Abstract

Context:

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most important prognostic factors are age, leukocyte count at presentation, immunophenotype, and cytogenetic abnormalities. The cytogenetic abnormalities are associated with distinct immunologic phenotypes of ALL and characteristic outcomes.

Aims:

The present study was primarily aimed at analyzing the impact of cytogenetics on postinduction responses and event-free survival (EFS) in pediatric patients with ALL. The secondary objective was to study the overall survival (OS).

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 240 patients with age <18 years and diagnosed with ALL between January 2011 and June 2016 were retrospectively analyzed. Cytogenetics was evaluated with conventional karyotyping or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Based on cytogenetic abnormalities, the patients were grouped into five categories, and the outcomes were analyzed.

Results:

Of the 240 patients, 125 (52%) patients had evaluable cytogenetics. Of these, 77 (61.6%) patients had normal cytogenetics, 19 (15.2%) had t(9;22) translocation, 10 (8%) had unfavorable cytogenetics which included t(9;11), hypodiploidy, and complex karyotype, 10 (8%) had favorable cytogenetics which included t(12;21), t(1;19), and high hyperdiploidy, 9 (7.2%) had miscellaneous cytogenetics. Seventy-one percent of patients were treated with MCP 841 protocol, while 29% of patients received BFM-ALL 95 protocol. The 3-year EFS and OS of the entire group were 52% and 58%, respectively. On univariate analysis, EFS and OS were significantly lower in t(9;22) compared to normal cytogenetics (P = 0.033 and P = 0.0253, respectively) and were not significant for other subgroups compared to normal cytogenetics. On multivariate analysis, EFS was significantly lower for t(9;22) and unfavorable subgroups.

Conclusions:

Cytogenetics plays an important role in the molecular characterization of ALL defining the prognostic subgroups. Patients with unfavorable cytogenetics and with t(9;22) have poorer outcomes.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, cytogenetics, event-free survival, overall survival, pediatric

Introduction

In the past two decades, survival rates for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had drastically improved, with an estimated 5-year overall survival (OS) rate >85% in the Western population.[1] However, the survival rates in developing countries are still lower reporting between 30% and 70%.[2]

The most important prognostic factors affecting survival are age, white blood cell (WBC) count, immunophenotyping, and cytogenetics. Various cytogenetic studies and molecular analysis revealed a great number of recurring cytogenetic abnormalities in pediatric ALL. Not only is the frequency of cytogenetic abnormalities lower in adults but even there is a difference in the prevalence of the various abnormalities. These cytogenetic abnormalities are associated with distinct immunologic phenotypes of ALL and characteristic outcomes.[3] The recent WHO classification of acute leukemias incorporated these cytogenetic abnormalities.[4]

Based on the treatment failures and outcomes, the most frequent cytogenetic alterations have been grouped into unfavorable and favorable subgroups.[5] In the present study, we analyzed the impact of cytogenetics on outcomes in pediatric patients with ALL with respect to postinduction response, event-free survival (EFS), and OS.

Subjects and Methods

Data of patients with ALL aged ≤18 years, diagnosed between January 2011 and June 2016, were retrospectively analyzed. Clinical and hematological parameters regarding age, gender, hemoglobin, WBC count, platelet count, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), bone marrow blasts, and B- or T-lineage were collected and analyzed. Induction chemotherapy regimens used for remission induction were MCP 841 protocol and BFM 95 ALL protocols,[6,7] and postinduction response was evaluated based on day 33 marrow and further therapy was continued according to the protocol and response evaluation.

Bone marrow samples collected at the time of diagnoses were analyzed for cytogenetics. Conventional karyotyping and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were used to analyze the cytogenetic aberrations. RT-PCR was used to identify the cytogenetic abnormalities such as t(9;22), t(4;11), t(9;11), t(12;21), and t(1;19). Those patients without evaluable cytogenetics were excluded from the study.

Based on these cytogenetic alterations, patients were grouped into five categories. These include: (1) Ph + (t[9;22]), (2) unfavorable cytogenetics which include t(4;11), t(9;11), hypodiploidy, and complex karyotyping (more than three chromosomal aberrations), (3) favorable cytogenetics which include t(12;21), t(1;19), and high hyperdiploidy, (4) normal cytogenetics, and (5) miscellaneous which included those aberrations with no documented prognostic significance.

