Abstract

Background.

The demand for training in complex general surgical oncology (CGSO) fellowships currently exceeds the number of positions offered; however, there are scarce data defining the applicant pool or characteristics associated with successful matriculation. Our study aimed to describe the applicant population and to determine factors associated with acceptance into the fellowship.

Study Design.

Data were extracted from the Electronic Residency Application System for applicants in 2015 and 2016 and stratified based on matriculation status. Applicant demographics, including medical education, residency, and research achievements, were analyzed. Academic productivity was quantified using the number of peer-reviewed publications as well as the journal with the highest impact factor in which an applicant’s work was published.

Results.

Data were gathered on a total of 283 applicants, of which 105 matriculated. The overall population was primarily male (63.2%), Caucasian (40.6%), educated at a U.S. allopathic medical school (53.4%), and trained at a university-based General Surgery residency (55.5%). Education at a U.S. allopathic school (OR = 5.63, p < 0.0001), university-based classification of the applicant’s surgical residency (OR = 4.20, p < 0.0001), and a residency affiliation with a CGSO fellowship (OR = 2.61, p = 0.004) or National Cancer Institute designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (OR = 3.16, p < 0.001) were found to be associated with matriculation. Matriculants published a higher number of manuscripts than nonmatriculants (median of 10 vs. 4.5, p < 0.0001) and more frequently achieved publication in journals with higher impact factors (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions.

This study represents the first objective description of the CGSO fellowship applicant pool. Applicants’ medical school, residency, and research data points correlated with successful matriculation.

Upon completion of a general surgery residency, surgeons can enter practice or apply for further education in one of several designated fellowship programs. In recent years, the rate at which general surgery residents have elected to pursue fellowship training has increased markedly.1 It has been reported that nearly 80% of residents now pursue some form of additional training.2,3 Among the choices for graduating residents is further training in complex general surgical oncology.

As interest and need for specialized cancer care has increased, the surgical community has established standardized fellowship training in surgical oncology. As defined by the American Board of Surgery (ABS), a surgical oncologist has specific knowledge and skills related to the diagnosis, multidisciplinary treatment, and rehabilitation required by patients with cancer, especially those with complex presentations or requiring complex surgical procedures, or with rare or unusual cancers.4 In 2011, a new board certification in Complex General Surgical Oncology (CGSO) was announced.4,5 There are currently 30 fellowships training programs (25 in the United States, 5 in Canada) recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), and their graduates are eligible to sit for the designated written and oral board examinations.6

Despite significant interest among residents and medical students, there are currently no objective data accurately describing the population of applicants to CGSO fellowship or any factors associated with successful matriculation.1 Previous studies have sought to define factors associated with matriculation to hepatopancreaticobiliary (HPB), pediatric, and endocrine surgery fellowships using survey studies or through review of single-institution data.7–10 However, surveys or single institution reviews do not capture the entire applicant pool for any given specialty and therefore are subject to inherent biases. To provide a comprehensive and objective view of application to CGSO fellowship training, we obtained data on all applicants from the Electronic Residency Application System (ERAS). Our purpose was to define the demographics and characteristics of the overall CGSO applicant pool and to determine factors predictive of successful matriculation.

METHODS

Data Acquisition

Approval was granted for the release of deidentified data based on an existing data sharing contract between the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the National Institutes of Health. All data originated from ERAS for the 2015 and 2016 application cycles, which correspond to matriculation dates August 2016 and August 2017, respectively. As a means to preserve applicant privacy, all data were collected from ERAS directly by data operations specialists at the AAMC and deidentified prior to acquisition by our group.

CGSO fellowship programs are approved by the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) as well as the ACGME and, for the application years listed, consisted of 22 American programs and 3 Canadian programs.6,11 All approved programs require ERAS as a means of accepting applications for fellowship positions and, as such, all applicants to these programs in 2015 and 2016 were captured in this analysis. A total of 283 applicants were identified and were then stratified based on candidates who applied and later matriculated versus those that applied and did not matriculate. To determine if an ERAS applicant matriculated to a CGSO fellowship, applicant ID numbers in GME Track of ERAS were cross-referenced with the rosters of the specified fellowship programs. Seven individuals applied in both ERAS years 2015 and 2016. For these applicants, only demographic and qualification data from the 2016 ERAS application were included in analysis.

