Abstract

This study examined the effects of e-coaching on the implementation of a functional assessment-based intervention delivered by an early intervention provider in reducing challenging behaviors during home visits. A multiple baseline design across behavior support plan components was used with a provider-child dyad. The e-coaching intervention consisted of weekly training and support delivered via video conferencing software. Results demonstrated a functional relation between e-coaching and early intervention provider implementation of targeted behavior support plan strategies. Further, the child's challenging behaviors decreased over the course of the study. Contributions to the literature, implications for practice, and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: coaching, early intervention, challenging behavior, functional assessment based intervention

Research indicates that children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are more likely to display challenging behaviors than children with other developmental or intellectual disabilities (Dunlap et al., 1994; Hattier, Matson, Belva, & Horovitz; 2011; McClintock, Hall, & Oliver, 2003). While many children who engage in challenging behaviors respond to high quality universal strategies (e.g., structured routines, engaging environment, and skill teaching), some engage in persistent challenging behaviors in spite of high quality programming. Challenging behaviors interfere with learning, can be physically harmful, and put children at risk for later social and academic problems (Kaiser & Rasminsky, 2012; McCabe & Frebe, 2007; Poulou, 2015). Although challenging behaviors are not necessarily a core feature of ASD, ASD symptoms (i.e., delays in social and communication skills) are likely to occasion challenging behaviors (Horner, Carr, Strain, Todd, & Reed, 2002). Challenging behaviors that interfere with effective instruction for young children have been recognized as a serious concern facing early childhood (Dunlap et al., 2006). Furthermore, parents of children witsh ASD cite challenging behaviors among their greatest concerns (Bromley, Hare, Davison, & Emerson, 2004; Doubet & Ostrosky, 2015). Challenging behaviors are a significant source of parental stress and can negatively impact the quality of life for children with ASD and their families (Fox, Vaughn, Wyatte, & Dunlap, 2002; Strain, Schwartz, & Barton, 2011). In fact, research has consistently demonstrated that without timely, targeted, and effective intervention, challenging behaviors in children with ASD can be expected to continue, and often worsen (Dunlap et al., 2006; Frey et al., 2015; Horner et al., 2004).

Social emotional skills and behavioral expectations develop within the context of the family. Thus, numerous authors have documented the importance of addressing social development and problem behaviors in the early years within the context of the home environment during family routines and activities (Brennan, Shaw, Dishion, & Wilson, 2012; Conroy & Brown, 2004; New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003). Consistent with this recommendation, parents of children with ASD report that challenging behaviors were evident as early as toddlerhood (Davis & Carter, 2008). It may be easier and more efficient to address challenging behaviors as soon as they begin to emerge rather than once they become persistent, pervasive across contexts and caregivers, and severe. Given the early onset and relatively long relationship, early intervention (EI) providers working with families with toddlers with disabilities might be uniquely situated to coach parents to use interventions that target challenging behaviors (Fox, Clarke, & Dunlap, 2013).

EI services are a federal grant program funded under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) that assists states in operating a comprehensive program for supporting families of infants and toddlers (from birth through 36 months) with disabilities. During an EI session, challenging behaviors can negatively impact the quality of service delivery and present a significant barrier to participation in learning opportunities. Further, EI providers must have a deep understanding of effective intervention practices to support child learning and effective support practices to encourage parents' use of such practices (Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005).

One example of an intervention that EI providers might be expected to use and coach family members to use is functional assessment-based (FA) intervention for preventing and reducing challenging behaviors. Extensive research has shown that individually tailored FA interventions are an effective approach for reducing challenging behaviors and increasing pro-social behaviors (Dunlap & Fox, 2011; Fettig & Barton, 2014; Fettig, Schultz, & Sreckovic, 2015). The assumption underlying FA interventions is that the challenging behavior is serving a specific function for the individual (e.g., gaining attention, escaping demands). For children with ASD, who have difficulty communicating, challenging behaviors (e.g., tantrums) can be more effective and efficient than acceptable communicative forms (e.g., pointing or talking; Frea & Hampton, 1999; Matson & Nebel-Schwalm, 2007). Studies that compared FA interventions to non-function based interventions have consistently noted distinct advantages in the effectiveness of FA interventions (Ingram, Lewis-Palmer, & Sugai, 2005). Also, research has demonstrated that FA interventions can be implemented in natural settings (Conroy, Asmus, Sellers & Ladwig, 2005; Duda, Clarke, Fox, & Dunlap, 2008; Fettig & Barton, 2014; Fettig & Ostrosky, 2011).

When working with families who have toddlers with disabilities and severe, persistent challenging behaviors, EI providers need a deep understanding of FA interventions to effectively implement and coach parents to effectively implement FA interventions to prevent and reduce challenging behaviors. However, a documented and significant gap remains between research and practice in EI (Dunst & Trivette, 2009; Hebbeler, Spiker, & Kahn, 2012; Metz & Bartley, 2012; Odom, 2009) and many EI providers are not fluent in FA interventions, which limits their ability to support parents in preventing and addressing child challenging behaviors. While FA-based interventions have proven to be effective and feasible for parents to implement, research continues to document that coaching and ongoing support are needed to ensure high fidelity use and to yield desirable child outcomes (Barton & Lissman, 2015; Fettig & Barton, 2014; Fettig et al., 2015; Lucyshyn et al., 2015). Equipping EI providers with the knowledge and skills to implement FA interventions enables them to effectively maximize learning for children during home visits and coach parents in addressing and preventing challenging behaviors throughout their daily routines (Division for Early Childhood, 2014).

