Abstract

Background:

Intensification of systemic therapy for high-risk neuroblastoma (HRNB) has resulted in improved local control and overall survival leaving potential for de-escalation of primary site radiotherapy. The utility of primary site de-escalation should be evaluated in the context of potential for successful local-regional salvage. We evaluated salvage strategies and outcomes in HRNB patients with local-regional recurrence as a component of first failure.

Methods:

Twenty of 89 patients with HRNB experienced local-regional recurrence as a component of first relapse after chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, and stem cell transplant from 1997–2013. We reviewed salvage therapy strategies and disease control, and report on the impact of local therapy as salvage for local-regional relapse.

Results:

Six of 20 patients with local-regional failure (LRF) were alive after a median follow-up of 13 years (range, 0.9–25.2 years). Median overall survival (OS) was 4.6 years (95% CI, 0.6 – not reached) vs. 0.6 years (95% CI, 0.05–2.6) after LRF with and without distant failure (DF) respectively (p=0.03). Overall survival in patients receiving salvage radiotherapy was comparable to those receiving initial adjuvant but no salvage radiotherapy. Time to first failure and death was significantly impacted by the intensity of frontline systemic therapy (p=0.03). Salvage radiotherapy reduced the hazard for subsequent LRF (HR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.9, p=0.04) but not OS (p=0.07).

Conclusions:

Our study highlights the potential of local control strategies at first failure in patients with LRF when primary site radiotherapy was initially omitted, and delineates potential selection factors which may further improve the therapeutic ratio.

Keywords: Salvage, High-risk neuroblastoma, Radiation, Local-Regional

INTRODUCTION

Up to 60% of children with HRNB will experience disease progression within 18 months of frontline therapy.1 At recurrence, therapeutic options are often limited given the intensity of initial therapy, high rate of multifocal distant recurrence, and limited response rates to salvage chemotherapy.1 Studies detailing the role of local therapy including surgery and radiotherapy at recurrence are sparse, so clinicians must rely on their institutional experience and clinical judgment to decide who should have local regional therapies used as a component of salvage. Several studies have evaluated alternative forms of radiotherapy in previously irradiated patients, such as intraoperative radiotherapy and stereotactic body radiotherapy, for use at salvage either as re-irradiation or at new sites of disease.2–4 Given that few studies have evaluated the utility of salvage radiotherapy as a component of local therapy in HRNB patients with a component of local-regional relapse as first failure, we evaluated the outcomes and management strategies utilized in a cohort of HRNB patients treated on prospective trials with varying intensities of front line systemic therapy who had local-regional relapse as a component of first failure.

METHODS

Patient population and data abstraction

This study was reviewed and approved in accordance with the policies of the Institutional Review Board of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH). We identified 20 patients with locoregional recurrence with or without concomitant distant failure after initiating frontline therapy among 89 consecutively treated patients with HRNB, according to Children’s Oncology Group Risk (COG) risk stratification criteria, between 1997 and 2013. Patient characteristics including initial treatment, disease characteristics, salvage therapy, and outcomes were abstracted from the electronic medical record. Paper records were reviewed if the electronic record had insufficient information. Disease progression was determined by using patient diagnostic imaging and radiology reports and physician notes. Local and regional failure were defined according to initial extent of disease. A local failure was defined as a failure at the primary site or attached lymph nodes if the two masses were readily indistinguishable. Regional failures were defined as discontiguous nodal failures within a regional draining nodal basin.

Analysis of imaging and radiation records

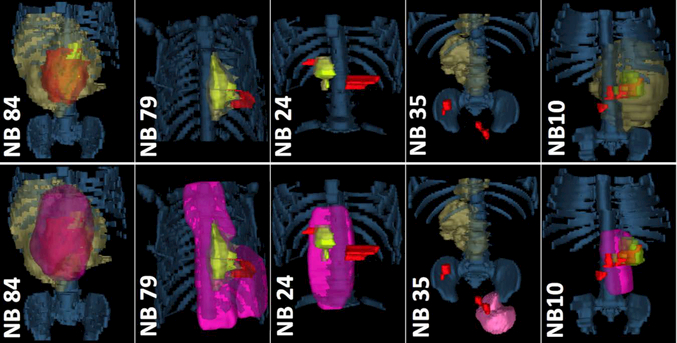

When available, CT, MRI, MIBG and/or Tc-99m MDP bone scans from diagnosis, post-induction, immediately prior to surgery, post-transplant, and treatment failure were co-registered for each patient and merged with the patient’s radiotherapy treatment plan by using MIM (v6.7.6, MIM Software Inc.). Disease volume co-incidence and extent of disease were rendered in 3 dimensions for anatomic review to better understand local-regional spread and the use of radiotherapy at salvage (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Patterns of treatment failure in patients with HRNB. Sufficient volumetric imaging was available for a proportion of patients to enable delineation of disease volumes during therapy and at failure in relation to initial and salvage RT dose. Top: Disease Volumes. Bottom: RT-Plan Overlay. Legend: Bone = Blue Denim; GTV at Diagnosis = Dark Yellow; GTV post-induction/pre-Surgery = lime green; GTV failure = red; RT dose = Pink.

