Abstract

BACKGROUND

Over 1.8 million new cases of HIV-1 infection were diagnosed worldwide in 2016. No licensed prophylactic HIV-1 vaccine exists.

METHODS

This randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase I/IIa clinical trial evaluated the safety and immunogenicity of adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector-based HIV-1 vaccine regimens in 393 participants in Eastern Africa, South Africa, Thailand and the United States. Participants were randomly assigned to treatment groups based on a computer-generated randomization code. Vaccine regimens included priming with Ad26 vectors expressing mosaic Env/Gag/Pol antigens and boosting with Ad26 or MVA vectors expressing these antigens with or without aluminum adjuvanted clade C Env gp140 protein. A parallel study in 72 rhesus monkeys assessed the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of these vaccine regimens against repetitive, heterologous, intrarectal challenges with simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-SF162P3).

RESULTS

All vaccine regimens demonstrated favorable safety and tolerability. The mosaic Ad26 prime/Ad26+gp140 boost vaccine was the most immunogenic in humans; it elicited Env-specific binding antibody responses, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis responses, and T-cell responses in 100%, 80% and 83% of vaccine recipients, respectively. This vaccine regimen induced similar magnitude, durability, and phenotype of immune responses in rhesus monkeys and afforded 66% protection against acquisition of infection following a series of six SHIV-SF162P3 challenges. Env-specific ELISA and ELISPOT responses were the principal immune correlates of protection against SHIV challenge in monkeys.

CONCLUSIONS

The mosaic Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HIV-1 vaccine induced comparable and robust immune responses in humans and rhesus monkeys, and it provided significant protection against heterologous SHIV challenges in monkeys. This vaccine regimen is currently being evaluated in a phase IIb clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the success of antiretroviral therapy for both treatment and prevention of HIV-1 infection,1–4 a safe and effective vaccine will likely be needed to achieve a practical and durable end to the global HIV-1 pandemic.5,6 However, the challenges associated with the development of an HIV-1 vaccine are unprecedented. Key scientific hurdles include the extensive genetic diversity of the virus, the rapid establishment of latent viral reservoirs, and the lack of definitive immune correlates of protection.7,8

To date, four HIV-1 vaccine concepts have been evaluated for efficacy in humans. Clinical efficacy studies with HIV-1 envelope (Env) gp120 subunit vaccines,9,10 adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) vectors expressing the internal proteins Gag/Pol/Nef,11,12 and a DNA vaccine prime with an Ad5 vector boost13 did not prevent acquisition of HIV-1 infection in the populations studied and resulted in increased infection risk in certain subgroups. In contrast, a canarypox ALVAC vector prime with an Env gp120 boost provided 31% vaccine efficacy in a study in Thailand,14 and a clade C version of this vaccine is currently being evaluated in South Africa (NCT02968849).15,16

One key hurdle for HIV-1 vaccine development is to elicit greater immune breadth to circulating strains of HIV-1.9–13To address the challenge of global HIV-1 diversity, we developed bioinformatically optimized bivalent global “mosaic” antigens that aim to expand immunologic coverage of HIV-1 M group viruses.17,18 To express mosaic Env and Gag-Pol immunogens, we used adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vectors,19 which differ substantially from Ad5 vectors in cellular receptor usage, tropism, innate inflammatory responses, adaptive immune phenotypes, and baseline neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers in human populations.20 Phase I clinical trials with prototype Ad26 vectors expressing a single HIV-1 Env insert have demonstrated induction of robust Env-specific immune responses in both peripheral blood and colorectal mucosa.21–24

Preclinical evaluations of HIV-1 vaccine candidates typically utilize simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) or simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) challenge models in rhesus monkeys. Ad26 vectors expressing Env and Gag-Pol immunogens boosted with modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vectors expressing these immunogens demonstrated partial protection against SIVmac251 and SHIV-SF162P3 challenges in rhesus monkeys.25,26 Moreover, Ad26 vectors expressing these immunogens boosted with a purified SIV Env gp140 protein afforded improved protection against heterologous SIVmac251 challenges.27 These vaccines did not induce broad nAb responses, and correlates of protection were Env specific binding and functional antiviral antibody responses, including antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP).27,28

A major limitation in the HIV-1 vaccine field to date has been the lack of direct comparability between preclinical studies and clinical trials, in terms of the vaccines, regimens, schedules, and assays utilized. We therefore evaluated the leading mosaic Ad26-based HIV-1 vaccine candidates in similarly designed preclinical and clinical studies to define the optimal HIV-1 vaccine regimen to advance into clinical efficacy trials.

