Abstract

Background

Osteotomies have been performed for centuries yet there remains a remarkable lack of consensus on optimal methods for cutting bone. There is universal agreement, however, that preserving cell viability is critical.

Purpose

To identify mechanobiological parameters influencing bone formation after osteotomy site preparation.

Materials and Methods

A murine maxillary osteotomy model was used to evaluate healing. Computational modeling characterized stress and strain distributions in the osteotomy, as well as the magnitude and distribution of heat generated by drilling. The impact of osteocyte death and bone composition were assessed using molecular and cellular assays.

Results

The phases of osteotomy healing in mice align closely with results in large animals; in addition, molecular analyses extended our understanding of osteoprogenitor cell proliferation, differentiation and mineralization. Computational analyses provided insights into temperature changes caused by drilling and the mechanobiological state in the healing osteotomies, while concomitant cellular assays correlate drill speed with osteocyte apoptosis and bone resorption. Even when drilling was controlled, trabeculated, spongy (Type III) bone healed faster than densely lamellar (Type I) bone because of the abundance of Wnt responsive osteoprogenitor cells in the former.

Conclusions

These data provide a mechanobiological framework for evaluating tools and technologies designed to improve osteotomy site preparation.

INTRODUCTION

Successful implant osseointegration begins with optimal osteotomy site preparation1–3. For example, when an osteotomy is prepared using high-speed rotating instruments the resulting heat can damage the bone and vasculature, which delays new bone formation4, 5. An awareness of these detrimental effects has led to the adoption of methods to limit thermal injury e.g., the use of sharp drilling tools6, irrigation7, 8, and slow drilling speeds9. Piezoelectric devices have also been developed to avoid some of the disadvantages of rotating instruments, but detailed analyses show no clear advantage compared to conventional drilling tools10. Lasers, too, have been developed for similar reasons, with both advantages and limitations compared to drilling tools11, 12.

Other techniques that attempt to improve osteotomy site viability have been tested. Rather than drilling, an initial osteotomy can be enlarged using specialized cutting tools13 or by forcibly advancing an osteotome into a pilot hole14. These types of condensation procedures may increase interfacial bone volume/total volume (BV/TV)15, but a common error is to assume that interfacial bone with a higher BV/TV will provide better initial support greater to an implant16. “Densifying” interfacial bone by condensation can damage the connectivity of bony trabeculae15, and an extensive literature demonstrates that damaged bone is significantly weaker than intact bone17–20. Consequently, implants placed in such osteotomies do not exhibit better primary- or secondary- stability13, 15.

Although osteotomy site preparation has been studied for decades, there remains a remarkable lack of consensus on what constitutes an optimal method to cut bone. It is universally agreed, however, that preserving the structure of interfacial bone translates into better primary stability for an implant, and that preserving cell viability- in both hard and soft tissues- reduces bone turnover. This served as the launching point for our study: to establish quantifiable metrics by which to rigorously assess methods of osteotomy site preparation. We used in vivo models to test clinically relevant drilling speeds and protocols, then used computational modeling to understand how heat generated during drilling impacted new bone formation in an osteotomy site. We used a validated mouse model of oral osteotomy site preparation21–23, which permitted detailed molecular, cellular, and histomorphometric assessment of the entire program of osteotomy healing. Results from these studies established the phases of osteotomy healing, the untoward consequences of high speed drilling on osteocyte viability, and how the rate of osteotomy healing differs depending on the Type of bone being cut. We also identified potential methods for improving osteotomy site preparation, which we propose can have a significant impact on osseointegration success.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animals

Protocols were approved by the Stanford Committee on Animal Research. Every effort was taken to ensure the guiding principles of the three R’s were followed24. Wherever possible, animals were replaced with quantitative in vitro assays and mathematical modeling. Power analyses were used to determine sample size; coupled with careful design, the study supported a reduction in the number of animals. Refinement was addressed by reducing suffering through the use of analgesics25. CD1 wild-type, and Axin2LacZ/+26 6-week-old female mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with 12h light/dark cycles and, after maxillary 1st molar (e.g., M1) extractions and after osteotomy site preparation, were fed a soft food diet and water ad libitum. There was no evidence of infection or prolonged inflammation at the surgical sites.

Tooth extraction and osteotomy site preparation

In total, 60 mice were used for the surgical portion of this study. Mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups as described in Supplemental Table 1. Every effort was taken to minimize pain and/or discomfort by using appropriate anesthetics and analgesics. Mice were anaesthetized with inhalation of 2% isoflurane followed by an intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine (80mg/kg) and Xylazine (16mg/kg), combined with sub-cutaneous injections of buprenorphine (0.1mg/kg).

A split mouth design was employed. After rinsing with a povidone-iodine solution for 1 min, maxillary first molars (M1) were extracted with forceps; bleeding was stopped by local pressure. Extraction sockets were fully healed by 4 weeks27, after which bilateral osteotomies were created in two locations: either the healed M1 site (which represents Type III bone27), or on the edentulous ridge (which represents Type I bone27). There is significant clinical skill required to produce such small osteotomies in a precise manner; consequently, the drilling procedure was practiced repeatedly on mouse carcasses before being carried out on anesthetized animals. Drills were 0.3mm in diameter (Dill bit city, Chicago, IL, USA). Drill speeds are as indicated in Supplemental Table 1. After surgery, mice received sub-cutaneous injections of buprenorphine (0.1mg/kg) for analgesia 2×/day for three successive days. No evidence of infection or prolonged inflammation was detected.

Modeling heat transfer during drilling

A two-dimensional axisymmetric computational model was constructed. An annulus constituted the region of interest (ROI) and had the following boundary conditions and dimensions, which were derived from µCT data of the osteotomy site: the inner radius, ri = 0.15mm; outer radius, ro = 0.5mm; and height, H = 1.0mm. The top and bottom boundaries were assumed to be insulated and the temperature at the right boundary and the initial temperature in the domain were set to 37°C. A feed rate for the drill was chosen that increased with an increase in rotational speed (e.g., 0.5mm/s for 1,000rpm drilling and 0.8mm/s for 40,000rpm drilling). The heat flux, estimated from reference28 was applied to the left boundary where the tip of the drill was located. Below the drill tip, the value of heat flux was set to zero, and a convection boundary condition was applied above the drill tip. The temperature distribution in the bone was calculated by numerically solving the two-dimensional transient heat conduction equation in cylindrical coordinates, using a finite difference method and Euler scheme for time-stepping.

