Introduction

The current document summarizes the state-of-the-art knowledge as it relates to management of male lower urinary tract symptoms (MLUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) by updating the 2010 Canadian Urological Association (CUA) BPH guideline.1 The process continues to highlight the essential diagnostic and therapeutic information in a Canadian context. The information included in this document includes that reviewed for the 2010 guideline and further information obtained from an updated MEDLINE search of the English language literature, as well as review of the most recent American Urological Association (AUA)2 and European Urological Association (EAU) guidelines.3 References include those of historical importance, but management recommendations are based on literature published between 2000 and 2017. When information and data is available from multiple sources, the most relevant (usually most recent) article (committee opinion) is cited.

These guidelines are directed toward the typical male patient over 50 years of age, presenting with LUTS and an enlarged benign prostate (BPE) and/or benign prostatic obstruction (BPO). It is recognized that men with LUTS associated with non-BPO causes may require more extensive diagnostic workup and different treatment considerations.

In this document, we will address both diagnostic and treatment issues. Diagnostic guidelines are described in the following terms as: mandatory, recommended, optional, or not recommended. The recommendations for diagnostic guidelines and principles of treatment were developed on the basis of clinical principle (widely agreed upon by Canadian urologists) and/or expert opinion (consensus of committee and reviewers). The grade of recommendation will not be offered for diagnostic recommendations. Guidelines for treatment are described using the GRADE approach4 for summarizing the evidence and making recommendations

1. Diagnostic guidelines

The committee recommended minor revisions in regard to diagnostic considerations as outlined in the 2010 CUA BPH guideline.1

1.1. Mandatory

In the initial evaluation of a man presenting with LUTS, the evaluation of symptom severity and bother is essential. Medical history should include relevant prior and current illnesses, as well as prior surgery and trauma. Current medication, including over-the-counter drugs and phytotherapeutic agents, must be reviewed. A focused physical examination, including a digital rectal exam (DRE), is also mandatory. Urinalysis is required to rule out diagnoses other than BPH that may cause LUTS and may require additional diagnostic tests.1–3,5,6,7

– History

– Physical examination including DRE

– Urinalysis

1.2. Recommended

Symptom inventory (should include bother assessment): A formal symptom inventory (e.g., International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS] or AUA Symptom Index [AUA-SI]) is recommended for an objective assessment of symptoms at initial contact, for followup of symptom evolution for those on watchful waiting, and for evaluation of response to treatment.8–11

PSA: Testing of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) should be offered to patients who have at least a 10-year life expectancy and for whom knowledge of the presence of prostate cancer would change management, as well as those for whom PSA measurement may change the management of their voiding symptoms (estimate for prostate volume). Among patients without prostate cancer, serum PSA may also be a useful surrogate marker of prostate size and may also predict risk of BPH progression.12,13

1.3. Optional

In cases where the physician feels it is indicated or diagnostic uncertainty exists, it is reasonable to proceed with one or more of the following:

– Serum creatinine

– Urine cytology

– Uroflowmetry

– Post-void residual

– Voiding diary (recommend frequency volume chart for men with suspected nocturnal polyuria)

– Sexual function questionnaire

1.4. Not recommended

The following diagnostic modalities are not recommended in the routine initial evaluation of a typical patient with BPH-associated LUTS. These investigations may be required in patients with a definite indication, such as hematuria, uncertain diagnosis, DRE abnormalities, poor response to medical therapy, or for surgical planning.

– Cytology

– Cystoscopy

– Urodynamics

– Radiological evaluation of upper urinary tract

– Prostate ultrasound

– Prostate biopsy

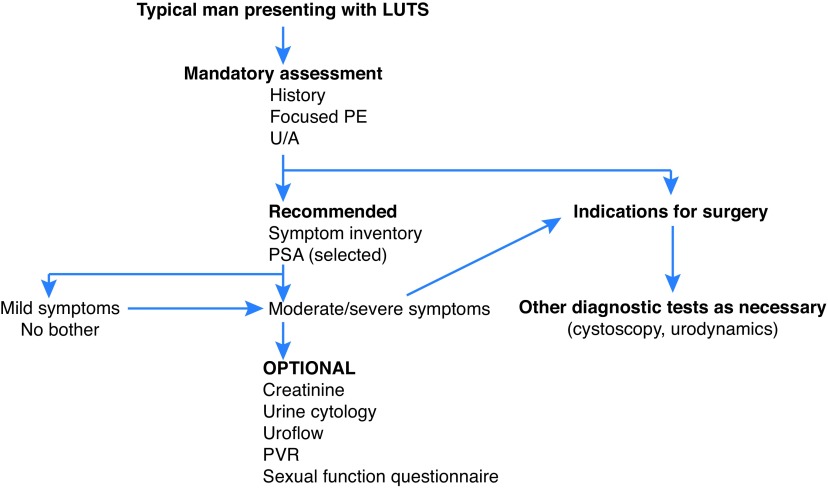

An algorithm summarizing the appropriate diagnostic steps in the workup of a typical patient with MLUTS/BPH is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm of appropriate diagnostic steps in the workup of a typical patient with male lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH). PE: physical exam; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; PVR: post-void residual; U/A: urinalysis.

1.5. Further diagnostic considerations for surgery

Indications for surgery: Indications for MLUTS/BPH surgery1–3 include a) recurrent or refractory urinary retention; b) recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs); c) bladder stones; d) recurrent hematuria; e) renal dysfunction secondary to BPH; f) symptom deterioration despite medical therapy; and g) patient preference. The presence of a bladder diverticulum is not an absolute indication for surgery unless associated with recurrent UTI or progressive bladder dysfunction.

