Abstract

Background:

HIV+ donor organs can now be transplanted into HIV+ recipients (HIV D+/R+) following the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act. Implementation of the HOPE Act requires transplant center awareness and support of HIV D+/R+ transplants.

Methods:

To assess center-level barriers to implementation, we surveyed 209 transplant centers on knowledge, attitudes, and planned HIV D+/R+ protocols.

Results:

Responding centers (n=114; 56%) represented all UNOS regions. Fifty centers (93 organ programs) planned HIV D+/R+ protocols (kidney n=48, liver n=34, pancreas n=8, heart n=2, lung=1), primarily in the eastern US (28/50). Most (91.2%) were aware that HIV D+/R+ transplantation is legal; 21.4% were unaware of research restrictions. Respondents generally agreed with HOPE research criteria except the required experience with ≥5 HIV+ transplants by organ type. Centers planning HIV D+/R+ protocols had higher transplant volume, HIV+ recipient volume, increased infectious-risk donor utilization, and local HIV prevalence (p<0.01). Centers not planning HIV D+/R+ protocols were more likely to believe their HIV+ candidates would not accept HIV+ donor organs (p<0.001). Most centers (83.2%) supported HIV+ living donation.

Conclusions:

Although many programs plan HIV D+/R+ transplantation, center-level barriers remain including geographic clustering of kidney/liver programs and concerns about HIV+ candidate willingness to accept HIV+ donor organs.

Keywords: HIV, HOPE Act, HIV-infected donors

INTRODUCTION

HIV-infected (HIV+) transplant candidates have increased risk of waitlist mortality and decreased access to transplantation, compared to HIV-uninfected (HIV-) candidates1–5. Organs from HIV+ donors (HIV D+) can now be transplanted into HIV+ recipients (HIV R+) following the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act of 20136,7. Currently, HIV D+/R+ transplants must occur as research and in accordance with HOPE Safeguards and Research Criteria published by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in November 2015 (Table 1)8.

Table 1:

HOPE Safeguards and Research Criteria, as published by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as a Final Rule in November 2015

| Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Donor Eligibility | |

| All HIV-positive deceased donors | No evidence of invasive opportunistic complications of HIV infection. |

| Pre-implant donor organ biopsy. | |

| Viral load: no requirement. CD4 count: no requirement. | |

| Deceased donor with known history of HIV infection and prior antiretroviral therapy (ART) | The study team must describe the anticipated post-transplant antiretroviral regimen(s) to be prescribed for the recipient and justify its conclusion that the regimen will be safe, tolerable, and effective. |

| HIV-positive living donor | Well-controlled HIV infection defined as: |

| • CD4+ T-cell count ≥500/µL for the 6-month period before donation | |

| • HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL | |

| • No evidence of invasive opportunistic complications of HIV infection | |

| Pre-implant donor organ biopsy | |

| Recipient Eligibility | CD4+ T-cell count ≥200/µL (kidney) |

| CD4+ T-cell count ≥100 µL (liver) within 16 weeks prior to transplant and no history of opportunistic infection (OI); or ≥200 µL if history of OI is present. | |

| HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL and on a stable antiretroviral regimen.* | |

| No evidence of active opportunistic complications of HIV infection | |

| No history of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). | |

| Transplant Hospital Criteria | Transplant hospital with established program for care of HIV-positive subjects |

| HIV program expertise on the transplant team. | |

| Experience with HIV-negative to HIV-positive organ transplantation. | |

| Standard operating procedures (SOPs) and training for the organ procurement, implanting/operative, and postoperative care teams for handling HIV-infected subjects, organs, and tissues. | |

| Institutional review board (IRB)-approved research protocol in HIV-positive to HIV-positive transplantation. | |

| Institutional biohazard plan outlining measures to prevent and manage inadvertent exposure to and/or transmission of HIV | |

| Provide each living HIV-positive donor and HIV-positive recipient with an “independent advocate”. | |

| Policies and SOPs governing the necessary knowledge, experience, skills, and training for independent advocates. | |

| OPOPO Responsibilities | SOPs and staff training procedures for working with deceased HIV-positive donors and their families in pertinent history taking; medical chart abstraction; the consent process; and handling blood, tissues, organs, and biospecimens. |

