Abstract

Introduction

Treatment using abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, enzalutamide, cabazitaxel, and radium-223 (Ra-223) improves overall survival (OS) and quality of life for patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Despite their proven benefits, access to these therapies is not equal across Canada.

Methods

We describe provincial differences in access to approved mCRPC therapies. Data sources include the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review database, provincial cancer care resources, and correspondence with pharmaceutical companies.

Results

Both androgen receptor-axis-targeted therapies (ARATs), abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide, are funded by provinces in the pre-and post-chemotherapy setting, however, sequential ARAT use is not funded. “Sandwich” therapy, where one ARAT is used pre-chemotherapy and a second is used upon progression on chemotherapy, is funded in six provinces: Ontario (ON), Alberta, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island (PEI), Nova Scotia (NS), and Newfoundland and Labrador. Ra-223 is funded in five provinces: ON, Quebec (QC), British Columbia (BC), Saskatchewan, and Manitoba to varying degrees; ON allows Ra-223 either pre- or post-chemo (not both); QC allows Ra-223 post-chemo unless chemo is not tolerated; BC allows Ra-223 if other life-prolonging mCRPC therapies have been received or ineligible. Cabazitaxel is funded in all provinces post-docetaxel, except QC and PEI. Cabazitaxel is not funded as fist-line treatment for mCPRC or in combination with other agents. In ON, BC, QC, and PEI, cabazitaxel is not funded after progression on an ARAT in the post-chemotherapy setting.

Conclusions

While all provinces have access to docetaxel and ARATs, sandwiching sequential ARATs with docetaxel is funded only in select provinces. Ra-223 and cabazitaxel access is not ubiquitous across Canada. Such inequalities in access to life-prolonging therapies could lead to disparities in survival and quality of life among patients with mCRPC. Further research should quantify interprovincial variation in outcomes and cost that may result from variable access.

Introduction

For men whose prostate cancer recurs after local therapy or who present with metastatic disease, no curative options exist. The standard treatment is androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), either in the form of surgical or medical castration. ADT is effective in relieving symptoms and has been demonstrated to delay disease progression, but eventually all patients will progress to castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Progression may present as a rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels despite castrate levels of testosterone (<50 ng/dl, 1.73 mmol/L), symptomatic progression, or the radiographical appearance of new metastases.

Prior to 2010, docetaxel-based chemotherapy was the only agent with proven ability to prolong overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic CRPC (mCRPC); median OS was improved by 2.4 months with docetaxel and prednisone compared to mitoxantrone and prednisone.1

Since 2010, there has been exponential growth in treatments available for mCRPC. There are now four Health Canada-approved therapies, all of which have shown improvements in OS (Table 1). Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide are new androgen receptor axis-targeted (ARAT) agents. Cabazitaxel is a microtubule stabilizing chemotherapeutic agent and radium-223 (Ra-223) is a radio-pharmaceutical that improves OS and reduces symptomatic skeletal events (SSEs).

Table 1.

Novel agents in mCRPC treatment, their associated overall survival benefits, and common side effects

| Treatment | Overall survival (OS) benefit | Common side effects (Grade 3–4) |

|---|---|---|

| Enzalutamide (Xtandi®, Astellas) | Fatigue, back pain, arthralgia, and hypertension15 | |

| Pre-docetaxel | 4.0 months compared with placebo15 | |

| Post-docetaxel | 4.8 months compared with placebo16 | |

| Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone (Zytiga®, Janssen) | Anaemia, liver function test abnormalities, hypokalemia, and fluid retention17 | |

| Pre-docetaxel | 4.4 months compared with placebo17 | |

| Post-docetaxel | 4.6 months compared with placebo18 | |

| Docetaxel (Taxotere®, Sanofi) | 2.4–3.0 months compared with mitoxantrone1,19 | Neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue |

| Cabazitaxel (Jevtana®, Sanofi) | 2.4 months compared with mitoxantrone20 | Neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue |

| Radium-223 (Xofigo®, Bayer) | 3.6 months compared with placebo11 | Anemia, neutropenia thrombocytopenia, and bone pain |