METHODS

APPROACH CLINICAL STUDY

STUDY DESIGN

APPROACH (NCT02315703) is a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase I/IIa clinical trial investigating the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of various vaccine regimens containing Ad26.Mos.HIV (Ad26.Mos1.Env, Ad26.Mos1.Gag-Pol, Ad26.Mos2.Gag-Pol), MVA-mosaic (MVA.Mos1, MVA.Mos2) and gp140 protein (aluminum phosphate adjuvanted clade C gp140 Env protein) in healthy, HIV uninfected participants, considered at low risk for HIV infection. Following a 4-week screening period, eligible participants were randomized into one of eight study arms at 12 clinical sites. Participants were randomly assigned to one of eight treatment groups based on a computer-generated randomization code prepared before the study. The randomization was balanced by using randomly permuted blocks and stratified by region (US, Africa, and Asia). Enrollment in any one region was capped to ensure that a minimum of 50 subjects were enrolled from each region.

Participants and investigators remained blinded to treatment allocation throughout the study. The sponsor and the statistician were unblinded at the time of the primary analysis, which was conducted when all participants completed the Week 28 visit or discontinued earlier. IRB approvals and written informed consent were obtained.

Participants were primed at weeks 0 and 12 with Ad26.Mos.HIV and boosted at weeks 24 and 48 with Ad26.Mos.HIV with or without high dose (HD; 250 μg) or low dose (LD; 50 μg) of gp140 protein, or MVA-mosaic with or without high dose or low dose of gp140 protein, or gp140 protein alone (high dose) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. APPROACH and rhesus monkey study screening, enrollment, vaccination, termination and continuation.

Participants in the APPROACH study were randomized by region (US, Africa and Asia) into eight vaccine regimen groups. Groups 1–7 were administered prime immunizations with trivalent Ad26 followed by different boost immunizations: Ad26+gp140 HD, Ad26+gp140 LD, Ad26, MVA+gp140 HD, MVA+gp140 LD, MVA, gp140 HD, respectively. Group 8 received placebo for both prime and boost. 86% of participants received all four vaccinations, 92% of participants received the first 3 vaccinations, 4% of participants received only 2 vaccinations and 3% received only the first vaccination. The full analysis set (n=393) consisted of all participants who were randomized and who received at least one dose of study vaccine. This was the primary population for all analyses (except immunogenicity). The per protocol immunogenicity population (PPI [n=358]) consisted of all participants who received at least the first three vaccinations, according to the protocol-specified vaccination schedule (+/− 2 weeks), have at least one measured post-dose blood sample collected and were not diagnosed with HIV during the study. Week 50/52 samples from participants in the PPI population who missed the 4th vaccination or did not receive the 4th vaccination in the protocol-specified time window (+/− 2 weeks) were excluded from the analysis (Panel A). Rhesus monkeys were also randomized into regimens that consisted of two prime immunizations with Ad26, followed by boost immunization with either: Ad26, MVA, gp140 or a combination thereof. Rhesus monkeys were then challenged with SHIV-SF162P3, and viral loads determined by qualified viral load assay. All monkeys were correctly immunized and survived to the end of the study period (Panel B).

ENDPOINTS

Primary endpoints were safety and tolerability of the vaccine regimens and Env-specific binding antibody responses in each experimental group. The predefined timepoint for the primary analysis of safety and immunogenicity endpoints was week 28 (4 weeks after the third vaccination). Safety and immunogenicity was also assessed at the week 52 timepoint. Secondary endpoints included antibody effector function and cellular immune responses.

Local and systemic reactogenicity safety data were collected for 8 days after each vaccination. Unsolicited adverse events (AEs) were analyzed 28 days post-vaccination. Data on serious adverse events (SAEs) and incident HIV infections were collected during the entire study period (96 weeks). Blood samples for serum chemistry (creatinine, aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase), hematology and urinalysis were collected at several timepoints throughout the study. Baseline troponin was assessed at screening, and electrocardiogram measurements were assessed both at screening and prior to the first boost vaccination at week 24.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Sample size was determined to assess the safety and tolerability of the different vaccine regimens. The statistical analysis of safety data followed the intent-to-treat principle, including all participants that were randomized and received at least one vaccine dose (Ad26 or Placebo). For each vaccine regimen, the number and proportion of participants experiencing AEs, SAEs and laboratory abnormalities were tabulated, per dose and over the entire regimen.

Immunogenicity data were analyzed using the per-protocol immunogenicity population, comprising participants who received the first three vaccinations according to the protocol-specified vaccination schedule (+/− 2 weeks), and not diagnosed with HIV prior to the primary endpoint at week 28. Immunogenicity data were analyzed descriptively through tabulations of geometric mean with corresponding two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and/or medians, but no formal statistical comparisons were made. Response rates and CIs for immunoassays were calculated as the number and proportion of participants meeting the predefined definition of response. CIs were not adjusted for multiplicity.

