Abstract

Each year, more than 2 million women are diagnosed with breast or cervical cancer, yet where a woman lives largely determines whether she will develop one of these cancers, have access to timely and effective diagnostic and treatment services, and ultimately survive. Premature death and disability from cancer is a preventable tragedy for hundreds of thousands of women and their families every year. In regions with limited resources, and a fragile or fragmented health system, cancer contributes to the cycle of poverty. This is most striking for cervical cancer, as more than eight in ten women diagnosed and nine in ten women who die from cervical cancer live in a low- or middle-income country. There are proven and cost-effective approaches to reduce these disparities, yet for most women there are few opportunities to access life-saving interventions such as HPV vaccination, and cervical cancer screening with timely treatment of pre-cancerous lesions. These longstanding inequities highlight the urgent need for substantive and sustainable investments in cancer control more broadly, including prevention and early detection programs, capacity building for health service infrastructure and human resources for cancer management including all disciplines: pathology, surgery, radiotherapy, systemic therapy as well as palliative care. Equally vital is the development of high-quality population-based cancer registries, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. In this first Series paper we describe the burden of breast and cervical cancer, with an emphasis on global and regional trends in incidence, mortality and survival; the social and economic impact on women and their families; and the disparities in cancer survival among socioeconomically disadvantaged women in different settings.

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of premature death and disability worldwide, particularly in women1,2. It is a rapidly growing crisis in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the epidemiological transition continues to shift the burden of disease from predominantly infectious causes to chronic, non-communicable diseases (NCDs)3. Many countries, particularly those with weak health systems, are struggling to cope with the rapid rise in non-communicable diseases while still experiencing high maternal and child mortality rates, and high mortality rates from infectious diseases (including malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS) as well as malnutrition.

Globally, more than 2 million women are diagnosed with breast or cervical cancer each year, but where a woman lives, in which country, in areas remote from health care services, and how she lives - poor or otherwise socially disenfranchised - largely determines whether she will develop one of these cancers, how early she presents, and then whether she has access to safe and affordable diagnostic and treatment services. This is particularly striking for cervical cancer, as approximately 85% of women diagnosed and 88% of women who die from cervical cancer live in a LMIC3. There are proven approaches to reduce these disparities, including HPV vaccination to prevent cervical cancer, yet for most women there are few opportunities to access these life-saving interventions. In many countries, and in many lower-resource areas within countries, implementation of HPV vaccination is limited4, as is the availability of, and access to early detection programmes, cancer surgery5, essential cancer medicines6, radiotherapy7, palliative care8, as well as to support for those who survive, sometimes called “survivorship care”.

Disability and premature death from breast or cervical cancer is a preventable tragedy for hundreds of thousands of women and their families each year. In 2012, breast and cervical cancer took the lives of 522 000 and 266 000 women respectively3; as such, close to half a million more women died from these two cancers alone than from complications of pregnancy or childbirth (303 000 maternal deaths in 2015, according to UNFPA)9. A further 152 000 women died from ovarian cancer and 76 000 women from endometrial cancer3. But where do women’s cancers fit on the global health agenda? In high-income countries there is noteworthy advocacy, media attention and funding for research and treatment of cancer, but in many lower-resource settings, breast, cervical and other gynaecological cancers are effectively "neglected diseases"10. That these diseases cause considerable disability, premature death, disruption of family life and loss to the national economy, thus exacerbating the cycle of poverty11, has been largely ignored.

Only 5% of global spending on cancer is directed toward the majority of countries where the greatest burden exists12. Health inequities are differences in health “…that are unnecessary, avoidable, unfair and unjust”13. Poor health within countries and inequities between countries reflect an unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services that result from “ineffective social policies, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics”14. Cancers that primarily affect women present particular challenges in terms of achieving health equity. Elevating the status of women will be one of the key drivers in reducing disparities in cancer outcomes within and between countries.

The Lancet Series on women’s cancers seeks to provide an advocacy and action framework for radically improving progress toward closing the “global cancer divide”11 for women. The three papers will focus on the global burden of breast and cervical cancer (Series paper 1), the untapped potential of proven and promising interventions, the challenges and opportunities to take these to scale while strengthening health systems (Series paper 2), and the provision of recommendations for translating evidence to policy, in order to reduce inequities and improve cancer survival for women (Series paper 3).

In this first paper we describe the burden of breast and cervical cancer, with an emphasis on global and regional trends in incidence, mortality and survival; the social and economic impact on women and their families, and the disparities in cancer survival among socioeconomically disadvantaged women. Endometrial, ovarian, and other gynaecological cancers are important contributors to cancer mortality, but this Series will focus primarily on breast and cervical cancer, as two of the greatest contributors to cancer mortality and morbidity in women worldwide. As highlighted in this review, breast and cervical cancer will continue to pose particularly important challenges, as well as opportunities to strengthen health systems in most countries, for decades to come. Cervical cancer is largely preventable through public health interventions (HPV vaccination and screening with treatment of pre-cancerous lesions), and HPV vaccination of girls is among the few cancer-related so-called “Best Buys” or “very cost effective strategies” according to the World Health Organization’s Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases (2013-2020)15. HPV vaccination and screening and treatment of pre-cancerous cervical lesions are both under consideration for the updated Global Action Plan, and are included in the package of essential interventions for cancer control in LMIC, in the new Cancer Volume of the World Bank Group’s Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (DCP3)16. Although breast cancer screening continues to generate significant debate regarding the magnitude of benefits and harms, opportune ages and screening intervals, cost effectiveness, and relevance to lower resource settings (See Series Paper 2), improving access to early diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer is also being considered for the updated Plan, and promotion of breast cancer early diagnosis and treatment is listed in the DCP3 essential package16. We therefore address only these two cancers in this Series, as they fall under the domains of public health and public policy most relevant to women’s cancers.

Aetiology of breast and cervical cancer

The major known risk factors for breast cancer include female sex, age, and family history, as well as reproductive factors, including early age at menarche, later menopause, nulliparity, and first childbirth after age 30, all of which are independent risk factors17. Breastfeeding is independently associated with a reduced risk, with longer duration associated with a greater relative risk reduction)18. Overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk for post-menopausal breast cancer, while the effect on pre-menopausal breast cancer is not as clear and remains an area of active study19.

The most important risk factor for invasive cervical cancer is the human papilloma virus (HPV), of which there are several major oncogenic subtypes20 (discussed further in Series paper 2). Other independent risk factors include immunosuppression, particularly HIV21, and smoking 22.