Preoperative testing: Determination of prostate size and extent of median lobe are related to procedure-specific indications (see section on Surgical Treatment). Cystoscopy should be performed to evaluate prostate size, as well as presence or absence of significant middle/median lobe. Ultrasound (US) (either by transrectal ultrasound [TRUS] or transabdominal US) is recommended if further information in regard to size of prostate and extent of median lobe presence is required when choosing modality of surgical therapy.

2. Treatment guidelines

2.1. Principles of treatment

Therapeutic decision-making should be guided by the severity of the symptoms, the degree of bother, and patient preference. Information on the risks and benefits of BPH treatment options should be explained to all patients who are bothered enough to consider therapy. Patients should be invited to participate as much as possible in the treatment selection.

Patients with mild symptoms (e.g., IPSS <7) should be counselled about a combination of lifestyle modification and watchful waiting. Patients with mild symptoms and severe bother should undergo further assessment.

Treatment options for patients with bothersome moderate (e.g., IPSS 8–18) and severe (e.g., IPSS 19–35) symptoms of BPH include watchful waiting/lifestyle modification, as well as medical, minimally invasive, or surgical therapies.

Physicians should use baseline age, LUTS severity, prostate volume, and/or serum PSA to advise patients of their individual risk of symptom progression, acute urinary retention or future need for BPH-related surgery (these risk factors identify patients at risk for progression).

A variety of lifestyle changes may be suggested for patients with non-bothersome symptoms. These can include the following:

– Fluid restriction, particularly prior to bedtime

– Avoidance of caffeinated beverages, alcohol, and spicy foods

– Avoidance/monitoring of some drugs (e.g., diuretics, decongestants, antihistamines, antidepressants)

– Timed or organized voiding (bladder retraining)

– Pelvic floor exercises

– Avoidance or treatment of constipation

2.2. Post-treatment followup

Watchful waiting: Patients on watchful waiting should have periodic physician-monitored visits.

Medical therapy: Patients started on medical therapy should have followup visit(s) to assess for efficacy and safety (side effects of medications). If the patient-directed therapeutic goal is achieved, the patient may be followed by the primary care physician as part of a shared-care approach. The primary care physician should be counselled with clear instructions on followup and re-referral as necessary.

Surgical therapy: Patients after prostate surgery should be reviewed 4–6 weeks after catheter removal to evaluate treatment response (with symptom assessment [e.g., IPSS], and if indicated, uroflowmetry, and post-void residual [PVR] volume) and adverse events. The individual patient’s circumstances and type of surgical procedure employed will determine the need for and/or type of further followup required by the urologist and/or primary care physician.

2.3. Medical therapy

The committee recommended few change in the recommendations for the primary medical management of BPH and MLUTS with alpha-blockers and/or 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5ARIs) since 2010. Since the 2010 guideline publication, new evidence is available in regard to other medical therapy, including combination therapy, for the treatment of MLUTS.

2.3.1. Alpha-blockers

Alfuzosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin, terazosin, and silodosin are appropriate treatment options for LUTS secondary to BPH.12–20,22,23 Doxazosin and terazosin require dose titration and blood pressure monitoring. Alpha-blockers do not alter the natural progression of the disease (little impact on prostate growth, the risk of urinary retention or the need for BPH-related surgery). The most common adverse effect associated with alpha-blockers is dizziness (2–10%, with the highest rates for terazosin and doxazosin), while ejaculatory disturbances are most often reported with tamsulosin and silodosin. Floppy iris syndrome has been reported in patients on alpha-blockers, particularly tamsulosin, but this does not appear to be an issue in men with no planned cataract surgery and can be managed by the ophthalmologist, who is aware that the patient is on the medication.21 Although there are differences in the adverse event profiles of these agents, all five agents appear to have equal clinical effectiveness. The choice of agent should depend on the patient’s comorbidities, side effect profiles, and tolerance.

We recommend alpha-blockers as an excellent first-line therapeutic option for men with symptomatic bother who desire treatment (strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence).

2.3.2. 5ARIs

Several studies have demonstrated that 5ARI therapy, in addition to improving symptoms and causing a modest (25–30%) shrinkage of the prostate, can alter the natural history of BPH through a reduction in the risk of acute urinary retention (AUR) and the need for surgical intervention.24,25 Efficacy is noted in patients with a prostate volume >30 cc (and/or PSA levels >1.5 ng/ml). 5ARI treatment is associated with erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, ejaculation disorders, and rarely, gynecomastia.

We recommend 5ARIs (dutasteride and finasteride) as appropriate and effective treatment for patients with LUTS associated with demonstrable prostatic enlargement (strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence).

2.3.3. Combination therapy (alpha-blocker and 5ARI)

Prognostic factors suggesting the potential for BPH progression risk26,27 include: serum PSA >1.4 ng/mL, age >50 years, and gland volume >30 cc. Clinical trial results have shown that combination therapy significantly improves symptom score and peak urinary flow compared with either of the monotherapy options. Combination medical therapy is associated with decreased risk of urinary retention and/or prostate surgery, but also the additive side effects of dual therapy (in particular ejaculatory disturbances).28,29

We recommend that the combination of an alpha-adrenergic receptor blocker and a 5ARI as an appropriate and effective treatment strategy for patients with symptomatic LUTS associated with prostatic enlargement (> 30 or 35 cc) (strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence).

