To The Editor

Nocturnal atopic dermatitis (AD) flares affect over 60% of children with AD, and are associated with sleep disturbance.1,2 Little is known about the underlying rhythm of these highly pruritic flares, and whether treatment with sedating antihistamines alters nocturnal motor activity due to itch.1,3 We hypothesized that nighttime scratching in AD has a rhythm.

To evaluate our hypothesis, we performed a case-control study with children aged 6-17 years with moderate/severe AD and healthy age/gender matched controls. Demographic details of the study population have been published.4 Participants were 65% male, mean age±standard deviation (SD) 11.0±3.2 years in AD (n=20) versus controls (n=20)11.5±3.3(p=0.68). Moderate/severe AD was defined by a SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) score >25, our patients ranged from 28-92, µ±SD=42±17. Disease severity (SCORAD) correlated with Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO), r (spearman) =0.61, p<0.01, n=19. Nocturnal movements and sleep were assessed in 19 AD patients and 19 controls via home activity monitor, actigraphy (Actiwatch Spectrum, Philips Respironics, Bend, OR) and sleep diary for 3-7 nights. Data were analyzed using Philips Actiware 6 software (Philips Respironics, Bend, OR).

Activity counts, recorded as total movement count (raw data output summed from the watch over 30 minute bins) were averaged across nights. Sleep onset was set as time zero to standardize assessments between children of different ages. Data were averaged across subjects in AD versus control groups Generalized least squares models, with cubic splines for smoothing, were fit to the data. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to identify the most suitable correlation structure for the model. All analyses were performed using the R package ‘rms.

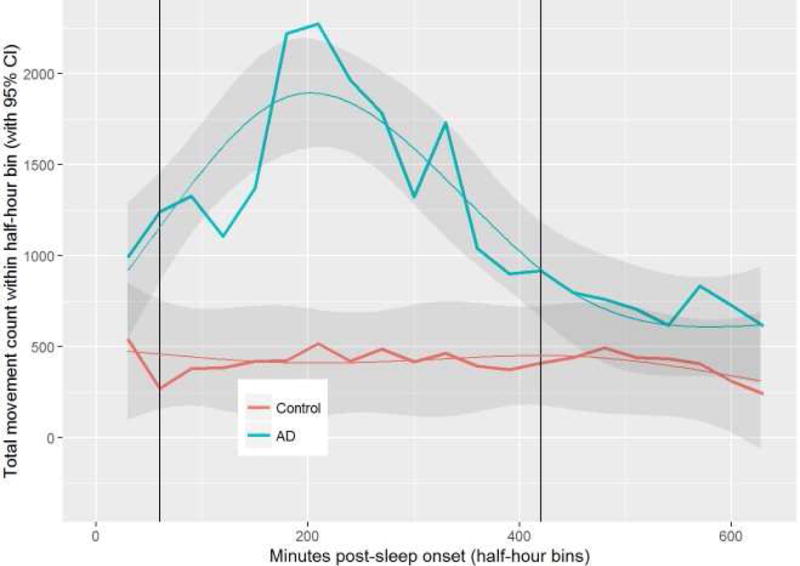

Nocturnal activity bouts were increased in AD versus controls between 1-6 hours after sleep onset (p<0.001). Peak non-dominant wrist movements clustered 3 hours after sleep onset, with an average activity count difference between AD and control patients of 1488 (95% Confidence Interval 1085-1892) (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Total Movement Counts Peak Three Hours After Sleep Onset In Atopic Dermatitis.

Average total movement count is plotted on the Y-axis, with minutes post-sleep onset on the X-axis. Plot of mean observed and model predicted values (smoothed lines) with 95% confidence intervals as the shaded region in AD (n=19) versus controls (n=19). Groups are significantly different in the region between the vertical lines.

AD and control patients differ (p<0.001). The interaction between group and time is significant (p<0.001). There is also a significant time effect and it is not linear.