Mechanical analysis of osteotomy sites

To define the mechanobiological environment of healing osteotomies, a 3D finite element (FE) model was formulated (Comsol 5.2a) to represent key structural features of one-half of the murine maxilla. The geometry of the FE model was based on data from µCT data then simplified as a truss-type structure whose members were 1.6mm in height (z-direction) and 2.7mm in depth (x-direction). The length of the member representing the “ridge” of the maxilla (in the y-direction) was 11.8mm, while the lengths of the anterior and posterior sides of the triangular structure were 9mm and 6mm, respectively. A 0.3mm diameter osteotomy was made in the edentulous ridge, which is comprised of Type I bone. The linearly elastic, isotropic properties used for the FE model were as follows: truss members were assigned a Young’s modulus (E) and Poisson’s ratio (ν) of cortical bone, 10GPa and 0.33, respectively. E and ν of the day 1 content (fibrin) and day 2–3 content (fibrin + granulation tissue) of the osteotomies were 50kPa and 0.33 and 0.1MPa and 0.3329, 30, respectively. The distal-most end of the maxillary structure was then fixed while a vertical bite force of 5N was applied at the incisal end in a positive z-direction, which simulated the incisal bite force in mice31.

Sample preparation and tissue processing

After sacrifice, tissues were harvested and fixed in the 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Samples were decalcified in 19% EDTA. After complete demineralization, specimens were dehydrated through an ascending ethanol series prior to paraffin embedding. Eight-micron-thick transverse sections were cut and collected on Superfrost-plus slides. Tissue sections prepared for histology, enzymatic activity analysis, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were prepared by one individual then a single investigator was responsible for photography; two blinded and calibrated investigators quantified the specimens.

Histology, enzymatic activity analyses, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Aniline blue, Hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) and Pentachrome staining were used to evaluate the osteoid and new bone formation in each time points32. DAPI staining was used to detect the viable cells. TUNEL staining was used to detect programmed cell death. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity were used to evaluate the bone remodeling. The LacZ product, beta-galactosidase, was detected by immunostaining26. Primary antibodies included Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, ab18197, Abcam, USA), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, ab15323, Abcam, USA) Runt-related transcription factor 2, (Runx2, ab23981, Abcam, USA), Osterix (ab22552, Abcam, USA) and Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70, ab79852, Abcam, USA). After development, slides were dehydrated in a series of ethanol and Citrisolv, cover-slipped with Permount mounting media, and photographed using a Leica digital imaging system.

Histomorphometric analyses

Histomorphometric measurements were performed with Image J software (Version 1.49v). Photography was carried out by a single investigator, while quantification and analyses was conducted by two blinded individuals. A minimum of four Aniline blue-stained tissue sections was used for the quantification of new bone formation in the osteotomy. Each section was photographed using a Leica digital image system at 20× or 40× magnification. An ROI was defined based on the edge of osteotomy. The number of Aniline blue+ve pixels located in the ROI was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the number of pixels in the ROI (i.e., Aniline blue+ve pixels in the ROI/total number of pixels in the ROI). A similar method was used to quantify, Runx2+ve cells, Osterix+ve cells and ALP+ve cells. The number of positive pixels were expressed as a percentage of total pixels in the ROI.

Statistical analyses

Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine significant differences between data sets. A P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant and all statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel software (Version 15.16, USA).

This study followed Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

RESULTS

Establishing the time frame and phases of osteotomy healing

The first osteotomies were created on the edentulous ridge, anterior to M1. Osteotomies were produced using a drill with a diameter of 0.3mm and a dental engine run at 1,000rpm; this translates to a radial velocity of 150 mm/min (2.5 mm/s) which is analogous in humans to the use of a 3.0mm drill being run at 100rpm. This conservative drilling speed was used as a starting point to establish the baseline for the osteotomy site healing response.

