Abstract

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. In this study, we used a bioactivity-guided isolation technique to identify constituents of Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) with antiproliferative activity against human lung adenocarcinoma cells.

Methods

Bioactivity-guided fractionation and preparative/semipreparative HPLC purification were used with LC/MS analysis to separate the bioactive constituents. Cell viability and apoptosis in human lung cancer cell lines (A549, H1264, H1299, and Calu-6) after treatment with KRG extract fractions and constituents thereof were assessed using the water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-1) assay and terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining, respectively. Caspase activation was assessed by detecting its surrogate marker, cleaved poly adenosine diphosphate (ADP-ribose) polymerase, using an immunoblot assay. The expression and subcellular localization of apoptosis-inducing factor were assessed using immunoblotting and immunofluorescence, respectively.

Results and conclusion

Bioactivity-guided fractionation of the KRG extract revealed that its ethyl acetate–soluble fraction exerts significant cytotoxic activity against all human lung cancer cell lines tested by inducing apoptosis. Chemical investigation of the ethyl acetatesoluble fraction led to the isolation of six ginsenosides, including ginsenoside Rb1 (1), ginsenoside Rb2 (2), ginsenoside Rc (3), ginsenoside Rd (4), ginsenoside Rg1 (5), and ginsenoside Rg3 (6). Among the isolated ginsenosides, ginsenoside Rg3 exhibited the most cytotoxic activity against all human lung cancer cell lines examined, with IC50 values ranging from 161.1 μM to 264.6 μM. The cytotoxicity of ginsenoside Rg3 was found to be mediated by induction of apoptosis in a caspase-independent manner. These findings provide experimental evidence for a novel biological activity of ginsenoside Rg3 against human lung cancer cells.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cytotoxicity, Ginsenoside Rg3, Korean Red Ginseng, Lung cancer

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is not only the most commonly diagnosed cancer but also the leading cause of cancer-associated death worldwide [1]. Despite advances in early diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis of patients with lung cancer remains very poor, with a 5-year survival rate of around 16% [1]. Therefore, screening for, identifying, and validating bioactive compounds with anti–lung cancer potential is important for developing improved lung cancer treatments.

Panax ginseng Meyer (Araliaceae), also known as Korean ginseng, is a type of ginseng that has been used for various therapeutic purposes in traditional Korean medicine. P. ginseng is found in Korea, the northeastern region of China, and the eastern region of Siberia. In Korea, P. ginseng roots are treated with cycles of steaming and drying, which make the roots turn dark [2]. The final processed product is called Korean Red Ginseng (KRG), a heat-processed Korean ginseng. KRG extract is a well-known commercial product in Korea and is consumed to promote well-being and vitality. For the last few decades, extensive studies on KRG extract have demonstrated its potent pharmacological activities including anticancer, antiinflammatory, antioxidant, and antidiabetic effects [3], [4], [5], [6].

Ginseng contains a variety of ginsenosides with diverse biological activities. Although ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, and Rg1 are the main constituents in both dried (white) and steamed (red) ginseng, KRG has been reported to contain more less polar ginsenosides such as Rg3, Rg5, Rk1, and F4 [7]. These less polar ginsenosides have been shown to exhibit potent biological activities, including radical scavenging, vasodilating, and neuroprotective activities, as well as antiproliferative activity against cancer cells [8], [9], [10], [11].

The anticancer potential of KRG has been demonstrated in various types of human cancer, including prostate, liver, colon, and breast cancer, both in vitro and in vivo [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. In addition, long-term treatment with KRG extract and its less polar ginsenosides Rg3 and Rg5 was shown to reduce the incidence of benzo(a)pyrene–induced lung tumors in mice [17]. However, little is known regarding the mechanisms underlying the antitumor effects of KRG and its constituents. Although one study showed that a lipid-soluble KRG extract is cytotoxic to the human lung cancer cell line H460 in vitro [18], the specific chemical components responsible for its cytotoxic effect against lung cancer cells remain to be elucidated. In addition, because the genetic heterogeneity of cancer (e.g., the status of the tumor suppressor p53 gene) is correlated with chemo resistance in patients with cancer [19], [20], the antiproliferative effects of KRG and its constituents against human lung cancer need to be further validated in more human lung cancer cell lines.

In the present study, as part of our continuing efforts to discover compounds in Korean natural resources with antiproliferative activity against human lung cancer [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], we explored the antiproliferative effects of KRG against human lung cancer cells. Six ginsenosides (1–6) were isolated from the active fraction through bioactivity-guided fractionation based on their cytotoxic activity and subsequent chemical investigation. The isolated ginsenosides were then evaluated for their cytotoxicity against human lung cancer cell lines. Here, we present the cytotoxic effects of KRG on human lung cancer cells in vitro, identify the active compounds responsible for these effects, and determine the underlying mechanism of their actions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of KRG extract

KRG extracts were manufactured from the roots of fresh 6-year-old P. ginseng provided by the Korea Ginseng Corporation (Supplemental materials and methods).

2.2. Isolation of compounds using bioactivity-guided fractionation

KRG extract (10 g) was dissolved in distilled water and successively solvent partitioned with hexane (HX), dichloromethane [CH2Cl2 (MC)], ethyl acetate [EtOAC, (EA)], and n-butanol (n-BuOH) (each 700 mL × 3), thereby generating HX- (103 mg), MC- (325 mg), EA- (134 mg), and BuOH (246 mg)-miscible fractions, respectively. The resultant fractions were then dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as stock solutions at a concentration of 150 mg/mL and evaluated for their cytotoxic activity against human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines.

To identify the cytotoxic chemical constituents, the EA-soluble fraction (134 mg) was chosen for further investigation. The rationale behind this choice was that the EA-soluble fraction showed the highest cytotoxic activity against all human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines examined. The detailed process of the isolation of compounds from the EA-soluble fraction was described in Supplemental materials and methods.

