought to be inappropriate.10,12 This is harmful as antibiotics cause side effects,12 increase re-consultation rates,13 and contribute to antimicrobial resistance. Repeated use of antibiotics increases antimicrobial resistance in communities but also in individuals,14–15 making it important to correctly identify children who need antibiotics, but equally important to protect those who will not benefit.

Although CRP levels do not allow differentiation between bacterial or viral origin of an infection in adults or children, they are proxy for the disease severity.16–18 In adults, POC CRP has added value in the diagnosis of pneumonia19–21 and safely reduces antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory tract infections in primary care.22 Following this evidence, national guidelines on acute cough recommend POC CRP testing for adults in case of diagnostic uncertainty,4 similar to the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline on pneumonia in adults.23 More than half of all Dutch GPs now have access to POC CRP testing, in daytime practice as well as at out-of-hours services.24–25

Although POC CRP is also of diagnostic value for diagnosing pneumonia in children26 and useful in ruling out serious infection in children,27 its effect on antibiotic prescribing for children with symptoms of LRTI is unclear. In this study, it was assessed whether POC CRP testing in children with a suspected non-serious LRTI reduces antibiotic prescribing compared to usual care without CRP testing.

Method

This is a pragmatic, open, randomised controlled two-arm trial in primary care.

Participants and setting

Between December 2013 and May 2016, children aged between 3 months and 12 years were recruited in 28 daytime general practices across three different regions in the Netherlands. Due to slow recruitment rates, children were additionally recruited at four out-of-hours services between November 2015 and May 2016. Children were eligible for inclusion if they had acute cough, reported fever, and were suspected of having a non-serious LRTI by the treating GP. Children who were judged as severely ill or highly suspect of pneumonia were excluded (Box 1). Parents provided written informed consent.

Box 1. Eligibility criteria.

| Inclusion (all criteria must be present) | Exclusion (any presence of) |

|---|---|

| Suspicion of lower respiratory tract infection | Impaired immunity |

| Age 3 months–12 years | Severe pulmonary disease |

| Acute cough <21 days | Serious congenital defects |

| Reported fever >38 °C, <5 days | Use of systemic antibiotics and/or corticosteroids in past 4 weeks |

| Judged severely ill by the GP based on symptoms and signs | |

| Highly suspected of having pneumonia by the GP | |

| Referral to specialist or emergency department deemed necessary by GP |

Randomisation

Daytime general practices were cluster randomised per practice, to avoid contamination. Furthermore, it was that expected GPs might experience a learning effect from conducting CRP tests. By linking CRP levels to apparent severity of illness, this could have affected prescribing in the control group. Block randomisation stratified by region and practice type (academic versus non-academic) was used.28

Arguments for cluster randomisation were not applicable to an out-of-hours service, where GPs participated in this study during one shift, and included two children at most. Therefore, children recruited at out-of-hours services were individually randomised using sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes (SNOSE).29 The SNOSE piles were prepared by a member of the research team, using permuted block randomisation. After the treating GP checked eligibility, an onsite research assistant, blinded to the clinical evaluation of the child, opened the envelope.

Intervention

For children in the intervention group, a POC CRP test was performed after clinical assessment by the treating GP. In the control group GPs were advised not to use POC CRP, and treatment decisions were based on clinical assessment as usual.

CRP was measured using an Afinion™ POC testing device (Alere Technologies AS, Oslo, Norway), with a measurement range between 5 and 160 mg/L, and reliable for use in children.30 The result of the test is available within 4 minutes, requiring 1.5 μL of blood obtained via finger prick.

GPs were not provided with strict decision rules based on CRP levels, but were given the following guidance:

POC CRP levels should be interpreted in combination with symptoms and signs.

CRP levels <10mg/L make pneumonia less likely, but should not be used to exclude pneumonia when the GP finds the child ill, or when duration of symptoms is <6 hours.

CRP levels >100mg/L make pneumonia much more likely, however, such levels can also be caused by viral infections.

Between 10mg/L and 100mg/L, the likelihood of pneumonia increases with increasing CRP levels.

All management decisions including the use of other diagnostic tests and treatment were left to the GP’s discretion.

