Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy have been associated with a reduced risk for pregnancy loss. However, most prior studies enrolled women with clinically recognized pregnancies, thereby missing early losses.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the association of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy with pregnancy loss.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

A randomized clinical trial, Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction, enrolled women with 1 or 2 prior pregnancy losses at 4 US clinical centers from June 15, 2007, to July 15, 2011. This secondary analysis was limited to women with a pregnancy confirmed by positive results of a human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) test. Nausea symptoms were ascertained from daily preconception and pregnancy diaries for gestational weeks 2 to 8. From weeks 12 to 36, participants completed monthly questionnaires summarizing symptoms for the preceding 4 weeks. A week-level variable included nausea only, nausea with vomiting, or neither.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Peri-implantation (hCG-detected pregnancy without ultrasonographic evidence) and clinically recognized pregnancy losses.

RESULTS

A total of 797 women (mean [SD] age, 28.7 [4.6] years) had an hCG-confirmed pregnancy. Of these, 188 pregnancies (23.6%) ended in loss. At gestational week 2, 73 of 409 women (17.8%) reported nausea without vomiting and 11 of 409 women (2.7%), nausea with vomiting. By week 8, the proportions increased to 254 of 443 women (57.3%) and 118 of 443 women (26.6%), respectively. Hazard ratios (HRs) for nausea (0.50; 95% CI, 0.32–0.80) and nausea with vomiting (0.25; 95% CI, 0.12–0.51) were inversely associated with pregnancy loss. The associations of nausea (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.29–1.20) and nausea with vomiting (HR,0.51; 95% CI, 0.11–2.25) were similar for peri-implantation losses but were not statistically significant. Nausea (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.26–0.74) and nausea with vomiting (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.09–0.44) were associated with a reduced risk for clinical pregnancy loss.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Among women with 1 or 2 prior pregnancy losses, nausea and vomiting were common very early in pregnancy and were associated with a reduced risk for pregnancy loss. These findings overcome prior analytic and design limitations and represent the most definitive data available to date indicating the protective association of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy and the risk for pregnancy loss.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00467363

Nausea with or without vomiting is reported by as many as 80% of women during pregnancy1 and can have a substantial negative effect on quality of life.2 Although speculation commonly suggests that nausea is a good sign and indicative of a healthy pregnancy, evidence supporting this assertion is limited.

Much of the published literature reports on studies that enrolled women after a clinically recognized pregnancy, thereby failing to include women with early pregnancy losses or relying on participant recall of nausea and/or loss.3–8 Thus, in the absence of prospective data, nausea and vomiting may be no more than a sign of still being pregnant as opposed to a sign of the health of the pregnancy. In addition, most prior studies have not considered behavioral factors, such as stress, exercise, and caffeine intake, or fetal characteristics, such as karyotype or the presence of a multiple gestation.

Our objectives in the present study were to describe the natural history of nausea and vomiting symptoms early in pregnancy and to evaluate the association between these symptoms and pregnancy loss. We examined data from a prospective preconception cohort of women who conceived and recorded daily nausea and vomiting symptoms from gestational week 2 (ie, conception) through week 8 and monthly thereafter.

Methods

Study Sample and Procedures

This study was a secondary ad hoc analysis of the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction (EAGeR) trial, a multi-center, block-randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial that examined the effect of preconception low-dose aspirin on pregnancy loss and live birth.9 All women were aged 18 to 40 years, were actively trying to conceive, and had a history of 1 or 2 pregnancy losses (n = 1228). Inclusion and exclusion criteria have been detailed elsewhere.10 Data were collected from June 15, 2007, to July 15, 2011. Women were followed up for as many as 6 menstrual cycles while trying to conceive and through pregnancy if conception was successful. The present analysis was limited to women with a positive result of a human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) pregnancy test.11 The institutional review boards at the University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel; University of Utah, Salt Lake City; and University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York, approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