RHESUS MONKEY CHALLENGE STUDY (NHP 13-19)

Seventy-two Indian-origin rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were immunized using a similar design as for the APPROACH clinical study, priming with Ad26.HIV.Mos at weeks 0 and 12, and boosting with various regimens at weeks 24 and 52 (12 monkeys per group, one placebo group), although only the high dose gp140 protein (250 μg) was tested in monkeys (Fig. 1B). This design allowed an evaluation of the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of these same vaccine regimens in monkeys. All monkeys then received six weekly intrarectal challenges with 500 TCID50 of the heterologous virus SHIV-SF162P3 starting at week 76, six months after completion of vaccination. Viral loads were determined weekly following challenge determined by a qualified viral load assay. Ad26 vectors and gp140 protein were produced at Janssen, the MVA vectors were produced at WRAIR, and the SHIV challenge stock was produced in rhesus PBMC at BIDMC. IACUC approvals were obtained.

Time-to-infection was analyzed with Cox proportional hazard regression for discrete times, and final infection status was assessed by two-sided Fisher’s exact test. Multiple comparison adjustments were performed for the vaccine groups with a five-fold Bonferroni adjustment.

To assess immune correlates of protection, assays (Supplemental Table 1) were selected stepwise from a predefined set by cumulative logistic regression on time-to-infection using groups Ad26/Ad26, Ad26/gp140 and Ad26/Ad26+gp140. The prediction model was more powerful without the groups boosted with MVA, likely related to the differential immune profiles of MVA vectors. Selection continued until no assay significantly (P<0.05) improved the model. For individual assays, Spearman correlations were calculated with time-to-infection (Supplemental Table 1).

RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHICS AND SAFETY IN THE APPROACH STUDY

The first participant was randomized on 24 February 2015, and the last subject was randomized on 16 October 2015. The last assessment used in the Week 52 analysis occurred on 20 October 2016. Overall, 393 participants were randomized and received at least one dose of study vaccine (Fig. 1A). At the week 52 analysis, 39 (9.9%) participants prematurely discontinued from the study (13 lost to follow-up, 12 withdrew, 3 following physician decision due to psychiatric issues, and 11 stated “other” reasons). Overall, 38% of the participants were randomized in the USA, 33% in Eastern Africa, 14% in South Africa and 15% in Thailand. Of all participants, 54% were male; 56% were Black or African-American, 27% White, 16% Asian and 1.5% listed “other” as race. Median age was 29 (range 18 to 50) years and median body mass index was 24.8 (range 15.6 to 51.8) kg/m2. No substantial demographic imbalances were seen between treatment groups (Supplemental Table 2) and no clear difference was seen between participants receiving active product versus those receiving placebo.

Detailed evaluation of the safety and tolerability profile is presented in the supplement (Supplemental Fig. 1; Supplemental Tables 3–6). During the 8-day post-vaccination period, the most commonly reported solicited local event was mild to moderate pain at the injection site (varying from 69% to 88% between the different active arms, post any dose, compared to 49% in the placebo arm). This generally decreased with subsequent vaccinations. Mild to moderate headache (46% to 65% in active arms), fatigue (44% to 70%) and myalgia (32% to 49%) were the most commonly reported solicited systemic events. Most AEs reported during the 28-day reporting period post each vaccination were mild or moderate severity. Five participants reported at least one grade 3 AE considered related to vaccine: abdominal pain and diarrhoea (in the same participant), increased aspartate transaminase, postural dizziness, back pain, and malaise (Supplemental Table 5). Overall, there was no remarkable difference in safety or tolerability/reactogenicity between the 7 different groups receiving vaccination. Additionally, one participant presented at the emergency department, 12 hours after receiving the first vaccination, describing signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction. Evaluation by the ER physician did not reveal signs indicative of an allergic reaction. The participant was discharged from the ER after receiving diphenhydramine, but without corticosteroids. He stated the episode resolved after 1 day. It was later discovered that the subject had a history of illicit drug use and bipolar disorder with hallucinations. This was considered a severe allergic reaction possibly related to the vaccine (Supplemental Table 5). Further vaccinations were discontinued. During the reporting period following each dose, no grade 4 AEs or deaths were reported. Three incidental HIV infections occurred at a single site in South Africa. Five more participants included in the week 52 analysis discontinued the study vaccination due to AEs; one was considered related to the study vaccination (grade 1 urticaria), and four as unrelated (grade 1 chronic kidney disease; grade 3 lumbar vertebral fracture; grade 3 intraductal proliferative breast lesion; grade 1 right bundle branch block). No safety concerns were identified following patient examination.

Overall, there was no remarkable difference in safety/tolerability of any of the 7 active vaccine groups, considering solicited and unsolicited AEs, AEs of grade 3 or grade 4, SAEs, and AEs leading to discontinuation.