Data collection

At baseline, GPs recorded the child’s temperature and assessed illness severity on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). At the end of consultation they registered their working diagnosis and treatment plan. Three months after inclusion, children's medical records were reviewed to collect data on secondary outcomes.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was antibiotic prescribing at the index consultation. Secondary outcomes were re-consultation and antibiotic prescribing during the same illness episode, consultation for a new episode of any respiratory tract infection within 3 months of the index consultation, and antibiotic prescriptions at these consultations.

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was based on the expectation that POC CRP testing would reduce antibiotic prescribing by at least 20%, from 70% to 50%. To detect such a difference with 80% power and two-sided 5% significance, and considering a cluster size of 16 and an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.06, a total of 354 patients were required. After expanding recruitment to the out-of-hours services the sample size calculations were not altered as a cluster effect is not present for the children individually randomised at the out-of-hours services and this would most likely lead to a reduction in the number of children needed.

Statistical analysis

For the primary outcome, data were analysed with an intention-to-treat approach using general estimating equations to account for cluster effects and the baseline characteristics age, estimated illness severity, inclusion at out-of-hours service, and index of deprivation based on postal code. Children with missing outcomes were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, the primary outcome was analysed using a per protocol approach. Secondary outcomes are analysed using generalised estimating equations to account for cluster effects. Analysis was done using SPSS (version 21).

Results

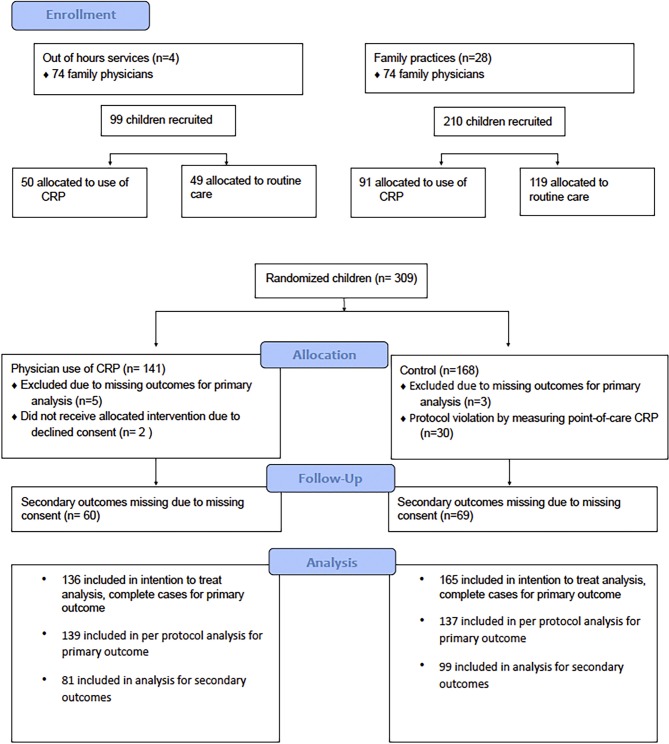

Three hundred and nine children were recruited by 148 GPs (Figure 1). Eight children were excluded due to missing age (n = 7) or severity of illness score (n =1) at baseline. Characteristics of children in both groups were similar regarding age, sex, symptoms, fever, and estimated illness severity. In the control group, more children had a low social economic status (Table 1). GPs noted bronchitis as their final diagnosis in 21.3% of the children, and pneumonia in 13.3%. All diagnoses are listed in Table 2. Based on estimated illness severity, children presenting to the out-of-hours service were not more severely ill than children presenting to daytime general practice (mean VAS score 3.7 versus 4.0; P = 0.2).

Figure 1. Trial profile.

Table 1. Characteristics of randomised children at baseline.

| GP use of CRP (N = 136) | Control (N = 165) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 3 (0–11) | 2 (0–11) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 65 (47.8) | 81 (49.1) |

| Abnormalities at auscultation, n (%) | 71 (50.4) | 83 (49.4) |

| Signs of otitis media acuta, n (%) | 13 (9.2) | 23 (13.7) |

| Signs of tonsillitis, n (%) | 17 (12.1) | 18 (10.7) |

| Mean temperature, °C | 38.2 | 38.0 |

| Estimated severity of illness by GP, range (mean) | 0.3–8.5 (4.0) | 0–8.0 (3.8) |

| Recruited at out-of-hours service | 49 (36.0) | 49 (29.7) |

| Low social economic status | 4 (2.9) | 17 (10.3) |

Table 2. Recorded diagnosis by GP after medical history, physical examination, and point-of-care C-reactive protein if applicable (N = 301).