2.3. Cell culture

All human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, the A549 cell line expressing wild-type p53, the H1264 cell line harboring mutant p53, the H1299 cell line, and the Calu-6 cell line null for p53 [26], [27], were grown in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) and antibiotics (WelGENE, Seoul, Korea) as previously described [21]. The origin of the cell lines was described in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

2.4. Cell viability analysis

5 × 103 cells per well were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and grown overnight. The cells were then incubated with various concentrations of KRG fractions or compounds isolated from the EA fraction. Cells were also treated with growth medium containing 0–1.0% DMSO as vehicle controls. At 48 h after treatment, the viability of human lung cancer cells was assessed using the WST-1 cell proliferation assay kit (Daeil Lab Service Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea) as previously described [24]. Data are presented as percentages of the corresponding vehicle control. The IC50 values of the KRG fractions and the isolated compounds were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose–response curve using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

2.5. TUNEL assay

7.5 × 103 cells were seeded on 12-mm glass coverslips and grown overnight. The cells were then treated with 400 μg/mL of each KRG fraction or 250 μM of ginsenoside Rg3 isolated from the EA fraction. Cells were also incubated with growth medium containing 0.27% or 0.5% DMSO as vehicle controls. After 48 h of treatment, apoptotic cells were assessed by TUNEL staining using the DeadEnd labeling kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions and examined under a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) as previously described [24]. The percentage of apoptotic cells was defined as the number of cells positive for TUNEL staining divided by the total number of cells counted in six randomly selected high-power fields (400×) on each slide.

2.6. Immunoblotting

5 × 105 H1264 and Calu-6 cells were plated in 60-mm tissue culture dishes (Thermo Scientific), grown overnight, and treated with growth medium containing 250 μM of ginsenoside Rg3 (isolated from the EA fraction) or 0.5% DMSO as a vehicle control. Cells were also treated with 1 μM doxorubicin (Sigma-Aldrich) as a positive control. At 18 or 48 h after treatment, cells were harvested and lysed with Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with 1 μM DTT, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Sigma-Aldrich), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Proteins in the resultant whole cell lysates were then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and probed for apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), and β-Actin as a loading control using anti-AIF, anti-PARP (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and anti-β-Actin (Thermo Scientific) antibodies, respectively.

Relative gel densities were determined by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and normalization to β-actin as previously described [28].

2.7. Immunofluorescence

7.5 × 103 H1264 and Calu-6 cells were seeded on 12-mm glass coverslips, grown overnight, and incubated with 250 μM of ginsenoside Rg3 (isolated from the EA fraction) or 0.5% DMSO as a vehicle control. At 18 h after treatment, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS (PBST) for 15 min, and blocked with 10% normal goat serum (NGS, Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) in PBST for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with anti-AIF antibodies diluted 1:50 in 2% NGS in PBST overnight at 4°C, further incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) diluted 1:1000 in 2% NGS in PBST for 2 h at room temperature, and counterstained with 1 μg/mL Hoechst dye to visualize cell nuclei. The percentage of cells with nuclear AIF was defined as the number of cells positive for nuclear AIF staining divided by the total number of cells counted in six randomly selected high-power fields (630×) on each slide.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The Student two-tailed unpaired t test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences between cells treated with KRG fractions or the isolated compounds versus cells treated with vehicle controls. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEMs), and p values less than 0.05 were statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

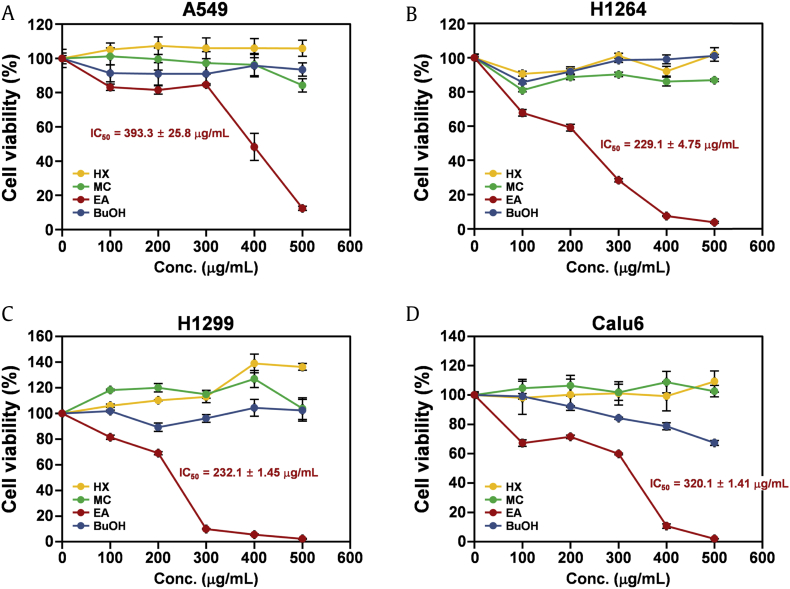

To examine the biological activities of KRG in human lung cancer cells, the KRG extract was fractionated into four fractions: HX-soluble, MC-soluble, EA-soluble, and BuOH-soluble. Because the tumor suppressor p53 has been shown to confer chemo resistance in many types of human cancer [19], [20], the effects of each fraction on human lung cancer cells were investigated in four human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, A549, H1264, H1299, and Calu-6, with different p53 statuses (Fig. 1). Assessment of viable cells using the WST-1 assay after 48 h of treatment revealed that, among the four KRG fractions, the EA-soluble fraction significantly reduced cell viability in all human lung cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50 values ranging from 229.1 μg/mL to 393.3 μg/mL (Fig. 1A–1D). These observations suggest that KRG has cytotoxic potential against human lung cancer cells and that its EA fraction contains constituent(s) mediating its cytotoxic effects. In addition, these data also imply that cellular p53 status does not affect the cytotoxic activity of KRG toward human lung cancer cells.