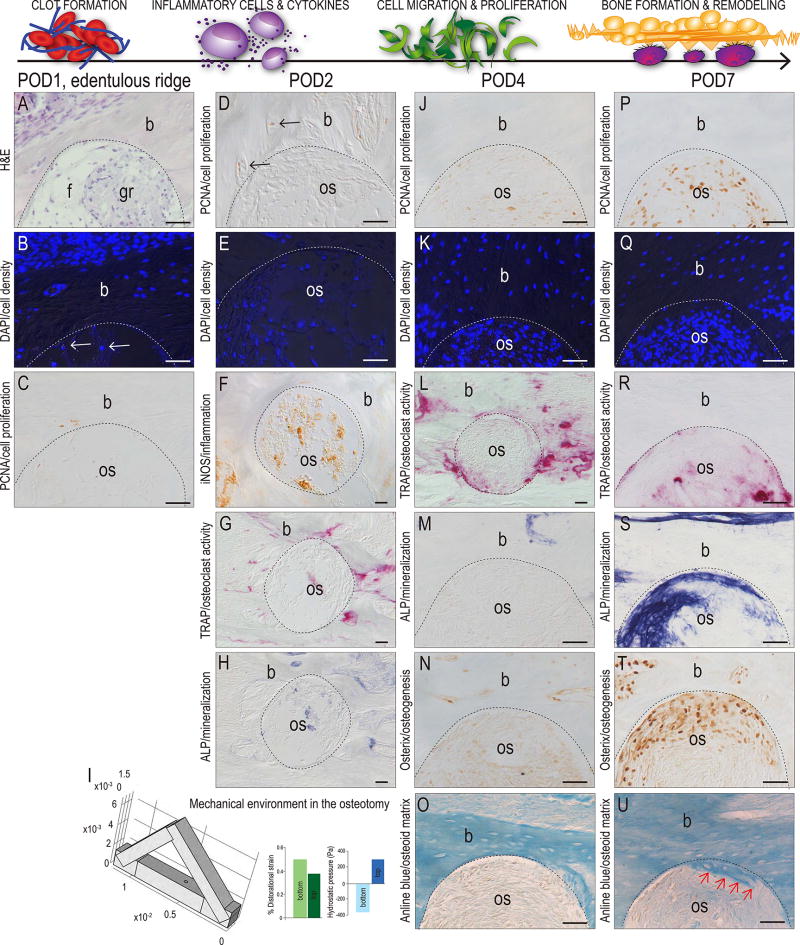

On post-osteotomy day (POD) 1 the site (demarcated by a dotted line) was filled with fibrin, cellular debris, and granulation tissue (Fig. 1A). DAPI staining revealed very few viable cells in the site itself (arrows, Fig. 1B). There was no evidence of mitotic activity as shown by the absence of PCNA immunostaining (Fig. 1C). Thus, the cellular activities at POD1 in the mouse corresponded to the same cellular events reported in large animal and human osteotomies33, 34.

Figure 1. A time course of osteotomy site healing.

(A) H&E staining of the osteotomy site on POD1; here and throughout the figure the edge of the osteotomy is demarcated by a dotted line. (B) DAPI staining for viable cells in the osteotomy and surrounding bone; very few viable cells exist in the osteotomy (arrows). (C) PCNA immunostaining on POD1 and (D) on POD2; arrows indicate immunopositive cells. (E) DAPI staining of viable cells occupying the osteotomy on POD2. (F) iNOS immunostaining of inflammation cells in the osteotomy on POD2. (G) TRAP activity and (H) ALP activity on POD2. (I) 3D finite element model of osteotomy of the murine maxilla, illustrating the magnitude of the distortional strain (green bars) and hydrostatic pressure (blue bars) in the bottom and top of the osteotomy sites. (J) Mitotically active, PCNA+ve cells in the osteotomy coincide with (K) an increase in viable cells by POD4. (L) Compared to POD2, TRAP activity on POD4 is elevated. (M) ALP activity, (N) Osterix expression, and (O) Aniline-positive new osteoid is undetectable on POD4 but (P) on POD7 PCNA+ve cells constitute most the (Q) viable cells in the osteotomy. (R) TRAP-mediated bone remodeling is largely concluded and new bone formation, as shown by (S) ALP activity, (I) Osterix expression and (U) new osteoid matrix (arrows) has commenced by POD7. Abbreviations: f, fibrous tissue; gr, granulation tissue; b, bone; os, osteotomy. Scale bars = 50µm.

By POD2 very few proliferating cells were visible (Fig. 1D) but nucleated cells had replaced red blood cells in the osteotomy site (Fig. 1E). Inflammatory cells were also detectable (Fig. 1F) along with TRAP+ve osteoclasts that had begun to resorb the edges of the osteotomy (Fig. 1G). Minimal ALP activity, which identifies areas undergoing active mineralization, was detectable at POD2 (Fig. 1H). Thus, POD2 corresponded to the beginning of the inflammatory period.

We did not observe any evidence of cartilage in the osteotomy site. In fact, analyses throughout the entire period of analysis confirmed that new bone formation occurred solely through intramembranous ossification. The question was, why? There is an extensive literature in the field of biomechanics that implicates stress/strain history as a key determinant of whether bone healing occurs via intramembranous versus endochondral ossification35, 36. To determine whether the stress/strain history of an oral osteotomy site favored intramembranous versus endochondral ossification we undertook a series of FE simulations to characterize the distortional strain and hydrostatic pressure within the osteotomy site itself. Boundary conditions were based on µCT data from mice and these FE analyses predicted very low distortional strains in both the bottom and top of the osteotomy (green bars, respectively; Fig. 1I), as well as very low hydrostatic pressures in the bottom and top of the osteotomy (blue bars, Fig. 1I). Therefore, the mechanical environment in an oral osteotomy site favors the direct differentiation of cells into osteoblasts.

Histologic analyses supported this prediction. By POD4, cell proliferation was detectable in the osteotomy (Fig. 1J) and was accompanied by a notable increase in cell density site (Fig. 1K). Bone remodeling continued (Fig. 1L) but new bone formation was not yet initiated, as shown by the lack of ALP activity and Osterix expression (Fig. 1M,N) and the deficit of new osteoid matrix (Fig. 1O). By POD7, most cells in the osteotomy were mitotically active (Fig. 1P), which was accompanied by a dramatic increase in cell density (Fig. 1Q). Bone remodeling was on the wane (Fig. 1R) and in its place, strong ALP activity heralded the onset of new bone formation (Fig. 1S). This conclusion was supported by the robust, widespread expression of Osterix (Fig. 1T) and the first evidence of newly mineralized matrix (Fig. 1U). As predicted by FE modeling, no cartilage intermediate was detected at any of the time points examined (data not shown).

When considered together, these molecular data established the phases and timeframe of osteotomy site healing in a rodent model. Clot formation and the inflammatory period spanned from POD0–4, the proliferative phase lasted between POD4–7, and the differentiation phase was in full swing by POD7. Our next series of experiments focused on which aspects of this healing time course were impacted by drilling speed.

