Abstract

Worldwide, more than one million people die each year from hepatitis C virus (HCV) related diseases, and over 300 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis B or C. Egypt used to be on the top of the countries with heavy HCV burden. Some countries are making advances in elimination of HCV, yet multiple factors preventing progress; remain for the majority. These factors include lack of global funding sources for treatment, late diagnosis, poor data, and inadequate screening. Treatment of HCV in Egypt has become one of the top national priorities since 2007. Egypt started a national treatment program intending to provide cure for Egyptian HCV-infected patients. Mass HCV treatment program had started using Pegylated interferon and ribavirin between 2007 and 2014. Yet, with the development of highly-effective direct acting antivirals (DAAs) for HCV, elimination of viral hepatitis has become a real possibility. The Egyptian National Committee for the Control of Viral Hepatitis did its best to provide Egyptian HCV patients with DAAs. Egypt adopted a strategy that represents a model of care that could help other countries with high HCV prevalence rate in their battle against HCV. This review covers the effects of HCV management in Egyptian real life settings and the outcome of different treatment protocols. Also, it deals with the current and future strategies for HCV prevention and screening as well as the challenges facing HCV elimination and the prospect of future eradication of HCV.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Egypt, Direct acting antivirals, Screening, Elimination, Limitations

Core tip: Egypt started a large treatment program intended to provide therapy for Egyptian hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients. The Egyptian National Committee for the Control of Viral Hepatitis provides a model of care that could help other countries with high HCV prevalence rate in their battle against HCV. This review covers the results of HCV management in Egyptian real life settings and the outcome of different treatment protocols. Also, it covers the current and future strategies for HCV prevention and screening. Lastly, we discussed the challenges facing HCV elimination and the prospect of future eradication of HCV.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major health problem worldwide. In 2015, the global prevalence of HCV infection was 1.0%, with the highest prevalence in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (2.3%) followed by the European one (1.5%). The annual mortality due to HCV-related complications is estimated to be approximately 700000 deaths[1].

Seven HCV genotype strains have been identified and classified according to the phylogenetic and sequence analyses of the whole viral genomes[2]. Genotype strains differ at 30%-35% of the nucleotide sites[3]. HCV genotype 4 is the predominant type among chronically infected Egyptian patients[4].

HCV BURDEN IN EGYPT

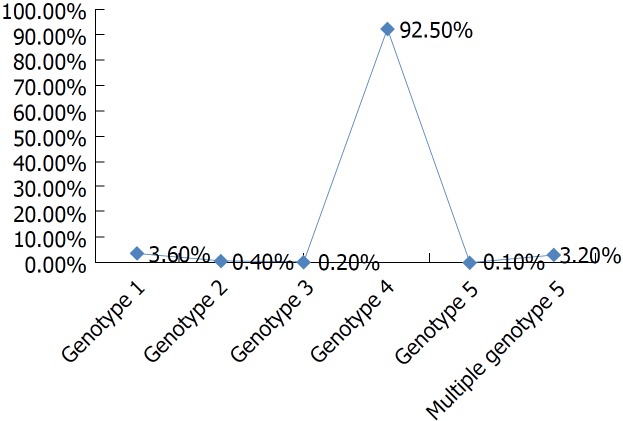

The highest prevalence of HCV infection is present in Egypt, with 92.5% of patients infected with genotype 4, 3.6% patients with genotype 1, 3.2% patients with multiple genotypes, and < 1% patients with other genotypes[2,3,5,6] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of different hepatitis C virus genotypes in Egypt.

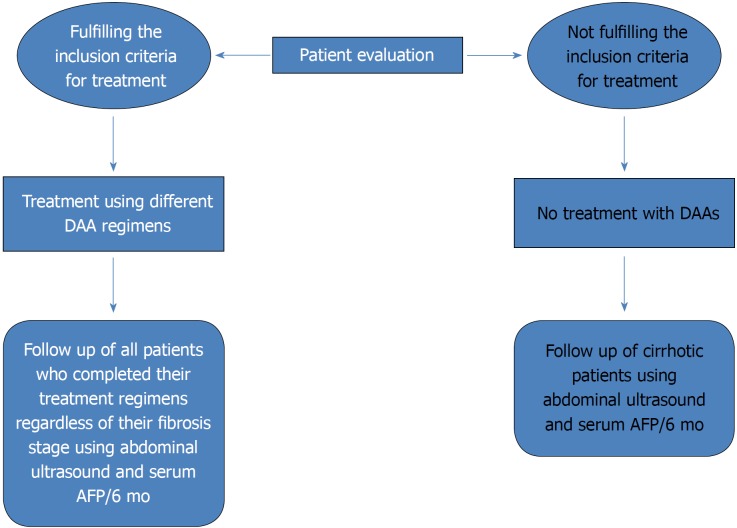

In Egypt, widespread HCV infection was caused by a mass-scale treatment campaign of intravenous antischistosomal injections executed between 1950 and 1980[7]. In 1996, the HCV seroprevalence was > 40% among adults, whereas in 2008, the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) showed a seroprevalence of 14.7% and viremic prevalence of 9.7% in 15-59-year-old patients[8,9]. The latest DHS in 2015 reported a seroprevalence of 10% and viremic prevalence of 7%[10]. As per the DHS, the HCV burden significantly decreased approximately 30% between 2008 and 2015 (Figure 2). However, in the 2008 DHS, this apparent decline in HCV seroprevalence was not attributed exclusively to the decrease in the newly acquired infections but to the aging of patients infected 50 years ago in the mass campaigns held for treatment of schistosomiasis[11].

Figure 2.

Timeline of hepatitis C virus prevalence in Egypt among adults.

Notably, HCV is mostly prevalent among lower socioeconomic sections of the population[12]. The HCV prevalence rate is higher in rural areas (12%) than in urban areas (7%); HCV prevalence is also related to wealth: 12% in the lowest wealth quintile compared to 7% in the highest quintile. In Egypt, 26% of the population lives below the national poverty line with income of < 1.6 USD per day[9]. Therefore, hepatitis C infection can be considered as a socioeconomic condition.

