Abstract

Extensive undertreatment of substance use disorders has focused attention on whether the expansion of eligibility for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has promoted increased coverage and treatment of these disorders. We assessed changes in coverage and substance use disorder treatment among low-income adults with the disorders following the 2014 ACA Medicaid expansion, using data for 2008–15 from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. The percentage of low-income expansion state residents with substance use disorders who were uninsured decreased from 34.4 percent in 2012–13 to 20.4 percent in 2014–15, while the corresponding decrease among residents of nonexpansion states was from 45.2 percent to 38.6 percent. However, there was no corresponding increase in overall substance use disorder treatment in either expansion or nonexpansion states. The differential increase in insurance coverage suggests that Medicaid expansion contributed to insurance gains, but corresponding treatment gains were not observed. Increasing treatment may require the integration of substance use disorder treatment with other medical services and clinical interventions to motivate people to engage in treatment.

Despite the development of effective treatments for common substance use disorders,1,2 only a small fraction of US adults with these conditions receives treatment each year.3 Many factors—including difficulties affording the treatment,4 not perceiving a need for treatment,5 pessimism concerning treatment effectiveness,5 not feeling ready to stop using substances,6 peer pressure and stigma,7 and geographic barriers7—are common reasons for not receiving treatment for substance use disorders. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the two most frequently reported reasons for not receiving treatment are not being ready to stop using substances and not being able to afford the cost.8

Before the 2014 Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion, most low-income people in need of substance use disorder treatment were ineligible for Medicaid.9 By the end of 2014, however, twenty-six states and the District of Columbia had expanded Medicaid eligibility to include nearly all low-income residents with household incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Because low-income people are at increased risk for substance use disorders10 and for not having health insurance,11 the Medicaid expansion provision has been widely viewed as an important potential means of increasing access to substance use disorder treatment, under the presumption that there is pent-up demand for it.12

Previous research has generally confirmed that Medicaid expansion has resulted in significant gains in Medicaid coverage13 and reductions in uninsurance rates14 among low-income people. According to the NSDUH, between 2011–13 and 2014 there was also an increase in Medicaid coverage and a decrease in uninsurance rates among adults with substance use disorders, though this analysis did not relate these changes to residence in a Medicaid expansion state.15 Within individual states, earlier statewide reforms of Medicaid policies, which involved expanding income eligibility,16 have also been linked to increased substance use disorder treatment and decreases in the probability of perceiving an unmet need for it.17 Finally, a recent national insurance claims analysis revealed that Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant increase in filled prescriptions for buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder.18 Yet it is not known whether the Medicaid expansion provision has increased access to Medicaid coverage for low-income adults with substance use disorders or whether it has contributed to an increase in access to treatment.

To investigate these issues, we used a difference-in-differences approach to compare changes in Medicaid coverage, uninsurance, and substance use disorder treatment among low-income adults in states that did and did not expand Medicaid eligibility. We hypothesized that among low-income adults with substance use disorders, starting in 2014 residence in an expansion state would be associated with an increase in Medicaid coverage, a decrease in un-insurance, and an increase in substance use disorder treatment.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCES

The NSDUH is a cross-sectional annual survey of the US population in all fifty states and the District of Columbia. Sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the survey yields estimates of substance use disorders and their treatment among the civilian noninstitutionalized population that are representative at the national and state levels. People without a household address, active-duty military personnel, and residents of institutions are excluded from the sampling frame. The NSDUH uses a multistage sampling design that includes states, regions within states, dwelling units within regions, and individual participants drawn from each dwelling unit. Interviews are conducted using computer-assisted interviewing. The NSDUH data collection protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at RTI International.

The annual mean weighted response rate of the NSDUH in 2008–15 was 65.2 percent (range:55.2–66.8 percent),19 according to the response rate 2 (RR2) definition of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.20

METHODS

We evaluated the effects of Medicaid expansion on the insurance status and treatment rates of low-income adults with common substance use disorders. The analyses compared trends among residents of expansion and non-expansion states before and after the Medicaid policy change took effect (January 2014).We first tested whether expansion state residence was differentially associated with an increase in Medicaid coverage and a decrease in not having insurance. To assess whether the expansion changed the insurance distribution of treated patients, we then evaluated whether Medicaid coverage differentially increased and no insurance coverage differentially decreased among adults receiving substance use disorder treatment in expansion states. Finally, we assessed whether substance use disorder treatment disproportionately increased among adults with substance use disorders in expansion states after Medicaid expansion.

