Abstract

Perfluorinated alkylate substances (PFASs) are widely used and have resulted in human exposures worldwide. PFASs occur in breast milk, and the duration of breastfeeding is associated with serum-PFAS concentrations in children. To determine the time-dependent impact of this exposure pathway, we examined the serum concentrations of five major PFASs in a Faroese birth cohort at birth, and at ages 11, 18, and 60 months. Information about the children’s breastfeeding history was obtained from the mothers. The trajectory of serum-PFAS concentrations during months with and without breastfeeding was examined by linear mixed models that accounted for the correlations of the PFAS measurements for each child. The models were adjusted for confounders such as body size. The duration of exclusive breastfeeding was associated with increases of most PFAS concentrations by up to 30% per month, with lower increases during partial breast-feeding. In contrast to this main pattern, perfluorohexane sulfonate was not affected by breast-feeding. After cessation of breastfeeding, all serum concentrations decreased. This finding supports the evidence of breastfeeding being an important exposure pathway to some PFASs in infants.

INTRODUCTION

Perfluorinated alkylates (PFASs) are widely used to make industrial products resistant to water, oil or stains1. PFASs can have immunotoxic effects, and a major concern is that PFAS exposure may undermine childhood immunization programs2. Due to the particular vulnerability of the immune system during early development3, the sources of PFAS exposure in infants are of special interest. Concentrations of PFOS and PFOA in breast milk are generally between 20 and 100 ng/L4, and a daily milk intake of about 125 mL/kg body weight5 could easily contribute about 6 ng/kg per day or a total of 1 μg/kg for the recommended 6 months of breast-feeding6. These amounts may appear small, but elimination of long-chain PFASs in humans is very slow, with half-lives in adults thought to be several years7–9. PFAS concentrations in infant formulas are low4, 10, and exposure via human milk could therefore lead to elevated serum concentrations in breastfed infants11, 12. As a result, serum PFAS concentrations in the infant may eventually exceed those of the mother11, 13.

Breastfeeding is recommended by WHO as the exclusive food source for infants during the first 6 months after birth and onwards partially with supplementary food up to age 2 years14. This recommendation focuses on the beneficial effects for both mother and child. Although WHO did not consider the possible impact of environmental chemicals present in human milk, the risks and benefits of breast-feeding has sometimes been referred to as “the weanling’s dilemma”15.

The present study examines the association between months with exclusive or partial breastfeeding and serum- PFAS concentrations in the children up to age 5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects.

A birth cohort of 656 children born in the Faroe Islands was formed during 1997–2000 and followed prospectively.2 A serum sample and informed consent were obtained at week 32 of pregnancy. Only singleton births were included in the cohort. During a 12-month period of the follow-up period, a subgroup of mothers was invited to bring in their children for an examination and blood tests at ages 11 months and 18 months, while all children were invited for the examination at age 5 years. The prenatal exposure was assessed from the mother’s serum-PFAS concentrations at pregnancy week 32. Sufficient serum volume for chemical analysis at ages 11 or 18 months was available for 81 children and for 538 children at age 60 months.

The duration (in months) of exclusive and partial breastfeeding was obtained from the mothers, who filled in a questionnaire when the children were 5 years old. Our previous studies in this population have shown an excellent association between maternal reports on breastfeeding duration up to seven years later16. As traditional intake of pilot whale meat is a major source of PFAS exposure17, the mothers were asked whether or not the child had eaten any whale meals by age 5.

From the clinical examinations, the child’s birth weight and length as well as height and weight at subsequent follow-up were obtained to allow calculation of the ponderal index (PI; g/cm3). The ponderal index was chosen as an appropriate alternative to the body mass index to obtain a standardized measure of distribution volume during the infancy-childhood follow-up period.

Exposure assessment.

Major PFASs in serum collected at the clinical examinations were measured by online solid-phase extraction and followed by high-pressure liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry2, 18: perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorononanoate (PFNA), and perfluorodecanoate (PFDA). Quality control samples obtained from the German Quality Assurance Programme (Q-EQUAS) are included in each sample series analyzed. Within-batch imprecision (assessed by the coefficient of variation) was better than 3% and between-batch imprecision better than 5.6% for all analytes. The children’s neonatal serum-PFAS concentrations was calculated based on PFAS ratios between cord and maternal pregnancy serum concentrations previously estimated for the same cohort19: 0.74 (PFHxS); 0.34 (PFOA); 0.72 (PFOS); 0.50 (PFNA); and 0.29 (PFDA).

Statistical methods.

