Abstract

Erector spinae plane block (ESPB) is a new truncal block which has been used successfully to manage many acute and painful conditions including multiple fractured ribs. This block is primarily an ultrasound-guided block. We have evaluated the feasibility of fluoroscopic guidance for this block. We have reported two cases of severe chest pain due to multiple fractured ribs managed successfully with ESPB given under fluoroscopic guidance.

Key words: Erector spinae plane block, fluoroscopic guided blocks, multiple fractured ribs pain, ultrasound-guided blocks

INTRODUCTION

Erector spinae plane block (ESPB) is an ultrasound-guided truncal block where local anaesthetic is injected below the erector spinae muscle (ESM) between ESM and transverse process (TP) of the vertebra. Forero et al.[1] used this block for the first time to manage a patient with thoracic neuropathic pain. Since then, ESPB has been used to manage many acute and chronic pain conditions.[2,3,4] Seeing the expanding indications and successful use of ESPB, we hypothesised that if ESPB is feasible by fluoroscopy, then this block can be used to its full potential where either ultrasound facility is not available or technical know-how is lacking. Moreover, a pain physician who deals with many chronic pain conditions using fluoroscopic guidance will also use it if indication permits.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

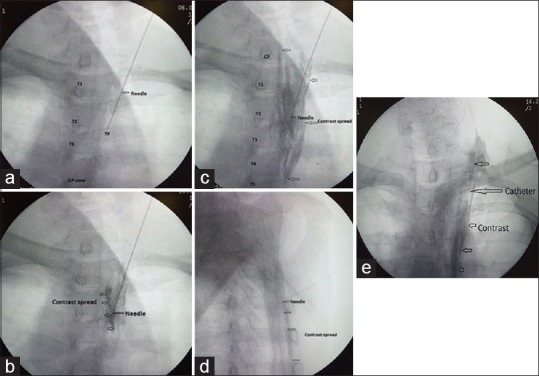

A 39-year-old, 72-kg male patient had multiple fractured ribs (two to six) on the right side due to a fall from a tree. He did not have any other visceral injuries. Initially his pain was managed with intravenous non-steroidal analgesics, tramadol and fentanyl. His resting pain was slightly reduced from 8 to 6 on numeric rating scale (NRS; 0 = no pain and 10 = maximum pain), but pain on deep breathing and coughing was unchanged (9/10 and 10/10). ESPB was planned after informed consent. In the operating room, intravenous access was secured, and noninvasive monitors for pulse, SpO2, and blood pressure were attached. The patient was positioned in prone position. Due to severe pain during positioning, injection fentanyl 25 μg and ketamine 20 mg intravenously were given (the patient remained conscious and was communicating even after sedation). With due aseptic precautions, the injection site was infiltrated with 2 mL of 1% lidocaine, and a 23G spinal needle attached with saline-filled tube was directed toward TP of third thoracic vertebra (T3) under fluoroscopic guidance [Figure 1a]. After contacting the TP, aspiration test was done to avoid inadvertent vascular injection, and then 1 mL mixture of 0.5 mL contrast (Omnipaque-300®) and 0.5 mL saline were injected. A smooth cephalic–caudal spread was noticed [Figure 1b]. A total of 25 mL of mixture (20 mL, 0.25 bupivacaine, and 5 mL contrast) was injected and adequacy of spread was confirmed through anterior–posterior and lateral views [Figure 1c and d]. The needle was removed and the patient was shifted to recovery room. After 15 min, the patient reported significant pain relief (NRS 4/10 on coughing). Taking into account the possible analgesic effect of intravenous sedation, the patient was reassessed after 1, 2, and then 4 h. Cold testing at 2 h showed changes in sensation from T1 to T8 on both anterior and posterior thorax of the right side with patchy sparing near mid clavicular line anteriorly. Pain relief continued for more than 10 h (NRS on deep breathing and coughing remained <5/10). The next day, using the same technique of fluoroscopic guidance, an 18G epidural catheter was inserted through a Tuohy needle; catheter position was confirmed with 2 mL of contrast [Figure 1e] and then continuous infusion of 0.1% bupivacaine at 8 mL/h was started using portable elastomeric pump along with injection paracetamol (1 G intravenous 8 hourly) and injection tramadol (50 mg IV one to two doses/24 h). After 3 days, intravenous analgesics were stopped and oral analgesic (tablet containing paracetamol 325 mg + tramadol 50 mg) 8 hourly was started along with infusion of bupivacaine. After 5 days, the catheter was removed when resting NRS was 0/10 and 1–2/10 on deep breathing and 2–3/10 on coughing. Oral analgesics were continued and the patient was discharged on the next day.

