Abstract

Antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase (GPx) decomposes hydroperoxides by utilizing the different redox chemistry of the selenium and sulfur. Here, we report a Se-catalysed para-amination of phenols while, in contrast, the reactions with sulfur donors are stoichiometric. A catalytic amount of phenylselenyl bromide smoothly converts N-aryloxyacetamides to N-acetyl p-aminophenols. When the para position was substituted (for example, with tyrosine), the dearomatization 4,4-disubstituted cyclodienone products were obtained. A combination of experimental and computational studies was conducted and suggested the weaker Se−N bond plays a key role in the completion of the catalytic cycle. Our method extends the selenium-catalysed processes to the functionalisation of aromatic compounds. Finally, we demonstrated the mild nature of the para-amination reaction by generating an AIEgen 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole (HBT) product in a fluorogenic fashion in a PBS buffer.

Selenium has emerged as a metalloid for the catalytic construction of C–N bonds; however no functionalisation of aromatic compounds has been developed yet. Here, the authors report the para-amination of phenols via two successive sigmatropic rearrangements of a redox versatile Se–N bond.

Introduction

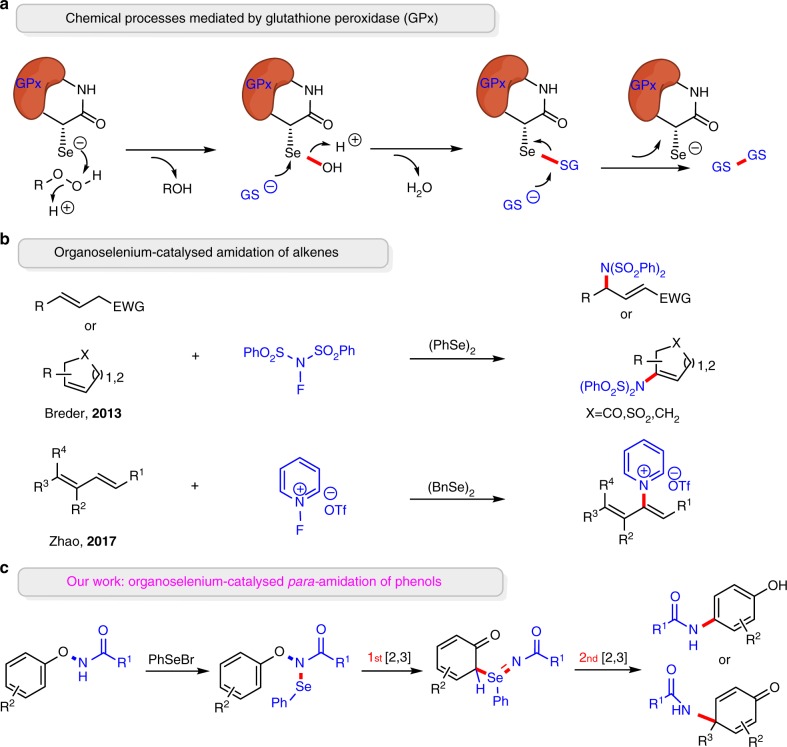

Selenium is an essential biological trace element discovered by Jöns Jacob Berzelius in 1818 1. The selenium analogue of cysteine, known as selenocysteine2–4 (Sec), is the main biological form of selenium. The most studied selenoenzyme glutathione peroxidase (GPx) has an Sec residue in its active site that is responsible for decomposing hydroperoxides (Fig. 1a)5,6. Besides, the flavin-containing redox enzyme thioredoxin reductase (TrxR)7–9 and the deiodinating enzyme iodothyronine deiodinase (ID)10,11 represent other key selenium-containing enzymes in biocatalysis.

Fig. 1.