Statistical methods

All data were stored in institutional databases and extracted for management in Excel 2013 (v15.0.4963.1000, Microsoft Corporation). Nonparametric descriptive measures of central tendency were used to describe patient, disease, and treatment characteristics. All time-to-event calculations were described by using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Time to progression was defined as the time from first failure to any cancer-related event or death. Time to death was defined as the time from first failure to death. SAS (v9.3, Cary, NC) and R studio (1.1.383) were used for all statistical procedures.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age of patients at diagnosis was 34 months (range, 16 months - 16 years). Two patients were classified as International Neuroblastoma Staging System stage 3 and the remaining 18 were classified as stage 4 at diagnosis. Eight of the ten patients with available MYCN amplification data did not have amplification of the oncogene. Twelve patients had adrenal primary sites; 6 had abdominopelvic primary sites, and 2 had thoracic primary sites.

Table 1.

Case Summaries

| Patient | Age at Dx (mo) |

1o Site | Stage | Shimada | MYCN | Initial Trial |

Adj RT Dose (Gy) |

Extent of 1st Failure |

Initial Salvage Therapy | Subsequent Salvage Tx | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemo | Radiotherapy(Site) in Gy | Surg | Chemo | RT | Surg | ||||||||||

| NB50 | 16 | Abd/P | 3 | F | - | NB977 | - | R | - | 36 (Para-aortic) | GTR | No Subsequent Failures | AWOD | ||

| NB51 | 52 | Adr | 4 | - | A* | NB977 | - | R | ICE | - | GTR | Unk | Unk | Unk | DOD |

| NB52 | 33 | Abd/P | 4 | - | - | NB977 | - | R | NB97 Induction | - | GTR | Yes | Yes | Yes | DOT |

| NB74 | 202 | Thorax | 4 | - | - | NB977 | - | L | - | - | - | No Subsequent Failures | DOD | ||

| NB85 | 29 | Adr | 4 | - | - | NB977 | None* | L, R | Irin/Cyclo | 36 | - | No Subsequent Failures | DOD | ||

| NB87 | 23 | Abd/P | 4 | - | - | NB977 | - | L, D | ICE,Topo, PO Irin | 36 (Celiac Axis) | - | No Subsequent Failures | DOD | ||

| NB86 | 18 | Adr | 3 | - | - | NB977 | - | R, D | Cyclo/Etop | 36 (Abdomen) | - | Yes | - | - | DOD |

| NB24 | 60 | Adr | 4 | - | - | NB977 | - | R, D | ICE, 13-cis RA | 24 (R Neck & Abd) | - | Yes | Yes | - | DOD |

| NB80 | 45 | Adr | 4 | - | N | NB977 | - | L, R, D | ICE/Topo | - | - | Yes | Yes | - | AWOD |

| NB88 | 34 | Adr | 4 | U | A | NB977 | - | L, R | ICE/Topo, 13-cis RA | 23.4 (Abdomen) | - | Yes | No | Yes | DOD |

| NB79 | 30 | Thorax | 4 | F | N | NB977 | - | L, R | DX8951f, Irin, MIBG, Etop/Topo |

27 (Thorax) | - | No Subsequent Failures | AWOD | ||

| NB84 | 69 | Adr | 4 | - | N | NB977 | 30 | L, R | 13 Cis-RA | - | - | Yes | - | - | DOT |

| NB41 | 40 | Abd/P | 4 | U | N | NB20059 | Yes | L, D | CAE | 18 (Mediastinum) | - | No Subsequent Failures | DOD | ||

| NB26 | 33 | Adr | 4 | U | N | NB20059 | None* | L, R, D | ICE | - | - | - | - | - | DOD |

| NB45 | 63 | Abd/P | 4 | - | N | NB20059 | None* | L, R, D | ICE, Vincr/Cyclo/Topo, TMZ |

- | - | Yes | Yes | - | DOD |

| NB1 | 30 | Adr | 4 | - | - | NB20059 | Yes | L, R, D | CAE + Cis/Etop | - | - | - | - | - | DOD |

| NB35 | 59 | Adr | 4 | - | N | NB20059 | 23.4 | R | GD2NK | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | AWD |

| NB 3 | 44 | Abd/P | 4 | - | A | NB20085 | None* | L, R, D | CAE | - | - | No Subsequent Failures | DOD | ||

| NB10 | 23 | Adr | 4 | U | A | NB20128 | 23.4 | L | Vincr/Irin/TMZ | 30 (L Renal Bed)** | GTR | No Subsequent Failures | AWOD | ||

| NB82 | 48 | Adr | 4 | - | N | NB977 | - | L, D | ABT-751 | 21 (L Femur, L Renal bed, R Sup Abd, Post 6th Rib, Sacrum) |