IMMUNE RESPONSES IN THE APPROACH STUDY

All vaccine regimens were highly immunogenic. Binding antibody responses to autologous Env clade C gp140 were detected in all vaccinees following the second immunization at week 12 (100%; 95% CI, 93 to 100%). Responses were differentially boosted after the third vaccination at week 24 and fourth vaccination at week 48. After the week 24 vaccination, most groups maintained 100% antibody response (Fig. 2A). ELISA titers were higher in the groups that received the gp140 protein boost and were dependent on gp140 dose. Including either Ad26 or MVA vector in the boost also increased responses. Total IgG responses to cross-clade transmitted/founder Envs, to Envs isolated from chronically infected individuals, and to consensus Envs were similar to the autologous responses, demonstrating binding to multiple global Envs (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). A substantial number of subjects also showed responses to gp70-V1V2 antigens (Supplemental Fig. 3C). IgG subclasses were primarily IgG1 and IgG3, with minimal to no induction of IgG2 and IgG4 (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 2. APPROACH immune response to vaccination regimens.

All Panels show responder rates for each vaccine group for baseline (BL) and weeks post third and fourth vaccination (week 26 or 28, and week 50 and 52, respectively) beneath the graph. All groups (except for placebos) were primed twice with Ad26 vectors and then boosted with the regimens shown at the top of the graph. Vaccine response was defined as titer >threshold (if baseline is <threshold or is missing); otherwise, was a titer with a 3-fold increase from baseline (if baseline is ≥threshold). Humoral immune responses to each vaccine group were measured by ELISA and ADCP assays (Panel A and B), and cellular immune response was measured by ELISPOT assay (Panel C). In Panels, A and B the geometric mean titers (GMT) are shown beneath the data points. In Panel C, median spot forming units per million PBMC (SFU / 106 PBMC) are shown. The dotted horizontal line shows the threshold for each assay performed: lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for Panel A, and the limit of detection (LOD) for Panel B, and the 95th percentile (P95) of the overall baseline values in Panel C. Panel D shows the number of ELISPOT subpools with vaccine-induced T-cell responses for a subset of participants in Ad26/Ad26+gp140 LD and Ad26/MVA+gp140 LD vaccine groups, respectively. The dotted line shows the median number of subpools recognised. PBMC denotes peripheral blood mononuclear cells; Resp % is the percentage response, and SFU are spot forming units.

Antibody functionality was evaluated by ADCP assays (Fig. 2B) and correlated with the binding antibody responses (Supplemental Fig. 5). ADCP responses were generated in most vaccine recipients who received the protein boost, and the magnitude of responses increased with protein dose and presence of vector. In the Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HD boost group, 72% exhibited ADCP responses at week 28, and 80% at week 52. Serum neutralizing activity was only detected against easy-to-neutralize tier 1 HIV-1 variants (Supplemental Fig. 6; Supplemental Table 7).

High frequencies of cellular immune responses were detected by IFN-γ ELISPOT assays against Env PTEg peptide pools (Fig. 2C) as well as against vaccine-matched peptide pools29 (Supplemental Fig. 7). ELISPOT responses to Env peptide pools increased in groups that received the protein boost. In the Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HD boost group, 77% exhibited ELISPOT responses at week 26, and 83% at week 50. ELISPOT responses were also detected against Gag and Pol peptide pools (Supplemental Fig. 7). Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) for IFN-γ/IL-2 demonstrated that CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses were both generated; CD4 T-cells were directed primarily to Env while CD8 T-cells were directed primarily to Pol and to a lesser extent to Gag and Env (Supplemental Fig. 8).

Breadth of T-cell responses was assessed in 20 participants from Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HD and Ad26/MVA+gp140 HD groups after the first boost immunization by ELISPOT assays using PTEg and vaccine matched subpools consisting of 10 peptides. A median of 9 subpools were recognized in the Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HD group (range 6 to 28) and 10 in the Ad26/MVA+gp140 HD group (range 1 to 17), reflecting a conservative estimate of T-cell breadth induced by the vaccines (Fig. 2D).

Most individuals in sub-Saharan Africa had low-to-moderate titers of baseline Ad26-specific nAbs (Supplemental Fig. 9), consistent with previous epidemiologic surveys.23 These titers were substantially lower than Ad5-specific nAb titers in these populations.30 No associations were observed between baseline Ad26-specific nAbs prior to immunization and ELISA or ELISPOT responses following immunization, showing that these vector-specific antibody titers did not interfere with the vaccine immune response (Supplemental Fig. 10). Variability in immune response to vaccine stratified by gender, age, or region are shown in Supplemental Fig. 11.