Likewise, research has shown that families received relatively small amounts of face-to-face services (Hebbeler et al., 2007) and the amounts of EI services families receive are fewer than recommended by research, not all eligible children and families are being served (Hebbeler, Spiker & Kahn, 2012). Furthermore, supporting families in their homes can be time, resource, and effort intensive, and simply is not accessible in all communities particularly when EI providers must travel long distances to reach families (Johnson, Brown, Chang, Nelson, & Mrazek, 2011; Kelso, Fiechtl, Olsen, & Rule, 2009). As the field continues to explore efficient, efficacious, and cost-effective ways to support EI providers (Salisbury & Cushing, 2013), the idea of providing these supports through technology as a feasible mode of delivery should be considered. Utilizing available technologies (e.g., Skype©, FaceTime™) to provide e-coaching to support EI providers during in-home service delivery might be more efficient than traditional face-to-face coaching or mentoring. Further, EI agencies might have specialists on staff who can provide this level of behavioral expertise through e-coaching, but who do not see families as often as the EI providers.

Recent studies using technology to deliver coaching have shown promise with early childhood practitioners (Barton, Pribble, & Chen, 2013; Hemmeter, Snyder, Kinder, & Artman, 2011; Vismara, Young, Stahmer, Griffith, & Rogers, 2009) and EI providers (Marturana & Woods, 2012). However, no study to date has examined the use of technology in supporting EI providers' use of FA interventions. The purpose of this study is to extend the literature on e-coaching with EI providers to support their use of FA interventions to address challenging behaviors in a child with ASD. The two research questions guiding this study were: (1) Is there a functional relation between e-coaching and increased levels of use of FA interventions by the EI provider?, and (2) What are the impacts of the intervention on the child challenging behaviors during home visits?

Method

Participants

One EI provider (Lusa) and one child with ASD (Bella) participated in this study. Participants were recruited through a federally funded project that focused on addressing health disparities in the ASD diagnosis, service utilization, and school engagement among young children living in poverty in an urban city in the Northeast.

EI provider

Lusa was Bella's EI provider. She had abachelor's degree in early childhood education and had worked as a developmental specialist and EI case coordinator for over 15 years. Lusa identified as Latina and of Hispanic descent and was fluent in both English and Spanish. She started working with Bella shortly after Bella turned two years old when she was referred for EI. According to Lusa, she and Bella's parents were from the same cultural and language background and had a good relationship. Because Lusa spoke fluent Spanish, the parents' primary language, the home visits were primarily conducted in Spanish. Lusa expressed her concerns to the research team regarding Bella's challenging behaviors during home visits and sought help and support to address these behaviors. Lusa encouraged the parents to participate in this research study as the primary adult participants in receiving coaching and implementing the FA interventions. However, due to parents' reluctance to participate, Lusa decided to be the primary adult participant as a means of gaining their buy-in, addressing Bella's challenging behaviors, and demonstrating the efficacy of the FA interventions. Lusa stated that she felt Bella's parents reluctance to participate was due to the language differences between them and the research staff and other personal issues currently impacting the family.

Child

Bella was a 30-month old child of Hispanic descent and lived with her parents and two siblings. Both of Bella's parents identified themselves as Latino and Hispanic and spoke Spanish as their primary language; only one parent had conversational English ability. Bella's speech and occupational therapy services were delivered each week by English speaking therapists, but her primary EI provider, Lusa, spoke Spanish with her. Bella had been diagnosed with ASD at 28 months and showed significant language and communication delays. For the four months prior to the diagnosis, Bella received one hour per week of developmental therapy and speech therapy due to her significant language delays. Bella's parents reported that she exhibited challenging behaviors frequently in the form of screaming, spitting, hitting, climbing on furniture, property destruction, and self-injurious behaviors. The EI provider reported observing similar behaviors during weekly home visits. Prior to the current intervention, she used uncoordinated gestures and grunts to communicate her wants and needs. Also, Bella frequently engaged in challenging behaviors (tantrums, noncompliance, verbal aggression, property destruction, and physical aggression towards others or self), which were confirmed through direct observation by the researchers.

Experimental Design and Analysis

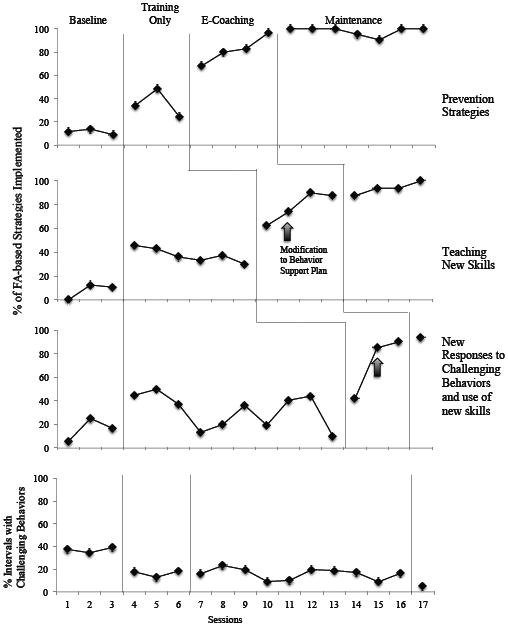

A multiple-baseline design across the three FA intervention strategies (i.e., prevention strategies, teaching new skills, provider's new responses to child's challenging behaviors and use of new skills) was used to examine the relation between e-coaching and Lusa's use of the FA intervention during the home visit sessions (Gast & Ledford, 2014). Thus, there were three intra-subject opportunities to demonstrate an effect. In multiple baseline designs the intervention is applied to the first tier to demonstrate stable data patterns. The intervention commences in the second tier with stable data patterns once data stabilizes in the first tier. The intervention is applied to the final tier in the same manner. Experimental control is established when changes in data patterns coincide with the introduction of the intervention and there are no subsequent changes in untreated tiers. Efforts were made to implement a condition change when Lusa demonstrated stable rates of target behaviors; however, baselines were not extended for lengthy periods due to the practical urgency in supporting the provider to resolve the self-injurious and other challenging behaviors. Consistent with single case research design methodology, visual analysis was used to conduct formative and summative assessment of the data patterns (Kratochwill et al., 2013). Level, trend, variability, overlap, immediacy, and consistency of the data patterns were analyzed (Gast & Ledford, 2014).

