Abstract

AIM

To determine appropriate fecal calprotectin cut-off values for the prediction of endoscopic and histologic remission in Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).

METHODS

We performed a cross-sectional observational study of 131 Japanese patients with UC and measured fecal calprotectin levels by fluorescence enzyme immunoassay. The clinical activity of UC was assessed with the partial Mayo score (PMS). Relapse was defined as increase of PMS by 2 points or more in stool frequency or rectal bleeding subscore. The endoscopic and histologic activities of UC were evaluated in 50 patients within a 2-mo period from fecal sampling. Endoscopic activity was determined by Mayo endoscopic subscore, Rachmilewitz endoscopic index, and ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity. The histologic grade of inflammation was evaluated with biopsy specimens obtained from the endoscopically most severely inflamed site, according to the scheme by Matts grade and Riley’s score.

RESULTS

Fecal calprotectin levels varied from 1-20783 μg/g. There was a significant correlation between the partial Mayo score and fecal calprotectin levels (r = 0.548, P < 0.001). In 50 patients who underwent colonoscopy with biopsy, levels were significantly correlated with the Mayo endoscopic subscore (r = 0.574, P < 0.001), Rachmilewitz endoscopic index (r = 0.628, P < 0.001), ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (r = 0.613, P < 0.001), Riley’s histologic score (r = 0.400, P = 0.006), and Matts grade (r = 0.586, P < 0.001). Receiver-operating characteristic analyses identified the best cut-off value for the prediction of endoscopic remission as 288 μg/g, with an area under the curve of 0.777 or 0.823, while that for histologic remission was 123 or 125 μg/g, with an AUC of 0.881 or 0918, respectively. Of the 131 study patients, 88 patients in clinical remission were followed up 6 mo. During the follow-up period, 19 patients relapsed. The best fecal calprotectin cut-off value for predicting relapse was 175 μg/g.

CONCLUSION

Fecal calprotectin is a predictive biomarker for endoscopic and histologic remission in Japanese patients with UC.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Remission, Mucosal healing, Colonoscopy, Histology, Biomarker, Feces, Calprotectin

Core tip: In recent years, fecal calprotectin (FC) has been reported as a reliable surrogate marker for clinical, endoscopic and histologic activity in ulcerative colitis (UC). The aim of the present study was to determine appropriate FC cut-off values measured by fluorescence enzyme immunoassay (FEI) for predicting endoscopic and histologic remission in Japanese patients with UC. The best FC cut-off values predictive of histologic remission were 125 μg/g for Riley histologic score and 123 μg/g for Matts histologic grade. FC measured by FEI is a useful biomarker for predicting histologic remission in UC.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory disorder of the large intestine characterized by recurrent periods of clinical remission and disease relapse. In recent years, mucosal healing (MH) has been considered as an important therapeutic goal in inflammatory bowel diseases[1-7]. Achieving MH is associated with lower relapse rates, hospitalization rates, and surgery requirements. MH is often defined as a combination of clinical remission and endoscopic remission. However, histologic recovery is incomplete, even in patients with UC who achieve clinical and endoscopic remission[8-11]. Several reports have suggested that persistent active microscopic inflammation is associated with an increased risk of relapse[10-12]. In addition, the severity of such histologic inflammation is an important risk factor for colorectal neoplasia[4,13,14]. Hence, histologic remission should be an important goal in the management of UC.

Calprotectin is a calcium and zinc-binding protein produced mainly by neutrophils. It has been reported that fecal calprotectin (FC) levels reflect local inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. The FC level has been reported as a reliable surrogate marker of endoscopic and histologic activity in UC[15-19]. However, appropriate FC cut-off values for the prediction of endoscopic and histologic remission remain to be established in Japanese patients with UC.

The aim of the present study was to determine appropriate FC cut-off values for predicting endoscopic and histologic remission in Japanese patients with UC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This was a cross-sectional observational study of 131 Japanese patients with UC for measurement of FC during the period from December 2015 to July 2017. All patients were recruited at the Division of Gastroenterology, Iwate Medical University Hospital, Morioka, Japan. The diagnosis of UC was based on established clinical, endoscopic, radiological, and histological criteria. Type of UC was classified into total colitis, left-sided colitis, proctitis and segmental colitis. Segmental colitis was regarded as a disease with typical mucosal lesion without rectal involvement[20]. Blood samples were collected for the measurement of white blood cell (WBC) counts, hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), serum albumin levels, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels within a week from FC measurement.