During the preconception period, women underwent active or passive follow-up (eFigure in the Supplement). Women were in active follow-up during the first 2 menstrual cycles after enrollment. During active follow-up, women completed a preconception daily diary (paper booklet), provided daily urine samples, used a fertility monitor (ClearBlue Easy; Iverness Medical), and completed clinic visits in the middle and at the end of each cycle. Women entered passive follow-up if they did not become pregnant during the first 2 cycles. During passive follow-up, women used the fertility monitor and completed clinic visits at the end of each cycle. After an hCG-positive pregnancy test result, women entered pregnancy follow-up, during which a pregnancy-specific daily diary assessing common pregnancy symptoms and other exposures was completed for 4 weeks. Study ultrasonography was performed during gestational week 6 or 7. We determined gestational age based on ultrasonographic findings. For participants who had a pregnancy loss before ultrasonography could be performed, pregnancy dating was based on the first day of the last menstrual period as recorded with the fertility monitor or the preconception diary. Study clinic visits were performed at weeks 8, 12, 20, and 28 and telephone contact at weeks 16, 24, 32, and 36.

Assessment of Nausea and Vomiting

In their daily preconception and pregnancy diaries, participants rated nausea and vomiting as none, nausea only, vomiting once per day, or vomiting more than once per day. The preconception diary was used to quantify nausea and vomiting from gestational week 2 (ie, conception) until pregnancy was confirmed in the clinic and the pregnancy diary was initiated. All diaries were paper forms that were completed at home and then returned and reviewed by study coordinators at each visit.

From gestational weeks 12 to 36, participants completed monthly questionnaires describing their nausea and vomiting symptoms during the prior 4 weeks as follows: never, rarely (once per month), occasionally (2 or 3 times per month), sometimes (1 or 2 times per week), often (3–6 times per week), or daily. Only participants who remained pregnant at the time of the questionnaire were asked to complete the questionnaire for the preceding 4 weeks, ensuring that all data were prospectively collected before the pregnancy outcome.

For all analyses, daily diary and questionnaire data were summarized into week-level variables. For gestational weeks 2 to 8, if a woman reported having any nausea on any given day during that week, then we considered her to have had nausea during that week; otherwise, we considered her not to have had nausea. Vomiting was treated similarly. For any week with vomiting, we also considered women to have had nausea because the state of nausea precedes vomiting. Nausea and vomiting symptoms ascertained from the monthly pregnancy questionnaire were assumed to be the same for all of the 4 weeks during the questionnaire period.

Pregnancy Outcome

Pregnancies were confirmed by study ultrasonography at 6 to 7 weeks with demonstrated pregnancy signs (eg, a visible gestational sac, clinical documentation of fetal cardiac activity, or later-stage confirmation of pregnancy). We categorized pregnancy loss as peri-implantation or clinically recognized loss.11 Peri-implantation loss was defined as (1) an hCG-positive urine pregnancy test result at home or the clinical site followed by the absence of signs of clinical pregnancy at the study ultra-sonography, with or without missed menses, or (2) an hCG-positive pregnancy test result via retrospective laboratory analysis with highly sensitive urine testing from daily first-morning urine collected at home on the last 10 days of women’s first and second cycle of study participation and on spot urine samples collected at all postcycle visits, followed by the absence of a positive pregnancy test result at home or in the clinic. The latter identified early implantation failures. Clinically recognized pregnancy losses were defined as a pregnancy loss after ultrasonographic confirmation. We included ectopic pregnancies; preembryonic, embryonic, and fetal losses; and stillbirths in our definition of clinically recognized pregnancy loss. No molar pregnancies occurred in this sample.

Statistical Analysis

Final follow-up was completed on August 25, 2012, and data were analyzed from January 21, 2015, to March 16, 2016. We compared bivariate descriptive statistics of maternal preconception characteristics by any nausea or vomiting symptoms using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test as appropriate. The association between weekly nausea and vomiting and the time to pregnancy loss was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models with time-varying covariates. We used 3 different models to examine peri-implantation and clinical pregnancy losses in aggregate, then individually. All models were adjusted for potential confounders and independent predictors of pregnancy loss.12 Time-fixed covariates included baseline variables, such as age, race, income, student status, attained educational level, employment status, marital status, number of prior pregnancy losses, number of prior live births, preconception body mass index calculated from measured weight and height, exercise level, multivitamin intake, low-dose aspirin treatment, gestational age of previous fetal loss, and fetal variables, including fetal sex, karyotype, and multiple-fetal gestation. Time-varying covariates collected on diaries and pregnancy questionnaires, simultaneously as nausea and vomiting, included stress, smoking, and caffeine and alcohol in-take.