These groups were then analyzed for postinduction response, EFS, and OS. Postinduction response evaluation was done on day 33 marrow and the patients categorized into complete remission (CR, <5% blasts), partial remission (PR, 5%–20% blasts), and persistence of disease (>20% blasts). EFS was defined as the time from CR to the date when relapse, death, and second neoplasms were documented or lost to follow-up. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death due to any cause or lost to follow-up.

Statistical methods

Fisher's exact test using Prism version 7.02, GraphPad software, La Jolla, California, USA, was used to analyze the proportion of mutations depending on the type of failure.[8] To evaluate the association between mutation status and survival, log-rank test was used. Survival probabilities were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test.[9]

Results

A total of 240 patients diagnosed with ALL aged <18 years were evaluated. One hundred and twenty-five patients had evaluable cytogenetics, of which 85 (68%) had B-ALL, 39 (31%) had T-ALL, and 1 (1%) had mixed B and myeloid phenotype. The distribution of patients in each cytogenetic subgroup is 19 (15%), 10 (8%), 10 (8%), 77 (62%), and 9 (7%) in Ph+, unfavorable, favorable subgroups, normal cytogenetics, and miscellaneous subgroups, respectively. The subsets of patients in unfavorable and favorable group are shown in Table 1. Miscellaneous subgroup included patients with t(2;12), t(1;13), trisomy 7, 21, 22, deletion 5, 14, inversion 14, and 47xy aberrations. The baseline characteristics and baseline hematological parameters of all the five subgroups and entire group are summarized in Table 2. The protocols most commonly used in this study were MCP 841 protocol in 89 (71.2%) patients and BFM-ALL 95 protocol in 36 (28.8%). In the subgroups of normal cytogenetics, Ph+, unfavorable, favorable, and miscellaneous, MCP 841 protocol was used in 53, 13, 6, 8, and 9 patients, respectively, and BFM ALL 95 in 24, 6, 4, 2, and zero patients, respectively. Two patients with t(9;22) received concurrent imatinib along with chemotherapy and remaining patients received sequential imatinib.

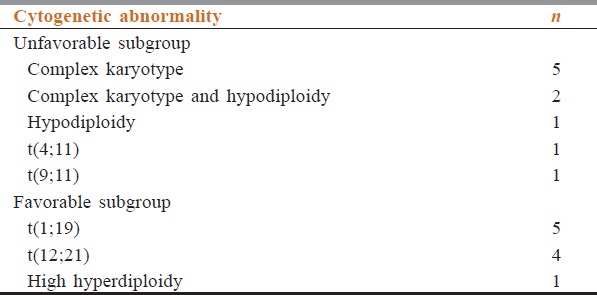

Table 1.

Unfavorable and favorable subgroups

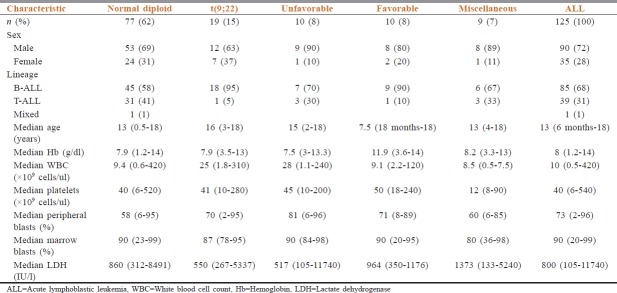

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

Outcomes

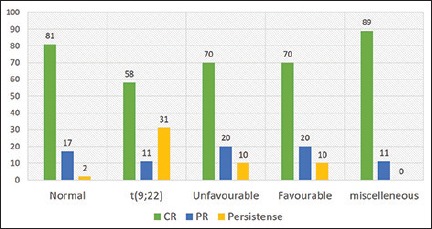

After induction chemotherapy, 94 (75%) of the patients achieved CR, while 21 (17%) had PR, and 10 (8%) had induction failure. Postinduction responses are depicted in [Figure 1. Lower CR rate (58%) and higher induction failure (31%) were seen in t(9;22) positive patients.

Figure 1.