The clinical activity of UC was assessed with the partial Mayo score (PMS)[21]; clinical remission was defined as a PMS of 0 without rectal bleeding and no requirement for steroid therapy in the previous 3 mo. Exclusion criteria were presence of infectious enterocolitis, colorectal cancer, Crohn’s disease, or indeterminate colitis; inability to collect fecal samples; pregnancy, history of colorectal resection, or regular intake of aspirin/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), defined as ≥ 2 tablets/week.

Definition of relapse

Of the 131 study patients with UC, 88 were in clinical remission (PMS = 0), and they were followed for a 6-mo period. Relapse was defined as increased stool frequency or rectal bleeding by a PMS increase of more than 2 points. Three patients who self-discontinued their medication were excluded.

FC assay

Stool samples were obtained on the morning of the scheduled day by patients themselves and stored at -20 °C until assay. FC was measured in a blind manner regarding the clinical and endoscopic profile, with a fluorescence enzyme immunoassay (FEI) (Phadia EliA™ Calprotectin 2).

Endoscopic and histological assessment

The endoscopic and histologic activity of UC were evaluated in 50 patients within a 2-mo period from fecal sampling. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, the indication for colonoscopy was heterogeneous among the study population. However, at least a single biopsy specimen was routinely obtained from the area of the most severe inflammation in subjects with active disease and from the rectum in subjects in remission.

Endoscopic activity was determined by Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES), Rachmilewitz endoscopic index (REI), and ulcerative colitis endoscopy index of severity (UCEIS)[21-23]. Endoscopic remission was defined as MES = 0, REI = 0, and UCEIS = 0. The histologic grade of inflammation was determined in biopsy specimens obtained from the endoscopically most severely inflamed site according to the scheme reported by Matts grade and Riley (Riley’s score)[24,25]. For Riley’s score, biopsy specimens were evaluated on a 5-point scale to measure the degree of chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate and tissue destruction[25]. The histologic grade was determined by a pathologist (TS), who was completely blinded to the endoscopic findings and FC levels. Histologic remission was defined as Matts grade = 1 and Riley’s score = 0. Four cases in which histological evaluation was difficult or biopsy samples were taken from inappropriate sites were excluded.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Iwate Medical University Hospital (H29-172), and the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (6th revision, 2008).

Statistical analysis

All of the statistical analyses were performed with the JMP® 13 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) and SPSS version 22 software for MAC OS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Numerical variables are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables are presented as frequencies. Associations between FC levels and blood tests, clinical disease activity, endoscopic activity or histologic activity were evaluated with the Spearman’s rank sum test. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn to estimate the area under the curve (AUC) and the best cut-off levels for FC to predict relapse and clinical, endoscopic, and histological remission. According to the cut-off levels, test significance, including sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, and accuracy were calculated. Associations between FC and other markers were examined by logistic regression analyses. Clinical characteristics were compared between relapsed patients and non-relapsed patients. Age and laboratory data were compared with the Wilcoxon test. Frequency by gender and medication were compared with the chi-square test. The types of disease extent were compared with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Relapse rate was compared between any two groups using Cox proportional hazard model. In each analysis, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline demographic characteristics of the study patients

The baseline demographic characteristics of the 131 patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. The median age was 41 (IQR 28-52) years, and 67 (51.1%) patients were male. The median duration of UC was 3.6 (IQR 2-10.1) years. Regarding disease extent, total colitis was seen in 76 (58.0%) patients, left-sided colitis in 24 (18.3%), proctitis in 29 (22.2%), and segmental colitis in 2 (1.5%). Among all 131 patients, FC levels varied from 1 to 20783 μg/g. The median FC level was 289 (IQR 78-785) μg/g. In most patients, medical treatment was administered; 112 patients were receiving oral mesalazine, 47 were receiving immunomodulators, 21 were receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor-α, and 17 were receiving a corticosteroid.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 131 study patients n (%)

| Parameter | n |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 41 (28-52) |