mCRPC: metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

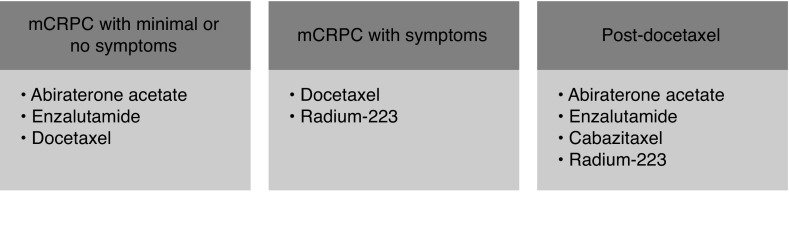

Contemporary management of mCRPC is complex and is constantly evolving. A summary of the current Canadian Urological Association-Canadian Urologic Oncology Group (CUA-CUOG) guideline supporting the use of the agents discussed in this study is shown in Fig. 1.2 Unfortunately, access to these mCPRC agents globally is variable.

Fig. 1.

Canadian Urological Association-Canadian Urological Oncological Group 2015 guideline on the management of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).2

Even within Canada’s publicly funded health system, there is interprovincial variation in access to treatments for mCRPC. Because of the importance of inequity in access to life-prolonging treatments within a national health system, the Canadian Genitourinary Research Consortium (GURC), a collaborative network of community and academic uro-, medical, and radiation oncologists, prioritized this issue as an important barrier to best practice and set out to undertake a descriptive analysis of interprovincial funding policies for mCRPC treatments. The GURC also conducted a survey of uro-, radiation, and medical oncologists specialized in the care of patients with advanced prostate cancer to understand real-world preferences and barriers encountered in access to mCRPC treatments.

In this paper, we describe the specific nuances of mCRPC therapy availability in each province to characterize the interprovincial disparities in access, explore barriers and potential consequences this disparity may introduce, and contrast the access with treatment preferences and perceived barriers as reported in the Canadian GURC survey.3

Methods

Information sources

To characterize the nuances of access to mCRPC therapies across Canada, we interrogated the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR) provincial funding summaries.4 pCODR is an evidence-based cancer drug review program that conducts thorough and objective evaluations of clinical, economic, and patient-based evidence on Health Canada-approved cancer drugs to provide reimbursement recommendations to provincial public drug plans and cancer agencies. The drug plans and cancer agencies make their final reimbursement and coverage decisions based on the CADTH recommendations and other factors, such as their program mandates, jurisdictional priorities, and budget impact. Provincial funding decisions and criteria are summarized as, “Provincial Funding Summaries” on the pCODR website after posting their reimbursement recommendations.4

Quebec does not participate in the pCODR process and thus information came solely from provincial formulary sources and pharmaceutical companies. Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut were excluded from this study due to their small population size and because limited information could be obtained from available sources. As Ra-223 has not been reviewed by the pCODR, funding status in each of the provinces was obtained directly from the company (Bayer Inc.).

Supplemental information sources included: provincial cancer care guidelines and formularies; pharmaceutical manufacturers who are market authorization holders for the treatments in Canada; and the GURC network of clinicians who treat mCRPC in their provinces.

Descriptive analysis of interprovincial disparity

Funding decisions and reimbursement criteria are described by province and we have characterized the nuances of access to mCRPC therapies across Canada, highlighting where disparities and commonalities exist.

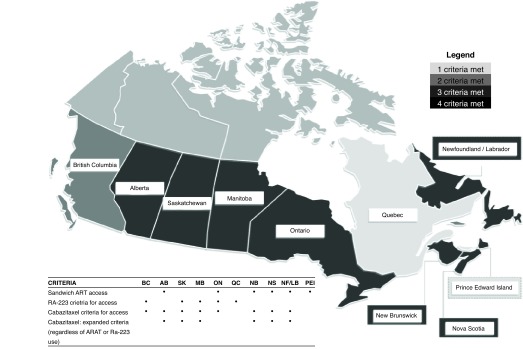

To summarize pictographically the interprovincial variation in access, we developed a heat map that reflects the key differentiating factors related to access across the provinces as a composite score or shade.