Procedures

Setting

The initial intervention training session with Lusa was conducted in her office. The subsequent coaching sessions were delivered in an e-coaching format, via Facetime™, a video conferencing software, at a time and location convenient for Lusa on a weekly basis following each home visit observation. The observations were conducted during weekly EI home visits in the child's home. While at least one of the parents were present at every visit, the researchers focused on coaching Lusa in reducing Bella's challenging behaviors during the home visit session rather than working directly with parents at the parents' preference.

Functional behavior assessment (FBA)

Prior to baseline, the first author conducted a FBA using a functional assessment interview and multiple direct observations (O'Neil et al., 1997). The Functional Assessment Interview Form-Young Child and Home Observation Card (Center on the Social Emotional Foundations for Early Learning; CSEFEL, 2013) were used to gather this information. This systematic process guides the behavior support plan team in understanding the challenging behavior and the environmental factors or events that might trigger (i.e., antecedents) and maintain or follow (i.e., consequences) the challenging behavior to identify the purpose or function of the challenging behavior. Interviews were conducted with Lusa and Bella's parents and direct observations were conducted during weekly home visits prior to the start of the study. The researchers worked closely with Lusa and the parents in analyzing the interview and observation data to determine the function(s) of Bella's challenging behaviors. Because of the intensity of the challenging behaviors, concerns shared by Lusa and the parents, and clear data patterns discerned from the FBA process, functional analyses were not conducted to prevent prolonging the introduction of intervention strategies. Furthermore, research has shown that direct and indirect assessment procedures associated with FBA can be just as effective in identifying the function of challenging behavior as a functional analysis (Alter, Conroy, Mancil, & Haydon, 2008). The functional behavior assessment provided clear indications of functions of Bella's challenging behaviors and revealed that her behaviors often resulted in her avoiding non-preferred tasks and obtaining attention from adults. For example, when she was asked to clean up, she engaged in self-injurious behavior such as banging her head against the wall or hitting her head with her closed fist, which was likely to result in her escaping from the clean up task. Bella also frequently placed toys and objects in her mouth, which was likely to result in attention from Lusa or her parents.

Baseline (A)

Lusa and Bella's interactions were observed for 3 weeks during baseline. The length of each observation was approximately one hour. During baseline sessions, the first author observed the provider-child dyad during their weekly home visits. Lusa was instructed to interact with Bella and to respond to Bella's challenging behaviors as she normally would during the home visit. No instructions regarding challenging behaviors were offered. The baseline observations captured Lusa's use of all three components of FA intervention strategies

Collaborative behavior support plan development

Following baseline and immediately before the training-only condition, the first author met with Lusa for a 2-hour training on FA intervention and collaboratively created a behavior support plan. The first author had a Ph.D. in early childhood special education and has worked with parents and teachers for over 10 years in creating and supporting the implementation of individualized behavior support plans to address challenging behaviors. This two-hour training session consisted of the following content: (a) the importance of social emotional development in young children; (b) possible functions of challenging behaviors; (c) the findings of the functional behavior assessment information and baseline data; and (d) possible strategies to address the challenging behaviors.

The training protocol, baseline data, and drafted behavior support plan were reviewed by the research team which included the first author who served as the trainer and coach for this project, a BCBA-D faculty with extensive knowledge in conducting FBA and creating behavior support plans for children with challenging behaviors, and two clinical psychology professionals who have extensive experience with young children with ASD.

A subsequent 1-hour training session was scheduled with the first author, Lusa, and Bella's parents and the drafted behavior support plan was then shared with Bella's parents to ensure that both parents' ideas and thoughts were accurately represented in the plan. Lusa served as an interpreter during this process. The researchers then used live modeling to demonstrate implementation of the behavior support plan strategies and answered the questions Lusa and the parents had regarding implementation. Throughout the training, Lusa and Bella's parents were encouraged to share their perspectives regarding characteristics of Bella's behaviors that might affect the implementation of the behavior support plan and strategies they tried before the study. Together the researchers, Lusa, and Bella's parents brainstormed potentially helpful strategies based on Bella's strengths and the family's philosophies and values. In addition, the researchers shared videos of others implementing FA interventions with young children. Through this iterative process, strategies were added and modified to ensure contextual fit. For example, the researchers suggested the use of a visual timer to support Belle in transitioning between activities during home visits. However, Lusa and Bella's parents expressed concerns because the timer could serve as a distractor for Bella. Instead, Lusa suggested the use of a counting system.

By the end of the training session, Lusa, Bella's parents, and researchers had collaboratively created a behavior support plan (see Table 1) with descriptions of target behaviors, hypothesized functions of the behaviors, and strategies to prevent and reduce Bella's challenging behaviors during the home visit. The behavior support plan included three primary components: (1) prevention strategies, (2) teaching new skills, and (3) provider's new responses to child's challenging behaviors and new skills used (Lucyshyn, Kayser, Irvin, & Blumberg, 2002; Fettig, Schultz, & Ostrosky, 2013). Prevention strategies are carefully selected antecedent-based strategies that are used to prevent the likelihood of challenging behavior (Powell, Dunlap, & Fox, 2006). For example, prevention strategies for Bella included conducting sessions in quiet areas of the family's apartment to reduce distractions, providing clear expectations at the beginning of each session (e.g. we are going to play games, we are going to sit.), and providing transitioning warnings between activities (Fettig et al., 2013). Several new skills to teach Bella that were functionally equivalent to her challenging behaviors also were identified. In collaboration with Lusa and Bella's parents, three communicative requests were identified as goals for Bella: help, all done/break, and my turn/more. Bella was also taught to wait by counting from 1-10. Lusa was taught to use verbal modeling and prompting with visuals and sign language to teach and reinforce Bella's use of these skills. In addition, Lusa provided at least one opportunity during each activity for Bella to practice each of these new skills. Finally, Lusa was coached to respond to Bella's challenging behavior in a manner that communicated that the challenging behavior will not work. For example, when Bella engaged in challenging behaviors to request for a different toy, Lusa reminded her to sign or say “All Done”. When Bella reached to grab toys during transition, Lusa prompted Bella to count from 1-10 to signal that she needed to wait. Further, Lusa was instructed to respond to Bella's appropriate communicate with contingent, explicit praise and access to requested items. The research team created visual support materials needed (i.e., first-then visual chart, activity choices visual cue cards, “stop” cue card, “break” cue card, “my turn” cue card) to implement the behavior support plan. These materials were presented to Lusa and Bella's parents to be used during home visits and throughout home routines.