| Man/female | 67/64 |

| Disease duration, yr, median (IQR) | 3.6 (2.0-10.1) |

| Actual disease extent | |

| Proctitis | 29 (22.2) |

| Left-sided colitis | 24 (18.3) |

| Total colitis | 76 (58.0) |

| Segmental colitis | 2 (1.5) |

| Partial Mayo score | |

| < 2 | 93 (71.0) |

| 2-4 | 28 (21.4) |

| 5-7 | 8 (6.1) |

| > 7 | 2 (1.5) |

| Laboratory data | |

| WBC, /μL, median (IQR) | 6525 (4838-8140) |

| CRP, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.1 (0.04-0.20) |

| ESR, mm/h, median (IQR) | 7 (4-11) |

| Albumin, g/dL, median (IQR) | 4.3 (4.0-4.6) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, median (IQR) | 13.6 (12.1-14.3) |

| Platelets, × 1000/μL, median (IQR) | 268 (190-320) |

| FC, μg/g, median (IQR) | 289 (78-785) |

| Medication | |

| Mesalazine, oral | 112 (85.5) |

| Mesalazine, topical | 12 (9.2) |

| Immunomodulators | 47 (35.9) |

| Anti-TNF | 21 (16.0) |

| Corticosteroids | 17 (13.0) |

CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FC: Fecal calprotectin; IQR: Interquartile range; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; WBC: White blood cell.

Association between fecal calprotectin levels and blood test results

The level of FC was correlated with the levels of CRP (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient r = 0.467, P < 0.001), ESR (r = 0.355, P = 0.0003), serum albumin (r = -0.447, P < 0.001), hemoglobin (r = -0.353, P = 0.0002), and platelets (r = 0.300, P = 0.0018), but not with WBC counts (r = 0.157, P = 0.104).

Association between fecal calprotectin levels and clinical, endoscopic, or histologic activity

When the clinical disease activity in all 131 patients was compared based on the PMS and FC level, a positive correlation was found between the FC level and the grade of clinical activity (r = 0.548, P < 0.001). The best FC cut-off value was calculated to be 289 μg/g (AUC: 0.796; 95%CI: 0.714-0.878) for predicting clinical remission determined by PMS with a sensitivity of 72% and a specificity of 84%.

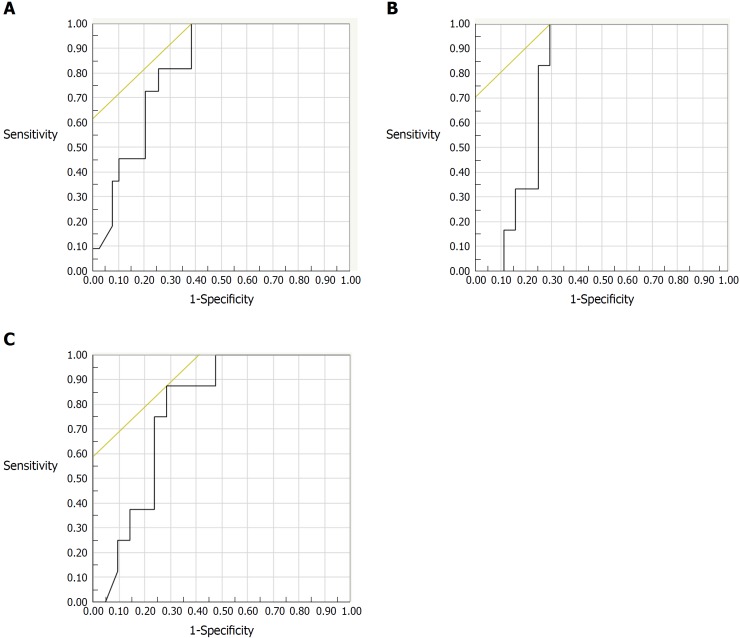

The correlation between endoscopic activity and FC could be examined in 50 subjects. The indication for colonoscopy was clinically active disease or exacerbation of clinical symptoms in 14 subjects, assessment of therapeutic efficacy in 12 subjects, and surveillance for colorectal cancer in 24 subjects. Among those subjects, FC levels increased along with increasing severity of endoscopic activity evaluated by MES (r = 0.574, P < 0.001), REI (r = 0.628, P < 0.001), and UCEIS (r = 0.613, P < 0.001). For predicting endoscopic remission, the best FC cut-off value was 490 μg/g for the MES (AUC: 0.823; 95%CI: 0.707-0.939) with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 62% (Figure 1A), while it was 288 μg/g for both the REI (AUC: 0.780; 95%CI: 0.658-0.903) and the UCEIS (AUC: 0.777; 95%CI: 0.645-0.909) (Figure 1B and C). A logistic regression analysis including FC, CRP, WBC, ESR and platelet count as co-variables revealed that there was not a statistically significant correlation between FC and endoscopic remission defined as UCEIS = 0.