We identified missing data as (1) owing to participant nonresponse and (2) missing diary data owing to study design because nausea and vomiting were not assessed during passive preconception follow-up. We used multiple imputation with 50 replicates to address missing data owing to nonresponse and included women’s baseline characteristics and relevant longitudinal data for the time-varying covariates.13 Some women became pregnant during passive preconception follow-up and, thus, did not provide nausea and vomiting data for gestational weeks 2 to 4 until the pregnancy diary was initiated; furthermore, some of these women could have had a pregnancy loss during this period. Our modeling strategy accounted for this left truncation, which indicates that the outcome of interest occurs before it can be observed in a study.14 Last, women who withdrew from the study and had an unknown pregnancy outcome were censored at the gestational age of their last study contact. All analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc).

Results

A total of 797 women (mean [SD] age, 28.7 [4.6] years) had an hCG-positive pregnancy test result. Women’s baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. All women had at least 1 prior pregnancy loss, with 34.3% having 2 prior losses. Most women (446 [56.0%]) were in active follow-up at conception (first 2 menstrual cycles since enrollment). Overall, 188 pregnancies (23.6%) ended in a loss. Of these, 55 (6.9% overall) were periimplantation losses and 133 (16.7% overall) were clinically recognized losses. The median gestational age at the time of loss was 7 weeks, with 25% occurring at 5 weeks or earlier and 25% occurring at 10 weeks or later. Ten losses occurred during passive follow-up and were therefore excluded because no exposure data were collected from these women. Twelve women with an unknown pregnancy outcome withdrew from the study and were censored at the time of last study contact (median, 14 weeks; interquartile range, 9–29 weeks).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) (N = 797)a |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| <25 | 180 (22.6) |

| 25–29 | 327 (41.0) |

| 30–34 | 202 (25.3) |

| ≥35 | 88 (11.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 769 (96.5) |

| Nonwhite | 28 (3.5) |

| Body mass indexb | |

| <18.5 | 31 (3.9) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 418 (52.4) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 187 (23.5) |

| ≥30.0 | 152 (19.1) |

| Missing | 9 (1.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 752 (94.4) |

| Other | 45 (5.7) |

| Annual household income, US$ | |

| <20 000 | 54 (6.8) |

| 20 000–39 999 | 187 (23.5) |

| 40 000–74 999 | 116 (14.6) |

| 75 000–99 999 | 114 (14.3) |

| ≥100 000 | 326 (40.9) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 576 (72.3) |

| Unemployed | 209 (26.2) |

| Missing | 12 (1.5) |

| Student status | |

| No | 684 (85.8) |

| Yes | |

| Full-time | 55 (6.9) |

| Part-time | 58 (7.3) |

| Educational level | |

| High school or less | 90 (11.3) |

| Beyond high school | 707 (88.7) |

| Exercise level | |

| Low | 210 (26.3) |

| Moderate | 327 (41.0) |

| High | 260 (32.6) |

| Vitamin supplements used | |

| None | 54 (6.8) |

| Other vitamins without folic acid | 120 (15.1) |

| Folic acid with or without other vitamins | 623 (78.2) |

| No. of prior pregnancy losses | |

| 1 | 524 (65.7) |

| 2 | 273 (34.3) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 336 (42.2) |

| 1 | 305 (38.3) |

| 2 | 156 (19.6) |

| Treatment | |

| Placebo | 385 (48.3) |

| Low-dose aspirin | 412 (51.7) |

| Fetal sexc | |

| Male | 301 (37.8) |

| Female | 319 (40.0) |

| Missing | 177 (22.2) |

| Multiple-fetal gestationc | |

| No | 612 (76.8) |

| Yes | 8 (1.0) |

| Missing | 177 (22.2) |

| Karyotypec | |

| Missing | 146 (18.3) |

| Normal | 620 (77.8) |

| Abnormal | 31 (3.9) |

Not all categories sum to 100% because of rounding.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. One hundred twenty-five calculations (15.9%) used a self-reported instead of a measured weight.

A high proportion of data were missing owing to an inability to characterize fetal sex, multiple-fetal gestation, or karyotype or among peri-implantation pregnancy losses.