Table 1. Behavior Support Plan for Bella.

| Components | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Prevention Strategies |

|

| New Skills to Teach Bella |

|

| Lusa's New Responses to Bella's Challenging Behaviors and Bella's Use of New Skills |

|

Training Only (B)

At the start of this condition, the researchers gave Lusa a copy of the behavior support plan and a self-monitoring behavior support plan checklist to record her use of the planned strategies; while not required, they strongly encouraged Lusa to use the checklist to monitor her own implementation. Lusa did not receive further instruction regarding the strategies during this training. The training only condition continued until the EI provider demonstrated a stable rate of responding for at least one category of target strategies.

Coaching (C)

Prior to the start of the coaching session, the research team created a coaching protocol, and the first and second author reviewed the protocol and walked through a coaching scenario. The first author who had extensive experience coaching parents and early education professionals in addressing challenging behaviors served as the coach for this study. During this condition Lusa received coaching on the first component of target strategies (i.e., Prevention Strategies) from the first author once per week following the home visit sessions. Coaching sessions were delivered via a video conferencing application (Facetime™). Each e-coaching session lasted between 30-45 minutes, and most of these sessions were conducted one- to two- business days following the weekly home visit. The focus of the e-coaching was to discuss the use of strategies and behavior changes observed in the previous home visit. The coach reviewed the videotapes for the week prior to the coaching sessions and followed a 10-step coaching implementation checklist created for this study (see Table 2) to guide the coaching sessions. The coaching sessions typically started with Lusa reviewing the self-monitoring behavior support plan checklist to reflect on strategies used and challenges faced during the home visit. Next, the coach provided performance-based feedback by commenting on strategies that were implemented and pointing out how the strategies implemented had reduced Bella's challenging behaviors. The coach also provided specific examples of how Lusa could implement the strategies differently or how missed strategies could have been implemented. The coach shared video clips from the previous sessions and showed graphs of changes in the observed frequency of FA strategies and child behaviors over time to illustrate strategies that were implemented well, missed opportunities, and other relevant behavior changes observed. Each coaching session ended with an opportunity for Lusa to ask questions. It also is important to note that throughout the coaching process, the coach continue to collaborate with Lusa and Bella's parents regarding their perspectives of what strategies were effective and feasible and which were difficult to implement. Based on this feedback, minor modifications to the behavior support plan were made to ensure a contextual fit. E-coaching continued until Lusa was consistently implementing the set target strategies at stable, high levels.

Table 2. Coaching Implementation Checklist.

| Steps | Coaching Strategy |

|---|---|

| 1 | Coach ensures video-conferencing software allows clear communication for both parties. |

| 2 | Coach facilitates discussion on the use of self-monitoring checklist (which lists steps to implement behavior support plan strategies) and EI provider provides a summary of overall implementation and observed outcomes. |

| 3 | EI provider reflects on which strategies worked well and observed outcomes. |

| 4 | EI provider reflects on which strategies were challenging to implement or was not effective in addressing behaviors. |

| 5 | Coach provides overall impression of the home visit session and the implementation of the behavior support plan. |

| 6 | Coach provides positive feedback on used strategies and outcomes observed. |

| 7 | Coach provides examples of strategies within the behavior support plan that were not implemented or misused; Coach provides examples of non-used and misused strategies and model suggested implementation strategies. |

| 8 | Coach and EI provider discuss ways to improve implementation for the next home visit session. |

| 9 | Coach provides videos of home visit when necessary to aid coaching discussion. |

| 10 | Coach provides the EI provider an opportunity to ask questions and request for additional resources. |

When Lusa implemented the first set of targeted strategies (i.e., Prevention strategies) at a stable, high level, the coaching sessions commenced with the second set of target strategies (i.e., Teaching New Skills). The focus of the coaching session shifted to the third component of target strategies (i.e., New Responses to Challenging Behaviors) when Lusa consistently implemented Teaching New Skills strategies at stable, high levels.

Maintenance (D)

This condition occurred immediately following the coaching condition. During this condition, coaching was withdrawn when Lusa consistently implemented the component of targeted strategies at a stable, high level. Lusa was instructed to continue to implement the component of strategies independently during this condition.

Target Behaviors

Provider target behaviors

Lusa's implementation of the behavior support plan strategies was the primary dependent variable in this study. The behavior support plan strategies included prevention strategies, teaching new skills to Bella, and new responses to Bella's challenging behaviors. A checklist was created to include all FA intervention strategies for each of three types of strategies, which was used during each session. Data were collected on the presence or absence of each of these strategies during the home visit. The prevention strategies included two antecedent based strategies (i.e., reduce distraction and provide expectations) to be implemented at the beginning of each home visit and four strategies to be implemented within each of the activities with the session. Lusa created opportunities to teach each of the four new skills that were identified as essential communication skills for Bella. For example, Lusa would present Bella with the bubbles and wait for Bella to request for help to open the bottle. There were three new strategies to guide Lusa in responding to Bella's challenging behaviors. Lusa's new responses to Bella's challenging behaviors and Bella's use of new skills were measured as present or absent contingent to Bella's behaviors. For example, when Bella engaged in a challenging behavior and Lusa used one of the strategies listed in the behavior support plan, the use of strategy would be counted. When Bella used a new skill and Lusa did not provide contingent, specific praise, a new response was not counted.