Figure 1.

(a) Needle is touching transverse process of third thoracic level (anterior–posterior view), (b) linear spread of contrast between erector spinae muscle and transverse process (anterior–posterior view), (c) increasing spread of contrast while more volume is being injected (anterior–posterior view), (d) caudal and cephalic spread of contrast near transverse processes (lateral view), and (e) contrast spread through catheter (anterior–posterior view)

Case 2

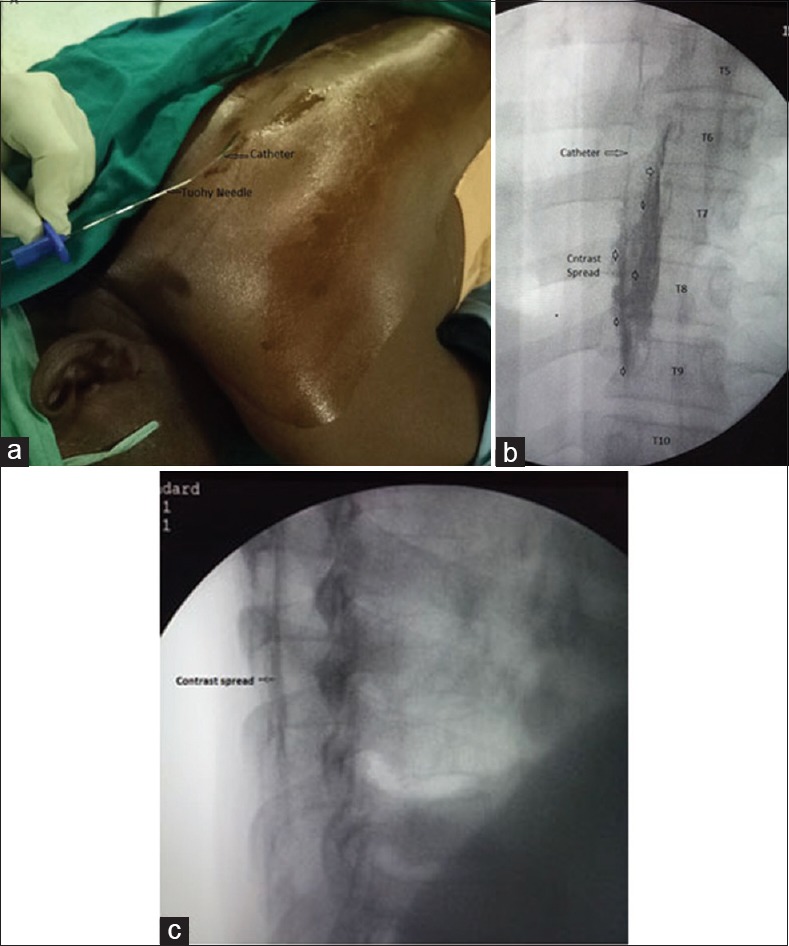

A 51-year-old, 69-kg male patient presented with severe chest pain due to fractured ribs (5th to 10th) posteriorly on the left side following a road traffic accident. NRS on deep breathing was 8/10 and on coughing, 10/10. Similar to previous patient, after informed consent, in prone position and under fluoroscopic guidance, 18G Tuohy needle was inserted and guided toward TP of fifth vertebra on the left side. The correct position was confirmed with 2 mL mixture of saline and contrast. An 18G epidural catheter was inserted through Tuohy needle (catheter tip kept 4 cm beyond the needle tip). The position was confirmed by injection of 5 mL contrast [Figure 2a–c] and 25 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was given through catheter. The patient showed significant relief after 15 min (NRS was 4–5/10 on coughing). Further pain management was similar to previous case except that the patient was discharged on the eighth day.

