Abstract

Introduction:

Hair loss is a common and distressing clinical complaint in the dermatology clinics. Common causes of hair loss in children include alopecia areata, tinea capitis, traction alopecia, and trichotillomania. Newly, trichoscopy allows differential diagnosis of hair loss in most cases and allows visualization of hair shafts and scalps without the need of removing hair.

Objective:

The main objective is to compare the different trichoscopic features of common causes of patchy hair in children loss including tinea capitis, alopecia areata, traction alopecia, and trichotillomania.

Patients and Methods:

This study included 134 patients, 63 patients with tinea capitis, 38 patients with alopecia areata, 18 patients with traction alopecia, and 15 patients with trichotillomania. The diagnostic tools for the diagnosis of hair loss problem included a detailed history, evaluation of the child's hair and scalp, fungal scrapping, and trichoscopy.

Results:

Tinea capitis was the most common, and the trichoscopic features were comma-shaped hairs, corkscrew hairs, short broken hairs, and interrupted hairs. While in alopecia areata patients, the most specific features were yellow dots and black dots, microexclamation mark, hair shafts with variable thickness, and vellus hairs, with uncommon features included: monilethrix, coiled, zigzag, and tulip hairs. Trichoscopy of trichotillomania showed hair with fraying of ends, breakage at different lengths, short and coiled hairs, and amorphous hair residues. The trichoscopic features of traction alopecia were similar to those of trichotillomania. However, flame hairs and coiled hairs were less common.

Conclusions:

Trichoscopy is a noninvasive method of examining hair and scalp. It allows differential diagnosis of hair loss in most cases.

Key words: Children, hair loss, trichoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Hair loss or alopecia is a common and distressing clinical complaint in dermatology and pediatric clinics. This is a particularly important problem at this age group, and early diagnosis is of particular importance. Hair loss in children often presents with clinical features and patterns that are different from those of the adult population. Common causes of hair loss in children[1,2] include alopecia areata, tinea capitis, traction alopecia, and trichotillomania. In addition to the previous, other less common causes of hair loss[2] can be seen including bacterial infections and systemic illnesses such as thyroid disorders, iron deficiency anemia, malnutrition, and structural abnormalities of the hair shaft.

Diagnosis of hair loss in children includes a detailed history, physical examination of the child's hair and scalp, fungal screen, laboratory investigation for complete blood count, serum iron, serum zinc, thyroid function test, and others, which are necessary in some cases. Newly, dermoscope (trichoscope)[3,4] is a noninvasive method of examining the hair and scalp. It allows differential diagnosis of hair loss in most cases. The method allows visualization of hair shafts and scalps at high magnification and performing assessment of the scalp and hair without the need of making a scalp biopsy or removing hair. Several reports[4,5,6] raise the issue of the usefulness of this new technique in congenital and acquired causes of hair loss.

All of the previous studies investigate this problem in children concentering on a specific disease such as tinea capitis,[7,8] alopecia areata,[9,10] and trichotillomania.[10] This study investigated 134 children presented at dermatology clinics during the last 3 years complaining of nonscarring patchy hair loss. The cases which were diagnosed with tinea capitis, alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and traction alopecia were investigated with trichoscopy. A previous study done[2] in Jordan documented the clinical and epidemiological setting of common and uncommon cases of hair loss in children. Hair types are influenced by ethnic groups and this varies from region to region, and subsequently, this may reflect itself on the variation of common and uncommon trichoscopic features. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the common and uncommon trichoscopic features for the common causes of hair loss in Jordan; comparing the findings with the previous reports and documenting the frequency of them.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A total of 134 children were seen at the Dermatology Clinics (Mutah University Medical Center) during January 2015–October 2017 complaining of patchy hair loss, without sex predilection and their age (≤14 years). They presented with solitary or multiple lesions of patchy hair loss of the scalp. The exclusion criteria were patients with a history of using any topical (1 month) or systemic treatment (3 months) for the hair loss before the study. The data were collected from the patient's parents and informed consent was obtained.

The diagnostic tools for the diagnosis of hair loss problem included a detailed history, physical examination with a focused evaluation of the child's hair and scalp, fungal scrapping, and trichoscopy. A detailed history was taken regarding the clinical presentation (patchy or diffuse hair loss, presence of scales or itching, and other hairy areas involvement). In addition, a detailed history was taken about animal contacts, hair grooming/habit tics, and other cutaneous changes.