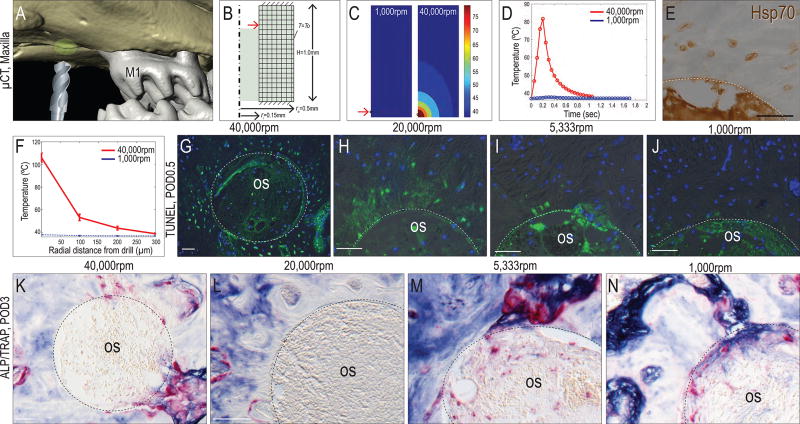

Drilling speed correlates with heat transfer and osteocyte apoptosis

Although it is widely appreciated that high speed drilling impedes osteotomy site healing37 there is minimal data on the relationships between drilling parameters, the amount and distribution of the heat generated, and the biological consequences resulting from that heat transfer. To address these relationships, we constructed a computational model to calculate the magnitude and distribution of temperature elevation due to heat transfer from drilling at different speeds.

Using the same mouse model, an annulus of bone surrounding the osteotomy was selected as the region of interest (ROI; green area, Fig. 2A). Heat generated from the tip of the drill bit was schematized in a computational model, which itself was established from murine µCT data (Fig. 2B). When drilling at 1,000rpm, the average maximum temperature within the ROI was ~38°C (Fig. 2C, left panel). When drilling at 40,000rpm, the average maximum temperature reached ~106°C (Fig. 2C, right panel). The duration of the elevated temperature was calculated; when drilling at 1,000rpm, the temperature was very minimally elevated, and then for only a very short time (0.3sec, blue line, Fig. 2D). When drilling at 40,000rpm, the temperature in bone was maintained above >50°C for twice as long (red line, Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Relationship between drill speed, heat transfer, and programmed cell death around an osteotomy.

(A) Three dimensional reconstruction from µCT data, illustrating the model used to evaluate heat transfer in bone. The ROI is indicated with a green circle and consists of a 3D annulus surrounding the osteotomy site. (B) Schematic of the computational model with the inner radius, ri, outer radius, ro, and the height, H, of the annulus specified as in the in vivo model. (C) Temperature distribution resulting from 1,000rpm and 40,000rpm drilling. (D) Plots illustrating the relationships between drill speed and elevated temperature duration. (E) Hsp70 expression in osteocytes near the osteotomy edge on POD2 following 1,000rpm drilling; dotted line indicates the osteotomy edge. (F) Radial distance from the osteotomy edge of elevated temperatures resulting from different drilling speeds. TUNEL and DAPI staining detect apoptotic and viable cells, respectively on POD0.5 after drilling at (G) 40,000rpm, (H) 20,000rpm, (I) 5,333rpm and (J) 1000rpm. ALP and TRAP co-staining showing bone remodeling on POD7 after drilling at (K) 40,000rpm, (L) 20,000rpm, (M) 5,333rpm and (N) 1000rpm. Abbreviations: M1, maxillary 1st molar; os, osteotomy. Scale bars = 50µm.

The duration of heating measured in milliseconds; we wondered if this would have any biological effect on the bone. In other in vivo systems, thermal injury activates expression of a class of chaperone “heat shock” proteins (HSPs) involved in protecting cells from damage38, and the same was true after drilling in the mouse oral cavity: osteocytes near the osteotomy edge were positive for Hsp70 expression (Fig. 2E). Computational modeling predicted the spatial distribution of elevated temperatures. Compared to drilling at 1,000rpm, which did not lead to temperature elevation (blue line, Fig. 2F) drilling at 40,000rpm created an elevated temperature zone that extended ~130µm radially from the osteotomy edge (red line Fig. 2F). This radial zone of elevated temperatures was reflected in a zone of TUNEL+ve, dying osteocytes (Fig. 2G). Drilling at 20,000rpm also created a zone of cell death, albeit a narrower one (Fig. 2H). Drilling at 5,333rpm and 1,000rpm caused progressively fewer osteocytes to undergo programmed cell death (Fig. 2I,J).

Osteocyte apoptosis triggered bone remodeling. TRAP activity predominated in osteotomies created with 40,000rpm drilling (Fig. 2K). Less TRAP staining was found in osteotomies created with 20,000rpm drilling (Fig. 2L) and this trend continued at the lower drilling speeds (Fig. 2M,N). Concomitantly, there was an increase in ALP activity at low drilling speeds, indicating mineralization predominated over bone resorption (Fig. 2N). At later time points (e.g., POD7), all osteotomies showed evidence of new bone formation.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that as drilling speed increased the duration and magnitude of elevated temperatures in the bone also rose, and both features were associated with an increase in the zone of death, and more pronounced bone resorption.