In addition to economic burden, HCV infection causes life-compromising health burden. It was estimated that the annual rates of liver decompensation, death/transplantation, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in HCV patients to be 6.37%, 4.58%, and 3.36%, respectively[13].

In 2015, the economic burden of HCV in Egypt was estimated to be $3.81 billion, whereas direct health care costs of HCV-associated diseases exceeded $700 million annually[14]. It is expected that the economic burden will exponentially increase as HCV-infected individuals progress to more advanced disease stages of decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, and liver-related mortality[15]. The cumulative total economic burden of HCV disease was estimated at $89.1 billion between 2013 and 2030[16].

NATIONAL TREAMENT PROGRANM FOR MANAGING HCV IN EGYPT

In response to the major problem of HCV in Egypt, the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population (MOH) launched the National Committee for Control of Viral Hepatitis (NCCVH) in 2006 to be in charge of combating HCV epidemic in the country[17]. The Egyptian NCCVH started its work by issuing the national treatment strategy for controlling HCV infection, which represented the road map for the activity of NCCVH[18]. Many stakeholders were represented in the NCCVH, including experts in the field of HCV from Egypt in addition to some international experts[19]. Based on the national treatment strategy, the main initiative tasks for the NCCVH were to estimate the actual HCV disease burden and develop a reliable infrastructure to function as a base for the national treatment program activities[17,20]. The main challenge at that time was the high cost of antiviral medications, and thus, providing such medications for free (on the expense of the MOH) or at a highly reduced cost was the main pillar for attracting patients to the project. The infrastructure of the program relied mainly on establishing a wide network of specialized centers that provide integrated care for HCV patients. This integrated care includes all required services needed for HCV management, including screening, evaluation of the patients for their eligibility for treatment, administration of therapy, and follow-up during as well as after treatment. A well-trained multidisciplinary team, composed of hepatologists, pathologists, radiologists, clinical pharmacists, and all other specialties participating in assessment and follow-up, in each center is in charge of the management of patients[17]. These centers reached 64 facilities in 2018, covering the country with < 50 km between every two bordering centers, and were interconnected through a special dedicated intranet.

The National Network for Treatment Centers responsible for data transfer and other administrative issues, monitoring work progress, issuing treatment protocols, and overseeing these centers comes under the governance of the NCCVH. After the introduction of new direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), the story continued with obtaining these drugs at very low prices through negotiations between the NCCVH and the manufacturing companies. This allowed the treatment of a large number of patients in the first phase of the treatment program, and the number maximized to approximately 150000 patients in 3 years after the introduction of the locally produced generic DAAs. As expected, such a large nationwide program represented a huge financial challenge to a resource-limited country like Egypt. The main funds for the program were through the governmental support funds issued to patients who are not under the umbrella of health insurance[20]. These funds were utilized for pre-treatment investigations, cost of medications, and follow-up laboratory tests during treatment.

RESULTS OF HCV MANAGEMENT IN EGYPTIAN REAL-LIFE SETTINGS

The mass HCV treatment program started administering pegylated interferon and ribavirin between 2007 and 2014[17]. However, the response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin was not satisfactory and was associated with many adverse events[21].

In October 2014, the introduction of sofosbuvir markedly changed therapeutic outcomes (Table 1). Ruane et al[22] treated 60 chronic hepatitis C patients of Egyptian ancestry with sofosbuvir and ribavirin for 12 wk or 24 wk. In their study, sustained virological response (SVR) rates ranged from 68% to 93%, being more in patients who received 24 wk of therapy. Similar results were obtained in Egypt by Doss et al [23] who used sofosbuvir and ribavirin for treating treatment-naive and experienced patients. SVR rates were 77% in patients treated for 12 wk and 90% in those treated for 24 wk, with favorable response in non-cirrhotic patients.

Table 1.

Highlight on some recent studies exploring the efficacy of different direct acting antivirals combinations in Egypt

| Ref. | Year of publication | Number of patients | Regimen used | Sustainted virologic response rate |

| Ruane et al[22] | 2015 | 60 | Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for 12 wk or 24 wk | 68% for 12 wk or 24 wk and 93% for patients treated for 24 wk |

| Doss et al[23] | 2015 | 103 | Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for 12 wk or 24 wk | 77% in patients treated for 12 wk and 90% for patients treated for 24 wk |

| Elsharkawy et al[24] | 2017 | 14409 | Triple; sofosbuvir, pegylated interferon and ribavirin versus dual; sofosbuvir and ribavirin | 94% with triple therapy and 78.7% with dual therapy |

| El Kassas et al[25] | 2018 | 7042 | Different combinations used | 82.9%-100.0% |

| Ahmed et al[26] | 2018 | 300 | Sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir with or without ribavirin for 12-24 wk | 96.55% and 84.54% |

| Abd-Elsalam et al[27] | 2018 | 2400 | Sofosbuvir and ribavirin | 71.20%. |

| El Kassas et al[28] | 2018 | 10083 | A 4-wk lead-in phase of sofosbuvir, pegylated interferon and ribavirin followed by 12 wk therapy with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir versus 12 wk therapy with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir | 100% in those whoe received the lead in phase treatment regimen and 98.9% in those who received sofosbuvir and daclatasvir only |

| El-Khayat et al[29] | 2017 | 583 | Sofosbuvir and simeprevir for 12 wk | 95.70% |

| Eletreby et al[30] | 2017 | 6211 | Sofosbuvir and simeprevir for 12 wk | 94.00% |

| Abdel-Moneim et al[31] | 2018 | 946 | Sofosbuvir, daclatasvir versus Sofosbuvir, daclatasvir and ribavirin | 95% and 92% |

| Omar et al[34] | 2018 | 18378 | Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir | 95.10%. |

| El-Khayat et al[35] | 2018 | 144 | Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir | 99.00% |

| Elsharkawy et al[36] | 2018 | 337042 | Different combinations used | 82.7% to 98.0% |

Elsharkawy et al[24] compared interferon-containing sofosbuvir triple therapy (sofosbuvir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin) versus dual therapy (sofosbuvir and ribavirin) in 14409 patients and found the SVR rates to be 94% with triple therapy and 78.7% with dual therapy. Predictors of SVR were female gender, being easy to treat patient, and previous treatment with interferon and ribavirin. El kassas et al[25] evaluated the efficacy of different DAA combinations in Egyptian patients receiving treatment in one of the NCCVH centers and found the SVR rates to be 82.9%-100%.