Scalp examination included the presence of erythema and scales. Hair examination included the recording of hair color, texture, fragility, and examination of the hair root. In addition to the scalp, other hairy sites were examined for hair loss (including eyebrows and eyelashes). All suspected cases of tinea capitis were investigated by Wood's light examination and skin and scalp scrapings for KOH (potassium hydroxide).

The initial diagnosis was made for all of the cases, that is, tinea capitis, alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and traction alopecia. Trichoscopic examination was done for all cases looking for specific diagnostic finding for each case of hair loss.

The trichoscopy was a handheld trichoscope (Dermlite DL3, Gen, USA) application which captured images with iPhone, and then was evaluated as saved photos on computer screen. This trichoscope can block light reflection from the skin surface without immersion gels or alcohol. The dates and times of capturing photos were automatically stored.

RESULTS

A total of 134 child patients attending Dermatology Clinics at Mutah University Medical Center, had scalp and hair disorders. The age range was from 4 months to 14 years. The most common presenting symptoms were patchy hair loss, scaly and erythematous scalp, itching, and pruritus.

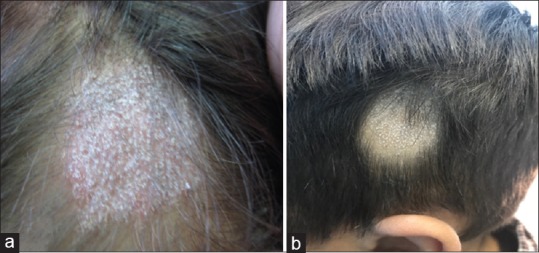

Tinea capitis was the most prevalent form of hair loss (63 patients, 47%) with mean age of 4 years. The presentation was common as patchy hair loss with scales and erythema. The mean duration of the cases was 2 weeks. The patches may be solitary or multiple. Other presentations of tinea capitis were seborrheic form, kerion abscess formation, and hair loss with black dots [Figure 1a and b]. The diagnosis of these cases of tinea capitis was confirmed by KOH scrapping for the scales. Trichoscopy was done for all cases [Table 1] and the reference for the evaluation was the trichoscopic findings described in the previous studies.[7,8,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

Figure 1.

(a) Tinea capitis in a child showed the presence of patch of hair loss with scaly and erythematous scalp. (b) Tinea capitis showed patch of hair loss with scales but no erythema and with the prominent black dots within the patch of hair loss

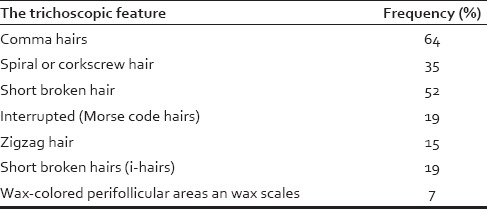

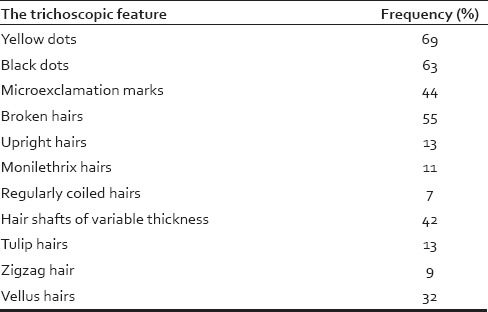

Table 1.