MEDICAID EXPANSION

The independent variable of interest was residence in a state that expanded Medicaid under the ACA by the end of 2014. Based on a legislative review by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, we divided states into those that had or had not implemented expansion of the Medicaid State Plan Amendment provision.21 By the end of 2014, twenty-six states and the District of Columbia had implemented the Medicaid expansion; they are referred to as expansion states. The remaining twenty-four states are referred to as nonexpansion states. (A list of expansion and nonexpansion states is in online appendix exhibit 1.)22 In our primary analysis, states that expanded Medicaid in 2015 were considered nonexpansion states. We performed a sensitivity analysis that excluded respondents in states that expanded Medicaid before 2014 (California, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Washington) and states that expanded Medicaid in 2015 (Alaska, Indiana, and Pennsylvania).

HEALTH INSURANCE AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER TREATMENT

The outcome variables were health insurance status at the time of the survey interview and receipt of substance use disorder treatment in the past twelve months as reported by survey respondents. We focused on the percentages of adults with Medicaid and with no health insurance.

Substance use disorder treatment was defined by self-reported treatment received for illicit drug or alcohol use or for medical problems associated with that use. Treatment included services received in the past year within a hospital (inpatient), rehabilitation facility (outpatient or inpatient), mental health center, emergency department, private physician’s office, or other organized settings. Because of our focus on services reimbursed by insurance, services provided in prison or jail or by self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous were not considered substance use disorder treatment in the primary analyses.

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS AND SOCIODEMO-GRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Based on diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), the NSDUH provides estimates of past-year dependence on or abuse of alcohol, marijuana (cannabis), cocaine, and heroin. The test-retest reliabilities of the NSDUH interviews were assessed in a randomly selected subsample of 3,136 participants in the 2006 NSDUH. Kappa values for past-year alcohol use disorder (dependence or abuse) (0.64), cannabis use disorder (0.63), and cocaine use disorder (0.64)23 fell in the substantial range of agreement.24 Although a kappa value for heroin use disorder was not assessed, that for lifetime use of heroin (0.95) fell in the almost perfect range. Because of changes in the survey design of the 2015 NSDUH, it was not possible to assess trends associated with other substance use disorders assessed by the NSDUH during the study period.25

Low-income adults were defined based on self-reported household incomes of no more than 138 percent of poverty, following the eligibility threshold for Medicaid in the ACA expansion provision. We used income and household size as reported by NSDUH respondents during the relevant survey year to determine whether household income was no more than 138 percent of poverty. The survey also collected information on respondents’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education level.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To provide context, baseline sociodemographic characteristics were first compared between low-income populations ages 18–64 in expansion and nonexpansion states. For the primary analyses, we restricted the low-income populations to those that met our criteria for having one or more substance use disorders (alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, or heroin). We used a quasi-experimental difference-in-differences design26 with state as a fixed effect to account for unobserved state heterogeneity and national secular trends in insurance status and substance use treatment that might be correlated with residence in a Medicaid expansion state. To increase power, pairs of survey years were combined. The difference-in-differences period difference of interest was 2012–13 to 2014–15. Earlier control-period differences (2008–09 to 2010–11 and 2010–11 to 2012–13) were also examined to establish baseline rates, assess variations before expansion implementation, and confirm the parallel paths assumption27 inherent in the validity of difference-indifferences designs (that is, trends in expansion and nonexpansion states were similar before Medicaid expansion).

Multivariable logistic regression models were used for estimation and included categorical survey years, an expansion state dummy variable, an interaction term for year and expansion state, and covariates (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, and state) as independent variables. Adjusted difference estimates in prevalence (back-transformed from marginal log-odds)28 were used to test change over time within expansion and nonexpansion states. The interaction contrast on the predicted prevalence scale from the model provided the difference-in-differences test of whether the changes over time differed between expansion and nonexpansion states.