Fig. 1.

The EA fraction of KRG extract significantly decreases the viability of human lung adenocarcinoma cells. (A) Effects of the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract on the viability of A549 cells. (B) Effects of the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract on the viability of H1264. (C) Effects of the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract on the viability of H1299. (D) Effects of the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract on the viability of Calu-6 cells. Cells were treated with the fractions at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. The viability of cells was then assessed by WST-1 assay. Data are presented as means ± SEMs.

BuOH, n-butanol; EA, ethyl acetate; HX, hexane, MC, dichloromethane; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng.

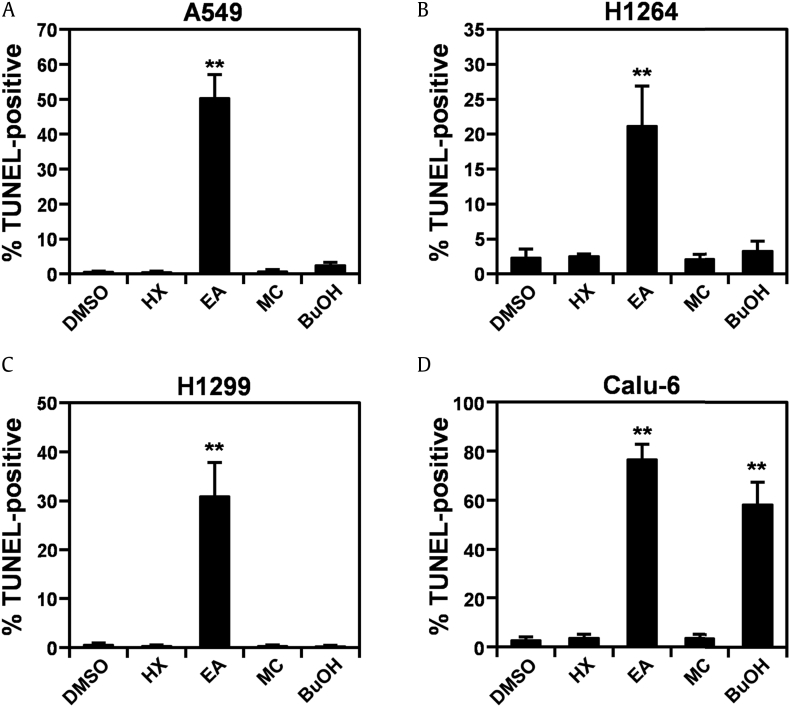

Red ginseng has been demonstrated to induce apoptotic cell death in various types of human cancer cells, including colon and breast cancer cells [29], [30]. Therefore, it is possible that the cytotoxicity of KRG to human lung cancer cells is mediated by apoptosis. Indeed, on treatment with the EA fraction of KRG, human lung cancer cells showed typical morphological features of apoptotic cells, such as rounding and shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and detachment from the substratum [31] (Supplemental Fig. 1). To further verify that KRG increases apoptosis in human lung cancer cells, we quantified the percentage of apoptotic cells using TUNEL staining in human lung cancer cell lines treated with each KRG fraction (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 2). At 48 h after treatment, neither the HX nor MC fraction had induced apoptosis in any human lung cancer cell line examined (Fig. 2A–2D). Although the BuOH fraction increased the percentage of apoptotic Calu-6 cells (Fig. 2D and Supplemental Fig. 2D), it did not induce apoptosis in any other lung cancer cell line (Fig. 2A–2C). However, in parallel with the cell viability data shown in Fig. 1, the EA fraction dramatically increased the apoptotic cell population compared with the vehicle control in all human lung cancer cell lines (Fig. 2A–2D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the EA fraction of KRG decreased the viability in human lung cancer cells by inducing apoptosis and further supports that the constituents of the EA fraction mediated the cytotoxic activity of KRG against human lung cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

The EA fraction of KRG extract induces apoptotic cell death in human lung adenocarcinoma cells.(A) Quantitation of apoptotic cells in A549 cells treated with the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract. (B) Quantitation of apoptotic cells in H1264 cells treated with the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract. (C) Quantitation of apoptotic cells in H1299 cells treated with the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract. (D) Quantitation of apoptotic cells in Calu-6 cells treated with the HX, MC, EA, and BuOH fractions of KRG extract. Cells were treated with the fractions or DMSO as a vehicle control for 48 h. Apoptotic cells were then detected by TUNEL staining. Data are presented as means ± SEMs. **p < 0.01.

BuOH, n-butanol; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EA, ethyl acetate; HX, hexane, MC, dichloromethane; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng.

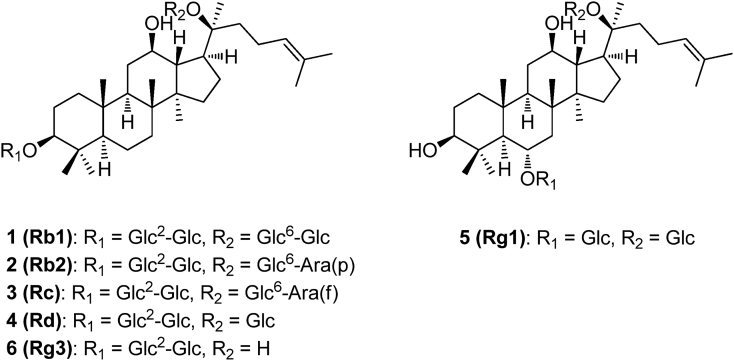

Therefore, we then investigated the EA fraction to identify which constituents in this fraction contributed to the cytotoxicity of KRG against human lung cancer cells in vitro. Chemical investigation of the EA fraction using semipreparative HPLC purification together with LC/MS analysis led to the isolation of ginsenoside Rb1 (1) [32], ginsenoside Rb2 (2) [33], ginsenoside Rc (3) [33], ginsenoside Rd (4) [34], ginsenoside Rg1 (5) [35], and ginsenoside Rg3 (6) [36] (Fig. 3). These ginsenosides were identified by the guidance of NMR spectra, LC/MS data, and comparison with previously reported data.