The number of strategies used in each observation was dependent on the number of activities in which Bella engaged. An activity was defined as the presentation of one toy/object of engagement (e.g. bubbles, puzzles, nesting cups) to completion of clean up of the toy/object of engagement and placed out of sight. For example, if Lusa presented 3 activities to Bella, she would have opportunity to implement each of these two components of strategies three times. For Lusa's new responses to Bella's behavior, the presence and absence of strategies would depend on the number of challenging behaviors and new skills Bella used in each of the activities. These data were then summarized as the percentage of strategies implemented during each activity in each home visit session and were calculated by dividing the number of strategies implemented by the number of total strategies possible and multiplying the quotient by 100.

Child challenging behaviors

The secondary dependent variable in this study was Bella's challenging behaviors during the observed home visit sessions. Challenging behaviors were defined as any occurrence of inappropriate behavior including tantrums, noncompliance, verbal aggression, property destruction, and physical aggression towards others or self. Tantrums were defined as high intensity screaming and crying combined with physical resistance, disruptive or destructive behavior that interrupted the continuation of targeted routines, or physical aggression. Noncompliance was defined as any incident when a directive was given to the child and either no action was taken by the child within 5 seconds of the adult directive or the child protested, which included as grunting, turning her back to the interventionist, walking away from the intervention session, and/or loudly declaring her nonparticipation by screaming “No.” Verbal aggression was defined as high pitched or loud utterances, or angry grunts with volume louder than typical conversation. Property destruction was defined as any incident in which the child destroyed or attempted to destroy property, including throwing, punching, hitting, kicking, breaking, pushing, and yanking an object. Physical aggression towards others included hitting, kicking, biting, spitting or grabbing objects from another person. Challenging behaviors were coded using 15-second interval partial interval recording system, which provided an estimated duration of challenging behaviors for each home visit. The estimated percentage of time the child exhibited challenging behaviors was calculated by dividing number of intervals with challenging behaviors by the total number of intervals and then multiplying by 100. Challenging behavior was coded for 30-minutes and commenced after the first 15 minutes of the observation session.

Data Collection

All observation, training, and coaching sessions were videotaped by a personnel on the research team. Following a 2-hour training on the behavioral coding system by the lead author, a graduate research assistant who was an early childhood education major and an experienced special education teacher completed all coding. The graduate research assistant was presented with behavior definitions and the behavior support plan. Video segments of the provider-child interaction during a non-study home visit were used for this training. During the training, provider and child behaviors were independently coded in 15-minute increments by both the first author and the graduate student to determine interobserver agreement (IOA). The first author and the student engaged in a discussion regarding any coding discrepancies. Training continued until IOA was above 80% for three consecutive coding segments.

Interobserver Agreement

The graduate research assistant and the first author independently coded thirty-five percent of the videos across all conditions. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements. These calculations were conducted for total agreement and agreement on occurrences. The mean IOA for provider implementation of behavior support plan was 98.5% (range = 93.7-100%). The mean IOA for child challenging behavior coding was 96.3% (range = 92.6-100%).

Procedural Fidelity

Procedural fidelity was assessed to determine if the training and coaching sessions were conducted as intended. A training protocol checklist was developed (see Table 2) to record implementation of the training procedures and content. This checklist was used to determine whether or not the training protocols were followed during each training session. Videotapes of the training sessions were reviewed by another graduate research assistant. Implementation fidelity was 100% for the training prior to coaching, which indicated that the training was conducted as intended. A coaching protocol checklist also was developed to record the first author's implementation of coaching strategies during intervention and the absence of coaching during baseline and training. This checklist consisted of the 10-step coaching process that the first author followed during each e-coaching session. This graduate research assistant completed this checklist based on the videotapes for all coaching sessions. Procedural fidelity for coaching was 100% for all sessions assessed, indicating that all coaching procedures were implemented as intended during coaching and were not implemented during baseline or training.

Results

Visual analysis of graphed data was used to interpret the effects of the training-only and e-coaching conditions on Lusa's use of targeted strategies. Specifically, level, trend, variability, and consistency of the data were analyzed within conditions and level, trend, variability, overlap, immediacy, and consistency of the data were analyzed between conditions (Gast & Ledford, 2014; Kratochwill et al., 2013). Figure 1 illustrates the percent of target strategies implemented by Lusa and Bella's challenging behaviors are presented in the final tier in Figure 1.

Figure 1. EI Provider's use of FA-based strategies and Bella's challenging behavior.

EI Provider's Implementation of FA-Based Strategies

Lusa implemented a stable and low level of prevention strategies during baseline (see Figure 1). Following the training session, an immediate change in level of implementation was observed with moderate variability. When e-coaching was provided, data showed an immediate upward trend and no overlap with previous conditions. Lusa reached close to 100% implementation by the end of the condition, which maintained at a high level with little variability after e-coaching was withdrawn. Similarly, Lusa used few strategies to teach Bella during the baseline. Occasionally, she requested that Bella say “My turn” during a turn-taking activity. She had an immediate increase in level during the training only condition prior to coaching. While there was no overlap with baseline, there was a slight downward trend. Once e-coaching was implemented, an immediate increase in level with an upward trend occurred, which had limited variability and no overlap with previous conditions. During the second tier, a modification was made to teach Bella to sign “All done” instead of asking her to present an “All done” visual card. When this modification was made, the data continued to increase in level with an upward trend. A similar data pattern was observed after e-coaching was withdrawn, indicating that Lusa maintained use of strategies to teach Bella new skills with e-coaching. In the third tier (New Responses), Lusa used few FA based responses to Bella's challenging behaviors during baseline. However, Lusa infrequently reinforced Bella's use of appropriate skills (e.g. waiting, or asking for a turn). While an immediate change was observed during the training only condition, the data were variable and several data points overlapped with baseline. After the first e-coaching session, the data remained at a level similar to the training phase. During the second e-coaching session of this tier, a modification was made to the FA intervention strategies to have Lusa clearly establish that toys were for playing and not for putting in Bella's mouth. An immediate increase in level with an upward trend occurred, which had limited variability and no overlap with previous conditions. Overall, experimental control was established because the target behaviors increased corresponding to the introduction of the e-coaching intervention at three different points in time, which is consistent with multiple baseline design logic (Gast & Ledford, 2014).