It may be appropriate to consider discontinuing the alpha blockers in patients successfully managed with combination therapy after 6–9 months of therapy.30,31

We suggest that patients successfully treated with combination therapy may be given the option of discontinuing the alpha-blocker. If symptoms recur, the alpha-blocker should be restarted (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

2.3.4. Antimuscarinic and beta-3 agonist medications

Storage symptoms (urgency, frequency, nocturia) are a bothersome component of MLUTS associated with BPH. Antimuscarinics (anticholinergics) and the beta-3 agonist have demonstrated improvements in male storage LUTS (with and without BPH), including reductions in frequency, urgency, and urgency incontinence episodes.32,33 Studies of contemporary antimuscarinics, such as tolterodine and fesoterodine and the beta-3 agonist, mirabegron have shown low rates of urinary retention, although caution may be used in elderly men and those with significant bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) (with PVR >250–300 cc since there is little evidence of safety in men with high PVRs).

We suggest that antimuscarinics or beta-3 agonists may be useful therapies in MLUTS/BPH with caution in those with significant BOO and/or PVR (conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence).

Evidence shows that alpha-blocker combination with antimuscarinics can benefit some men with both voiding and storage symptoms, while antimuscarinic and beta-3 agonist combination therapies can be beneficial in some men with significant storage symptoms.34,35

We suggest that that alpha-blocker combination with antimuscarinics or beta-3 agonists may be useful therapies in MLUTS/BPH in some men (failure of alpha blocker monotherapy) with both voiding and storage symptoms (conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence).

2.3.5. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5Is) have been shown to not only improve erectile function, but also are an effective treatment for male LUTS. Tadalafil 5 mg daily, due to its longer half-life, is approved for male LUTS. Studies have shown improvements in IPSS, storage and voiding symptoms, and quality of life.36

We recommend long-acting PDE5Is as therapy for men with MLUTS/BPH, particularly men with both MLUTS and erectile dysfunction (strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence).

2.3.6. Desmopressin

Nocturnal polyuria often coexists with MLUTS and BPH, but may not respond to typical BPH pharmacotherapies. Desmopressin is a synthetic analogue of the antidiuretic hormone, arginine vasopressin (AVP). Desmopressin reduces total nocturnal voids and increases hours of undisturbed sleep by reducing urine production in men with nocturnal polyuria.37 While the risk of hyponatremia is low in men with normal baseline serum sodium, sodium must be checked at baseline in all men, and 4–8 days as well as 30 days after initiation of treatment in men taking desmopressin melts or men ≥65 years taking 50 μg oral disintegrating tablet.

We recommend desmopressin as a therapeutic option in men with MLUTS/BPH with nocturia as result of nocturnal polyuria (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

2.3.7. Phytotherapies

Plant-based herbal preparations may appeal to some patients. Common formulations include Serenoa repens (saw palmetto), Pygeum africanum (African plum bark), and Urtica dioica (stinging nettle). Phytotherapies lack consistent formulation, predictable pharmacokinetics, and regulatory oversight. Numerous studies and Cochrane meta-analyses report no significant difference between phytotherapies and placebo, as measured by AUA-SI, peak flow rates, prostate volume, residual urine volume, PSA, or quality of life.38–41 There are few side effects associated with phytotherapies.

We do not recommend phytotherapies as standard treatment for MLUTS/BPH (moderate recommendation based on high-quality evidence).

2.4. Surgical therapy

2.4.1. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

Monopolar TURP (M-TURP): M-TURP remains the primary, standard-reference surgical treatment option for moderate to severe LUTS due to BPH in patients with prostate volume 30–80 cc.42 Perioperative mortality has decreased over time (0.1%), while morbidity is related to prostate volume (particularly >60 cc).43 Contemporary series have reported the following complications: bleeding (2–9%), capsule perforation with significant extravasation (2%), TUR syndrome (0.8%), urinary retention (4.5–13%), infection (3–4%; sepsis 1.5%), incontinence (<1%), bladder neck contracture (3–5%), retrograde ejaculation (65%), erectile dysfunction (6.5%), and surgical retreatment (2%/year).44,45

We recommend M-TURP as a standard first-line surgical therapy for men with moderate to severe MLUTS/BPH with prostate volume of 30–80 cc (strong recommendation based on high-to moderate-quality evidence).

Bipolar TURP (B-TURP): B-TURP offers a resection alternative to M-TURP in men with moderate to-severe LUTS secondary to BPH with similar efficacy, but lower perioperative morbidity.45 The choice of B-TURP should be based on equipment availability, surgeon experience, and patient preference.

We recommend B-TURP as a standard first-line surgical therapy for men with moderate to severe MLUTS/BPS with prostate volume of 30–80 cc (strong recommendation based on moderate-to high-quality evidence).

Bipolar plasma kinetic vaporization (BPKVP): Also known as the “plasma button” procedure, BPKVP is an alternative to TURP. This procedure uses a mushroom-shaped axipolar electrode to apply low-temperature radiofrequency plasma energy to vaporize prostate tissue on contact. Comparable IPSS, peak flow rate (Qmax), PSA reduction, as well as reduced operative time, catheterization time, and hospital stay were observed with BPKVP compared to M-TURP in men with prostate volume <60 cc.46,47 Long-term efficacy of BPKVP, especially for prostate volume >60 cc, is still required.

We suggest BPKVP as an alternative first-line surgical therapy for men with moderate to severe MLUTS/BPH and prostate volume <60 cc (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

2.4.2. Open simple prostatectomy (OSP)

OSP is an appropriate and effective treatment alternative for men with moderate to severe LUTS with substantially enlarged prostates >80–100 cc and who are significantly bothered by symptoms.48 Other indications for OSP include plans for concurrent bladder procedure, such as diverticulectomy or cystolithotomy, and in men who are unable to be placed in dorsal lithotomy position due to severe hip disease.49 OSP is the most invasive surgical method requiring longer hospitalization and catheterization. The estimated transfusion rate has been reported from 7–14%.48,49 Long-term complications include transient urinary incontinence (8–10%), bladder neck contracture, and urethral stricture (5–6%).48,49 Less invasive techniques, including laparoscopic and robotic approaches have demonstrated equivalent efficacy and potentially fewer complications compared to OSP, but require specialized equipment and relevant skills.50

We recommend OSP as a first-line surgical therapy for men with moderate to severe MLUTS/BPS and enlarged prostate volume >80 cc (strong recommendation based on moderate-to high-quality evidence).