Breast and cervical cancer: incidence, mortality and survival

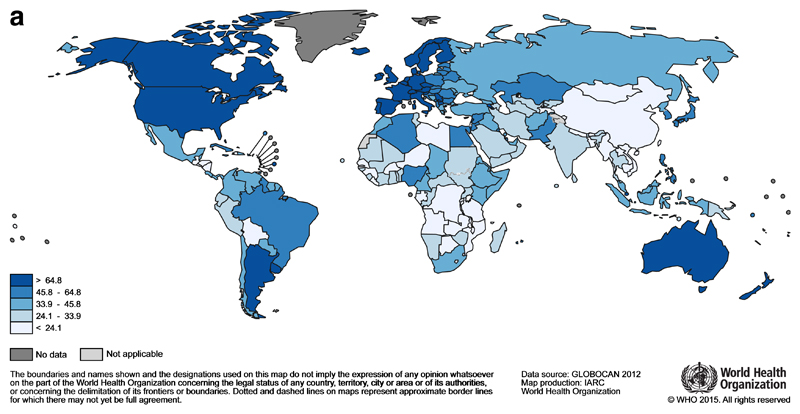

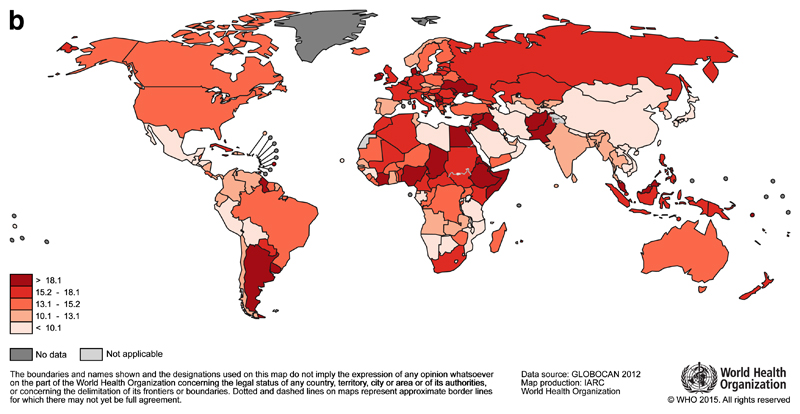

Each year 1.7 million women are diagnosed with breast cancer, making it the most common cancer in women globally3. The highest incidence rates are reported from countries in Northern and Western Europe (e.g. Denmark, Belgium, UK), North America, Australia and New Zealand (Figure 1a), but breast cancer is not confined to high-income countries, and it is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in 140 countries. With an estimated 522 000 deaths in 2012, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in women (15% of all cancer deaths), ahead of lung cancer (491 000 deaths). Breast cancer survival is lower in many LMIC, and mortality rates vary more widely than incidence (Figure 1b). For example, estimated breast cancer mortality rates in the Pacific Islands (Fiji), the Caribbean (The Bahamas), Sub-Saharan Africa (Nigeria) and Southern Asia (Pakistan) are among the highest in the world3.

Fig 1a.

Global map of the age-standardised (world) incidence rates of female breast cancer in 2012, with the range divided into quintiles. Source: GLOBOCAN (http://globocan.iarc.fr)

Fig 1b.

Global map of the age-standardised (world) mortality rates of female breast cancer in 2012, with the range divided into quintiles. Source: GLOBOCAN (http://globocan.iarc.fr)

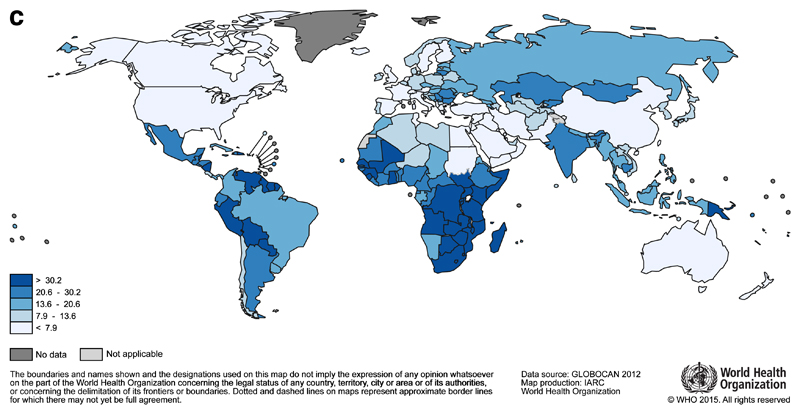

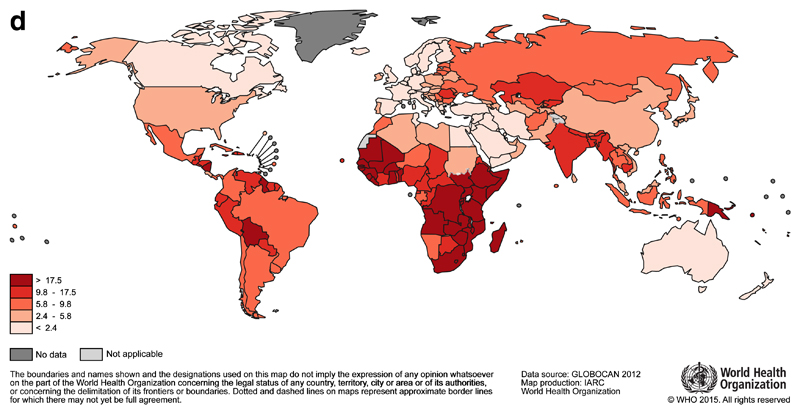

It is estimated that 530 000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer in 20123. It is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide, but in 38 countries, including many in Sub-Saharan Africa, it is the most common cancer among women. The highest incidence rates are observed in this region (Malawi and Zimbabwe, Figure 1c), although rates are also high in parts of Central and South America (Guyana and Bolivia). Unlike breast cancer, the global map of cervical cancer mortality rates is more similar to incidence (Figure 1d).

Fig 1c.

Global map of the age-standardised (world) incidence rates of cervical cancer in 2012, with the range divided into quintiles. Source: GLOBOCAN (http://globocan.iarc.fr)

Fig 1d.

Global map of the age-standardised (world) mortality rates of cervical cancer in 2012, with the range divided into quintiles. Source: GLOBOCAN (http://globocan.iarc.fr)

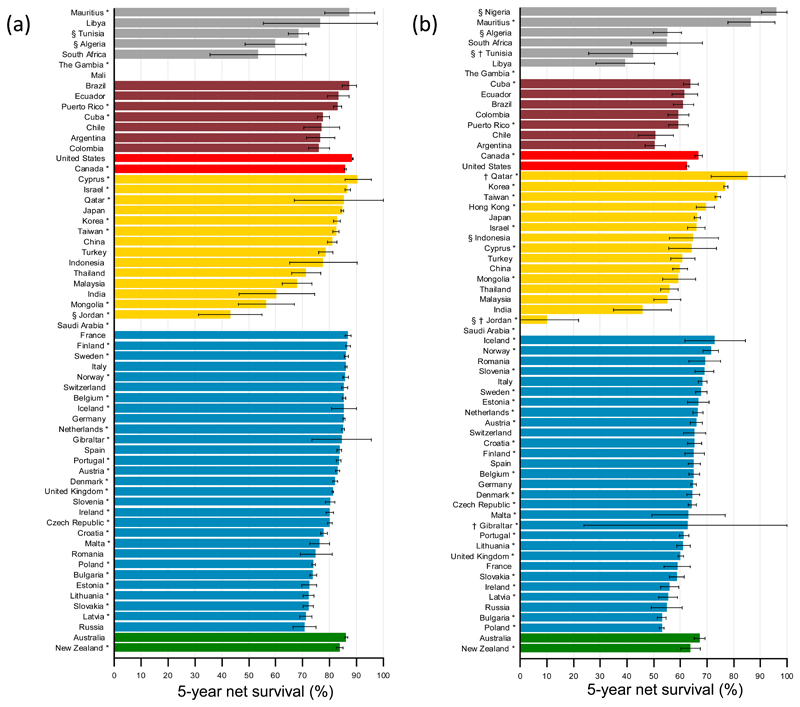

Global surveillance of cancer survival trends was recently initiated by the CONCORD-2 study23 which analysed individual data from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries for over 25 million adults (15-99 years) diagnosed with one of 10 common cancers during the 15-year period 1995-2009. Net survival up to 5 years after diagnosis was estimated after correction for death from other causes. Data were available from 59 countries for almost 5.5 million women diagnosed with breast cancer. For women diagnosed during 2005–2009, 5-year net survival was 80% or higher in 34 countries, but much lower in India (60%), Mongolia (57%) and South Africa (53%) (Figure 2). In the 10 years between 1995-1999 and 2005-2009, 5-year survival from breast cancer increased in Central and South America (e.g. from 66% to 76% in Colombia). Data were available from 61 countries for 602 000 women diagnosed with cervical cancer. The global range in 5-year net survival was very wide. For women diagnosed during 2005-2009, 5-year net survival was 70% or higher in 7 countries, in the range 60–69% in 34 countries, but below 60% in a further 20 countries.