In the study by Ahmed et al[26], sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir with or without ribavirin for 12-24 wk were used to treat 300 HCV genotype 4 Egyptian patients and the SVR12 rates were 96.55% in non-cirrhotic and 84.54% in cirrhotic patients. Further, Abd-Elsalam et al[27] assessed the safety of dual therapy (sofosbuvir and ribavirin) in 2400 cirrhotic patents and found the overall SVR rate to be 71.2%.

In another interesting and unique study, El Kassas et al[28] evaluated a 4-wk lead-in phase of sofosbuvir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin, followed by a 12-wk therapy with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir. In their study, the SVR rates were surprisingly very high (100%) compared with that in a group of patients who received the 12-wk therapy with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir without lead-in phase treatment (SVR: 98.9%).

The combination of sofosbuvir plus simeprevir has been tested in two large real-life cohorts in Egypt[29,30]. In a study by El-Khayat et al[29], a 12-wk regimen of simeprevir plus sofosbuvir led to an overall SVR rate of 95.7%, which increased to 98.9% in patients with mild fibrosis and to 100% in treatment-experienced patients. Another study using simeprevir plus sofosbuvir achieved overall SVR rates of 94% and SVR rates of 96% and 93% in easy- and difficult-to-treat groups, respectively[30].

Sofosbuvir, daclatasvir, and ribavirin combination has proven to be safe and effective in several studies in Egypt. A cohort of 946 Egyptian patients with chronic HCV was enrolled for treatment with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir with and without ribavirin[31]. An overall SVR12 rate of 94% was achieved; 95% in the easy-to-treat group receiving Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir, and 92% in the difficult-to-treat group receiving Sofosbuvir, daclatasvir, and ribavirin[31]. El-Khayat et al[32] reported 92% SVR rates in naïve cirrhotic patients and 87% in previously treated patients. Most reported adverse events included anemia, fatigue, headache, and pruritus. Serious adverse events were HCC and hepatic encephalopathy, and they were present in patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh score class B. Mohemd et al[33] showed that DAA combinations led to improvements in biochemical parameters and clinical outcomes in their study.

A large cohort of patients (18378) who received generic sofosbuvir /daclatasvir with or without ribavirin showed an overall SVR rate of 95.1% and a discontinuation rate of 1.5%, with most discontinuations being due to patient withdrawal and pregnancy[34]. Mortality was reported in five patients[34].

Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir combination has recently been approved for treating adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. El-Khayat et al[35] evaluated the safety and efficacy of this regimen in Egyptian adolescents and found it to be well tolerated, safe, and effective, with SVR12 rates of 99%. Relapses were more in treatment-naïve patients, and no case of serious adverse events, treatment discontinuation, or death was reported. Skin rash, pruritus, and diarrhea were the minor adverse events observed[35].

In the study that evaluated real-life HCV treatment outcomes of DAAs in the largest cohort of 337042 patients with different fibrosis stages (F0-F4) in Egypt, sofosbuvir and ribavirin therapy for 24 wk showed the lowest SVR12 rate (82.7%) compared with other regimens that showed SVR rates between 94% and 98%[36].

Another recent study has evaluated adverse events in 149,816 chronic hepatitis C patients treated with different regimens in the national HCV treatment program in Egypt. In this study, adverse events developed in 1.7% patients, with serious adverse events occurring in 68% of them, mainly in patients treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Anemia and hyperbilirubinemia were the most commonly reported adverse events. HCC and mortality were reported in 0.02% and 0.06% of treated patients, respectively. Adverse events were more common in patients who were males and with cirrhosis, high bilirubin levels, and low hemoglobin, platelet, and albumin levels[37].

PREVENTIVE MEASURES AND AWARENESS CAMPAIGNS

Egypt is supporting a comprehensive approach for tackling hepatitis through “Plan of action for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis, Egypt 2014-2018”[38,39].

Primary prevention of HCV

Primary prevention of disease requires strict measures to prevent HCV transmission to vulnerable people. This aim can be achieved by

Strengthening surveillance to detect viral hepatitis transmission and disease: Guided by the MOH viral hepatitis centers, surveillance programs to detect viral hepatitis were expanded to many facilities other than hospitals, including, antenatal care units, prisons, dialysis units and patients requiring frequent medical intervention[38].

Promoting infection control practices to reduce viral hepatitis transmission: Viral hepatitis transmission in Egypt is largely related to improper infection control practice during various medical procedures as; dental, obstetric, injection administration and blood transfusion[23,40,41].

In 2002, MOH, NAMRU-3, and WHO developed a plan to establish an organizational infection control (IC) program structure, develop IC guidelines, train health care workers (HCWs), promote occupational safety, and establish a system for monitoring and evaluating IC activities in Egypt[42]. The plan implementation was assessed in 2011, denoting improved infection control practice, HCWs compliance and substantial reduction in iatrogenic HCV transmission[38].

Improving blood safety to reduce viral hepatitis transmission: Blood transfusion services providers should implement strict measures to ensure blood safety[38]. Special precautions should be followed in hemodialysis centers; HCV patients should use certain hemodialysis instruments other than those used for non-infected individuals, healthcare providers should wear protective gloves while dealing with HCV patients and the hemodialysis instruments[43].

HCV vaccine: HCV vaccine is an important research issue. Two promising studies are in progress; one by GlaxoSmithKline and another that was launched in March 2011 as a clinical trial by National Liver Institute, Menofyia University, Egypt[44].