Percentage of postinduction response in the subgroups

Survival outcomes

The 3-year EFS and OS of the entire group (n = 240) were 52% and 58%, respectively.

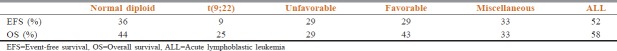

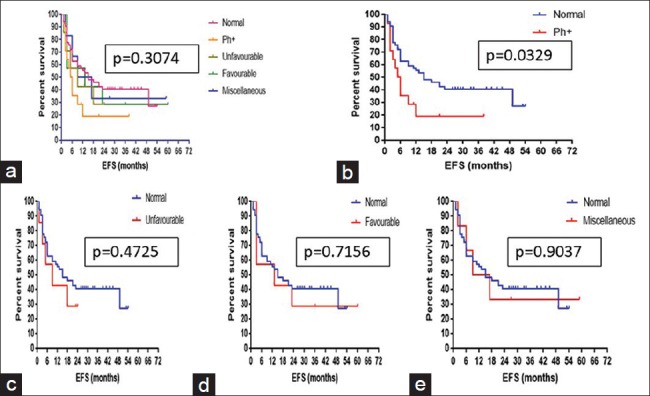

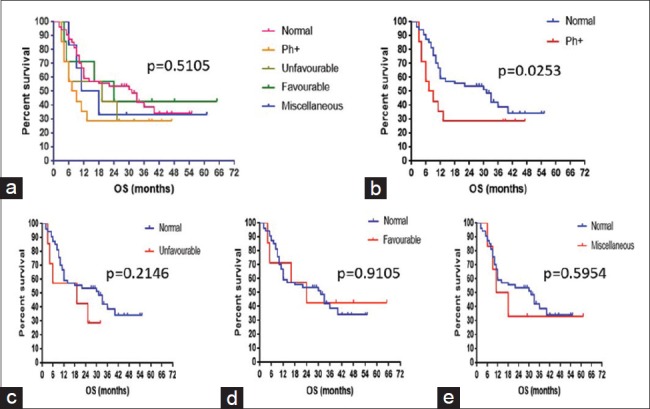

EFS for B-ALL and T-ALL subgroups was 59% and 45% (P = 0.1815), whereas OS was 64% and 49% (P = 0.1755), respectively. The EFS and OS for the cytogenetic subgroups are shown in Table 3 and Figures 2a, 3a, respectively.

Table 3.

Survival outcomes in cytogenetic subgroups

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimate for event free survival of (a) the five cytogenetic subgroups, (b) normal diploid versus t(9;22), (c) normal diploid versus unfavorable, (d) normal diploid versus favorable, (e) normal diploid versus miscellaneous

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimate for overall survival of (a) the five cytogenetic subgroups, (b) normal diploid versus t(9;22), (c) normal diploid versus unfavorable, (d) normal diploid versus favorable, (e) normal diploid versus miscellaneous

On comparing the patients with normal cytogenetics to the other subgroups, EFS was significantly low for t(9;22) group (P = 0.033, hazard ratio = 0.5006) while other subgroups did not have a statistically significant difference in EFS [Figure 2b–e]. Similarly, when OS of the patients with normal cytogenetics was compared with the other groups, it was significantly lower for t(9; 22) subgroup (P = 0.0253, hazard ratio = 0.509) and was not statistically significant for the other subgroups [Figure 3b–e].

On multivariate analysis, EFS remained significantly low for the cytogenetic subgroups of t(9;22) and unfavorable (P = 0.0314) and OS was significantly low with the postinduction response (P = 0.0188), whereas age, gender, median WBC count, median blast percentage, and lineage did not affect either EFS or OS.

Discussion

This is a retrospective study of impact of cytogenetic abnormalities on outcomes in pediatric ALL. The present study comprised 240 pediatric patients with ALL, of which 125 (52%) had evaluable cytogenetics. This was similar to that seen in a study by Fletcher et al. (45.2%) but lower than that observed in a study by Pullarkat et al. (65.5%).[10,11] The median age at presentation was 7.4 and 7.7 years in studies by Pandita et al. and Settin et al., respectively whereas it was higher in our study (13 years, range: 6 months to 18 years).[12,13] Similar to the study by Settin et al. (male:female ratio: 1.73:1), there was higher prevalence of leukemia in boys with a male:female ratio of 2.57:1, but this was different in the study by Pandita et al. there was female prominence (0.8:1).[12,13]

The incidence of B-ALL and T-ALL was 91.6% and 8.3%, 79.5% and 8.6%, and 93.2% and 6.8% in studies by Safaei et al., Chessels et al., and Forestier et al., respectively[14,15,16] In the present study of all patients, 68% had B-ALL and 31% had T-ALL. Although B-ALL predominated in our study, the incidence of T-ALL was higher compared to the other studies.