Figure 2.

Global distribution of age-standardised 5-year net survival (%) for women diagnosed aged 15-99 years with (a) breast or (b) cervical cancer during 2005–09, by continent and country.

Legend: Survival estimates for each country are ranked from highest to lowest within each continent: Africa (grey), America (Central and South) (red); America (North) (light red); Asia (yellow); Europe (blue); Oceania (green). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Survival estimates are flagged as follows: *=100% coverage of national population; †=not age-standardised, or §=less reliable because the only estimate(s) available are from a registry or registries in this category.

A large international study followed up cancer patients diagnosed 1990-2001 in 12 transitioning countries and noted similarly wide variations in cancer survival24. They describe 5-year survival for breast cancer by extent of disease: “localized” versus “regional” (indicating larger tumours or local spread to skin, chest wall or regional lymph nodes), for countries with more-developed or less-developed health services. Information on the extent of disease was not available for the African countries in this study. Survival for women with localized disease was reported to be around 90% for countries with highly developed health services (Singapore and Turkey), compared to 76% in countries where they were less developed (Thailand, India and Costa Rica), with a greater disparity for women with regional disease (75.4% versus 47.4% for more- and less-developed health services, respectively).

While each of these studies have certain limitations, they highlight the urgent need for investment in population-based cancer registration, in improving awareness, in early detection programmes, in health-services infrastructure, and increasing capacity including human resources23,24.

Women’s cancers and human development

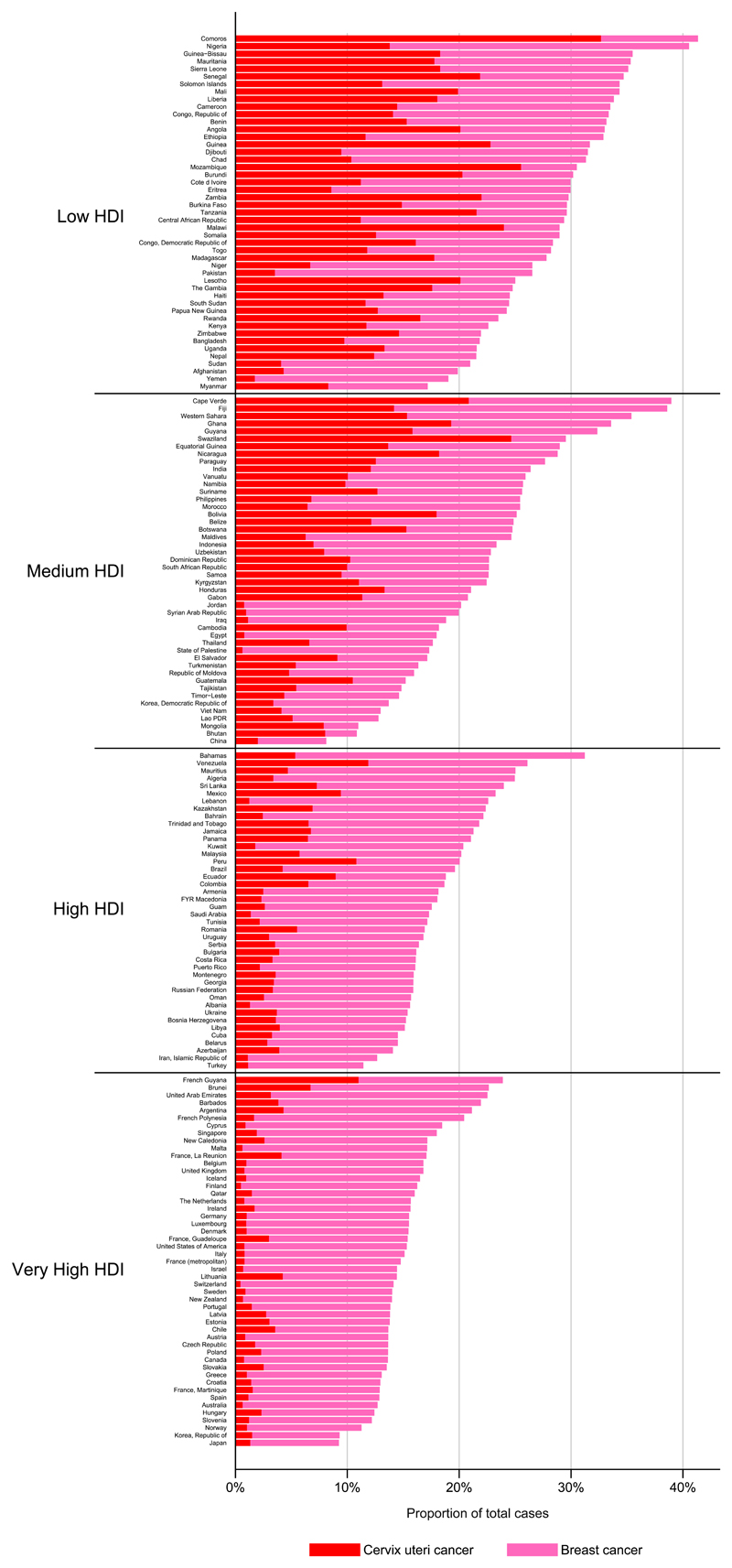

Breast and cervical cancer are indicative of the late phase of the epidemiological transition that characterises the rise of NCDs generally. Increasing life expectancy and declines in infection-related diseases (including cervical cancer) are offset by an upsurge in cancers more frequent in wealthier countries and associated with a "western" environment and lifestyle25,26 referred to as the “ cancer transition”25. The Human Development Index (HDI) is a composite index of three basic dimensions of human development27: a long and healthy life measured by life expectancy at birth, access to knowledge based on a combination of adult literacy rate and primary to tertiary education enrolment rates, and a decent standard of living, based on GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing-power parity (PPP US$). It therefore places an emphasis on societal values and capabilities within a country as well as economic growth. Comparing the national incidence burden of the two diseases by level of (HDI), the inequity is clear: cervical cancer comprises up to one-third of all neoplasms diagnosed (in both sexes) in many low HDI settings, compared with less than 10% in most very high HDI countries (Figure 3). In many low (and some medium) HDI countries, the combined burden of breast and cervical represents one-third of the total cancer burden in women; reductions in cervical cancer to rates observed in very HDI countries would effectively reduce this proportion to 10-15%.

Figure 3.

