Abstract

Light attenuation in thick biological tissues, caused by a combination of absorption and scattering, limits the penetration depth in multiphoton microscopy (MPM). Both tissue scattering and absorption are dependent on wavelengths, which makes it essential to choose the excitation wavelength with minimum attenuation for deep imaging. Although theoretical models have been established to predict the wavelength dependence of light attenuation in brain tissues, the accuracy of these models in experimental settings needs to be verified. Furthermore, the water absorption contribution to the tissue attenuation, especially at 1450 nm where strong water absorption is predicted to be the dominant contributor in light attenuation, has not been confirmed. Here we performed a systematic study of in vivo three-photon imaging at different excitation wavelengths, 1300 nm, 1450 nm, 1500 nm, 1550 nm, and 1700 nm, and quantified the tissue attenuation by calculating the effective attenuation length at each wavelength. The experimental data show that the effective attenuation length at 1450 nm is significantly shorter than that at 1300 nm or 1700 nm. Our results provide unequivocal validation of the theoretical estimations based on water absorption and tissue scattering in predicting the effective attenuation lengths for long wavelength in vivo imaging.

OCIS codes: (180.4315) Nonlinear microscopy, (170.3880) Medical and biological imaging

1. Introduction

Multiphoton microscopy (MPM) enables deep imaging in highly scattering biological tissues due to the use of nonlinear excitation and long excitation wavelengths [1–4]. It has been demonstrated that the multiphoton excited fluorescence signal within the focal volume is mostly generated by ballistic photons (photons that maintain their ballistic trajectories). When imaging deep in scattering biological samples such as the mouse brain, the number of ballistic photons arriving at the focus is significantly reduced due to the absorption and scattering by the tissue [5, 6], characterized by the effective attenuation length (EAL). The ballistic photons as a function of depth (z) can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where Pz is the optical power at the focus, P0 is the optical power on the sample surface, and le is the EAL.

The loss of ballistic photons reduces the fluorescence generation. In order to obtain sufficient signal from the focus, the exponential decay of the excitation light needs to be compensated by increasing the total optical power at the surface. Obviously, with the same excitation power, less tissue attenuation (or longer EAL) will allow for deeper tissue penetration [7].

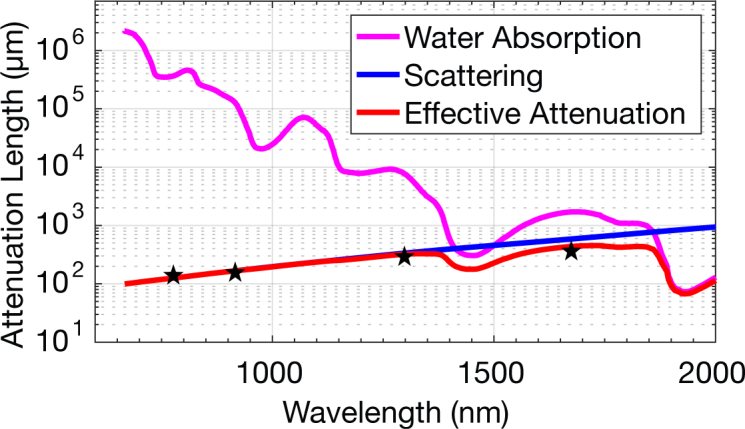

Light attenuation in biological tissues is a combined effect of absorption and scattering. Using mouse brain tissue in vivo as an example, at wavelengths between 700 nm and 1060 nm—the wavelength tuning range of the mode-locked Ti:S laser—attenuation of the excitation light is completely dominated by tissue scattering [8], while the absorption (mostly by blood for in vivo imaging) is relatively low [9–11]. Longer wavelengths at approximately 1200 nm–1850 nm are advantageous for deep brain imaging due to the reduction of light scattering. However, water absorption (water content is >70% in brain tissues [12]) increases significantly in this spectral region and becomes the dominant absorber for in vivo imaging. Both water absorption and tissue scattering contribute to the attenuation of the excitation light, therefore, the optimum choice of the excitation wavelength is a trade-off between these two factors. The theoretical model of calculating le (Fig. 1) is then [3]:

| (2) |

where la is the water absorption length [13], and ls is the scattering mean-free path, calculated using Mie scattering for a tissue-like colloidal solution containing 1-µm diameter beads at a concentration of 5.4×109 beads/mL [14–16].