Different trichoscopic features in tinea capitis

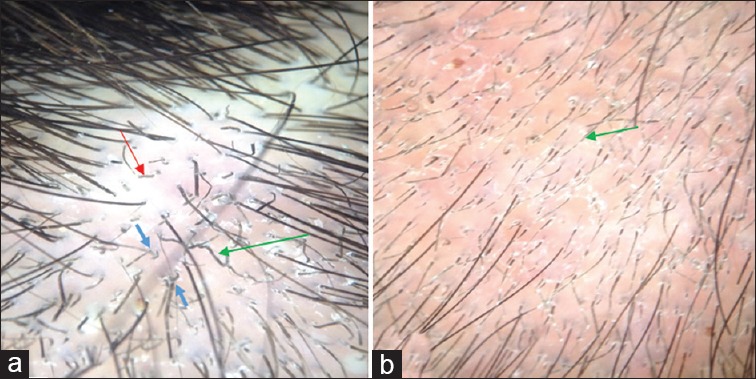

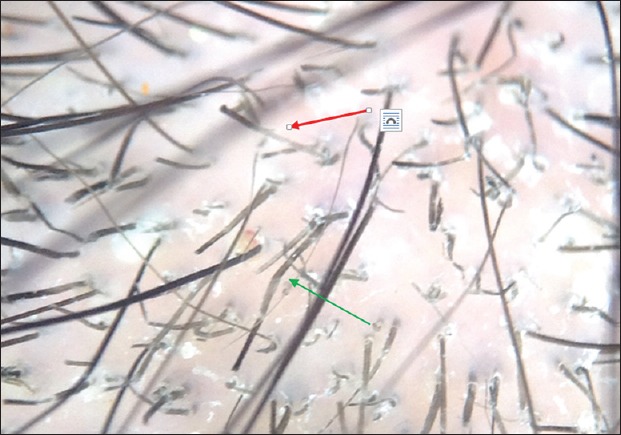

The common trichoscopic features findings in these cases were: comma hairs which were curved resembling commas, homogeneous in thickness, and evenly pigmented [Figure 2a]. These Comma hairs were the most common findings (64% of the cases). Spiral or corkscrew hair [Figure 2a] which was characterized by the presence of multiple twists and was intensely coiled like a spiral (35% of cases). Short broken hair [Figure 2a and b], this was a common feature and was seen in association with the previous two features (52%). This type of hair may have an accentuated distal end, making these hairs look even more like the letter i (i-Hairs) [Figure 3]. Interrupted hairs (Morse code hairs) [Figure 2b], and zigzag hair [Figure 3] which were sharply bent at multiple points and may fracture easily at these bending sites. The last trichoscopic feature of tinea capitis was large amorphous yellow areas and large wax-colored perifollicular areas, and this was seen in 7% of the cases [Figure 4].

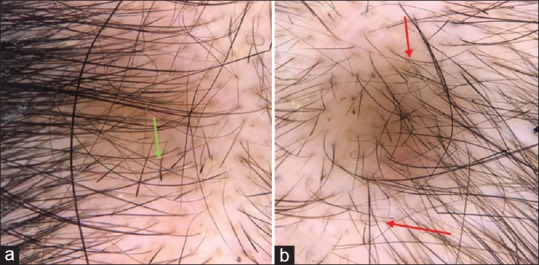

Figure 2.

(a) Trichoscopy of the scalp of a child with tinea capitis showed the presence of comma hair (blue arrows), short broken hair (red arrow), and spiral hair (green arrow). (b) This trichoscopic image showed with Morse code hairs or interrupted hairs (green arrow)

Figure 3.

This trichoscopic pictures showed zigzag hairs (green arrow) and short broke hairs (i-Hairs) (red arrows)

Figure 4.

Trichoscopy of favus showed erythema and wax-colored scales and with little or minimal involvement of hair shafts

Alopecia areata was the second form of hair loss, affecting 38 patients with mean age of 6.2 years. The earliest age of reporting alopecia areata in this study was 9 months (presented with multiple patches). The duration of the disease varied from 2 to 6 weeks at presentation. The presentation of patients was common with single or multiple patches of hair loss with no scales or erythema and with normal scalp appearance [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

A patch of alopecia areata showed patch of hair loss with no scales or erythema but with prominent microexclamation marks

