Abstract

Background & Aims:

Development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is associated with alterations in the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling pathway, which regulates liver inflammation and can have tumor suppressor or promoter activities. Little is known about the roles of specific members of this pathway at specific of HCC development. We took an integrated approach to identify and validate the effects of changes in this pathway in HCC and identify therapeutic targets.

Methods:

We performed transcriptome analyses for a total of 488 HCCs that include data from The Cancer Genome Atlas. We also screened 301 HCCs reported in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer and 202 from Cancer Genome Atlas for mutations in genome sequences. We expressed mutant forms of spectrin beta, non-erythrocytic 1 (SPTBN1) in HepG2, SNU398, and SNU475 cells and measured phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activity of SMAD family member 3 (SMAD3).

Results:

We found somatic mutations in at least 1 gene whose product is a member of TGFβ signaling pathway in 38% of HCC samples. SPTBN1 was mutated in the largest proportion of samples (12/202, 6%). Unsupervised clustering of transcriptome data identified a group of HCCs with activation of the TGFβ signaling pathway (increased transcription of genes in the pathway) and a group of HCCs with inactivation of TGFβ signaling (reduced expression of genes in this pathway). Patients with tumors with inactivation of TGFβ signaling had shorter survival times than patients with tumors with activation of TGFβ signaling (P=.0129). Patterns of TGFβ signaling correlated with activation of the DNA damage response and sirtuin signaling pathways. HepG2, SNU398, SNU475 cells that expressed the D1089Y mutant or with knockdown of SPTBN1 had increased sensitivity to DNA crosslinking agents and reduced survival compared to cells that expressed normal SPTBN1 (controls).

Conclusions:

In genome and transcriptome analyses of HCC samples, we found mutations in genes in the TGFβ signaling pathway in almost 40% of samples. These correlated with changes in expression of genes in the pathways; upregulation of genes in this pathway would contribute to inflammation and fibrosis whereas downregulation would indicate loss of TGFβ tumor suppressor activity. Our findings indicate that therapeutic agents for HCCs can be effective, based on genetic features of the TGFβ pathway; agents that block TGFβ should be used only in patients with specific types of HCCs.

Keywords: liver cancer, genetics, immune response, gene regulation, COSMIC

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) continues to rise at an alarming rate in the United States, and is the second leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.1, 2 The trend is reflective of a cohort infected by Hepatitis B and C (HBV and HCV) between the 1950s and 1980s, and prevalence is therefore likely to rise for at least the next decade.3 Yet, current chemotherapeutic regimens for the treatment of HCC are only partially effective. Curative therapies, including liver transplantation, surgical resection and radio frequency ablation are limited to only 10–20% of patients.4 Drug resistance is one of the causal factors for therapy failure, and is associated with the existence of tumor-like stem cells. Multiple studies have revealed etiological patterns and multiple genes/pathways signifying initiation and progression of HCC, including TERT, WNT-β-catenin, Tp53, HGF/c-Met, and VEGF/angiogenic signaling.5–7. Yet, patterns of mutations defining etiological factors (HBV, HCV, alcohol and others) 8 have yet to be definitively validated in a large cohort. Moreover, despite many advances in cancer genetics, we have not reached an integrated view of genetic mutations, copy number changes, driver pathways, and animal models that support effective targeted therapies HCC. Here, we analyze data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and combine the results with functional studies to dissect the components that identify specific temporal events that reflect the complexity of the TGF-β signaling pathway.

The TGF-β pathway is known to play a complex role in liver disease and liver cancer, where it exerts fibrogenic/pro-inflammatory, tumor suppressive, or pro-metastatic effects.4, 9–11 Mouse models provide important evidence for the dual roles of TGF-β during carcinogenesis. For example, animal models of mammary gland tumorigenesis support a pro-tumorigenic role for TGF-β signaling,12 while mouse models of gastrointestinal cancers such as colorectal cancer,13 HCC,14–17 and pancreatic cancer11 indicate a primarily tumor suppressive role for this signaling pathway. We recently discovered that our mouse models, which disrupts TGF-β signaling through combined partial loss of the SMAD adaptor Sptbn1 and Smad3 (Sptbn1+/−/Smad3+/−)on a C57B6 background, phenocopies a human stem cell disorder, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), associated with up to an 800-fold increased risk of tumorigenesis. In addition, up to 40% of TGF-β-deficient older mice spontaneously develop HCC.14, 18, 19 Patients with BWS can develop multiple tumor types within the same organ simultaneously, an example is the co-occurrence of a mesenchymal hamartoma, capillary hemangioma hepatoblastoma, and cholangiocarcinoma within the liver of a single patient.20 These events are suggestive of the multi-potentiality of neoplastic transformation and imply dysfunctional processes as stem cells differentiate into mature adult cell types.21 Yet, mechanistic insight into downstream effector pathways that lead to stem cell transformation, and an integrated analysis from mouse models to human disease for BWS and associated cancers remain ill-defined. The TGF-β-deficient Sptbn1+/−/Smad3+/− model suggests a potential “driver” role for the TGF-β pathway in suppressing HCC. However, such novel driver events are difficult to identify in human populations, since they occur in rare individual groups, raising challenges to drug development and the design of clinical trials.22 We present here the integrative analyses of a large number of open-access and new HCC cases, and provide new insights into the critical role of the TGF-β pathway in HCC development. Our analyses, which apprise a new approach analyzing cross talk between TGF-β pathway, pro-inflammatory pathway and DNA repair pathway, provide clinical significance and functional insight into the context-dependent role of TGF-β signaling in inflammation, cancer and genomic integrity.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples

Hierarchical clustering was performed in TCGA transcriptome sequencing database of 147 HCC cases. TGF-β signatures were validated with the following cohorts: 1) Additional 53 HCC cases from TCGA; 2) cohort GSE 14520 (225 HCC samples and 220 normal liver samples); 3) cohort GSE 14323 (55 HCC samples and 20 normal liver samples) from NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO); 4) transcriptome sequencing of four pairs of matched normal liver tissue and HCC samples obtained from the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (9194-N/T, 9401-N/T, 9195-N/T, and 9128-N/T), and four human HCC tumor samples (TP2, TP3, TO301, TP504) obtained from Georgetown University School of Medicine (GUSM).

We screened for mutations in whole-exome/genome sequencing of 202 HCC TCGA cases and 301 HCC cases reported in the COSMIC. The study was approved by the Office of Human Subjects Research of the NIH, GUSM and MDACC, and all samples were de-identified. Whole-genome sequencing was performed by Complete Genomics and analyzed at MDACC DNA core facility. TCGA liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) mutation and transcriptome RNA sequencing (bam files) and their related clinical data were obtained from the Cancer Genomics Hub (CGHub, https://cghub.ucsc.edu/) and TCGA Data Portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). The paired-end FASTQ files for each sample were extracted from bam files using bam2fastq (http://www.hudsonalpha.org/gsl/information/software/bam2fastq). Detailed methods of whole genome sequencing, characterization of TGF-β signaling in HCC, identification, and functional validation of SPTBN1 mutation is in supplementary information and available online.