Figure 1.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves for fecal calprotectin levels to predict endoscopic remission of ulcerative colitis (n = 50). A: ROC for FC levels in predicting remission by Mayo endoscopic subscore. The AUC was 0.823, 95%CI: 0.707-0.939. The best cut-off value of FC was 490 μg/g, with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 62%; B: ROC for FC in predicting remission by the Rachmilewitz endoscopic index. The AUC was 0.780, 95%CI: 0.658-0.903. The best cut-off value of FC was 288 μg/g, with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 70%; C: ROC for FC level in predicting remission by the ulcerative colitis endoscopy index of severity. The AUC was 0.777, 95%CI: 0.645-0.909. The best cut-off value of FC was 288 μg/g, with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 71%. ROC: Receiver-operating characteristic; FC: Fecal calprotectin; AUC: Area under the curve.

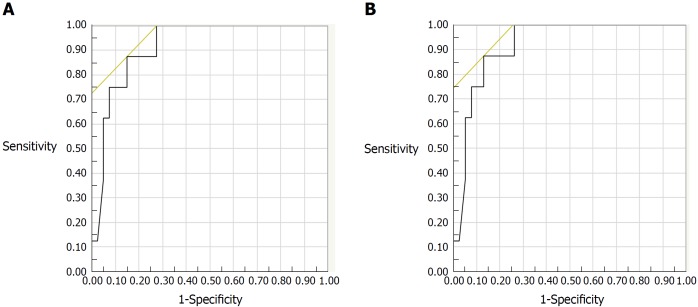

Biopsy specimens were obtained from 46 patients during colonoscopy. Among 46 subjects evaluated histologically, FC levels increased with increasing histologic inflammatory activity by both Matts grade (r = 0.586, P < 0.001), and Riley’s score (r = 0.400, P = 0.006). For predicting histologic remission, the best FC cut-off values were 125 μg/g for the Riley score (AUC: 0.881; 95%CI: 0.780-0.981) and 123 μg/g for the Matts grade (AUC: 0.918; 95%CI: 0.831-1.000) (Figure 2A and B). A logistic regression analysis revealed that FC was a single and independent factor associated with histologic remission defined as Matts grade = 1 (P = 0.005).

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves for fecal calprotectin levels in predicting the histologic remission of ulcerative colitis (n = 46). A: ROC for FC in predicting remission by Riley’s score. The AUC was 0.881, 95CI: 0.780-0.981. The best cut-off value of FC was 125 μg/g, with a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 86%; B: ROC for FC in predicting remission by Matts grade. The AUC was 0.918, 95%CI: 0.831-1.000. The best cut-off value of FC was 123 μg/g, with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 87%. ROC: Receiver-operating characteristic; FC: Fecal calprotectin; AUC: Area under the curve.

Association between fecal calprotectin levels and relapse

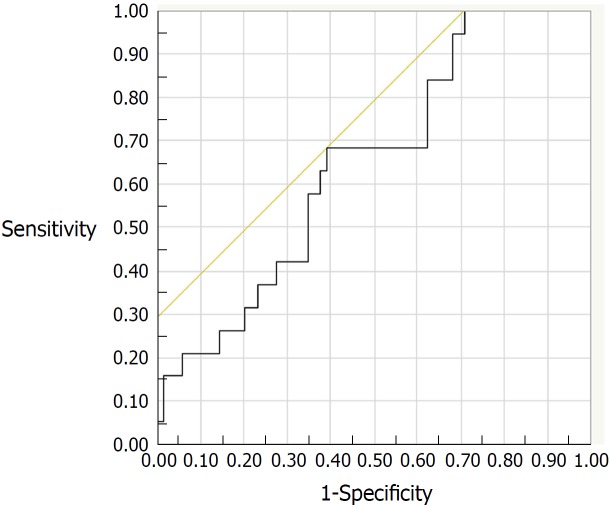

Of the 131 study patients, 88 patients in clinical remission (PMS = 0) were followed up. During the 6-mo period after FC measurement, 19 (21.6%) of the 88 patients experienced a relapse of UC. Clinical characteristics of the relapsed and non-relapsed patients are compared in Table 2. Medication with oral mesalazine was more frequent in non-relapsed patients than in relapsed patients (P = 0.03). The ROC analysis estimated a FC cut-off value of 175 μg/g (AUC: 0.648; 95%CI: 0.517-0.778) for predicting relapse, with a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 61% (Figure 3). However, Cox proportional hazard model revealed that neither FC nor other co-variables was an independent predictive factor for clinical relapse within 6-mo period.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of relapsed and non-relapsed patients n (%)