Of the 125 patients with evaluable cytogenetics, 61.6% of patients had normal diploid phenotype, 15.2% had t(9;22), 8% had unfavorable, another 8% had favorable cytogenetics, and 7% had miscellaneous cytogenetics. t(9;22) though a part of the unfavorable cytogenetic group was studied separately due to the availability of targeted agents, which are a major part of the therapy in these patients. Compared to the other studies by Chessels et al. and Forestier et al., the percentage of normal diploid and t(9;22) was higher in our study, while the incidence of t(4;11) and hypodiploidy was lower in our study.[15,16] Similar percentage of t(9;22) patients was also seen in the study by Pandita et al.[12]

In the five subgroups, the median hemoglobin was higher in the subgroup with favorable cytogenetics (11.9 g/dl), while median WBC count was higher in t(9;22) and unfavorable subgroups (25,000 and 28,000). Median peripheral blasts were also higher in patients with unfavorable subgroup (81%). Miscellaneous group had higher median LDH (1373 IU/L) and lower median platelet count(12,000) compared to other groups.

There was no difference among the subgroups on the basis of the protocols used (MCP 841 or BFM-ALL 95). Two patients with t(9;22) received imatinib along with chemotherapy. Supportive care in the form of intravenous (iv) fluids, blood products, iv antibiotics, and other necessary measures was taken, and the patients were evaluated for postinduction responses and survival.

In the study by Pandita et al., postinduction therapy, six patients had persistence of disease, two each with t(9;22) and t(4;11).[12] Postinduction bone marrow done on day 33 in our study showed CR in 75% of the patients, PR in 17%, and persistence of disease in 8%. Six out of the 10 with persistence of disease had t(9;22) and one patient had t(4;11). None of these patients achieved second remission.

The EFS from various Indian studies by Shanta et al., Radhakrishnan et al., and Advani et al. ranged from 38% to 63.4% but was lower compared to global data in studies by Hunger et al., Chessells et al., and Pui et al., where the EFS ranged from 28% to 85.6% and OS ranged from 37% to 94%.[17,18,19,20,21,22] In our study for the entire group, the 3-year EFS and OS are 52% and 58%, respectively. The 3-year EFS and OS of B-ALL and T-ALL were not statistically different (59% vs. 45%, P = 0.18; 64% vs. 49%, P = 0.175). This was similar to a study by Goldberg et al., which also showed no significant difference in survival between B- and T-ALL (5-year EFS: P = 0.56 and 5-year OS: P =0.10).[23]

In the study by Fletcher et al., there was no significant difference in survival of children with and without structural chromosomal abnormalities.[10] In the study by Chessells et al., EFS was significantly affected by near haploid, hypodiploid, hyperdiploid, t(4;11), t(1;19), t(9;22), and del (11q).[15] In the present study, the EFS and OS were significantly low for the subgroup with t(9;22) (P = 0.03 and P = 0.0253, respectively) while the EFS and OS were not statistically different for other subgroups compared to normal diploid phenotype. The 5-year EFS for t(9;22) patients in various studies ranged from 20% to 25%.[24]

In the studies of adult patients with ALL, t(9;22), t(4;11), t(8;14), and complex karyotype were found to have significant worse outcome, while miscellaneous group had outcomes similar to normal diploid and del (9p) was associated with improved survival.[11,25]

Limitations of the study

The main drawback of this study was that it is a retrospective study. Cytogenetics data were not available for all patients mainly due to inadequate sampling and financial constraints. The poor survival rates might be due to use of less intense protocols such as MCP 841 protocol in majority of patients and lack of allogenic bone marrow transplant at the time of relapse and the insignificant difference in the survival outcomes in the subgroups might be due to the small sample size in the subgroups.