All PFAS concentrations were log-transformed prior to the analyses to obtain normally distributed residuals of the models. The age dependence of the PFAS concentration was modeled using a piece-wise linear model:

| (1) |

where is the log-transformed serum concentration of child at age , while , and indicates the number of months that the child was exclusively breastfed, partially breastfed, and not breastfed at all by age . At birth, the serum concentration is given by the intercept () which is allowed to be specific for each child. During the period of exclusive breastfeeding, the log-transformed concentration is assumed to change by a slope of per month. Likewise, during partial breastfeeding the slope is , and after weaning, the slope is .

We first included only the three concentrations obtained at birth and at age 11 and 18 months. The model was estimated using a linear mixed model with breastfeeding variables included as covariates. Heterogeneity between children in the PFAS levels at birth was modeled by assuming that the intercept followed a normal distribution with a mean and a variance . In this way we allow for correlation between PFAS measurements from the same child. The error terms were assumed to follow normal distributions with mean zero and an exponential serial covariance structure (cov( = σ2 exp(-d(a,a’) /ρ), where is the distance between age and age ). This addition allows serum concentrations at ages close in time to be more strongly correlated than measurements further apart.

We then extended the model to include the PFAS concentration at age 5 years and assessed the changes in serum concentrations during the period after weaning. The first model included the breastfeeding variables as described in Equation (1)

Then the analyses were repeated after adjustment for effects of sex, child size and exposure from whale meat intake at 60 months. The effect of the child’s size on the serum measured concentration was modeled by including child’s PI as an additional covariate so that the serum-PFAS concentration at a given age was assumed to depend on the PI at that age. We used the PI at 12 months for correction of serum concentrations at age 11 and 18 months. Further, the concentrations at age 5 years were adjusted for whale meat intake. We also adjusted for sex and for interaction between sex and breastfeeding variables.

Serum-PFAS concentrations at birth were collected differently and may therefore have been less precise than the subsequent concentrations. In a sensitivity analyses, we therefore allowed the birth concentrations to have a larger variance than concentrations obtained later. This was done by modifying equation (1) to include a normally distributed random effect which is non-zero only for concentrations at birth (a=0).

All test probabilities were two-sided, and we calculated 95% confidence intervals using robust standard errors. Although only 12 children have complete PFAS information, the mixed model analysis also includes information for in-complete cases under an assumption that data are missing at random20. These statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

All samples contained measurable concentrations of all five PFAS compounds (Table 1). The children were breastfed exclusively for a median of 4.5 months (interquartile range, IQR: 3.5 months; 6 months), followed by partial breastfeeding with supplementary baby food for a median of 4 months (IQR: 2 months; 7 months). More than two-thirds of the children had eaten whale by age 5.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 81 members of the Faroese birth cohort with serum-PFAS concentrations at birth and at ages 11, 18, and 60 months.

| Birth | Age 11 months | Age 18 months | Age 60 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N (%) | Median (IQR) | N (%) | Median (IQR) | N (%) | Median (IQR) | N (%) | Median (IQR) |

| Sex (Number, girls (%)) |

81 (100%) | 32 (39.5%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Age (months) | 81 (100%) | 0 (0,0) | 68 (83.95%) | 10.8 (10.8,10.8) | 70 (86.42%) | 17.3 (16.7,18.4) | 76 (93.83%) | 59.4 (59.1,59.8) |

| PI (kg/m3) | 81 (100%) | 22.5 (21,23.9) | 69 (85.19%) | 21.7 (20.6,23.0) | 69 (85.19%) | 21.7 (20.6,23.0) | 76 (93.83%) | 14.7 (13.9,15.5) |

| Whale intake (Number, yes (%)) |

-- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 74 (91.36%) | 53 (70.7%) |

| Breast-feeding (months) | ||||||||

| Exclusively | 81 (100%) | 0 | 73 (90.12%) | 4.5 (3.5,6.0) | 73 (90.12%) | 4.5 (3.5,6.0) | 73 (90.12%) | 4.5 (3.5,6.0) |

| Partial | 81 (100%) | 0 | 73 (90.12%) | 4.0 (2.0,5.0) | 73 (90.12%) | 4.0 (2.0,7.0) | 73 (90.12%) | 4.0 (2.0,7.0) |

| None | 81 (100%) | 0 | 75 (92.59%) | 1.8 (0,5.3.0) | 75 (92.59%) | 8.7 (5.2,11.5) | 75 (92.59%) | 50.3 (47.6,54.4) |

| Serum concentration (ng/mL) | ||||||||

| PFOS | 80 (98.77%) | 6.0 (5.2,7.2) | 68 (83.95%) | 23.2 (14.9,34.7) | 33 (40.74%) | 24 (20.2,29.1) | 71 (87.65%) | 13.3 (10.6,16.6) |