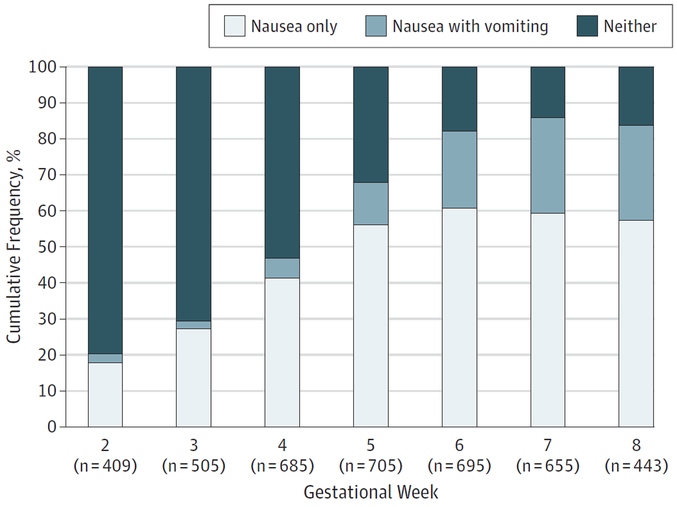

The incidence of nausea and vomiting assessed with daily diaries is shown in Figure 1. Daily diary adherence was high, with most women completing all 7 days in a given week. At least 87% of women completed the diary during gestational weeks 2 to 7. At gestational week 2, 73 of 409 women (17.8%) and 11 of 409 women (2.7%) who submitted diaries reported nausea without and with vomiting, respectively; by week 8, the proportions increased to 254 of 443 women (57.3%) and 118 of 443 women (26.6%), respectively.

Figure 1. Nausea and Vomiting During Gestational Weeks 2 to 8.

Participants rated nausea and vomiting via daily preconception and pregnancy diaries as none, nausea only, vomiting once per day, or vomiting more than once per day. The week-specific sample size depends on active or passive follow-up and on the number of women remaining pregnant at a given week.

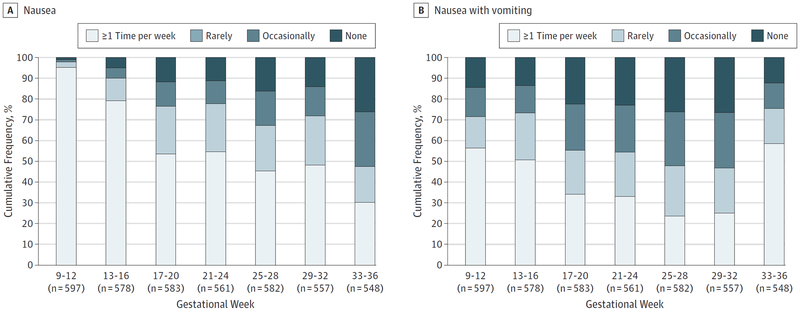

Nausea and vomiting frequency assessed via monthly pregnancy questionnaires is shown in Figure 2. Because nausea and vomiting in the past 4 weeks were asked in separate questions, Figure 2 shows the mean frequency of each symptom separately. Pregnancy questionnaire adherence was high, with at least 93% of women completing questionnaires in a given month. At week 12, 516 of 597 women (86.0%) reported having nausea and 207 of 597 (35.0%) reported having nausea with vomiting at least once per week in the preceding 4 weeks. Seven women (0.9%) were hospitalized at least once for vomiting or hyperemesis.

Figure 2. Nausea and Vomiting During Gestational Weeks 9 to 36.

From gestational weeks 12 to 36, participants completed monthly questionnaires describing their nausea and vomiting symptoms during the prior 4 weeks as never, rarely (once per month), occasionally (2 or 3 times per month), sometimes (1 or 2 times per week), often (3–6 times per week), or daily. Only participants who remained pregnant at the time of the questionnaire were asked to complete the questionnaire for the preceding 4 weeks, ensuring that all data were prospectively collected before the pregnancy outcome.Week-specific sample size depends on the number of women remaining pregnant at a given week.

In general, women who were younger than 25 years were more likely to have nausea or vomiting than older women (eTable in the Supplement). Few other preconception characteristics had clear patterns of association with nausea and vomiting in the earliest weeks.