To account for the NSDUH’s complex sample design and sample weights, we used SAS-Callable SUDAAN.

LIMITATIONS

This study had some limitations. First, although the NSDUH permits the evaluation of trends in the prevalence and treatment of four common substance use disorders, a change in survey design prevented us from examining trends in the insurance coverage and treatment of adults with prescription stimulant, sedative, or opioid use disorders.

Second, the NSDUH does not cover homeless people not living in shelters, active-duty military personnel, or people residing in institutions. The following measured effects of Medicaid expansion on the civilian non-institutionalized population might not generalize to these populations.

Third, although the NSDUH provides a large, nationally representative sample for study, its sample sizes limited our power to detect policy-related effects on treatment, given low baseline rates of treatment.

Fourth, states’ Medicaid coverage for substance use disorder treatment varies widely, and many states do not cover all levels of care that may be required for effective treatment.29 For example, inpatient rehabilitation might not be Medicaid reimbursable because of the federal Institutions for Mental Diseases exclusion, which prohibits Medicaid financing of substance abuse or mental health residential treatment facilities with more than sixteen beds, and substance use treatment in private physician office visits may be restricted because of Medicaid managed care arrangements in several states.

Fifth, although the NSDUH questions about services cover a wide range of treatment settings, they do not capture services provided at health centers or other outpatient medical clinics that may offer brief substance use disorder interventions.

Finally, the analysis did not assess the effects of Medicaid expansion on the general health and well-being of adults with substance use disorders. In the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, Medicaid expansion was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms, an increase in self-reported mental and physical health and overall well-being, and a reduction in medical debt.30,31

Study Results

BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS

We compared the characteristics of respondents with one or more of four substance use disorders (alcohol, cannabis, heroin, or cocaine). Compared to respondents in nonexpansion states, those in expansion states were more likely to be female and Hispanic and to have cannabis or heroin use disorders, and they were less likely to have alcohol use disorders (exhibit 1). Similar racial/ethnic differences were evident in the overall population of low-income residents of expansion and nonexpansion states (appendix exhibit 2).22 The following trend analyses of low-income adults with substance use disorders were adjusted for sociodemographic differences between the expansion and nonexpansion state groups.

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics of low-income adults with selected substance use disorders in 2008–15, in states that did and did not expand eligibility for Medicaid

| Expansion states | Nonexpansion states | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Percent | SE | Percent | SE | p value |

| Age range (years) | 0.16 | ||||

| 18–24 | 38.7 | (0.89) | 37.4 | (1.10) | |

| 25–34 | 25.9 | (0.84) | 24.3 | (0.92) | |

| 35–44 | 15.8 | (0.77) | 15.3 | (0.88) | |

| 45–64 | 19.6 | (0.97) | 23.0 | (1.19) | |

| Sex | 0.02 | ||||

| Male | 60.9 | (0.92) | 63.9 | (0.94) | |

| Female | 39.1 | (0.92) | 36.1 | (0.94) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 48.8 | (1.02) | 54.6 | (1.17) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17.7 | (0.77) | 23.3 | (0.96) | |

| Hispanic | 25.2 | (0.94) | 16.8 | (0.93) | |

| Other | 8.3 | (0.51) | 5.3 | (0.43) | |

| Education level | 0.09 | ||||

| Less than high school | 30.4 | (0.88) | 30.4 | (0.98) | |

| High school graduate | 29.4 | (0.91) | 27.9 | (1.03) | |

| Some college | 10.4 | (0.57) | 8.7 | (0.53) | |

| College graduate | 29.7 | (0.96) | 32.9 | (1.11) | |

| Substance use disorders in past year | |||||

| Alcohol | 79.5 | (0.73) | 82.3 | (0.79) | 0.01 |

| Cannabis | 26.1 | (0.77) | 23.1 | (0.83) | 0.007 |

| Cocaine | 7.5 | (0.53) | 8.7 | (0.68) | 0.15 |

| Heroin | 5.0 | (0.47) | 2.4 | (0.31) | <0.0001 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NOTES Low-income adults are those with incomes of no more than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Selected disorders include alcohol, cannabis (marijuana), heroin, and cocaine use disorders. Expansion states are those that expanded Medicaid in 2014 or earlier. There were 8,100 respondents in expansion states and 6,300 in nonexpansion states. p values from chi-square statistics. Because the age groups are mutually exclusive groups, one test statistic was computed; the individual substance use disorders are not mutually exclusive groups, so separate test statistics were computed. SE is standard error.