| Biohazard plan to prevent and manage HIV exposure and/or transmission | |

| Prevention of Inadvertent Transmission of HIV | Each participating Transplant Program and OPO shall develop an institutional biohazard plan for handling organs from HIV-positive donors that is designed to prevent and/or manage inadvertent transmission or exposure to HIV. |

| Procedures must be in place to ensure that human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps) are not recovered from HIV-positive donors for implantation, transplantation, infusion, or transfer into a human recipient; however, HCT/Ps from a donor determined to be ineligible may be made available for nonclinical purposes. | |

| Required Outcome Measures | |

| Waitlist Candidates | HIV status |

| CD4+ T-cell counts | |

| Co-infection (hepatitis C virus [HCV], hepatitis B virus [HBV] | |

| HIV viral load | |

| ART resistance | |

| Removal from waitlist (death or other reason) | |

| Time on waitlist | |

| Donors (all) | Type (Living or deceased) |

| HIV status (HIV-infected [HIV-positive] new diagnosis, HIV-positive known diagnosis) | |

| CD4+ T-cell count | |

| Co-infection (HCV, HBV) | |

| HIV viral load | |

| ART resistance | |

| Living Donors | Progression to renal insufficiency in kidney donors |

| Progression to hepatic insufficiency in liver donors | |

| Change in ART regimen as a result of organ dysfunction | |

| Progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) | |

| Failure to suppress viral replication (persistent HIV viremia) | |

| Death | |

| Transplant Recipients | Rejection rate (annual up to 5 years) |

| Progression to AIDS | |

| New OI | |

| Failure to suppress viral replication (persistent HIV viremia) | |

| HIV-associated organ failure | |

| Malignancy | |

| Graft failure | |

| Mismatched ART resistance versus donor | |

| Death | |

Patients who are unable to tolerate ART due to organ failure or who have recently started ART may have an HIV > 50 copies/mL and still be eligible if the study team anticipates an effective antiretroviral regimen for the patient after transplantation.

Successful implementation of HIV D+/R+ transplantation requires that transplant centers are appropriately informed and prepared for this practice. This includes knowing: that HIV D+/R+ transplants are legal and limited to research protocols8, the estimated size of the annual HIV+ deceased donor organ pool 9–11, the number of HIV D+/R+ transplants performed worldwide12–15, reported outcomes for HIV D−/R+ transplants16–21, and awareness of the HHS Safeguards and Research Criteria8. The enactment of federally mandated criteria for research protocols is unprecedented in solid organ transplantation, and disagreement with criteria could limit implementation. Additionally, variability in transplant centers’ knowledge about risks, management challenges, and outcomes of HIV+ transplants could affect HIV D+/R+ research protocols22.

We aimed to describe the scope of HIV D+/R+ transplantation planning among US transplant centers and to assess knowledge and attitudes about HIV+ transplantation, in order to determine potential transplant center barriers to implementation.

METHODS

Survey Distribution

We used Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) data to identify 209 transplant centers that had performed ≥1 solid organ transplant from 1/1/2014–6/3/2014. Centers that only performed pediatric transplants were excluded (n=38). We compiled a convenience sample of one representative of the transplant team at 204 centers through center websites, personal connections, PubMed, and calls to administrators; contact information for 5 centers was unavailable. Survey invitations were sent to this representative contact who was asked to forward the survey to someone on their transplant team who could best represent the center’s planned practice of HIV D+/R+ transplantation. The web-based survey was hosted by Qualtrics and distributed between 1/29/2016–6/8/2016. Non-respondents were sent three reminders. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board acknowledged this study as exempt.

Survey Design

Respondents were asked to respond to the survey on behalf of their transplant center. The survey consisted of 26 items regarding participant specialty/role, number of HIV+ candidates on their waitlist, center opinions on the HHS safeguards and research criteria, perceptions of HIV+ waitlist candidates at their center, planned practice of HIV D+/R+ transplants, and perceived risk of HIV D+/R+ transplants. The survey also included five multiple-choice and true/false-style questions assessing knowledge of HIV D+/R+ transplants (awareness that HIV D+/R+ transplants are legal, awareness that HIV D+/R+ transplants are limited to research, awareness of the HHS Safeguards and Research Criteria8, knowledge of the number of HIV D+/R+ transplants done worldwide12–15, and knowledge of the estimated size of the annual HIV+ deceased donor organ pool9,10), and six multiple-choice questions assessing knowledge of HIV-negative to HIV-positive (HIV D−/R+) transplants (impact of center experience, NIH study participation, and transplant era [2004–2007 and 2008–2011] on outcomes as published in the literature16–18, and risk of acute rejection, graft survival, and patient survival in HIV D−/R+ transplants compared to HIV D−/R− transplants as published in the literature16–21,23) (Appendix 1). The survey was pilot tested by two transplant surgeons, an infectious disease physician, and a statistician, and was revised based on feedback prior to distribution.