Among women with 1 or 2 prior pregnancy losses and compared with women with neither symptom, women with nausea only or nausea with vomiting during a given week had a reduced hazard ratio of 0.50 (95% CI, 0.32–0.80) or 0.25 (95% CI, 0.12–0.51) for pregnancy loss during that week, respectively (Table 2). When limited to peri-implantation pregnancy losses only, the association was similar but not statistically significant (hazard ratios, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.29–1.20] and 0.51 [95% CI, 0.11–2.25], respectively). Among women who did not have a peri-implantation pregnancy loss, nausea only and nausea with vomiting remained associated with a reduced hazard ratio for clinical pregnancy loss of 0.44 (95% CI, 0.26–0.74) and 0.20 (95% CI, 0.09–0.44), respectively, each week for clinical pregnancy loss compared with women with neither symptom. The unadjusted and adjusted estimates were similar for all models.

Table 2.

Association of Nausea and Vomiting Symptoms During Pregnancy With Pregnancy Loss

| Pregnancy Loss | HR(95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Any(n = 178)a | ||

| Neither | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference]b |

| Nausea only | 0.44 (0.27–0.72) | 0.50 (0.32–0.80) |

| Nausea with vomiting | 0.19 (0.08–0.41) | 0.25 (0.12–0.51) |

| Peri-implantation (n = 46)a | ||

| Neither | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference]c |

| Nausea only | 0.65 (0.30–1.42) | 0.59 (0.29–1.20) |

| Nausea with vomiting | 0.67 (0.14–3.23) | 0.51 (0.11–2.25) |

| Clinical (n = 132)a,d | ||

| Neither | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference]b |

| Nausea only | 0.39 (0.22–0.68) | 0.44 (0.26–0.74) |

| Nausea with vomiting | 0.15 (0.06–0.35) | 0.20 (0.09–0.44) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Model accounts for left truncation (ie, passive follow-up schedule).

Time-varying covariates include smoking, stress, and caffeine and alcohol intake. Time-fixed covariates include age, race, income, student status, attained educational level, employment status, marital status, number of prior pregnancy losses, number of prior live births, preconception body mass index, exercise level, vitamin intake, low-dose aspirin treatment, gestational age of previous loss, fetal sex, karyotype, and multiple-fetal gestation.

Time-varying covariates include smoking, stress, and caffeine and alcohol intake. Time-fixed covariates include age, race, income, student status, attained educational level, employment status, marital status, number of prior losses, number of prior live births, preconception body mass index, exercise level, vitamin intake, low-dose aspirin treatment, and gestational age of previous loss. This model does not adjust for fetal sex, karyotype, or multiple-fetal gestation because these cannot be ascertained for the early losses.

Model was conditional on not having a peri-implantation loss.

Last, most pregnancy losses occurred during the first trimester (176 of 188 women [93.6%]). As an additional analysis, we limited the outcome to first trimester losses only. Results were similar with overall adjusted hazard ratios of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.28–0.72) and 0.19 (95% CI, 0.09–0.41) for the risk for loss associated with nausea only and nausea with vomiting, respectively.

Discussion

In this prospective preconception cohort of women with a history of 1 or 2 prior pregnancy losses and an hCG-confirmed pregnancy, nausea and nausea with vomiting during pregnancy were associated with a substantial reduction in the risk for pregnancy loss. Through novel ascertainment of daily symptoms early in pregnancy from conception, our findings suggest that nausea and vomiting are associated with a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk for peri-implantation pregnancy loss. Furthermore, given clinical recognition of pregnancy by ultrasonography at 6 to 7 weeks, the presence of nausea and vomiting were associated with a reduction in risk by more than half for clinical pregnancy loss. These findings persist even after accounting for rarely measured lifestyle and fetal factors. Our study confirms prior research that nausea and vomiting appear to be more than a sign of still being pregnant and instead may be associated with a lower risk for pregnancy loss.

Nausea and nausea with vomiting were common symptoms, even during the earliest weeks of pregnancy. For example, approximately 1 in 5 women reported symptoms even before they had positive pregnancy test results. Notably, very few preconception factors were associated with nausea and vomiting, suggesting few modifiable risk factors. Prior retrospective studies that focused on the natural history of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy1,15 reported lower levels of nausea during the earliest weeks of pregnancy but relied on symptoms recalled late in the first trimester or even post partum. Alternatively, a recent prospective study that also assessed symptoms from weeks 2 to 7 using daily diaries16 observed more frequent levels of symptoms. Given the retrospective nature of most prior data, comparing the frequency of nausea across populations is difficult.