Results

TCGA Analysis of HCC Patients Reveals Distinct Clusters Within the TGF-β Signaling Pathway; Inactivation of the TGF-β Pathway at the Transcriptomic Level is Associated with Poor Outcome

Previous reports demonstrate alterations of several TGF-β members and their target genes in liver and biliary cancers.10, 14, 23, 24 We studied the effect of disruption of the TGF-β pathway in HCC, both at the transcriptomic as well as the genomic level and validated our findings. We analyzed RNA sequencing data for the first group of 147 human LIHC patient samples, and 50 normal adjacent liver samples (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively) and found that genes directly associated with the TGF-β family were recurrently dysregulated (i.e. either elevated or suppressed compared to normal, TGFB1 (30%), SMAD3 (54%), SMAD4 (41%), the SMAD3 adaptor, SPTBN1 (27%) (Figure 1A).14 Whereas normal hepatocytes do not express TGFB1, many HCCs and their surrounding stromal cells do, implying that TGF-β signature presented in our study may reflect both primary liver tumors as well as the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 1.

Disruption of TGF-β signaling and major signal transduction pathways in HCCs. (A) Clustering of transcriptomic data from 147 HCC samples from TCGA reveals 4 clusters. Clusters A and B demonstrate upregulation of TGF-β pathway genes (activated) to varying extents, whereas cluster D shows downregulations of the pathway genes (inactivated) and cluster C exhibit least disruption of the TGF-β pathway. The percentage of patients in which a gene is elevated or suppressed is given, showing the high frequency with which the TGF-β pathway is disrupted. (B) Box plot showing the TGF-β pathway activity scores for each sample in the four clusters and for normal liver samples. The plot shows that clusters “A”, “B” and “C” have varying extents of activation of the pathway compared to normal, whereas cluster “D” has inactivation of the pathway with a lower than normal score. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the four clusters indicates the “inactivated” cluster leads to a poor outcome. (D) Assembling the 2 clusters A and B into one group (the “activated” cluster) and comparing against the “inactivated” group (the inactivated cluster D) shows statistically significant survival differences (HR = 2.586, P= 0.0129).

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the data revealed four distinct TGF-β pathway clusters (“A” to “D”) (Figure 1A). Each cluster had a unique signature. Cluster “A” exhibited highly elevated levels of the 18 genes, indicating a highly activated TGF-β pathway. Clusters “B” also expressed elevated levels but to a lesser extent than cluster “A”, whereas we observed elevated levels of fewest genes in cluster “C” similar to normal samples, indicating gradual gradation in the activation level of the pathway from cluster “A” to cluster “C”. Cluster “D” was particularly interesting because it exhibited suppression of most of the genes, indicating a suppressed TGF-β pathway. Figure 1B depicts box plots of the overall TGF-β pathway activation levels for the four clusters compared to the normal samples, further clarifying their inter-relationships.

Interestingly, Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Figure 1C) identified patients in the inactivated cluster “D” displaying the poorest overall survival (OS), suggesting that patients with suppressed TGF-β pathway activity have poor prognosis, most likely due to the loss of the TGF-β tumor suppressor function. Furthermore, there was a tendency for patients in cluster “C”, the cluster with the least disruption of the TGF-β pathway, to do better than the other clusters, suggesting that nondisruption of the TGF-β pathway is probably better than either activation or inactivation of the pathway. Next, to directly compare activated vs. inactivated clusters, we assembled the 2 activated clusters A and B into one group (named the “activated” cluster), and compared its outcome with the inactivated cluster D (named the “inactivated” cluster). We observed a statistically significant difference in outcome between the “activated” vs. the “inactivated” group (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 2.586, log-rank test P-value = 0.0129) (Figure 1D). To elucidate the survival effects from other clinical characteristics of the patients in TCGA cohort, we parsed the TCGA data set with clinical characteristics including stage, adjacent hepatic inflammation, patient AFP levels, resection status, etiology, age, gender and race. Univariate analyses were performed to assess the association between TGF-β signature and OS for all patients and within each subgroup of patients defined by the demographic or clinical factor sub-categories (Table 1). The data suggest that the subgroup of patients with the TGF-β inactivated signature had a shorter OS than patients with TGF-β activated signature.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Survival of Patients With HCC on TGF-β Signature

| TGF-β

signature |

“Activated”

(A) |

“Inactivated“

(I) |

“Normal”

(N) |

P |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects |

Dead (%) |

Median (mon) |

Dead (%) |

Median (mon) |

Dead (%) |

Median (mon) |

Log-rank

test, Mantel-Cox |

|||||||

| n | n | n | A vs I | A vs N | I vs N | |||||||||

| Overall | 126 | 75 | 38 (51) | 38.3 | 24 | 16 (67) | 20.0 | 27 | 13 (48) | 59.7 | .0129a | .2873 | .0073 | |

| Stage | I | 48 | 27 | 10 (37) | 52.0 | 9 | 6 (67) | 16.1 | 12 | 5 (42) | 71.0 | .4224 | .0628 | .0163a |

| II | 28 | 16 | 4(25) | 106.8 | 5 | 2 (40) | 20.7 | 7 | 3 (43) | 108.6 | .124 | .4612 | .2243 | |

| III+IV | 40 | 26 | 11 (42) | 49.7 | 10 | 8 (80) | 20.9 | 4 | 4 (100) | 33.1 | .0945 | .94 | .647 | |

| Adjacent hepatic inflammation | None | 44 | 23 | 9 (39) | 99.9 | 12 | 8 (67) | 19.3 | 9 | 5 (56) | 85.5 | .0016a | .453 | .0014b |

| Mild + Severe | 37 | 24 | 11 (46) | 33.5 | 7 | 5(71) | 14.3 | 6 | 2 (33) | 45.7 | .0741 | .5514 | .0771 | |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | <300 | 67 | 37 | 18 (49) | 52.0 | 14 | 9 (64) | 20.9 | 16 | 8 (50) | 95.0 | .0503 | .1731 | .0185a |

| >300 | 28 | 19 | 9(47) | 30.0 | 6 | 4 (67) | 31.0 | 3 | 0 (0) | .4245 | .8137 | 1 | ||

| Resection | R0 | 100 | 62 | 23 (37) | 52.0 | 19 | 13 (68) | 20.4 | 19 | 9 (47) | 71.0 | .001b | .4424 | .0015b |

| R1+R2 + Rx | 20 | 15 | 11 (73) | 23.6 | 4 | 3 (75) | 37.5 | 1 | 1 (100) | .353 | .0287 | .0455 | ||

| Etiology | HCV | 16 | 11 | 5 (46) | 38.3 | 4 | 2 (50) | 14.6 | 1 | 0 (0) | .1941 | .6459 | .3621 | |

| HBV | 15 | 10 | 3 (30) | 44.0 | 1 | 1 (100) | 4 | 2 (50) | 54.1 | .1127 | .9192 | .0455a | ||