Applicant demographics, medical school and residency characteristics, and publication data were retrieved by the AAMC data specialists and provided to our group for further analysis. Baseline information on applicants’ residency programs and their affiliations was gathered by means of the American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database (FREIDA) and matched to their ACGME Identification number. Residency programs are officially classified in FREIDA as university-based, community-based, or community-based/ university-affiliated. Residencies falling outside of these classifications are military programs, American Osteopathic Association programs, and international residencies, and are denoted in a combined group labeled “Other.”

Our group then sought to examine if an applicant’s origin from a residency that had a relationship with a CGSO fellowship program or with a National Cancer Institute designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCICCC) influenced matriculation. Institutional and hospital affiliation of an applicant’s home residency program was determined based on FREIDA. A residency program was considered linked with a CGSO fellowship institution only in instances in which a PGY3–5 resident rotated with the fellowship for more than 4 weeks and functioned as a chief resident on a service. This was verified by examining a residency program’s officially listed curriculum and/or a direct telephone contact to the residency office. Additionally, a residency was considered linked with an NCI-CCC if a resident of any training level rotated in a surgical oncology capacity at that institution. It should be noted that not all CGSO fellowships are based at an NCI-CCC and vice versa.

Finally, published manuscripts authored by the applicants were quantified, and the name of each journal in which an applicant published was recorded. A publication was considered any authorship of a scientific or clinical manuscript. Articles with the status of “under review” or “accepted but not yet published” were excluded. It should be noted that although applicants sign a legal agreement attesting to the validity and honesty of their application, this section is self-reported by applicants and not verified independently. To gain insight into applicants’ publication records, data were gathered on the Impact Factor (IF) of the journals in which an applicant’s manuscripts were published. Journal IFs were obtained from Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Reports for the year 2016 as calculated by Clarivate Analytics based on citations. A small portion of the journals in which applicants had published were too recent to have had impact factor calculated. Journals were ranked into academic tiers based on their IFs, with low tier journals defined by IF < 2.5, mid-tier as IF 2.5–9.9, and high tier journals possessing an IF ≥ 10. The highest tier in which an applicant achieved publication was recorded as that applicant’s impact tier. Individuals that did not have any publications listed were classified as Tier 0.

Statistical Analysis

Applicant characteristics were described and stratified according to matriculation status. Differences in characteristics were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test and with odds ratios to demonstrate the association of potentially important factors on matriculation. Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was applied to determine the significance of trends in publication in increasing impact factor journals on matriculation status. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Applicant Characteristics

There were 283 applicants included in the ERAS CGSO applicant pool for 2015 and 2016. The average applicant age was 33.6 years. The overall population was primarily male (63.2%), Caucasian (40.6%), and educated at a U.S. allopathic medical school (53.4%; Table 1). Of those educated at an allopathic school, 25.8% indicated membership in the AOA. More than half of the applicants completed general surgery residency at a university-affiliated program (55.5%), and most did not train at an NCICCC or CGSO fellowship affiliated program (Table 1). The median number of publications authored per applicant was 7 (mean 9.1, range 0–66), and the median impact factor of journals where work was published was 3.3 (mean 4.3, range 0.0–47.8). The average number of ERAS applications submitted to CGSO fellowships per individual was 14.9 in 2015 and 17.6 in 2016.12