In order to examine current treatment access to drugs against real-world patterns of treatment and issues with treatment access, we also examined preferred treatment practice patterns and barriers to treatment access as reported from the GURC Canadian survey of uro-, radiation, and medical oncologists specialized in the care of patients with advanced prostate cancer. 5

Results

ARAT

Both abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide are currently funded by all provinces in pre- and post-chemotherapy mCRPC patients, with minor variations in criteria between abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide. However, disparities across provinces exist in access to ARAT therapy for use both pre-docetaxel and post-docetaxel (“sandwich therapy,” see below) and no provinces allow use of sequential ARAT therapy unless intolerance is encountered.

Enzalutamide

In general, in patients with chemo-naive mCRPC, enzalutamide is funded across Canada for asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with no risk factors for seizures. However, minor variations in the criteria do exist between the provinces (Table 2). For example, in Manitoba, prescribers need to be affiliated with a cancer centre; in Alberta, only approved designated physicians can prescribe enzalutamide; and in British Columbia, patients must have three months life expectancy.

Table 2.

Funding criteria for enzalutamide in each province

| Province | Enzalutamide | Symptomatic | ECOG status | Is “sandwich” therapy allowed? | Exclusion criteria | Other criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | Risk factors for seizures Disease progression on enzalutamide |

Switching from abiraterone acetate plus prednisone to enzalutamide in patients who have not progressed on abiraterone acetate plus prednisone is considered on a case-by-case basis | |

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | Yes | Risk factors for seizures | May approve enzalutamide use after cabazitaxel or abiraterone acetate plus prednisone provided no progression has occurred in 3 months | ||

|

| ||||||

| Quebec | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | No | Prior enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate plus prednisone treatment | |

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | No | Prior enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate plus prednisone treatment | |||

|

| ||||||

| Alberta | Chemo-naive | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | Enzalutamide is prescribed by approved designated prescribers only | |||

| Post-docetaxel | Yes | Prior enzalutamide | ||||

|

| ||||||

| British Columbia | Pre-docetaxel | 0–2 | Life expectancy >3 months | |||

| Post-docetaxel | No | Prior enzalutamide | Only one ARAT is funded | |||

|

| ||||||

| Saskatchewan | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | ||||

| Post-docetaxel | Symptomatic | 0–1 | No | |||

|

| ||||||

| Manitoba | Pre-docetaxel | Prescribers need to be affiliated with a cancer centre Histologically confirmed mCRPC with disease progression |

||||

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | No | Risk factors for seizures | Prescribers need to be affiliated with a cancer centre | ||

|

| ||||||

| Nova Scotia | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | Risk factors for seizure | ||

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | Yes | Risk factors for seizure | |||

|

| ||||||

| New Brunswick | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0 | Risk factors for seizure | ||

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | Yes | Risk factors for seizure | |||

|

| ||||||

| Prince Edward Island | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | |||

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | Yes | Risk factors for seizure | |||

|

| ||||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | Risk factors for seizure | ||

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | Yes | Risk factors for seizure | Approval period: 4 months Renewal will only be approved if there is no evidence of progression of disease and the development of unacceptable toxicities | ||

ARAT: androgen receptor-axis-targeted therapies; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mCRPC: metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

In the post-docetaxel setting, for patients who have not yet received an ARAT, enzalutamide is reimbursed across Canada. For patients who received enzalutamide prior to docetaxel, enzalutamide is not funded in the post-docetaxel setting. In Newfoundland and Labrador, approval must be renewed every four months, with no evidence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicities.

Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone

Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone is funded across Canada for patients with asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic mCRPC in both pre- and post-docetaxel settings (Table 3). Ontario and British Columbia have specific criteria regarding hepatic, cardiac, or renal function for eligibility. In Ontario, funding is ceased upon disease progression. Similar restriction probably exists in other provinces, but is not documented in the pCODR’s provincial funding summary.

Table 3.