The proportion of new cases of cervical and breast cancer in 2012 compared with the total cancer burden from all cancers combined in both sexes by country and four-level Human Development Index (HDI), and sort by HDI within these quartiles. Source: GLOBOCAN (http://globocan.iarc.fr)

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in most countries, including many where cervical cancer is endemic. This suggests that breast cancer incidence is largely unrelated to national averages of the HDI. Yet the relative magnitude and the extent to which breast cancer incidence is rising and cervical cancer incidence falling are markers of the extent of social and economic transition in a given country25. Changing reproductive patterns, including earlier age at menarche, later first childbirth, lower parity and shorter duration of breast-feeding are considered to be the major causes for the uniformly rising incidence of breast cancer in transitioning countries26 with overweight and obesity becoming increasingly important factors in post-menopausal breast cancer19. In some high-income countries, mammographic screening has generated transient rises and subsequent falls in breast cancer incidence while declines in the use of hormone replacement therapy (following publication of the Women’s Health Initiative study in 200228) was associated with a period of declining breast cancer incidence, a phenomenon which seems to have stabilized since 200729. Meanwhile, survival has been improving and mortality has been declining in many high-income countries, probably due to a combination of more effective treatments23,30,31 as well as earlier presentation and improved access to care.

Declining cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates in many countries over the last decades are associated with the implementation of effective population-based screening programmes in high-income countries or, in transitioning countries, a diminishing prevalence of factors associated with persistent infection with oncogenic subtypes of the human papilloma virus (HPV)32. However, there are notable exceptions. For example, steady increases in cervical cancer incidence have been observed in the high-risk populations in Uganda33 and Zimbabwe34. Increasing premature cervical cancer mortality is clearly evident from the cohort-specific mortality trends in some countries in Eastern Europe, and Central Asia including former republics of the Soviet Union35.

This “overlapping challenge” whereby breast cancer incidence and mortality are increasing while the burden of cervical cancer is not yet declining is explored with an equity lens in a study from Mexico, using subnational, time series data36. The report emphasizes the need for integrated programmes that consider both prevention and treatment “underpinned by a life cycle approach to effectively respond to the burden of cancer faced by women globally”36.

Singh et al37 reported on global inequities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality as a function of variations in HDI, socioeconomic factors, healthcare expenditures, and the Gender Inequality Index (GII) for 184 countries. GII is a composite score that includes reproductive health (maternal mortality ratio and adolescent birth rates), empowerment (proportion of women in parliament and those with secondary education), and economic status (labour force participation). Incidence and mortality were both correlated with human development and gender inequality. A 0.2 unit increase in GII was associated with a 24% increased risk of developing cervical cancer and a 42% increased risk of dying from the disease. While GII as a composite measure has its limitations, this study suggests that not only poverty reduction but increasing access to preventive health services, and elevating the status of women are essential to reducing cervical cancer disparities.

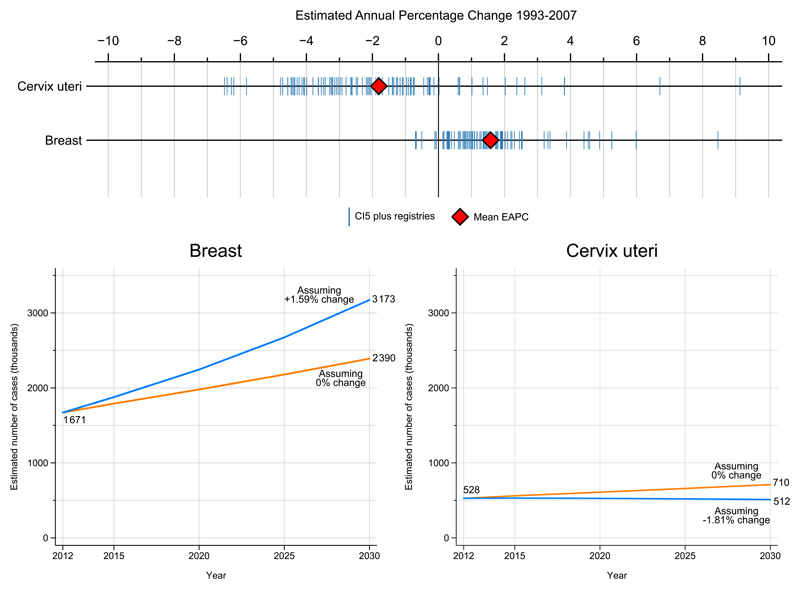

Predicting the future burden

Figure 4 shows the predicted global burden of breast and cervical cancers in 2030. Data available from long-standing high-quality population-based cancer registries from medium, high or very high HDI countries38 suggest that if these average changes continue and become applicable to all countries of the world, the number of women diagnosed with breast cancer will increase to almost 3.2 million per year. Even if incidence rates can be maintained at 2012 levels, a rise to 2.4 million new cases of breast cancer is predicted on the basis of demographic changes alone. For cervical cancer, even if the average decline were observed in all countries globally, almost the same number of women will be diagnosed in 2030 as today, around 510 000 cases. If the cervical incidence rates were to remain unchanged, however, the number of women diagnosed annually is predicted to rise to over 700 000 by 2030.

Figure 4.

Estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) 1993-2007 based on cancer incidence obtained from cancer registries included in several volumes of Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (top). Predicted number of breast and cervical cases (thousands) in 2030 assuming average trends in the EAPC are observed in every country up to 2030 seen in the incidence series, or assuming rates remain unchanged in every country from those estimated in GLOBOCAN in 2012.

The societal impact of women’s cancers

A comparative analysis of epidemiologic data on breast cancer in the United States, Canada, India, China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and Sweden39 showed striking differences in the median age at diagnosis. The peak age at diagnosis was 40-50 years in Asian countries, and 60-70 years for Western countries. Breast cancer has also been shown to occur earlier in life in African countries where such data have been reported, with a median age of approximately 4540–46. It remains unclear to what degree the earlier age at diagnosis is related to variations in the patterns of risk factors and breast cancer subtypes, or simply a reflection of the differences in population structures between countries of low, middle, and high income (for example, the median age of women in The Gambia is 20.5 years, and 41.6 in the UK47).

The median age at diagnosis for invasive cervical cancer depends on the timing of exposure to oncogenic HPV subtypes, and on the latency between exposure, cervical dysplasia and other factors which can affect the likelihood of progressing to invasive disease, as described in the multistage model of carcinogenesis48. Once exposed to an oncogenic HPV subtype, the risk of developing invasive cervical cancer is greatly influenced by immune status, which in turn is related to age at exposure and general immunocompetence. Women who are HIV positive are especially at risk of progression to invasive cervical cancer21, particularly in the absence of screening programmes.

The age-specific profile in high-resource countries exhibits an increase in the incidence rates up until the age of 30-35 years, remaining stable thereafter throughout older ages, most likely as a consequence of the delivery of effective cervical cancer screening programmes. In the United States, the median age at diagnosis of invasive cervical cancer is 47-48 years49, compared with 55-59 years in India50. In one multi-centre study in Limpopo, South Africa, the mean age at diagnosis was 41.3 and 59.1 years for HIV-positive and HIV-negative women, respectively51.