Our finding that nausea and vomiting were associated with a reduction in the risk for pregnancy loss is consistent with published literature. In our study, nausea alone or nausea with vomiting was associated with a 50% to 75% reduction in the risk for pregnancy loss. Prior studies have mostly been limited to examining losses late in or after the first trimester3–5; therefore, our clinical pregnancy loss findings are comparable to those of the prior literature. These studies all similarly observed a reduced pregnancy loss rate with nausea and vomiting, but the strength of the association varied because the timing of the retrospective collection was different across studies. A recent analysis with prospective collection of nausea and vomiting data observed that only vomiting was associated with a reduced risk for pregnancy loss.16 This null finding related to nausea may have been owing to power, with only 95 losses and nausea and vomiting symptoms that were collected for only the first 5 weeks of pregnancy. Our study is unique in that we prospectively assessed symptoms and provide data on the risk for peri-implantation and clinical pregnancy losses separately. Notably, almost one-third of all pregnancy losses were peri-implantation, meaning that the loss occurred before detection by the clinical ultrasonography at weeks 6 to 7.17 Our findings related to peri-implantation pregnancy loss provide preliminary suggestion of a reduced risk because they are similar in direction and magnitude to the clinical loss findings but do not reach statistical significance. The study was not powered to assess peri-implantation pregnancy loss because only a small number of cases were available, but our data provide important preliminary results that other studies have been unable to determine because most studies enroll women too late in gestation to assess this risk for early loss. Thus, these findings await corroboration.

Many theories have been proposed regarding the potential mechanism for an association between nausea and vomiting and pregnancy loss. First, symptoms may be part of an evolutionary advantage to change one’s dietary intake, increase consumption of carbohydrate-rich foods, or avert in-take of potentially teratogenic substances.18,19 Our modeling strategy accounted for smoking, alcohol and caffeine intake, and stress at each week, suggesting that the mechanism is likely not through avoidance of such substances. Second, the connection between nausea and pregnancy loss may be due to effects of hCG.19,20 Although β-hCG does not necessarily correlate with nausea and vomiting, β-hCG levels are known to be increased in multiple-fetal gestations and trisomy 21.21 A unique aspect of our study was the inclusion in analytic models of rarely studied fetal factors (ie, sex, multiple-fetal gestation, and karyotype) that may contribute to variation in nausea symptoms through their effect on hCG levels and thus affect pregnancy loss; notably, our findings related to clinical pregnancy loss persisted after accounting for these factors. Another possibility is that nausea and vomiting are markers for viable placental tissue. Thus, less nausea and vomiting may identify failing pregnancies, with lower hormone levels leading to nausea and vomiting.

Our study had many strengths. The systematic, prospective data collection from preconception onward provided an advantage. Using preconception daily diaries, we obtained rare data on the natural history of nausea and vomiting starting from gestational week 2 (ie, conception). This approach allowed for unique assessment of the association of nausea symptoms with peri-implantation pregnancy loss. An additional advantage was our accounting for the fact that women’s symptoms were not continuous every week and could wax and wane with intermittent weeks. Most previous studies have assessed nausea and/or vomiting as either a single variable for the entire period3,4,6 or treated it as a continuous exposure from the date reported that symptoms started to their end date.5 We also accounted for time-varying covariates, including behavioral factors and rarely available covariates, such as karyotype, that help to elucidate the potential biological mechanism. Last, all pregnancy losses, including peri-implantation losses, were thoroughly identified in this cohort, which may make the incidence of pregnancy loss appear high compared with studies that do not capture these early losses, but this estimate is consistent with prior estimates with thoroughly ascertained losses.22

The study had several limitations. First, this study was conducted within a rather homogeneous sample of women, which may limit generalizability. Daily early nausea and vomiting symptoms were not captured for women who became pregnant during the passive follow-up phase (ie, cycles 3–6) and did not complete the preconception daily diary during the relevant time window; however, exclusion of women who became pregnant during passive study follow-up did not appreciably change estimates or the reported findings. Furthermore, our modeling strategy accounted for this systematic exclusion (ie, left truncation). Although daily diary adherence was very high, missing data were thoroughly addressed using multiple imputation and leveraging women’s extensive longitudinal data (eg, prior and subsequent symptoms and related factors, such as stress and caffeine and alcohol intake) to optimally inform imputation. Also, a small proportion of women had hyperemesis; we were unable to assess the impact of this severe form of nausea. Notably, the rate of hyperemesis in our study was consistent with rates in other reports.23