| Diagnosis | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 93 | 30.9 |

| Bronchitis | 64 | 21.3 |

| Pneumonia | 40 | 13.3 |

| Cough | 27 | 9 |

| Viral respiratory tract infection | 14 | 4.7 |

| Influenza | 12 | 4 |

| Fever | 11 | 3.7 |

| Bronchial hyperreactivity | 9 | 3 |

| Otitis media acuta | 9 | 3 |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 7 | 2.3 |

| Respiratory tract infection, not specified | 7 | 2.3 |

| Acute laryngitis or tracheitis | 1 | 0.3 |

| Otitis media with effusion | 1 | 0.3 |

| No diagnosis noted | 6 | 2 |

Antibiotic prescription and re-consultations

GPs in the CRP group prescribed antibiotics to 30.9% of the children compared to 39.4% in the control group (OR 0.6; 95% CI = 0.30 to 1.24). The only factor significantly related to the prescription of antibiotics was the estimated illness severity (OR 1.44; 95% CI = 1.26 to 1.66).

POC CRP was not measured in two children in the intervention group (1.4%), and in the control group point-of care CRP was measured 30 times (18.2%), in violation of protocol (Figure 1). A per protocol analysis, excluding these 32 children, showed no significant difference in antibiotic prescription rates at the index consultation.

Due to missing consent of the parents for follow-up, follow-up data were only available for 180 children (58% of total, 81/141 children [57%] in the intervention group and 99/168 children [59%] in control group). Children in both groups had similar rates of re-consultations within the same episode of illness (33% versus 34%; OR 0.95; 95% CI = 0.46 to 1.99) and antibiotic prescriptions during these consultations (7% versus 8%; OR 0.94; 95% CI = 0.33 to 2.63). In the next 3 months, 16% of children in the CRP group consulted their GP for respiratory tract illness, compared to 29% in the control group (OR 0.61; 95% CI = 0.32 to 1.17) (Table 3). One child in the control group was admitted to hospital directly after inclusion.

Table 3. Effects of CRP testing on secondary outcomes.

| GP use of CRP (N = 81) n (%) |

Control (N = 99) n (%) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Re-consultation for baseline episode of illness | 27 (33) | 34 (34) | 0.95 (0.46 to1.99) |

| Antibiotics for baseline episode of illness | 6 (7) | 8 (8) | 0.94 (0.33 to 2.63) |

| Non-urgent referral to secondary care for baseline episode of illness | 3 (4) | 5 (5) | 0.93 (0.18 to 4.86) |

| Consultation for new episode of RTI within 3 months | 13 (16) | 29 (29) | 0.61 (0.32 to 1.17) |

| Antibiotics for new episode of RTI within 3 months | 2 (2) | 7 (7) | 0.34 (0.08 to 1.39) |

| Non-urgent referral to secondary care for new episode of RTI | 3 (4) | 7 (7) | 0.54 (0.10 to 2.79) |

CI = confidence interval. RTI = respiratory tract infection.

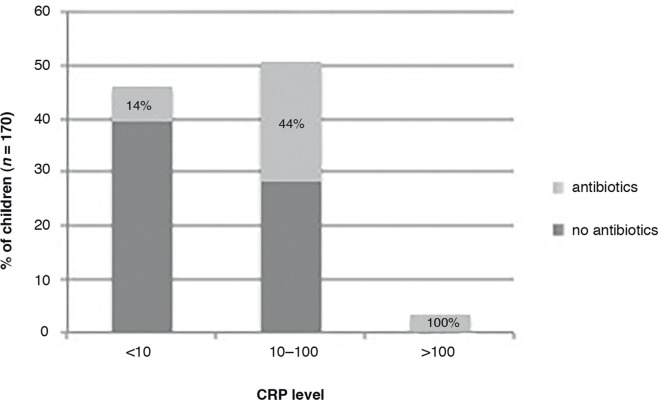

CRP levels and antibiotic prescriptions

CRP levels ranged from <5 to 200 mg/L, with 46% of children having a CRP level <10 mg/L, 51% 10–100 mg/L, and 4% >100 mg/L. Control children in whom CRP was measured were not more seriously ill than other control children (mean illness severity 3.8 in both groups; P = 0.9), and their mean CRP level was not significantly different from the mean CRP level in children in the intervention group (mean 22.5 versus 24.9; P = 0.72).