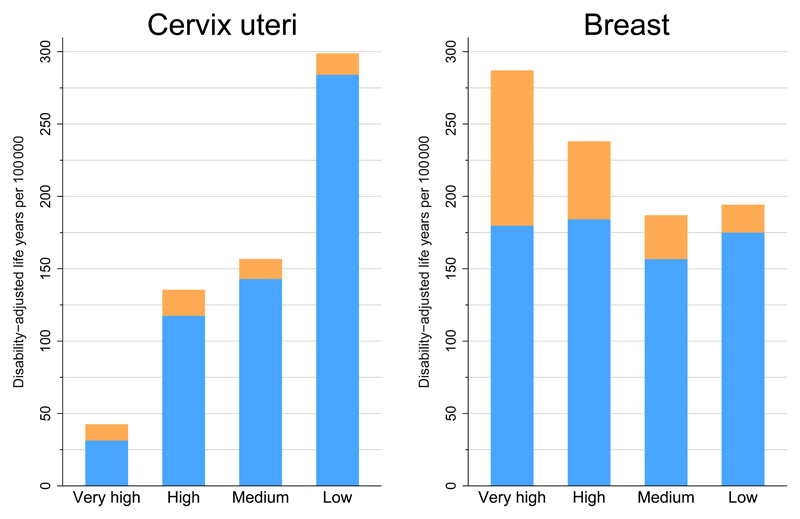

Breast and cervical cancer are key contributors to the overall burden of disease in women. Breast cancer is the leading cause of life years spent with disability (YLD) in 119 countries while cervical cancer is the leading cause in 49 countries2. As a cause of premature death however – as estimated through years of life lost (YLL) – cervical cancer leads breast cancer in 23 countries, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Central and South America. In Figure 5, the DALYs (a composite measure of YLL and YLD) for cervical and breast cancer by four-level HDI are in opposing directions by HDI, while the relative contribution of YLL and YLD to DALYs also differ substantially. Breast cancer is a major contributor to the high overall cancer DALYs in very high HDI countries, with a relatively large contribution of YLD. For cervical cancer, the overall magnitude of DALYs and the large YLL component in low-HDI countries are striking2.

Figure 5.

Age-adjusted DALYs per 100 000 population for cervical and breast cancer in 2008 and four-level Human Development Index. DALYs=disability-adjusted life-years. YLL=years of life lost. YLD=years of life lived with disability. Source: Soerjomataram et al.

The impact of a mother’s death on child survival and wellbeing

Breast and cervical cancer in lower-resource settings disproportionately affect women in the prime of life, resulting in significant economic and societal impact. A mother’s death has complex effects on the children and families she leaves behind. Women are central not only in direct care-giving for their own children, but more broadly in society, playing key roles in the socialization, education and health of children52,53. Women also make relevant, albeit underrecognized, contributions to the health-care labour force. Langer and colleagues have described women’s “crucial roles in the health care of families and communities [as] drivers of the wealth and health of nations”53. The Lancet Commission on Women and Health53in relation to policy for women’s cancers is explored further in the third paper in this Series.

While a close link between maternal mortality and newborn health is established53–55, most studies have focussed on the early weeks and months of a child’s life, highlighting the direct impact of inadequate nutrition from breastfeeding. It is also important to consider the impact of a mother’s death on child survival at other key periods over the life course, including adolescence. Death from untreated and unpalliated cancer is slow, agonizing, and traumatic for patients and families. To our knowledge there are no published studies that specifically address the impact of a woman’s death from cancer on her child’s survival. However, given the rising mortality from cancer in LMIC, and the young ages at which many so women are affected, we suggest that more research is needed to understand the nature and scope of the impact of a mother’s death from cancer on the health and well-being of her children.

Economic impact of women’s cancers

There is overwhelming evidence that investing in women’s health provides significant economic returns53, 56–59. As the economic cost of cancer is estimated at up to 4% of global GDP60, addressing the global burden of women’s cancers should be considered a sound investment by governments11,61,62. The case is compelling given the profound impact of these cancers on premature death and disability, with substantial and long-lasting social, financial and economic consequences for the affected women, their immediate family and their wider community.

Beyond evaluating the cost effectiveness of interventions for breast and cervical cancer control (Series Paper 2), there is a critical need for more evidence on the macroeconomic burden of women’s cancers. Of the 1,676,255 studies on cervical and breast cancer examined by this Series only 3% included an economics component. Furthermore, only one in 10 of these was from a low or middle-income setting. The majority of economic studies identified were based in high-income countries and concerned economic evaluations of the costs and benefits of specific interventions, often under trial conditions, rather than in resource-poor settings or on the wider micro- and macro-economic impacts in resource-poor settings. There is very little information on the economic impact of advocacy or the long-term impact on women with cancer (“survivorship”). If we exclude cost-effectiveness studies focused on specific interventions and concentrate on studies exploring the wider economic impacts of the two cancers, the cervical cancer studies are quite evenly spread across all World Bank income country classifications. However, there were no studies on the wider economic impact of breast cancer specifically from low-income countries.

At the macro-economic level, cancer impacts the national economy and society at large through increased health expenditure, labour and productivity losses, and reduced investment in human and physical capital formation. At the micro-economic level there are profound effects on women, their families, individual firms [companies?] and governments63,64. It is important to note that much of the work undertaken by women is not associated with monetary transactions and is therefore unlikely to be reflected in conventional macro-economic indicators53. Any calculations aiming to assess the economic burden associated with breast and cervical cancer should therefore capture non-income-generating work, such as gathering water and firewood, preparing food, tending to livestock, and caring for children.

If we go beyond the individual impact on women who are diagnosed with, or die from, cancer of the breast or cervix, and include their families, catastrophic expenditure is often more stark65,66. Families are likely to face large medical and non-medical costs, forced to sell assets and accrue debts67–70. This is frequently exacerbated by employment-related complications such as decreased productivity, job loss, dismissal, and reduction of work-related benefits71. A 2015 report of 9513 adults with cancer from eight countries in Southeast Asia66 found that one year after diagnosis, 29% had died, 48% experienced financial catastrophe, and just 23% were alive with no financial catastrophe. Low income was an independent predictor for financial catastrophe, as was education and stage at diagnosis.

Research conducted in Argentina72, at that time a middle-income country, found a marked socio-economic impact on women with cervical cancer, with negative consequences on radiotherapy treatment compliance, despite the fact that 96% of patients reported their radiotherapy was free of charge, either covered by social security, the hospital or other agency. Moreover, study participants reported work interruption (28%), a reduction in hours worked (45%), loss of household income (39%) with nearly one in five families reporting a loss of 50% or more, a reduction in the daily amount of food consumed (37%), delays in paying for essential services such as electricity or telephone (43%), and the sale of property or use of savings (38%).

It is crucial to understand the social, economic, and financial impact of breast and cervical cancer on the health system71–75. How the health system is structured and financed16,76 dictates many of the socio-economic determinants and inequities of access to health services. In addition, the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of interventions for breast and cervical cancer control must be critically evaluated to help inform and prioritise evidence-based, resource-appropriate programs and policy-making. Comprehending the political economy in which decisions on resource allocation are made, both nationally and internationally, is essential if we are to address the macro- and micro-economic impact of breast and cervical cancer77,78. The policy implications are examined in greater depth in paper 3 of this Series (ref).

Conclusions

There are huge global disparities in cancer survival for women[ref]. In lower-resource settings, breast and cervical cancer disproportionately affect women in the prime of life, resulting in significant economic and societal impact. A woman's country, region of residence, income level, socio-economic, ethno-cultural or migration status should no longer be allowed to[?] influence the likelihood of dying from these common cancers. Effective, affordable, cost-effective and life-saving interventions exist.

Several global initiatives are broadening their approach to women’s health along the life-course79,80. The UN Secretary General’s Every Woman Every Child (EWEC) Global Strategy 2.0 aims to accelerate efforts to end preventable maternal, newborn, child and adolescent deaths by 2030. At the 2016 World Economic Forum, [a?] new EWEC high-level advisory group was announced to move the new strategy forward, and to ensure that “every women, child, and adolescent not only survives, but thrives”81. On World Cancer Day, 2016, UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon released a statement that addressed the global inequities in women’s cancers, and called for action to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health concern82.