Selected biological reaction and organic reactions catalysed by selenium. a Proposed catalytic cycle of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) for the reduction of hydroperoxides in biology. b Previous reports on organoselenium-catalysed amination of alkenes. GS− glutathione. c Our double [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement to achieve para-amination of phenols

Selenium-containing small molecules, such as ebselen and its analogues, have also exhibited important antioxidant activity as GPx mimics12–15. Organoselenium-catalysed reactions have been widely employed in a number of different reactions16–18, and substantial progress has been made by Breder19–21, Wirth22–24, Denmark25,26, Yeung27 and Zhao28–31 in recent years. Notably, selenium has emerged as appropriate alternatives to precious metals as catalysts for the construction of C–N bonds32–34. Breder et al. discovered an elegant selenium-catalysed amination of allyl and vinyl using N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide as oxidant and nitrogen source35. Furthermore, Zhao et al. accomplished a powerful pyridination of 1,3-dienes using (BnSe)2 as a catalyst36 (Fig. 1b). However, no selenium-catalysed processes for the functionalisation of aromatic compounds have been developed. One challenge might be the electrophilic selenium catalysts react with the aryl rings directly, leading to the deactivation of catalyst37,38. We thought that a more nucleophilic site, to accommodate with selenium catalyst temporarily, might be helpful for competing with the deactivation. We herein report a strategy to first form an intermediate with an adjacent, redox versatile Se–N bond which undergoes two successive sigmatropic rearrangements to generate the para-amination product and regenerate the selenium catalyst (Fig. 1c).

Results

Model reactions and substrate scope

We started by treating N-phenoxyacetamide (1a) with 1.0 equiv. of N-phenylselanylphthalimide (C1); we observed the para-aminated phenol (2a, acetaminophen) in 47% yield. To our delight, when catalytic amount of C1 (10 mol%) was used, 2a can be obtained in 38% yield (Supplementary Table 1, entries 1−3). This result compelled us to explore other organoselenium reagents that might catalyse this reaction. No product was detected when diphenyl diselenide (C2) and diphenylselane (C3) were used (Supplementary Table 1, entries 4 and 5). Both PhSeCl (C4) and PhSeBr (C5) proved to be efficient catalysts in 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) with 60 and 79% yields, respectively (Supplementary Table 1, entries 6 and 7). Screening of a variety of solvents (including MeOH, DMSO, THF, MeCN, EA) indicated that 1,4-dioxane was the best solvent (93% NMR yield and 90% isolated yield of the desired product, Supplementary Table 1, entries 8−13). Ultimately, the optimal reaction conditions employed 10 mol% PhSeBr (C5) in 1,4-dioxane at room temperature in air.

The optimized reaction conditions proved to be effective with a number of other substituents on N-phenoxyacetamides (Table 1). N-phenoxyacetamides with electron-rich or electron-deficient substituents reacted smoothly to give the desired para-C–H amination products (2a−k) in moderate to excellent yields (62−92%). Electronic effects did not significantly influence the outcomes of the reactions. N-phenoxyacetamides bearing fluoro-, bromo-, and chloro-substituents (2d−e, 2g−h, 2j) were successfully subjected to this simple protocol with yields from 62 to 83%. The reaction condition was applicable to yield aminated naphthol (2l) in 54% yield.

Table 1.

Substrate scope of Se-catalysed para-amination of phenolsa

|

aStandard conditions: 1 (0.20 mmol), PhSeBr (10 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (2.0 mL), at ambient temperature for 8 h. Isolated yield

To further expand the scope of this highly para-selective amination process, we investigated different N-phenoxyamides. N-phenoxyamide with the Boc-substituent on nitrogen afforded the corresponding product 2m in 76% yield. When the acetyl group was replaced by other aliphatic groups such as cyclopropanecarbonyl and hexanoyl groups, the reactions proceeded smoothly to afford the desired products 2n and 2o in 85 and 53% yield, respectively. Replacing the acetyl group with aromatic amides or sulfonamide also furnished the desired phenols (2p−t) in good yields (64−87%). When we applied the method to the late-stage modification of an antifungal drug Triclosan, the desired para-aminated product (2u) was isolated successfully in 83% yield.

The oxidative amination/dearomatization reaction

When the para-methyl-substituted substrate was employed, we obtained the dearomatization product 3a in 78% yield (Table 2). Efficient oxidative amination of phenols was also obtained when ethyl, propyl was present at the para site under standard reaction condition. However, we did not detect any of the dienones when methyl was replaced with bulkier substituents, such as isopropyl and tert-butyl groups. In those cases, only the corresponding phenols were isolated. Replacing the acetyl group with the propionyl or isobutyryl group on nitrogen gave 3f and 3g in 80 and 61% yield, respectively. Finally, protected tyrosine underwent oxidative amination to give 3h in 56% yield under standard conditions.

Table 2.