Children were more likely to get an antibiotic prescription with increasing CRP level, ranging from 14% in children with a CRP level <10 mg/L to more than 50% in children with a CRP level >40 mg/L (Figure 2).

Figure 2. CRP levels and antibiotic prescriptions.

Discussion

Summary

In this open, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial in primary care, there was no significant effect on antibiotic prescribing for children with non-serious respiratory tract infection when GPs used POC CRP: antibiotic prescribing was 30.9% in the CRP group versus 39.4% in the intervention group. Re-consultation and antibiotic prescriptions in the following 3 months also did not differ significantly.

Strengths and weaknesses

A pragmatic design was used, evaluating POC CRP testing in daytime general practices and out-of-hours services, making the results generalisable to routine general practice. The cluster design in daytime general practices aimed to minimise learning effects and contamination. Nevertheless, there were protocol violations in the control group, potentially diluting the effect of CRP. A per protocol analysis, however, did not find a significant effect.

Although a trend towards reduction in antibiotic prescriptions was observed, it was not possible to prove that this is statistically significant. This may in part be due to lack of power to detect this smaller than expected decrease. Antibiotic prescribing rates were lower than expected in both groups. Based on earlier studies in children with LRTI, the authors presumed an antibiotic prescription rate of 70% in the control group in the sample size calculation.1,9 This lower prescription rate may have been caused by the recruited patient mix, in particular by the inclusion of children with an upper respiratory tract infection in whom antibiotics are known to be prescribed less frequently.10–11,31 Although this study aimed to include children with LRTI and the inclusion criteria were designed accordingly, there is a discrepancy between these criteria and the GP’s reported diagnosis after complete assessment. Often a symptom-based diagnosis, or an upper respiratory tract infection was reported. The open character of this study, with the GP unblinded to the CRP level before noting a final diagnosis, might have influenced diagnostic labelling.

The study did not reach the planned sample size (309 out of 354 children), despite a prolonged recruitment period and addition of the out-of-hours services for recruitment. This may have further affected the power of the study, and a larger study is necessary to decide whether POC CRP can reduce antibiotic prescriptions. Although the study aimed for a large reduction in the prescription of antibiotics based on results from trials in adults,32 if a future study could confirm these results, a decrease of 8.5% in antibiotic prescriptions in this group of primary care patients could be considered clinically relevant, as in other studies with the same aim in adults.33–34

Data for analysis of secondary outcomes were available for 58% of the children. Quite low follow-up rates were the result of a need for obligatory double consent in the Netherlands, signed by both parents, to collect follow-up. This double consent proved difficult to obtain in general practice.35 There is no indication that loss to follow-up was related to any other factors.

Comparison with existing literature

CRP levels in this study correspond with reported levels in adults32 and children with respiratory infections.27,36 Most children had low CRP levels, as is expected in a primary care setting, because most children suffer from non-serious illnesses. In a recent Norwegian study in children with fever and/or respiratory symptoms presenting to out-of-hours services, antibiotics were prescribed to 13% of children with CRP levels <20 mg/L.37 In the current study, 14% of children with a CRP level <10 mg/L were prescribed antibiotics. As in the current study, a CRP level >20 mg/L was found to be a strong predictor for the prescription of antibiotics.

Implications for research and practice

It is still uncertain whether POC CRP can reduce antibiotic prescriptions for children with suspected non-serious LRTI. Future research should focus on this question.

Future research should also focus on the value that POC CRP potentially has in more correctly identifying the children in primary care that suffer from pneumonia, as current evidence shows no definite cut-off levels that are useful to rule in the child in need of antibiotic treatment. This could lead to uncertainty in management of children with intermediate to higher CRP levels.