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of the compounds 1–6.

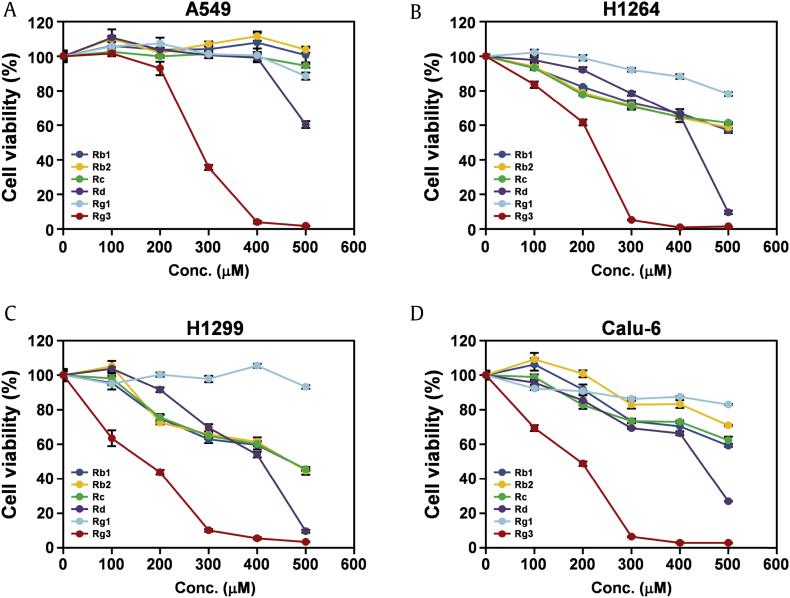

All six isolated ginsenosides were then evaluated for their cytotoxic effects against human lung cancer cells (Fig. 4). Among the isolated ginsenosides, ginsenoside Rg3 exhibited the most potent cytotoxicity to all human lung cancer cell lines tested, with IC50 values ranging from 161.1 μM to 264.6 μM (Fig. 4A–4D and Table 1). Moreover, the cytotoxic effects of ginsenoside Rg3 were dose dependent. In addition, the cytotoxic effect of ginsenoside Rg3 against human lung cancer cells was not correlated with the cellular p53 status. These findings strongly suggest that ginsenoside Rg3 is the main constituent responsible for the cytotoxic effect of KRG against human lung cancer cells in vitro.

Fig. 4.

Ginsenoside Rg3 isolated from the EA fraction of KRG reduces the viability of human lung cancer cells. (A–D) Cell viability was assessed by the WST-1 assay in four human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, (A) A549, (B) H1264, (C) H1299, and (D) Calu-6, after treatment with ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Rg1, and Rg3 isolated from the EA fraction of KRG for 48 h. Data are presented as means ± SEMs.

EA, ethyl acetate; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng.

Table 1.

IC50 values (μM) for the six ginsenosides isolated from the EA fraction of KRG against human lung cancer cell lines

| Cell lines | Compounds |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rb1 | Rb2 | Rc | Rd | Rg1 | Rg3 | |

| A549 | ND1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 264.6 ± 4.52 |

| H1264 | ND | ND | ND | 466.5 ± 8.3 | ND | 235.2 ± 4.5 |

| H1299 | 455.4 ± 10.2 | 454.3 ± 19.5 | 461.9 ± 10.9 | 404.5 ± 8.2 | ND | 161.1 ± 9.9 |

| Calu-6 | ND | ND | ND | 447.8 ± 1.4 | ND | 182.5 ± 6.3 |

ND, not determined.

Values are the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations.

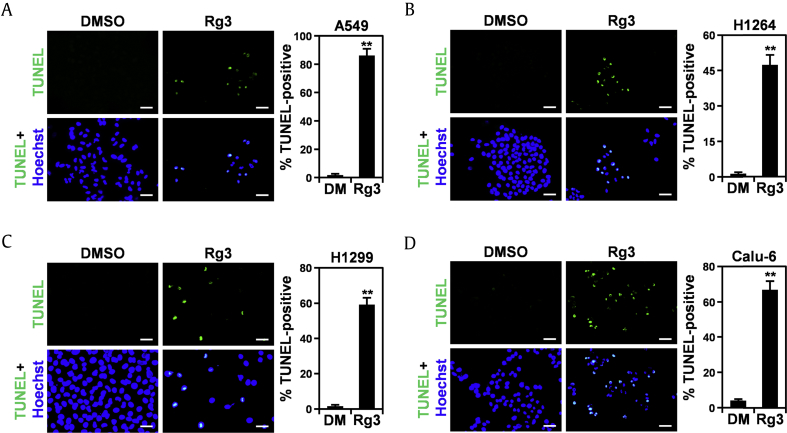

Ginsenoside Rg3 has been shown to induce apoptosis in various types of human cancer cells, including glioblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colon cancer cells [37], [38], [39]. Consistent with these findings, on ginsenoside Rg3 treatment, human lung cancer cells underwent morphological changes similar to those treated with the EA fraction of KRG (Supplemental Fig. 3), implying that ginsenoside Rg3 reduces the viability of human lung cancer cells by inducing apoptosis. To further confirm the proapoptotic activity of ginsenoside Rg3 against human lung cancer cell lines, lung cancer cells were treated with ginsenoside Rg3 and then apoptotic cell death was measured using TUNEL staining (Fig. 5). As expected, treatment with ginsenoside Rg3 for 48 h significantly increased the apoptotic subpopulations of all human lung cancer cell lines tested compared with DMSO-treated control cells. These observations suggest that the cytotoxic effect of ginsenoside Rg3 against human lung cancer cells is mediated by its proapoptotic activity and further support that the cytotoxicity of KRG to human lung cancer cells can be attributed to ginsenoside Rg3.