TRENDS IN MEDICAID COVERAGE AND UNINSURANCE RATES

Trends in coverage before and after Medicaid expansion were compared between low-income adults with substance use disorders in expansion and nonexpansion states. As displayed in appendix exhibit 3,22 the increase in Medicaid coverage from 24.5 percent in 2012–13 to 38.5 percent in 2014–15) (trend: p < 0:001) among those in expansion states was not significantly larger than the corresponding increase from 14.2 percent to 19.8 percent (trend: p < 0:05) among those in nonexpansion states (adjusted difference-in-differences: 5.3 percent; 95% confidence interval: −1.8, 12.4).

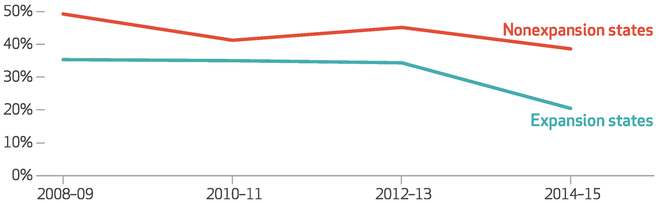

During this period, the percentage of expansion-state residents with substance use disorders who wereuninsured decreased from 34.4 percent to 20.4 percent, a change that was significantly larger than the corresponding decrease among nonexpansion state residents from 45.2 percent to 38.6 percent (exhibit 2). These results were little changed in sensitivity analyses that excluded respondents in states that expanded Medicaid before 2014 or in 2015 (see appendix exhibits 4–6).22

Exhibit 2. Percent of low-income adults with selected substance use disorders who were uninsured in 2008–15, in states that did and did not expand eligibility for Medicaid.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NOTES Low-income adults are those with incomes of no more than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Selected disorders are defined in the notes to exhibit 1. The results were adjusted for respondents’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, state, and education level. The decrease in uninsurance rates in expansion states (defined in the notes to exhibit 1) from 2012–13 to 2014–15 was significant (p < 0:001) and was also significantly larger (p < 0:05) than the decrease in nonexpansion states in the same period (estimated difference-in-differences: −10.4; 95% confidence interval: −17.34, −4.04).

By comparison, as displayed in appendix exhibit 7,22 the increase in Medicaid coverage among the general population of low-income adults was significantly larger between 2012–13 and 2014–15 in expansion states than in non-expansion states, as was the decrease in un-insurance among low-income residents.

TRENDS IN COVERAGE OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER TREATMENT

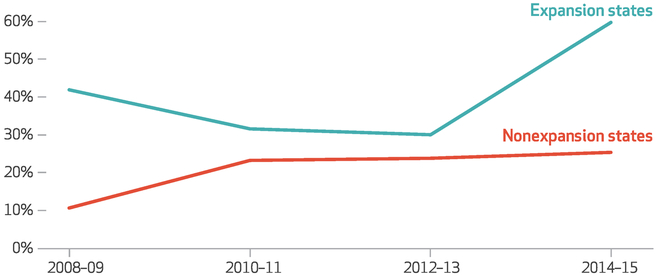

We examined whether changes in Medicaid coverage of low-income adults with substance use disorders coincided with changes in coverage of those who received treatment. Among low-income adults who were treated for their substance use disorders, the percentage in expansion states who had Medicaid coverage nearly doubled from 2012–13 to 2014–15 (30.1 percent versus 59.7 percent), while it remained nearly unchanged among their counterparts in nonexpansion states (an increase from 23.8 percent to 25.4 percent) (exhibit 3). The increase in the percentage of adults with treated substance use disorders who had Medicaid coverage was significantly larger in expansion than in nonexpansion states. Similar results (appendix exhibit 8)22 were observed in the sensitivity analysis that excluded respondents in early and late expansion states.