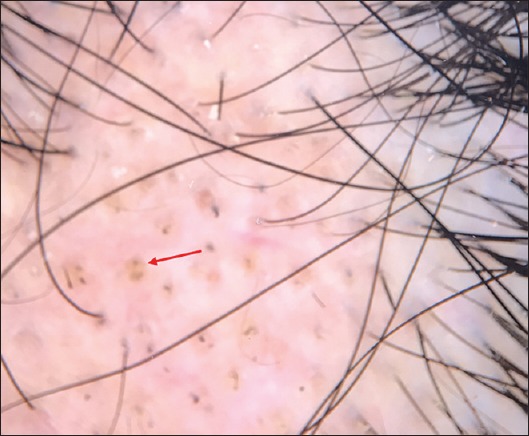

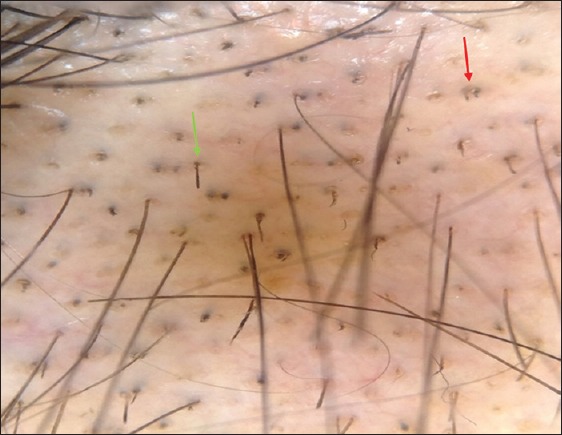

The common trichoscopic features of alopecia areata Were summarized in [Table 2] and the reference for the evaluation was the previous trichoscopic findings in alopecia areata in the previous studies.[21,22,23,24,25,26] These features included: regularly distributed yellow dots (69%) with hyperkeratotic plugs that fill the follicular infundibula [Figure 6], black dots (63%) which were pigmented residues of hairs destroyed, and broken at scalp level [Figure 7]. But if these broken above the skin surface, it will be demonstrated as short broken hair (55%).

Table 2.

Different trichoscopic features in alopecia areata

Figure 6.

Trichoscopic features of alopecia areata in a child showed regularly distributed yellow dots (red arrow)

Figure 7.

Trichoscopic pictures of alopecia areata demonstrating black dots (blue arrows), and multiple broken hairs (green arrows)

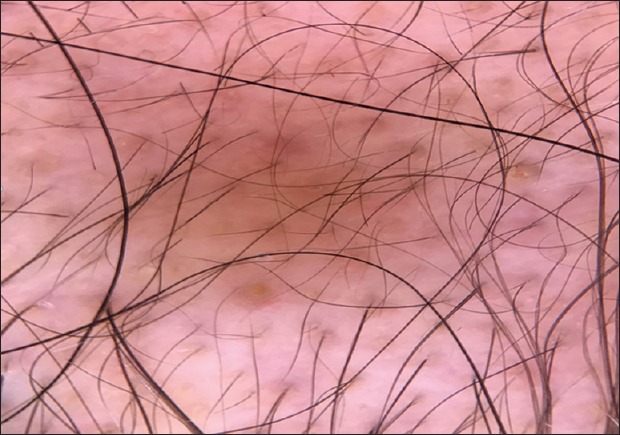

Microexclamation mark was another common trichoscopic features of alopecia areata (44%), which were thin at the proximal end and thicker at the distal end. Hair shafts of variable thickness in alopecia areata were common in this study (42%) [Figure 8]. Vellous hair was also prominent in these patients with a frequency of 32% of the cases.

Figure 8.

Trichoscopic features of alopecia areata demonstrates hair shafts with variable thickness, vellus hair, and with yellow dots

There were some uncommon trichoscopic features [Figure 9a and b] in alopecia areata including monilethrix- like hairs in alopecia areata (11%) which were constricted hair shafts at irregular intervals, regularly coiled hairs (circle, pigtail) (7%) into an oval or circular shape, tulip-like hairs (15%) which were hairs with dark distal end, and zigzag hairs (9%).

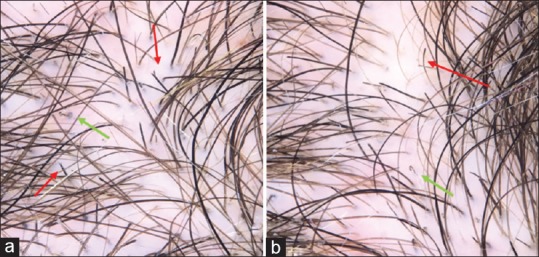

Figure 9.