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of the effective attenuation lengths based on water absorption and Mie scattering. The black stars indicate the reported effective attenuation lengths in mouse brains in vivo, 131 µm at 775 nm [17], 152∼158 µm at 920 nm [18], 305 ~ 319 µm at 1300 nm [18] and 383 µm at 1680 nm [3].

Theoretical estimations based on tissue absorption and scattering predict that the longer excitation wavelength approach is advantageous for deeper tissue imaging (Fig. 1), and previous experimental works have shown that the longer wavelength windows of 1300 nm [17–22] and 1700 nm [3, 22] outperform the shorter wavelengths, such as 775 nm [17], 800 nm [19, 23], 830 nm [24, 25], 920 nm [14, 18, 26], by a factor of 2 to 3 times in terms of imaging depth. However, the attenuation at these wavelengths are all dominated by scattering (i.e., la is at least several times larger than ls). As previous experimental data all lie close to the scattering curve (the blue line in Fig. 1), it indicates that scattering alone, without any consideration of the absorption, would have predicted similar wavelength dependence. In particular, the absorption-scattering model predicts that the long wavelength window is not one continuous window. Instead, it indicates that there are two windows for mouse brain imaging centered at ∼ 1300 nm and 1700 nm, with a gap at ∼ 1450 nm due to strong water absorption (Fig. 1). In this paper, we compared the effective attenuation lengths at the excitation wavelengths of 1300 nm, 1450 nm, 1500 nm, 1550 nm, and 1700 nm in mouse brains in vivo. Our results confirm the existence of the water absorption feature in the wavelength dependence of EAL, and provide unequivocal support for the absorption-scattering model for ballistic photon penetration.

2. Characterization of the excitation source at 1700 nm, 1550 nm, 1500 nm, and 1450 nm

The three-photon imaging setup is similar to that described previously [3, 4]. The excitation source was a wavelength-tunable optical parametric amplifier (OPA, Opera-F, Coherent) pumped by a Monaco amplifier (Coherent) operating at 330 kHz repetition rate. The excitation pulse spectra at 1700 nm, 1550 nm, 1500 nm, and 1450 nm were measured by an Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA, Thorlabs), shown in Fig. 2(a).

Fig. 2.

(a) Measured spectra of the laser source operating at 1700 nm, 1550 nm, 1500 nm, 1450 nm and 1300 nm. Dependence of three-photon-excited fluorescence on excitation power for (b) 1700 nm and (c) 1450 nm in logarithmic scales. The blue diamonds are the measured data, and the red lines are linear fits to the experimental results. The slope is indicated in each figure.

We measured the dependence of the fluorescence from Texas Red on the excitation power at 1700 nm and 1450 nm to ensure three-photon excitation (Figs. 2(b) and 2(c)). The generated fluorescence was detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT) with a GaAsP photocathode (H7422-40, Hamamatsu Photonics), and recorded by a photon counter (SR400, Stanford Research Systems). The slopes in the log-log plots confirmed three-photon excitation for Texas Red at both 1700 nm and 1450 nm.

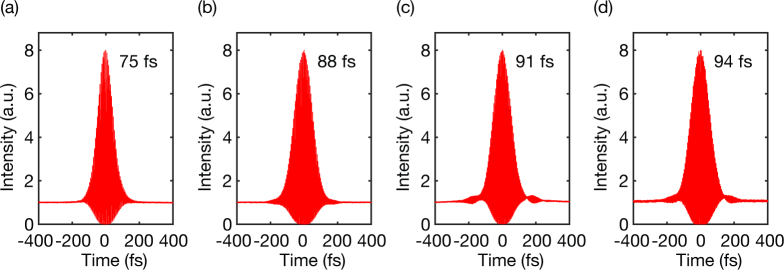

Dispersion from the optics in the microscope were pre-compensated using a Si wafer (Edmund Optics) placed at the Brewster angle [27]. Second-order interferometric autocorrelations were performed after the objective lens at each wavelength (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Measured second-order interferometric autocorrelations of the laser pulse operating at (a) 1700 nm, (b) 1550 nm, (c) 1500 nm, and (d) 1450 nm. The intensity full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the pulse is indicated in each figure, assuming a deconvolution factor of 1.54 for sech2-pulse.