Secondary prevention

Early detection and treatment of HCV patients is the goal of Egypt’s treatment program starting in 2014, intending HCV prevalence reduction to < 2% in 10 years, in line with global targets. In addition, Egypt has aimed to treat 250000 people annually up to 2020 in the first phase of their treatment program[45] aiming at reducing the number of viremic patients, thus limiting the ongoing HCV transmission.

With the availability of DAAs, Egypt is struggling to eliminate HCV and HCV-related morbidity by 2030[46].

COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATION IN HCV BATTLE

Considering the high prevalence of HCV infection in Egypt, many interventions are required to limit HCV. The first and the most important step is to stop transmission. Shaving at barbershops is a known risk factor for transmission of both HCV and HBV infections[47]. Targeted educational programs on the importance of equipment sterilization are promoted[48].

As illiteracy was known to be a risk factor for HCV transmission in Egypt, the endorsement of health education about the usage of single-use syringes, screening, and treatment of the diagnosed patients decreased the transmission rate and HCV-related complications[49]. Education program directed to awareness about infection risks due to having sex with multiple partner and IV drug use, and precautions to reduce infection transmission by single needle use and cleaning the injection site[50,51].

Among dialysis patients, the annual HCV incidence rate was 28% in 2001. The introduction of IC practices by the MOH resulted in a major decline in this percentage to 6% in 2012[52].

Recently, Information Education Communication had attempts to increase awareness about viral hepatitis in Egypt through, hotlines for counseling, universities vaccination campaign and World Hepatitis Day celebration. World Hepatitis Day celebration meant to bring all stakeholders together and convey an important message to the community. Stakeholders shared in policy making and implementation of action plan[38].

SCREENING PROGRAMS

Most HCV infected patients are unaware of being infected until they develop hepatic cirrhosis[53,54]. Egypt has high HCV transmission rate with around 416000 new infections each year[55], related to self-sustained spread of infection; each HCV patient can transmit the infection to 3.54 subjects[56].

Screening programs helps to identify asymptomatic HCV patients to benefit from early treatment and counseling programs to maintain their health by avoiding high-risk behaviors and awareness about self-protection and prevention of further HCV spread in the community[55].

Due to the unavailability of HCV vaccine as well as the estimated large number of current and ongoing infections, the preventive measures, namely screening, should be prioritized at the same level as the treatment campaigns[57].

In 2008, the Egyptian Demographic Health Survey reported HCV antibody prevalence of 14.7%. The study sample included 11126 women and men aged 15-59 years. It was the first nationwide representative sample for anti-HCV testing performed in Egypt. The blood samples were tested by a third-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect the anti-HCV antibody. Sera positive for anti-HCV antibodies were tested for HCV RNA[9]. This was followed by another screening in 2015[11].

Similar to other developing countries with a high HCV disease burden, Egypt has limited funds to support large-scale prevention programs. Therefore, prioritizing prevention activities, such as screening programs, through specific high-risk groups are essential[58].

In the past, blood transfusion or transfusion of other blood products was a major risk factor for HCV infection. In some historic cohorts, ≥ 10% of the patients who received blood transfusions were infected with hepatitis C[59]. However, since the early 1990s, blood donor screening for HCV has nearly eliminated this transmission route. Several studies conducted on Egyptian blood donors have shown higher prevalence of HCV among paid blood donors and family replacement blood donors than among voluntary donors[60,61]. Further, male donors had a higher prevalence of HCV than females[62], and blood donors from rural areas had a higher prevalence than those from urban areas[63].

Some other screening studies were specifically conducted on children, spouses, and family contacts of HCV-infected patients in Egypt[64-66]. In one such study, the HCV prevalence among spouses of infected patients was as high as 35.5%[67]. In another study, the prevalence among family contacts of infected patients was found to be 5.7%[68].

Screening among hospitalized and special clinic populations revealed elevated HCV prevalence among individuals receiving even minor medical care procedures in and outside established health care facilities[69].

Studying the prevalence of HCV exposure among HCWs, would give us data on the priority treatment and prevention of HCV in Egypt. Several studies were conducted among populations in select HCV-relevant professions[70-73]. The anti-HCV prevalence among HCWs worldwide ranges from 0% to 9.7%[71]. This is comparable with that of the general populations of the same country[72,73]. For example, in 2008, a cross-sectional study performed on 1770 HCWs at Cairo found the anti-HCV prevalence to be 8%[74]. This was comparable to the anti-HCV prevalence in the general populations of Cairo governorate in 2008[9]. Moreover, it was approximately similar to that (7.39%) in general populations of rural Lower Egypt governorates[11]. The high anti-HCV prevalence among Egyptian HCWs and their importance as a source for transmitting HCV suggests mass screening of all HCWs dealing with infectious secretions or tissues and those performing exposure-prone procedures.

LIMITATIONS FOR HCV ELIMINATION

Being an economically constrained country, budget limitation is the main challenge for HCV elimination in Egypt. HCV elimination challenge lies not only in the costs of treatment but also in the costs of diagnosis. Most patients remain undiagnosed and are therefore not appropriately managed. Inadequate diagnosis relates to investigation cost and the high illiteracy rates and low HCV awareness among the general population about the transmission modes and high-risk behaviors[75]. Hence, the majority of infected individuals in Egypt are unaware of their infected status. To achieve 2030 disease elimination target, the number of newly diagnosed patients annually must exceed 350000/year together with a decrease in the incidence of new cases by > 20% annually[76].

Coordination of all efforts is needed to train health care personnel, to deliver efficient care, counseling, and treatment to patients with chronic HCV in accordance with the national and international guidelines.

IC is another limitation to HCV elimination in Egypt. The overall IC had been assessed. In 2003, the overall IC score was 19. In response, the Egyptian MOH launched an IC program to promote safe practices in hospitals and health care facilities. This increased the overall IC score to 68.9 in 2011. However, Egypt still lacks formal IC programs in many health care facilities, professional health care workers with training or expertise in IC, and adequate equipment sterilization, reprocessing practices, and waste management. Limiting the ongoing HCV transmission in Egypt necessitates wider application of IC standards to all health and dental care providers beyond MOH facilities as well as increasing the community awareness.