Conclusions

Cytogenetics plays an important role in the molecular characterization of ALL defining the prognostic subgroups. Patients with unfavorable cytogenetics and with t(9;22) positivity have poorer outcomes. Earlier incorporation of targeted agents in patients with t(9;22) positivity may further improve outcomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulkarni KP, Arora RS, Marwaha RK. Survival outcome of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in India: A resource-limited perspective of more than 40 years. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:475–9. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31820e7361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Correlations with hematologic findings outcome. A Collaborative Study of the Group Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique. Blood. 1996;87:3135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the world health organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mrózek K, Harper DP, Aplan PD. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:991–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.07.001. v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magrath I, Shanta V, Advani S, Adde M, Arya LS, Banavali S, et al. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in countries with limited resources; lessons from use of a single protocol in India over a twenty year period [corrected] Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1570–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Möricke A, Reiter A, Zimmermann M, Gadner H, Stanulla M, Dördelmann M, et al. Risk-adjusted therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia can decrease treatment burden and improve survival: Treatment results of 2169 unselected pediatric and adolescent patients enrolled in the trial ALL-BFM 95. Blood. 2008;111:4477–89. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Jolla, California, USA: GraphPad Software; [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 23]. GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Windows. Available from: http://www.graphpad.com . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan EL, Maier P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1965;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher JA, Kimball VM, Lynch E, Donnelly M, Pavelka K, Gelber RD, et al. Prognostic implications of cytogenetic studies in an intensively treated group of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1989;74:2130–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pullarkat V, Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Forman SJ, Appelbaum FR. Impact of cytogenetics on the outcome of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of southwest oncology group 9400 study. Blood. 2008;111:2563–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandita A, Harish R, Digra SK, Raina A, Sharma AA, Koul A, et al. Molecular cytogenetics in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A hospital-based observational study. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2015;9:39–42. doi: 10.4137/CMO.S24463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Settin A, Al Haggar M, Al Dosoky T, Al Baz R, Abdelrazik N, Fouda M, et al. Prognostic cytogenetic markers in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:255–63. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safaei A, Shahryari J, Farzaneh MR, Tabibi N, Hosseini M. Cytogenetic findings of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Fars province. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38:301–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chessels JM, Swansbury GJ, Reeves B, Bailey CC, Richards SM. Cytogenetics and prognosis in childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia: Results of MRC UKALL X. Medical research council working party in childhood leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:93–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3493163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forestier E, Johansson B, Gustafsson G, Borgström G, Kerndrup G, Johannsson J, et al. Prognostic impact of karyotypic findings in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: A Nordic series comparing two treatment periods. For the Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (NOPHO) leukaemia cytogenetic study group. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:147–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanta V, Maitreyan V, Sagar TG, Gajalakshmi CK, Rajalekshmy KR. Prognostic variables and survival in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemias: Cancer institute experience. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;13:205–16. doi: 10.3109/08880019609030819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radhakrishnan V, Gupta S, Ganesan P, Rajendranath R, Ganesan TS, Rajalekshmy KR, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A single center experience with Berlin, Frankfurt, and munster-95 protocol. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2015;36:261–4. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.171552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Advani S, Pai S, Venzon D, Adde M, Kurkure PK, Nair CN, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in India: An analysis of prognostic factors using a single treatment regimen. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:167–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1008366814109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: A report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1663–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chessells JM, Harrison CJ, Kempski H, Webb DK, Wheatley K, Hann IM, et al. Clinical features, cytogenetics and outcome in acute lymphoblastic and myeloid leukaemia of infancy: Report from the MRC childhood leukaemia working party. Leukemia. 2002;16:776–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, Bowman WP, Sandlund JT, Kaste SC, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2730–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg JM, Silverman LB, Levy DE, Dalton VK, Gelber RD, Lehmann L, et al. Childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: The Dana-Farber cancer institute acute lymphoblastic leukemia consortium experience. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3616–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhutani M, Kochupillai V, Bakshi S. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Indian experience. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2004;20:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, Richards SM, Secker-Walker LM, Martineau M, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): Analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial. Blood. 2007;109:3189–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]