(a) Trichoscopic figure for a child with alopecia areata showed the presence of multiple tulip hairs (green arrow). (b) Pigtail hair was prominent in this figure (red arrows)

Trichotillomania was another and significant form of patchy hair loss in this study. A total of 15 (11%) cases presented of hair loss with broken hairs of varying lengths arranged in a circular pattern, with unaffected hairs surrounding the area of hair loss. In addition to the scalp, four cases had eyebrows involvement. The skin of the scalp was normal with no scales or erythema. Patients present with patches of irregular-length hair or hairless areas [Figure 10]. Commonly, the vertex was affected. The mean age of presentation was 9 years with female predominance (13 cases are females).

Figure 10.

Trichotillomania in a child showed patch of hair loss, there was no scales or erythema, the hair was broken or cut at different levels

Trichoscopy of these cases [Figure 11a and b] showed fraying of ends (trichoptilosis) with characteristic irregular ends, breakage at different lengths and with extreme variability in morphology, short hairs, irregular coiled hairs, flame hairs with amorphous hair residues that was wavy and cone shaped, and black dots. Some of the cases showed scratching and hemorrhage. These features were common in all cases which were examined and nearly present in each case and was similar to previous trichoscopic features for trichotillomania in previous studies.[24,25,27,28]

Figure 11.

(a) Trichoscopic picture for a child with trichotillomania showed hair broken at different levels, trichoptilosis (red arrows), and flame hairs (green arrows). (b) Coiled hairs (green arrow) and tulip hairs (red arrow)

Traction alopecia was seen in 18 cases, occurring mainly around hairline. In some cases, hair cast had been identified. In addition, some cases showed follicular pustules and inflammation along the margin of alopecia [Figure 12].

Figure 12.

Traction alopecia

This study showed that the trichoscopic features of traction alopecia were similar to those of trichotillomania. These features include decreased hair density, broken hairs, and tulip hairs. However, flame hairs and coiled hairs are less common [Figure 13]. The other difference was all cases of traction alopecia showed hair casts (fine keratin cylinders) and perifollicular erythema.

Figure 13.

Trichoscopy of a child with traction alopecia showed reduction in the hair density, perifollicular erythema, and cast formation (red arrows)

DISCUSSION

Hair loss is generally a common and distressing problem in dermatology clinics. It is of particular concern in pediatric population as it is associated with psychological complications that may arise and affect this important growing stage of the life.

Common causes of hair loss in children include alopecia areata, tinea capitis, traction alopecia, and trichotillomania. Diagnostic tool for these cases is well established in literature. Newly, trichoscopy is used for diagnosis of hair loss problems. It is a noninvasive technique and this is of particular concern, especially in children; it helps to confirm the diagnosis and make proper follow-up of hair loss and scalp disorders without disturbing the child. With the presence of trichoscopy, it is easy to make follow-up of patients and to assess the activity or chronicity of the diseases and subsequently the response to treatment. In the last few years, few published studies support using trichoscopy of hair loss in children. In the present study, 63 cases of tinea capitis patients were investigated.

Tinea capitis[11,12,13,14] is a superficial fungal infection of the scalp and hair. Children are most commonly affected by the disease. The disease is primarily caused by dermatophytes (trichophyton and microsporum). In tinea capitis, the in vivo hair invasion are distinguished morphologically to ectothrix (fungal hyphae cover the outside of hair follicle), endothrix (fungal hyphae filling the hair shaft), and favus (hair invasion is associated with formation of characteristic air spaces within the infected hair shaft). Clinically, tinea capitis distinguished in to inflammatory and noninflammatory. The noninflammatory tinea capitis is frequently caused by anthropophagic fungi. It is predominantly characterized by the presence of foci of short hairs broken at different lengths and black dots with minimal scaling and subtle erythema. This noninflammatory type may have the same clinical appearance of alopecia areata, so trichoscopy may be a useful diagnostic tool for diagnosis. The inflammatory tinea capitis is typically Presented as a patch of hair loss with inflammation, scaling, pustules, and itching.

In this study, 38 cases were inflammatory, 22 cases were noninflammatory, and three cases with favus. High incidence of inflammatory tinea capitis which is caused by zoophilic or geophilic fungi is expected in Jordan (most of the cases had history of contact with animals or infected soil).

In the present study, the trichoscopic features of tinea capitis were comma hairs (64%), spiral or corkscrew hair (35%), short broken hair (52%), interrupted (Morse code hair) (19%), zigzag hair (15%), short broken hair (i-hairs) (19%), and wax-colored scales (7%).