Fig. 5.

Ginsenoside Rg3 increases the subpopulation of human lung adenocarcinoma cells undergoing apoptosis. (A) Representative images of TUNEL staining (left) and quantitation of TUNEL-positive cells (right) in A549 cells treated with KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 or 0.5% DMSO (DM) as a vehicle control for 48 h. (B) Representative images of TUNEL staining (left) and quantitation of TUNEL-positive cells (right) in H1264 cells treated with KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 or 0.5% DMSO (DM) as a vehicle control for 48 h. (C) Representative images of TUNEL staining (left) and quantitation of TUNEL-positive cells (right) in H1299 cells treated with KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 or 0.5% DMSO (DM) as a vehicle control for 48 h. (D) Representative images of TUNEL staining (left) and quantitation of TUNEL-positive cells (right) in Calu-6 cells treated with KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 or 0.5% DMSO (DM) as a vehicle control for 48 h. Data are presented as means ± SEMs. Scale bar: 50 μM. **p < 0.01.

DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng.

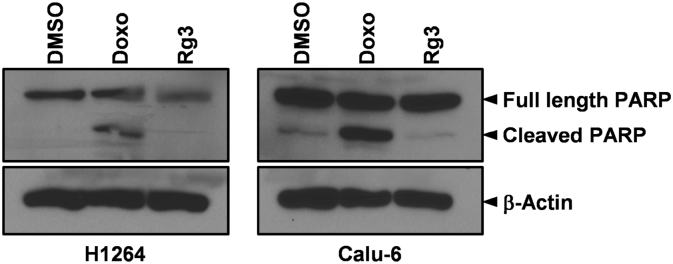

In various types of human cancer cells including glioblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, colon cancer, and gallbladder, ginsenoside Rg3 has been shown to induce apoptosis in a caspase-dependent manner [37], [38], [39], [40]. However, a recently published study demonstrated that ginsenoside Rg3 also triggers apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma and colon cancer cells in a caspase-independent manner [41]. Furthermore, in neuroblastoma cells, ginsenoside Rg3 blocks apoptosis by attenuating caspase-3 activation [42]. Hence, it is likely that ginsenoside Rg3 induces apoptosis in human cancer cells in caspase-dependent and/or caspase-independent ways, depending on the specific cellular context and experimental conditions. To explore the mechanisms underlying apoptosis induced by KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 in human lung cancer cells, we assessed cleavage of PARP, a surrogate marker of caspase activation [43], in H1264 and Calu-6 cells treated with ginsenoside Rg3 (Fig. 6). After 48 h, the well-known anticancer agent doxorubicin (which induces apoptosis via caspase activation) dramatically increased the levels of the cleaved form of PARP in both H1264 and Calu-6 cells, compared with the level in vehicle control-treated cells [44]. However, ginsenoside Rg3 treatment failed to significantly induce PARP cleavage compared with the vehicle control in these lung cancer cell lines. These observations suggest that KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 induces apoptosis in the lung cancer cell lines examined through a caspase-independent pathway.

Fig. 6.

KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 does not induce PARP cleavage in H1264 or Calu-6 human lung cancer cells. H1264 and Calu-6 cells were incubated with 250 μM of KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 for 48 h. Cells were also treated with 0.5% DMSO and 1 μM doxorubicin (Doxo) as a negative and positive control, respectively. Whole cell lysates were then prepared and probed for PARP and β-actin as a loading control. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase.

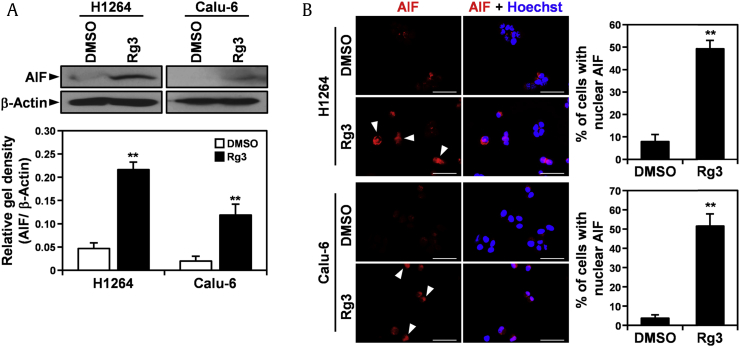

Nuclear translocation and upregulation of AIF, a flavoprotein normally residing in the mitochondrial intermembrane, elicits chromatin condensation and fragmentation, leading to apoptosis without evidence of caspase activation [45], [46]. Therefore, to further verify that KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 induces apoptosis in human lung cancer cells through a caspase-independent apoptotic pathway, we examined the effect of ginsenoside Rg3 on the expression and subcellular localization of AIF in H1264 and Calu-6 cells (Fig. 7). Of note, ginsenoside Rg3 treatment for 18 h significantly increased the expression of AIF in both lung cancer cell lines (Fig. 7A). In addition, detection of AIF using immunofluorescence staining revealed that ginsenoside Rg3 induced nuclear accumulation of AIF in these cell lines (Fig. 7B). These observations indicate that ginsenoside Rg3 induced apoptosis in the human lung cancer cell lines tested by inducing AIF expression and by stimulating nuclear translocation of AIF. They also support the hypothesis that ginsenoside Rg3 is cytotoxic to human lung cancer cells by inducing apoptosis in a caspase-independent manner.