Exhibit 3. Percent of low-income adults with selected substance use disorders who received any substance use disorder treatment in the past year and who were covered by Medicaid in 2008–15, in states that did and did not expand eligibility for Medicaid.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NOTES Low-income adults are those with incomes of no more than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Selected disorders are defined in the notes to exhibit 1. The results were adjusted for respondents’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, state, and education level. The increase in Medicaid coverage in nonexpansion states from 2008–09 to 2010–11 was significant (p < 0:05) and was also significantly different (p < 0:001) from the change in expansion states (defined in the notes to exhibit 1) (estimated difference-in-differences: −27.1%; 95% confidence interval: −25.34, −28.86). The increase in Medicaid coverage in expansion states from 2012–13 to 2014–15 was significant (p < 0:001) and was also significantly different (p < 0:05) from the increase in nonexpansion states in the same period (estimated difference-in-differences: 31.8; 95% CI: 10.04, 53.56).

During the earlier pre-expansion time periods, there was a significant increase in nonexpansion states in the percentage of low-income adults treated for their substance use disorders who had Medicaid coverage (from 10.7 percent in 2008–09 to 23.3 percent in 2010–11). This increase stands in contrast to the decline in Medicaid coverage of such adults in expansion states (from 41.9 percent to 31.6 percent) (exhibit 3). In the sensitivity analysis that excluded respondents in early and late expansion states, however, the corresponding trends in nonexpansion states and the difference-in-differences analysis were no longer significant (appendix exhibit 8).22

The percentage of low-income adults with treated substance use disorders in expansion states who were uninsured declined from 33.5 percent in 2012–13 to 12.3 percent in 2014–15 (trend: p < 0:05) (appendix exhibit 9).22 This change was not significantly different from the change in the corresponding percentages of such adults innonexpansionstates (from 47.0 percent to 31.4 percent; trend: p = 0:47). In a sensitivity analysis that excluded early and late expansion states, a somewhat larger decrease (from 37.0 percent to 7.5 percent; trend: p < 0:001) occurred in the same period in the percentage of low-income adults with treated substance disorders without health insurance (appendix exhibit 10).22

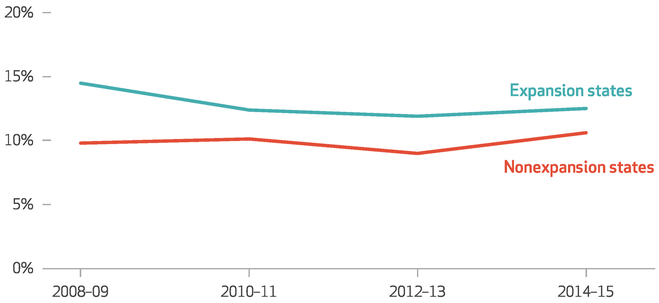

TRENDS IN SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER TREATMENT

There was no significant change from 2012–13 to 2014–15 in the percentages of low-income adults with substance use disorders who reported receiving treatment for them in either expansion or nonexpansion states. In both groups of states, only one in ten such adults received any substance use disorder treatment during the twelve months before the survey interview (exhibit 4). Similar results were observed in the sensitivity analysis that excluded states that expanded Medicaid before 2014 or 2015 (appendix exhibit 11).22 Similar results were also observed in an analysis that expanded the definition of substance use treatment to include self-help (appendix exhibit 12).22

Exhibit 4. Percent of low-income adults with selected substance use disorders who received any substance use disorder treatment in the past year in 2008–15, in states that did and did not expand eligibility for Medicaid.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NOTES Low-income adults are those with incomes of no more than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Selected disorders and expansion states are defined in the notes to exhibit 1. The results were adjusted for respondents’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, state, and education level.

Discussion

In the first two years following implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion, there was a substantial reduction in people who were uninsured among low-income adults with common substance use disorders in expansion states. There was also a reduction in these states in the share of low-income adults treated for substance use disorders who lacked health insurance that might have lowered their out-of-pocket spending. The gains in coverage, however, did not translate into a discernible increase in the percentage of low-income adults with substance use disorders who received treatment for them. This suggests that coverage may be necessary but is not by itself sufficient to meaningfully increase entry into substance use disorder treatment.