More than half of children with a POC CRP level >40 mg/L in this study were prescribed antibiotics. CRP POC testing was introduced in primary care for adults with LRTI, to support decisions on antibiotic prescribing.22 This may have led GPs to consider elevated CRP levels as a proxy for bacterial infection automatically warranting antibiotics. However, CRP levels do not allow differentiation between bacterial or viral origin of infection, but are a proxy for the disease severity.16–18 Therefore, an elevated CRP level in children is a red flag for potential serious infection. This may require treatment with antibiotics, but should especially prompt the GP to ensure proper instruction of parents and careful safety-netting. Efforts should be made to educate GPs on the current evidence on the value of POC CRP for children. Further research is necessary to provide them with threshold-specific recommendations.

In this study, children with low CRP levels were prescribed antibiotics, although children who were judged as severely ill or highly suspected of having pneumonia were excluded, and despite evidence that CRP levels <5 mg/L can safely rule out serious infections requiring hospitalisation in children.27 Knowledge on the GPs’ reasoning behind these prescriptions, including possible non-medical reasons, might provide further insights to better target interventions for antibiotic stewardship.

In conclusion, it is still uncertain whether POC CRP measurement in children with non-serious respiratory tract infection presenting to general practice can reduce the prescription of antibiotics. Until further research provides more evidence, POC CRP measurement in children with non-serious respiratory tract infection is not recommended.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW grant number 837001008) and Alere Technologies AS. These funding bodies had no role in the design and conduct of the study, nor in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Further funding and logistic support by providing the reagents and equipment for CRP testing was given by two participating laboratories, SALTRO and Star Medical Diagnostic Center. Two of the authors are employed at SALTRO but the funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands, approved this study. Parents provided written informed consent for participation of all children in the study. The PRICE trial (Point-of-caRe C-reactive protein to assist In primary care management of Children with lower rEspiratory tract infection) was registered at the Netherlands National Trial Register (trial identifier NTR4399).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to the doctors, nurses, and patients from the participating general practices and out-of-hours services. They also thank the research assistants working at the out-of-hours services. Thanks also to Peter Zuithoff for advising on and aiding with the statistical analysis, Susan van Hemert for aiding with data management, and Annelies Verweij, Lianne van den Heuvel, and Nynke Koning for practical assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.van der Linden MW, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Schellevis F, et al. Tweede Nationale Studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk: het kind in de huisartspraktijk. (Second National Survey of morbidity and interventions in general practice: the child in general practice) Utrecht: NIVEL; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming DM, Smith GE, Charlton JR, et al. Impact of infections on primary care — greater than expected. Commun Dis Public Health. 2002;5(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccles S, Pincus C, Higgins B, et al. Diagnosis and management of community and hospital acquired pneumonia in adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g6722. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verlee L, Verheij TJ, Hopstaken RM, et al. [Summary of NHG practice guideline 'Acute cough'] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156(0):A4188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagakumar P, Doull I. Current therapy for bronchiolitis. Arch of Child. 2012;97(9):827–830. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SM, Smucny J, Fahey T. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2678–2679. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Florin TA, Plint AC, Zorc JJ. Viral bronchiolitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10065):211–224. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30951-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen AG, Sanders EA, Schilder AG, et al. Primary care management of respiratory tract infections in Dutch preschool children. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24(4):231–236. doi: 10.1080/02813430600830469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Deursen AM, Verheij TJ, Rovers MM, et al. Trends in primary-care consultations, comorbidities, and antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory infections in The Netherlands before implementation of pneumococcal vaccines for infants. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(5):823–834. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811001361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker AR, Verheij TJ, van der Velden AW. Inappropriate antibiotic prescription for respiratory tract indications: most prominent in adult patients. Fam Pract. 2015;32(4):cmv019–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elshout G, Kool M, Van der Wouden JC, et al. Antibiotic prescription in febrile children: a cohort study during out-of-hours primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(6):810–818. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.110310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clavenna A, Bonati M. Adverse drug reactions in childhood: a review of prospective studies and safety alerts. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(9):724–728. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.154377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, et al. Reattendance and complications in a randomised trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalising effect of prescribing antibiotics. BMJ. 1997;315(7104):350–352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7104.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gisselsson-Solen M, Hermansson A, Melhus Å. Individual-level effects of antibiotics on colonizing otitis pathogens in the nasopharynx. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;88:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryce A, Hay AD, Lane IF, et al. Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in paediatric urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli and association with routine use of antibiotics in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;352:i939. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flood RG, Badik J, Aronoff SC. The utility of serum C-reactive protein in differentiating bacterial from nonbacterial pneumonia in children: a meta-analysis of 1230 children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(2):95–99. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318157aced. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heiskanen-Kosma T, Korppi M. Serum C-reactive protein cannot differentiate bacterial and viral aetiology of community-acquired pneumonia in children in primary healthcare settings. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32(4):399–402. doi: 10.1080/003655400750044971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T, et al. Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d3082. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minnaard MC, de Groot JA, Hopstaken RM, et al. The added value of C-reactive protein measurement in diagnosing pneumonia in primary care: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ. 2016 doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopstaken RM, Muris JW, Knottnerus JA, et al. Contributions of symptoms, signs, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein to a diagnosis of pneumonia in acute lower respiratory tract infection. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(490):358–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Vugt SF, Broekhuizen BD, Lammens C, GRACE consortium. et al. Use of serum C reactive protein and procalcitonin concentrations in addition to symptoms and signs to predict pneumonia in patients presenting to primary care with acute cough: diagnostic study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aabenhus R, Jensen JU, Jorgensen KJ, et al. Biomarkers as point-of-care tests to guide prescription of antibiotics in patients with acute respiratory infections in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD010130. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010130.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Pneumonia: diagnosis and management of community and hospital acquired pneumonia in adults [NICE Guideline CG191] http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gc191. 2014 (accessed 26 Jun 2018). [PubMed]