Funding criteria for abiraterone acetate plus prednisone for each province

| Province | Abiraterone acetate + prednisone | Symptomatic | ECOG status | Is “sandwich” therapy allowed? | Exclusion criteria | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | Viral hepatitis, chronic liver disease, clinically significant heart disease Disease progression while on abiraterone acetate plus prednisone |

||

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | Yes | Same as pre-docetaxel | Requests for patients who initiated cabazitaxel or enzalutamide therapy within the 3 months preceding the EAP request for abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and who have not had disease progression will be considered on a case-by-case basis | ||

|

| ||||||

| Quebec | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | Prior enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate plus prednisone treatment | ||

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | No | Prior enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate plus prednisone treatment | |||

|

| ||||||

| Alberta | Pre-docetaxel | Symptomatic | mCRPC agents are prescribed by approved designated prescribers only | |||

| Post-docetaxel | Yes | Prior enzalutamide | ||||

|

| ||||||

| British Columbia | Pre-docetaxel | 0–1 | Prior enzalutamide | Adequate renal and liver function and serum potassium levels | ||

| Post-docetaxel | Symptomatic and ineligible for docetaxel | 0–2 | No | Prior enzalutamide | It will be funded if the patient is ineligible for docetaxel as assessed by a medical oncologist (e.g., >80 yo, comorbid conditions) | |

|

| ||||||

| Saskatchewan | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | Prior enzalutamide | |||

| Post-docetaxel | Symptomatic | No | If the patient is not a candidate for docetaxel | |||

|

| ||||||

| Manitoba | Pre-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | 0–1 | Disease progression during treatment with prior enzalutamide | Prescribers need to be affiliated with a cancer centre | |

| Post-docetaxel | 0–2 | No | Same as pre-docetaxel | Same as pre-docetaxel | ||

|

| ||||||

| New Brunswick | Pre and post-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | Yes | |||

|

| ||||||

| Prince Edward Island | Pre and post-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | Yes | mCRPC agents are prescribed by approved designated prescribers only | ||

|

| ||||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Pre and post-docetaxel | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic | Yes | |||

EAP: Exceptional access program; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mCRPC: metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

In Manitoba, prescribers need to be affiliated with a cancer centre. In Alberta and Prince Edward Island, only approved designated physicians can prescribe. For example, in Prince Edward Island, coverage must be requested by a specialist in hematology or medical oncology or a general practitioner acting under the direction of those specialists.

In the post-docetaxel setting, for patients who have never received an ARAT, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone is reimbursed across Canada. For patients who had abiraterone acetate plus prednisone before, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone is not funded in the post-docetaxel setting.

Sequential and/or “sandwich” ARAT use

While provinces generally use similar criteria for use of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide, there are differences across provinces in funding of ARAT for sequential or “sandwich” use. Across Canada, only one ARAT agent is funded in the pre-docetaxel setting. If progression on one agent is documented, no province will fund another ARAT to be used sequentially (ARAT followed by ARAT). In Ontario, if patients discontinue the first-line ARAT because of intolerable adverse effects within three months, and there is no documented disease progression, switching to a second ARAT is considered on a case-by-case basis in the pre-docetaxel setting.

If an ARAT was not used in the pre-docetaxel setting, it is funded for post-docetaxel use. However, similar principles apply in that sequential ARAT use is not funded, with the exception of Ontario, where a switch can be made because of adverse effects.

Importantly, some provincial agencies fund the use of a second ARAT after a prior ARAT, provided chemotherapy was used in between (e.g., abiraterone acetate plus prednisone – docetaxel – enzalutamide). This so-called “sandwich therapy” is allowed in Ontario, Alberta, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador (one half of Canadian provinces), and is indicated Tables 2 and 3.

Ra-223

Ra-223 was not reviewed by pCODR, leaving each province to review it independently. It is currently funded in Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba (Table 4), leaving approximately 20% of Canadians without coverage. In general, funding covers symptomatic bone metastases with no visceral metastatic disease. In Ontario, combination with other novel agents (enzalutamide, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, or cabazitaxel) is not funded; and if Ra-223 is funded in the pre-docetaxel setting, no further funding is available in the post-docetaxel setting. The other four provinces probably have similar restrictions, but it is not explicitly stated.

Table 4.