Fig. 7.

Treatment with KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 increases AIF expression and triggers AIF nuclear localization in H1264 and Calu-6 cells. (A) H1264 and Calu-6 cells were incubated with 250 μM KRG-derived Rg3 or 0.5% DMSO as a vehicle control for 18 h. Whole cell lysates were then prepared and probed for AIF and β-actin as a loading control. (B) Representative images are shown of H1264 and Calu-6 cells stained for AIF (left) and quantitation of cells with nuclear AIF (right) after treatment with 250 μM KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 or 0.5% DMSO as a vehicle control for 18 h. Arrowheads indicate cells with nuclear translocation of AIF. Data are presented as means ± SEMs. Scale bar: 50 μM. **p < 0.01.

AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; KRG, Korean Red Ginseng.

Long-term administration of the KRG extract or of KRG-derived ginsenoside Rg3 has been shown to significantly reduce lung tumor incidence mediated by benzo(a)pyrene in mice [17]. However, the mechanisms underlying the antitumor activities of KRG and its constituents (e.g., ginsenoside Rg3) against lung cancer remain to be fully elucidated. In this study, we found that KRG extract, its EA fraction, exerted antiproliferative effects against four different human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, A549, H1264, H1299, and Calu-6. These effects were irrespective of cellular p53 status and were mediated by induction of apoptotic cell death. In addition, we demonstrated that the cytotoxic effects of KRG against human lung cancer cells can be attributed to the cytotoxic and proapoptotic activities of ginsenoside Rg3. Together with a previous study showing the in vitro cytotoxicity of the lipid-soluble KRG fraction against the H460 human lung cancer cell line [18], our findings provide a partial explanation for the molecular basis of the antitumor potential of KRG against lung cancer previously observed in vivo [17]. They also support the potential use of KRG as a functional food for the prevention and treatment of human lung cancer.

Ginsenoside Rg3 has been demonstrated to have various pharmacological activities with anticancer properties, such as angiostatic and immunomodulatory activities as well as antiproliferative activity against cancer cells [47]. In particular, the cytotoxic effects of ginsenoside Rg3 have been evaluated in a broad spectrum of cancer types in both in vitro and in vivo models [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [47], supporting its potential use for therapeutic intervention in cancer. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying its cytotoxicity against cancer cells are still under debate. Most studies have shown that ginsenoside Rg3 is cytotoxic to various types of human cancer cells, including glioblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, colon cancer, and gallbladder cancer, by inducing caspase-dependent apoptosis [37], [38], [39], [40], [48]. However, a recently published study demonstrated that in hepatocellular carcinoma and colon cancer cells, apoptosis triggered by ginsenoside Rg3 treatment is partially but not significantly attenuated by pharmacological inhibition of caspases [41], suggesting that the proapoptotic activity of ginsenoside Rg3 is also mediated by caspase-independent apoptotic pathways. Indeed, in this study, we observed that ginsenoside Rg3 induced apoptosis in human lung cancer cells in a caspase-independent manner. In addition, we demonstrated for the first time that ginsenoside Rg3 affected the expression and subcellular localization of AIF, which are key events in the caspase-independent intrinsic apoptotic pathway [45], [46], in human lung cancer cells.

Considering our findings and previous studies, we hypothesize that ginsenoside Rg3 induces apoptosis in human cancer cells by triggering caspase-dependent and/or caspase-independent pathways, depending on the particular cellular context and experimental conditions. Similar to ginsenoside Rg3, ginsenoside compound K and ginsenoside Rh2 have also been shown to exhibit cytotoxic activities against human cancer cells by activating caspase-mediated and AIF-mediated cell death [49], [50], [51], [52]. These findings further support our hypothesis that both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways mediate the proapoptotic activity of ginsenoside Rg3 in human cancer cells. Taken together, our findings broaden the potential application of KRG and its ginsenoside Rg3 for treating human lung cancer, especially non–small cell lung carcinoma resistant to induction of apoptosis by conventional cancer therapies, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy [53], [54].