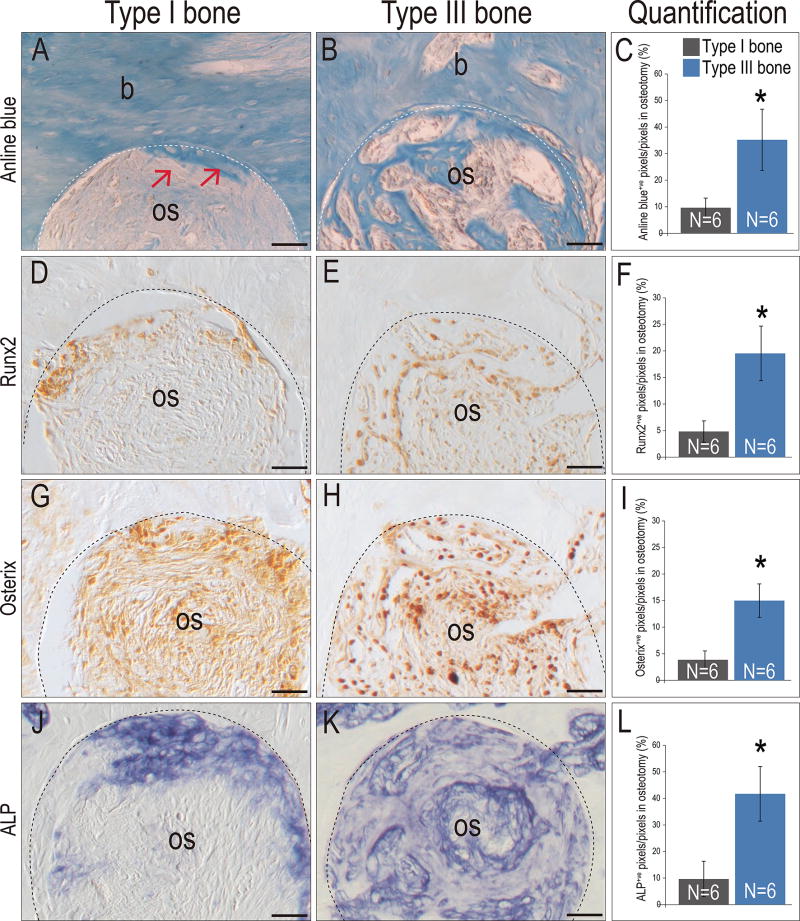

Type III bones heal faster than Type I bones

Bones in the oral cavity have different densities39, and our next analyses focused on whether these differences had an impact on the rate of osteotomy site healing. In previous studies we demonstrated that the murine maxillary edentulous ridge represents dense, lamellar Type I bone and a healed maxillary M1 extraction site represents trabecular Type III bone27. Therefore, using a constant drill speed, we tested whether osteotomy healing differed between these two Types of bone.

Analyses on POD7 showed new osteoid matrix had just initiated on POD7 in Type I sites (arrows, Fig. 3A; see also Fig. 1U). At this same time point, osteotomies created in Type III bone were already filled with new bone matrix (Fig. 3B; quantified in C). Cell commitment to an osteogenic lineage- as shown by immunostaining for the osteogenic proteins Runx2 and Osterix- had just begun in Type I bone osteotomies (Fig. 3D,G) whereas three times more cells in the Type III bone osteotomies were committed to an osteogenic fate (Fig. 3E,H and F,I). ALP activity was also significantly more extensive (a 4-fold increase) in Type III bone osteotomies (compare Fig. 3J–L). The obvious next question was, why did osteotomies in Type III bone heal much more rapidly than osteotomies created in Type I bone?

Figure 3. Osteotomies heal at different rates in Type I versus Type III bones.

On POD7, Aniline blue staining on representative tissue sections from (A) Type I and (B) Type III bone; dotted line indicates the osteotomy edge and red arrows indicates the new osteoid formation near the osteotomy edge. (C) Quantification of Aniline blue+ve pixels in the healing osteotomy. Runx2 expression on representative tissue sections from (D) Type I and (E) Type III bone. (F) Quantification of Runx2+ve pixels in the healing osteotomy. Osterix expression on representative tissue sections from (G) Type I and (H) Type III bone. (I) Quantification of Osterix+ve pixels in the healing osteotomy. ALP staining on representative tissue sections from (J) Type I and (K) Type III bone. (L) Quantification of ALP+ve pixels in the healing osteotomy. Abbreviations: os, osteotomy; b, bone. Scale bars = 50µm.

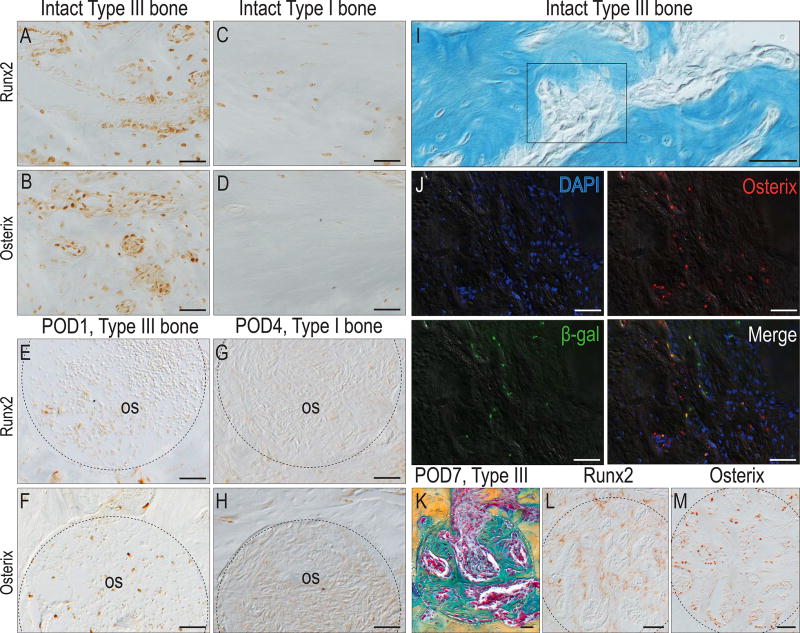

We began with an analysis of the intact bones. Runx2+ve and Osterix+ve osteoprogenitor cells were far more abundant in Type III bone than in Type I bone (compare Fig. 4A,B with C,D). The same observation was made after injury: within 1 day of creating an osteotomy in Type III bone, a few Runx2+ve cells (Fig. 4E), and many more Osterix+ve cells, occupied the injury site (Fig. 4F). Even 4 days after creating an osteotomy in Type I bone, however, Runx2+ve and Osterix+ve cells still had not appeared in the healing site (Fig. 4G,H).

Figure 4. A biological basis for faster osteotomy healing of Type III versus Type I bones.

(A) Runx2+ve and (B) Osterix+ve osteocytes and osteoprogenitor cells in intact Type III bone. (C) Runx2 and (D) Osterix expression in Type I bone. As early as POD1, (E) Runx2+ve and (F) Osterix+ve cells are detectable in healing osteotomies created in Type III bone. On POD4, (G) Runx2 and (H) Osterix expressing cells are almost undetectable in osteotomies created in Type I bone. (I) Osteoprogenitor cells reside by vascular sinusoids. (J) Co-immunostaining with DAPI, Osterix and beta-galactosidase identify Wnt responsive osteoprogenitor cells. (K) On POD7, pentachrome staining identifies new bone formation in osteotomies created in Type III bone. (L) Runx2 and (M) Osterix expression in adjacent tissue sections. Abbreviations: M2, maxillary 2nd molar; os, osteotomy. Scale bars = 50µm.