Public funding criteria for radium-223 in for each province

| Province | Soft tissue metastasis criteria | ECOG | Combination with other CRPC treatments | Other requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | No known visceral metastatic disease | Cannot be combined with cabazitaxel or enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate plus prednisone for mCRPC If radium-223 is funded in the pre-docetaxel setting, no subsequent funding will be considered in the post-docetaxel setting |

A consultation with a medical or radiation oncologist has been done before starting radium-223 | |

|

| ||||

| Quebec | No known visceral metastatic disease | 0–2 | Will only be funded if the disease has progressed during or following docetaxel unless there is severe contraindication or serious intolerance | |

|

| ||||

| British Columbia | Patients have no known liver, lung, or brain metastases and no known symptomatic soft tissue metastases (lymph nodes, local disease, etc.) | 0–2 | Will only be funded if patients already received, are not eligible for, decline, or have no access to other life-prolonging treatment options (e.g., docetaxel, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, enzalutamide | Recently seen by a medical oncologist |

|

| ||||

| Saskatchewan | No known visceral metastatic disease | 0–2 | Recently seen by a medical oncologist Hemoglobin >100 g/L; | |

| Lymphadenopathy <3 cm | Platelets >100×109/L; ANC >1.5×109/L | |||

| No untreated spinal cord compression or fracture requiring orthopedic stabilization | Subsequent doses: Platelets >50×109/L; ANC >1×109/L | |||

|

| ||||

| Manitoba | ||||

ANC: absolute neutrophil count; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mCRPC: metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

Chemotherapy: Docetaxel and cabazitaxel

Docetaxel is funded across Canada without restriction. Cabazitaxel, used after docetaxel, is currently funded by all provincial drug programs except Quebec and Prince Edward Island (Table 5). No Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) or clinical status requirements are stated. However, cabazitaxel is not funded if it is used in combination with other novel agents or as first-line therapy for mCRPC. In Ontario, British Columbia, Quebec, and Prince Edward Island, cabazitaxel is also not funded if a patient has received abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, enzalutamide, or RA-223 in the post-docetaxel setting, but if a patient fails on abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or enzalutamide, switching to cabazitaxel is often allowed within three months of starting the ARATs.

Table 5.

Public funding approval for radium-223, docetaxel, and cabazitaxel in each province

| Province | Radium-223 | Docetaxel | Cabazitaxel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Quebec | Yes | Yes | No |

| Alberta | No | Yes | Yes |

| British Columbia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Saskatchewan | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Manitoba | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nova Scotia | No | Yes | Yes |

| New Brunswick | No | Yes | Yes |

| Prince Edward Island | No | Yes | No |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | No | Yes | Yes |

Heat map of interprovincial access

Fig. 2 represents our consensus summary of each province’s access to mCRPC therapies, with dark grey representing greater access and light grey representing less access.

Fig. 2.

Pictographic description of variation in interprovincial access to life-prolonging therapies in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. ARAT: androgen receptor-axis-targeted therapies; Ra: radium.

Preferred lines of therapy vs. interprovincial access

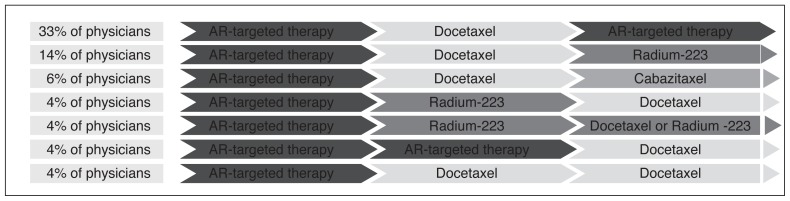

Based on a recent Canadian survey conducted by the GURC, ARAT was reported as the preferred first-line therapy for mCRPC, followed by docetaxel second-line and an ARAT or Ra-223 as the third-line treatment (Fig. 3). Cabazitaxel was the therapy used most as fourth-line therapy, along with Ra-223.5

Fig. 3.

Real-world line 1 to line 3 treatment sequencing in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. *The remaining lines of treatment sequencing are not shown due to small numbers. AR: androgen receptor.

However, real-world preferences reported by the survey respondents showed a disconnect between preferred access and actual access to mCRPC treatment. Nearly two-thirds of physicians (65%) cited limitations related to ARAT access, followed by 59% for cabazitaxel, and 45% for Ra-223.