In the present study, comma-shaped[15,16,17,18] hairs were seen in 64%, which are slightly curved and fractured hair shafts. Bending of infected hair shafts (comma shaped-hairs) is probably a result of partial damage to hair shafts filled with hyphae or damage to the hair cuticle.[17,18] It has been documented that comma hairs may be associated with both the ectothrix and endothrix types of fungal invasion,[16,17] it has been detected in tinea capitis due to Microsporum canis, Microsporum langeronii, Trichophyton tonsurans, Trichophyton violaceum, and Trichophyton soudanens. Moreover, this was confirmed here in this research as it was demonstrated in both inflammatory and noninflammatory tinea capitis.

The spiral or corkscrew hair was seen in 35% of the cases, and seems to be a variation of comma hair that by the presence of multiple twists and an intensely coiled shape. Zigzag-shaped hairs were seen in 15%, these are sharply bent hairs at multiple points and may fracture easily at the bending sites. The mechanism leading to formation of zigzag hairs in tinea capitis remains unclear.[18]

The interrupted hairs (Morse code)[7,18] were seen in 19% of cases and were characterized by the presence of multiple transverse relatively regularly distributed throughout the hair shaft. These hairs may bend at these gaps to form zigzag shapes and then may fracture to form the short broken hair.

Short broken hairs were seen commonly in this study (52%), and this was expected as this type of hair result from breakage of spiral, zigzag, and interrupted hairs at their weakest points. This short broken hairs may be nonspecific trichoscopic finding of tinea capitis but may be a sign of severity of the disease.[9] This short broken hair in this study demonstrated specific pattern in some cases as i-shape (i-Hairs[18]), which were short broken hairs with an accentuated distal end. There may be a thin hypopigmented band (gap) directly beneath the dark distal end, making these hairs look even more like the letter i.[18] This study was conducted on a huge sample of patients and demonstrated these findings in 19% of cases. Only three cases of favus was seen in this research, the most prominent trichoscopic features was the presence of perifollicular yellowish wax.

The second common type of hair loss in this study was alopecia areata; 38 patient were investigated by trichoscopy looking for features of the disease. Typically, the patients presented with symptoms of hair loss with normal scalp, the patches may be single or multiple (most common).

The reported trichoscopic features in previous studies are regularly distributed yellow dots, microexclamation mark hairs, tapered hairs, black dots (formerly called cadaverous hairs), broken hairs, short vellus hairs, and regrowing upright or regrowing coiled hairs.[16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] Trichoscopy of alopecia areata may differ depending on disease activity, severity, and duration.[22] All of these trichoscopic features have been observed in the current study as summarized in Table 2.

In the present study, yellow dots are detected in 69% of alopecia areata patients; this finding was detected in other studies;[9,10,21] these are marked by distinctive array of yellow to yellow-pink, hyperkeratotic plug that varies in size and fills the follicular infundibula. They are arranged in groups, reflecting the number of hair shafts per follicular unit. The second common finding in alopecia areata was the black dots (63%). This finding was detected in other studies and represented remnants of broken hairs when hair shaft fractured before emerging from the scalp. The presence of black dots with broken hairs (55% of patients in this study) correlates positively with disease activity[22] and can be considered as a bad prognostic sign and very consistent marker of disease activity. Whereas, yellow dots tend to be present more commonly in patients with inactive alopecia areata than in those with active disease.[23]

Microexclamation marks were a common finding in this study (44%). The microexclamation marks are hairs that are thin at the proximal end and thicker at the distal end, but observed on trichoscopy and are <1 cm (~0.5 in) long.[23] This mark in alopecia areata may result from a transient phase of cell degeneration among precortical keratinocytes and defective cortex differentiation.[24] In this study, it was sign of active alopecia areata, as it was seen in the active cases of alopecia areata at the periphery of the lesion(s), and was more sensitive and diagnostic when associated with yellow dots, and black dots or short vellus hairs. This research demonstrated that it had been common to find black dots, broken hairs in nearly half. This had been distributed through the patches of alopecia areata and associated with peripheral microexclamation marks. These signs of activity of alopecia areata in this study could be explained by short duration time of presentation of the cases (2–6 weeks) and with the exclusion of cases who started on treatment before the study.