These results further suggest that outreach and enrollment efforts within expansion states succeeded in enrolling previously uninsured adults with substance use disorders who were eligible for Medicaid. The gains in Medicaid enrollment for these adults in expansion states were similar to the gains among all low-income adults. With approximately one in five of the income-eligible adults in expansion states un-insured in 2014–15, there were still many people with substance use disorders who were eligible for coverage but did not receive it. Because the NSDUH asks survey respondents about service use during the past year, only a relatively brief period of policy implementation—which started in January 2014 for most expansion states—was captured in the 2014 and 2015 surveys.

In the expansion states, adults with Medicaid coverage accounted for an increasing share of patients who received substance use disorder treatment. By 2014–15 over half of these low-income adults were covered by Medicaid. With the decline in and restructuring of other public funding for substance use services, such as block grants and local public funding, the role of Medicaid is becoming more important—especially in expansion states. These changes in financing create incentives for freestanding substance use treatment programs, which have not historically relied on third-party billing, to participate in Medicaid managed care provider networks, bill Medicaid directly, or affiliate themselves with mainstream general health services that bill Medicaid.12 As of spring 2014, however, only around one in ten such programs had signed agreements with patient-centered medical homes, and virtually all of these agreements had occurred in Medicaid expansion states.32

The slow pace of integration of freestanding substance use treatment programs may constrain the effects of Medicaid insurance gains in facilitating access to substance use services. In some areas of the country, there are few options for Medicaid beneficiaries to receive substance use treatment. Around 40 percent of US counties have no outpatient treatment facilities that accept Medicaid.33 States’ limits on Medicaid substance use benefits29 and the slow and uneven promulgation of Medicaid mental health and substance use parity regulations34 may have also impeded the effects of Medicaid insurance gains on access to substance use services.

Beyond service-related constraints in access to Medicaid-covered substance use disorder treatment, individual-level attitudinal factors (including problem recognition, desire for help, and treatment readiness) likely play an important role in treatment seeking for substance use problems.35 Among people who perceive a need for treatment, 41.2 percent say they are not ready to stop using substances—the most commonly reported reason for not seeking treatment.6 The effects of health insurance on treatment seeking for substance use disorder may be largely confined to people who are ready to enter treatment. For example, cocaine users who describe themselves as being ready for treatment are significantly more likely to report an inability to pay as a barrier to treatment, compared to users who are not ready to enter treatment.36

A clinical focus on identifying personal barriers to change may help motivate treatment acceptance among people with substance use problems. A brief primary care intervention that incorporates motivational interviewing, which helps patients explore and resolve ambivalence concerning their reasons for initiating treatment, has decreased substance use and increased readiness to start treatment.37 Beyond enrolling low-income adults with substance use disorders in Medicaid, additional ways to accelerate entry into treatment may include integrating specialized substance use services with other health services, implementing interventions to increase readiness to accept treatment, and making efforts to lower the stigma attached to treatment. However, it should also be recognized that some adults with alcohol use disorder, particularly those with high levels of social support, achieve remission at long-term follow-up without treatment.38

Conclusion

These results provide an early assessment of the effects of the 2014 ACA Medicaid expansion on insurance coverage and on treatment of common substance use disorders. Coincident with implementation of the expansion provision, there was a disproportionate decline in uninsurance rates among low-income adults in expansion states with common substance use disorders and an increase in Medicaid enrollment. Despite this increase in health insurance, the proportion of the adults who received treatment did not increase. In light of persistently high levels of untreated substance use disorders, it will be important to track national trends in treatment patterns and outcomes, as clinical and public policy experience with the Medicaid expansion population matures over the next several years.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant No. R01 DA039137).

Contributor Information

Mark Olfson, Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, and a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, both in New York City..

Melanie Wall, Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University..

Colleen L. Barry, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in Baltimore, Maryland..

Christine Mauro, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University..

Ramin Mojtabai, Department of Mental Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health..