International efforts have recently led to major improvements in maternal health outcomes: a similar global drive is urgently needed to reduce the impact of breast and cervical cancer, which currently take the lives of some 800 000 women every year. Cancer control for women may be introduced through the new high-priority health and development goals that are beginning to take shape. These topics are explored further in the second and third papers in this Series.

Key Messages.

1. Globally, almost two thirds of women who die from breast cancer and nine in ten women who die from cervical cancer live in low- and middle-income countries. This is a largely preventable tragedy for hundreds of thousands of women and their families each year.

2. Most women who develop breast or cervical cancer in a high-income country will survive; the opposite is true for women in most low and many middle-income countries. Where a woman lives, her socio-economic, ethno-cultural or migration status should no longer mean the difference between life and death from these common cancers, for which cost-effective, life-saving interventions exist.

3. The incidence of breast cancer is expected to increase rapidly with human development. While invasive cervical cancer should be predicted to fall in emerging economies, this is not yet the case in many countries where patterns of sexual behavior are increasing the transmission of oncogenic HPV subtypes, and population-based organized HPV vaccination and cervical screening programs are not yet widely implemented.

4. It is crucial to understand the social, economic, and financial impact of breast and cervical cancers, which take a disproportionate toll on women in LMIC, and in the prime of life. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of interventions for breast and cervical cancer control must be critically evaluated to help inform and prioritise evidence-based, resource-appropriate programs and policy-making.

5. Global efforts, particularly in recent years, have led to significant improvements in maternal health outcomes. Similar efforts are urgently needed to address breast and cervical cancer, which take the lives of three times as many women each year.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria.

Studies were retrieved through systematic searches on the following medical and social sciences electronic databases: EMBASE, Global Health, MEDLINE (OVID), Scopus, Web of Science and Econlit. Variations of search terms related to ‘breast cancer’, ‘cervical cancer’, ‘low income’, ‘middle income’, ‘developing’ countries, the individually named countries of relevance, ‘economic burden’ and ‘economic consequence’, were combined. We searched Google Scholar, scanned the reference lists of the studies retrieved and hand searched the resources and publications of institutional websites. Searches were limited to studies published in English after 1990 containing original quantitative estimates of economic impact.

PANEL 1. Survival disparities in North America and Europe.

Disparities in breast and cervical cancer survival exist within and between high-income countries25, 83–85. Age-adjusted 5-year survival from breast cancer varies by as much as 20% between European Union countries, with lower survival recorded in Eastern European countries85. The international differences in survival have been attributed to differences in stage at diagnosis, access to optimal treatment and national levels of organisation and investment in health care. A European survey on the availability, reimbursement, and other barriers to access reveals important disparities across Europe in access to cancer medicines86. Even in the EU, drug shortages limit access to older, inexpensive medicines that are essential for treatment (with curative or palliative intent), such as tamoxifen for breast cancer, or cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for cervical cancer. In view of their proven efficacy and low cost, these agents, which are included in the recently updated Essential Medicines List6 of the World Health Organization, should be made universally available for all who require them.

It is unclear to what extent differences in tumour biology versus social, economic and other factors play a role in survival disparities within countries. A number of studies have found a greater proportion of triple-negative breast cancers among African-American women87,88, a subtype associated with a poorer survival. However, a recent population-based study in the US87 found persistent differences in 7-year breast cancer-specific survival between African-American and White women, even for stage I disease. The difference in breast cancer-specific survival remained important even after excluding triple negative tumours. This study did not explore access and utilization of cancer services.

African-American women87–95 and women from other minority populations in the US87–91,94–96, the UK97 and Canada98–100 tend to have lower participation in breast and cervical cancer screening programmes and, with some exceptions101, lower cancer survival than the corresponding national averages. Reasons for these disparities are poorly understood and include socioeconomic factors such as economic deprivation, geographic distance to cancer services, lack of health insurance and other social and cultural factors which could affect health-care seeking behaviour87–89,92,100.

In recognition of the magnitude and pervasiveness of these inequities, a number of regional, national and international cancer organizations have established programmes and policies to reduce cancer disparities, not only for breast and cervical cancers but also for cancers more generally, in men, women and children.

Panel 2. Cancer incidence and survival among indigenous women.

Indigenous people in many high-income countries have disproportionally worse health and lower life expectancy than their non-indigenous counterparts. A study led by IARC comparing the scale and profile of cancer incidence among indigenous and non-indigenous populations in USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand has revealed high rates of cervical cancer in almost all jurisdictions, emphasising the need for targeted prevention strategies in these populations102.

Survival from breast and cervical cancer is lower among indigenous women than the national averages in the US, Canada, and Australia 103–107. Vasilevska and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of cervical cancer in indigenous women in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the U.S.103. Of note, they found no difference in the risk for cervical dysplasia or carcinoma in situ but they did find an elevated risk of invasive cervical cancer (pooled RR 1.72) and cervical cancer mortality (pooled RR 3.45). As the indigenous women had a higher risk of cervical cancer morbidity and mortality but no increased risk of early-stage disease, they suggest, “structural, social, or individual barriers to screening, rather than baseline risk factors, are influencing poor health outcomes”.

There remains, however, little information on cancer incidence, survival, and the level of access to cancer services among indigenous populations in LMIC. Recent global and regional reports reviewing cancer among indigenous communities have highlighted the need for more attention to this issue102,108. Efforts to develop joint actions as a partnership between Governments, health professionals and the indigenous communities will be critical in reducing the elevated and avoidable burden of cancer among Indigenous peoples worldwide102.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mathieu Laversanne, IARC, for development of selected figures in this report. We also thank Sabiha Merchant, Women’s College Hospital for her assistance planning and coordinating the Toronto author’s meeting. OG had partial funding from the Canadian Institute for Health Research and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.

Footnotes

Contributions

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent an official position of the organizations they are affiliated with. All authors were responsible for key messages and final draft. OG led the Series.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990– 2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. [accessed online August 8, 2015];Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. ePub June 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Parkin DM, et al. Global burden of cancer in 2008: a systematic analysis of disability-adjusted life-years in 12 world regions. Lancet. 2012 Nov 24;380(9856):1840–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015 Mar 1;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch FX, Robles C, Díaz M, et al. HPV-FASTER: Broadening the scope for prevention of HPV-related cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015 Sep 1; doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan R, Olusegun IA, Anderson BO, et al. Cancer surgery: delivering safe, affordable and timely cancer surgery. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:1193–1224. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. EML. http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/20/applications/cancer/en/

- 7.Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB, et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:1153–1186. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance and WHO. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. [accessed Aug 8, 2015];2014 Jan; http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf.

- 9.United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) http://www.unfpa.org/maternal-health.