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of all applicants to CGSO fellowships in 2015 and 2016

| Characteristic (n = 283) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 33.6 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 179 (63) |

| Female | 104 (37) |

| Race | |

| White | 115 (41) |

| Black | 9 (3) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 39 (14) |

| Hispanic | 9 (3) |

| Othera | 111 (39) |

| Citizenship | |

| U.S. | 182 (64) |

| International | 101 (36) |

| Medical education | |

| U.S. allopathic | 151 (53) |

| U.S. osteopathic | 94 (33) |

| International | 38 (13) |

| AOA membershipb | 39 (14) |

| General surgery residency attributes | |

| University affiliated | 157 (56) |

| Community-based university-affiliated | 14 (7) |

| Community-based | 31 (15) |

| Otherc | 81 (29) |

| CGSO fellowship-affiliated residency | 44 (21) |

| NCI-CCC-affiliated residency | 101 (49) |

Other races includes American Indian and non-U.S. residents

AOA status includes U.S. Allopathic graduates only and does not represent percentage of entire population

Other classification of residency included American Osteopathic Association Surgical residencies, Military-based residencies, or international residencies

Factors Differentiating Matriculants and Nonmatriculants

Of the 283 applicants included in this analysis, 105 (37.1%) matriculated to a CGSO fellowship, whereas 178 (62.9%) did not. Seven applicants applied in both 2015 and 2016, of which one individual eventually matriculated. Characteristics of matriculants and nonmatriculants are detailed in Table 2. Compared with nonmatriculants, a higher percentage of matriculants attended U.S. allopathic medical schools (78.1 vs. 38.8%, p < 0.0001), were members of AOA (21.0 vs. 9.6%, p = 0.012), and were trained at university-based surgical residencies (76.2 vs. 43.3%, p < 0.0001). Also at a higher rate, matriculants trained at residencies that were CGSO fellowship-affiliated (23.8 vs. 10.7%, p = 0.004) and/or NCI-CCC affiliated (52.4 vs. 25.8%, p < 0.0001; Table 2). Odds ratio analysis of these factors is shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference between matriculated and nonmatriculated applicants with regard to median Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) score (31 vs. 30, p = NS; data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of applicants to CGSO fellowships stratified by matriculation status

| Characteristic | Matriculants | Nonmatriculants |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 105 | 178 |

| Medical school | ||

| U.S.-allopathic public | 36 (34%) | 36 (20%) |

| U.S.-allopathic private | 46 (44%) | 33 (19%) |

| U.S.-osteopathic | 14 (13%) | 80 (45%) |

| International | 9 (9%) | 29 (16%) |

| Residency | ||

| University-based | 80 (76%) | 77 (43%) |

| Community-based | 7 (7%) | 24 (14%) |

| Community-based university-affiliated | 6 (6%) | 8 (5%) |

| Othera | 12 (11%) | 69 (39%) |

| CGSO fellowship affiliated residency | 25 (24%) | 19 (11%) |

| NCI-CCC affiliated residency | 55 (52%) | 46 (26%) |

Other classification of residency included American Osteopathic Association Surgical residencies, Military-based residencies, or international residencies

TABLE 3.

Applicant characteristics associated with matriculation

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. allopathic schoola | 5.63 | 3.24–9.78 | < 0.0001 |

| AOA statusb | 2.51 | 1.26–4.99 | 0.012 |

| University-based residencyc | 4.20 | 2.45–7.19 | < 0.0001 |

| Residency with CGSO fellowship affiliation | 2.61 | 1.36–5.03 | 0.004 |

| Residency with NCI-CCC affiliation | 3.16 | 1.90–5.25 | < 0.0001 |

U.S. allopathic school status includes both private and public schools and comparison is done against all applicants from non-U.S. allopathic schools (osteopathic, international, etc.)

AOA (Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society) membership status is compared to no AOA membership (including both MDs that did not achieve AOA as well as international or DO applicants who were not eligible)

University-based residency is compared to all other residency subtypes, including community-based, osteopathic, and international