Data Sources

SRTR data was used to identify transplant centers and to supplement analyses of the primary survey data. The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. County-level HIV prevalence was obtained from AIDSVu (2013) (Center for AIDS Research, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health in partnership with Gilead Sciences, Inc24).

Center Factors and Survey Responses

Using SRTR data, we calculated the number of kidney, liver, pancreas, heart, and lung transplants performed annually at participating centers from 1/1/2010–5/31/2016. To characterize center experience with HIV R+ transplantation, we calculated the total number of HIV+ recipients transplanted each year. As a measure of center willingness to use higher-risk allografts, we calculated the percentage of transplants that involved increased-infectious risk donors (IRD). Using AIDSVu 2013 All County Prevalence Data, we determined HIV prevalence in the county in which each center was located24. Based on plans for HIV D+/R+ protocols (planning vs. not planning, as reported in the survey), we compared centers in terms of transplant volume, HIV R+ volume, IRD use, knowledge of HIV D+/R+ transplants, and knowledge of HIV D−/R+ transplants using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14.2 SE (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 114 centers responded, including at least one center from each UNOS region (response rate=56%). The most common respondent role/specialty was surgery (49%), followed by infectious disease (15%) (Table 2). Among responding centers, median annual transplant volume was 93 (range 2–190), median annual volume of HIV+ recipients was 0 (range 0–7), median proportion of IRD donor organs used was 14% (range 2%−44%), and median county HIV prevalence was 419 per 100,000 (range 0–2,286) (Table 2). Number of HIV+ candidates on an organ transplant waitlist was not captured in SRTR at the time of this survey; as reported by survey respondents, the median number of HIV+ candidates was 3 (range 0–52). The total number of HIV+ transplant candidates of all organ types reported by all centers was 803.

Table 2: Study Population.

Characteristics of respondents and their centers. Center characteristics were found using SRTR and AIDSVu data.

| Respondent Characteristics | N=104 (%) |

|---|---|

| Surgeon | 51 (49%) |

| Transplant Surgeon | 50* (48%) |

| Vascular Surgeon | 1 (1%) |

| Physician | 34 (32%) |

| Infectious Disease | 16 (15%) |

| Hepatology | 8 (8%) |

| Nephrology | 7* (6%) |

| Cardiology | 1 (1%) |

| Transplant physician (not specified) | 2 (2%) |

| Nurse or Coordinator | 9 (9%) |

| Pharmacist | 8 (8%) |

| Administrator | 3 (3%) |

| Transplant Center Characteristics | Median (IQR) |

| Annual Transplant Volume (all organs) |

93 (33-189) |

| Volume of HIV+ recipients (all organs) |

0 (0-1) |

| Proportion IRD Organs (all organs) |

14% (11%-17%) |

| County HIV Prevalence (per 100,000) |

418.5 (238-641) |

One respondent reported being both a transplant surgeon and nephrologist

Planned Practice of HIV D+/R+ Transplants

Fifty respondents (43.8%) reported that their centers are planning to perform HIV D+/R+ transplants. Specific programs planning HIV D+/R+ transplants included kidney (n=48, 98.0%), liver (n=34, 68.0%), pancreas (n=8, 16.0%), heart (n=2, 4.0%) and lung (n=1, 2.0%). At least one center in each UNOS region reported planning to perform HIV D+/R+ transplants. However, most centers planning HIV D+/R+ protocols were located in the eastern U.S. (n=28, UNOS regions 1, 2, 3, 9, 11), with 4 centers on the west coast (Regions 5, 6) and 18 in central U.S. (Regions 4, 7, 8 10).