Child Behaviors

Bella engaged in moderate levels of challenging behaviors during baseline. An immediate decrease in the level occurred during the training-only with no overlap with previous conditions. Her challenging behaviors remained at a low level during the e-coaching with some variability and significant overlap with previous conditions, which also remained low and similar pattern as training-only and e-coaching phase after e-coaching was withdrawn.

Social Validity

An interview was conducted by research personnel after the completion of the study to assess the social validity of this intervention from Lusa. Lusa shared that the e-coaching intervention was efficient and very effective in supporting her in addressing Bella's challenging behaviors during home visits. She reported that Bella's home visits were more productive once she was able to manage the challenging behaviors. She spent more time engaging her in meaningful play and less time “controlling” her behavior. She also shared that the intervention allowed her to reflect on the home visits she conducts with each of her clients to fit the needs of each one of them she works with. Social validity data was not collected from Bella's parents.

Discussion

We investigated the effects of e-coaching on an EI provider's implementation of FA intervention strategies and child challenging behaviors. Overall, the results indicated that the EI provider implemented some target strategies after the training. When e-coaching was provided, she implemented the strategies at higher levels and maintained the use of these strategies after e-coaching was withdrawn. We observed a decrease in the child's challenging behaviors as her EI provider implemented the targeted strategies at consistent and high levels.

The results extend current research and support the use of e-coaching in helping EI provider use FA intervention strategies in home settings. This study demonstrated that prior to e-coaching, the EI provider used few FA intervention strategies to reduce child challenging behaviors. When e-coaching was provided, the EI provider implemented the strategies at higher levels, which maintained after coaching was withdrawn. Second, as the EI provider increased her use of the FA-based strategies, the rate of the child's challenging behaviors decreased and maintained throughout the study. This finding is consistent with earlier evidence that coaching and support is necessary to yield desirable outcomes (Fukkink, 2008) and that early childhood practitioners can implement FA interventions (Conroy et al., 2005).

The EI provider implemented some FA intervention strategies during the training condition, though not with high fidelity. This is consistent with previous research, which found that professionals generally benefit from didactic training, but additional supports are needed to implement the strategies to fidelity and positively impact child outcomes (Artman-Meeker & Hemmeter, 2013; Barton, Pribble, Chen, Pomes, & Park, 2013; Fox, Hemmeter, Snyder, Binder, & Clarke, 2011). In the current study, the EI provider was trained to use FA intervention strategies that worked for the challenging behaviors observed during home visits. Previous research shows that parents have implemented FA interventions with coaching (Fettig, et al. 2015; Duda, et al., 2008; Brookman-Frazee, Stahmer, Baker-Ericzen & Tsai, 2006). However, no research has examined EI providers’ use of FA intervention strategies, which might be essential for supporting parent's use of FA interventions.

Interestingly, the child's challenging behaviors decreased following the training but did not decrease further during e-coaching condition. Previous research has shown significant decreases in challenging behaviors only when FA-based strategies were implemented consistently and at fidelity (Fettig et al., 2015; Fox et al., 2013). This could be attributed to the nature of the child's disability, the complexity of her challenging behaviors, or the limitations with our measurement system (i.e., partial interval systems might over or under estimate behaviors with varying durations; Lane & Ledford, 2014). Further examinations of such behavior change patterns are warranted. Importantly, her challenging behaviors decreased such that engagement and instructional time increased. The EI provider did not have to redirect or respond to challenging behavior as often as during baseline sessions, which, although only anecdotally noted, allowed for more opportunities for positive interactions and more instructional time. Moreover, the child developed adaptive communication strategies (e.g., request for help, requesting for a turn) from the implementation of the behavior support plan.

Perhaps, more importantly, this study sought to identify an efficient, yet effective, approach to supporting an EI provider in reaching fidelity. As noted by previous research, the effectiveness of intervention is highly associated with the fidelity in which it is implemented (Fixsen et al., 2005). Despite evidence that intervention fidelity is key to intervention effectiveness, it has often not been reported in the FA intervention literature (Duda et al., 2008; Harding et al., 2009; Schultz, Schmidt, & Stichter, 2011). The current study specifically assessed the EI provider's use of FA-based strategies and she reached nearly 100% fidelity during the coaching condition. The implementation of the strategies maintained for the first two sets of strategies; however, there is only one datum point from the third set, which limits interpretations. This is consistent with research that has suggested training outcomes are increased when the trainee received individual coaching to support the implementation of the strategies in the naturalistic setting (Fettig & Barton, 2014; Snyder et al., 2012). Although there is evidence that coaching might support EI providers use of recommended practices, future research is needed to examine efficient ways to do so. Additional studies are needed to examine effective coaching practices and delivery modalities suitable to the implementation of FA-based interventions.

Significant health disparities exist in access to early diagnosis and treatment for ASD (Chiri & Warfield, 2011; Durkin et al., 2010); these disparities fall along lines of race, income, and English learner status. As with other treatments for children with ASD, access to interventions that address challenging behaviors is crucial. E-coaching provides EI providers an opportunity to receive efficient coaching. This mode of coaching delivery extends access of support to providers with limited resources for support. For example, EI providers in rural areas often find direct support to be costly and time consuming. E-coaching yielded desirable outcomes for the EI provider and the child in the current study.

The findings from this study are particularly significant because challenging behaviors for children with ASD often act as barriers to effective intervention and instruction, interfere with engagement, and impact family quality of life. The current study presented evidence that suggested EI providers can implement FA-based strategies with support. This is important, because EI providers are well situated to coach families to implement these strategies.