- 24.Howick J, Cals JW, Jones C, et al. Current and future use of point-of-care tests in primary care: an international survey in Australia, Belgium, The Netherlands, the UK and the USA. BMJ Open. 2014;4(8):e005611. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schols AM, Stevens F, Zeijen CG, et al. Access to diagnostic tests during GP out-of-hours care: A cross-sectional study of all GP out-of-hours services in the Netherlands. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22(3):176–181. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2016.1189528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koster MJ, Broekhuizen BD, Minnaard MC, et al. Diagnostic properties of C-reactive protein for detecting pneumonia in children. Respir Med. 2013;107(7):1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verbakel JY, Lemiengre MB, De Burghgraeve T, et al. Should all acutely ill children in primary care be tested with point-of-care CRP: a cluster randomised trial. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0679-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbaniak GC, Plous S. Research Randomizer (Version 4.0). 2013. http://www.randomizer.org/ accessed 26 Jun 2018.

- 29.Doig GS, Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care. 2005;20(2):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005. discussion 91-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbakel JY, Aertgeerts B, Lemiengre M, et al. Analytical accuracy and user-friendliness of the Afinion point-of-care CRP test. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(1):83–86. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2013-201654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivanovska V, Hek K, Mantel Teeuwisse AK, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for children in primary care and adherence to treatment guidelines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(6):1707–1714. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cals JW, Butler CC, Hopstaken RM, et al. Effect of point of care testing for C reactive protein and training in communication skills on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b1374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gjelstad S, Høye S, Straand J, et al. Improving antibiotic prescribing in acute respiratory tract infections: cluster randomised trial from Norwegian general practice (prescription peer academic detailing (Rx-PAD) study) BMJ. 2013;347:f4403. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler CC, Simpson SA, Dunstan F, et al. Effectiveness of multifaceted educational programme to reduce antibiotic dispensing in primary care: practice based randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:d8173. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schot MJ, Broekhuizen BD, Cals JW. [Rules and regulations threaten non-pharmacological studies in children] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2015;160:A9354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kool M, Elshout G, Koes BW, et al. C-reactive protein level as diagnostic marker in young febrile children presenting in a general practice out-of-hours service. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):460–468. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.04.150315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rebnord IK, Sandvik H, Mjelle AB, et al. Factors predicting antibiotic prescription and referral to hospital for children with respiratory symptoms: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled study at out-of-hours services in primary care. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e012992. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MWvd L, Suijlekom-Smit LWAvan, Schellevis FG, et al. Tweede Nationale Studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk: het kind in de huisartspraktijk. (Second National Survey of morbidity and interventions in general practice: the child in general practice) NIVEL: Utrecht; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, van der Wouden JC, et al. Determinants of antibiotic overprescribing in respiratory tract infections in general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(5):930–936. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]