PARALLEL IMMUNOGENICITY AND EFFICACY IN RHESUS MONKEYS

Seventy-two rhesus monkeys received one of five different vaccine regimens or placebo (12 monkeys per group, Fig. 1B). Binding antibody responses against clade C Env were detected in all vaccinated monkeys by ELISA (Fig. 3A), and regimens that included the protein boost exhibited substantially higher titers. Antibody titers declined from peak (week 54) to the day of challenge (week 76, Supplemental Fig. 12). Functional ADCP responses were detected after the heterologous boost immunizations (Fig. 3B) and correlated with binding antibody titers (Supplemental Fig. 5). Serum neutralization of tier 1A viruses was observed at the peak of the immune response, while serum neutralization titers for tier 1B viruses were low (Supplemental Fig. 13), and no neutralization of primary isolate-like tier 2 viruses was observed.

Figure 3. Immune response to vaccination regimens in rhesus monkeys.

All groups (except for placebos) were primed twice with Ad26 vectors and then boosted with the regimens shown at the top of the graph. Humoral immune responses to each vaccine group were measured by ELISA and ADCP assays (Panel A and B), and cellular immune response was measured by ELISPOT assay (Panel C). In Panels A and B, shown beneath the data points are the geometric mean titers (GMT) of binding antibody responses for each vaccine group at baseline (BL) and weeks post third and fourth vaccination (week 26 or 28, and week 54 and 56, respectively). In panel C, median spot forming units per million PBMC (SFU / 106 PBMC) responses are shown. In Panels A and C, the dotted horizontal line shows the lower limit of quantification. Vaccine response was defined as titer >threshold (if baseline is <threshold or is missing); otherwise, was a titer with a 3-fold increase from baseline (if baseline is ≥threshold). PBMC denotes peripheral blood mononuclear cells; Resp % is percentage response, and SFU are spot forming units.

Cellular immune responses against HIV-1 Env, Gag, and Pol were detected by IFN-γ ELISPOT assays using both PTEg peptide pools (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. 14) and vaccine-matched peptide pools (Supplemental Fig. 15). Regimens that included the MVA boost immunizations showed the highest mean ELISPOT responses. These trends were confirmed by frequencies of IFN-γ/IL-2 producing CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells enumerated by flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. 16).

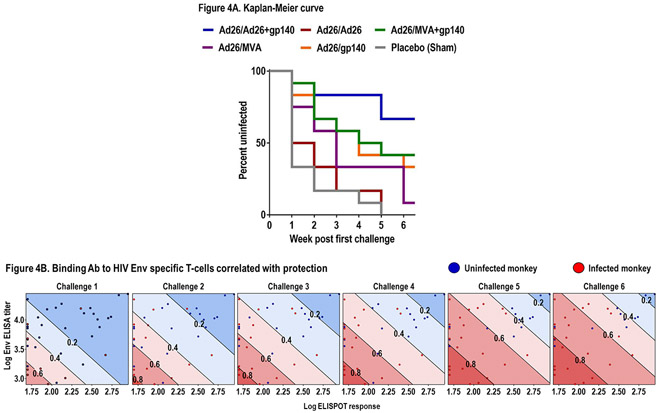

All animals were then challenged 6 times by the intrarectal route with the heterologous, tier 2 neutralization-resistant virus SHIV-SF162P3. Control monkeys were infected after a median of 1 challenge (range 1 to 5). The various vaccine regimens showed different degrees of protective efficacy, defined as reduced per exposure acquisition risk and reduced numbers of infected monkeys after the full series of challenges as compared with the control group. The Ad26/Ad26+gp140 regimen afforded the greatest protection, with 8 of 12 monkeys uninfected after the challenge series (Fig. 4A). This corresponded to a 94% reduction in per exposure acquisition risk (P=0.0002, log-rank test) and 66% complete protection (P=0.0067, 2-sided Fishers’ exact test). The other regimens showed lower point estimates of protection in this model.

Figure 4. Protection and correlates in rhesus monkeys.

Six weekly intrarectal challenges were administered to rhesus monkeys at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Panel A shows Kaplan-Meier plot of the level of protection each vaccine regimen offered to the 12 rhesus monkeys at risk, assessed one week after each challenge. No animals were censored. Panel B shows humoral and cellular immune response measured by clade C ELISA at week 28 and PTEg Env ELISPOT at week 26, the week following each of six challenges (at weeks 77–84) of monkeys from groups: Ad26/Ad26, Ad26/gp140, Ad26/Ad26+gp140. Blue dots represent pooled uninfected monkeys per timepoint, and red dots indicate pooled monkeys that were infected following each challenge. The diagonal lines display model-derived probabilities of infection, modeled on ELISA and ELISPOT responses.