- 10.Ginsburg OM, Love RR. Breast cancer: a neglected disease for the majority of affected women worldwide. Breast J. 2011 May 1;17(3):289–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaul FM, Adami HO, Adebamowo C, Arreola-Ornelas H, Berger AJ, Bhadelia A. The global cancer divide: an equity imperative. In: Knaul FM, Gralow R, Atun R, Bhadelia A, editors. Closing the cancer divide: an equity imperative. Harvard Global Equity Initiative; Cambridge, MA: 2012. pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Editorial. Breast cancer in developing countries. Lancet. 2009 Nov 7;374(9701):1567. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61930-9. PubMed PMID: 19897110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitehead M, Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429–45. doi: 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. PubMed PMID: 1644507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008 Nov 8;372(9650):1661–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization; 2013. [Accessed online April 11, 2016]. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. http://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, Gauvreau, Horton S. Chapter 1, Cancer. In: Jamison Dean T, Gelband Hellen, Horton Sue, Jha Prabhat, Laximinarayan Ramanan, Nugent Rachel., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 3rd. United States: World Bank; 2015. Nov 18, [Accessed online Apr 11, 2016]. Coauthor. http://dcp-3.org/cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(11):1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70425-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. The Lancet. 2002;360:187–195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:36–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Muñoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:244–65. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denslow SA, Rositch AF, Firnhaber C, Ting J, Smith JS. Incidence and progression of cervical lesions in women with HIV: a systematic global review. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2014;25(3):163–177. doi: 10.1177/0956462413491735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castellsagué X, Muñoz N. Chapter 3: Cofactors in human papillomavirus carcinogenesis--role of parity, oral contraceptives, and tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;(31):20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, et al. CONCORD Working Group Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995-2009: analysis of individual data for 25,676,887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2) Lancet. 2015;385:977–1010. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sankaranarayanan R, Swaminathan R, Brenne H, et al. Cancer survival in Africa, Asia, and Central America: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:165–73. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bray F. Transitions in human development and the global cancer burden. In: Wild CP, Stewart B, editors. World Cancer Report 2014. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter P. Westernizing’ women’s risks? Breast cancer in lower income countries. NEJM. 2008;358(3):213–216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0708307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United Nations Development Programme. Human development report. [Last accessed 08 June 2015];2013 Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en.

- 28.Writing group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeSantis C, Howlader N, Cronin KA, Jemal A. Breast cancer incidence rates in U.S. women are no Longer declining. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2011;20(5):733–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burstein HJ, Prestrud AA, Seidenfeld J, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(23):3784–3796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collobrative Group (EBCTCG) Peto R, Davies C, Godwin J, et al. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. The Lancet. 2012;379(9814):432–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustafsson L, Ponten J, Bergstrom R, Adami HO. International incidence rates of invasive cervical cancer before cytological screening. Int J Cancer. 1997 Apr 10;71(2):159–65. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<159::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wabinga HR, Nambooze S, Amulen PM, Okello C, Mbus L, Parkin DM. Trends in the incidence of cancer in Kampala, Uganda 1991-2010. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(2):432–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chokunonga E, Borok MZ, Chirenje ZM, Nyakabau AM, Parkin DM. Trends in the incidence of cancer in the black population of Harare, Zimbabwe 1991-2010. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(3):721–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bray F, Lortet-Tieulent J, Znaor A, Brotons M, Poljak M, Arbyn M. Patterns and trends in human papillomavirus-related diseases in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Vaccine. 2013 Dec 31;31(Suppl 7):H32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knaul FM, Bhadelia A, Arreola-Ornelas H, et al. Women's Reproductive Health in Transition: The Overlapping Challenge of Breast and Cervical Cancer. Cancer Control. 2014;11:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh G, Azuine RE, Siahpush M. Global Inequalities in Cervical Cancer Incidence and Mortality are linked to deprivation, low socioeconomic status, and human development. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1:17–30. doi: 10.21106/ijma.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bray F, Ferlay J, Laversanne M, Brewster DH, Mbalawa CG, Kohler B, Piñeros M, Steliarova-Foucher E, Swaminathan R, Antoni S, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents: Inclusion criteria, highlights from Volume X, and the global status of cancer registration. Int J Cancer. 2015 Jul 1; doi: 10.1002/ijc.29670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leong SPL, Shen Z-Z, Liu T-J, et al. Is breast cancer the same disease in Asian and Western women? World J Surgery. 2010;34:2308–2324. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0683-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdulrahman Jnr GO, Rahman GA. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Europe and Africa. J Cancer Epidemiology. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/915610. Article ID 915610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adesunkanmi ARK, Lawal OO, Adelusola KA, Durosimi MA. The severity, outcome and challenges of breast cancer in Nigeria. Breast. 2006;15(3):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rambau PF, Chalya PL, Manyama MM, Jackson KL. Pathological features of Breast Cancer seen in Northwestern Tanzania: A nine years retrospective study. BMC Research Notes. 2011:214–219. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kantelhardt EJ, Zerche1 P, Mathewos A, et al. Breast cancer survival in Ethiopia: A cohort study of 1,070 women. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(3):702–709. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bewtra C. Clinicopathologic features of female breast cancer in Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Cancer Research. 2010;6(3):154–160. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abbass F, Bennis S, Znati K, et al. Epidemiological and biologic profile of breast cancer in Fez-Boulemane, Morocco. Eastern Mediterranean health journal. 2011;17(12):930–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Othieno-Abinya NA, Wanzala P, Omollo R, et al. Comparative study of breast cancer risk factors at Kenyatta National Hospital and the Nairobi Hospital. Journal Africain du Cancer. 2015;7(1):41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 47.CIA. World Factbook. [accessed online Aug 2, 2015]; https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

- 48.Plummer M, Peto J, Franceschi S, on behalf of the International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer Time since first sexual intercourse and the risk of cervical cancer. Int J Ca. 2012;130:2638–2644. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated Cancer Diagnosis by Age. [accessed Aug 8, 2015]; http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/age.htm.

- 50.Sreedevi A, Javed R, Dinesh A. Epidemiology of cervical cancer with special focus on India. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2015;7:405–414. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S50001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Bogaert L-JJ. Age at Diagnosis of Preinvasive and Invasive Cervical Neoplasia in South Africa HIV-Positive Versus HIV-Negative Women. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:363–366. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182094d78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bazile J, Rigodon J, Berman L, Boulanger VM, Maistrellis E, Kausiwa P, Yamin AE. Intergenerational impacts of maternal mortality: qualitative findings from rural Malawi. Reprod Health. 2015;12(Supp 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Langer A, Meleis A, Knaul FM, et al. Women and Health: the key for sustainable development. The Lancet. 2015 Jun 5; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60497-4. ePub accessed online August 2, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braitstein P, Ayaya S, Nyandiko WM, et al. Nutritional Status of Orphaned and Separated Children and Adolescents Living in Community and Institutional Environments in Uasin Gishu County, Kenya. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moucheraud C, Worku A, Molla M, Finlay JE, Leaning J, Yamin AE. Consequences of maternal mortality on infant and child survival: a 25-year longitudinal analysis in Butajira Ethiopia (1987-2011) Reprod Health. 2015;12(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stenberg K, Axelson H, Sheehan P, et al. Study Group for the Global Investment Framework for Women’s Children’s Health Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: a new Global Investment Framework. Lancet. 2014;383:1333–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62231-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.ILO. Global employment trends for women. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013;382:1898–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hausman R, Tyson LD, Zahidi S. The global gender gap report 2012. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, et al. The global economic burden of non-communicable diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beaulieu N, Bloom D, Bloom R, Stein R. Breakaway: the global burden of cancer-challenges and opportunities. Economist Intelligence Unit. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 62.John RM, Ross H. The Global Economic Costs of Cancer. Livestrong and the American Cancer Society; [Google Scholar]