| PFOA | 80 (98.77%) | 2.0 (1.7,2.7) | 68 (83.95%) | 8.2 (6.1,10.9) | 33 (40.74%) | 6.1 (5.1,10) | 71 (87.65%) | 3.8 (3.1,4.9) |

| PFHxS | 80 (98.77%) | 1.9 (1.3,2.8) | 68 (83.95%) | 0.8 (0.5,1.1) | 33 (40.74%) | 0.8 (0.6,1.0) | 71 (87.65%) | 0.5 (0.3,0.7) |

| PFNA | 80 (98.77%) | 0.3 (0.2,0.4) | 68 (83.95%) | 0.8 (0.4,1.1) | 33 (40.74%) | 0.8 (0.5,1.0) | 71 (87.65%) | 0.9 (0.8,1.2) |

| PFDA | 80 (98.77%) | 0.1 (0.1,0.1) | 68 (83.95%) | 0.2 (0.1,0.3) | 33 (40.74%) | 0.2 (0.1,0.2) | 71 (87.65%) | 0.3 (0.2,0.4) |

Count and percentage.

Abbrevations: Median, geometric mean. IQR, interquartile range. PI, ponderal index

EBJ jeg har indsat to gange “.0” – jeg håber at det er rigtigt – undgå dette format en anden gang.

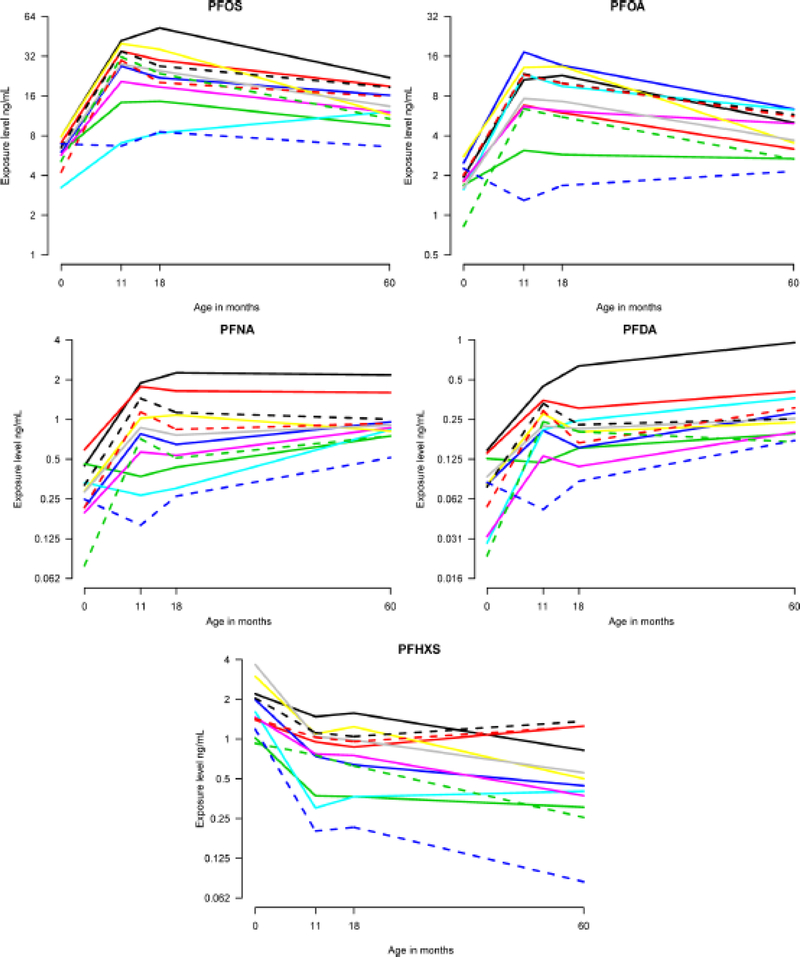

We considered the 81 children who had at least one measurement of serum-PFAS concentrations at ages 11 or 18 months. Table 1 shows the characteristics of these children. Figure 1 shows the trajectories of the five major PFAS for the 12 children with complete observations from all examinations. The child with the lowest concentrations (blue dotted line) was not breastfed at all, whereas the child with the highest PFOS concentration (black solid line) was breastfed exclusively in 6 months and was partially breastfed during the following 5 months.

Figure 1:

PFAS trajectories for 12 children with complete data on serum-PFAS concentrations at ages 0, 11, 18, and 60 months. Note the different exposure scales.