Substrate scope of Se-catalysed dearomatization reactiona

|

aStandard conditions: 1 (0.20 mmol), PhSeBr (10 mol%), 1,4-dioxane (2.0 mL), at ambient temperature for 8 h. Isolated yield

The stoichiometric sulfur-mediated reaction

The success in the Se-catalysed synthesis of p-aminophenols or dienones prompted us to attempt to develop a similar sulfur-catalysed version which could display good catalytic activity as organochalcogen catalysis39–43. However, when a solution of 1a was treated with 10 mol% 2-(p-tolylthio)isoindoline-1,3-dione (4a) at ambient temperature over a period of 5 h, we detected a trace amount of para-aminated product (5a) with a preserved N−S bond. When the amount of 4a was increased to 1.2 equiv., para-aminated product (5a) was obtained in 38% yield. An extensive screening of bases (e.g. pyridine, CsOAc, 2,6-lutidine, DMAP, Na2CO3, DBU, DIPEA) was conducted and revealed that 2,6-lutidine gave the desired para-aminated product 5a in 53% yield. Further optimization established TFE as the best solvent for this transformation, providing the para-aminated phenol in 84% isolated yield (Supplementary Table 2).

With the optimal reaction conditions established, we investigated a series of N-phenoxyacetamide substrates (Table 3). Ortho-substituted N-phenoxyacetamides delivered the desired para-aminated phenols in good to excellent yields (5a–5c). When the N-protecting group was replaced by other aliphatic amides such as cyclopropanecarbonyl and propionyl groups, the reactions proceeded smoothly to afford desired products 5e and 5f in 45 and 80% yield, respectively. The reaction proceeded smoothly with both substrates bearing electron-donating group (5h) and halogen-containing N-substituted phthalimides (5i–m).

Table 3.

Substrate scope of S-mediated reactiona

|

aStandard conditions: 1 (0.20 mmol), 4 (0.24 mmol), 2,6-lutidine (1.0 equiv.), TFE (2.0 mL), at ambient temperature for 5h Isolated yield. TFE, 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol

Mechanistic study

A series of experiments were conducted to probe the reaction mechanism. The ortho-sulfiliminyl phenol 5g″ could not transfer to para-aminated product 5g under standard reaction conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We could not detect any desired product and most of the starting material was recovered when N-methyl-substituted phenoxyacetamide (1w) was used under the S/Se-mediated reaction conditions, indicating the indispensable role of the N–H bond (Supplementary Fig. 1b). When compounds 1a and d8-1a were used as substrates under S-mediated reaction conditions, the HRMS data showed that the para amide transfer via an intramolecular pathway and the mixed acetamide migration products were not detected. In addition, a crossover experiment was carried out between equimolar amount of 1a and d8-1a under Se-catalysed reaction conditions in one reactor. Only the intramolecular amides transformation of phenols (2a, d7-2a) were obtained (Supplementary Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 13).

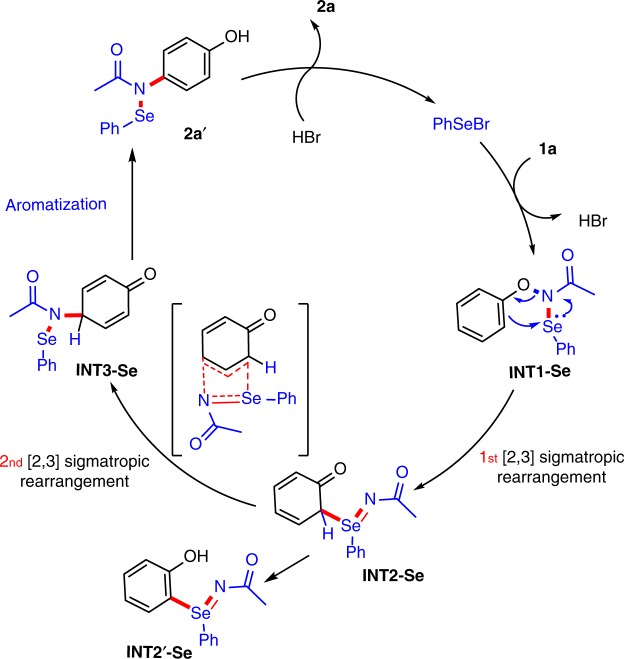

Based on the preliminary studies, the mechanism of this organoselenium-catalysed para-selective C–H bond amination is proposed in Fig. 2. The electrophilic Se species could react with the mildly basic N-phenoxyacetamide 1a to give the Se–N intermediate (INT1-Se) together with the release of one molecule of HBr. Then, the INT1-Se undergoes two successive [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements44–49 to generate the para-amination intermediate (INT3-Se), which may readily react with HBr and then rearomatize to the desired product 2a (for details see Supplementary Figs 4–11).