In conclusion, here we demonstrated that KRG was cytotoxic to human lung cancer cells in vitro and that this effect was mediated by the induction of apoptosis. In addition, we identified ginsenoside Rg3 as the main active constituent contributing to the cytotoxicity of KRG to human lung cancer cells. Furthermore, we found that ginsenoside Rg3 upregulated AIF expression and stimulated nuclear translocation of AIF in human lung cancer cells, leading to caspase-independent apoptotic cell death. Our findings reveal the potential of KRG as a functional food for lung cancer prevention and treatment as well as its underlying mechanism of action.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2015R1C1A1A02037383) and by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2012R1A5A2A28671860).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2018.02.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Jemal A., Siegel R., Xu J., Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeg I.H., So S.H. The world ginseng market and the ginseng (Korea) J Ginseng Res. 2013;37:1–7. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim P., Park J.H., Kwon K.J., Kim K.C., Kim H.J., Lee J.M., Kim H.Y., Han S.H., Shin C.Y. Effects of Korean red ginseng extracts on neural tube defects and impairment of social interaction induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;51:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park H.M., Kim S.J., Mun A.R., Go H.K., Kim G.B., Kim S.Z., Jang S.I., Lee S.J., Kim J.S., Kang H.S. Korean red ginseng and its primary ginsenosides inhibit ethanol-induced oxidative injury by suppression of the MAPK pathway in TIB-73 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;141:1071–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul S., Shin H.S., Kang S.C. Inhibition of inflammations and macrophage activation by ginsenoside-Re isolated from Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1354–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H., Choi J., Shin S.S., Yoon M. Effects of Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng) on obesity and adipose inflammation in ovariectomized mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;178:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim D.H. Chemical diversity of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquifolium, and Panax notoginseng. J Ginseng Res. 2012;36(1):1–15. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim W.Y., Kim J.M., Han S.B., Lee S.K., Kim N.D., Park M.K., Kim C.K., Park J.H. Steaming of ginseng at high temperature enhances biological activity. J Nat Prod. 2000;63(12):1702–1704. doi: 10.1021/np990152b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim N.D., Kim E.M., Kang K.W., Cho M.K., Choi S.Y., Kim S.G. Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits phenylephrine-induced vascular contraction through induction of nitric oxide synthase. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140(4):661–670. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian J., Fu F., Geng M., Jiang Y., Yang J., Jiang W., Wang C., Liu K. Neuroprotective effect of 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg3 on cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;374(2):92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C.Z., Anderson S., DU W., He T.C., Yuan C.S. Red ginseng and cancer treatment. Chin J Nat Med. 2016;14(1):7–16. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1009.2016.00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae J.K., Kim Y.J., Chae H.S., Kim D.Y., Choi H.S., Chin Y.W., Choi Y.H. Korean red ginseng extract enhances paclitaxel distribution to mammary tumors and its oral bioavailability by P-glycoprotein inhibition. Xenobiotica. 2016;17:1–10. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2016.1182233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S., Park J.M., Jeong M., Han Y.M., Go E.J., Ko W.J., Cho J.Y., Kwon C.I., Hahm K.B. Korean red ginseng ameliorated experimental pancreatitis through the inhibition of hydrogen sulfide in mice. Pancreatology. 2016;16:326–336. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung S.Y., Kim C., Kim W.S., Lee S.G., Lee J.H., Shim B.S., Kim S.H., Ahn K.S. Korean red ginseng extract enhances the anticancer effects of Imatinib mesylate through abrogation p38 and STAT5 activation in KBM-5 cells. Phytother Res. 2015;29:1062–1072. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H., Hong M.K., Choi H., Moon H.S., Lee H.J. Chemopreventive effects of Korean red ginseng extract on rat hepatocarcinogenesis. J Cancer. 2015;6:1–8. doi: 10.7150/jca.10353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin X., Che D.B., Zhang Z.H., Yan H.M., Jia Z.Y., Jia X.B. Ginseng consumption and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. J Ginseng Res. 2016;40:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yun T.K., Lee Y.S., Lee Y.H., Kim S.I., Yun H.Y. Anticarcinogenic effect of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer and identification of active compounds. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16(Suppl):S6–S18. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.S.S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang M.R., Kim H.M., Kang J.S., Lee K., Lee S.D., Hyun D.H., In M.J., Park S.K., Kim D.C. Lipid-soluble ginseng extract induces apoptosis and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in NCI-H460 human lung cancer cells. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2011;66(2):101–106. doi: 10.1007/s11130-011-0232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbst R.S., Heymach J.V., Lippman S.M. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1367–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z., Sun Y. Targeting p53 for novel Anticancer Therapy. Transl Oncol. 2010;3(1):1–12. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee T.K., Roh H.S., Yu J.S., Baek J., Lee S., Ra M., Kim S.Y., Baek K.H., Kim K.H. Pinecone of Pinus koraiensis inducing apoptosis in human lung cancer cells by activating caspase-3 and its chemical constituents. Chem Biodivers. 2017;14(4):e1600412. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201600412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J.S., Roh H.S., Lee S., Jung K., Baek K.H., Kim K.H. Antiproliferative effect of Momordica cochinchinensis seeds on human lung cancer cells and isolation of the major constituents. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2017;27(3):329–333. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baek J., Roh H.S., Choi C.I., Baek K.H., Kim K.H. Raphanus sativus sprout causes selective cytotoxic effect on p53-deficient human lung cancer cells in vitro. Nat Prod Commun. 2017;12(2):237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee T.K., Roh H.S., Yu J.S., Kwon D.J., Kim S.Y., Baek K.H., Kim K.H. A novel cytotoxic activity of the fruit of Sorbus commixta against human lung cancer cells and isolation of the major constituents. J Funct Foods. 2017;30:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S., So H.M., Roh H.S., Kim J., Yu J.S., Lee S., Seok S., Pang C., Baek K.H., Kim K.H. Vulpinic acid contributes to the cytotoxicity of Pulveroboletus ravenelii to human cancer cells by inducing apoptosis. RSC Adv. 2017;7:35297–35304. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitsudomi T., Steinberg S.M., Nau M.M., Carbone D., Damico D., Bodner S., Oie H.K., Linnoila R.I., Mulshine J.L., Minna J.D. p53 gene mutations in non-small-cell-lung-cancer cell-lines and their correlation with the presence of ras mutations and clinical features. Oncogene. 