Discussion

The landscape of prostate cancer care has changed dramatically in the last eight years. With four new agents, each proven to prolong survival, treatment options for patients entering mCRPC are now plentiful and provide options to use therapies in sequence. However, access to these new agents globally is variable and, as we observed in our study, disparities exist across provinces in Canada.

Docetaxel is funded in all provinces without restriction. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone and enzalutamide are funded by all provinces in the pre-and post-chemotherapy settings, however, sequential use is not funded in any province, and the use of one ARAT pre-chemotherapy and the other ARAT post-chemotherapy (sandwich therapy) is not funded in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, or Quebec. Cabazitaxel use after docetaxel is funded in all provinces except Quebec and Prince Edward Island. The greatest disparity was noted for government-funded access to Ra-223, where funding was available in only five provinces. In our survey of provincial funded therapies, the most desired therapy sequence was an ARAT followed by docetaxel, followed by another ARAT. However, such sandwich therapy is only funded in six provinces.

Combined, there are clearly provinces that fund more treatment options and there are provinces with relatively limited treatment access. Such inequalities in access to life-prolonging therapies could lead to differences in survival and quality of life among patients with mCRPC and calls into question if such inequalities should persist in a country with universal healthcare. Although one of the goals of the Canada Health Act, adopted in 1984, was to equalize the level of care across the provinces, it did not specify how healthcare should be organized and/or delivered; this is left to the jurisdiction of the provinces and this includes decisions pertaining to medication coverage.6 For a new therapy to be approved for sale in Canada, a pharmaceutical company must first apply to Health Canada, which then reviews published data on the agent’s safety and clinical effectiveness. Following approval by Health Canada, pCODR evaluates the scientific evidence and the associated cost to decide if the new cancer therapy is clinically efficacious and cost-effective.4 pCODR will then provide public funding recommendations to the provinces, with the exception of Quebec, where this process is conducted by the Institute National d’Excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux.7 pCODR recommendations are not binding.8 Each provincial Ministry of Health and cancer agency makes independent decisions on treatment funding. Therefore, a delay or rejection of funding by individual provinces can create a serious impediment or even lack of access to new treatments for provincial residents. Disparity is well-documented in other cancer drug funding. The use of adjuvant hormonal therapy to lower breast cancer recurrence risk,9 and use of monoclonal antibodies in metastatic colorectal cancer10 are some examples. In provinces where these new therapies are not funded publicly, patients may still be able to access them through private health insurance, out-of-pocket pay, or through compassionate drug release programs.

The new agents for mCRPC certainly improve outcomes for patients, but they are expensive and this is likely the most influential reason why all provinces have not agreed to fund all therapies. For example, based on the information from pharmaceutical companies, the cost per 28-day cycle for docetaxel, abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, enzalutamide, Ra-223, and cabazitaxel are $1217, $3551, $3270, $5640, and $7738, respectively.

Disparity in public access to Ra-223 is interesting, as we observed the greatest disparity here; only five provinces offer any coverage. Current estimates suggest 20% of Canadian men cannot receive this treatment due to lack of funding. This may be, in part, because Ra-223 was the last of the new agents to seek Health Canada approval. It may also be because, as a radiopharmaceutical, Ra-223 did not go through the usual pCODR process. Yet, it is currently the only bone-targeting agent with proven OS benefit.11 Furthermore, it reduces the risk of SSEs that are known to cause significant morbidity, mortality, and cost.12–14 A Canadian study suggested the annual cost of patients with metastatic bone disease was $11 820 CAD more than those without, and these costs were mostly attributable to resource utilization secondary to SSEs. Thus, it could be argued that patients in the provinces without access to Ra-223 are placed at a notable health disadvantage, and there may be a role for Canadian-based cost-effectiveness studies to determine if funding Ra-223 could potentially be cost-neutral or cost-saving.

Our findings suggest a problem of inequality across Canada. Advanced prostate cancer is but one model to study this problem, however it is a particularly sensitive model, as the landscape is changing rapidly. More drugs with proven survival benefit are forthcoming. The drugs are being tested in earlier disease stages and translating into life-prolongation, meaning patients will be on the drugs for significantly longer periods.