The excitation beam size at the back aperture of the objective lens impacts the measurements of the EALs, since the marginal rays have longer path lengths in the tissue and experience more attenuation than the chief rays at the center of the lens. To ensure there is no systematic bias in the EAL measurements, we characterized the beam size at each excitation wavelength (Fig. 4) using a calibrated InGaAs camera (Axiom Optics, WiDy SWIR 640). The measurements were taken before the scanner and there is a 6x magnification from the scan mirrors to the back aperture of the objective lens. The beam size variation at these wavelengths is below 6%, which has negligible impact on the EAL measurements [28].

Fig. 4.

Beam size measurements at (a) 1700 nm, (b) 1550 nm, (c) 1500 nm, and (d) 1450 nm. The blue dots are the measured data, and the red lines are Gaussian fits to the measurements. There is some ellipticity in the excitation beam, therefore the measurements were taken along both the long axis (left) and the short axis (right). The FWHM is labeled in each figure.

3. In vivo EAL measurements at 1700 nm, 1550 nm, 1500 nm, and 1450 nm excitation wavelengths

A craniotomy was performed on a 10-week-old wild-type mouse (C57BL/6J) and a glass window was placed directly on the intact dura for imaging. The mouse was anesthetized using isoflurane (3% in oxygen for induction and 1.5–2% for surgery and imaging to maintain a breathing frequency of 1 Hz). Body temperature was kept at 37.5 °C with a feedback-controlled blanket (Harvard Apparatus), and eye ointment was applied. Dextran-conjugated Texas Red (70kDa, Invitrogen) was injected retro-orbitally for the brain vasculature labeling prior to imaging.

Three-photon imaging was performed in the same intact brain using four different excitation wavelengths, in the order of 1700 nm, 1550 nm, 1500 nm, 1450 nm, and 1700 nm. The 1700 nm excitation was repeated again at the end of the imaging session to ensure that the imaging sequence did not impact the measurements. All imaging were done using the same fluorophore in the same brain regions within the same mouse, which eliminated the uncertainty caused by the emission-wavelength difference and tissue-to-tissue variation. All images were taken at a frame rate of 0.24 Hz (512 × 512 pixels/frame) with a field of view (FOV) of 340 × 340 µm, and 10 frames were averaged at each depth. The detection path was kept the same for all the wavelengths in this comparison. Thus, the differences in the EALs were only due to the different excitation wavelengths used.

We acquired approximately 1-mm-deep z-stack, taken at 10-µm depth increment. To avoid potential tissue heating, especially at 1450 nm due to the high water absorption, we kept the maximum average power on the brain surface at 35 mW for all the excitation wavelengths used. Power curves (dependence of the signal value on excitation power) were measured to ensure that no fluorophore saturation (i.e., ground state depletion) occurred at any imaging depth.

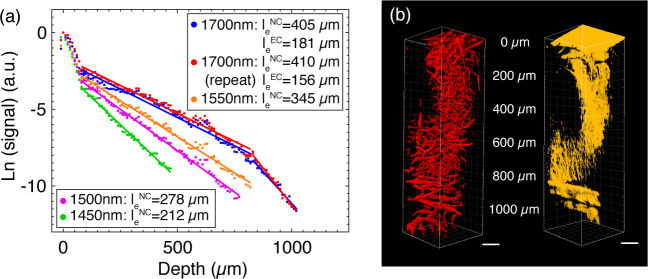

The fluorescence signal generated in three-photon microscopy (F3P) is proportional to power cubic [29]. Combining Eq. (1), we have:

| (3) |

We selected the average value of the brightest 1% of pixels in the x-y image at each depth as the fluorescence signal. In three-photon microscopy (3PM), EAL is defined as the depth at which the normalized signal attenuates by 1/e3. By plotting the fluorescence signal as a function of depth, the EALs can be obtained from the slopes of the linear fits in Fig. 5(a) for the neocortex (NC, 0–840 µm) and the external capsule (EC, 840–1040 µm), assuming the vasculature was labeled homogenously throughout the imaging regions. Measured EALs in the NC at different wavelengths with an uncertainty estimation based on the 95% confidence interval (CI) are: 391∼418 µm at 1700 nm, 337∼353 µm at 1550 nm, 272 ~ 283 µm at 1500 nm, 207 ~ 218 µm at 1450 nm, and 398 ∼ 422 µm at 1700 nm (repeat experiment).

Fig. 5.

(a) Comparison of the fluorescence signal as a function of depth at 1700 nm, 1550 nm, 1500 nm, 1450 nm, and 1700 nm (repeat experiment). The dots are the measured data, and the lines are linear fits to the measurements. With the same maximum average power, imaging at 1700 nm excitation includes both the neocortex (NC) and external capsule (EC), while imaging using the other wavelengths is limited to the NC. (b) 3D reconstruction of three-photon images of Texas Red-labeled brain vasculature, left, fluorescence, right, third harmonic generation (THG). Imaging depths are labeled in the middle. Scale bars, 100 µm.

To ensure that the results are not dependent on the selection criteria for the brightest pixels, we varied the selection criteria, and found that this variation did not affect the EAL measurements significantly. Taking the neocortex images acquired at 1700 nm as an example, we selected 0.5% (le=400 µm, 386∼414 µm with 95% CI), 1% (le=405 µm, 391 ~ 418 µm with 95% CI), 1.5% (le=408 µm, 394∼423 µm with 95% CI) and 2% (le=410 µm, 396 ∼ 426 µm with 95% CI) of the brightest pixels. With all the selection criteria between 0.5% and 2%, the resulting EALs vary by ∼ 2.5%, which will have no impact on the conclusion of this paper.

We also reconstructed the images from all depths for both fluorescence signal and third harmonic generation (THG) signal. The dense myelin layer in the external capsule (EC) generates strong THG, which allows us to delineate the neocortex and the external capsule (Fig. 5(b)). Although blood is assumed to be homogeneously distributed within the brain region, the presence of a large blood vessel at the brain surface (see Fig. 6(a)) results in the steeper slope at the beginning of each decay curve (Fig. 5(a), 0–80 µm). Since the brightest pixels are all within this large vessel, the fluorescence signal decays rapidly, reflecting the fact that the attenuation length for blood is much shorter than that of the brain tissue. The measured EALs within this large vessel (0–80 µm, top 1% brightest pixels represented as signal) are: 117 µm at 1700 nm (97~137 µm with 95% CI), 89 µm at 1550 nm (80∼98 µm with 95% CI), 81 µm at 1500 nm (76~87 µm with 95% CI), 68 µm at 1450 nm (65∼72 µm with 95% CI), and 112 µm at 1700 nm (repeat experiment, 88~136 μm with 95% CI).