2.4.3. Laser prostatectomy

Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP): HoLEP provides significant and durable improvements in Qmax, PVR volume, quality of life, IPSS, and PSA reduction51,52 and can be used to treat men on anticoagulation and those with bleeding dyscrasia. There is a low reoperation rate (approximately 4% for recurrent LUTS) within series with long followup (up to 7–8 years).52,53 The procedure requires a steep learning curve (estimated >20–50 cases)53 often requiring fellowship training.

We recommend HoLEP as an alternative to TURP or OSP in men with moderate to severe LUTS if performed by a HoLEP-trained surgeon (strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence).

Photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP): Greenlight-PVP (180W XPS and 120W HPS systems) provides comparable outcomes to TURP in terms of durable improvements in IPSS and Qmax with similar overall complication rate.54 Five-year mid-term durability of XPS reported a 1.6% retreatment rate.55 PVP has been shown to be a cost-effective alternative to TURP in the Canadian setting. The data suggests superior safety in men on anticoagulation and/or high cardiovascular risk.55

We recommend PVP as an alternative to TURP in men with moderate to severe LUTS (strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence). We suggest Greenlight PVP therapy as an alternate surgical approach in men on anticoagulation or with a high cardiovascular risk (conditional recommendation based on moderate quality evidence).

Diode laser vaporization of the prostate: Diode laser vaporization (and enucleation) of the prostate provides improved IPPS, Qmax, and PVR compared to baseline.56,57 While providing strong hemostatic properties, high rates of dysuria, high-reoperation rates (8–33%), and persisting stress urinary incontinence (9.1%) have been reported.

We suggest diode laser vaporization of the prostate as an alternative to TURP in men with moderate to severe LUTS (conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence). We suggest diode laser vaporization of the prostate as an alternate surgical approach in men on anticoagulation (conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence).

Thulium laser: Tm:YAG vaporization (also enucleation and vapoenucleation) has comparable efficacy and safety outcomes to TURP, PVP, and HoLEP for a wide range of prostate gland sizes and in patients taking oral anticoagulants with lower complication and bleeding rates compared to TURP and open simple prostatectomy.58,59

We suggest Tm:YAG vaporization of the prostate as an alternative to TURP in men with moderate to severe LUTS with prostate volume <60 cc. Thulium enucleation may be an alternative to OSP and HoLEP in men with moderate to severe LUTS with prostate volume >80 cc (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

2.4.4. Transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP)

TUIP is an appropriate therapy for men with a small prostate size <30 cc without a middle lobe.60 Symptoms and voiding parameters are improved, the risk of retrograde ejaculation and TUR syndrome is reduced (18.2% and 0%) compared to TURP, however, the risk of surgical retreatment for LUTS related to BPH are significantly higher for TUIP (18.4%) than after TURP (7.2%).

We recommend TUIP to treat moderate to severe LUTS in men with prostate volume <30 cc without a middle lobe (strong recommendation based on moderate-to high-quality evidence).

2.4.5. Minimally invasive techniques

Transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT): TUMT is a true outpatient procedure and an option for elderly patients with significant comorbidities or greater anaesthesia risks.61,62 Although short-term success for LUTS improvement have been reported, the long-term durability of TUMT is limited with five-year cumulative retreatment rates between 42 and 59%.63

We suggest TUMT therapy as a consideration for treatment of carefully selected, well-informed men (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA): The TUNA device results in short-term voiding symptoms and urinary flow parameter improvement,64 but it does not reach the same level of efficacy and long-lasting success as TURP. Scarce data and lack of replication of comparisons hinder the assessment of TUNA to other minimally invasive surgical procedures. Long-term treatment durability also appears poor, with overall retreatment rate of 19% at two years.65 To the best of our knowledge, TUNA is no longer offered by any Canadian urology centre. This may change if new devices and/or trial data become available.

We suggest TUNA therapy not be offered as a consideration for treatment of BPH/LUTS (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

Prostatic stents: Temporary stents can provide short-term relief from BPO in patients temporarily unfit for surgery.66 In general, stents are subject to misplacement, migration, and poor tolerability because of exacerbation of LUTS and encrustation. Given these common side effects, prostatic stents have a limited role in the treatment of moderate to severe LUTS.

We suggest prostatic stents only as an alternative to catheterization in men unfit for surgery with a functional detrusor (conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence).

2.4.6. New and emerging therapies

Prostatic urethral lift: The prostatic urethral lift procedure or Urolift® (small, permanent, suture-based nitinol tabbed implants compress encroaching lateral lobes delivered under cystoscopic guidance) provides less effective, but adequate and durable improvements in IPSS and QMax compared to TURP while preserving sexual function (no reported retrograde ejaculation observed at 12 months).67 Most complications are mild and resolve within four weeks. Surgical retreatment was 13.6% over five years.68

We suggest that prostatic urethral lift (Urolift) may be considered an alternative treatment for men with LUTS interested in preserving ejaculatory function, with prostates <80 cc and no middle lobe (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

Convective water vapour energy ablation: Ablation using the Rezum® system (uses the thermodynamic principle of convective energy transfer), report significant improvement of IPSS and Qmax at three months and sustained until 12 months69 with preservation of erectile and ejaculatory function.70 Reported two-year results have confirmed durability of the positive clinical outcome.71