Our study has some limitations. The accuracy of information for certain drugs in certain provinces (e.g., Ra-223 in Manitoba) is not entirely clear, as the provinces may not have released all approval details. To combat this, we requested additional information from pharmaceutical companies and have spoken to providers in those provinces to validate information. Information on drug coverage was not available for the territories, however, this represents <0.01% of the Canadian population. Finally, our study merely captured drug funding. What remains unknown is the actual interprovincial use and whether access also translates into improvements in survival and quality of life between provinces.

Conclusion

Provincial access to approved mCRPC therapies varies across Canada. While access to docetaxel and ARATs was mostly ubiquitous, there were funding differences that hinder the ability to optimally sequence these agents the way providers would ideally like. Cabazitaxel after docetaxel is not approved in Quebec or Prince Edward Island. However, the greatest disparity was observed with Ra-223, where five provinces, comprising approximately 20% of the Canadian population, currently do not have access.

While men with mCRPC are living longer, the cost of treating advanced prostate cancer is rising, which could lead to a widening of interprovincial inequality. Further studies are needed to explore the cost-effectiveness of these drugs in a Canadian setting and whether survival and quality of life is significantly superior in the provinces with high access, as compared to those with limited access.

Acknowledgement

Disparity analysis was funded by Janssen Inc.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Aaron has attended advisory boards for AbbVie and Janssen; has been a speaker for Ferring and Janssen; holds investments in Johnson & Johnson; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Asetllas, Ferring, and Janssen. Dr. Basappa has attended advisory boards for Astellas, AstraZeneca, BI, BMS, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer; and has received honoraria from Astellas, BMS, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer. Dr. Chi has received grants/honoraria from Astellas, Bayer, Essai, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Essai, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, and Sanofi. Dr. Gotto has attended advisory boards for and received honoraria from Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, BMS, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi; and has participated in the following clinical trials: ARAMIS, COSMIC, EMBARK, ENZAMET, HERO, SPARTAN, and TITAN. Dr. Saad has attended advisory boards for and has received payment/honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, and Sanofi. Dr. Shayegan has received grants/honoraria from AbbVie, Astellas, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas and Janssen. Ms. Park-Wyllie is employed by Janssen Canada. The remaining authors report no competing personal or financial interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saad F, Chi KN, Finelli A, et al. The 2015 CUA-CUOG guidelines for the management of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9:90–6. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotte JH, Finelli A, Malone S, et al. Real-world patterns of treatment sequencing in Canada for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl 6S) abstr 320. [Google Scholar]

- 4.pan-Canada Oncology Drug Review (pCORD) provincial funding summaries. [Accessed Aug. 30, 2018]. Available at https://cadth.ca/pcodr.

- 5.Shayegan B, So A, Malone S, et al. Patterns of prostate cancer management across Canadian prostate cancer treatment specialists. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl 6S) abstr 321. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canada Health Act. RSC; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux. [Accessed Aug. 30, 2018]. Available at http://www.inahta.org/members/inesss/

- 8.Vogel L. Pan-Canadian review of cancer drugs will not be binding on provinces. CMAJ. 2010;182:887–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma S, Sehdev S, Joy AA. Cancer therapy disparity: Unequal access to breast cancer therapeutics and drug funding in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2007;14( Suppl1):S3–10. doi: 10.3747/co.2007.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry SR, Evans WK, Strevel EL, et al. Variation and consternation: access to unfunded cancer drugs in Canada. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:35–9. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DePuy V, Anstrom KJ, Castel LD, et al. Effects of skeletal morbidities on longitudinal patient-reported outcomes and survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:869–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue T, Segawa T, Kamba T, et al. Prevalence of skeletal complications and their impact on survival of hormone refractory prostate cancer patients in Japan. Urology. 2009;73:1104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinfurt KP, Li Y, Castel LD, et al. The significance of skeletal-related events for the health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:579–84. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf D, et al. Enzalutamide in men with chemotherapy-naïve metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Extended analysis of the phase 3 PREVAIL study. Eur Urol. 2017;7:151–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone vs. placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): Final overall survival analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:152–60. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Bono J, Logothetis C, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomized, open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]