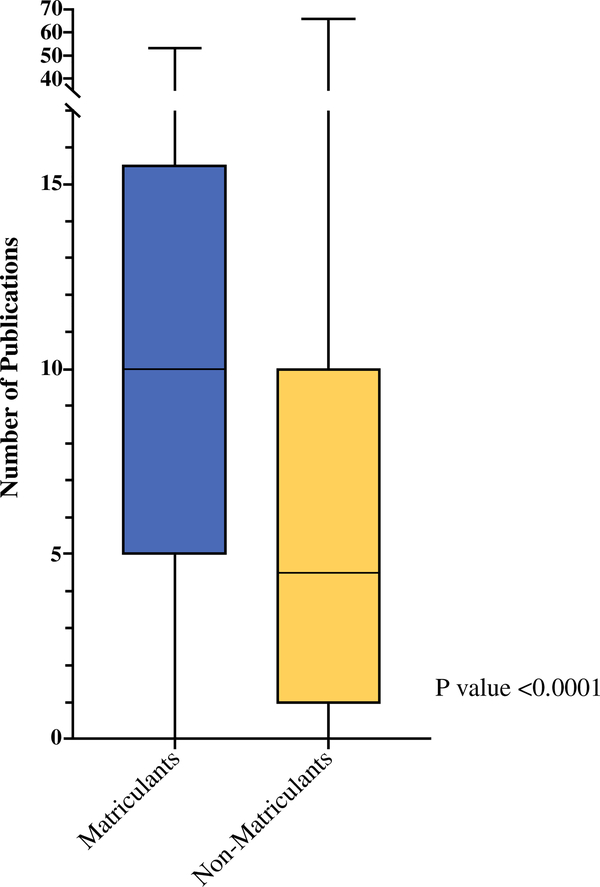

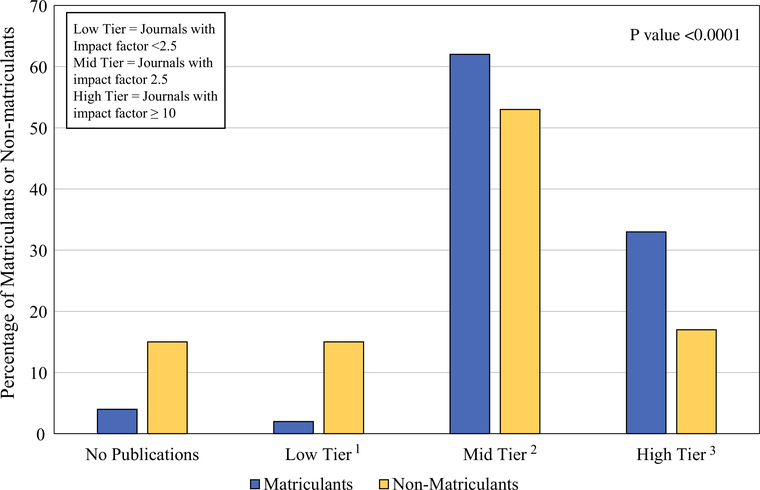

The median number of publications reported by applicants who matriculated was significantly higher than that of nonmatriculated applicants (10.0 vs. 4.5, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1) (mean 11.7 ± 9.7 vs. 7.5 ± 9.6). The impact factors of the journals where applicants’ work was published, when classified using an impact factor-based tiering system, also differed significantly between the groups. Matriculated applicants demonstrated an increasing percentage of publications relative to non-matriculated applicants as impact-factor tier increased from 1 to 3 (Fig. 2). Using the Cochran-Armitage test, there was a significant trend for matriculants to achieve publication in increasingly higher impact factor journals compared to nonmatriculants (p < 0.0001). Of note, there was no significant difference between matriculated and nonmatriculated applicants with regard to number of published book chapters, academic presentations, work experiences, or volunteer experiences.

FIG. 1.

Quantity of published scientific manuscripts per applicant stratified by matriculation status. Box and Whisker plot showing distribution of the quantity of publications per individual applicant, stratified by matriculation status. Boxes represent lower quartile, median, and upper quartile while whiskers represent range. Difference between matriculants and nonmatriculants was significant with p < 0.0001 as determined by two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test

FIG. 2.