1992;7(1):171–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rämet M., Castrén K., Järvinen K., Pekkala K., Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T., Soini Y., Pääkkö P., Vähäkangas K. p53 protein expression is correlated with benzo[a]pyrene-DNA adducts in carcinoma cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16(9):2117–2124. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.9.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heidebrecht F., Heidebrecht A., Schulz I., Behrens S.E., Bader A. Improved semiquantitative Western blot technique with increased quantification range. J Immunol Methods. 2009;345(1–2):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C.Z., Li X.L., Wang Q.F., Mehendale S.R., Fishbein A.B., Han A.H., Sun S., Yuan C.S. The mitochondrial pathway is involved in American ginseng-induced apoptosis of SW- 480 colon cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:577–584. doi: 10.3892/or_00000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J.I., Ha Y.W., Choi T.W., Kim H.J., Kim S.M., Jang H.J., Choi J.H., Choi M.H., Chung B.C., Sethi G. Cellular uptake of ginsenosides in Korean white ginseng and red ginseng and their apoptotic activities in human breast cancer cells. Planta Med. 2011;77(2):133–140. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(4):495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gebhardt S., Bihler S., Schubert-Zsilavecz M., Riva S., Monti D., Falcone L., Daniele B. Biocatalytic generation of molecular diversity: modification of ginsenoside Rb1 by β-1,4-galactosyltransferase and Candida Antarctica lipase, part 4. Helvetica. 2002;85:1943–1959. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su J., Li H.Z., Yang C.R. Studies on saponin constituents in roots of Panax quinquefolium. Zhangguo Zhang Yao Za Zhi. 2003;9:830–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teng R., Ang C., McManus D., Armstrong D., Mau S., Bacic An. Regioselective acylation of ginsenosides by novozyme 435 to generate molecular diversity. Helvetica. 2004;87:1860–1872. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ko S.R., Choi K.J., Suzki K., Suzuki Y. Enzymatic preparation of ginsenosides Rg2, Rh1, and F1. Chem Pharm Bull. 2003;51:404–408. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W., Zhao Y., Rayburn E.R., Hill D.L., Wang H., Zhang R. In vitro anti-cancer activity and structure–activity relationships of natural products isolated from fruits of Panax ginseng. Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 2007;59:589–601. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S.Y., Kim G.T., Roh S.H., Song J.S., Kim H.J., Hong S.S., Kwon S.W., Park J.H. Proteomic analysis of the anti-cancer effect of 20S-ginsenoside Rg3 in human colon cancer cell lines. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73(4):811–816. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang J.W., Chen X.M., Chen X.H., Zheng S.S. Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma growth via intrinsic apoptotic pathway. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(31):3605–3613. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i31.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi Y.J., Lee H.J., Kang D.W., Han I.H., Choi B.K., Cho W.H. Ginsenoside Rg3 induces apoptosis in the U87MG human glioblastoma cell line through the MEK signaling pathway and reactive oxygen species. Oncol Rep. 2013;30(3):1362–1370. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F., Li M., Wu X., Hu Y., Cao Y., Wang X., Xiang S., Li H., Jiang L., Tan Z. 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg3 promotes senescence and apoptosis in gallbladder cancer cells via the p53 pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3969–3987. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S84527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D.G., Jung K.H., Lee D.G., Yoon J.H., Choi K.S., Kwon S.W., Shen H.M., Morgan M.J., Hong S.S., Kim Y.S. 20(S)-Ginsenoside Rg3 is a novel inhibitor of autophagy and sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to doxorubicin. Oncotarget. 2014;5(12):4438–4451. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He B., Chen P., Xie Y., Li S., Zhang X., Yang R., Wang G., Shen Z., Wang H. 20(R)-Ginsenoside Rg3 protects SH-SY5Y cells against apoptosis induced by oxygen and glucose deprivation/reperfusion. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017 Aug 15;27(16):3867–3871. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufmann S.H., Desnoyers S., Ottaviano Y., Davidson N.E., Poirier G.G. Specific proteolytic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: an early marker of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1993;53(17):3976–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gamen S., Anel A., Pérez-Galán P., Lasierra P., Johnson D., Piñeiro A., Naval J. Doxorubicin treatment activates a Z-VAD-sensitive caspase, which causes deltapsim loss, caspase-9 activity, and apoptosis in Jurkat cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258(1):223–235. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sevrioukova I.F. Apoptosis-inducing factor: structure, function, and redox regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14(12):2545–2579. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cregan S.P., Fortin A., MacLaurin J.G., Callaghan S.M., Cecconi F., Yu S.W., Dawson T.M., Dawson V.L., Park D.S., Kroemer G. Apoptosis-inducing factor is involved in the regulation of caspase-independent neuronal cell death. J Cell Biol. 2002;158(3):507–517. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun M., Ye Y., Xiao L., Duan X., Zhang Y., Zhang H. Anticancer effects of ginsenoside Rg3 (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2017;39(3):507–518. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim B.M., Kim D.H., Park J.H., Na H.K., Surh Y.J. Ginsenoside Rg3 induces apoptosis of human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cells. J Cancer Prev. 2013;18(2):177–185. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2013.18.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho S.H., Chung K.S., Choi J.H., Kim D.H., Lee K.T. Compound K, a metabolite of ginseng saponin, induces apoptosis via caspase-8-dependent pathway in HL-60 human leukemia cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:449. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Law C.K.M., Kwok H.H., Poon P.Y., Lau C.C., Jiang Z.H., Tai W.C.S., Hsiao W.W.L., Mak N.K., Yue P.Y.K., Wong R.N.S. Ginsenoside compound K induces apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via activation of apoptosis-inducing factor. Chin Med. 2014;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park J.A., Lee K.Y., Oh Y.J., Kim K.W., Lee S.K. Activation of caspase-3 protease via a Bcl-2-insensitive pathway during the process of ginsenoside Rh2-induced apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 1997;121(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00333-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qu X., Qu S., Yu X., Xu H., Chen Y., Ma X., Sui D. pseudo-G-Rh2 induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in SGC-7901 human gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;26(6):1441–1446. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joseph B., Ekedahl J., Lewensohn R., Marchetti P., Formstecher P., Zhivotovsky B. Defective caspase-3 relocalization in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Oncogene. 2001;20(23):2877–2888. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim M.Y. Role of GALNT14 in lung metastasis of breast cancer. BMB Rep. 2017;50(5):233–234. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.5.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.