Results of the linear mixed models are shown in Table 2 (left columns). In the models that include only birth, age 11 and age 18 months concentrations, a general increasing trend was found for all PFASs, with exception of PFHxS. During months with exclusive breastfeeding, significant increases in the concentrations of four PFASs occurred, ranging between 18.1% (95%CI: 12.5%, 24.1%) for PFDA to 29.2% (95%CI: 25.3%, 33.1%) for PFOS per month. For months with partial breastfeeding, the PFAS concentrations showed less apparent, though still significant increases, and only small, if any, increases were associated with the number of months without any breastfeeding. In contrast, PFHxS showed a decrease in the serum concentration during all three periods, the steepest and highly statistically significant occurring during months without breastfeeding.

Table 2:

Percentage change in serum-PFAS concentrations per month during exclusive breast-feeding, partial, and none.

| Mixed model up to 18 months | Mixed model up to 60 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS (ng/mL) | Variable | Change | 95%CI | p-value | Change | 95%CI | p-value |

| PFOS | Exclusive | 29.2 | (25.3, 33.1) | <.0001 | 30.2 | (26.2, 34.3) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 4.4 | (1.0, 7.8) | 0.0108 | 1.0 | (−1.2, 3.2) | 0.3762 | |

| None | 0.7 | (−0.5, 1.9) | 0.2693 | −0.9 | (−1.2, −0.6) | <.0001 | |

| PFOA | Exclusive | 27.8 | (23.6, 32.1) | <.0001 | 31.2 | (28.0, 34.5) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 3.9 | (0.5, 7.3) | 0.0252 | 0.1 | (−1.6, 1.9) | 0.8951 | |

| None | 0.7 | (−1.1, 2.5) | 0.4528 | −1.3 | (−1.5, −1.0) | <.0001 | |

| PFHXS | Exclusive | −1.0 | (−7.9, 6.3) | 0.7723 | −7.5 | (−12.1, −2.7) | 0.0032 |

| Partial | −4.2 | (−8.9, 0.7) | 0.0874 | 1.3 | (−1.4, 4.0) | 0.3518 | |

| None | −9.3 | (−10.9, −7.6) | <.0001 | −1.2 | (−1.5, −1.0) | <.0001 | |

| PFNA | Exclusive | 20.8 | (15.7, 26.1) | <.0001 | 19.6 | (15.9, 23.3) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 5.2 | (1.0, 9.6) | 0.0172 | 2.9 | (0.7, 5.3) | 0.0108 | |

| None | −1.5 | (−2.8, −0.2) | 0.0303 | 0.7 | (0.5, 1.0) | <.0001 | |

| PFDA | Exclusive | 18.1 | (12.5, 24.1) | <.0001 | 16.1 | (12.2, 20.1) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 4.8 | (0.2, 9.7) | 0.0412 | 3.3 | (0.8, 5.8) | 0.0099 | |

| None | −0.2 | (−2.7, 2.4) | 0.8924 | 1.3 | (0.9, 1.6) | <.0001 | |

To follow the longer-term development of serum-PFAS concentrations after weaning, we also included the age-5 serum concentrations (Table 2, right columns). The months with exclusive or partial breastfeeding showed similar effects on the age-60 months serum concentrations as in the models based only on the infancy data. Overall, the development of the PFAS concentrations during months without breast feeding showed significant decreases for PFHxS, PFOA, and PFOS.

Assuming that no further exposure occurs, the slope of the (log-) curve for months without breast milk can be interpreted as a reflection of the biological half-life of the serum-PFAS concentration. We find that the child’s serum concentration has decreased by half of the peak concentration at the completion of breast feeding after approximately 22 months (PFHxS), almost 50 months (PFOA), and more than 52 months (PFOS).