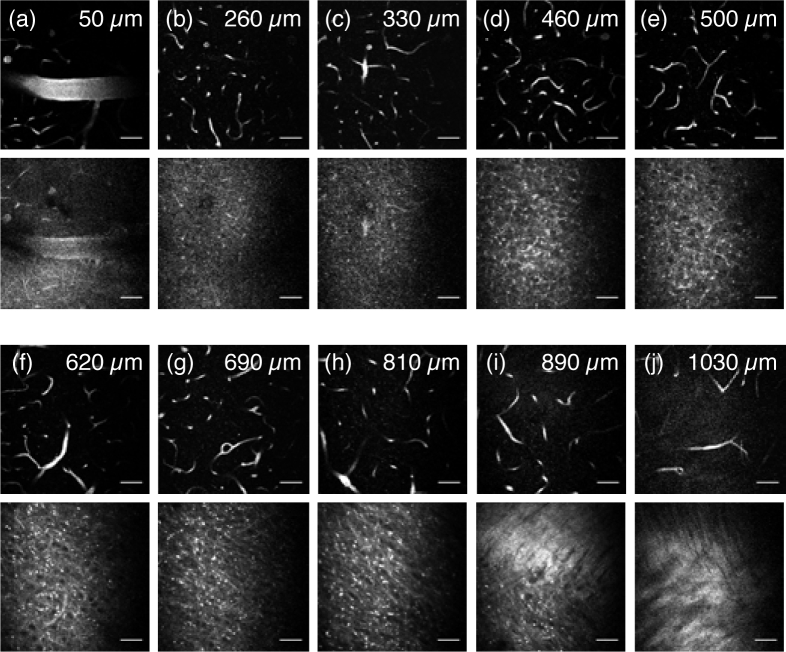

Fig. 6.

Three-photon fluorescence images of the brain vasculature (upper) and THG images (lower) using 1700 nm excitation. The depths are indicated in the images. All the images are shown with the same contrast setting with the brightest 1% pixels saturated. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Similar measurements were repeated on different mice. The absolute EAL values varied somewhat among the different mice, which could be caused by variations in the surgical preparation or the individuality of the mice. Nonetheless, the relative trend of the EALs, i.e., le (1700 nm) > le (1550 nm) > le (1500 nm) > le (1450 nm), holds for all the mice. Three of them are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of in vivo EAL measurements of the neocortex (NC) in three mice

| Mouse | 1700 nm | 1550 nm | 1500 nm | 1450 nm | 1700 nm (repeat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse1 | 405 µm | 319 µm | 278 µm | 212 µm | 410 µm |

| Mouse 2 | 350 µm | 257 µm | 220 µm | 173 µm | 348 µm |

| Mouse 3 | 370 µm | 283 µm | 241 µm | 188 µm | 370 µm |

4. In vivo EAL measurements at 1300 nm and 1450 nm excitation wavelengths

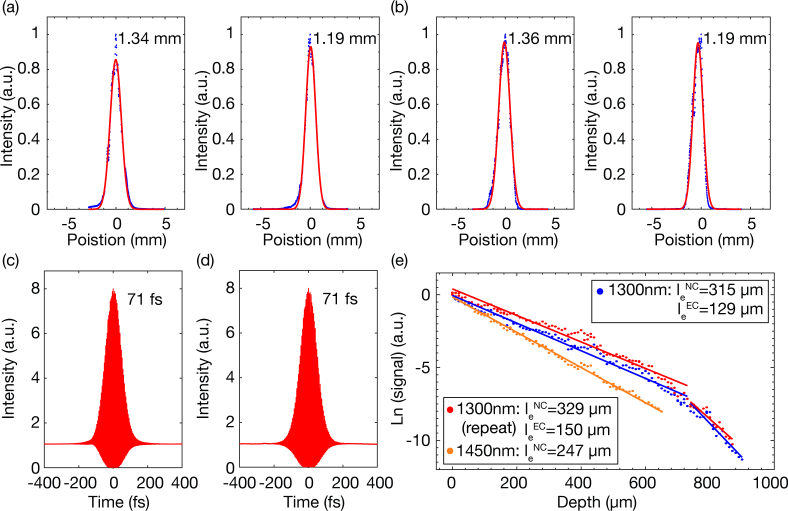

In order to verify the contribution of water absorption in tissue attenuation at 1450 nm, we performed an additional comparison experiment of EAL measurements at 1300 nm and 1450 nm excitation wavelengths. The laser spectra at 1300 nm and 1450 nm are shown in Fig. 2(a). The beam sizes at both excitation wavelengths were measured before the scanner (Figs. 7(a) and 7(b)), with differences less than 1.5%. Second-order interferometric autocorrelations were performed after the objective lens at both wavelengths (Figs. 7(c) and 7(d)). The characterization method was the same as described in Section 2.

Fig. 7.