- 63.WHO guide to identifying the economic consequences of disease and injury. WHO; 2009. ISBN 978 92 4 159829 3. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pakseresht S, Ingle GK, Garg S, Singh MM. Expenditure audit of women with breast cancer in a tertiary care hospital of Delhi. Indian Journal of Cancer. 2011;48(4):428–37. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.92263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Woodward M, Kimman M, Jan S, Mejri AA. The economic cost of cancer to patients and their families in Southeast Asia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;10:43. [Google Scholar]

- 66.ACTION Study Group. Kimman M, Jan S, Yip CH, Thabrany H, Peters SA, Bhoo-Pathy N, Woodward M. Catastrophic health expenditure and 12-month mortality associated with cancer in Southeast Asia: results from a longitudinal study in eight countries. BMC Med. 2015;13:190. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0433-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hailu A, Mariam DH. Patient side cost and its predictors for cervical cancer in Ethiopia: A cross sectional hospital based study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(69) doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoang Lan N, Laohasiriwong W, Stewart JF, Tung ND, Coyte PC. Cost of treatment for breast cancer in central Vietnam. Global health action. 2013;6:18872. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.18872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zaidi AA, Ansari TZ, Aziz K. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from patients undergoing cancer care in a tertiary care hospital. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2012;11(60) doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zeeshan Y, Muhammad Y, Ahson M. A Pilot study the socio-economic impact of cancer on patients and their families in a developing country. European Journal of Medical Research. 2010;15:197. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention. Cervical Cancer Prevention Issues in Depth, No. 3. Seattle: ACCP; 2004. The Case for Investing in Cervical Cancer Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arrossi S, Matos E, Zengarini N, Roth B, Sankaranayananan R, Parkin M. The socioeconomic impact of cervical cancer on patients and their families in Argentina, and its influence on radiotherapy compliance. Results from a cross-sectional study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(2):335–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berraho M, Najdi A, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Salamon R, Nejjari C. Direct costs of cervical cancer management in Morocco. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: Apjcp. 2012;13(7):3159–63. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.7.3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boncz I, Endrei D, Agoston I, Kovacs G, Vajda R, Csakvari T, et al. Annual health insurance cost of breast cancer treatment in Hungary. Value in Health. 2014;17(7):A735. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Goldie SJ. Estimating the cost of cervical cancer screening in five developing countries. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2006;4 doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davari M, Yazdanpanah F, Aslani A, Hosseini M, Nazari AR, Mokarian F. The direct medical costs of breast cancer in Iran: Analyzing the patient's level data from a cancer specific hospital in Isfahan. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;4(7):748–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boutayeb S, Boutayeb A, Ahbeddou N, Boutayeb W, Ismail E, Tazi M, et al. Estimation of the cost of treatment by chemotherapy for early breast cancer in Morocco. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2010;8(16) doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gelband H, Sankaranarayanan R, Gaureau C, et al. Costs, affordability and feasibility of an essential package of cancer control interventions in low- and middle-income countries: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition. The Lancet. 2015 Nov 11; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00755-2. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bustreo F, et al. Women's health beyond reproduction: Meeting the challenges. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90:478–478A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.103549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Atun R, Jaffar S, Nishtar S, et al. Improving responsiveness of health systems to non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):690–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy 2.0. [Accessed online Apr 11, 2016]; http://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/en/

- 82.UN Secretary General Statement World Cancer Day. [Accessed online Apr 11, 2016];2016 Feb 4; http://www.un.org/en/events/cancerday/sgmessage.shtml.

- 83.Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377:127–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62231-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Walters S, Benitez-Majano S, Muller P, et al. Is England closing the international gap in cancer survival? BJC. 2015;1-13 doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman M, et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: EUROCARE-5. Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:23–24. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cherny NI, Eniu A, Sullivan R, et al. ESMO European Consortium Study on the availsbility of anti-neoplastic medicines across Europe. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(suppl. 4) iv39 (abstr. 114IN) [Google Scholar]

- 87.Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon P, Sun P, Narod S. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015 Jan 13;313(2):165–173. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tao L, Gomez SL, Keegan THM, Kurian AW, Clarke OA. Breast Cancer Mortality in African-American and Non-Hispanic White Women by Molecular Subtype and Stage at Diagnosis: A Population-Based Study. CEBP. 2015;24(7):1039–1045. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bigby J, Holmes MD. Disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:35–44. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, Rohan T, Aragaki A, Lane D, et al. Ethnicity and breast cancer: factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:439–48. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Newmann SJ, Garner EO. Social inequities along the cervical cancer continuum: a structured review. Cancer Causes Control. 2005 Feb;16(1):63–70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1290-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Newman LA, Griffith KA, Jatoi I, Simon MS, Crowe JP, Colditz GA. Metaanalysis of survival in African American and white American patients with breast cancer: ethnicity compared with socioeconomic status. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1342–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–2501. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maskarinec G, Sen C, Koga K, Conroy SM. Ethnic Differences in Breast Cancer Survival: Status and Determinants. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2011 Nov;7(6):677–687. doi: 10.2217/whe.11.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013 Jul 24;310(4):389–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gomez SL, Clarke CA, Shema SJ, Chang ET, Keegan TH, Glaser SL. Disparities in breast cancer survival among Asian women by ethnicity and immigrant status: a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:861–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.176651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Szczepura A, Price C, Gumber A. Breast and bowel cancer screening uptake patterns over 15 years for U.K. South Asian ethnic minority populations, corrected for differences in socio-demographic characteristics. BMC Pub Health. 2008;8:346. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hanson K, Montgomery P, Bakker D, Conlon M. Factors influencing mammography participation in Canada: an integrative review of the literature. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:65–75. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i5.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lofters AK, Moineddin R, Hwang SW, Glazier RH. Predictors of low cervical cancer screening among immigrant women in Ontario, Canada. BMC Womens Health. 2011;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ginsburg O, Fischer HD, Shah BR, et al. A population-based study of ethnicity and breast cancer stage at diagnosis in Ontario. Current Onc. 2015;22:97–104. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maringe C, Li R, Mangtani L, Coleman MP, Rachet B. Cancer survival differences between South Asians and non-South Asians of England in 1986–2004, accounting for age at diagnosis and deprivation. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:173–181. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Moore S, Antoni S, Colquhoun A, Healy B, Ellison Loschmann L, Garvey G, Bray F. Cancer incidence among indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: a comparative population-based study. Lancet Oncology. Oct 14;:2105. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00232-6. ePub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vasilevska M, Ross SA, Gesink D, Fisman DN. Relative risk of cervical cancer in indigenous women in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Public Health Policy. 2012 May;33(2):148–64. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2012.8. Epub 2012 Mar 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Javid SH, Varghese TK, Morris AM, et al. Guideline-concordance cancer care and survival among American Indian/Alaskan Native patients. Cancer. 2014;120:2183–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Valery PC, Coory M, Stirling J, Green AC. Cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survival in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: a matched cohort study. The Lancet. 2006;367:1842–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shannon GD, Franco OH, Powles J, Leng Y, Pashayan N. Cervical cancer in Indigenous women: The case of Australia Maturitas. 2011 Nov;70(3):234–45. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.07.019. Epub 2011 Sep 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Moore SP, Green AC, Bray F, et al. Survival disparities in Australia: an analysis of patterns of care and comorbidities among indigenous and non-indigenous cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:517. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Moore SP, Forman D, Pineros M, Fernandez SM, de Oliveira Santos M, Bray F. Cancer in indigenous people in Latin America and the Caribbean: a review. Cancer Medicine. 2014;3:70–80. doi: 10.1002/cam4.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]