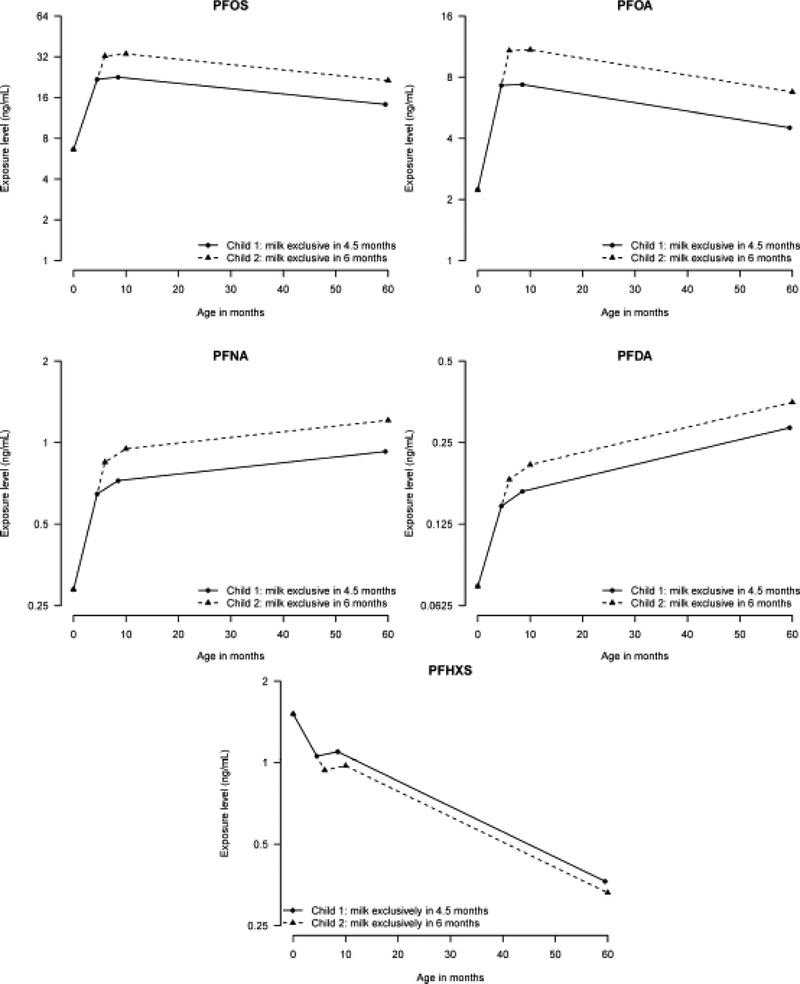

Predicted time-dependent serum-PFAS concentrations are shown in Figure 2 for two children who differ only in number of months with exclusive breastfeeding; one being exclusively breastfed for 4.5 months (median duration in the cohort) and one for 6 months (duration recommended by WHO14), neither of them having ever having eaten whale by age 5 years.

Figure 2:

Predicted PFAS trajectories for two children breastfed exclusively for 4.5 months (average for the cohort) and 6 months (WHO recommendation), both being partially breastfed during the subsequent 4 months.

After adjustment for the child’s PI, sex and whale intake, the changes in serum-PFAS concentrations during breast-feeding and after weaning were almost unchanged (Table 3). The PI showed a positive, though borderline significant association with the serum-PFOA concentration, while the association with the other four PFASs was negative and not statistically significant. The children who consumed at least one whale meal before age 5 had up to 31.9% (95%CI: −6.9%, 86.6%) higher serum-PFAS concentrations compared to the children who had not eaten whale, but there was no statistically significant difference in the PI between children who had eaten whale and those who had not. Also we found no statistically significant differences between boys and girls in PFAS concentrations levels (Table 3) and interaction terms with breast feeding variables were also not significant. Finally, the sensitivity analysis allowing for additional variation in concentrations at birth did not lead to important changes in the estimated effects of breastfeeding variables.

Table 3:

Percentage change in serum-PFAS concentrations per month during exclusive breast-feeding, partial, and none, as compared to the effect of a 10% increase in ponderal index (PI) and whale intake. All results are adjusted for changes in PI and whale intake.

| Mixed model up to 18 months | Mixed model up to 60 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS (ng/mL) | Variable | Change | 95%CI | p-value | Change | 95%CI | p-value |

| PFOS | Exclusive | 30.0 | (26.0, 34.0) | <.0001 | 30.5 | (26.4, 34.8) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 3.2 | (0.0, 6.5) | 0.0481 | 0.6 | (−1.5, 2.7) | 0.6021 | |

| None | 1.0 | (−0.1, 2.2) | 0.0738 | −0.9 | (−1.4, −0.3) | 0.0012 | |

| PI | −3.5 | (−7.7, 0.9) | 0.1137 | −0.2 | (−4.8, 4.6) | 0.9251 | |

| Whale | -- | -- | -- | 0.2 | (−17.3, 21.4) | 0.9834 | |

| Sex (boy vs girl) | −4.9 | (−16.0, 7.7) | 0.4248 | −4.3 | (−16.8, 10.0) | 0.5349 | |

| PFOA | Exclusive | 29.0 | (24.8, 33.4) | <.0001 | 29.7 | (25.6, 34.0) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 2.6 | (−0.4, 5.7) | 0.0893 | 0.1 | (−2.1, 2.5) | 0.9059 | |