| Alcohol | 30 | 18 | 9 (50) | 47.4 | 8 | 5 (63) | 20.0 | 4 | 0 (0) | .2706 | .1017 | .0672 | ||

| Age | <65 | 64 | 46 | 20 (44) | 52.0 | 13 | 9 (69) | 20.0 | 5 | 1 (20) | .0313a | .1529 | .0357a | |

| >65 | 60 | 35 | 17 (49) | 37.8 | 11 | 7 (64) | 23.2 | 14 | 8 (57) | 71.0 | .4724 | .3003 | .0865 | |

| Gender | Male | 83 | 46 | 18 (39) | 27.9 | 19 | 12 (63) | 18.2 | 18 | 6 (33) | 54.1 | .1494 | .2578 | .0774 |

| Female | 52 | 36 | 19 (53) | 49.7 | 7 | 4(57) | 26.0 | 9 | 7 (78) | 71.0 | .191 | .9425 | .2537 | |

| Race | White | 89 | 55 | 28 (51) | 40.3 | 16 | 8 (50) | 21.4 | 18 | 9 (50) | 74.8 | .173 | .2749 | .0641 |

| Asian | 31 | 23 | 8 (35) | 54.1 | 4 | 3 (75) | 7.4 | 4 | 1 (25) | .211 | .4486 | .1714 | ||

| Others | 9 | 6 | 4(67) | 38.3 | 2 | 1 (50) | 17.2 | 1 | 0 (0) | .9835 | .6831 | 1 | ||

< .05.

< .01, significant, based on log-rank test P values.

Next we validated the signatures of the 4 clusters in three independent cohorts: (1) an independent set of 53 samples from TCGA (Supplementary Figure 1A); (2) cohort GSE 14520 from NCBI’s GEO website containing 225 HCC samples and 220 normal liver samples 25 (Supplementary Figure 1B); (3) cohort GSE 14323 from GEO with 55 HCC samples and 20 normal liver samples 26 (Supplementary Figure 1C). Hierarchical clustering was performed on all three validation sets and we observed a similar signature of “activated”/”normal”/ “inactivated” clusters (Supplementary Figure 1) in all data sets.

Finally, we identified a signature for “activated” and “inactivated” clusters and applied it to a fourth validation set consisting of a small cohort of 8 HCC samples (Supplementary Tables 3, 4), which we subsequently used for functional validation studies. The 8 samples also illustrate the “activated” vs. “inactivated” signatures (Supplementary Figure 1D). To date, we were able to validate our “activated”/”inactivated” groups in 4 independent cohorts consisting of a total of 341 HCC samples, with whole genome sequencing in a total of 206 HCC samples (Supplementary Figure 2).

Disruption of the TGF-β Pathway is Associated with Dysregulation of Several Potentially Targetable Oncogenes

We also investigated the relationship of various well-known oncogenic genes in HCC with the two signature groups of the TGF-β pathway (Figure 2A; Supplementary Data 2). The majority of these, including KRAS, MDM2, MTOR, IGF2 and VEGFA are highly expressed in the “activated” signature, suggesting association with tumor-promoting function of TGF-β signaling-potentially through active inflammation and/or EMT, and may reflect future targets in this context. In addition, the “activated” signature in TCGA data are consistent with a recent study demonstrating inhibition of TGF-β signaling either through overexpression of SMAD7 or SMAD2/3/4 knockdown and promotes HCC in the context of loss of p53. We observe that MDM2 levels (negative regulator of p53) are raised in the “activated” TGF-β signature (Figure 2A, p=0.0337).27 Interestingly, we found that a few oncogenic genes such as GDF15, HSPB1, HRAS and KEAP1 were significantly elevated in the “inactivated” signature. KEAP1 is well known as a negative regulator of nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a transcriptional factor that protects liver from oxidative stress induced liver injury.28 Elevated KEAP1 in TGF-β inactivated signature may promote HCC progression through suppression of cellular anti-oxidant defense by inhibiting NRF2-mediated liver protective genes.28, 29 Our TCGA data supports these dual effects of TGF-β signaling in HCC in a context-dependent manner. While the biological mechanisms of these associations are likely complex, these nine oncogenic genes could be potential targets in the context of disrupted TGF-β signaling in HCC (Figure 2A).

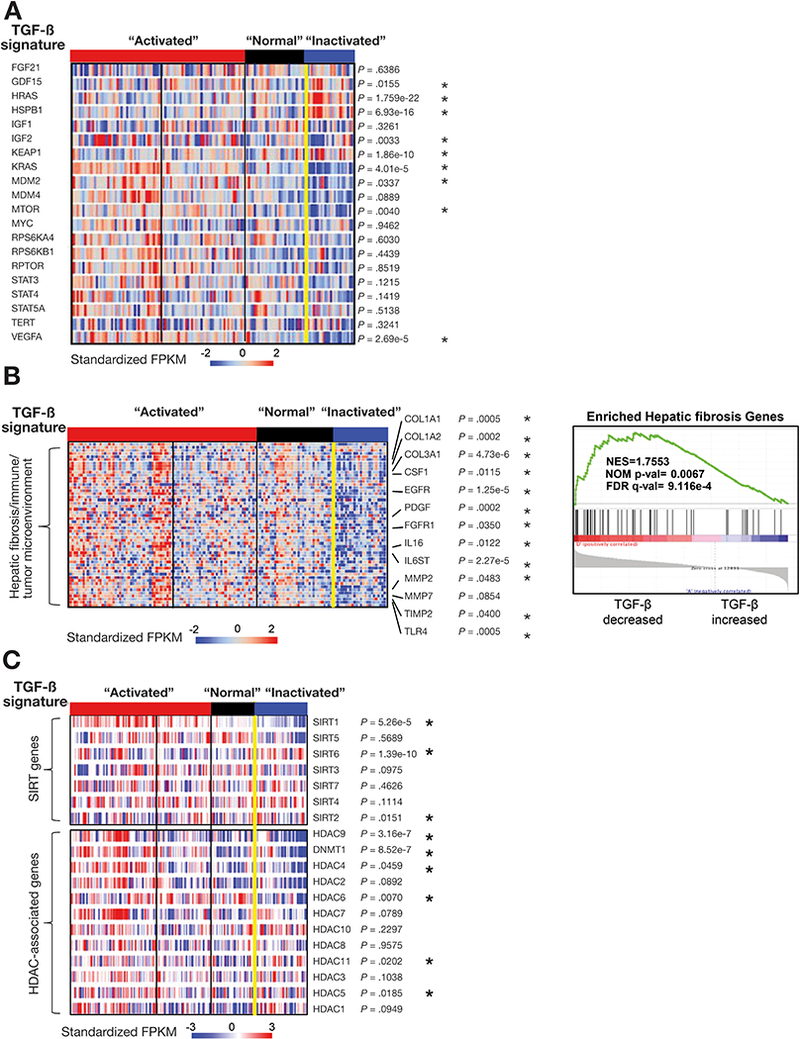

Figure 2.