Based on previously reported potential correlates of protection, we selected 18 humoral and cellular immunologic parameters (Supplemental Table 1) to generate an immune readout-based prediction model. Parameters were correlated with time-to-infection (Spearman correlation). An ordinal logistic prediction model with an optimal subset of these parameters was generated with stepwise selection of the best correlating parameters. The immune correlates model that best predicted time-to-infection included clade C ELISA and PTEg Env ELISPOT responses at week 28 (P=0.0007, model fit of both assays) (Fig. 4B and Supplemental Table 1), and the linear predictor defined with these two parameters strongly correlated with observed data (rho=0.55, Spearman correlation). None of the other immunologic measures significantly improved the predictive accuracy of this model once these two readouts were included.

COMPARISON OF CLINICAL AND PRECLINICAL IMMUNE RESPONSES

Given the parallel design of the studies in humans and rhesus monkeys, and the comparable performance of the clade C ELISA (Supplemental Fig. 17) and Env PTEg ELISPOT assays, we compared the vaccine-elicited immune responses in monkeys and humans (Fig. 5). The monkey and human ELISA data were compared for each immunization regimen, and ranking between regimens proved analogous for monkeys and humans (Fig. 5A). When antibody titers were compared longitudinally between species (Fig. 5B), similar kinetic profiles were observed with a slightly faster decrease of antibody titers in monkeys. A comparison of ELISPOT responses between monkeys and humans was less clear (Fig. 5C) and showed earlier induction of cellular immune responses in humans (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the ADCP (Fig. 2B, 3B) and ICS data (Supplemental Fig. 8 and 16) suggested similarities in antibody and T-cell functionality for both species. These data suggest substantial comparability in the magnitude, kinetics, durability, and phenotypes of immune responses induced by these vaccines in humans and monkeys.

Figure 5. Human and rhesus monkey data comparison.

Comparisons of the magnitude of immunological responses between rhesus monkey and human studies. Panels A and C display transformed rhesus monkey and human immunological responses to each vaccine regimen, by ELISA and ELISPOT assay data, respectively. Rhesus monkey ELISA data in panel A and B have been transformed to human ELISA units. Panel B shows longitudinal comparison of clade C gp140 ELISA data for Ad26+gp140 groups. Panel D shows comparisons of Env PTEg ELISPOT binding response between humans and monkeys at post third and fourth vaccinations in the Ad26+gp140 group. PBMC denotes peripheral blood mononuclear cells, SFU are spot forming units; data in panels A-C are represented as GMT ± SD.

To support the initiation of the phase IIb efficacy study, go/no-go criteria based on the immunologic correlates of protection identified in monkeys were established in advance (Supplemental Table 8). These criteria were set based on the frequency and magnitude of the cellular and humoral immune responses associated with protection in rhesus monkeys. Both the Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HD and Ad26/MVA+gp140 HD groups achieved these criteria, and the remaining regimens were down-selected. In particular, the regimens that included low dose or no protein did not generate sufficient ADCP responses to meet these criteria. A comparison of Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HD and Ad26/MVA+gp140 HD across humoral and cellular immune responses showed no superiority for either regimen. The higher point estimate of protective efficacy in rhesus monkeys as well as regimen simplicity and manufacturability favored selection of the Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HD regimen.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that mosaic Ad26-based vaccine regimens were well tolerated and induced robust humoral and cellular immune responses in healthy individuals in Eastern Africa, South Africa, Thailand and the USA. All vaccine regimens tested were safe and generally well-tolerated. There were no remarkable differences between the different active groups in terms of solicited or unsolicited AEs, including AEs of grade 3 or 4, SAEs, AEs leading to discontinuation or laboratory/ECG-related AEs. These vaccine regimens also elicited largely comparable immune responses in rhesus monkeys and afforded substantial protection against repetitive, heterologous, intrarectal SHIV-SF162P3 challenges. In both humans and rhesus monkeys, the optimal vaccine regimen included priming with Ad26 vectors expressing mosaic HIV-1 Env and Gag-Pol immunogens and boosting with the combination of Ad26 vectors and the high-dose Env gp140 protein. The immunogenicity data met pre-established go/no go criteria to initiate a phase IIb efficacy trial, called Imbokodo (HPX2008/HVTN 705; NCT03060629), which will evaluate the protective efficacy of this vaccine against acquisition of HIV-1 infection in 2,600 young women in southern Africa.

Previous HIV-1 vaccine candidates have typically been limited to specific regions of the world.11,13,14 Optimized mosaic antigens17,18 offer the theoretical possibility of developing a global HIV-1 vaccine. Cellular immune breadth induced by these mosaic Ad26-based vaccine candidates (median of 9 to 10 epitopes) was substantially greater than that reported previously for other Ad5-based and Ad26-based vaccines expressing natural sequence antigens (median of 1 epitope) (Supplemental Fig. 18).31,21 Therefore, responses to the mosaic vaccine may have enhanced potential to recognize circulating virus strains.32,33 While the mosaic antigens were initially designed to improve T-cell breadth, these immunogens also elicited cross-clade binding antibodies to several HIV-1 envelope antigens.