| None | 0.8 | (−1.0, 2.7) | 0.3909 | −0.6 | (−1.1, 0.0) | 0.0567 | |

| PI | 0.5 | (−4.8, 6.1) | 0.8555 | 5.3 | (0.0, 10.8) | 0.0479 | |

| Whale | -- | -- | -- | −2.8 | (−20.6, 19.1) | 0.7851 | |

| Sex (boy vs girl) | −6.0 | (−20.8, 11.6) | 0.4762 | −2.0 | (−17.6, 16.6) | 0.8206 | |

| PFHXS | Exclusive | −3.6 | (−10.2, 3.4) | 0.2990 | −7.5 | (−12.5, −2.2) | 0.0060 |

| Partial | −2.0 | (−6.5, 2.7) | 0.3972 | 0.9 | (−2.1, 4.0) | 0.5539 | |

| None | −9.1 | (−10.8, −7.3) | <.0001 | −2.4 | (−3.4, −1.4) | <.0001 | |

| PI | 2.7 | (−5.2, 11.2) | 0.5081 | −3.6 | (−11.0, 4.4) | 0.3688 | |

| Whale | -- | -- | -- | 31.9 | (−6.9, 86.8) | 0.1189 | |

| Sex (boy vs girl) | −0.3 | (−17.8, 21.0) | 0.9794 | 10.0 | (−12.3, 38.1) | 0.4071 | |

| PFNA | Exclusive | 21.1 | (15.5, 26.9) | <.0001 | 20.5 | (16.5, 24.6) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 4.3 | (−0.1, 8.9) | 0.0530 | 2.5 | (−0.1, 5.1) | 0.0606 | |

| None | −1.0 | (−2.0, 0.1) | 0.0838 | 0.3 | (−0.1, 0.8) | 0.1581 | |

| PI | −4.9 | (−9.6, 0.2) | 0.0579 | −2.1 | (−6.3, 2.3) | 0.3393 | |

| Whale | -- | -- | -- | 15.3 | (−10.2, 48.2) | 0.2622 | |

| Sex (boy vs girl) | 7.3 | (−11.0, 9.2) | 0.4380 | 8.6 | (−7.7, 27.8) | 0.3160 | |

| PFDA | Exclusive | 17.3 | (11.1, 23.8) | <.0001 | 16.3 | (12.1, 20.7) | <.0001 |

| Partial | 4.7 | (−0.5, 10.1) | 0.0732 | 2.9 | (0.1, 5.9) | 0.0452 | |

| None | 0.6 | (−1.5, 2.8) | 0.5608 | 1.0 | (0.5, 1.5) | 0.0002 | |

| PI | −4.3 | (−9.8, 1.6) | 0.1374 | −1.2 | (−5.7, 3.5) | 0.6022 | |

| Whale | -- | -- | -- | 11.2 | (−11.4, 39.7) | 0.3564 | |

| Sex (boy vs girl) | 0.2 | (−17.5, 21.6) | 0.9869 | 0.1 | (−14.1, 16.7) | 0.9875 | |

Neither were there any statistically significant difference in PFAS concentrations between boys and girls.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed at examining the profile of serum-PFAS concentrations during the first 5 years after birth. Because of the substantial number of children examined in a prospective design, the results add considerable information to current insight into PFAS exposures and kinetics. As PFAS may occur in elevated concentrations in human milk11, 12, as compared to infant formulas4, 10 neonatal exposures were assumed to depend on the duration of breast-feeding21. As we used log scale transformations of PFAS concentrations, the higher milk concentrations from mothers with elevated serum concentrations12, 13 were included in the model by default. However, neither the newborn baby’s PFAS concentrations and the concentrations in milk were measured in this study, which instead relied on the maternal serum concentrations measured at a specified point during pregnancy. Although the reliance on maternal serum may be a limitation of this study, it avoids variability in cord serum associated with gestational age and in milk levels associated with the time of sampling. Our results show that four of the major PFASs tended to increase substantially during the breast-feeding period, thereby suggesting that human milk is a main source of exposure during infancy. The peak serum concentration was reached at the completion of breast-feeding and was relatively greater for PFOA than for PFNA that was greater than for PFDA, thus suggesting a possible dependence on chain length.