Disruption of the TGF-β pathway is associated with other signaling pathways in HCC. (A) Disruption of the TGF-β pathway is associated with potentially targetable genes. (B) TGF-β pathway is associated with hepatic fibrosis/immune/tumor microenvironment-associated genes and DNA repair genes. We applied GSEA to compare enriched expression of hepatic fibrosis/immune/tumor microenvironment-associated genes (53 genes) with TGF-β signatures (right panels). (C) Disruption of the TGF-β pathway is associated with sirtuin and HDAC family genes. “*” represents genes with p values that are significantly altered in the TGF-β inactivated signature versus other clusters, based on t-tests with Banjamini-Hochberg (BH) corrections for multiple hypotheses testing.

TGF-β Pathway is Associated with Hepatic Fibrosis/Immune/Tumor Microenvironment-Associated Genes as well as the Sirtuin and Histone Deacetylases (HDAC) Family Genes

We further investigated any potential correlation between the dysregulated TGF-β superfamily genes and genes associated with hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, inflammation and cancer including p53/cell cycle genes as well as sirtuins and HDACS. We performed supervised clustering on 53 genes related to hepatic fibrosis/immune/tumor microenvironment as determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis in the cohort of 147 TCGA HCCs with “activated” and “inactivated” groups of the TGF-β pathway (Figure 2B). We found that elevated levels of genes regulating collagen synthesis (COL1A1/2), growth factors (EGFR, PDGF), cytokines (IL16, IL6ST), and matrix metalloproteases correlated significantly with the “activated” signature of the TGF-β family, suggesting that the “activated” signature reflected a response from hepatic tumor immune/microenvironment and fibrotic systems (overall correlation coefficient (ORC) = 0.42 and P=0.0001) (Supplementary Data 2 shows P-values for individual genes).

Analyses of the transcriptome of TCGA HCC patients also revealed a strong correlation between aberrant sirtuin and HDAC expression levels with abnormalities in the TGF-β pathway (Figure 2C). sirtuins such as Sirt6 and Sirt1 are NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases that act as chromatin silencers to regulate gene expression, DNA recombination, genomic stability, and aging and have previously been linked to liver diseases and HCC.30, 31 Liver-specific Sirt1 knockout mice develop hepatic steatosis and hepatic inflammation, and we found that Sirt1 expression tightly correlated with the activity of the TGF-β pathway (P=4.96e-05) (Figure 2C). We next analyzed Sirt1–6 expression in our TGF-β mutant cells to verify the link between “inactivated” TGF-β signature and dysregulation of sirtuins. Surprisingly, we observed significantly decreased levels of SIRT1 protein but not mRNA levels in Sptbn1 and/or Smad3 deficient MEFs and liver cancer cells (Supplementary Figure 3A-D), suggesting a post-transcriptional regulation of Sirt1 by TGF-β. Sirt3–6 transcript levels are decreased in Smad3+/−Sptbn1+/− MEF cells (Supplementary Figure 3A). Interestingly, SIRT6 RNA and protein levels are also decreased in cells with TGF-β deficiency (Supplementary Figure 3A, 3E). Moreover, Sirt6−/− mice develop chronic liver inflammation at an early age and eventually develop HCC (Supplementary Figure 4). Additionally, inspection of cBioPortal cancer genomics data reveal a correlation of poor prognosis with reduced Overall Survival (OS) for patients with decreased SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3 or SIRT6 together with loss of SPTBN1 (Supplementary Figure 5). Taken together, these results suggest that sirtuins and TGF-β pathway members may synergistically interact to suppress the multiple phases of HCC.

Disruption of the TGF-β Pathway is Associated with DNA Repair Pathways Both at the Transcriptomic Level and the Genomic Level

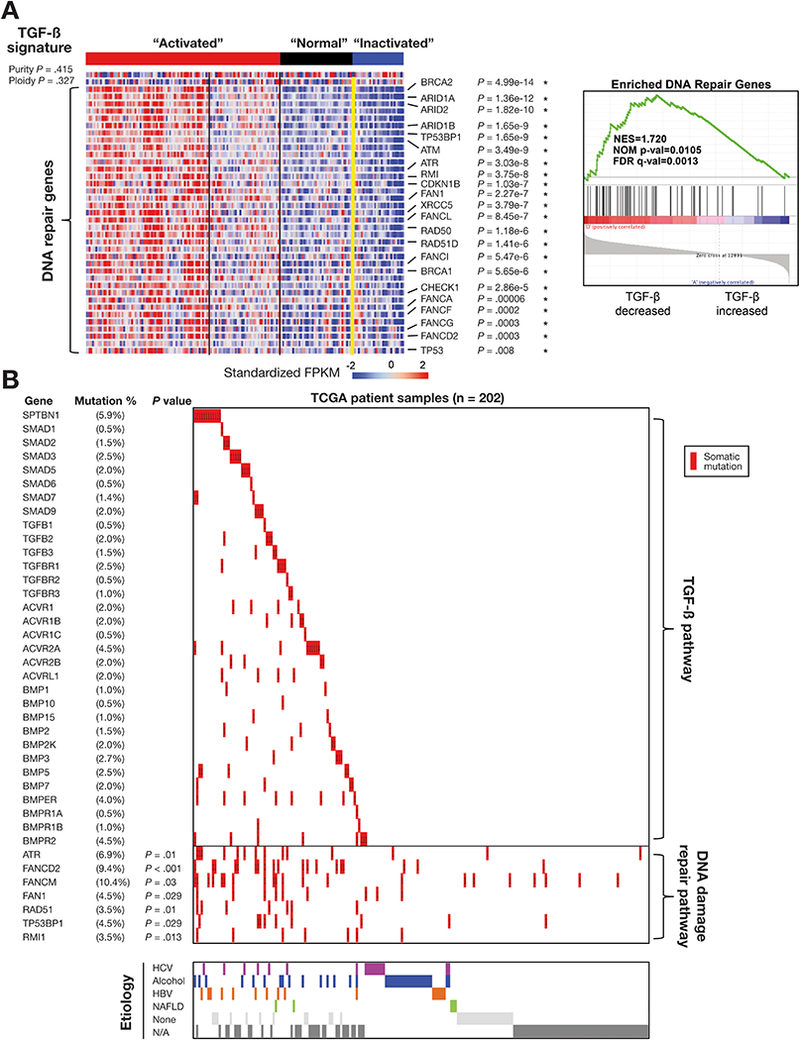

Perhaps the most striking correlation we observed in the TCGA data was between TGF-β signaling and DNA repair pathways, including the Fanconi anemia genes (Figure 3). The TGF-β “inactivated” signature was significantly associated with loss of tumor suppressor genes such as ATM, BRCA1 and FANCF that are involved in DNA damage repair (Figure 3A) (ORC = 0.58 and P = 0.0001) (Supplementary Data 2). The same correlations were also observed in the other four cohorts (Supplementary Figure 1), further strengthening our results.

Figure 3.