Transplant centers planning to implement HIV D+/R+ transplantation had 2.9-fold higher median transplant volume (159 vs. 54, p<0.01), higher median volume of HIV+ transplant recipients (1 vs. 0, p<0.01), higher proportion of transplants using IRD organs (15% vs. 12%, p<0.01), and a higher county prevalence of HIV (541 vs. 321 per 100,000, p<0.01) compared to centers not planning to implement HIV D+/R+ transplantation (Table 3).

Table 3: Center level characteristics among centers planning and not planning HIV positive-to-positive transplants (Median (IQR)).

The mean annual transplant volume, mean annual number of HIV+ recipients, and proportion of organs from each center that were IRD at each center from 1/1/2010-12/31/2015 was calculated. The median (IQR) of these means and proportions is presented.

| Planning N=50 55.6% |

Not Planning N=40 44.4% |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual transplant volume | 159 (79-303) | 54 (30-123) | <0.001 |

| Volume of HIV+ recipients | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-0) | <0.001 |

| Proportion IRD organs | 15% (13%-19%) | 12% (9%-16%) | 0.003 |

| County HIV prevalence (per 100,000) | 541 (281-1092) | 321 (155-470) | 0.003 |

| Reported number of HIV+ patients on the waitlist | 8 (3-14) | 0 (0-3) | <0.001 |

Preparedness to transplant HIV+ organs: knowledge of the HOPE Act and HIV+ transplantation

Of respondents, 104 (91.2%) were aware that HIV D+/R+ is legal. Twenty-four (21.4%) were unaware that HIV D+/R+ transplants must occur under research protocols in accordance with HHS criteria; of those unaware, 5 reported planning HIV D+/R+ protocols. Of respondents, 40.2% had reviewed the HOPE Safeguards and Research Criteria.

Among centers planning HOPE protocols, overall knowledge of HIV D+/R+ transplants reported in the peer-reviewed literature was high (Table 4). Of respondents planning HOPE protocols, 54.5% correctly identified the number of HIV D+/R+ transplants that had been reported worldwide at the time of survey distribution (15–45 HIV D+/R+ transplants were reported by June 8 201612−15) and 58.0% correctly identified the estimated size of the HIV+ deceased organ donor pool each year (200–600 potential HIV+ organ donors per year9,10).

Table 4: Knowledge of HIV D+/R+ transplants and HIV D−/R+ transplants among centers planning HIV D+/R+ transplants.

Overall knowledge scores: Respondents were asked 5 questions regarding about research or reports regarding HIV D+/R+ transplants and the HOPE Act, and 6 questions regarding HIV D−/R+ transplants. Overall knowledge scores are the percent of questions on each of these topics that were answered correctly. The median (IQR) knowledge scores are reported.

Knowledge of HIV D+/R+ transplants, the HOPE Act, and outcomes of HIV D−/R+ transplants: The percent of respondents who answered each question correctly is reported.

| Overall knowledge scores | |

|---|---|

| Overall knowledge score: HIV D+/R+ transplants (median (IQR)) |

83.3% (50.0%-100%) |

| Overall Knowledge score: HIV D−/R+ transplants (median (IQR)) |

83.3% (66.6%-83.3%) |

| Knowledge of HIV D+/R+ transplants | |

| Number of HIV D+/R+ transplants reported worldwide | 54.0% |

| Estimated annual size of HIV+ deceased organ donor pool | 58.0% |

| Knowledge of HOPE Act | |

| Aware that HIV D+/R+ transplants are legal in the US | 92.0% |

| Aware that HIV D+/R+ transplants are restricted to research in the US | 90.0% |

| Have read the HOPE Safeguards and Research Criteria | 64.0% |

| Knowledge of outcomes of HIV D−/R+ transplants | |

| No difference in outcomes based on center experience | 36.9% |

| No difference in outcomes based on participation in NIH funded multi-site trial of HIV D−/R+ transplants | 86.9% |

| Transplant era associated with HIV D−/R+ transplant outcomes | 82.6% |

| HIV D−/R+ transplants at increased risk of acute rejection compared to HIV D−/R− transplants | 84.8% |

| Graft survival among HIV D−/R+ transplant recipients comparable to HIV D−/R− transplants | 78.3% |

| Patient survival among HIV D−/R+ transplant recipients comparable to HIV D−/R− transplants | 89.1% |

Most respondents planning HOPE protocols correctly responded that published studies demonstrate equivalent patient survival (89.1%) and graft survival (78.3%) but higher rates of rejection (84.8%) for HIV D−/R+ recipients. Of respondents planning HOPE protocols, 82.6% were also aware that later transplant era has been reported as a predictor of improved outcomes for HIV+ transplant recipients. However, 36.9% of respondents planning HOPE protocols believed that there is a difference in recipient outcomes among centers that have performed <5 HIV D−/R+ transplants compared to centers that have performed >5 HIV D−/R+ transplants (Table 4).