| Parameter | Relapsed patients (n = 19) | Non-relapsed patients (n = 69) | P value |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 35 (23-53) | 40 (29-52) | 0.26 |

| Male/female | 6/13 | 37/32 | 0.08 |

| Actual disease extent | |||

| Proctitis | 5 (26.3) | 18 (26.1) | 0.53 |

| Left-sided colitis | 1 (5.3) | 12 (17.4) | |

| Total colitis | 13 (68.4) | 38 (55.1) | |

| Segmental colitis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Laboratory data | |||

| WBC, /μL, median (IQR) | 6130 (5110-7745) | 5585 (4640-7013) | 0.48 |

| CRP, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.05 (0.01-0.10) | 0.1 (0.04-0.14) | 0.05 |

| ESR, mm/h, median (IQR) | 6 (4-8) | 5 (3.0-10.0) | 0.69 |

| Albumin, g/dL, median (IQR) | 4.4 (4.3-4.6) | 4.4 (4.1-4.6) | 0.75 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, median (IQR) | 13.3 (12.3-14.4) | 13.9 (12.6-14.9) | 0.25 |

| Platelets, × 1000/μL, median (IQR) | 238 (214-339) | 256 (213-294) | 0.92 |

| FC, μg/g, median (IQR) | 303 (94-846) | 126 (55.5-485) | 0.05 |

| Medication | |||

| Mesalazine, oral | 14 (73.7) | 64 (92.8) | 0.03 |

| Mesalazine, topical | 1 (5.3) | 3 (4.3) | 0.87 |

| Immunomodulators | 6 (31.6) | 18 (26.1) | 0.98 |

| Anti-TNF | 4 (21.1) | 12 (17.4) | 0.71 |

| Corticosteroids | 3 (15.8) | 5 (7.2) | 0.28 |

CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FC: Fecal calprotectin; IQR: Interquartile range; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; WBC: White blood cell.

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristic curve for fecal calprotectin levels to predict relapse at the six-month follow-up assessment (AUC: 0.648; 95%CI: 0.517-0.778). The best cut-off value was 175 μg/g, with a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 61%. AUC: Area under the curve.

Table 3 summarizes the performance of FC levels using the appropriate cut-off values in our cohort of patients with UC.

Table 3.

Test characteristics of fecal calprotectin levels to predict relapse and remission

| Variable | Cut-off value (μg/g) | AUC | 95%CI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity(%) | PPV (%) | PLR | Accuracy (%) |

| Relapse | 175 | 0.648 | 0.517-0.778 | 68 | 61 | 33 | 1.75 | 63 |

| PMS 0 | 289 | 0.796 | 0.714-0.878 | 72 | 84 | 88 | 4.48 | 76 |

| MES 0 | 490 | 0.823 | 0.707-0.939 | 100 | 62 | 42 | 2.6 | 70 |

| REI 0 | 288 | 0.78 | 0.658-0.903 | 100 | 70 | 32 | 3.38 | 74 |

| UCEIS 0 | 288 | 0.777 | 0.645-0.909 | 88 | 71 | 37 | 3.06 | 74 |

| Riley’s score 0 | 125 | 0.881 | 0.780-0.981 | 80 | 86 | 62 | 5.76 | 85 |

| Matts grade 1 | 123 | 0.918 | 0.831-1.000 | 88 | 87 | 58 | 6.65 | 87 |

AUC: Area under the curve; CI: Confidence interval; PPV: Positive-predictive value; PLR: Positive likelihood ratio; PMS: Partial Mayo score; MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; REI: Rachmilewitz endoscopic index; UCEIS: Ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the association between FC levels and laboratory data and clinical, endoscopic, and histologic disease activity and risk of relapse. The results showed that FC was closely related to the laboratory data (CRP, ESR, serum albumin, hemoglobin, platelets) and to the clinical, endoscopic and histologic disease activity. While FC has been measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) in previous investigations[15,17-19], we measured FC levels with a FEI in the present study. Even though FC measured by FEI has been shown to be an appropriate marker for patients with UC[16,26,27], it has also been confirmed that measurement by FEI results in a wide range of the test value when compared to measurement by ELISA[27]. We thus presume that high cut-off values of FC as found in our study may be a consequence of FEI measurement.