Fig. 2.

Proposed catalytic cycle of the organoselenium-catalysed para-amination of phenols. A plausible mechanism illustrating how 2a is formed via two consecutive [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements

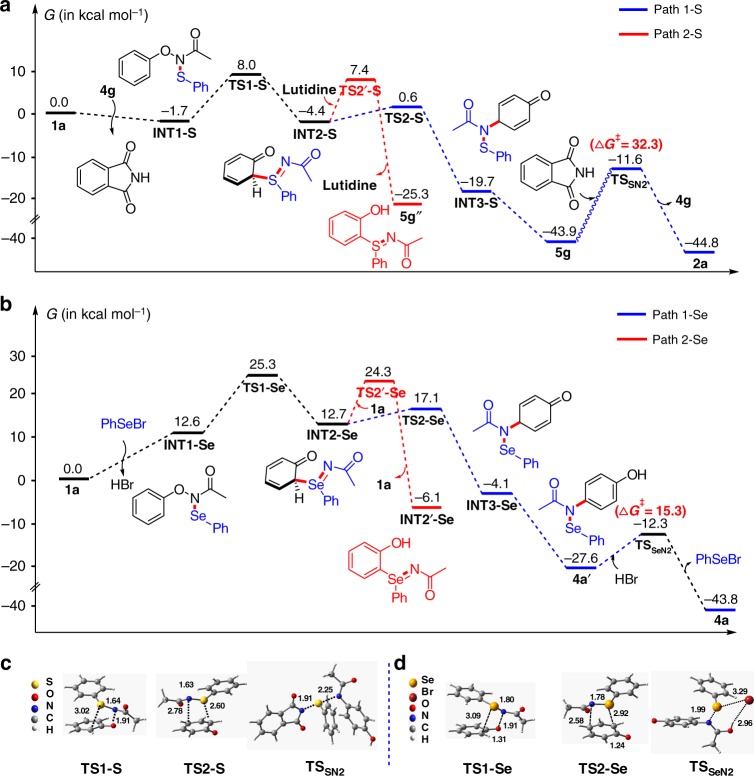

DFT calculations

We performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to explore the mechanistic details for these S (and Se)-mediated para-selective nitrogen migration of N-aryloxyacetamides (Fig. 3). All calculations were carried out with the B3LYP functional50,51, augmented with Grimmes D3 dispersion correction52,53, which already proved to be a good choice for chalcogen-containing systems54,55. For S-mediated reaction, the reaction between N-phenoxyacetamide 1a and N-phenylthiophthalimide 4g was used as model reaction. The Gibbs energy profile is shown in Fig. 3a. First, the reaction of N-phenylthiophthalimide 4g and 1a generates the S–N intermediate INT1-S. Then, the [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of INT1-S via TS1-S forms an ortho-S = N substituted dearomatized species INT2-S, with a barrier of 9.7 kcal mol−1. Subsequently, the second [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of INT2-S yields the para-amination intermediate INT3-S via TS2-S (with a barrier of 5.0 kcal mol−1, see path 1-S). Finally, the aromatization of INT3-S generates the desired product 5g. The whole process is exothermic by 43.9 kcal mol−1, which indicates that the formation of 5g is reasonable. However, the barrier for the regeneration of N-phenylthiophthalimide 4g (via TSSN2) is up to 32.3 kcal mol−1, suggesting the turnover of 4g is difficult even under basic condition. Therefore, for S-mediated reactions, a stoichiometric amount of N-phenylthiophthalimide is required (see Supplementary Fig. 8 for details). For the Se-catalysed reaction, the Gibbs energy profile of the reaction of 1a and PhSeBr is shown in Fig. 3b. Although the reaction of PhSeBr and 1a generating the Se–N intermediate INT1-Se is endothermic by 12.6 kcal mol−1, INT1-Se may readily undergo a Se-centred [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement to generate an ortho-Se = N substituted dearomatized species (INT2-Se) via TS1-Se, with a barrier of 12.7 kcal mol−1. Then, another N-centred [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of INT2-Se forms para-amination intermediate INT3-Se via TS2-Se (with a barrier of 4.4 kcal mol−1, see path 1-Se). Rearomatization of INT3-Se and regeneration of the active catalyst (PhSeBr) from 2a′ affords product 2a readily with large Gibbs energy-driven forces (23.5 and 16.2 kcal mol−1, respectively). In contrast to N-phenylthiophthalimide, the regeneration of PhSeBr is strongly exothermic by 14.7 kcal mol−1 with a barrier of only 15.3 kcal mol−1 (for details see Supplementary Fig. 11). Therefore, PhSeBr could be used as a catalyst. In addition to path 1, the direct rearomatization of INT2 via TS2′ to generate the ortho-S/Se = N substituted phenol (INT2′) is also possible (see path 2-S in Fig. 3a and path 2-Se in Fig. 3b). However, the activation barriers of path 2 in these two systems are much higher than that of path 1. The calculated trends for the two reactions are consistent with the fact that no ortho-Se = N substituted phenol (or only small amount of ortho-S = N substituted phenol) was obtained for these two types of reactions. Therefore, path 1 involving two successive [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements is mainly responsible for the two para-selective amination reactions (for details see Supplementary Figs 2–11 and Supplementary Data 1).