Conclusions

Among women with 1 or 2 prior pregnancy losses, nausea and nausea with vomiting during pregnancy were associated with a 50% to 75% reduction in the risk for pregnancy loss. Nausea and vomiting symptoms were common very early in pregnancy. These findings overcome prior analytic and design limitations and represent the most definitive data available, to our knowledge, indicating the protective association of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy on the risk for pregnancy loss and thus may provide reassurance to women experiencing these difficult symptoms in pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Key Points

Question

Are nausea and vomiting in pregnancy associated with the risk for pregnancy loss?

Findings

In this prospective preconception cohort of 797 women with a pregnancy confirmed by human chorionic gonadotropin test results, nausea and nausea with vomiting during pregnancy were associated with a substantial reduction in the risk for pregnancy loss.

Meaning

These findings indicate a protective association of maternal nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy with the risk for pregnancy loss and may provide reassurance to women experiencing these difficult symptoms in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by contracts HHSN267200603423, HHSN267200603424, and HHSN267200603426 from the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lacroix R, Eason E, Melzack R. Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: a prospective study of its frequency, intensity, and patterns of change. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182(4):931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood H, McKellar LV, Lightbody M. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: blooming or bloomin’ awful? a review of the literature. Women Birth 2013;26(2): 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klebanoff MA, Koslowe PA, Kaslow R, Rhoads GG. Epidemiology of vomiting in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1985;66(5):612–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weigel MM, Weigel RM. Nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy and pregnancy outcome: an epidemiological study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1989; 96(11):1304–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan RL, Olshan AF, Savitz DA, et al. Severity and duration of nausea and vomiting symptoms in pregnancy and spontaneous abortion. Hum Reprod 2010;25(11):2907–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weigel MM, Reyes M, Caiza ME, et al. Is the nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy really feto-protective? J Perinat Med 2006;34(2):115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tierson FD, Olsen CL, Hook EB. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and association with pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;155 (5):1017–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1999;340(23):1796–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schisterman EF, Silver RM, Lesher LL, et al. Preconception low-dose aspirin and pregnancy outcomes: results from the EAGeR randomised trial. Lancet 2014;384(9937):29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schisterman EF, Silver RM, Perkins NJ, et al. A randomised trial to evaluate the effects of low-dose aspirin in gestation and reproduction: design and baseline characteristics. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27(6):598–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumford SL, Silver RM, Sjaarda LA, et al. Expanded findings from a randomized controlled trial of preconception low-dose aspirin and pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod 2016;31(3):657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauck WW, Anderson S, Marcus SM. Should we adjust for covariates in nonlinear regression analyses of randomized trials? Control Clin Trials 1998;19(3):249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou XH, Eckert GJ, Tierney WM. Multiple imputation in public health research. Stat Med 2001;20(9–10):1541–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cain KC, Harlow SD, Little RJ, et al. Bias due to left truncation and left censoring in longitudinal studies of developmental and disease processes. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173(9):1078–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louik C, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: maternal characteristics and risk factors. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2006;20(4):270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapra KJ, Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, et al. Signs and symptoms associated with early pregnancy loss: findings from a population-based preconception cohort. Hum Reprod 2016;31(4): 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silver RM, Branch DW, Goldenberg R, Iams JD, Klebanoff MA. Nomenclature for pregnancy outcomes: time for a change. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 118(6):1402–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coad J, Al-Rasasi B, Morgan J. Nutrient insult in early pregnancy. Proc Nutr Soc 2002;61(1):51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furneaux EC, Langley-Evans AJ, Langley-Evans SC. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: endocrine basis and contribution to pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2001;56(12):775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niebyl JR. Clinical practice: nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2010;363(16): 1544–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jauniaux E, Nicolaides KH, Nagy A-M, Brizot M, Meuris S. Total amount of circulating human chorionic gonadotrophin α and β subunits in first trimester trisomies 21 and 18. J Endocrinol 1996; 148(1):27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1988;319(4):189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiaschi L, Nelson-Piercy C, Tata LJ. Hospital admission for hyperemesis gravidarum:a nationwide study of occurrence, reoccurrence and risk factors among 8.2 million pregnancies. Hum Reprod 2016;31(8):1675–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.