Until recently, only 40% of HCV-infected individuals were enrolled in government programs for HCV eradication, whereas the HCV treatment expenditure for the remaining 60% individuals comes from Health Insurance Organization, insurance companies, and private payments[77]. Currently, the MOH financially sponsors the treatment for all patients who are not covered by health insurance[17]. Local pharmaceutical companies provide generic versions so as to make DAAs more available for individuals who cannot be treated through governmental schemes. In this context, the national health surveys in Egypt need to be expanded to make all infected individuals aware of their infection status so that they can seek treatment.

FUTURE PROSPECTIVE FOR HCV ELIMINATION

Elimination of an ongoing nightmare like HCV is a national and global dream because of its burden on all aspects of life. Such a dream comes with its future perspectives. We plan to build centers for controlling and treating HCV as nuclei for integrated multidisciplinary centers for liver disease management and screening of treated patients for HCC and centers of excellence for HCC treatment as well as liver transplantation.

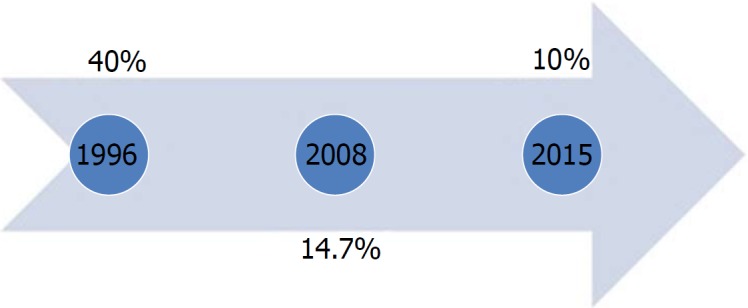

To date, deceased donor liver transplantation has not been implemented in any treatment center program despite law approval by the Egyptian Parliament in 2010. The current practice of living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is the only choice to save many lives and is implemented in nearly 13 centers, with an increase in the total number of LDLT cases to approximately 2400 with improving results[78]. HCC incidence is increasing worldwide. Globally, it is considered the second cause of cancer-related death[79,80]. To date, in Egypt, HCC is known to be the second most common cancer in men and the sixth most common cancer in women, and unfortunately, no current program has yet been implemented for early detection and management of such cases[81]. However, it does not seem like a national dilemma as a Canadian study stated that most HCC cases referred to tertiary treatment centers are in palliative stages[82]. Therefore, because of the obvious advantages of early intervention in HCC, surveillance measures with early detection seem to be the only plausible option. In our experience, HCC developing after chronic hepatitis C treatment with DAAs showed a more infiltrative pattern of lesions[83]. However, the possible role of DAAs in HCC development needs to be further studied to verify the assumption and to identify the possible associated factors. Currently, we are endorsing a surveillance program for patients who have completed DAA therapies in Egypt. This surveillance program is based on the recall of all patients regardless of their fibrosis stage. Such patients will be subjected to abdominal ultrasound and serum alpha fetoprotein measurement every 6 mo (Figure 3). In Egypt, we aim to implement a long-term follow-up and screening program for our HCV patients so that such treatment centers also function as early detection centers for HCC. Such a program would encourage the government to implement therapeutic options for the early detected cases of HCC with higher success rates simultaneously with the running program for HCV eradication. Such an accomplishment will create centers of excellence targeting all HCV-related complications with radical therapeutic options.

Figure 3.

Management of hepatitis C virus patients in Egyptian viral hepatitis treatment centers. DAAs: Direct acting antivirals.

All scientific breakthroughs were originally dreams, followed by future perspective plans and program implementation; we are surely dedicated and insistent on creating such a new breakthrough.

CONCLUSION

The high prevalence of HCV infection in Egypt, which is considered the highest worldwide, prompted the launch of Egypt’s pioneering experience against HCV, aiming to eradicate viral hepatitis by 2030. The strategic plan targeted both treatment and prevention of new transmissions. The introduction of DAAs is a milestone in HCV eradication plan, with SVR rate of almost 100% obtained using certain DAA combinations. Preventing new transmissions is a real challenge that requires collaborative efforts to increase population awareness about transmission modes, safe practices, and importance of screening and early diagnosis. The battle against HCV presented a huge financial burden on Egypt as it is a resource-limited country. It was difficult to provide funding sources to the HCV eradication program as only 40% of the HCV-infected individuals are enrolled in government programs for HCV eradication, whereas the HCV treatment expenditure for the remaining 60% individuals comes from Health Insurance Organization, insurance companies, and private out-of-pocket spending. Fortunately, funds were secured from the governmental support funds issued to individuals who are not under the umbrella of health insurance, and a large number of patients achieved SVR. Egypt provides a role model in planning and implementing the life-long goal of viral hepatitis eradication, which can be implemented in other countries to copy the Egyptian campaign target “For a world free of hepatitis C.”

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Peer-review started: March 27, 2018

First decision: April 3, 2018

Article in press: October 5, 2018

P- Reviewer: Inoue K, Sazci A, Shimizu Y S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

Contributor Information

Dalia Omran, Department of Endemic Medicine and Hepatology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo 11651, Egypt. daliaomran@kasralainy.edu.eg.

Mohamed Alboraie, Department of Internal Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo 11651, Egypt.

Rania A Zayed, Department of Clinical and Chemical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo 11651, Egypt.

Mohamed-Naguib Wifi, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo 11599, Egypt.

Mervat Naguib, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo 11599, Egypt.

Mohamed Eltabbakh, Department of Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo 11566, Egypt.

Mohamed Abdellah, Department of Internal Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo 11651, Egypt.

Ahmed Fouad Sherief, Department of Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo 11566, Egypt.

Sahar Maklad, National Hepatology and Tropical Medicine Research Institute, Cairo 11599, Egypt.

Heba Hamdy Eldemellawy, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef 62511, Egypt.

Omar Khalid Saad, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo 11566, Egypt.

Doaa Mohamed Khamiss, Department of Clinical and Chemical Pathology, El-monera hospital, Ministry of Health, Cairo 11562, Egypt.