However, the steep decrease in the children’s serum-PFHxS concentrations during the nursing period – in contrast to the steep increases for the other PFASs measured – suggest that early postnatal PFHxS exposure in the Faroes mainly originates from sources other than human milk. Although the calculated neonatal serum concentration may have been slightly inaccurate, the results based on all 81 children, whether breastfed or formula-fed, support the trend of decreasing serum concentrations of this PFAS during early childhood in this community. Our study did not attempt to characterize other exposure sources, apart from whale meat intake. Due to the wide variety of PFAS uses,1 multiple indoor sources22 and food items23 can potentially contribute to human exposures, also during childhood. We note that PFHxS has been used to stain-proof upholstery and carpets and therefore also occurs in house dust,24, 25 which may constitute an important exposure source in later childhood and onwards. Such sources may explain the increases in serum-PFHxS concentrations shown in Figure 1. Although this figure is based on only twelve subjects with complete data, the general pattern is similar to those seen in Figure 2 based on the complete study group, where missing data were modeled.

While human milk is unlikely to be the sole source of exposure, a PFAS transfer of 1 μg/kg during 6 months of exclusive breast-feeding6 would support the notion that human milk could be the dominant exposure source for infants. Because the cohort children were breast-fed for different durations, exclusively and partially, we were able to calculate the associations between serum concentrations and lactational exposure. Our results are also in agreement with previous reports that exposures from baby food were negligible.4, 10

The calculated elimination half-lives are in reasonable accordance with previous reports based on serum-PFAS concentration profiles in adults. More specifically, a half-life of 5.4 years for PFOS in retired workers is quite similar to our calculation of 53 months (4.4 years) for children. Likewise, our finding of 50 months (4.2 years) for PFOA in children is reasonably similar, though somewhat higher than estimates for adults of 3.8 years7 and 2.3 years9. However, our finding of 22 months for PFHxS months is much lower than the estimated half-life of 8.6 years in adults7. All of these studies relied on serial serum measurements following a peak exposure, while assuming that subsequent exposures were negligible. As this assumption is likely to be wrong, the half-lives are most probably exaggerated. Also, it should be noted that the present study relied on blood samples obtained from infants and children after parental consent, and that substantial attrition may mean the study population differs in some respects from the background population. Thus, no definite conclusion can be drawn at this point whether elimination kinetics in children differs from adults. Nonetheless, the results support the notion that the PFASs accumulate in the human body, and these data may be useful to extend modeling studies that calculate the long-term build-up of PFASs in the body starting at early development.26

Adverse effects of PFASs reported in children with similar serum-PFAS concentrations include immunotoxicity, as revealed by decreased antibody concentrations toward childhood vaccines2 and increased frequency of common infections27. Given the importance of postnatal development of acquired immune function, the shape of the serum concentration profile may be important for PFAS-associated immune deficits. Our recent study2 focused on serum concentrations measured only prenatally and at age 5 and may therefore have underestimated the impact of the changes in serum-PFAS concentrations during infancy. The results of the present study suggest that future research should more closely monitor early postnatal PFAS exposures, especially during the breast-feeding period.