Fig. 3.

Computational studies on S (and Se)-mediated para-selective nitrogen migration of N-phenoxyacetamide (1a). a Computed Gibbs energy profile for S-mediated reaction (in TFE). b Computed Gibbs energy profile for Se-catalysed reaction (in 1,4-dioxane). c Transition states involved in S-mediated reaction. d Transition states involved in Se-catalysed condition

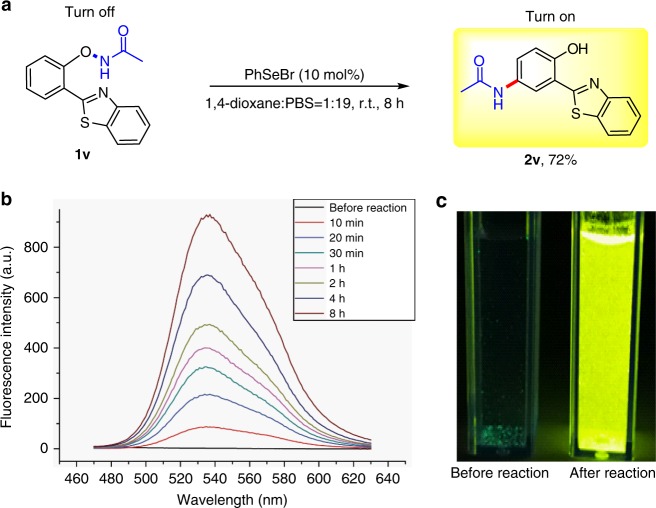

Synthetic application

To further explore the mild nature of our method, an HBT-substrate 1v was subjected to the reaction condition in a mixed solvent of 95% PBS buffer and 5% 1,4-dioxane (Fig. 4a). The obtained product 2v exhibits significant aggregation-induced emission behaviours56–60. The fluorescence intensity of the product increased gradually at 538 nm (Fig. 4b) in the reaction solution, accompanied by a dramatic change in emission colour from pale blue to bright yellow (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Application of the Se-catalysed reaction in aqueous conditions. a Conditions: 1v (0.1 mmol), PhSeBr (10 mol%), DMSO/PBS buffer = 1:19 (4.0 mL); at ambient temperature for 8 h; the yield was isolated yield. b Fluorescence spectra of reaction in aqueous conditions, λex = 380 nm. c Visual fluorescence of the reaction mixture under a 365 nm ultraviolet lamp