Association of somatic mutations of TGF-β genes with DNA damage repair genes. (A) Disruption of the TGF-β pathway is associated with DNA repair pathway genes. We applied GSEA to compare enriched expression of DNA repair genes (41 genes) with signatures (right panels). (B) Landscape of somatic mutations and HCC etiologic factors in the TGF-β pathway genes in 202 TCGA HCC samples. The percentages of samples with mutations in a given gene are shown. Purity and ploidy do not show a statistically significant association with the clusters (p value is based on t-tests without BH corrections).

To determine whether the association between TGF-β pathway genes and DNA repair pathway genes also occurred at the genomic level, we used somatic mutation data from a cohort of 202 TCGA samples for our analysis (Figure 3B; Supplementary Figure 6; Supplementary Table 5). We observed a maximum incidence of somatic mutations (9–10 %) in the FANCM and FANCD2 parallel to the mutations in TGF-β pathway genes. Overall, 77 of the 202 samples (38%) showed somatic mutations in at least one of the 32 TGF-β pathway genes studied, highlighting the prevalence of genomic aberrations of this pathway in HCCs. SPTBN1 was the single most mutated gene at 6% (12 out of 202 samples). Interestingly, mutations in several of the DNA repair pathway genes (ATR, FANCD2, TP53BP1) were found to be significantly associated with mutations in at least one of the TGF-β pathway genes (Figure 3B) (P < 0.05). However, we were unable to discern any statistically significant correlation between the mRNA expression and somatic mutations within the DNA repair pathway and the TGF-β pathway genes (Supplementary figure 7). Mutations of both TGF-β pathway genes and DNA repair genes do not always result in inhibition of mRNA levels, and may lead to increased expression, and potentially new and complex oncogenic function.

Consistent with the association that we observed for the mutations in genes of TGF-β pathway and DNA repair pathway, SMAD3 and SMAD4 have previously been identified as regulators of Fanconi genes.32, 33 Similarly, SPTBN1, by virtue of its involvement in SMAD3/4 localization and subsequent activation of SMAD3/4, regulates FANCD2 as well.34 Loss of SPTBN1 leads to decreased FANCD2 levels and SPTBN1-deficient cells are hypersensitive to DNA crosslinking agents that can be rescued by ectopic FANCD2 expression. Taken together, these studies implicate a critical role of TGF-β signaling in maintaining genomic stability potentially through modulation of the Fanconi anaemia pathway at interstrand cross links and prevent DNA damage from environmental agents such as alcohol.34

We further analyzed TCGA HCC for mutations and transcriptomic signature of TGF-β signaling that would validate previous studies on HCC etiology factors (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, Figure 3A).8 As with the main TCGA analyses we were unable to link transcriptomic signatures to HBV, HCV, alcohol or other HCC risk factors (Figure 3B; Table 1; Supplementary Figures 6 and 8).

The Role of SPTBN1 (D1089Y) in HCC

We previously established a genetic model of liver malignancy with loss of TGF-β signaling, the SPTBN1 heterozygous null mouse, in which more than 40% of the animals spontaneously develop HCC.14, 16, 19 In view of the high frequency of SPTBN1 mutations (6%) in human HCC (Figure 3B) and the mouse genetic data revealing its tumor suppressor role as a SMAD3 adaptor in HCC, we focused on somatic mutations in SPTBN1 and its functional validation. Whole genome sequencing was performed on our own cohort of 4 additional samples: 9194-N/T, 9401-N/T, 9195-N/T, and 9128-N/T, three of which were associated with HCV infection and one with both HCV and elevated alcohol consumption (Supplementary Figure 9; Supplementary Table 4; Supplementary Data 3–7). All four samples revealed mutations in at least one of the TGF-β pathway genes (Figure 4A-C; Supplementary Data 3–7). A novel somatic heterozygous missense mutation, D1089Y, in SPTBN1 (Figure 4A-C) was observed in the sample associated with both HCV infection and heavy alcohol intake, 9194-N/T.

Figure 4.

Identification of a novel and potential cancer driver mutation of SPTBN1 in HCC. (A) Circos plots of HCC sample 9194-N/T. Circos plot was drawn using the data generated from the paired (normal-tumor) samples. The chromosomes are presented in circular arrangement demarcated by megabase (Mb), scale on the outer ring are in a clockwise direction. The different tracks (from outside to inside): Gene symbols for impacted genes; density plot of somatic variants (blue); the called levels for the copy number variation (CNV) (grey); the lesser allele fraction (LAF) used to determine the CNV (light green); loss of heterozygosity (green dots); density of heterozygous SNPs (orange); density of homozygous SNPs (blue); inter-chromosomal translocation (orange). (B) Identification of a novel somatic mutation of SPTBN1 (c.G3219T; p.D1089Y) in an alcohol- and HCV-associated HCC. (C) All 4 HCC samples demonstrate somatic mutations in TGF-β pathway genes including a mutation in SPTBN1 gene. (D) Plot of all the mutations observed in SPTBN1 gene from TCGA, COSMIC and one of our own samples. Most of the mutations, including D1089Y, occur in the spectrin repeat domain. (E) The aberrations of DNA copy numbers of four of the HCCs. (F) Representative amplified genes and loss of heterozygosity genes in case 9194-N/T, 9128-N/T, 9195-N/T and 9401-N/T. (G-H) Electrostatic based colored molecular surface of the D1089Y mutant (G) and wt (H) of the spectrin repeat 8. Molecular surfaces are color-coded based on the electrostatic potential (red: negative, blue: positive and white: neutral).

An unbiased analysis of cases reported in the COSMIC indicates that somatic mutations occur in SPTBN1 in multiple human cancers (Figure 4D; Supplementary Tables 5–6; Supplementary Data 7–8). In total we identified 12 mutations in SPTBN1 from TCGA, the 2 mutations from COSMIC, and 1 mutation from our own set for liver cancers (Figure 4D) (D1089Y). Interestingly, the 9194-N/T tumor sample harboring SPTBN1-D1089Y mutation bore more aberrations of DNA copy numbers than the other three tumor samples (Figure 4E). These aberrations included gain of copy number in many oncogenic genes, such as MYC and TERT as well as loss of heterozygosity in tumor suppressors such as TP53 (Figure 4F).

Further analysis included homology-based structural modeling was performed to predict the functional consequence of these mutations. We generated a 3D homology model for spectrin repeat 8 that contains the D1089Y mutation. Interestingly, comparison of sequences of all 17 spectrin repeats in human SPTBN1, revealed that the sequence 1083-TAIASEDM-1090 in the repeat 8 is unique. The molecular surfaces of energy minimized models generated are depicted in Figure 4G-H (see supplementary methods) for mutant D1089Y (Figure 4H) and wild type (wt) D1089 (Figure 4G) for SPTBN1 repeat 8. Molecular surfaces are color-coded based on the electrostatic potential (red: negative, blue: positive and white: neutral). With the D1089Y mutation, the molecular surface of the mutant is more positive compared to wt because of the loss of negatively charged amino acid (D). In addition, the side chain of D1089 in wt makes a strong salt bridge with K1099 and a favorable hydrogen bond with Q1103. These interactions render this region of the structure rigid. In the D1089Y mutant, these interactions are lost and could lead to a more flexible structure. We predict that the surface presented by the D1089Y mutant is electrostatically different and less rigid, therefore, potentially destabilizing the protein-protein interactions. We further analyze other SPTBN1 somatic mutations with high DNA copy number alterations such as G562C and A1220V which locates in different spectrin repeat domains. However, no significant structural alterations were predicted by structural modeling studies on these mutants (Supplementary Figures 10–11; Supplementary Table 7). We, therefore, proceeded with further biological validation of D1089Y mutant.