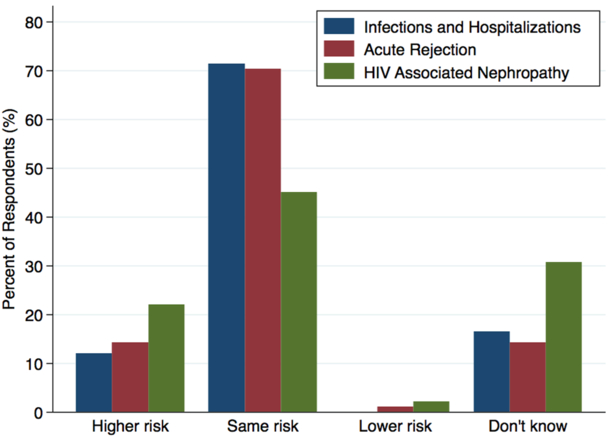

Perceived Risks of HIV D+/R+ transplants compared to HIV D−/R+ transplants

The risk of HIV superinfection, defined as infection with a second distinct strain of HIV in HIV D+/R+ transplants, was perceived to be a moderate and clinically manageable risk by 72.5% of respondents; only 6.6% perceived the risk to be high and clinically dangerous. Of respondents, 21.9% perceived the risk of HIV-associated nephropathy to be higher in HIV D+/R+ transplants compared to HIV D−/R+ transplants; 30.8% said they did not know how the risks would compare (Figure 1). The risks of acute rejection and infections/hospitalizations were perceived to be comparable to HIV D−/R+ transplants by 70.3% and 71.4% of respondents, respectively (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in perceived risks of HIV D+/R+ transplants between centers planning and not planning HOPE protocols.

Figure 1: Perceived risk of HIV positive-to-positive transplants compared to HIV negative-to-positive.

Respondents were asked to predict the risk of HIV D+/R+ transplants compared to HIV D−/R+ transplants in terms of three outcomes: infections and hospitalizations; acute rejection; and HIV associated nephropathy.

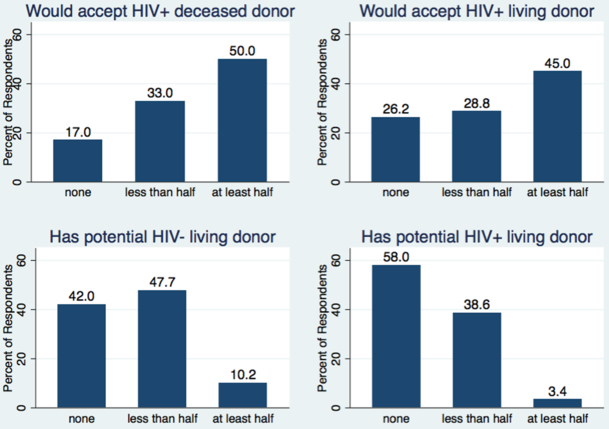

Perceptions of HIV+ Candidates Willingness to Accept HIV D+/R+ transplants and Anticipated Access to HIV+ Living Donation

Of respondents, 50.0% anticipated that at least half of their HIV+ waitlist patients would be willing to accept an HIV+ deceased donor organ, and 45.0% anticipated that at least half of their HIV+ waitlist patients would be willing to accept an HIV+ living donor organ. However, 17.0% of respondents anticipated that none of their HIV+ waitlist patients would be willing to accept an HIV+ deceased donor organ, and 26.2% anticipated that none of their HIV+ waitlist patients would be willing to accept an HIV+ living donor (Figure 2). Respondents reporting that more than half of their HIV+ waitlist patients would be willing to accept HIV+ deceased donor organs were more likely to be planning to perform HIV D+/R+ transplants (68.8% vs. 27.5%, p<0.001).