Mohamed El Kassas, Department of Endemic Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Helwan University, Cairo 11599, Egypt.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) 2016. Hepatitis C Fact sheet. July. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmonds P, Alberti A, Alter HJ, Bonino F, Bradley DW, Brechot C, Brouwer JT, Chan SW, Chayama K, Chen DS. A proposed system for the nomenclature of hepatitis C viral genotypes. Hepatology. 1994;19:1321–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, Muerhoff AS, Rice CM, Stapleton JT, Simmonds P. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology. 2014;59:318–327. doi: 10.1002/hep.26744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, Brown A, Cooke GS, Pybus OG, Barnes E. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61:77–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.27259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:161–176. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kouyoumjian SP, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. Characterizing hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Egypt: systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1661. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17936-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao MR, Naficy AB, Darwish MA, Darwish NM, Schisterman E, Clemens JD, Edelman R. Further evidence for association of hepatitis C infection with parenteral schistosomiasis treatment in Egypt. BMC Infect Dis. 2002;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Aziz F, Habib M, Mohamed MK, Abdel-Hamid M, Gamil F, Madkour S, Mikhail NN, Thomas D, Fix AD, Strickland GT, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in a community in the Nile Delta: population description and HCV prevalence. Hepatology. 2000;32:111–115. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.8438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Zanaty F, Way A. Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Egyptian: Ministry of Health. Cairo: El-Zanaty and Associates and Macro International;; 2009. p. 31. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR220/FR220.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health and Population/Egypt, El-Zanaty and Associates/Egypt, and ICF International. 2015. Egypt Health Issues Survey 2015. Cairo, Egypt: Ministry of Health and Population/EgyptandICFInternational. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR313/FR313.pdf.

- 11.Kandeel A, Genedy M, El-Refai S, Funk AL, Fontanet A, Talaat M. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt 2015: implications for future policy on prevention and treatment. Liver Int. 2017;37:45–53. doi: 10.1111/liv.13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esmat G. Hepatitis C in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19:587–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alazawi W, Cunningham M, Dearden J, Foster GR. Systematic review: outcome of compensated cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:344–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Bank Health Expenditure, Total (% of GDP) Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS.