Although patients were instructed to avoid oral antihistamine use during the study, seven patients deviated from the study protocol (Table I). Five patients took antihistamine on some nights, allowing a comparison of nights with (n=10) versus without antihistamine (n=22) within the same subject. This demonstrated no difference with respect to total movement (p=0.82). The interaction between group and time was not significant (p=0.77). This small sub analysis suggests that antihistamine treatment may not affect nocturnal scratch rhythm.

Table I.

Characteristics of Patients taking antihistamines (n=7).

| Patient Number | name of antihistamine used | nights on antihistamine | nights off antihistamine | mean WASO on antihistamine | mean WASO off antihistamine | P-value* | mean Sleep onset Latency on antihistamine | mean Sleep onset Latency off antihistamine | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient1 | cetirizine | 1 | 5 | 129.5 | 154.4 | 0.80 | 0.0 | 52.6 | 0.14 |

| Patient2 | diphenhydramine | 2 | 3 | 66.0 | 106.7 | 0.08 | 28.0 | 45.2 | 0.25 |

| Patient3 | cetrizine | 2 | 5 | 158.5 | 106.2 | 0.44 | 22.5 | 2.4 | 0.03 |

| Patient4 | hydroxyzine | 7 | 0 | 154.9 | 1.8 | ||||

| Patient5 | hydroxyzine | 1 | 6 | 74.5 | 67.6 | 0.78 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 0.27 |

| Patient6 | hydroxyzine | 7 | 0 | 295.7 | 0†† | ||||

| Patient7 | one night levocetirizine, other nights hydroxyzine | 4 | 3 | 86.1 | 95.0 | 0.48 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 0.59 |

Mann-Whitney U test

Severely fragmented sleep and sleep onset latency was computed as 0 minutes for all nights

Patients on antihistamines trended towards having more severe disease (SCORAD µ=70.4±19.7 (n=7 subjects) v. 50.7±20.3 (n=12), p=0.06). Sleep onset latency trended to be shorter on antihistamine versus non-antihistamine nights (µ=5.2±3.8 minutes (n=24 nights) v. 15.6±1.9 (n=97), p=0.07). Minutes of Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO) were higher on the nights of antihistamine use (µ=173.0±11.1 minutes (n=24 nights) v. 88.2±5.5 (n=97), p<0.01); it is possible that antihistamines were used intermittently because of increased AD severity.

Limitations included the small size of the cohort and number of patients taking antihistamine. Nighttime movements likely represented scratching, but this could not be confirmed.

Most nocturnal scratch behavior in AD occurs 1-6 hours after sleep onset, not in the first hour and peaking at 3 hours. This timing suggests a pattern to scratching, which could potentially be targeted for treatment. This pattern might not be attenuated by antihistamine. Consistent with our data, sedating antihistamines are often used to induce sleep but are not thought to affect itch.5 Timing of nocturnal AD flares could be related to sleep physiology, circadian rhythms of skin barrier, and/or circadian immunology.1 Further understanding of these mechanisms and implementing timed treatments could allow for the development of personalized AD therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: The Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (AF), American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Young Faculty Support Award (AF), and the Society for Pediatric Dermatology William Weston Grant (AP). This project was supported by grant number K12HS023011 (AF) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Corporate Sponsors: none

This study was IRB approved.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None Declared.

References

- 1.Fishbein AB, Vitaterna O, Haugh IM, et al. Nocturnal eczema: Review of sleep and circadian rhythms in children with atopic dermatitis and future research directions. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;136:1170–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamlin SL, Mattson CL, Frieden IJ, et al. The price of pruritus: sleep disturbance and cosleeping in atopic dermatitis. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2005;159:745–50. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bender BG, Ballard R, Canono B, Murphy JR, Leung DY. Disease severity, scratching, and sleep quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;58:415–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: A case-control study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018;78:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Clinical practice. Chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1625–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1208814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]