SPTBN1 Somatic Mutation D1089Y Leads to Disruption of TGF-β/ SMAD3 Signaling in HCC

Previously we have demonstrated that SPTBN1 co-localized with SMAD3 in HepG2 cell nuclei after TGF-β treatment (Figure 5A) and both full-length SPTBN1 (Figure 5B) and SPTBN1 middle fragment (SPTBN1-Mid-wt) (residues 687aa-1543aa) bound to SMAD3 (Figure 5C). Here we observe that ectopic expression of the SPTBN1-Mid-wt, but not the middle fragment of the D1089Y variant (SPTBN1-Mid-D1089Y) or the N-/C-terminal of SPTBN1, restored TGF-β-induced SMAD3 nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity in these cells (Figure 5D, E; Supplementary Figure 12). Interestingly, even though the SPTBN1-Mid-D1089Y mutant translocated into the cell nucleus after TGF-β treatment, it could not induce SMAD3 nuclear translocation or TGF-β target gene activation (Figure 5D, bottom panels), suggesting that this mutation altered SMAD3 binding to SPTBN1 with loss of activity. Indeed, we found that the D1089Y mutation prevented SPTBN1 interaction with SMAD3 (Figure 5F). We also measured TGF-β–dependent phosphorylation of SMAD3. Expression of SPTBNl-Mid-wt augmented TGF-β–dependent phosphorylation, while SPTBN1-Mid-D1089Y expression attenuated such effect (Figure 5G). Our results suggest that SPTBN1, particularly the D1089 was important for the SMAD3 response to TGF-β signaling and downstream transcriptional activity (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

Disruption of TGF-ß/ SMAD3 signaling in HCC by somatic mutation D1089Y of SPTBN1. (A) TGF-β induced co-localization of SPTBN1 and SMAD3 in the HepG2 cell nucleus. HepG2 cells were treated with or without 200pM TGF-β for 2 hours. Immunofluorescent labeling detects endogenous SPTBN1 and SMAD3. Scale bars, 20 μm. (B-C) SMAD3 interacts with ectopic full-length SPTBN1 (B) and central domain of SPTBN1(C). HepG2 cells were co-transfected with the indicated plasmids. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Flag antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-V5 antibody. Schematic diagram shows the point mutation D1089Y in SPTBN1(C). (D) Overexpression of wt SPTBN1, but not SPTBN1-D1089Y mutant, rescued TGF-ß-induced SMAD3 nuclear translocation in SNU398 cells. The cells were transfected with Myc-SPTBN1-Mid-wt or Myc-SPTBN1-Mid-D1089Y for 24 hours, then treated with TGF-β for 2 hours. Scale bars, 20 μm. (E) Wt SPTBN1, but not the SPTBN1-D1089Y mutant, activated SMAD3 transcriptional activity in a TGF-β-dependent manner. A luciferase reporter containing SBE (4×SBE) was transfected with indicated plasmids into SNU398 cells (*P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA). (F) SPTBN1 bearing D1089Y mutation does not bind to SMAD3 in HepG2 cells co-transfected with indicated plasmids. (G) The SPTBN1-D1089Y mutation decreased the phosphorylation of SMAD3 upon TGF-β treatment in HepG2. (H) Proposed model of the critical role of SPTBN1 for SMAD3 activity responding to TGF-β.

Somatic Mutation D1089Y Leads to Loss of SPTBN1 Tumor Suppressor Function

Our previous findings (Figure 2C and 3A) suggested that TGF-β superfamily genes may play a critical role in DNA damage response. To determine the function of SPTBN1 mutant in DNA damage repair, SPTBN1 reconstitution experiments were performed in SNU398 cells followed by cell viability assay upon DNA crosslinking agents Mitomycin C (MMC), Cisplatin or ionizing irradiation (γIR). Ectopic expression, SPTBN1-Mid-D1089Y but not SPTBN1-Mid-wt, dramatically increased SNU398 cells sensitivity to MMC and Cisplatin-induced cell death (Figure 6A). Likewise, depletion of SPTBN1 by shRNA in HepG2 cells led to increased sensitivity to MMC, Cisplatin or IR (Figure 6B). Similar results were observed in Hep3B, SNU475 or SNU398 cells (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Somatic mutation D1089Y leads to loss of SPTBN1 tumor suppressor function. (A) Overexpression of wt SPTBN1, but not mutant SPTBN1-D1089Y, in SNU398 cells conferred resistance to MMC (left panel) or to Cisplatin (middle panel). Anti-HA antibody was used for the Western blot to check the expression of infected SPTBN1 (right panel). (B) HepG2-shRNA-SPTBN1 cells with SPTBN1 knockdown are significantly more sensitive to MMC (left panel), Cisplatin (middle panel) or IR-induced toxicity (right panel) than HepG2-shRNA-Ctrl cells. (C) Hep3B (left panel), SNU475 (middle panel), or SNU398 (right panel) cells with SPTBN1 knockdown by shRNA are significantly more sensitive to MMC than shRNA-Ctrl cells, representatively. Data presented as “mean ± SD” in A-C were obtained from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (* P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (D) Impaired DNA damage response (DDR) in the absence of SPTBN1. Phospho-Chk2 foci (pChk2) were analyzed at different time points in primary MEF cells after exposure to 10 Gy IR. IR induced significantly more pChk2 foci in Sptbnl+/+ cells than Sptbn1+/+ cells. Data presented as “mean ± SD” from 3 independent experiments analyzed by student t-test (*P < 0.01). (E) Overexpression of wt SPTBN1, but not mutant SPTBN1-D1089Y, in SNU398 cells led to altered DDR and decreased p-Chk2 levels. Total Chk2 was used for density normalization. (F) Overexpression of wt SPTBN1but not SPTBN1-D1089Y mutant inhibits colony formation capability of SNU475 cells in soft-agar assay.

To determine if the observed hypersensitivity to DNA damage was a repercussion from defective DNA repair pathway, foci formation was performed using phospho-Chk2 as a marker of DNA damage response.35 We found that Sptbn1−/− MEFs treated with IR had higher residual phospho-Chk2 foci (Figure 6D), suggesting a critical role of SPTBN1in DNA damage repair that we have reported previously. Consistently, ectopic expression of SPTBN1-Mid-wt but not the mutant (SPTBN1-Mid-D1089Y) significantly decreased the expression levels of phospho-Chk2 in SNU398 cells (Figure 6E). Furthermore, SPTBN1-Mid-wt but not SPTBN1-Mid-D1089Y mutant inhibits colony formation capability of SNU475 cells in soft-agar assay (Figure 6F). The data demonstrate that the D1089Y mutant leads to loss of TGF-ß/SPTBN1 tumor suppressor function possibly through modulation of DNA damage response.34 Taken together, our results indicated that genes of the TGF-β superfamily, including SPTBN1, were suppressed both transcriptionally and by somatic mutations in a significant proportion of HCCs, highlighting the importance of these alterations as potential drivers of liver carcinogenesis.