References

- 1.Connor JP, Haber PS, Hall WD. Alcohol use disorders. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):988–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(1):39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Household Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2010. [cited 2018 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHNationalFindingsResults2010-web/2k10ResultsRev/NSDUHresultsRev2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mojtabai R, Crum RM. Perceived unmet need for alcohol and drug use treatments and future use of services: results from a longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013; 127(1–3):59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han B, Hedden SL, Lipari R, Copello EAP, Kroutil LA. Receipt of services for behavioral health problems: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2015. September [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DRFRR3-2014/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014/NSDUH-DR-FRR3-2014.htm [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masson CL, Shopshire MS, Sen S, Hoffman KA, Hengl NS, Bartolome J, et al. Possible barriers to enrollment in substance abuse treatment among a diverse sample of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: opinions of treatment clients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;44(3): 309–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali MM, Teich JL, Mutter R. Reasons for not seeking substance use disorder treatment: variations by health insurance coverage. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(1):63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Key facts about the uninsured population [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; [updated 2017 Nov 29; cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: http://kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-theuninsured-population [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiology Survey on Alcohol and Related conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2012 [Internet]. Washington (DC): Census Bureau; 2013. September [cited 2018 Jun 1]. (Current Population Report No. P60–245). Available from: https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p60-245.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(8):1402–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ. Both the “private option” and traditional Medicaid expansions improved access to care for low-income adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016; 35(1):96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchmueller TC, Levinson ZM, Levy HG, Wolfe BL. Effect of the Affordable Care Act on racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage. Am J Public Health. 2016; 106(8):1416–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saloner B, Bandara S, Bachhuber M, Barry CL. Insurance coverage and treatment use under the Affordable Care Act among adults with mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(6):542–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zur J, Mojtabai R. Medicaid expansion initiative in Massachusetts: enrollment among substance-abusing homeless adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):2007–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen H, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Effect of Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and access to care among low-income adults with behavioral health conditions. Health Serv Res. 2015; 50(6):1787–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Borders TF, Druss BG. Impact of Medicaid expansion on Medicaid-covered utilization of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment. Med Care. 2017;55(4):336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; [cited 2018 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-useand-health [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 8th ed Oakbrook Terrace (IL): AAPOR; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; 2018. May 31 [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Reliability of key measures in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2010. [cited 2018 Jun 1]. (Office of Applied Studies, Methodology Series M-8, HHS Publication No. SMA 09–4425). Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2k6ReliabilityP/2k6ReliabilityP.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5): 360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2016. September 8 [cited 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: http:///www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM. Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit. 2008;47(1):5–86. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angrist JD, Krueger AB. Empirical strategies in labor economics. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D, editors. Handbook of labor economics, volume 3A Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1999. p. 1277–366. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010; 171(5):618–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grogan CM, Andrews C, Abraham A, Humphreys K, Pollack HA, Smith BT, et al. Survey highlights differences in Medicaid coverage for substance use treatment and opioid use disorder medications. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2289–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: evidence from the first year. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3): 1057–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, et al. The Oregon experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18): 1713–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Aunno T, Pollack H, Chen Q, Friedmann PD. Linkages between patient-centered medical homes and addiction treatment organizations: results from a national survey. Med Care. 2017;55(4):379–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to Medicaid substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):190–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wen H, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Gaydos LM, Druss BG. State parity laws and access to treatment for substance use disorder in the United States: implications for federal parity legislation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1355–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapp RC, Xu J, Carr CA, Lane DT, Redko C, Wang J, et al. Understanding treatment readiness in recently assessed, pre-treatment substance abusers. Subst Abus. 2007; 28(1):11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zule WA, Lam WK, Wechsberg WM. Treatment readiness among out-of-treatment African-American crack users. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003; 35(4):503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mason M, Pate P, Drapkin M, Sozinho K. Motivational interviewing integrated with social network counseling for female adolescents: a randomized pilot study in urban primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41(2):148–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCutcheon VV, Kramer JR, Edenberg HJ, Nurnberger JI, Kuperman S, Schuckit MA, et al. Social contexts of remission from DSM-5 alcohol use disorder in a high-risk sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(7):2015–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.