Limitations and Future Research

While the study employed a rigorous single case research methodology and a functional relation was demonstrated between the intervention and the implementation of strategies, the data should be interpreted with caution because the study only included one interventionist-child dyad. Additional inter-subject replications are needed to advance the evidence for e-coaching with EI providers. Further, while the results suggest e-coaching is an effective modality to support EI providers, this study did not examine the effects of strategies used within the coaching. Future research should focus on the intricate pairing of specific coaching practices with e-coaching delivery. For example, systematic examination of which coaching strategy is most impactful or least effective when deliver via online modalities is warranted.

One of the key limitations of this research study is the lack of data to examine the EI provider's use of newly learned strategies to support parents in addressing challenging behaviors in the daily home routines. While EI provider's competence in addressing challenging behaviors during a home visit enhances the effectiveness of service delivery, a key goal of equipping EI providers with these skills is for them to serve as resources and supports for parents who also experience similar challenging behaviors during their daily routines. Future studies should examine the extent to which EI providers can transfer their knowledge of FA intervention to families and its impact on child challenging behaviors in daily routines.

A second key limitation is the lack of data regarding Bella's use of replacement skills or time engaged during the sessions. Although noted anecdotally, there was an important shift in the quality of the sessions when Bella began using the communication skills Lusa taught her. Her engagement in the session increased, which led to more positive interactions between Bella and Lusa, and Bella and her parents. Further, Bella's increased engagement allowed Lusa to provide more learning opportunities. Previous research has documented the relation between FA interventions and increased used of functional skills by young children (Dunlap, Ester, Langhans, & Fox, 2006). However, future studies should examine increased engagement and subsequent increases in positive interactions and learning opportunities as a result of FA interventions.

Additionally, the study did not closely assess the EI provider's ability to generalize learned strategies to other settings or with other children and families. Future research in areas of implementation and intervention fidelity and identifying effective coaching practices for FA-based intervention that are cost effective are needed. Likewise, future research examining effective strategies for ensuring EI providers have the knowledge and skills to use FA interventions is essential. This content should be included in both preservice programs and inservice professional development. Finally, as the field moves forth in identifying evidence-based practices, its crucial to understand factors that support generalization of strategies.

Conclusion

Challenging behaviors are a significant source of stress for families of children with ASD, early educators, and service providers. In this study, we investigated an innovative practice to support EI providers in addressing challenging behaviors during home visits. E-coaching delivered via video conferencing was a promising way of providing supports to practitioners in the field in implementing FA-based strategies. Future research should investigate the intricate pairings of coaching practices delivered via e-coaching and how this support delivery method might influence the generalization and long term maintenance of strategies.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under Grant No. R40MC26195 Maternal Child Health Research. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Contributor Information

Angel Fettig, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Erin E. Barton, Vanderbilt University.

Alice Carter, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Abbey Eisenhower, University of Massachusetts Boston.

References

- Alter PJ, Conroy MA, Mancil GR, Haydon T. A comparison of functional behavior assessment methodologies with young children: Descriptive methods and functional analysis. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2008;17:200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Artman-Meeker KM, Hemmeter ML. Effects of training and feedback on teachers' use of classroom preventive practices. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2013;33:112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Barton EE, Lissman DC. Group parent training combined with follow-up coaching for parents of children with developmental delays. Infants and Young Children. 2015;28:220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Barton EE, Pribble L, Chen CI. The use of e-mail to deliver performance-ased feedback to early childhood practitioners. Journal of Early Intervention. 2013;35:270–297. [Google Scholar]

- Barton EE, Pribble L, Chen C, Pomes M, Park YA. Coaching pre-service teachers to embed prompting procedures in inclusive preschool classrooms. Teacher Education in Special Education. 2013;36:330–349. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan LM, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson M. Longitudinal predictors of school-age academic achievement: Unique contributions of toddler-age aggression, oppositionality, inattention, and hyperactivity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1289–1300. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9639-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley J, Hare DJ, Davison K, Emerson E. Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. Autism. 2004;8:409–423. doi: 10.1177/1362361304047224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer A, Baker-Ericzen MJ, Tsai K. Parenting interventions for children with autism spectrum and disruptive behavior disorders: Opportunities for cross fertilization. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:181–200. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning. Functional Assessment Interview Form – Young Children. 2013 Retrieved from http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/modules-archive/module3a/4.pdf.

- Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning. Home Observation Cards. 2013 Retrieved from http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/modules-archive/module3a/3.pdf.

- Chiri G, Warfield ME. Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;16:1081–1091. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy MA, Asmus JM, Sellers JA, Ladwig CN. The use of an antecedent-based intervention to decrease stereotypic behavior in a general education alassroom: A case study. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy MA, Brown WH. Early identification, prevention, and early intervention with young children at risk for emotional or behavioral disorders: Issues, trends, and a call for action. Behavioral Disorders. 2004;29:224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Davis NO, Carter AS. Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:1278–1291. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda MA, Clarke S, Fox L, Dunlap G. Implementation of positive behavior support with a sibling set in a home environment. Journal of Early Intervention. 2008;30:213–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, dePerczel M, Clarke S, Wilson D, Wright S, White R, Gomez A. Choice making to promote adaptive behavior for students with emotional and behavioral challenges. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:505–518. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Fox L. Function-based interventions for children with challenging behaviors. Journal of Early Intervention. 2011;33:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Strain PS, Fox L, Carta JJ, Conroy M, Smith B, et al. Sowell C. Prevention and intervention with young children's challenging behavior: A summary and perspectives regarding current knowledge. Behavioral Disorders. 2006;32:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Trivette CM. Research evidence to inform and evaluate early childhood intervention practices. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2009;29:40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin MS, Maenner MJ, Meaney FJ, Levy SE, DiGuiseppi C, Nicholas JS, et al. Schieve LA. Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: evidence from a US cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettig A, Barton EE. Functional assessment based parent intervention to reduce children's challenging behaviors: A literature review. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2014;34:49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fettig A, Ostrosky MM. Collaborating with parents in reducing children's challenging behaviors: Linking functional assessment to intervention. Child Development Research. 2011;2011:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fettig A, Schultz T, Ostrosky MM. Collaborating with parents in using effective strategies to reduce children's challenging behaviors. Young Exceptional Children. 2013;16:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fettig A, Schultz TR, Sreckovic MA. Effects of Coaching on the Implementation of Functional Assessment–Based Parent Intervention in Reducing Challenging Behaviors. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2015 Advance online publication. doi:10.98300714564164. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI Publication No 231) Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fox L, Clarke S, Dunlap G. Helping families address challenging behavior: Using positive behavior support in early intervention. Young Exceptional Children Monograph Series No 15. 2013:59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fox L, Hemmeter ML, Snyder P, Perez Binder D, Clarke S. Coaching early childhood special educators to implement a comprehensive model for promoting children's social competence. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2011;31:178–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fox L, Vaughn BJ, Wyatte ML, Dunlap G. “We can't expect other people to understand”: Family perspectives on problem behavior. Exceptional Children. 2002;68:437–450. [Google Scholar]