Discussion

In summary, we discovered an organoselenium-catalysed para-amination of phenols or dienones under mild conditions. The methodology features a broad substrate scope and a high para-selectivity. More importantly, this work reveals a significant difference between the sulfenylation reagents and organoselenium reagents. While experimental and computational studies suggest that both the sulfur and selenium variants proceed through a double [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, the sulfenylation reagents behave as coupling partners while organoselenium reagents can be employed catalytically. Because of the larger atomic radius of selenium compared to sulfur, selenium is more polarizable (“softer”) than sulfur, allowing intrinsic selenium to be more nucleophilic and electrophilic61,62. Compared to sulfur, the larger hybridized orbitals of selenium results in weaker σ overlap63. So most bond strength of Se−X is weaker. The differences between sulfur and selenium developed here are reminiscent of their behaviours in biology. For example, the catalytic activity of the native enzyme dramatically reduces when the Sec residue in the type I ID enzyme was replaced by a cysteine (Cys) moiety64,65. We expect our present work to stimulate future studies of selenium as an alternative catalytic platform to transition metal-catalysed C–H amination reactions.

Methods

Materials

For NMR spectra of compounds in this manuscript, see Supplementary Figs 14–73. For the crystallographic data of compound 2n and 5a, see Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Tables 3–15. For the representative experimental procedures and analytic data of compounds synthesized, see Supplementary Methods.

Se-catalysed standard reaction conditions

N-phenoxyamides (1) (0.20 mmol), PhSeBr (10 mol%), were weighed into a 10 mL tube, to which was added 1,4-dioxane (2.0 mL). The reaction vessel was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. Then the mixture was concentrated under vacuum and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with a gradient eluent of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate to afford the corresponding product 2 or 3.

S-mediated standard reaction conditions

N-phenoxyacetamides (1) (0.20 mmol), N-substituted thiophthalimides (4) (0.24 mmol) and 2,6-lutidine (1.0 eq.) were weighed into a 10 mL tube, to which was added TFE (2.0 mL). The reaction vessel was stirred at room temperature for 5 h in air. The mixture was then concentrated under vacuum and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with a gradient eluent of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate to afford the corresponding product (5).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the National Science Foundation of China (21622103, 21333004 and 21571098), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20160022) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 020514380117 and No. 020814380002).

Author contributions

D.Y. and F.X. carried out the experimental work. The computational work was conducted by G.W.; D.Y. and G.W. prepared most of the manuscript and supporting information. J.Z., S.L., Z.S., Y.L. and W.-Y.S. guided the research.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1570955 and CCDC1549814. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Dingyuan Yan, Guoqiang Wang, Feng Xiong.

Contributor Information

Yi Lu, Email: luyi@nju.edu.cn.

Shuhua Li, Email: shuhua@nju.edu.cn.

Jing Zhao, Email: jingzhao@nju.edu.cn.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06763-4.