Beam size measurements at (a) 1300 nm and (b) 1450 nm. The blue dots are the measured data, and the red lines are Gaussian fits to the measurements. Measurements were taken along both the long axis (left) and the short axis (right). The FWHM is labeled in each figure. Measured second-order interferometric autocorrelations of the laser pulse operating at (c) 1300 nm and (d) 1450 nm. The FWHM of the pulse is indicated in the figure, assuming a deconvolution factor of 1.54 for sech2-pulse. (e) Comparison of the fluorescence signal as a function of depth at 1300 nm, 1450 nm, and 1300 nm (repeat experiment). The dots are the measured data, and the lines are linear fits to the measurements. With the same maximum average power, imaging by 1300 nm excitation includes both the NC and EC, while imaging by 1450 nm is limited to the NC.

Because a mixture of 2- and 3-photon fluorescence from Texas Red is generated at 1300 nm excitation, we carried out this experiment separately using Fluorescein. Three-photon imaging was performed on the same Fluorescein-labeled (dextran conjugate, 70kDa, Invitrogen) vasculature in an intact mouse brain in vivo in the order of 1300 nm, 1450 nm and 1300 nm (as a repeat). The results are presented in Fig. 7(e) for the neocortex (NC, 0–740 µm) and the external capsule (EC, 740–900 µm). Measured EALs in the NC at different wavelengths with 95% CI are: 304~326 µm at 1300 nm, 243∼251 µm at 1450 nm, 315∼345 µm at 1300 nm (repeat experiment). The results at 1300 nm are consistent with previous studies [17, 18, 21] and are longer than that at 1450 nm. This comparison confirmed that water absorption is a key factor in the tissue attenuation at 1450 nm.

5. Discussion

The average values of the EAL measurements at different wavelengths are plotted together with the theoretical prediction (Fig. 8), indicating a close match between the experiments and theory.

Fig. 8.

Experimental data (averaged from all the measured EALs for each wavelength, black triangles) is shown on the same plot together with the theoretical model, indicating the accuracy of the model at predicting the experimental measurements at these excitation wavelengths.

Measurements of the EAL can be influenced by the excitation beam characteristics. The excitation beam in the experiments with fluorescein is somewhat different (e.g., beam diameter) from that with Texas Red, making the comparison of the EALs at 1450 nm obtained by the imaging results based on Texas Red and Fluorescein difficult. Even more important, there can be variations in the tissue properties or animal preparations (e.g., cranial window implant) when different mice are used. For example, the EALs for three different mice varied by approximately 20% in our measurements at 1450 nm (Table 1), even with the same beam characteristics and the same fluorophore.

Our comparison results confirm that there is less light attenuation at 1300 nm and 1700 nm than at 1450 nm. Although 1300 nm and 1700 nm are optimum in the long wavelength window for in vivo deep tissue multiphoton imaging, the selection between 1300 nm and 1700 nm depends on the imaging applications. There is more tissue attenuation (shorter EAL) at 1300 nm excitation than at 1700 nm; however, 1300 nm has less tissue absorption, which allows for higher excitation power at the brain surface. It is therefore a trade-off between the coefficient (P0) and the exponent (le) in Eq. (1), 1300 nm will be the wavelength of choice for relatively shallow regions and 1700 nm will perform better for pushing the absolute imaging depth, especially when the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) is also taken into account [8]. Estimations based on the measured EALs and the permissible average power show that 1300 nm is more appropriate for imaging in the neocortex, while 1700 nm is perhaps more advantageous for imaging subcortical regions. In addition, the choice of the excitation wavelength certainly depends on the fluorophores. For brain activity imaging, for example, the robust, green fluorescent protein (GFP) based genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) such as GCaMPs [30] dictate the use of 1300 nm excitation, while red fluorescent GECIs (RCaMPs, RGECOs [31]) would require the use of 1700 nm excitation.