One final issue is worth consideration. Breast-feeding represents an excretion pathway for the mother, although apparently not for PFHxS. Serial analyses of human milk have shown that concentrations of PFOA and PFOS may decrease by an average of 46% and 18% during 6 months of breast-feeding11. Calculations based on cross-sectional data also support the conclusion that breast-feeding leads to higher serum concentrations in the child and lower in the mother21. These findings suggest that several months of breast-feeding may substantially lower the mother’s own body burden, thereby possibly representing a maternal advantage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH (ES012199); the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (R830758); the Danish Council for Strategic Research (09–063094); and the Danish Environmental Protection Agency as part of the environmental support program DANCEA (Danish Cooperation for Environment in the Arctic).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lindstrom AB; Strynar MJ; Libelo EL, Polyfluorinated compounds: past, present, and future. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, (19), 7954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grandjean P; Andersen E; Budtz-Jørgensen E; Nielsen F; Mølbak K; Weihe P; Heilmann C, Serum Vaccine Antibody Concentrations in Children Exposed to Perfluorinated Compounds. JAMA 2012, 307, (4), 391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barouki R; Gluckman PD; Grandjean P; Hanson M; Heindel JJ, Developmental origins of non-communicable disease: implications for research and public health. Environmental health : a global access science source 2012, 11, (1), 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lankova D; Lacina O; Pulkrabova J; Hajslova J, The determination of perfluoroalkyl substances, brominated flame retardants and their metabolites in human breast milk and infant formula. Talanta 2013, 117, 318–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. EPA., Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition (Final) In U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, : 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raab U; Albrecht M; Preiss U; Volkel W; Schwegler U; Fromme H, Organochlorine compounds, nitro musks and perfluorinated substances in breast milk - results from Bavarian Monitoring of Breast Milk 2007/8. Chemosphere 2013, 93, (3), 461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen GW; Burris JM; Ehresman DJ; Froehlich JW; Seacat AM; Butenhoff JL; Zobel LR, Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environ Health Perspect 2007, 115, (9), 1298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egeghy PP; Lorber M, An assessment of the exposure of Americans to perfluorooctane sulfonate: a comparison of estimated intake with values inferred from NHANES data. Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology 2011, 21, (2), 150–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartell SM; Calafat AM; Lyu C; Kato K; Ryan PB; Steenland K, Rate of decline in serum PFOA concentrations after granular activated carbon filtration at two public water systems in Ohio and West Virginia. Environ Health Perspect 2010, 118, (2), 222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llorca M; Farre M; Pico Y; Teijon ML; Alvarez JG; Barcelo D, Infant exposure of perfluorinated compounds: levels in breast milk and commercial baby food. Environ Int 2010, 36, (6), 584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomsen C; Haug LS; Stigum H; Froshaug M; Broadwell SL; Becher G, Changes in concentrations of perfluorinated compounds, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and polychlorinated biphenyls in Norwegian breast-milk during twelve months of lactation. Environ Sci Technol 2010, 44, (24), 9550–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karrman A; Ericson I; van Bavel B; Darnerud PO; Aune M; Glynn A; Lignell S; Lindstrom G, Exposure of perfluorinated chemicals through lactation: levels of matched human milk and serum and a temporal trend, 1996–2004, in Sweden. Environ Health Perspect 2007, 115, (2), 226–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mondal D; Lopez-Espinosa MJ; Armstrong B; Stein CR; Fletcher T, Relationships of perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctane sulfonate serum concentrations between mother-child pairs in a population with perfluorooctanoate exposure from drinking water. Environ Health Perspect 2012, 120, (5), 752–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Section on B, Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012, 129, (3), e827–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grandjean P; Jensen AA, Breastfeeding and the weanling’s dilemma. Am J Public Health 2004, 94, (7), 1075; author reply 1075–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen TK; Grandjean P; Jorgensen EB; White RF; Debes F; Weihe P, Effects of breast feeding on neuropsychological development in a community with methylmercury exposure from seafood. Journal of exposure analysis and environmental epidemiology 2005, 15, (5), 423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weihe P; Kato K; Calafat AM; Nielsen F; Wanigatunga AA; Needham LL; Grandjean P, Serum concentrations of polyfluoroalkyl compounds in Faroese whale meat consumers. Environ Sci Technol 2008, 42, (16), 6291–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen TK; Andersen LB; Kyhl HB; Nielsen F; Christesen HT; Grandjean P, Association between perfluorinated compound exposure and miscarriage in Danish pregnant women. PLoS One 2015, 10, (4), e0123496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Needham LL; Grandjean P; Heinzow B; Jorgensen PJ; Nielsen F; Patterson DG Jr.; Sjodin A; Turner WE; Weihe P, Partition of environmental chemicals between maternal and fetal blood and tissues. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, (3), 1121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little RJ; Rubin DB, Statistical analysis with missing data. John Wiley & Sons: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mondal D; Weldon RH; Armstrong BG; Gibson LJ; Lopez-Espinosa MJ; Shin HM; Fletcher T, Breastfeeding: a potential excretion route for mothers and implications for infant exposure to perfluoroalkyl acids. Environ Health Perspect 2014, 122, (2), 187–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shoeib M; Harner T; G MW; Lee SC, Indoor sources of poly- and perfluorinated compounds (PFCS) in Vancouver, Canada: implications for human exposure. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, (19), 7999–8005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domingo JL, Health risks of dietary exposure to perfluorinated compounds. Environ Int 2012, 40, 187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato K; Calafat AM; Needham LL, Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in house dust. Environ Res 2009, 109, (5), 518–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Hollander W; Roosens L; Covaci A; Cornelis C; Reynders H; Campenhout KV; Voogt P; Bervoets L, Brominated flame retardants and perfluorinated compounds in indoor dust from homes and offices in Flanders, Belgium. Chemosphere 2010, 81, (4), 478–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loccisano AE; Longnecker MP; Campbell JL Jr.; Andersen ME; Clewell HJ 3rd, Development of PBPK models for PFOA and PFOS for human pregnancy and lactation life stages. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part A 2013, 76, (1), 25–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granum B; Haug LS; Namork E; Stolevik SB; Thomsen C; Aaberge IS; van Loveren H; Lovik M; Nygaard UC, Pre-natal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances may be associated with altered vaccine antibody levels and immune-related health outcomes in early childhood. J Immunotoxicol 2013, 10, (4), 373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]