Achievement of publication in highest impact factor journal according to matriculation status. Applicants were classified according to matriculation status and displayed as percentage of matriculants/nonmatriculants within their group. Individuals were then classified by tier based on the journal with the highest impact factor in which work was published. Using the Cochran–Armitage test, there was a significant trend for matriculants to achieve publication in higher impact factor journals compared with nonmatriculants (p < 0.0001). 1 = low tier = journals with impact factor < 2.5. 2 = mid tier = journals with impact factor of 2.5–9.9. 3 = high tier = journals with impact factor ≥ 10

DISCUSSION

The current demand for positions in CGSO fellowship training programs greatly exceeds the number of positions offered, such that most applicants will go unmatched. Despite this burgeoning interest among residents, little, if any, objective data existed about the CGSO applicant pool or specifically about characteristics that may be associated with successful matriculation. We obtained and analyzed source data on all applicants for the first 2 years that applications to the fellowship were required to be submitted via ERAS (application cycles 2015 and 2016). In doing so, we have accurately described the quantifiable metrics of the applicants, including those predictive of matriculation. While this study provides important insight for the aspiring surgical oncologist, it must be noted that a multitude of non-quantifiable factors influence a given applicant’s acceptance, many of which were not evaluated herein. Nonetheless, our analysis offers a first-look at objective metrics including those related to medical education, residency training, and research accomplishments.

Applicants that attended an allopathic medical school in the United States or trained at a university-based surgical residency were more likely to achieve matriculation at a CGSO fellowship. Both factors have been historically valued in the surgical community and likely show a trend in self-selection of applicants: individuals might be likely to choose education at an allopathic school or university based residency because of the perception of academic prestige.13 It should be noted though that approximately one of five matriculants were educated at an osteopathic or international medical school and that almost a quarter were from community based or “Other” classification of residencies. In other words, absolute prerequisites for medical education and general surgery training appear not to exist as successful candidates come from a variety of academic backgrounds. AOA membership also was found to be associated with matriculation, a similar finding for studies examining this factor in applicants to general surgery residencies.14 However, MCAT score, number of academic presentations, work experience, and volunteer experience were not associated with matriculation. While these factors are valued by medical schools in their application process, we suspect that they lose value in distinguishing candidates that have similar credentials as they advance through surgical training.

A residency affiliation with a CGSO fellowship or an NCI-CCC was also associated positively with matriculation. It is likely that these affiliations foster relationships between residents and experts in the surgical oncology field. Residents may have been mentored towards surgical oncology from an earlier time point, had more opportunities to pursue oncology research, and/or had letters of recommendation that carried relatively higher weight being from academic leaders in the field. It is possible that individuals who were motivated to pursue a career in surgical oncology chose to go to these residencies precisely because of their NCI-CCC or CGSO fellowship affiliations.

Not surprisingly, academic achievements appeared to have significant association with successful matriculation. A 2014 study examining 323 general surgery residency graduates showed that 54% of residents authored a publication during their time in residency, and the majority of those residents with authorship had fewer than four publications.15 Our study population of matriculants exhibited exceptional academic productivity compared with this. Awareness of the competitive nature combined with the expectation of academic productivity of CGSO matriculants likely contributed to publication records described in our study.

Not only was volume of publications associated with matriculation but quality was as well. Matriculants were found to achieve publication in a high impact factor journal at a significantly higher rate than nonmatriculants. This was again unsurprising but illustrative of the value of research excellence in applying to CGSO fellowship. While it is an impossible task to objectively evaluate the quality of every publication each applicant submitted, we used impact factor of the publishing journal as a surrogate. Attaining publication in a “high” impact journal is a formidable task that often requires substantial research time. Accordingly, less than a quarter of the total applicant population achieved at least one publication in a journal with an IF > 10. Based on the 2016 Clarivate Analytics Impact Factor calculations, journals specifically focused in the field of Surgery all had IF < 10. Thus, publication in the highest tier of our study was likely synonymous with research work in basic science or in broad clinical studies.