Figure 2: Respondent Perceptions of HIV+ Patients on Organ Waitlists.

Respondents were asked to predict what proportion of the HIV+ patients on waitlists at their center would accept an HIV+ deceased or living donors, and what proportion have access to living donation.

Thirteen centers reported that none of their patients would accept either HIV+ living or deceased donors. Of those who reported that none of their patients would accept an HIV+ living donor, four were planning HOPE protocols. Of those who reported that none of their patients would accept an HIV+ deceased donor, one was planning a HOPE protocol.

No respondents believed that most or all of their HIV+ waitlist patients have potential HIV+ living donors, and 58.0% believe that none of their HIV+ waitlist patients have potential HIV+ living donors. Likewise, only 10.2% believe that at least half of their HIV+ waitlist patients have potential HIV- living donors and 42.0% believe that none of their HIV+ waitlist patients have potential HIV- living donors (Figure 2).

Agreement with the HOPE Safeguards and Research Criteria

Most respondents agreed with the HHS deceased donor criteria regarding excluding donors with opportunistic infections (92.7%) and the requirement to obtain pre-implantation donor organ biopsies (71.9%, Table 5). However, 22.9% of respondents believed the criterion allowing deceased donors with any HIV viral load was too lenient (Table 5). Of those believing this criterion was too lenient, 16 (76.2%) said they would only allow donors with low or undetectable viral loads. Of respondents, 53.2% disagreed with the criteria for center and study team experience with HIV+ transplantation (Table 5); 40.4% of respondents believed the criteria should not be organ specific, and 12.8% of respondents believed there should be no experience criteria (Table 5). Respondents from centers planning to perform HIV D+/R+ transplants were more likely to agree with the general center experience criteria with HIV+ recipients (56.0% vs 22.5%) than centers not planning protocols but they were less likely to believe that the required experience should be organ specific (28.0% vs 40.0%) (p=.011).

Table 5: Attitudes on HIV+ Deceased and Living Donor Eligibility.

Respondents degree of agreement with the HOPE Safeguards and Research Criteria.

| Transplant Center and Study Team Experience Criteria | Agree |

Agree: but should not be organ specific |

Neutral | Disagree: should be no experience criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transplant physician and HIV physician collectively have experience with at least 5 HIV D−/R+ transplants with the designated organs over the last four years | 35.1 | 40.4 | 11.7 | 12.8 |

| HIV+ Deceased Donor Criteria | Agree | Neutral | Disagree too lenient |

Disagree too strict |

| No evidence of invasive opportunistic infections | 92.7 | 5.2 | 0 | 2.1 |

| Pre-implant donor organ biopsy | 71.9 | 22.9 | 0 | 5.2 |

| Viral load: any viral load is allowed given effective post-transplant antiretroviral regimen is justified | 55.2 | 20.8 | 22.9 | 1.0 |

| HIV+ Living Donor Criteria | Agree | Neutral | Disagree too lenient |

Disagree too strict |

| CD4+ T-cell count >500/µL for the 6-month period before donation | 84.8 |

7.6 |

2.5 |

5.1 |

| HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL | 89.9 | 7.6 | 2.5 | 0 |

| No evidence of invasive opportunistic complications of HIV infection | 97.5 |

2.5 |

0 | 0 |

| Pre-implant donor organ biopsy | 56.9 | 26.6 | 0 | 16.5 |

Of centers planning HIV D+/R+ protocols, 6 (12%) reported planning to implement protocols more restrictive than the minimum HHS Safeguards. Three plan to include additional viral load requirements, one to exclude HCV co-infected donors, and one to exclude living donors.

Opinions on HIV+ Living Donation

Among respondents, 83.2% believed HIV+ living donors should be allowed to donate to an HIV+ recipient given a certain set of criteria. Most respondents agreed with existing HHS criteria on HIV living donation, including excluding donors with opportunistic infections, requiring a CD4+ T-cell count over 500 cells/µL and an undetectable HIV viral load (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In a national survey, 50 transplant centers reported plans to perform HIV D+/R+ transplants. Although many programs plan to implement HIV D+/R+ protocols, most reported planning to perform kidney (98.0%) and liver (68.0%), while few centers reported planning pancreas, heart and liver transplants. This raises concerns that OPOs may not invest resources in evaluating HIV+ potential donors who would likely only be able to donate three organs. In addition, there was regional clustering of centers planning protocols. While ≥1 center in every UNOS region reported planning HIV D+/R+ protocols, fewer centers in the west coast or middle of the U.S. were planning protocols, compared to the eastern US. Patients in those areas may have lower access to HIV D+/R+ transplants, and OPOs in those regions may be less likely to evaluate potential HIV+ donors if local transplant programs will not use the organs.