Based on the interpretations of the ROCs, we obtained FC cut-off levels of 289 μg/g for predicting clinical remission, and 288 or 490 μg/g to predict endoscopic remission. The FC cut-off value for MES (490 μg/g) was higher than that for REI and UCEIS (288 μg/g). This is probably because the numbers of evaluated items are greater with the REI and UCEIS than with the MES. We obtained the FC cut-off levels of 123 μg/g and 125 μg/g to predict histologic remission, as determined by the Matts grade and Riley score, respectively. Both of the determined FC values were close to each other, and the evaluation ability is considered nearly equivalent.

The therapeutic goal for patients with UC has recently shifted from symptom control to the combination of endoscopic and histologic remission with MH, because this has been found to be a better predictor of long-term remission and prevention of the need for hospitalizations and surgeries[1-7]. Previous studies showed that patients with a MES value of 1 are more likely to relapse and they are prone to colectomy than those with a MES of 0[28,29]. Further, achieving histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalization[30]. Several previous studies reported that microscopic inflammation persists in some patients with endoscopic MH[31,32]. In the present study, we found that about 50% of patients had residual inflammation in the mucosa (Matts grade ≥ 2) despite having been judged to be in endoscopic remission (UCEIS = 0). Accordingly, histological remission seems more important as a rational therapeutic target[33]. Previous studies reported the cut-off levels FC to range from 60-200 μg/g for histological remission[15,17,34-38]. We found that a lower FC cut-off value predicted histological remission rather than clinical and endoscopic remission. Furthermore, logistic regression analyses revealed that FC was an independent factor associated with histological remission. While recent treat-to-target concept for UC itemized that either histology or FC is not a target for the treatment of UC, they are regarded as being adjunctive for the management of UC[39]. Our observation suggests that a simple measurement of FC is a substantial alternative for the evaluation of histologic severity of UC.

In our study, the FC cut-off value for prediction of relapse in UC was determined to be 175 μg/g. However, sensitivity and specificity for the prediction of relapse were less than 70%, and AUC for the prediction was less than 0.7. In addition, a multivariate analysis failed to identify FC as a predictive factor for clinical relapse. This observation does not conform to previous reports showing the accuracy of FC for the prediction of relapse in UC[19,34,35,40]. In our study population, however, the overall rate of relapse was high with a value of 14%. In addition, colonoscopy was not performed at the time when PMS was found to be zero. Therefore, it seems possible that we recruited subjects without mucosal healing, thus being prone to relapse, for the analysis.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, our cross-sectional study design makes it possible to observe associations at a specific time point, but gives no information about longitudinal clinical end points, such as the prognostic value of FC. Second, we assessed endoscopic and histological activity by sigmoidoscopy or total colonoscopy. However, the original endoscopic items of the Mayo scoring system were evaluated by sigmoidoscopy[21]. In the case of sigmoidoscopy, the FC levels may have been affected by the degree of proximal colonic inflammation. Third, the clinical disease condition of the patients at the time of stool sampling varied. Finally, the study was performed at a single center and involved a limited number of patients.

In conclusion, our analysis indicates that FC measured by FEI is a useful biomarker in Japanese patients with UC. It is considered appropriate for the prediction of mucosal lesions and histologic activity rather than clinical activity of UC. However, the appropriateness of FC measured by FEI for the prediction of relapse of UC awaits further elucidation.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Fecal calprotectin (FC) is a useful biomarker to assess disease activity in ulcerative colitis (UC). However, appropriate cut-off values of FC for the endoscopic and histologic remission has not yet been determined in Japanese patients with UC.

Research motivation

Calculating the FC cut-off value of the remissions will help to evaluate disease activity instead of invasive examination such as endoscopy.

Research objectives

To determine cut-off values of FC for endoscopic and histologic remission in Japanese patients with UC.

Research methods

We performed a retrospective study of Japanese patients with UC for measurement of FC that was measured by fluorescence enzyme immunoassay (FEI). We analyzed the relationship between FC and laboratory data, clinical activity, endoscopic score (Mayo endoscopic subscore: MES, Rachmilwitz endoscopic index: REI, ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity: UCEIS and histologic score (Matts grade, Riley’s histologic score).