6. Conclusion

We performed a systematic study of the impact of different excitation wavelengths on multiphoton imaging of the mouse brain in vivo. By comparing the effective attenuation lengths at 1300 nm, 1450 nm, 1500 nm, 1550 nm, and 1700 nm excitation wavelengths, we experimentally verified the water absorption contribution in brain tissue attenuation, especially at 1450 nm. Our results show that the theoretical estimations based on water absorption and tissue scattering are accurate in predicting tissue attenuation in the long wavelength window. This study can be used as an experimental guide of selecting excitation wavelengths for mouse brain imaging applications. For MPM of mouse brain in vivo, the spectral windows of 1300 nm and 1700 nm are optimum for deep imaging.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NSF DBI-1707312 NeuroNex grant, and supported by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) via Department of Interior/Interior Business Center (DoI/IBC) contract number D16PC00003.

The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright annotation thereon. Disclaimer: The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of IARPA, DoI/IBC, or the U.S. Government.

Funding

National Science Foundation (DBI-1707312); Department of Interior/Interior Business Center (DoI/IBC) (D16PC00003).

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References and links

- 1.Denk W., Strickler J. H., Webb W. W., “Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy,” Science 248, 73–76 (1990). 10.1126/science.2321027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denk W., Svoboda K., “Photon Upmanship: Why Multiphoton Imaging Is More than a Gimmick,” Neuron 18, 351–357 (1997). 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81237-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton N. G., Wang K., Kobat D., Clark C. G., Wise F. W., Schaffer C. B., Xu C., “In vivo three-photon microscopy of subcortical structures within an intact mouse brain,” Nat. Photonics 7, 205–209 (2013). 10.1038/nphoton.2012.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ouzounov D. G., Wang T., Wang M., Feng D. D., Horton N. G., Cruz-Hernández J. C., Cheng Y.-T., Reimer J., Tolias A. S., Nishimura N., Xu C., “In vivo three-photon imaging of activity of GCaMP6-labeled neurons deep in intact mouse brain,” Nat. Methods 14, 388–390 (2017). 10.1038/nmeth.4183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ying J., Liu F., Alfano R. R., “Effect of scattering on nonlinear optical scanning microscopy imaging of highly scattering media,” Appl. Opt. 39, 509–514 (2000). 10.1364/AO.39.000509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn A. K., Wallace V. P., Coleno M., Berns M. W., Tromberg B. J., “Influence of optical properties on two-photon fluorescence imaging in turbid samples,” Appl. Opt. 39, 1194–1201 (2000). 10.1364/AO.39.001194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oheim M., Beaurepaire E., Chaigneau E., Mertz J., Charpak S., “Two-photon microscopy in brain tissue: parameters influencing the imaging depth,” J. Neurosci. Methods 111, 29–37 (2001). 10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00438-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helmchen F., Denk W., “Deep tissue two-photon microscopy,” Nat. Methods 2, 932–940 (2005). 10.1038/nmeth818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roggan A., Friebel M., Doerschel K., Hahn A., Mueller G. J., “Optical properties of circulating human blood in the wavelength range 400–2500 nm,” J. Biomed. Opt 4, 36–47 (1999). 10.1117/1.429919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friebel M., Roggan A., Müller G. J., Meinke M. C., “Determination of optical properties of human blood in the spectral range 250 to 1100 nm using Monte Carlo simulations with hematocrit-dependent effective scattering phase functions,” J. Biomed. Opt 11, 034021 (2006). 10.1117/1.2203659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacques S. L., “Optical properties of biological tissues: a review,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58, R37 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/11/R37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinoso R. F., Telfer B. A., Rowland M., “Tissue water content in rats measured by desiccation,” J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 38, 87–92 (1997). 10.1016/S1056-8719(97)00053-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kou L., “Refractive indices of water and ice in the 0.65- to 2.5-µm spectral range,” Appl. Opt. 32, 3531–3540 (1993). 10.1364/AO.32.003531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theer P., Hasan M. T., Denk W., “Two-photon imaging to a depth of 1000 µm in living brains by use of a Ti:Al2O3 regenerative amplifier,” Opt. Lett. 28, 1022–1024 (2003). 