In rhesus monkeys, the statistical correlates of protection included antibodies against clade C Env as measured by ELISA and T-cell responses as measured by Env PTEg ELISPOT assays. These two parameters were combined into a linear predictor that correlated with protective efficacy in this animal model and formed the basis of the go/no-go criteria to advance the mosaic Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HIV-1 vaccine candidate into a clinical efficacy trial. We speculate that these immunologic parameters may be surrogate markers for actual protective immune responses, which likely involve functional antibody responses.26,27 The role of virus-specific T-cell responses in protecting against acquisition of infection remains to be determined.

The principal limitation of this study is that the relevance of vaccine protection in rhesus monkeys to clinical efficacy in humans remains unclear. As such, the preclinical challenge models may need to be refined when clinical efficacy data become available. Another limitation is a lack of knowledge of a true mechanistic correlate of protection against HIV-1 in humans. The statistical correlates identified in this study have practical utility, but further investigation is required to define the actual mechanisms of protection. Finally, these vaccine regimens did not induce broadly reactive nAbs.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that the mosaic Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HIV-1 vaccine was comparably and robustly immunogenic in humans and rhesus monkeys and showed substantial protective efficacy in monkeys. A phase IIb clinical efficacy trial has been initiated in southern Africa to determine whether this vaccine candidate will prevent HIV-1 infection in humans.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic Review:

A safe and effective HIV-1 vaccine will likely be required for a durable end to the HIV-1 pandemic. No licensed HIV-1 vaccine exists, and only four HIV-1 vaccine concepts have been evaluated for clinical efficacy to date. We developed a candidate HIV-1 vaccine consisting of priming with Ad26 vectors expressing bioinformatically optimized “mosaic” Env/Gag/Pol immunogens and boosting with Ad26 vectors and adjuvanted Env gp140 protein. We evaluated this vaccine as well as others in parallel preclinical and phase 1/2a clinical studies. We searched PubMed throughout the study for published HIV-1 vaccine studies in the medical literature as well as ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing HIV-1 vaccine clinical trials, and we found no evidence of prior testing of this vaccine candidate.

Added Value of This Study:

All vaccines that were tested in this study demonstrated favorable safety and tolerability in humans. The mosaic Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HIV-1 vaccine induced robust humoral and cellular immune responses in both humans and rhesus monkeys. Immune responses in humans and monkeys were similar in magnitude, durability, and phenotype. This vaccine provided 66% protection against acquisition of six intrarectal SHIV-SF162P3 challenges in rhesus monkeys.

Interpretation of the Totality of Data:

The mosaic Ad26/Ad26+gp140 HIV-1 vaccine met pre-established safety and immunogenicity criteria to advance into a phase IIb clinical efficacy study in sub-Saharan Africa, which is now underway.

Acknowledgments:

• Mark Feinberg (International AIDS Vaccine Initiative [IAVI]), James Kublin (HVTN), Mary Marovich (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease [NIAID]), Tina Tong (NIAID), Bruce Walker (Ragon Institute), and Julie Ake (Military HIV Research Program).

• Emilio Emini, Nina Russell, Peggy Johnston and colleagues at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

• Michael Pensiero, Dale Hu, and colleagues at the NIH HVTN Laboratory Center, Division of AIDS (DAIDS), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

• Janssen Extended Compound Development Team: Iedo Beeksma, Gabriel Faiman, Amy Kinney, Ad Knaapen, Yulya Nosovets, Valérie Oriol Mathieu, Maria Pagany, Sara Sprangers, Stefan Thoelen, John Trott, Claudia Koay Tulanowski, Kathleen Van Den Bulck, Richard Verhage, Ian Warden, Amanda Willms, and Olive Yuan.

• Additional acknowledgements: Ray Dolin, Mike Seaman, Stephen Walsh (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center), and Karina Yusim (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

• Laboratory Data Operations staff and colleagues at Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research and Prevention, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and laboratory staff and quality assurance unit at the Duke HVTN laboratory center.

• Medical writing support was provided by Katie Holmes of Zoetic Science, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, and was funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. All co-authors provided a full review of the article. The authors are fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved in all stages of manuscript development and have approved the final version.

Grants:

• Funded by Janssen Vaccines & Prevention B.V., the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and others; A004 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02315703

• NIH OD024917, AI068618, AI078526, AI096040, AI124377, AI126603, AI128751, TR001102

• Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard

• A cooperative agreement (W81XWH-07–2-0067) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., and the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD). Material has been reviewed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors, and are not to be construed as official, or as reflecting true views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

• IAVI with the generous support of USAID and other donors; a full list of IAVI donors is available at www.iavi.org. The contents of this manuscript are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

• Dan Barouch reports receipt of grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Janssen Vaccines & Prevention B.V. Dan Barouch is a co-inventor on HIV-1 vaccine antigen patents that have been licensed to Janssen Vaccines & Prevention B.V.