- 15.Wedemeyer H, Duberg AS, Buti M, Rosenberg WM, Frankova S, Esmat G, Örmeci N, Van Vlierberghe H, Gschwantler M, Akarca U, et al. Strategies to manage hepatitis C virus (HCV) disease burden. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21 Suppl 1:60–89. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estes C, Abdel-Kareem M, Abdel-Razek W, Abdel-Sameea E, Abuzeid M, Gomaa A, Osman W, Razavi H, Zaghla H, Waked I. Economic burden of hepatitis C in Egypt: the future impact of highly effective therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:696–706. doi: 10.1111/apt.13316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Akel W, El-Sayed MH, El Kassas M, El-Serafy M, Khairy M, Elsaeed K, Kabil K, Hassany M, Shawky A, Yosry A, et al. National treatment programme of hepatitis C in Egypt: Hepatitis C virus model of care. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:262–267. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doss W, Mohamed MK, Esmat G, El Sayed M, Fontanet A, Cooper S, El Sayed N. 2008. Egyptian National Control Strategy for Viral Hepatitis 2008-2012. Arab Republic of Egypt, Ministry of Health and Population, National Committee for the Control of Viral Hepatitis. Available from: http://www.hepnile.org/images/stories/doc/NSP_10_April_2008_final2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esmat G, El Kassas M. 2017. The control of HCV in Egypt. Hepatitis B and C Public Policy Association Newsletter; pp. 4–5. Available from: http://www.hepbcppa.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/06/HepBC-June17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomaa A, Allam N, Elsharkawy A, El Kassas M, Waked I. Hepatitis C infection in Egypt: prevalence, impact and management strategies. Hepat Med. 2017;9:17–25. doi: 10.2147/HMER.S113681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Raziky M, Fathalah WF, El-Akel WA, Salama A, Esmat G, Mabrouk M, Salama RM, Khatab HM. The Effect of Peginterferon Alpha-2a vs. Peginterferon Alpha-2b in Treatment of Naive Chronic HCV Genotype-4 Patients: A Single Centre Egyptian Study. Hepat Mon. 2013;13:e10069. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruane PJ, Ain D, Stryker R, Meshrekey R, Soliman M, Wolfe PR, Riad J, Mikhail S, Kersey K, Jiang D, et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic genotype 4 hepatitis C virus infection in patients of Egyptian ancestry. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1040–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doss W, Shiha G, Hassany M, Soliman R, Fouad R, Khairy M, Samir W, Hammad R, Kersey K, Jiang D, et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treating Egyptian patients with hepatitis C genotype 4. J Hepatol. 2015;63:581–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elsharkawy A, Fouad R, El Akel W, El Raziky M, Hassany M, Shiha G, Said M, Motawea I, El Demerdash T, Seif S, et al. Sofosbuvir-based treatment regimens: real life results of 14 409 chronic HCV genotype 4 patients in Egypt. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:681–687. doi: 10.1111/apt.13923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Kassas M, Alboraie M, Omran D, Salaheldin M, Wifi MN, ElBadry M, El Tahan A, Ezzat S, Moaz E, Farid AM, et al. An account of the real-life hepatitis C management in a single specialized viral hepatitis treatment centre in Egypt: results of treating 7042 patients with 7 different direct acting antiviral regimens. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1476137. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed OA, Elsebaey MA, Fouad MHA, Elashry H, Elshafie AI, Elhadidy AA, Esheba NE, Elnaggar MH, Soliman S, Abd-Elsalam S. Outcomes and predictors of treatment response with sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir with or without ribavirin in Egyptian patients with genotype 4 hepatitis C virus infection. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:441–445. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S160593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abd-Elsalam S, Sharaf-Eldin M, Soliman S, Elfert A, Badawi R, Ahmad YK. Efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of cirrhotic patients with genotype 4 hepatitis C virus in real-life clinical practice. Arch Virol. 2018;163:51–56. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3573-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Kassas M, Omran D, Elsaeed K, Alboraie M, Elakel W, El Tahan A, Abd El Latif Y, Nabeel MM, Korany M, Ezzat S, et al. Spur-of-the-Moment Modification in National Treatment Policies Leads to a Surprising HCV Viral Suppression in All Treated Patients: Real-Life Egyptian Experience. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2018;38:81–85. doi: 10.1089/jir.2017.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Khayat HR, Fouad YM, Maher M, El-Amin H, Muhammed H. Efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir plus simeprevir therapy in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C: a real-world experience. Gut. 2017;66:2008–2012. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eletreby R, Elakel W, Said M, El Kassas M, Seif S, Elbaz T, El Raziky M, Abdel Rehim S, Zaky S, Fouad R, et al. Real life Egyptian experience of efficacy and safety of Simeprevir/Sofosbuvir therapy in 6211 chronic HCV genotype IV infected patients. Liver Int. 2017;37:534–541. doi: 10.1111/liv.13266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdel-Moneim A, Aboud A, Abdel-Gabaar M, Zanaty MI, Ramadan M. Efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir with or without ribavirin: large real-life results of patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. Hepatol Int. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12072-018-9868-8. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Khayat H, Fouad Y, Mohamed HI, El-Amin H, Kamal EM, Maher M, Risk A. Sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir with or without ribavirin in 551 patients with hepatitis C-related cirrhosis, genotype 4. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:674–679. doi: 10.1111/apt.14482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohamed MS, Hanafy AS, Bassiony MAA, Hussein S. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir plus ribavirin treatment improve liver function parameters and clinical outcomes in Egyptian chronic hepatitis C patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1368–1372. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omar H, El Akel W, Elbaz T, El Kassas M, Elsaeed K, El Shazly H, Said M, Yousif M, Gomaa AA, Nasr A, et al. Generic daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, in treatment of chronic hepatitis C: real-world results from 18 378 patients in Egypt. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:421–431. doi: 10.1111/apt.14428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Khayat HR, Kamal EM, El-Sayed MH, El-Shabrawi M, Ayoub H, RizK A, Maher M, El Sheemy RY, Fouad YM, Attia D. The effectiveness and safety of ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir in adolescents with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection: a real-world experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:838–844. doi: 10.1111/apt.14502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elsharkawy A, El-Raziky M, El-Akel W, El-Saeed K, Eletreby R, Hassany M, El-Sayed MH, Kabil K, Ismail SA, El-Serafy M, et al. Planning and prioritizing direct-acting antivirals treatment for HCV patients in countries with limited resources: Lessons from the Egyptian experience. J Hepatol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attia D, El Saeed K, Elakel W, El Baz T, Omar A, Yosry A, Elsayed MH, Said M, El Raziky M, Anees M, et al. The adverse effects of interferon-free regimens in 149 816 chronic hepatitis C treated Egyptian patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:1296–1305. doi: 10.1111/apt.14538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wanis H, Hussein A, El Shibiny A, et al. 2014. HCV treatment in Egypt - why cost remains a challenge Egyptian initiative for personal rights; pp. 6–18. Available from: http://www.eipr.org/sites/default/files/pressreleases/pdf/hcv_treatment_in_egypt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medhat A, Shehata M, Magder LS, Mikhail N, Abdel-Baki L, Nafeh M, Abdel-Hamid M, Strickland GT, Fix AD. Hepatitis c in a community in Upper Egypt: risk factors for infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:633–638. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mostafa A, Taylor SM, el-Daly M, el-Hoseiny M, Bakr I, Arafa N, Thiers V, Rimlinger F, Abdel-Hamid M, Fontanet A, et al. Is the hepatitis C virus epidemic over in Egypt? Incidence and risk factors of new hepatitis C virus infections. Liver Int. 2010;30:560–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talaat M, Radwan E, El-Sayed N, Ismael T, Hajjeh R, Mahoney FJ. Case-control study to evaluate risk factors for acute hepatitis B virus infection in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talaat M, el-Oun S, Kandeel A, Abu-Rabei W, Bodenschatz C, Lohiniva AL, Hallaj Z, Mahoney FJ. Overview of injection practices in two governorates in Egypt. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:234–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagan H, Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Purchase D, Alter MJ. Reduced risk of hepatitis B and hepatitis C among injection drug users in the Tacoma syringe exchange program. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1531–1537. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.11.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdel-Ghaffar TY, Sira MM, El Naghi S. Hepatitis C genotype 4: The past, present, and future. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2792–2810. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i28.2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gamal E. 2014. Situation of HCV in Egypt Towards an End to HCV Epidemic. Available from: http://www.liver-eg.org/assets/esmatt-hepatitis-c-situation-in-egypt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayoub HH, Abu-Raddad LJ. Impact of treatment on hepatitis C virus transmission and incidence in Egypt: A case for treatment as prevention. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:486–495. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paez Jimenez A, El-Din NS, El-Hoseiny M, El-Daly M, Abdel-Hamid M, El Aidi S, Sultan Y, El-Sayed N, Mohamed MK, Fontanet A. Community transmission of hepatitis B virus in Egypt: results from a case-control study in Greater Cairo. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:757–765. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metwally A, Mohsen A, Saleh R, Foaud W, Ibrahim N, Rabaah T, El-Sayed M. Prioritizing High-Risk Practices and Exploring New Emerging Ones Associated With Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Egypt. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:1385–1394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guerra J, Garenne M, Mohamed MK, Fontanet A. HCV burden of infection in Egypt: results from a nationwide survey. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:560–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dolan K, MacDonald M, Silins E, Topp L. Needle and syringe programs: A review of the evidence. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2005. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/.../$File/evid.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Islam MM, Topp L, Conigrave KM, Haber PS, White A, Day CA. Sexually transmitted infections, sexual risk behaviours and perceived barriers to safe sex among drug users. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37:311–315. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Progress toward prevention and control of hepatitis C virus infection--Egypt, 2001-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calès P, Boursier J, Bertrais S, Oberti F, Gallois Y, Fouchard-Hubert I, Dib N, Zarski JP, Rousselet MC; multicentric groups (SNIFF 14 & 17, ANRS HC EP 23 Fibrostar) Optimization and robustness of blood tests for liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:1315–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen LH, Nguyen MH. Systematic review: Asian patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:921–936. doi: 10.1111/apt.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kandeel AM, Talaat M, Afifi SA, El-Sayed NM, Abdel Fadeel MA, Hajjeh RA, Mahoney FJ. Case control study to identify risk factors for acute hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Breban R, Arafa N, Leroy S, Mostafa A, Bakr I, Tondeur L, Abdel-Hamid M, Doss W, Esmat G, Mohamed MK, et al. Effect of preventive and curative interventions on hepatitis C virus transmission in Egypt (ANRS 1211): a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e541–e549. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Hepatitis C screening. USPSTF. 2013. Available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/Recommendation Statement Final/hepatitis-c-screening.