References

- 1.Berzelius JJ. Afh. Fys. Kemi Mineral. 1818;6:42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böck A, et al. Selenocysteine: the 21st amino acid. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:515–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stadtman TC. Selenocysteine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:83–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mousa R, Notis Dardashti R, Metanis N. Selenium and selenocysteine in protein chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:15818–15827. doi: 10.1002/anie.201706876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotruck JT, et al. Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science. 1973;179:588–590. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4073.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K, Avissar N, Whitin J, Cohen H. Purification and characterization of human plasma glutathione peroxidase: a selenoglycoprotein distinct from the known cellular enzyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987;256:677–686. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90624-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamura T, Stadtman TC. A new selenoprotein from human lung adenocarcinoma cells: purification, properties, and thioredoxin reductase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1006–1011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SR, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a mitochondrial selenocysteine-containing thioredoxin reductase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:4722–4734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lescure A, Gautheret D, Carbon P, Krol A. Novel selenoproteins identified in silico and in vivo by using a conserved RNA structural motif. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:38147–38154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthur JR, Nicol F, Beckett GJ. Hepatic iodothyronine 5’-deiodinase. The role of selenium. Biochem. J. 1990;272:537. doi: 10.1042/bj2720537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behne D, Kyriakopoulos A, Meinhold H, Köhrle J. Identification of type I iodothyronine 5’-deiodinase as a selenoenzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;173:1143–1149. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(05)80905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mugesh G, Singh HB. Synthetic organoselenium compounds as antioxidants: glutathione peroxidase activity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2000;29:347–357. doi: 10.1039/a908114c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhabak KP, Mugesh G. Functional mimics of glutathione peroxidase: bioinspired synthetic antioxidants. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1408–1419. doi: 10.1021/ar100059g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wirth T. Small organoselenium compounds: more than just glutathione peroxidase mimics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:10074–10076. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhowmick D, Srivastava S, D’Silva P, Mugesh G. Highly efficient glutathione peroxidase and peroxiredoxin mimetics protect mammalian cells against oxidative damage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:8449–8453. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freudendahl DM, Shahzad SA, Wirth T. Recent advances in organoselenium chemistry. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009;11:1649–1664. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200801171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freudendahl DM, Santoro S, Shahzad SA, Santi C, Wirth T. Green chemistry with selenium reagents: development of efficient catalytic reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:8409–8411. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santi C, Santoro S, Battistelli B. Organoselenium compounds as catalysts in nature and laboratory. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010;14:2442–2462. doi: 10.2174/138527210793358231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kratzschmar F, Kassel M, Delony D, Breder A. Selenium-catalysed C(sp3)−H acyloxylation: application in the expedient synthesis of isobenzofuranones. Chem. Eur. J. 2015;21:7030–7034. doi: 10.1002/chem.201406290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortgies S, Breder A. Selenium-catalysed oxidative C(sp2)−H amination of alkenes exemplified in the expedient aynthesis of (aza-)indoles. Org. Lett. 2015;17:2748–2751. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortgies S, Depken C, Breder A. Oxidative allylic esterification of alkenes by cooperative selenium-catalysis using air as the sole oxidant. Org. Lett. 2016;18:2856–2859. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh FV, Wirth T. Selenium-catalysed regioselective cyclization of unsaturated carboxylic acids using hypervalent iodine oxidants. Org. Lett. 2011;13:6504–6507. doi: 10.1021/ol202800k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Browne DM, Niyomura O, Wirth T. Catalytic use of selenium electrophiles in cyclizations. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3169–3171. doi: 10.1021/ol071223y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahzad SA, Venin C, Wirth T. Diselenide- and disulfide-mediated synthesis of isocoumarins. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010;2010:3465–3472. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201000308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denmark SE, Kornfilt DJ, Vogler T. Catalytic asymmetric thio functionalisation of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15308–15311. doi: 10.1021/ja2064395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cresswell AJ, Eey ST, Denmark SE. Catalytic, stereospecific syn-dichlorination of alkenes. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:146–152. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen F, Tan CK, Yeung YY. C2-symmetric cyclic selenium-catalysed enantioselective bromoaminocyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:1232–1235. doi: 10.1021/ja311202e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao L, Zhang H, Zhao X. Selenium-π-acid catalysed oxidative functionalisation of alkynes: facile access to ynones and multisubstituted oxazoles. ACS Catal. 2018;8:6745–6750. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, An R, Zhang X, Luo J, Zhao X. Enantioselective trifluoromethylthiolating lactonization catalysed by an indane-based chiral sulfide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:5846–5850. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo J, Cao Q, Cao X, Zhao X. Selenide-catalysed enantioselective synthesis of trifluoromethylthiolated tetrahydronaphthalenes by merging desymmetrization and trifluoromethylthiolation. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:527. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02955-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Liang Y, Ji J, Luo J, Zhao X. Chiral selenide-catalysed enantioselective allylic reaction and intermolecular di functionalisation of alkenes: efficient construction of C-SCF3 stereogenic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:4782–4786. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b01513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breder A. Oxidative allylic amination reactions of unactivated olefins–at the frontiers of palladium and selenium catalysis. Synlett. 2014;25:899–904. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1340625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng Z, Wei J, Liao L, Huang H, Zhao X. Organoselenium-catalysed, hydroxy-controlled regio- and stereoselective amination of terminal alkenes: efficient synthesis of 3-amino allylic alcohols. Org. Lett. 2015;17:1834–1837. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X, Guo R, Zhao X. Organoselenium-catalysed synthesis of indoles through intramolecular C–H amination. Org. Chem. Front. 2015;2:1334–1337. doi: 10.1039/C5QO00179J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trenner J, Depken C, Weber T, Breder A. Direct oxidative allylic and vinylic amination of alkenes through selenium catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8952–8956. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liao L, Guo R, Zhao X. Organoselenium-catalysed regioselective C−H pyridination of 1,3-dienes and alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:3201–3205. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prasad CD, et al. Transition-metal-free synthesis of unsymmetrical diaryl chalcogenides from arenes and diaryl dichalcogenides. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:1434–1443. doi: 10.1021/jo302480j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva LT, et al. Solvent- and metal-free chalcogenation of bicyclic arenes using I2/DMSO as non-metallic catalytic system. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017;2017:4740–4748. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201700744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breder A, Ortgies S. Recent developments in sulphur- and selenium-catalysed oxidative and isohypsic functionalisation reactions of alkenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:2843–2852. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denmark SE, Beutner GL. Lewis base catalysis in organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1560–1638. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denmark SE, Collins WR, Cullen MD. Observation of direct sulfenium and selenenium group transfer from thiiranium and seleniranium ions to alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3490–3492. doi: 10.1021/ja900187y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denmark SE, Kalyani D, Collins WR. Preparative and mechanistic studies toward the rational development of catalytic, enantioselective selenoetherification reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15752–15765. doi: 10.1021/ja106837b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denmark SE, Burk MT. Lewis base catalysis of bromo- and iodolactonization, and cycloetherification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20655–20660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005296107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reich HJ. Functional group manipulation using organoselenium reagents. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979;12:22–30. doi: 10.1021/ar50133a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu WM, He J, Yu MQ, Shen GX. Site-selective modification of Vitamin D analogue (Deltanoid) through a resin-based version of organoselenium 2,3-sigmatropic rearrangement. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4431–4433. doi: 10.1021/ol101879k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hans JR. Functional group manipulation using organoselenium reagents. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979;12:22–30. doi: 10.1021/ar50133a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fankhauser JE, Peevey RM, Hopkins PB. Synthesis of protected allylic amines from allylic phenyl selenides: improved conditions for the chloramine T oxidation of allylic phenyl selenides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:15–18. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)91136-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shea RG, et al. Allylic selenides in organic synthesis: new methods for the synthesis of allylic amines. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:5243–5252. doi: 10.1021/jo00376a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurose N, Takahashi T, Koizumi T. Asymmetric [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of chiral sllylic selenimides. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:2932–2933. doi: 10.1021/jo960287b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becke AD. Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. Exch. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle−Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grimme S, Antony J, Ehrlich S, Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132:154104–154119. doi: 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimme S, Hansen A, Brandenburg JG, Bannwarth C. Dispersion-corrected mean-field electronic structure methods. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:5105–5154. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bleiholder C, Werz DB, Köppel H, Gleiter R. Theoretical investigations on chalcogen−chalcogen interactions: what makes these nonbonded interactions bonding? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2666–2674. doi: 10.1021/ja056827g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gleiter R, Haberhauer G, Werz DB, Rominger F, Bleiholder C. From noncovalent chalcogen-chalcogen interactions to supramolecular aggregates: experiments and calculations. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:2010–2041. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mei J, Leung NL, Kwok RT, Lam JW, Tang BZ. Aggregation-induced emission: together we shine, united we soar! Chem. Rev. 2015;115:11718–11940. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu R, Leung NL, Tang BZ. AIE macromolecules: syntheses, structures and functionalities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:4494–4562. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00044G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qian Y, et al. Aggregation-induced emission enhancement of 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole-based excited-state intramolecular proton-transfer compounds. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:5861–5868. doi: 10.1021/jp070076i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qian Y, et al. Restriction of photoinduced twisted intramolecular charge transfer. Chemphyschem. 2010;12:397–404. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai M, et al. A small change in molecular structure, a big difference in the AIEE mechanism. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012;14:5289–5296. doi: 10.1039/c2cp23040b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steinmann D, Nauser T, Koppenol WH. Selenium and sulphur in exchange reactions: a comparative study. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:6696–6699. doi: 10.1021/jo1011569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trofymchuk OS, Zheng Z, Kurogi T, Mindiola DJ, Walsh PJ. Selenolate anion as an organocatalyst: reactions and mechanistic studies. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018;360:1685–1692. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201701568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reich HJ, Hondal RJ. Why nature chose selenium. Acs. Chem. Biol. 2016;11:821–841. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berry MJ, Kieffer JD, Harney JW, Larsen PR. Selenocysteine confers the biochemical properties characteristic of the type I iodothyronine deiodinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:14155–14158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larsen PR, Berry MJ. Nutritional and hormonal regulation of thyroid hormone deiodinases. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1995;15:323–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1570955 and CCDC1549814. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.