- Frea WD, Hepburn SL. Teaching parents of children with autism to perform functional assessments to plan interventions for extremely disruptive behaviors. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 1999;1:112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fukkink RG. Video feedback in widescreen: A meta-analysis of family programs. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:904–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gast DL, Ledford JR. Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harding JW, Wacker DP, Berg WK, Lee JF, Dolezal D. Conducting functional communication training in home settings: A case study and recommendations for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009;2:21–33. doi: 10.1007/BF03391734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattier MA, Matson JL, Belva BC, Horovitz M. The occurrence of challenging behaviours in children with autism spectrum disorders and atypical development. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2011;14:221–229. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2011.573836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbeler K, Spiker D, Kahn L. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act's Early Childhood Programs: Powerful Vision and Pesky Details. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2012;31:199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmeter ML, Snyder P, Kinder K, Artman K. Impact of e-mail performance feedback on preschool teachers' use of descriptive praise. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2011;26:96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Carr EG, Strain PS, Todd AW, Reed HK. Problem behavior interventions for young children with autism: A research synthesis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 2002;32:423–446. doi: 10.1023/a:1020593922901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Dunlap G, Koegel RL, Carr EG, Sailor W, Anderson J, Albin RW, O'Neill RE. Toward a technology of “nonaversive” behavior support. In: Bambara L, Dunlap G, Schwartz E, editors. Positive behavior support: Critical articles on improving practice for individuals with severe disabilities. PRO-ED and TASH; 2004. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram K, Lewis-Palmer T, Sugai G. Function-based intervention planning: Comparing the effectiveness of FBA indicated and contra-indicated intervention plans. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2005;7:224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Brown S, Chang C, Nelson D, Mrazek S. The cost of serving infants and toddlers under Part C. Infants & Young Children. 2011;24(1):101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser B, Rasminsky J. Third Edition. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2012. Challenging behavior in young children: Understanding, preventing, and responding effectively. [Google Scholar]

- Kelso GL, Fiechtl BJ, Olsen ST, Rule S. The feasibility of virtual home visits to provide early intervention: A pilot study. Infants & Young Children. 2009;22(4):332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kratchowill TR, Hitchcock JH, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, Shadish WR. Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial and Special Education. 2013;34:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn JM, Fosset B, Bakeman R, Cheremshynski C, Miller L, Lohrman S, et al. Irvin LK. Transforming parent-child interaction in family routines: Longitudinal analysis with families of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0154-2. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn JM, Kayser AT, Irvin LK, Blumberg ER. Functional assessment and positive behavior support at home with families. In: Lucyshyn JM, Dunlap G, Albin R, editors. Families and positive behavior support: Addressing problem behavior in family contexts. Baltimore: Brookes; 2002. pp. 97–132. [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Nebel-Schwalm M. Assessing challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2007;28:567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marturana ER, Woods JJ. Technology-supported performance-based feedback for early intervention home visiting. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2012;32:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe LA, Frede EC. Challenging behaviors and the role of preschool education. National Institute for Early Education Research Preschool Policy Brief, 16. 2007 Dec; Retrieved from http://nieer.org/resources/policybriefs/16.pdf.

- McClintock K, Hall S, Oliver C. Risk markers associated with challenging behaviours in people with intellectual disabilities: A meta‐analytic study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:405–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz A, Bartley L. Active Implementation Frameworks for program success: How to use implementation science to improve outcomes for children. Zero to Three Journal. 2012;32:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Final report (Pub No SMA-03-3832) Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. [Google Scholar]

- Odom SL. The tie that binds: Evidence-based practice, implementation science and outcomes for children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2009;29:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill RE, Horner RH, Albin RW, Sprague JR, Storey K, Newton JS. Functional assessment and program development for problem behavior: A practical handbook. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Powell D, Dunlap G, Fox L. Prevention and interventions for the challenging behaviors of toddlers and preschoolers. Infants & Young Children. 2006;19:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury CL, Cushing LS. Comparison of triadic and provider-led intervention practices in early intervention home visits. Infants & Young Children. 2013;26:28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz TR, Schmidt CT, Stichter JP. A review of parent education programs for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2011;26:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder P, Hemmeter ML, Artman K, Kinder K, Pasia C, McLaughlin T. Characterizing key features of the early childhood professional development literature. Infants and Young Children. 2012;25:188–212. [Google Scholar]

- Strain PS, Schwartz IS, Barton EE. Providing Interventions for Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders What We Still Need to Accomplish. Journal of Early Intervention. 2011;33:321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Division for Early Childhood. DEC recommended practices in early intervention/early childhood special education 2014. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.dec-sped.org/recommendedpractices.

- Vismara LA, Young GS, Stahmer AC, Griffith EM, Rogers SJ. Dissemination of evidence-based practice: can we train therapists from a distance? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:1636–1651. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0796-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]