We located the sites where osteoprogenitor cells resided. Type III bone is penetrated by vascular sinusoids (Fig. 4I) and co-immunostaining with DAPI, Osterix and beta galactosidase to identify Wnt responsive cells27 identified this as the primary location for this osteoprogenitor cell population (Fig. 4J). By POD7, these Runx2+ve and Osterix+ve cells had contributed to the faster healing observed in Type III bone osteotomies (Fig. 4K–M).

DISCUSSION

Ensuring successful osseointegration of an implant begins with optimal osteotomy site preparation. What constitutes ideal site preparation, however, is only superficially defined. Our goals here were first, to characterize the process by which an osteotomy heals and second, to determine how clinically relevant variables such as drill speed and type of bone impacted the healing process.

This study was carried out using a mouse model; consequently, one might legitimately wonder these results are relevant to clinical osteotomy site preparation. To address this issue, we took care to scale drill diameters and used radial velocities instead of rpm when calculating drill speeds to maintain proportional values with clinical protocols. Other factors, such as the intrinsic material properties (e.g., elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio) of murine bones do not substantially differ from those of human bone40. The predictions that emerge from our models involve quantities such as mechanical strain and temperature that “scale” i.e., are translational to similar events in large animals. Strain, for example, is often measured as a percentage change in length, which has the same physical meaning whether the object in question is 100µm or 10mm in length. Likewise, if a given duration of elevated temperatures is found to kill osteocytes in murine bone, a similar exposure will also damage cells in human bone41. In sum, while we no animal species completely recapitulates the response of human tissues to osteotomy site preparation, a rodent model has the potential to provide unique insights into an age-old surgical technique commonly used in humans.

Osteotomy site healing is distinct from fracture repair

There are three notable characteristics that distinguish osteotomy healing from other types of bone repair. Compared to most fractures, an osteotomy site is relatively stable: its mechanical environment is characterized by relatively low distortional strains and hydrostatic pressures (Fig. 1), which favors the direct differentiation of progenitor cells into osteoblasts35, 36. Second, in an osteotomy site, drilling kills osteocytes on the cut bone edge (Fig. 2E–J), which in turn triggers a resorptive process followed by new bone formation (Fig. 2K–N). Although osteocytes are also killed at a fractured bone edge42–44, the zone of death is considerably smaller than that created by drilling (Fig. 2H–J). The third distinction between osteotomy site healing and fracture healing is anatomic location: many studies on dental implant osseointegration- including our own- have been carried out using the long bones as a model system45–47. This ectopic environment, however, differs substantially from the oral cavity: Craniofacial bones exhibit remarkable variability in volume (ranging from abundant to barely sufficient48), and “quality”39, 49 (reviewed in50). For example, bone in the anterior mandible is primarily comprised of homogenous, dense, Type I bone and although it provides excellent primary stability to implants, the lack of a blood supply is known to compromise osseointegration51. Conversely, Type II–III bone is structurally weaker but because of abundant vascular lacunae it supports implant osseointegration39. Data shown here (Figs. 3,4) provide molecular insights into why osseointegration is successful even when bone is porous: vascular spaces in Type II–III bones harbor an abundance of Wnt-responsive osteoprogenitor cells that quickly give rise to new bone (Figs. 3,4). Similar populations are nearly absent in Type I bone and consequently, new bone formation is slower (Figs. 3,4).

One strategy to improve osteotomy site preparation: deform rather than cut bone

It is universally agreed that thermal damage to the bone should be avoided at all costs4; consequently, it is standard practice to employ some means by which to cool the drill tip. Slower speed drilling is helpful (Fig. 2) but it should be emphasized that osteocyte death is not due to friction between the bone and the drill tip33. Rather, the heat generated by cutting is due to energy released in response to the very large deformation involved in cutting chips of the bone37. Therefore, one approach to reducing the amount of osteocyte death (and thereby reducing bone resorption around an implant placed in such an osteotomy) is to limit bone cutting, and instead attempt to deform the bone sufficiently to create room for an implant. Such an approach would have to be primarily employed in less dense, Type III and IV bone as compared to Type I bone.

It is generally thought that the shape of an osteotomy should facilitate maximum implant-to-bone contact52, 53. Our data, however, demonstrate that sites with minimal implant-to-bone contact show the fastest rate of healing (Fig. 3). There are two explanations for this pro-osteogenic response: first, such regions are characterized by low strain54, and in such low strain environments, osteoblast differentiation is significantly faster15, 46. Pre-clinical data from dog studies support this conclusion, where new woven bone formation appeared to be higher in “contact-free” regions around implants53.

The second explanation for the pro-osteogenic response we observe in areas of no/low bone contact is that osteoprogenitor cells are abundant in vascular sinusoids55, which are primarily responsible for creating the voids around an implant (Fig. 4). The abundance and proximity of these cells hastens new bone formation around an implant55. Thus, an implant design that purposefully produces pro-osteogenic regions of low strain may create a superior local environment that favors osseointegration.

A second strategy to improve osteotomy site preparation: enhance the reparative potential of the bone

If the mechanical environment is identical, and the drilling speed is consistent, there is nonetheless a significant difference in the healing potentials based on the Type of bone being cut (Fig. 3). Even though the two bone Types used in this study were separated by only millimeters, they nonetheless show radically different healing potentials (Fig. 3). Our subsequent analyses suggested why this was the case (Fig. 4). Trabeculated Type III bone is filled with vascular sinusoids and Wnt responsive osteoprogenitor cells were abundant in these spaces (Fig. 4). In sharp contrast, Type I bone was nearly devoid of the progenitor cell population (Fig. 4 and see55). In other studies, we showed that these osteoprogenitors can be mobilized and recruited to contribute to new bone formation around an implant56, even if that implant is in a gap-type interface created in Type I bone57. This leads to our second approach towards improving osteotomy site preparation: in bone Types that have compromised osteogenic potential- either because of patient factors such as age, metabolic disease, or habits such as smoking, new bone formation may be accelerated by the delivery of a pro-osteogenic protein such as WNT3A26, 32, 58.