We suggest that Rezum system of convective water vapour energy ablation may be considered an alternative treatment for men with LUTS interested in preserving ejaculatory function, with prostates <80 cc, including those with median lobe (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

Image-guided robotic waterjet ablation: Aquablation (robotic-guided hydrodissection ablates prostatic parenchyma while sparing collagenous structures such as blood vessels and the surgical capsule)72 has shown comparable improvements in efficacy and safety compared to TURP in men with <80 cc prostates (approximately 50% of patients having middle lobes) with significant decrease in risk of anejaculation.73

We suggest that aquablation be offered to men with LUTS interested in preserving ejaculatory function, with prostates <80 cc, with or without middle lobe. (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

Temporary implantable nitinol device (iTIND): iTIND is an emerging, temporary (five days and then removed under local anaesthetic), mechanical, stent-like device designed to remodel the bladder neck and the prostatic urethra through pressure necrosis. Early clinical experience demonstrated that implantation of iTIND is a feasible and safe procedure to perform and appears to provide measureable clinical benefit.74

We recommend that iTIND should not be offered at this time for the treatment of LUTS due to BPH (conditional recommendation based on very low-quality evidence).

Prostatic artery embolization (PAE): PAE, exclusively performed by interventional radiologists at specialized centres, results in significant IPSS, Qmax, and PVR improvement compared to baseline at 12 months,75 however, inferior outcomes compared to TURP 76–78 or OSP.79 Non-targeted embolization may lead to ischemic complications like transient ischemic proctitis, bladder ischemia, urethral and ureteral stricture, or seminal vesicles ischemia.

We recommend that PAE should not be offered at this time for the treatment of LUTS due to BPH (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

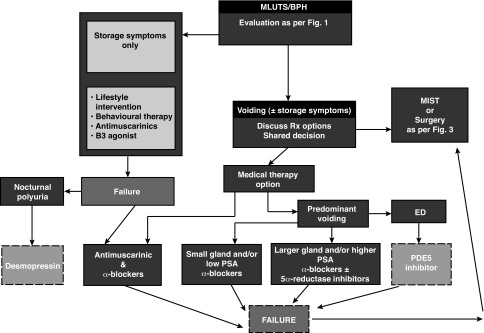

Algorithms summarizing the management of a patient with MLUTS/BPH are summarized in Figs. 2, 3.

Fig. 2.

Male lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia (MLUTS/BPH) management algorithm. ED: erectile dysfunction; PDE5: phosphodiesterase type 5; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

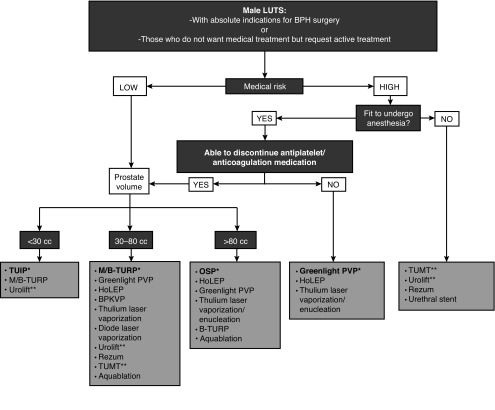

Fig. 3.

Treatment algorithm of bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) refractory to conservative/medical treatment or in cases of absolute operation indications. The flowchart was stratified by the patient’s ability to have anesthesia, cardiovascular risk, and prostate volume. *Current standard/first choice. The alternative treatments are presented in alphabetical order. **Must exclude the presence of a middle lobe. BPH: benign prostatic hyperplasia; B-TURP: bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate; HoLEP: holmium laser enucleation of the prostate; M/TURP: monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate; PVP: photoselective vaporization of the prostate; TUIP: transurethral incision of the prostate; TUMT: transurethral microwave therapy.

2.5. Special situations

2.5.1. Symptomatic prostatic enlargement without bothersome symptoms

Studies have shown that 5ARIs prevent progression of MLUTS/BPH in symptomatic men over the long-term.28,29

We suggest that selected, well-informed patients with symptomatic prostatic enlargement in the absence of significant bother may be offered a 5ARI to prevent progression of the disease (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

AUR: Data suggest that in patients with AUR, the use alpha-blockers (specifically tamsulosin, alfuzosin, and silodosin) during the period of catheterization will increase the chances of successful voiding after catheter removal,80,81 while the addition of a 5ARI may decrease the risk of future prostate surgery.28,29,82

We suggest that men with AUR secondary to BPH may be offered alpha-blocker therapy during the period of catheterization (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence).

Detrusor underactivity (DU): There is no effective treatment for DU, defined as a contraction of reduced strength and/or duration, resulting in prolonged bladder emptying and/or a failure to achieve complete bladder emptying within a normal time span.83 In primary DU, treatment approach should be to facilitate bladder emptying, identify agents that can decrease bladder contractility, or increase urethral resistance. Behavioural modification, including scheduled voiding and or double voiding, clean intermittent self-catheterization (CIC), or indwelling catheters, are optional strategies.84 The data suggests that DU is not necessarily a contraindication for TURP.85

We have no evidence-based specific recommendation for management of detrusor under-activity.

BPH-related bleeding: A complete assessment, including history and physical examination, urinalysis (routine microscopy, culture and sensitivity, cytology), upper tract radiological assessment and cystoscopy, is necessary to exclude other sources of bleeding. Finasteride has been reported to reduce the risk of recurrent BPH-related hematuria.86

We suggest that a trial with a 5ARI is appropriate in men with BPH-related hematuria (conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence).