Many centers (56.2%) reported no plans to perform HIV D+/R+ transplants. Unsurprisingly, centers not planning HIV D+/R+ protocols had lower median transplant volume, lower median volume of HIV+ transplant recipients, lower proportion of transplants using IRD organs, and lower HIV prevalence in their surrounding county (p<0.01). Centers not planning HIV D+/R+ protocols were more likely to believe their HIV+ candidates would be unwilling to accept HIV+ donor organs compared to centers planning protocols (p<0.001).. On the contrary, recent studies indicate high willingness to accept HIV+ organs among people with HIV25,26. Broader dissemination of these findings combined with advocacy from the HIV+ community could address this potential barrier to implementation.

Overall, centers planning HIV D+/R+ protocols were informed about the HOPE Act and HIV D−/R+ transplants, indicating that these centers are aware of the restrictions of HOPE protocols and the challenges of HIV+ transplantation. Furthermore, respondents reported agreement with most of the HHS safeguards and research criteria required to carry out HOPE transplants.

Despite broad knowledge and support of the HOPE act safeguards and criteria, there was ambivalence or disagreement surrounding the criterion limiting HIV D+/R+ transplants to centers where the transplant and HIV physician collectively have experience with at least 5 HIV D−/R+ transplants with the designated organs within the past four years. Likewise, among centers planning HIV D+/R+ transplants, many were unaware that center number of HIV D−/R+ transplants has not been associated with recipient outcomes 18. Transplant community stakeholders voiced equipoise regarding this criterion prior to the publication of the Safeguards and Research Criteria; our survey further reflects this controversy. Disagreement over this requirement may partially explain why most planned HIV D+/R+ protocols are limited to kidney and liver.

The inclusion of HIV+ living donors in the HHS Safeguards and Research Criteria was also controversial, given concerns about potentially increased risk of end-stage renal disease after nephrectomy for HIV+ living donors22,27. However, our study found that most centers (83.2%) support HIV D+/R+ living donation. This perception is supported by a recent study demonstrating that HIV+ individuals with well-controlled HIV have a similar risk of ESRD as their HIV-uninfected counterparts28. Furthermore, recent studies have found that people living with HIV are willing to be living organ donors26,29.

This study has several limitations. We were limited by a response rate of 55%; however, this is a higher response rate than typically seen from transplant center surveys, and there was representation from all UNOS regions. Furthermore, respondents were asked to respond as a representative of their center’s opinions, however it is possible they did not accurately reflect their center’s positions or intended practice. The convenience sample and distribution method, where recipients were asked to forward the survey to the best representative of their center’s HIV+ transplant practice, may have caused response inaccuracies. However, we felt transplant centers were best able to identify the individual at their center most knowledgeable about HIV+ transplantation and thus selection based on these criteria was encouraged.

Overall, we found broad support for HIV D+/R+ transplantation among US transplant centers, and centers planning HOPE protocols appear to be well-informed regarding HIV D+/R+ and HIV D−/R+ transplants. However, transplant center barriers to implementation of the HOPE Act exist, such as regional clustering of participating centers, a focus on kidney and liver transplantation, the perception that center experience with HIV D−/R+ transplants is associated with superior outcomes, and perceptions that HIV+ transplant candidates would not accept HIV+ donor organs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants K23CA177321–01A1 (Durand), R34AI123023 (Durand), U01AI134591 (Durand, Segev), 1R01AI120938–01A1 (Tobian), K24DK101828 (Segev), F30DK116658 (Shaffer), and Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research 1P30AI094189 (Durand).