CONCLUSIONS

Implant osseointegration can be improved by optimizing osteotomy site preparation. To aid clinicians in achieving superior osteotomy site viability we provide a mechanobiological framework for the evaluation of new tools and technologies designed to enhance bone formation in an osteotomy, and thus improve implant success.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by a grant from NIH (R01DE024000-11, J.A.H. and J.B.), from National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1102700, L.W.) and from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600910, L.W.). We thank Yan Wu, Xibo Pei, Chih hao Chen and Bo Liu for invaluable aid in performing histology and data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept/Design (L.W. and J.A.H.), Data analysis/interpretation (L.W., M.A., J.B. and J.A.H.), Drafting article (L.W. and J.A.H.), Data collection and statistics (L.W. and M.A.) Critical revision and approval of article (L.W., M.A., J.B. and J.A.H.).

References

- 1.Yeniyol S, Jimbo R, Marin C, Tovar N, Janal MN, Coelho PG. The effect of drilling speed on early bone healing to oral implants. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giro G, Marin C, Granato R, Bonfante EA, Suzuki M, Janal MN, Coelho PG. Effect of drilling technique on the early integration of plateau root form endosteal implants: an experimental study in dogs. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2158–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salina S, Maiorana C, Iezzi G, Colombo A, Fontana F, Piattelli A. Histological evaluation, in rabbit tibiae, of osseointegration of mini-implants in sites prepared with Er: YAG laser versus sites prepared with traditional burs. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2006;16:145–156. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v16.i2.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eriksson A, Albrektsson T, Grane B, McQueen D. Thermal injury to bone. A vital-microscopic description of heat effects. Int J Oral Surg. 1982;11:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(82)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews LS, Hirsch C. Temperatures measured in human cortical bone when drilling. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:297–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuijthof GJ, Fruhwirt C, Kment C. Influence of tool geometry on drilling performance of cortical and trabecular bone. Med Eng Phys. 2013;35:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isler SC, Cansiz E, Tanyel C, Soluk M, Selvi F, Cebi Z. The effect of irrigation temperature on bone healing. Int J Med Sci. 2011;8:704–708. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tawy GF, Rowe PJ, Riches PE. Thermal Damage Done to Bone by Burring and Sawing With and Without Irrigation in Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1102–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaba T, Suganami T, Ikebe K, Sogo M, Maeda Y, Wada M. The Evaluation of the Heat Generated by the Implant Osteotomy Preparation Using a Modified Method of the Measuring Temperature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2015;30:820–826. doi: 10.11607/jomi.3990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esteves JC, Marcantonio E, Jr, de Souza Faloni AP, Rocha FR, Marcantonio RA, Wilk K, Intini G. Dynamics of bone healing after osteotomy with piezosurgery or conventional drilling - histomorphometrical, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis. J Transl Med. 2013;11:221. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leucht P, Lam K, Kim JB, Mackanos MA, Simanovskii DM, Longaker MT, Contag CH, Schwettman HA, Helms JA. Accelerated bone repair after plasma laser corticotomies. Ann Surg. 2007;246:140–150. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000258559.07435.b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker S. Surgical lasers and hard dental tissue. Br Dent J. 2007;202:445–454. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huwais S, Meyer EG. A Novel Osseous Densification Approach in Implant Osteotomy Preparation to Increase Biomechanical Primary Stability, Bone Mineral Density, and Bone-to-Implant Contact. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2016 doi: 10.11607/jomi.4817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Summers RB. A new concept in maxillary implant surgery: the osteotome technique. Compendium. 1994;15:152, 154–156. 158 passim; quiz 162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Wu Y, Perez KC, Hyman S, Brunski JB, Tulu US, Bao C, Salmon B, Helms JA. Effects of condensation on peri-implant bone density and remodeling. Journal of Dental Research. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0022034516683932. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenstein G, Cavallaro J, Greenstein B, Tarnow D. Treatment planning implant dentistry with a 2-mm twist drill. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2010;31:126–128. 130. 132 passim; quiz 137-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabel J, Odgaard A, Van Rietbergen B, Huiskes R. Connectivity and the elastic properties of cancellous bone. Bone. 1999;24:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keaveny TM, Wachtel EF, Guo XE, Hayes WC. Mechanical behavior of damaged trabecular bone. J Biomech. 1994;27:1309–1318. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardisty MR, Zauel R, Stover SM, Fyhrie DP. The importance of intrinsic damage properties to bone fragility: a finite element study. J Biomech Eng. 2013;135:011004. doi: 10.1115/1.4023090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szabo ME, Zekonyte J, Katsamenis OL, Taylor M, Thurner PJ. Similar damage initiation but different failure behavior in trabecular and cortical bone tissue. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4:1787–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin X, Li J, Chen T, Mouraret S, Dhamdhere G, Brunski JB, Zou S, Helms JA. Rescuing failed oral implants via Wnt activation. J Clin Periodontol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mouraret S, Hunter DJ, Bardet C, Brunski JB, Bouchard P, Helms JA. A pre-clinical murine model of oral implant osseointegration. Bone. 2014;58:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouraret S, Houschyar KS, Hunter DJ, Smith AA, Jew OS, Girod S, Helms JA. Cell viability after osteotomy and bone harvesting: comparison of piezoelectric surgery and conventional bur. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43:966–971. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Animal Research: Reporting of in vivo experiments. Vol. 2016. National Centre for the Replacement Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research London; England: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearce AI, Richards RG, Milz S, Schneider E, Pearce SG. Animal models for implant biomaterial research in bone: a review. Eur Cell Mater. 2007;13:1–10. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v013a01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minear S, Leucht P, Jiang J, Liu B, Zeng A, Fuerer C, Nusse R, Helms JA. Wnt proteins promote bone regeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:29ra30. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Yin X, Huang L, Mouraret S, Aghvami M, Brunski JB, Salmon B, Helms JA. Relationships among bone quality, implant osseointegration, and Wnt signaling. Journal of Dental Research. doi: 10.1177/0022034517700131. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abayazid M. Modelling heat generation and temperature distribution during dental surgical drilling. Masters, Delft University of Technology, Biomedical Engineering. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haworth KJ, Weidner CR, Abruzzo TA, Shearn JT, Holland CK. Mechanical properties and fibrin characteristics of endovascular coil-clot complexes: relevance to endovascular cerebral aneurysm repair paradigms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7:291–296. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-011076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaksson H, van Donkelaar CC, Ito K. Sensitivity of tissue differentiation and bone healing predictions to tissue properties. J Biomech. 2009;42:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Druzinsky RE. Functional anatomy of incisal biting in Aplodontia rufa and sciuromorph rodents - part 1: masticatory muscles, skull shape and digging. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;191:510–522. doi: 10.1159/000284931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mouraret S, Hunter DJ, Bardet C, Popelut A, Brunski JB, Chaussain C, Bouchard P, Helms JA. Improving oral implant osseointegration in a murine model via Wnt signal amplification. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:172–180. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carvalho AC, Queiroz TP, Okamoto R, Margonar R, Garcia IR, Jr, Magro Filho O. Evaluation of bone heating, immediate bone cell viability, and wear of high-resistance drills after the creation of implant osteotomies in rabbit tibias. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011;26:1193–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.dos Santos PL, Queiroz TP, Margonar R, Gomes de Souza Carvalho AC, Okamoto R, de Souza Faloni AP, Garcia IR., Jr Guided implant surgery: what is the influence of this new technique on bone cell viability? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garzon-Alvarado DA, Gutierrez ML, Calixto LF. A computational model of clavicle bone formation: a mechano-biochemical hypothesis. Bone. 2014;61:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferretti M, Palumbo C, Bertoni L, Cavani F, Marotti G. Does static precede dynamic osteogenesis in endochondral ossification as occurs in intramembranous ossification? Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:1158–1162. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonfield W, Li CH. The temperature dependence of the deformation of bone. J Biomech. 1968;1:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(68)90026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersen LB, Veland IR, Schroder JM, Christensen ST. Assembly of primary cilia. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1993–2006. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lekholm U, Zarb G. Patient selection and preparation. Quintessence Chicago: [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chattah NL, Sharir A, Weiner S, Shahar R. Determining the elastic modulus of mouse cortical bone using electronic speckle pattern interferometry (ESPI) and micro computed tomography: a new approach for characterizing small-bone material properties. Bone. 2009;45:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.03.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dewhirst MW, Viglianti BL, Lora-Michiels M, Hoopes PJ, Hanson M. Thermal Dose Requirement for Tissue Effect: Experimental and Clinical Findings. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2003;4954:37. doi: 10.1117/12.476637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferguson C, Alpern E, Miclau T, Helms JA. Does adult fracture repair recapitulate embryonic skeletal formation? Mech Dev. 1999;87:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miclau T, Lu C, Thompson Z, Choi P, Puttlitz C, Marcucio R, Helms JA. Effects of delayed stabilization on fracture healing. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1552–1558. doi: 10.1002/jor.20435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson Z, Miclau T, Hu D, Helms JA. A model for intramembranous ossification during fracture healing. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meirelles L, Branemark PI, Albrektsson T, Feng C, Johansson C. Histological evaluation of bone formation adjacent to dental implants with a novel apical chamber design: preliminary data in the rabbit model. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015;17:453–460. doi: 10.1111/cid.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cha JY, Pereira MD, Smith AA, Houschyar KS, Yin X, Mouraret S, Brunski JB, Helms JA. Multiscale analyses of the bone-implant interface. J Dent Res. 2015;94:482–490. doi: 10.1177/0022034514566029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leucht P, Kim JB, Wazen R, Currey JA, Nanci A, Brunski JB, Helms JA. Effect of mechanical stimuli on skeletal regeneration around implants. Bone. 2007;40:919–930. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Misch CE, Judy KW. Classification of partially edentulous arches for implant dentistry. Int J Oral Implantol. 1987;4:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linkow LI, Cherchève R. Theories and techniques of oral implantology. C. V. Mosby Co.; Saint Louis: [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donnelly E. Methods for assessing bone quality: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2128–2138. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1702-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Misch CE, Dietsh-Misch F, Hoar J, Beck G, Hazen R, Misch CM. A bone quality-based implant system: first year of prosthetic loading. J Oral Implantol. 1999;25:185–197. doi: 10.1563/1548-1336(1999)025<0185:ABQISF>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stavropoulos A, Cochran D, Obrecht M, Pippenger BE, Dard M. Effect of Osteotomy Preparation on Osseointegration of Immediately Loaded, Tapered Dental Implants. Adv Dent Res. 2016;28:34–41. doi: 10.1177/0022034515624446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berglundh T, Abrahamsson I, Lang NP, Lindhe J. De novo alveolar bone formation adjacent to endosseous implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:251–262. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2003.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albogha MH, Takahashi I. Generic finite element models of orthodontic mini-implants: Are they reliable? J Biomech. 2015;48:3751–3756. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li J, Yin X, Huang L, Mouraret S, Brusnki J, Cordova L, Salmon B, Helms JA. Relationships among bone quality, implant osseointegration & Wnt signaling. Journal of Dental Research. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0022034517700131. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Popelut A, Rooker SM, Leucht P, Medio M, Brunski JB, Helms JA. The acceleration of implant osseointegration by liposomal Wnt3a. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9173–9181. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yin X, Li J, Chen T, Mouraret S, Dhamdhere G, Brunski JB, Zou S, Helms JA. Rescuing failed oral implants via Wnt activation. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43:180–192. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leucht P, Jiang J, Cheng D, Liu B, Dhamdhere G, Fang MY, Monica SD, Urena JJ, Cole W, Smith LR, Castillo AB, Longaker MT, Helms JA. Wnt3a reestablishes osteogenic capacity to bone grafts from aged animals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1278–1288. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.