• Frank L. Tomaka, Frank Wegmann, Daniel J. Stieh, , Steven Nijs, Jeroen Tolboom, Jenny Hendriks, Zelda Euler, Maria G. Pau, Hanneke Schuitemaker are employees of Janssen, Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. Ludo Lavreys is a consultant to Janssen, Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson.

Trial registration number: NCT02315703

Role of Sponsor: Janssen participated in data collection, analysis, interpretation, and writing. The decision to submit for publication was joint among all co-authors. D.H.B., F.L.T., F.W., M.G.P., and H.S. had access to the raw data.

References

- 1.Gunthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2016 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 2016;316:191–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grabowski MK, Serwadda DM, Gray RH, et al. HIV prevention efforts and incidence of HIV in Uganda. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2154–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauci AS, Marston HD. Ending AIDS – is an HIV vaccine necessary? N Engl J Med 2014;370:495–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauci AS. An HIV vaccine is essential for ending the HIV/AIDS Pandemic. JAMA 2017;318:1535–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barouch DH. Challenges in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Nature 2008;455:613–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauci AS, Marston HD. Ending the HIV-AIDS pandemic – follow the science. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2197–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn NM, Forthal DN, Harro CD, Judson FN, Mayer KH, Para MF. Placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine to prevent HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:654–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitisuttithum P, Gilbert P, Gurwith M, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial of a bivalent recombinant glycoprotein 120 HIV-1 vaccine among injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet 2008;372:1881–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray GE, Allen M, Moodie Z, et al. Safety and efficacy of the HVTN 503/Phambili study of a clade-B-based HIV-1 vaccine in South Africa: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled test-of-concept phase 2b study. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:507–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer SM, Sobieszczyk ME, Janes H, et al. Efficacy trial of a DNA/rAd5 HIV-1 preventive vaccine. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2083–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2209–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath J, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1275–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomaras GD, Plotkin SA. Complex immune correlates of protection in HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials. Immunol Rev 2017;275,1:245–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, et al. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nat Med 2007;13:100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barouch DH, O’Brien KL, Simmons NL, et al. Mosaic HIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nat Med 2010;16:319–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbink P, Lemckert AA, Ewald BA, et al. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J Virol 2007;81:4654–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barouch DH, Picker LJ. Novel vaccine vectors for HIV-1. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014;12:765–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barouch DH, Liu J, Peter L, et al. Characterization of humoral and cellular immune responses elicited by a recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 HIV-1 Env vaccine in healthy adults (IPCAVD 001). J Infect Dis 2013;207:248–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baden LR, Walsh SR, Seaman MS, et al. First-in-human evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 HIV-1 Env vaccine (IPCAVD 001). J Infect Dis 2013;207:240–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baden LR, Karita E, Mutua G, et al. Assessment of the safety and immunogenicity of 2 novel vaccine platforms for HIV-1 prevention: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:313–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baden LR, Liu J, Li H, et al. Induction of HIV-1-specific mucosal immune responses following intramuscular recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 HIV-1 vaccination of humans. J Infect Dis 2015;211:518–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barouch DH, Liu J, Li H, et al. Vaccine protection against acquisition of neutralization-resistant SIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Nature 2012;482:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barouch DH, Stephenson KE, Borducchi EN, et al. Protective efficacy of a global HIV-1 mosaic vaccine against heterologous SHIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Cell 2013;155:531–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barouch DH, Alter G, Broge T, et al. Protective efficacy of adenovirus/protein vaccines against SIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Science 2015;349:320–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung AW, Kumar MP, Arnold KB, et al. Dissecting polyclonal vaccine-induced humoral immunity against HIV using systems serology. Cell 2015;163:988–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Malhotra U, Gilbert PB, Hawkins NR, et al. Peptide selection for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CTL-based vaccine evaluation. Vaccine 2006;24:6893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barouch DH, Kik SV, Weverling GJ, et al. International seroepidemiology of adenovirus serotypes 5, 26, 35, and 48 in pediatric and adult populations. Vaccine 2011;29:5203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janes H, Friedrich DP, Krambrink A, et al. Vaccine-induced gag-specific T cells are associated with reduced viremia after HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2013;208:1231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, et al. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nat Med 2007;13:100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdul-Jawad S, Ondondo B, van Hateren A, et al. Increased valency of conserved-mosaic vaccines enhances the breadth and depth of epitope recognition. Mol Ther 2016;24:375–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.