BPH patients with prostate cancer concern: The BPH patient with an elevated serum PSA and negative prostate biopsy may be counselled on the potential benefits of 5ARI therapy (finasteride, dutasteride) for prostate cancer detection risk reduction.87,88 The patient must be aware of the possible low absolute increased risk (0.5–0.7%) in incidence of high-grade (Gleason 8–10) cancer with 5ARI use. Most experts believe this phenomenon was observed due to an artifact of prostate glandular cytoreduction, induced by the 5ARI, and it appears there is no demonstrable increase in prostate cancer mortality.89 Patients on 5ARI therapy who experience a rising PSA 6–12 months after PSA nadir is reached should be assessed for the possibility of high-grade prostate cancer.90

We recommend case-to-case patient-specific informed discussion and close PSA followup, as indicated in men on 5ARI therapy treatment for BPH (moderate recommendation based on high-quality evidence).

Summary

MLUTS secondary to BPH remains one of the most common age-related disorders afflicting men. As the aging of the Canadian population continues, more men will be seeking advice and looking for guidance from their healthcare providers on the management of their symptoms. The information offered in this guideline document, based on consensus evaluation of the best available evidence, will aid Canadian urologists as they strive to provide state-of-the-art care to their patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Nickel has been a consultant for Astellas, Auxillium, Eli Lilly, Farr Labs, Ferring, GSK, Pfizer, Redleaf Pharma, Taris Biomedical, Tribute, and Trillium Therapeutics; a lecturer for Astellas and Eli Lilly; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Eli Lilly, GSK, J&J, Pfizer, and Taris Biomedical. Dr. Aaron has attended advisory boards for AbbVie and Janssen; has been a speaker for Ferring and Janssen; holds investments in Johnson & Johnson; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Asetllas, Ferring, and Janssen. Dr. Elterman has attended advisory boards for, is a speaker for, and has received grant funding from Allergan, Astellas, Boston Scientific, Ferring, Medtronic, and Pfizer; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas and Medtronic. Dr. Zorn has received honoraria from Boston Scientific and as a proctor/lecturer for Greenlight; and participated in the WATER2 clinical trial with aquablation supported by Procept Biorobotics. The remaining authors report no competing personal or financial interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Nickel JC, Mendez-Probst CE, Whelan TF, et al. 2010 update: Guidelines for the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:308–14. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL, et al. American Urological Association guideline: Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) [Accessed Aug. 28, 2018]. Published 2010; reviewed and validity confirmed 2014. Available at http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia-(2010-reviewed-and-validity-confirmed-2014)

- 3.Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, et al. EAU guidelines on the assessment of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1099–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GRADE Guidelines 15. [Accessed Aug. 28, 2018]. Available at http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/