10.1364/OL.28.001022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheong W. F., Prahl S. A., Welch A. J., “A review of the optical properties of biological tissues,” IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 26, 2166–2185 (1990). 10.1109/3.64354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K., Horton N. G., Charan K., Xu C., “Advanced Fiber Soliton Sources for Nonlinear Deep Tissue Imaging in Biophotonics,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 20, 50–60 (2014). 10.1109/JSTQE.2013.2276860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobat D., Durst M. E., Nishimura N., Wong A. W., Schaffer C. B., Xu C., “Deep tissue multiphoton microscopy using longer wavelength excitation,” Opt. Express 17, 13354–13364 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.013354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang T., Ouzounov D., Wang M., Xu C., “Quantitative Comparison of Two-photon and Three-photon Activity Imaging of GCaMP6s-labeled Neurons in vivo in the Mouse Brain,” in “Optics in the Life Sciences Congress (2017), paper BrM4B.4,” (Optical Society of America, 2017), p. BrM4B.4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balu M., “Effect of excitation wavelength on penetration depth in nonlinear optical microscopy of turbid media,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14, 010508 (2009). 10.1117/1.3081544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasan V. J., Radhakrishnan H., Jiang J. Y., Barry S., Cable A. E., “Optical coherence microscopy for deep tissue imaging of the cerebral cortex with intrinsic contrast,” Opt. Express 20, 2220–2239 (2012). 10.1364/OE.20.002220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobat D., Horton N. G., Xu C., “In vivo two-photon microscopy to 1.6-mm depth in mouse cortex,” J. Biomed. Opt 16, 106014 (2011). 10.1117/1.3646209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong S. P., Merkle C. W., Cooke D. F., Zhang T., Radhakrishnan H., Krubitzer L., Srinivasan V. J., “Noninvasive, in vivo imaging of subcortical mouse brain regions with 1.7 µm optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Lett. 40, 4911–4914 (2015). 10.1364/OL.40.004911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoumi A., Yeh A., Tromberg B. J., “Imaging cells and extracellular matrix in vivo by using second-harmonic generation and two-photon excited fluorescence,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 11014–11019 (2002). 10.1073/pnas.172368799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinfeld D., Mitra P. P., Helmchen F., Denk W., “Fluctuations and stimulus-induced changes in blood flow observed in individual capillaries in layers 2 through 4 of rat neocortex,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 15741–15746 (1998). 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinfeld D., Denk W., “Two-photon imaging of neocortical microcirculation,” in Imaging Neurons: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1999), pp. 1–23 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charan K., Li B., Wang M., Lin C. P., Xu C., “Fiber-based tunable repetition rate source for deep tissue two-photon fluorescence microscopy,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 2304–2311 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.002304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horton N. G., Xu C., “Dispersion compensation in three-photon fluorescence microscopy at 1,700 nm,” Biomed. Opt. Express 6, 1392–1397 (2015). 10.1364/BOE.6.001392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang K., Liang R., Qiu P., “Fluorescence Signal Generation Optimization by Optimal Filling of the High Numerical Aperture Objective Lens for High-Order Deep-Tissue Multiphoton Fluorescence Microscopy,” IEEE Photonics J.. 7, 1–8 (2015). 10.1109/JPHOT.2015.2505145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu C., Webb W. W., “Multiphoton excitation of molecular fluorophores and nonlinear laser microscopy,” in Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, vol. 5 (Springer, New York, 1997), pp. 471–540. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen T.-W., Wardill T. J., Sun Y., Pulver S. R., Renninger S. L., Baohan A., Schreiter E. R., Kerr R. A., Orger M. B., Jayaraman V., Looger L. L., Svoboda K., Kim D. S., “Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity,” Nature. 499, 295–300 (2013). 10.1038/nature12354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dana H., Mohar B., Sun Y., Narayan S., Gordus A., Hasseman J. P., Tsegaye G., Holt G. T., Hu A., Walpita D., Patel R., Macklin J. J., Bargmann C. I., Ahrens M. B., Schreiter E. R., Jayaraman V., Looger L. L., Svoboda K., Kim D. S., “Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity,” eLife 5, e12727 (2016). 10.7554/eLife.12727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]