- 58.Artenie AA, Bruneau J, Lévesque A, Wansuanganyi JM. Role of primary care providers in hepatitis C prevention and care: one step away from evidence-based practice. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:881–882, e468-e470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alter HJ, Purcell RH, Shih JW, Melpolder JC, Houghton M, Choo QL, Kuo G. Detection of antibody to hepatitis C virus in prospectively followed transfusion recipients with acute and chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1494–1500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911303212202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elkareh S. HCV screening of donors in Governmental Blood Transfusion Centers at Menoufia Governorate (from Jan. 2008 to Oct. 2008) Vox Sang. 2009;96:89–90. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eita N. Prevalence of HCV and HBV infections among blood donors in Dakahilia, Egypt. Vox Sang. 2009;96:106–107. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rushdy O, Moftah F, Zakareya S. Trasmitted transfused viral infections among blood donors during years 2006 and 2007 in suez canal area, Egypt. Vox Sang. 2009;96:86–87. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arthur RR, Hassan NF, Abdallah MY, el-Sharkawy MS, Saad MD, Hackbart BG, Imam IZ. Hepatitis C antibody prevalence in blood donors in different governorates in Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:271–274. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El-Sherbini A, Hassan W, Abdel-Hamid M, Naeim A. Natural history of hepatitis C virus among apparently normal schoolchildren: follow-up after 7 years. J Trop Pediatr. 2003;49:384–385. doi: 10.1093/tropej/49.6.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mohamed MK, Magder LS, Abdel-Hamid M, El-Daly M, Mikhail NN, Abdel-Aziz F, Medhat A, Thiers V, Strickland GT. Transmission of hepatitis C virus between parents and children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El Sherbini A, Mohsen SA, Hasan W, Mostafa S, El Gohary K, Moneib A, Abaza AH. The peak impact of an Egyptain outbreak of hepatitis C virus: has it passed or has not yet occurred? Liver Int. 2007;27:876–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morad WS. Transmission of hepatitis C between spouses an epidemiological study at National Liver Institute hospital. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:S81. [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Zayadi A, Khalifa AA, El-Misiery A, Naser AM, Dabbous H, Aboul-Ezz AA. Evaluation of risk factors for intrafamilial transmission of HCV infection in Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1997;72:33–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mohamoud YA, Mumtaz GR, Riome S, Miller D, Abu-Raddad LJ. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Egypt: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shalaby S, Kabbash IA, El Saleet G, Mansour N, Omar A, El Nawawy A. Hepatitis B and C viral infection: prevalence, knowledge, attitude and practice among barbers and clients in Gharbia governorate, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coppola N, De Pascalis S, Onorato L, Calò F, Sagnelli C, Sagnelli E. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection in healthcare workers. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:273–281. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i5.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arguillas MO, Domingo EO, Tsuda F, Mayumi M, Suzuki H. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in the Philippines: a preliminary study and comparison with hepatitis B virus infection among blood donors, medical personnel, and patient groups in Davao, Philippines. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1991;26 Suppl 3:170–175. doi: 10.1007/BF02779292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ozsoy MF, Oncul O, Cavuslu S, Erdemoglu A, Emekdas G, Pahsa A. Seroprevalences of hepatitis B and C among health care workers in Turkey. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:150–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okasha O, Munier A, Delarocque-Astagneau E, El Houssinie M, Rafik M, Bassim H, Hamid MA, Mohamed MK, Fontanet A. Hepatitis C virus infection and risk factors in health-care workers at Ain Shams University Hospitals, Cairo, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;21:199–212. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS) 2013. Poverty indicators according to income, expenditure and consump¬tion data 2012-2013. Available from: http://www.capmas.gov.eg/pepo/a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Waked I, Doss W, El-Sayed MH, Estes C, Razavi H, Shiha G, Yosry A, Esmat G. The current and future disease burden of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2014;15:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iskander D. The Right to Health: a case study on Hepatitis C in Egypt. MS.c. thesis, American University in Cairo. 2013. Available from: URL: https://dar.aucegypt.edu/bitstream/handle/10526/3748/Thesis%20IHRL%20%20Dina%20Iskander%20Dec2013.pdf?sequence=3. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amer KE, Marwan I. Living donor liver transplantation in Egypt. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2016;5:98–106. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2015.10.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.World Health Organization. Mortality database. WHO statistical information system. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis.

- 80.Venook AP, Papandreou C, Furuse J, de Guevara LL. The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective. Oncologist. 2010;15 Suppl 4:5–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Egyptian National Cancer Registry. Available from: http://www.cancerregistry.gov.eg.

- 82.Khalili K, Menezes R, Yazdi LK, Jang HJ, Kim TK, Sharma S, Feld J, Sherman M. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a large Canadian urban centre: stage at treatment and its potential determinants. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:150–154. doi: 10.1155/2014/561732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Abdelaziz AO, Nabil MM, Abdelmaksoud AH, Shousha HI, Cordie AA, Hassan EM, Omran DA, Leithy R, Elbaz TM. De-novo versus recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma following direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:39–43. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]