- 5.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, et al. Incontinence. 6th International Consultation on Incontinence; Tokyo. September 2016; ICUD; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nickel JC, Saad J. The American Urological Association 2003 guidelines on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A Canadian opinion. Can J Urol. 2004;11:2186–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsey EW, Elhilali M, Goldenberg GS, et al. Practice patterns of Canadian urologists in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;163:499–502. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockett ATK, Aso Y, Denis L, et al. Recommendations of the International Consensus Committee concerning: 1. Prostate symptom score (I-PSS) and quality of life assessment, 2. Diagnostic workup of patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of prostatism, 3. Patients evaluation for research studies, and 4. BPH treatment. In: Cockett ATK, Aso Y, Chatelain C, et al., editors. Proceedings of the first International Consultation on Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Paris: Scientific Communication; 1991. pp. 279–340. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–57. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson C, Link CL, Onel E, et al. The impact of lower urinary tract symptoms and comorbidities on quality of life: The BACH and UREPIK studies. BJU Int. 2007;99:347–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Leary MP, Wei JT, Roehrborn CG, et al. BPH registry and patient survey steering committee. Correlation of the international prostate symptom score bother question with the benign prostatic hyperplasia impact index in a clinical practice setting. BJU Int. 2008;101:1531–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitt JM, Slawin KM. PSA and PSA derivatives as predictors of BPH progression. Curr Urol Rep. 2007;8:269–74. doi: 10.1007/s11934-007-0072-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rendon RA, Mason RJ, Marzouk K, et al. Canadian Urological Association recommendations on prostate screening and early diagnosis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11:298–309. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukacs B, Grange JC, Comet D. One-year followup of 2829 patients with moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms treated with alfuzosin in general practice according to IPSS and a health-related quality-of-life questionnaire. BPM Group in General Practice. Urology. 2000;55:540–6. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00539-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsukamoto T, Masumori N, Rahman M, et al. Change in international prostate symptom score, prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia followed longitudinally. Int J Urol. 2007;14:321–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapple CR. Alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonist in the year 2000: Is there anything new? Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:9–16. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marberger M, Harkawa R, de la Rosette J. Optimizing the medical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2004;45:411–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozlu M, Ulusoy E, Cayan S, et al. A comparison of four different alpha 1-blockers in benign prostatic hyperplasia patients with and without diabetes. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38:391–5. doi: 10.1080/00365590410015678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirby RS. A randomized, double-blind crossover study of tamsulosin and controlled-release doxazosin in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2003;91:41–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.03077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Reijke TM, Klarskov P. Comparative efficacy of two alpha adrenoreceptor antagonists, doxazosin and alfuzosin, in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms from benign prostatic enlargement. BJU Int. 2004;93:757–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takmaz T, Can I. Clinical features, complications, and incidence of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome in patients taking tamsulosin. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17:909–13. doi: 10.1177/112067210701700607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchison A, Farmer R, Verhamme K, et al. The efficacy of drugs for the treatment of LUTS/BPH, a study in 6 European countries. Eur Urol. 2007;51:207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilt TJ, Howe RW, Rutks IR, et al. Terazosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD003851. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. the PLESS Study Group. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:557–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802263380901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, Nickel JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2002;60:434–41. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JB, Roehrborn CG, Schalken JA, et al. The progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia: Examining the evidence and determining the risk. Eur Urol. 2001;39:390–9. doi: 10.1159/000052475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marks L, Roehrborn C, Andriole G. Prevention of benign prostatic hyperplasia disease. J Urol. 2006;176:1299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Oliver OM, et al. The long term effect of doxazosin, finasteride and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2385–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roehrborn CG, Siami P, Barkin J, et al. The effects of dutasteride, tamsulosin, and combination therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate enlargement: Two-year results from the CombAT study. J Urol. 2008;179:616–21. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barkin J, Guimares M, Joacobi G, et al. Alpha blocker therapy can be withdrawn in the majority of men following initial combination therapy with the dual 5-alpha reductase inhibitor dutasteride. Eur Urol. 2003;44:461–6. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nickel JC, Barkin J, Koch C, et al. Finasteride monotherapy maintains stable lower urinary tract symptoms in men with BPH following cessation of alpha blockers. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2:16–21. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, et al. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2319–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tubaro A, Batista JE, Nitti VW, et al. Efficacy and safety of daily mirabegron 50 mg in male patients with overactive bladder: A critical analysis of five phase 3 studies. Ther Adv Urol. 2017;10:9. doi: 10.1177/1756287217702797. :137–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drake MJ, Chapple C, Sokol R, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of single-tablet combinations of solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in men with storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from the NEPTUNE Study and NEPTUNE II open-label extension. Eur Urol. 2015;67:262–70. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichihara K, Masumori N, Fukuta F, et al. A randomized controlled study of the efficacy of tamsulosin monotherapy and its combination with mirabegron for overactive bladder induced by benign prostatic obstruction. J Urol. 2015;193:921–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.09.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oelke M, Giuliano F, Mirone V, et al. Monotherapy with tadalafil or tamsulosin similarly improved lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in an international, randomized, parallel, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2012;61:917–25. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss JP, Herschorn S, Albei CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of low dose desmopressin orally disintegrating tablet in men with nocturia: Results of a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, parallel group study. J Urol. 2013;190:965–72. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Habib FK, Wyllie MG. Not all brands are created equal: A comparison of selected components of different brands of Serenoa repens extract. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2004;7:195–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barry MJ, Meleth S, Kreder KH, et al. Effect of increasing doses of saw palmetto on lower urinary tract symptoms: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306:1344–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tacklind J, Macdonald R, Rutks I, et al. Serenoa repens for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:Cd001423. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001423.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilt T, Ishani A, Mac Donald R, et al. Pygeum africanum for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:Cd001044. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornu JN, Ahyai S, Bachmann AJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic obstruction: An update. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1066–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reich O, Gratzke C, Backmann A, et al. Morbidity, mortality, and early outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate: A prospective, multicentre evaluation of 10 654 patients. J Urol. 2008;180:246–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahyai SA, Gilling P, Kaplan SA, et al. Meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic enlargement. Eur Urol. 2010;58:384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mamoulakis C, Sofras F, de la Rosette J, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD009629. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009629.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geavlete B, Georgescu D, Multescu R, et al. Bipolar plasma vaporization vs. monopolar and bipolar TURP: A prospective, randomized, long-term comparison. Urology. 2011;78:930–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muslumanoglu AY, Yuruk E, Binbay M, et al. Transurethral resection of prostate with plasmakinetic energy: 100 months results of a prospective, randomized trial. BJU Int. 2012;110:546–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varkarakis I, Kyriakakis Z, Delis A, et al. Long-term results of open transvesical prostatectomy from a contemporary series of patients. Urology. 2004;64:306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin Y, Wu X, Xu A, et al. Transurethral enucleation of the prostate vs. transvesical open prostatectomy for large benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Urol. 2016;34:1207–19. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Autorino R, Zargar H, Mariano MB, et al. Perioperative outcomes of robotic and laparoscopic simple prostatectomy: A European-American multi-institutional analysis. Eur Urol. 2015;68:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naspro R, Suardi N, Salonia A, et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate vs. open prostatectomy for prostates >70 g: 24-month followup. Eur Urol. 2006;50:563–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilling PJ, Wilson LC, King CJ, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing holmium laser enucleation of the prostate and transurethral resection of the prostate: Results at 7 years. BJU Int. 2012;109:408–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elzayat EA, Elhilali MM. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP): Long-term results, reoperation rate, and possible impact of the learning curve. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1465–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas JA, Tubaro A, Barber N, et al. A multicentre, randomized, non-inferiority trial comparing GreenLight-XPS laser vaporization of the prostate and transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic obstruction: Two-year outcomes of the GOLIATH study. Eur Urol. 2016;69:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ajib K, Mansoura M, Zanaty M, et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate with the 180-W XPS-Greenlight laser: Five-year experience of safety, efficiency, and functional outcomes. Can Urol Assoc J. 2018;12:E318–24. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruszat R, Seitz M, Wyler SF, et al. Prospective single-centre comparison of 120-W diode-pumped, solid-state, high-intensity system laser vaporization of the prostate and 200-W high-intensive diode-laser ablation of the prostate for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2009;104:820–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiang PH, Chen CH, Kang CH, et al. GreenLight HPS laser 120-W vs. diode laser 200-W vaporization of the prostate: Comparative clinical experience. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:624–9. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gross AJ, Netsch C, Knipper S, et al. Complications and early postoperative outcome in 1080 patients after thulium vapoenucleation of the prostate: Results at a single institution. Eur Urol. 2013;63:859–67. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rausch S, Heider T, Bedke J, et al. Analysis of early morbidity and functional outcome of thulium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser enucleation for benign prostate enlargement: Patient age and prostate size determine adverse surgical outcome. Urology. 2015;85:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lourenco T, Shaw M, Fraser C, et al. The clinical effectiveness of transurethral incision of the prostate: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. World J Urol. 2010;28:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de la Rosette J, Laguna MP, Gravas S, et al. Transurethral microwave thermotherapy: The gold standard for minimally invasive therapies for patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia? J Endourol. 2003;17:245–51. doi: 10.1089/089277903765444393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.D’Ancona FC, van der Bij AK, Francisca EA, et al. Results of high-energy transurethral microwave thermotherapy in patients categorized according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists operative risk classification. Urology. 1999;53:322–8. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gravas S, Laguna P, Kiemenen LA, et al. Durability of 30-minute high-energy transurethral microwave therapy for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A study of 213 patients with and without urinary retention. Urology. 2007;69:854–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boyle P, Robertson C, Vaughan ED, et al. A meta-analysis of trials of transurethral needle ablation for treating symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2004;94:83–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bouza C, Lopez T, Magro A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of transurethral needle ablation in symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. BMC Urol. 2006;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vanderbrink BA, Rastinehad AR, Badlani G. Prostatic stents for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:1–6. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3280117747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Senksen J, Barber NJ, Speakman MJ, et al. Prospective, randomized, multinational study of prostatic urethral lift vs. transurethral resection of the prostate: 12-month results from the BPH6 study. Eur Urol. 2015;68:643–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roehrborn CG, Barkin J, Gange SN, et al. Five-year results of the prospective, randomized controlled prostatic urethral L.I.F.T. study. Can J Urol. 2017;24:8802–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McVary KT, Gange SN, Gittelman MC, et al. Minimally invasive prostate convective water vapour energy ablation: A multicentre, randomized controlled study for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2016;195:1529–38. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.10.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McVary KT, Gange SN, Gittelman MC, et al. Erectile and ejaculatory function preserved with convective water vapour energy treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: Randomized controlled study. J Sex Med. 2016;13:924–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roehrborn CG, Gange SN, Gittelman MC, et al. Convective radiofrequency water vapour thermal therapy with rezum system: Durable two-year results of randomized controlled and prospective crossover studies for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2017;197:1507–16. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gilling P, Anderson P, Tan A. Aquablation of the prostate for symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: One-year results. J Urol. 2017;197:1565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gilling P, Barner N, Bidair M, et al. WATER: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial of aquablation vs. transurethral resection of the prostate in benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2018;199:1252–61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Porpiglia F, Fiori C, Bertolo R, et al. Temporary implantable nitinol device (TIND): A novel, minimally invasive treatment for relief of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) related to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): Feasibility, safety, and functional results at one year of followup. BJU Int. 2015;116:278–87. doi: 10.1111/bju.12982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pisco JM, Rio Tinto H, et al. Embolization of prostatic arteries as treatment of moderate to severe lower urinary symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign hyperplasia: Results of short- and midterm followup. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:2561–72. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2714-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carnevale FC, Iscaife A, Yoshinaga EM, et al. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) versus original and PErFecTED prostate artery embolization (PAE) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (bph): Preliminary results of a single-centre, prospective, urodynamic-controlled analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39:44–52. doi: 10.1007/s00270-015-1202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao YA, Huang Y, Zhang R, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: Prostatic arterial embolization vs. transurethral resection of the prostate — a prospective, randomized, and controlled clinical trial. Radiology. 2014;270:920–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shim SR, Kanhai KJ, Ko YM, et al. Efficacy and safety of prostatic arterial embolization: Systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Urol. 2017;197:465–79. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Russo GI, Kurbatov D, Sansalone S, et al. Prostatic arterial embolization vs. open prostatectomy: A one-year matched-pair analysis of functional outcomes and morbidities. Urology. 2015;86:343–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lucas MG, Stephenson TP, Nargund V. Tamsulosin in the management of patients in acute urinary retention from benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2005;95:354–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McNeill SA, Hargreave TB, Roehrborn CG Alfaur study group. Alfuzosin 10 mg once daily in the management of acute urinary retention: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Urology. 2005;65:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patel SB, Ranka K, Kundargi VS, et al. Comparison of tamsulosin and silodosin in the management of acute urinary retention secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients planned for trial without catheter. A prospective, randomized study. Cent European J Urol. 2017;70:259–63. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2017.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the Standardization Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–78. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chapple CR, Osman NI, Birder L, et al. The underactive bladder: A new clinical concept? Eur Urol. 2015;68:351–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Potts B, Belsante M, Peterson A, et al. Bladder outlet procedures are an effective treatment for patients with urodynamically confirmed detrusor underactivity without bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2016;195:e975. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.02.1712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Delakas D, Lianos E, Karyotis I, et al. Finasteride: A long-term followup in the treatment of recurrent hematuria associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Int. 2001;67:69–72. doi: 10.1159/000050948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thompson IN, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride in the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:211–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Andriole GL, Bostwick DG, Brawley OW, et al. Effect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1192–202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grubb RL, Andriole G, Sommerville MC, et al. The REDUCE followup study: Low rate of new prostate cancer diagnosis observed during a two-year, observational followup study of men who participated in the REDUCE trial. J Urol. 2013;189:871–977. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Klotz L, Chetner M, Chin J, et al. Canadian consensus conference: The FDA decision on the use of 5ARIs. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:83–8. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]