This study has several limitations that must be considered when reviewing our results. First, our study is neither a comprehensive evaluation nor a road map to successful matriculation. Many factors are considered when evaluating an applicant for acceptance to a fellowship program that we were unable to examine. Quality of letters of recommendation and interview performance are prime examples of nonquantifiable data that are not captured by ERAS. In addition, given concern over applicant privacy, we lacked access to a potentially useful metric, American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination (ABSITE) scores. Second, individualized applicant data was deidentified and aggregated by AAMC data specialists prior to acquisition by our group, and, as such, our analysis could not examine raw individual data. This limited the ability of our study to perform more sophisticated statistical analyses. Data deidentification also resulted in an inability to discern whether an applicant was a first author on a publication versus coauthorship of any form. Next, most data that we analyzed were self-reported by applicants themselves, which carries a potential risk of misrepresentation of an applicant’s work. Applicants, nevertheless, sign a legal statement to attest to the validity and truthfulness of their application. Regardless, by examination of ERAS, our report represents an objective observation of applications submitted to CGSO fellowship programs and represents the qualities that program directors view when making judgements on whether to grant an interview.

CONCLUSIONS

We believe that our analysis, despite some important limitations, provides valuable insight into the population of CGSO fellowship applicants and matriculants. Applicants’ medical school, residency, and individual research accomplishments were associated with successful matriculation and provide insights into potential criteria that program directors evaluate. Our analysis of applicants, including those characteristics linked with successful matriculation to CGSO Fellowship training programs, should serve in part to guide aspiring medical students and general surgery residents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors give special acknowledgement to Dr. Marie Caulfield and Dr. Hershel Alexander for their invaluable work at the Association of American Medical Colleges, for their expert data collection and analysis, and for their extremely helpful collaboration with the NCI Surgical Oncology Research Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ellis MC, Dhungel B, Weerasinghe R, Vetto JT, Deveney K.Trends in research time, fellowship training, and practice patterns among general surgery graduates. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(4):309–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borman KR, Vick LR, Biester TW, Mitchell ME. Changingdemographics of residents choosing fellowships: long-term data from the American Board of Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(5):782–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedell ML, VanderMeer TJ, Cheatham ML, Fuhrman GM, Schenarts PJ, Mellinger JD, Morris JB. Perceptions of graduating general surgery chief residents: are they confident in their training? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(4):695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The American Board of Surgery-Specialty of Complex GeneralSurgical Oncology Defined, Training and Certification. http://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?aboutsurgoncdefined. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

- 5.Berman RS, Weigel RJ. Training and certification of the surgicaloncologist. Chin Clin Oncol. 2014;3(4):45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Society of Surgical Oncology-Fellowship Training Programs.http://www.surgonc.org/training-fellows/fellows-education/surgical-oncology/program-list. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

- 7.Baker EH, Dowden JE, Cochran AR, Iannitti DA, Kimchi ET,Staveley-O’Carroll KF, Jeyarajah DR. Qualities and characteristics of successfully matched North American HPB surgery fellowship candidates. HPB. 2016;18(5):479–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser JD, Aguayo P, St Peter S, et al. Analysis of the pediatricsurgery match: factors predicting outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27(11):1239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little DC, Yoder SM, Grikscheit TC, Jackson CC, Fuchs JR,McCrudden KW, Holcomb GW. Cost considerations and applicant characteristics for the pediatric surgery match. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(1):69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulaylat AN, Kenning EM, Chesnut CH, James BC, Schubart JR,Saunders BD. The profile of successful applicants for endocrine surgery fellowships: results of a national survey. Am J Surg. 2014;208(4):685–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Residency Match Program-Specialty Match ProgramResults-2015 and 2016. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Program-Results-2014-2018.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

- 12.Association of American Medical Colleges. Historical SpecialtySpecific Data. Complex Surgical Oncology. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

- 13.Rinard JR, Mahabir RC. Successfully matching into surgicalspecialties: an analysis of national resident matching program data. J Graduate Med Educ. 2010;2(3):316–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stain SC, Hiatt JR, Ata A, et al. Characteristics of highly rankedapplicants to general surgery residency programs. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(5):413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merani S, Switzer N, Kayssi A, Blitz M, Ahmed N, Shapiro AM.Research productivity of residents and surgeons with formal research training. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):865–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]