In the present study under trichoscopic examination, short vellus hair was detected in 32% of alopecia areata cases. Short vellus hairs were seen as new regrowing hair, which may not be detected clinically. It has been mentioned that the appearance of clusters of short vellus hairs is a possible sign of spontaneous remission or adequate treatment and the nondestructive nature of the disease.[25] In the present study, it had been in some cases even before starting the treatment; this may explain the spontaneous cure of alopecia areata even without treatment. Moreover, this also supports the frequency of presence of hair shafts with variable thickness (42%); these hairs were thin at the proximal end, becoming thicker in the mid part and then thinner toward the distal end.

Pigtail regrowing hair or regularly coiled hair[24,25] demonstrate the regrowth of terminal hair from hair follicles that are not fully intact. Although this was uncommon finding in this research, but it may represent a possible sign of spontaneous remission of alopecia areata. Other trichoscopic features of alopecia areata in this study were tulip hair, which was different from exclamation marks in that they are only slightly thinned at the proximal end and have light-colored hair shafts with only a dark distal end, and this dark distal end corresponds to an area of increased pigmentation exhibiting a tulip leaf-like shape.[24,25] Some of the uncommon trichoscopic features in this study were zigzag hairs (9%) (hairs bend at sites of trichorrhexis nodosa), and monilethrix hairs (11%), especially in active, and early alopecia areata.

Trichotillomania was the another important cause of patchy hair loss that was investigated in this study, 15 cases had been examined by trichoscopy. This disease represents the most common and most difficult differential diagnosis for alopecia areata, especially in children. All of the cases presented to the clinic complaining of hair loss and the initial parent's thought was alopecia areata. Because of this, it is necessary to use a tool to document the presence of diagnostic features for the disease to confirm the diagnosis. Trichotillomania is not a simple diagnosis; specific psychological assessment is needed for the child.

The known trichoscopic features for this disease are decreased hair density, hairs broken at different lengths, irregularly coiled hairs, and sparse yellow dots that may or may not contain black dots.[27] Trichoscopy of these cases showed fraying of ends, breakage at different lengths, short hairs, trichoptilosis (“split ends”), irregular coiled hairs, amorphous hair residues, and black dots. Some of the cases showed scratching and hemorrhage. These features were common in all cases which are examined and nearly present in each case examined. Yellow dots were absent in all cases, and this was similar to the previous studies.[28] Microexclamation mark was a rare feature and was absent in all cases of this study. This may be an important diagnostic marker to differentiate it from cases of alopecia areata.

Traction alopecia, which is most commonly caused by hairstyling procedures, was seen in 18 cases of this study. Most of the cases complain of alopecia at the temporal and frontal margins. This was not uncommon in Jordan; as the trend to keep hair long for female's child and to tie it firmly as ponytails. Traction alopecia shows similar trichoscopic features to trichotillomania.[29,30] In addition, hair casts and perifollicular erythema may be seen. This type of alopecia is significant in children as it may be associated with perifollicular fibrosis and scarring alopecia if left untreated.

CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, tinea capitis was the most common to cause patchy hair loss in children. The most trichoscopic feature was comma hair followed with short broken hair and then spiral hair. There were no microexclamation marks or yellow dots. Yellow dots, exclamation mark hair, and short vellus hair are specific to alopecia areata. In alopecia areata, the most common trichoscopic feature was yellow dots, followed by black dots, micro-exclamation mark, hair shafts with variable thickness, and short vellus hairs. Some of the trichoscopic features can be used to predict the activity and severity of alopecia areata such as the presence of black dots or microexclamation marks. The tapering hair or microexclamation hair was considered as a marker of disease activity and known to reflect exacerbation of disease. These findings can be helpful in follow-up the activity of the disease and the response to treatment. Trichotillomania is an important differential diagnosis for alopecia areata, but the absence of yellow dots in trichotillomania can be a differential point. This study also showed that black dots was not a specific sign for all cases, as it has been detected in cases of trichotillomania and tinea capitis and alopecia areata, while yellow dots had been seen only in alopecia areata.