Figure 2.

(a) An 18G epidural catheter being inserted through Tuohy needle, (b) confirmation of catheter position, contrast spread after catheter insertion (anterior-posterior view), and (c) linear spread of contrast near transverse processes (lateral view)

No complications were observed during or after ESPB. Both patients were highly satisfied with pain management technique.

DISCUSSION

ESPB is primarily an ultrasound-guided block, and as it is an easy, safe, and effective technique, it is being used to manage many painful conditions.[2,3,4] The mechanism of action is still debatable; however, it is speculated that if local anaesthetic is injected below the covering sheath of ESM and TP, local anaesthetic spreads cephalo-caudally and blocks the pain by action on dorsal rami, ventral rami, and lateral cutaneous branches of intercostal nerves.[5] Local anaesthetic spread has also been observed in paravertebral space.[6] The extent of block is volume-dependent as the local anaesthetic can spread from nuchal line to sacrum depending on the injection volume.[5,7]

The fractured ribs result in severe pain, and regional analgesic techniques are preferred choice for pain management.[8] The truncal blocks specially ESPB are very effective and safe ultrasound-guided techniques for pain management in such patients.[7,9] We used fluoroscopic guidance to identify the primary landmark that is the TP. Its recognition was easier than ultrasonography (USG) where TP can easily be confused with ribs and block efficacy may be compromised. During USG, the linear spread of local anaesthetic below the ESM in both the directions is taken as a sign of correct needle placement.[10] Under fluoroscopy, this was judged in similar manner because inappropriate needle position would not result in smooth linear spread of contrast. Moreover, both patients had effective analgesia as expected. The successful management of these two cases and ease of procedure suggest that fluoroscopic guidance can be used to give ESPB. Ultrasound is devoid of radiation hazards and has sufficient scientific literature support for success and safety regarding ESPB. Therefore, at this moment we cannot suggest that fluoroscopic guidance is an alternative to USG. However, this report suggests that it is feasible to give ESPB safely and effectively under fluoroscopic guidance.

CONCLUSION

It is feasible to give ESPB safely and effectively under fluoroscopic guidance.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forero M, Adhikary SD, Lopez H, Tsui C, Chin KJ. The erector spinae plane block: A novel analgesic technique in thoracic neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:621–7. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forero M, Rajarathinam M, Adhikary S, Chin KJ. Erector spinae plane (ESP) block in the management of post thoracotomy pain syndrome: A case series. Scand J Pain. 2017;17:325–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veiga M, Costa D, Brazão I. Erector spinae plane block for radical mastectomy: A new indication? Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2018;65:112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamak Altinpulluk E, García Simón D, Fajardo-Pérez M. Erector spinae plane block for analgesia after lower segment caesarean section: Case report. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2018;65:284–6. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivanusic J, Konishi Y, Barrington MJ. A cadaveric study investigating the mechanism of action of erector spinae blockade. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:567–71. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueshima H, Hiroshi O. Spread of local anesthetic solution in the erector spinae plane block. J Clin Anesth. 2018;45:23. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton DL, Manickam B. Erector spinae plane block for pain relief in rib fractures. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:474–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadon A. Pain management in multiple fractured ribs; role of regional analgesia. American J Anesth Clin Res. 2017;3:20–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nandhakumar A, Nair A, Bharath VK, Kalingarayar S, Ramaswamy BP, Dhatchinamoorthi D, et al. Erector spinae plane block may aid weaning from mechanical ventilation in patients with multiple rib fractures: Case report of two cases. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:139–41. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_599_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin KJ, Adhikary S, Forero M. Is the erector spinae plane (ESP) block a sheath block? A reply. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:916–7. doi: 10.1111/anae.13926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]