Discussion

Our integrative analyses of a large number of open-access and the new HCC cases provide new insights into the critical role of the TGF-β pathway in HCC development. We found that TGF-β signaling is not only pivotal for regulation of hepatocyte proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition in the liver, as previously described, but also that it could be involved in maintenance of genomic stability in the context of genotoxic injury.34, 36, 37 Our studies extend beyond our previous study38 providing an in depth and comprehensive pathway specific, as well as functional analysis in the TCGA HCC cohort. We show that frequent aberrations of TGF-β signaling occur in HCCs at both the transcriptomic level and the genomic level. A recent study supports multiple aspects of our TCGA analyses, particularly the larger cluster of the ‘activated’ signature, where activated TGF-β signaling through Snail leads to tumor progression in HCC.27 This recent study also indicates TGF-β tumor suppression occurs in the context of p53 deficiency. However, these latter findings are not supported by other studies demonstrating that TGF-β and p53 pathways are independent of each other, warranting further investigation.39, 40

We found a strong correlation between DNA damage repair genes and aberrations in TGF-β superfamily at both the transcriptomic level and the genomic level in HCC. 38% of TCGA HCC samples had somatic mutations in TGF-β pathway that were associated with mutations in several of the DNA repair pathway genes, such as ATR, FANCD2, FANCM, FAN1, RAD51, and TP53BP1. TGF-β signaling has previously been proposed to function as an extracellular sensor of ionizing radiation-induced cell damage or injury.14, 41 Keratinocytes isolated from TGFβ1-null mice exhibit marked genomic instability that could accelerate tumor progression.41 Genomic alteration in TGFBR1, TGFBR2, ACVR2A, ACVR1B, SMAD2, SMAD3 and SMAD4 occur in 87% of the hypermutated colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability.42 This observation suggests that TGF-β signaling may directly affect DNA repair and genomic stability more prominently than previously considered. Our functional studies demonstrate that this SPTBN1 mutation results in HCC cells that are more sensitive to DNA crosslinking agents Mitomycin C and Cisplatin, suggesting that TGF-β/SPTBN1 may directly regulate DNA damage repair-associated genes, specifically those involved in double stranded DNA interstrand cross-link repair.

An emerging theme in cancer, stem cells and aging research is that chromatin silencers, influenced by the sirtuin genes, appear to regulate longevity as well as cancer across living systems from yeast to mammals.43 The mammalian sirtuin family consists of seven NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases that regulate a wide range of intracellular process.30, 31 The incidence of human malignancies increases exponentially as a function of aging, suggesting a mechanistic connection between aging (longevity) and carcinogenesis.44, 45 Mouse models with loss of function of sirtuin genes have been shown to contribute to a tumor permissive phenotype.44 SIRT2-deficient mice develop gender-specific tumorigenesis: females develop mammary tumors, and males predominantly develop HCC.46 Human breast cancers and HCC samples exhibit reduced SIRT2 levels compared with normal tissues. Also, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from SIRT3-deficient mice exhibit abnormal mitochondrial physiology as well as increases in stress-induced superoxide levels and genomic instability. SIRT3-deficient mice develop ER/PR-positive mammary tumors and older mice suffer from HCC.47 SIRT1 associates with SMAD3, deacetylates SMAD3 and increases TGF-β/SMAD3 target gene activation in cancer.48 The surprising observations that SIRT6 mouse mutants develop HCCs, and that alterations in SIRT6 and TGF-β members could portend a poor prognosis, provide new clues to HCCs, and lend further significance to integrating TCGA based genomics with mouse models.

Major risk factors for HCC include HBV and HCV infection, alcoholic liver disease, cigarette smoking, food contaminants, hemochromatosis, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. An interesting finding from the TCGA analyses has been that etiological sources do not specify any particular mutational or transcriptomic pattern/signature, such as telomerase specific mutations for HBV, and β-catenin for HCV. The pathogenesis of liver cancer is a multistep process that begins with the development of damage from hepatic inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis, a process that may favor the acquisition and accumulation of genetic alterations. The two TGF-β signatures that we identified here may facilitate our understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms of TGF-β signaling associated with HCC initiation and progression. Our studies show raised TGF-β levels in 35% of HCCs, and are further supported by the recent Phase 2 clinical trial targeting TGF-β, that resulted in a marked increase in overall survival of up to 21 months specifically in patients with high TGF-β and alpha-fetoprotein levels, compared to a current 9–11 months for advanced HCC.49 The clusters also provide a logical approach towards targeting HCC. For instance, targeting VEGF may prove to be efficacious only in the “activated” cluster, whereas targeting FGFs may prove to be important in the “inactivated” cluster. Future biomarker driven targeted therapeutic approaches to HCC, could also include the DNA repair pathway, and together could alter the course of this lethal cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Wilma S Jogunoori, and Young Jin Gi for technical support. This research was supported by NIH grants R01 AA023146 (L. Mishra), R01 CA106614 (L. Mishra), R01 CA042857 (L. Mishra), VA Merit I01BX003732 (L. Mishra), P01 CA130821 (L. Mishra). Multidisciplinary Research Program (MRP) Proposal (L. Mishra), Science & Technology Acquisition and Retention Funding (STARs) (L. Mishra), R01CA120895 (S. Li) and R01DK102767–01A1 (S. Li), CA143883 and CA083639 (NCI; MD Anderson TCGA Genome Data Analysis Center), and MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016672 (the Bioinformatics Shared Resource).

Grant support/Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R01AA023146 (L. Mishra), P01CA130821 (L. Mishra), VA Merit I01BX003732 (L. Mishra), R01CA120895 (S. Li) and R01DK102767–01A1 (S. Li).

Abbreviations:

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HDAC

Histone deacetylases

- LIHC

liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- OS

Overall Survival

- SIRT

Sirtuin

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TERT

Telomerase

- TGF-β

Transforming growth Factor-beta

- wt

wild type

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- COSMIC

Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- MDACC

MD Anderson Cancer

- GUSM

Georgetown University School of Medicine

- HR

Hazard Ratio

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None

Author contributions

LM planned and supervised the execution of the entire study. JC, J-SC, LP, XS, RA performed Transcriptome sequencing analysis in TCGA HCC database, and validate TGF-β signature in other independent HCC cohorts, JC and J-SC, performed somatic mutation D1089Y functional analyses, DNA damage and cell viability assays and soft-agar colony formation assays. NP, RM and AH performed molecular modeling studies of SPTBN1 (D1089Y), SZ, SR and C-XD performed sirtuin family expression analyses. PF and FZ provided 8 human HCC and samples that were analyzed in MD Anderson Cancer Center. KS, JW, BM, XW, AR, NP, RM, AH, R-CW, DW, SL, RA, CX, C-XD provided intellectual input and edited manuscript. LM designed and coordinated the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.White DL, Thrift AP, Kanwal F, et al. Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in All 50 United States, From 2000 Through 2012. Gastroenterology 2017;152:812–820 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GLOBOCAN 2012: Liver cancer: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. International Agency for Research on Cancer: World Health Organization. 2017. (Accessed on Jun 11, 2017 at http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/FactSheets/cancers/liver-new.asp).