As a conclusion, trichoscopy is useful for the diagnosis and follow-up of hair and scalp disorders. This will enable dermatologists to make fast diagnoses of tinea capitis, alopecia areata, trichotillomania and traction alopecia. It helps not only for the diagnosis but also it eases the follow-up and assessment of the progression and the activity of all of the mentioned causes of hair loss in children. In my county, this was the first work to be published regarding this issue, and it will be a guide for all dermatologist to follow.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mandt N, Vogt A, Blume-Peytavi U. Differential diagnosis of hair loss in children. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2004;2:399–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0353.2004.04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Refu K. Hair loss in children: Common and uncommon causes; clinical and epidemiological study in Jordan. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:185–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.130393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudnicka L, Rakowska A, Kerzeja M, Olszewska M. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: Clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:695–708, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lencastre A, Tosti A. Role of trichoscopy in children's scalp and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:674–82. doi: 10.1111/pde.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tosti A, Whiting D, Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Misciali C, Vincenzi C, et al. The role of scalp dermoscopy in the diagnosis of alopecia areata incognita. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:64–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Rudnicka L. Trichoscopy in genetic hair shaft abnormalities. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2008;2:14–20. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2008.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elghblawi E. Tinea capitis in children and trichoscopic criteria. Int J Trichology. 2017;9:47–9. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_54_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourezane Y, Bourezane Y. Analysis of trichoscopic signs observed in 24 patients presenting tinea capitis: Hypotheses based on physiopathology and proposed new classification. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2017;144:490–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Taweel AE, El-Esawy F, Abdel-Salam O. Different trichoscopic features of tinea capitis and alopecia areata in pediatric patients. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:848763. doi: 10.1155/2014/848763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khunkhet S, Vachiramon V, Suchonwanit P. Trichoscopic clues for diagnosis of alopecia areata and trichotillomania in Asians. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:161–5. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niczyporuk W, Krajewska-Kułak E, Łukaszuk C. Tinea capitis favosa in Poland. Mycoses. 2004;47:257–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: A current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta AK, Summerbell RC. Tinea capitis. Med Mycol. 2000;38:255–87. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.4.255.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jankowska-Konsur A, Dylag M, Szepietowski JC. Tinea capitis in Southwest Poland. Mycoses. 2009;52:193–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes R, Chiaverini C, Bahadoran P, Lacour JP. Corkscrew hair: A new dermoscopic sign for diagnosis of tinea capitis in black children. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:355–6. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekiz O, Sen BB, Rifaioğlu EN, Balta I. Trichoscopy in paediatric patients with tinea capitis: A useful method to differentiate from alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1255–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slowinska M, Rudnicka L, Schwartz RA, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Rakowska A, Sicinska J, et al. Comma hairs: A dermatoscopic marker for tinea capitis: A rapid diagnostic method. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:S77–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudnicka L. Atlas of Trichoscopy: Dermoscopy in Hair and Scalp Disease. London, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, Micali G. Newly described features resulting from high-magnification dermoscopy of tinea capitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:308–10. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karadağ Köse Ö, Güleç AT. Clinical evaluation of alopecias using a handheld dermatoscope. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:206–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mane M, Nath AK, Thappa DM. Utility of dermoscopy in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:407–11. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacarrubba F, Dall'Oglio F, Rita Nasca M, Micali G. Videodermatoscopy enhances diagnostic capability in some forms of hair loss. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:205–8. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inui S, Nakajima T, Nakagawa K, Itami S. Clinical significance of dermoscopy in alopecia areata: Analysis of 300 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:688–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, Slowinska M. Trichoscopy update 2011. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:82–8. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2011.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Slowinska M. Trichoscopy: A new method for diagnosing hair loss. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:651–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobin DJ. Morphological analysis of hair follicles in alopecia areata. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38:443–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970815)38:4<443::AID-JEMT12>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham LS, Torres FN, Azulay-Abulafia L. Dermoscopic clues to distinguish trichotillomania from patchy alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:723–6. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DY, Lee JH, Yang JM, Lee ES. The use of dermoscopy for the diagnosis of trichotillomania. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:731–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hantash BM, Schwartz RA. Traction alopecia in children. Cutis. 2003;71:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tosti A, Miteva M, Torres F, Vincenzi C, Romanelli P. Hair casts are a dermoscopic clue for the diagnosis of traction alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1353–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]