Research results

In 131 patients, there was a statistically significant correlation between PMS and FC (P < 0.001). FC levels were significantly correlated with the MES (P < 0.001), REI (P < 0.001), UCEIS (P < 0.001), Riley’s histologic score (P = 0.006), and Matts grade (P < 0.001). Receiver-operating characteristic analyses identified the best cut-off value for the prediction of endoscopic remission as 288 μg/g, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.777 or 0.823, while that for histologic remission was 123 or 125 μg/g or 125 μg/g, with an AUC of 0.881 or 0.918.

Research conclusions

FC measured by FEI is considered a predictive biomarker for endoscopic and histologic remission in Japanese patients with UC.

Research perspectives

Our study showed that FC was useful biomarker for prediction of endoscopic and histologic activity. This research was a retrospective study, which is the maximum limitation. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm the reproducibility of the results of this research.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iwate Medical University Hospital.

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent as this is a retrospective study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no conflicts-of-interest related to this article.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: July 10, 2018

First decision: August 27, 2018

Article in press: October 5, 2018

P- Reviewer: Eleftheriadis NP, Lankarani KB, Seicean A S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

Contributor Information

Jun Urushikubo, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan. urujun50@gmail.com.

Shunichi Yanai, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Shotaro Nakamura, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Keisuke Kawasaki, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Risaburo Akasaka, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Kunihiko Sato, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Yosuke Toya, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Kensuke Asakura, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Takahiro Gonai, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Tamotsu Sugai, Division of Molecular Diagnostic Pathology, Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

Takayuki Matsumoto, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Iwate Medical University, Morioka 020-8505, Japan.