References

- 1.Stosor V Organ Transplantation in HIV Patients: Current Status and New Directions. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2013;15(6):526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ragni MV, Eghtesad B, Schlesinger KW, Dvorchik I, Fung JJ. Pretransplant survival is shorter in HIV-positive than HIV-negative subjects with end-stage liver disease. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2005;11(11):1425–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subramanian A, Sulkowski M, Barin B, et al. MELD is an Important Predictor of Pre-Transplant Mortality in HIV-Infected Liver Transplant Candidates. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(1):159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trullas JC, Cofan F, Barril G, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in HIV-1-infected patients on dialysis in the cART era: a GESIDA/SEN cohort study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2011;57(4):276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uriel N, Nahumi N, Colombo PC, et al. Advanced heart failure in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: is there equal access to care? The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2014;33(9):924–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyarsky BJ, Segev DL. From Bench to Bill: How a Transplant Nuance Became 1 of Only 57 Laws Passed in 2013. Annals of Surgery. 2016;263(3):430–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyarsky BJ, Durand CM, Palella FJ, Segev DL. Challenges and Clinical Decision‐Making in HIV‐to‐HIV Transplantation: Insights From the HIV Literature. American Journal of Transplantation. 2015;15(8):2023–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins F Final Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act Safeguards and Research Criteria for Transplantation of Organs Infected With HIV. In: Department of Health and Human Services, ed. Vol 802015:73785–73796. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyarsky BJ, Hall EC, Singer AL, Montgomery RA, Gebo KA, Segev DL. Estimating the potential pool of HIV-infected deceased organ donors in the United States. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2011;11(6):1209–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richterman A, Sawinski D, Reese PP, et al. An Assessment of HIV-Infected Patients Dying in Care for Deceased Organ Donation in a United States Urban Center. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2015;15(8):2105–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cash A, Luo X, Chow EKH, et al. HIV+ Deceased Donor Referrals: A National Survey of Organ Procurement Organizations. Clinical Transplantation.32(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller E, Barday Z, Mendelson M, Kahn D. HIV-Positive–to–HIV-Positive Kidney Transplantation — Results at 3 to 5 Years. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(7):613–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calmy A, van Delden C, Giostra E, et al. HIV-Positive-to-HIV-Positive Liver Transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2016;16(8):2473–2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hathorn E, Smit E, Elsharkawy AM, et al. HIV-Positive–to–HIV-Positive Liver Transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(18):1807–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiv Malani P. and transplantation: New reasons for hope. JAMA. 2016;316(2):136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locke JE, Durand C, Reed RD, et al. Long-term Outcomes After Liver Transplantation Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Recipients. Transplantation. 2016;100(1):141–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Locke JE, Mehta S, Reed RD, et al. A National Study of Outcomes among HIV-Infected Kidney Transplant Recipients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015;26(9):2222–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locke JE, Reed RD, Mehta SG, et al. Center-Level Experience and Kidney Transplant Outcomes in HIV-Infected Recipients. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2015;15(8):2096–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stock PG. A Source of Treatment for Those Who Were (Almost) Lost: Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive to Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Kidney Transplantation-Results at 3 to 5 Years. Transplantation. 2015;99(9):1744–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stock PG, Barin B, Murphy B, et al. Outcomes of Kidney Transplantation in HIV-Infected Recipients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(21):2004–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miro JM, Montejo M, Castells L, et al. Outcome of HCV/HIV-coinfected liver transplant recipients: a prospective and multicenter cohort study. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2012;12(7):1866–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haidar G, Singh N. The Times, They are a-Changing: HOPE for HIV-to-HIV Organ Transplantation. Transplantation. 2017;101(9):1987–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trullas JC, Mocroft A, Cofan F, et al. Dialysis and Renal Transplantation in HIV-Infected Patients: a European Survey. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes JAIDS. 2010;55(5):582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AIDSVu (www.aidsvu.org). Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huda T, Katie N, Archik D, Satyajit D. Attitude of patients with HIV infection towards organ transplant between HIV patients. A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2015;27(1):13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen AQ, Anjum SK, Halpern SE, et al. Willingness to Donate Organs among People Living with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes JAIDS. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucas GM, Ross MJ, Stock PG, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients Infected With HIV: 2014 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014;59(9):e96–e138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muzaale AD, Althoff KN, Sperati CJ, et al. Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease in HIV-Positive Potential Live Kidney Donors. American Journal of Transplantation. 2017;17(7):1823–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Henderson ML, Bollinger J, et al. Perceptions, motivations, and concerns about living organ donation among people living with HIV. AIDS care. 2018:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.