- 3.Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-Based Diagnosis, Staging, and Treatment of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2016;150:835–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majumdar A, Curley SA, Wu X, et al. Hepatic stem cells and transforming growth factor beta in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;9:530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Totoki Y, Tatsuno K, Covington KR, et al. Trans-ancestry mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma genomes. Nat Genet 2014;46:1267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guichard C, Amaddeo G, Imbeaud S, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet 2012;44:694–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2008;68:6779–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singal AG, El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular Carcinoma From Epidemiology to Prevention: Translating Knowledge into Practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:2140–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colak S, Dijke PT. Targeting TGF-β Signaling in Cancer. Trends in Cancer 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz LH, Likhter M, Jogunoori W, et al. TGF-beta signaling in liver and gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Lett 2016;379:166–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David CJ, Huang YH, Chen M, et al. TGF-beta Tumor Suppression through a Lethal EMT. Cell 2016;164:1015–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muraoka-Cook RS, Kurokawa H, Koh Y, et al. Conditional overexpression of active transforming growth factor beta1 in vivo accelerates metastases of transgenic mammary tumors. Cancer Res 2004;64:9002–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma V, Antonacopoulou AG, Tanaka S, et al. Enhancement of TGF-beta signaling responses by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Arkadia provides tumor suppression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 2011;71:6438–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Yao ZX, Chen JS, et al. TGF-beta/beta2-spectrin/CTCF-regulated tumor suppression in human stem cell disorder Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. J Clin Invest 2016;126:527–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katuri V, Tang Y, Li C, et al. Critical interactions between TGF-beta signaling/ELF, and E-cadherin/beta-catenin mediated tumor suppression. Oncogene 2006;25:1871–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitisin K, Ganesan N, Tang Y, et al. Disruption of transforming growth factor-beta signaling through beta-spectrin ELF leads to hepatocellular cancer through cyclin D1 activation. Oncogene 2007;26:7103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang Y, Kitisin K, Jogunoori W, et al. Progenitor/stem cells give rise to liver cancer due to aberrant TGF-beta and IL-6 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:2445–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weksberg R, Shuman C, Beckwith JB. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao ZX, Jogunoori W, Choufani S, et al. Epigenetic silencing of beta-spectrin, a TGF-beta signaling/scaffolding protein in a human cancer stem cell disorder: Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. J Biol Chem 2010;285:36112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadzic N, Finegold MJ. Liver neoplasia in children. Clin Liver Dis 2011;15:443–62, vii-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2006;7:21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah SP, Roth A, Goya R, et al. The clonal and mutational evolution spectrum of primary triple-negative breast cancers. Nature 2012;486:395–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Kobayashi S, Qiao W, et al. Induction of intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma by liver-specific disruption of Smad4 and Pten in mice. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang YA, Zhang GM, Feigenbaum L, et al. Smad3 reduces susceptibility to hepatocarcinoma by sensitizing hepatocytes to apoptosis through downregulation of Bcl-2. Cancer Cell 2006;9:445–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roessler S, Long EL, Budhu A, et al. Integrative genomic identification of genes on 8p associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression and patient survival. Gastroenterology 2012;142:957–966 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mas VR, Maluf DG, Archer KJ, et al. Genes involved in viral carcinogenesis and tumor initiation in hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Med 2009;15:85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moon H, Ju HL, Chung SI, et al. Transforming Growth Factor Beta Promotes Liver Tumorigenesis in Mice via Upregulation of Snail. Gastroenterology 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaramillo MC, Zhang DD. The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev 2013;27:2179–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Copple IM, Goldring CE, Jenkins RE, et al. The hepatotoxic metabolite of acetaminophen directly activates the Keap1-Nrf2 cell defense system. Hepatology 2008;48:1292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HS, Xiao C, Wang RH, et al. Hepatic-specific disruption of SIRT6 in mice results in fatty liver formation due to enhanced glycolysis and triglyceride synthesis. Cell Metab 2010;12:224–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao C, Wang RH, Lahusen TJ, et al. Progression of chronic liver inflammation and fibrosis driven by activation of c-JUN signaling in Sirt6 mutant mice. J Biol Chem 2012;287:41903–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meier D, Schindler D. Fanconi anemia core complex gene promoters harbor conserved transcription regulatory elements. PLoS One 2011;6:e22911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korc M Smad4: gatekeeper gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest 2009;119:3208–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Shukla V, Farci P, et al. Loss of the transforming growth factor-beta effector beta2-Spectrin promotes genomic instability. Hepatology 2017;65:678–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell 2003;3:421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michalopoulos GK. Hepatostat: Liver regeneration and normal liver tissue maintenance. Hepatology 2017;65:1384–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Im YH, Kim HT, Kim IY, et al. Heterozygous mice for the transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor gene have increased susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2001;61:6665–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address wbe, Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive and Integrative Genomic Characterization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell 2017;169:1327–1341 e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris SM, Baek JY, Koszarek A, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling promotes hepatocarcinogenesis induced by p53 loss. Hepatology 2012;55:121–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Q, Zou Y, Nowotschin S, et al. The p53 Family Coordinates Wnt and Nodal Inputs in Mesendodermal Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2017;20:70–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glick A, Popescu N, Alexander V, et al. Defects in transforming growth factor-beta signaling cooperate with a Ras oncogene to cause rapid aneuploidy and malignant transformation of mouse keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:14949–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cancer Genome Atlas N Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012;487:330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Igarashi M, Guarente L. mTORC1 and SIRT1 Cooperate to Foster Expansion of Gut Adult Stem Cells during Calorie Restriction. Cell 2016;166:436–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finkel T, Deng CX, Mostoslavsky R. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature 2009;460:587–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015;347:78–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HS, Vassilopoulos A, Wang RH, et al. SIRT2 maintains genome integrity and suppresses tumorigenesis through regulating APC/C activity. Cancer Cell 2011;20:487–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim HS, Patel K, Muldoon-Jacobs K, et al. SIRT3 is a mitochondria-localized tumor suppressor required for maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and metabolism during stress. Cancer Cell 2010;17:41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang XZ, Wen D, Zhang M, et al. Sirt1 activation ameliorates renal fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF-beta/Smad3 pathway. J Cell Biochem 2014;115:996–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giannelli G, Villa E, Lahn M. Transforming growth factor-beta as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2014;74:1890–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.