References

- 1.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH; IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardizzone S, Cassinotti A, Duca P, Mazzali C, Penati C, Manes G, Marmo R, Massari A, Molteni P, Maconi G, et al. Mucosal healing predicts late outcomes after the first course of corticosteroids for newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:483–489.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, Esser D, Wang Y, Lang Y, Marano CW, Strauss R, Oddens BJ, Feagan BG, et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1194–1201. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meucci G, Fasoli R, Saibeni S, Valpiani D, Gullotta R, Colombo E, D’Incà R, Terpin M, Lombardi G; IG-IBD. Prognostic significance of endoscopic remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis treated with oral and topical mesalazine: a prospective, multicenter study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1006–1010. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619–1635. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papi C, Fascì-Spurio F, Rogai F, Settesoldi A, Margagnoni G, Annese V. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: treatment efficacy and predictive factors. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:978–985. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baars JE, Nuij VJ, Oldenburg B, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Majority of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission have mucosal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1634–1640. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg L, Nanda KS, Zenlea T, Gifford A, Lawlor GO, Falchuk KR, Wolf JL, Cheifetz AS, Goldsmith JD, Moss AC. Histologic markers of inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Dutt S, Herd ME. Microscopic activity in ulcerative colitis: what does it mean? Gut. 1991;32:174–178. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bitton A, Peppercorn MA, Antonioli DA, Niles JL, Shah S, Bousvaros A, Ransil B, Wild G, Cohen A, Edwardes MD, et al. Clinical, biological, and histologic parameters as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:13–20. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bessissow T, Lemmens B, Ferrante M, Bisschops R, Van Steen K, Geboes K, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, De Hertogh G. Prognostic value of serologic and histologic markers on clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1684–1692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutter M, Saunders B, Wilkinson K, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm M, Williams C, Price A, Talbot I, Forbes A. Severity of inflammation is a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:451–459. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, Hossain S, Matula S, Kornbluth A, Bodian C, Ullman T. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099–1105; quiz 1340-1341. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guardiola J, Lobatón T, Rodríguez-Alonso L, Ruiz-Cerulla A, Arajol C, Loayza C, Sanjuan X, Sánchez E, Rodríguez-Moranta F. Fecal level of calprotectin identifies histologic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical and endoscopic remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi S, Takeuchi Y, Arai K, Fukuda K, Kuroki Y, Asonuma K, Takahashi H, Saruta M, Yoshida H. Fecal calprotectin is a clinically relevant biomarker of mucosal healing in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:93–98. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theede K, Holck S, Ibsen P, Ladelund S, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Nielsen AM. Level of Fecal Calprotectin Correlates With Endoscopic and Histologic Inflammation and Identifies Patients With Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1929–1936.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taghvaei T, Maleki I, Nagshvar F, Fakheri H, Hosseini V, Valizadeh SM, Neishaboori H. Fecal calprotectin and ulcerative colitis endoscopic activity index as indicators of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s11739-014-1144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theede K, Holck S, Ibsen P, Kallemose T, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Nielsen AM. Fecal Calprotectin Predicts Relapse and Histological Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1042–1048. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SH, Yang SK, Park SK, Kim JW, Yang DH, Jung KW, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, et al. Atypical distribution of inflammation in newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis is not rare. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:125–130. doi: 10.1155/2014/834512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. BMJ. 1989;298:82–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6666.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lémann M, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Developing an instrument to assess the endoscopic severity of ulcerative colitis: the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) Gut. 2012;61:535–542. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MATTS SG. The value of rectal biopsy in the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. Q J Med. 1961;30:393–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Herd ME, Dutt S, Turnberg LA. Comparison of delayed release 5 aminosalicylic acid (mesalazine) and sulphasalazine in the treatment of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis relapse. Gut. 1988;29:669–674. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.5.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kittanakom S, Shajib MS, Garvie K, Turner J, Brooks D, Odeh S, Issenman R, Chetty VT, Macri J, Khan WI. Comparison of Fecal Calprotectin Methods for Predicting Relapse of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:1450970. doi: 10.1155/2017/1450970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labaere D, Smismans A, Van Olmen A, Christiaens P, D’Haens G, Moons V, Cuyle PJ, Frans J, Bossuyt P. Comparison of six different calprotectin assays for the assessment of inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:30–37. doi: 10.1177/2050640613518201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manginot C, Baumann C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. An endoscopic Mayo score of 0 is associated with a lower risk of colectomy than a score of 1 in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2015;64:1181–1182. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barreiro-de Acosta M, Vallejo N, de la Iglesia D, Uribarri L, Bastón I, Ferreiro-Iglesias R, Lorenzo A, Domínguez-Muñoz JE. Evaluation of the Risk of Relapse in Ulcerative Colitis According to the Degree of Mucosal Healing (Mayo 0 vs 1): A Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:13–19. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, Walsh AJ, Thomas S, von Herbay A, Buchel OC, White L, Brain O, Keshav S, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut. 2016;65:408–414. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, Koehler HH, Stolte M, Kanzler S, Nafe B, Jung M, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:880–888. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tontini GE, Vecchi M, Neurath MF, Neumann H. Review article: newer optical and digital chromoendoscopy techniques vs. dye-based chromoendoscopy for diagnosis and surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1198–1208. doi: 10.1111/apt.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryant RV, Winer S, Travis SP, Riddell RH. Systematic review: histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is ‘complete’ remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1582–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.García-Sánchez V, Iglesias-Flores E, González R, Gisbert JP, Gallardo-Valverde JM, González-Galilea A, Naranjo-Rodríguez A, de Dios-Vega JF, Muntané J, Gómez-Camacho F. Does fecal calprotectin predict relapse in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis? J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gisbert JP, Bermejo F, Pérez-Calle JL, Taxonera C, Vera I, McNicholl AG, Algaba A, López P, López-Palacios N, Calvo M, et al. Fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin for the prediction of inflammatory bowel disease relapse. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1190–1198. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zittan E, Kelly OB, Kirsch R, Milgrom R, Burns J, Nguyen GC, Croitoru K, Van Assche G, Silverberg MS, Steinhart AH. Low Fecal Calprotectin Correlates with Histological Remission and Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis and Colonic Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:623–630. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel A, Panchal H, Dubinsky MC. Fecal Calprotectin Levels Predict Histological Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1600–1604. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mak WY, Buisson A, Andersen MJ Jr, Lei D, Pekow J, Cohen RD, Kahn SA, Pereira B, Rubin DT. Fecal Calprotectin in Assessing Endoscopic and Histological Remission in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1294–1301. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-4980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, D’Haens G, Dotan I, Dubinsky M, Feagan B, et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324–1338. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jauregui-Amezaga A, López-Cerón M, Aceituno M, Jimeno M, Rodríguez de Miguel C, Pinó-Donnay S, Zabalza M, Sans M, Ricart E, Ordás I, et al. Accuracy of advanced endoscopy and fecal calprotectin for prediction of relapse in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1187–1193. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]