- | - | Yes | - | AWOD |

Abbreviations: Dx = Diagnosis, Abd = Abdomen, P = Pelvis, Adr = Adrenal, U/F = Unfavorable, N/A= Not/Amplified, RT = Radiotherapy, Unk = Unknown, L = Local-only Failure, R = Regional-only Failure, (L, R) = Local-Regional Failure, (L, D) = Local Failure with concurrent Distant Failure, (R, D) = Regional Failure with concurrent Distant Failure, Irin = Irinotecan, Cyclo = Cyclophosphamide, ICE = Ifosfamide, Carboplatin, Etoposide, Etop = Etoposide, Cis RA = Retinoic Acid, Topo = Topotecan, MIBG = 131I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine, CAE = Cyclo/Adriamycin/Etoposide, Vincr = Vincristine, TMZ = Temozolomide, GD2NK = anti-GD2 Antibody & NK-cell therapy, ABT-751 = Oral Antimitotic Sulfonamide Therapy, DX8951f = Exatecan Mesylate. 13-cis RA= Isotretinoin, Sup = Superior, Post = Posterior, GTR = Gross Tumor Resection, AWOD = Alive without Disease, DOD = Died of Disease, DOT = Died of Treatment, AWD = Alive with Disease

No Prior Planned RT due to Progression of Disease

=Repeat radiotherapy.

Initial treatment at diagnosis

Initial treatment at diagnosis comprised a combination of induction chemotherapy, surgery, radiation therapy, and myeloablative chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support. Frontline therapy was per protocol as indicated in Table 1. Details regarding the extent of initial therapy have been previously described5–10. In brief, induction chemotherapy was administered to reduce bulk tumor volume. Surgical timing for primary tumor resection was varied but was completed at any time from diagnosis to immediately following induction chemotherapy. Thirteen of the patients in the study had a gross or near total resection at diagnosis, while seven had a subtotal resection at diagnosis. Following chemotherapy and surgery, patients received an intensification course of high-dose chemotherapy and peripheral blood stem cell support. The intensity of systemic therapy during induction and consolidation varied during the course of therapy and the trial directed cumulative doses and dose intensities of therapy during each phase are shown in Supplementary Table S1 and S2. While the dose intensity of agents such as cyclophosphamide was 194 mg/m2/week in NB97, the projected cumulative dose in NB2012 was three fold higher (689 mg/m2) than NB97. External-beam radiotherapy was administered to the post-induction chemotherapy, preoperative tumor volume in patients treated with frontline radiotherapy (NB1, NB10, NB35, NB41, NB84, Figure 1) with initial total RT dose of 30.6 (n=1) or 23.4 Gy (n=2) or unknown/not restorable (n = 2). Extended patient timelines detailing the initial disease course are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

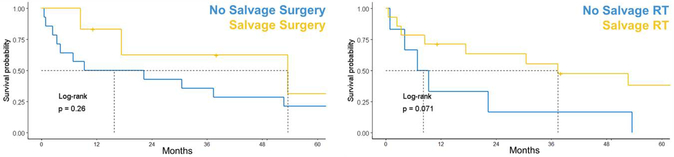

FIGURE 1.

Sankey Diagram Depicting Pertinent Management of Patients who experienced Local-Regional Failure. Data were extracted from the electronic medical record of 20 patients [median age, 34 mo, range (16mo-16yrs)] with high-risk neuroblastoma who experienced recurrence on prospective trials from 1997–2013. Initial therapy was induction chemotherapy, surgery, and myeloablative chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support; 14 patients underwent 19 salvage radiotherapy courses to either the primary or metastatic sites. Surgery was used selectively in 4 patients had either local-only or regional-only failure at initial recurrence. LF = Local Failure, RF = Regional Failure, DF = Distant Failure, RT = Radiotherapy, Surg = Surgery, Chemo = Chemotherapy, AWOD = Alive Without Disease, DOD = Died of Disease, DOT = Died of Treatment. AWD = alive with disease.

Extent of recurrence

The extent of disease at relapse was variable. Extent of disease at failure was as follows; 2 local only (LF), 4 regional only (RF), 4 local-regional (LRF), 5 combined local or regional and distant (LRDF), and 5 combined local, regional and distant failure (LRDFC) (See Table 1, Figure 1).

Salvage therapy

Treatment at failure consisted of varying combinations of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, and transplant (See Figure 1). The most common recurrence site was within the abdomen along the para-aortic lymph node chain (3 of 20 patients) (See Table 1). Surgery was used selectively in four patients having local-only or regional-only failure at initial recurrence. Eighteen patients received one or more chemotherapy regimens following relapse (see Table 1). Most patients in our series were managed with ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) at relapse, although some were treated with IT. The remaining patients in our study were managed with more conventional salvage therapy regimens (Cyclophosphamide / Topotecan). Four patients were treated on prospective trials at relapse 11–14. Anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody was used at salvage in one patient15. One patient obtained salvage with 131I-MIBG therapy at an outside hospital. Fourteen patients in our final cohort who were irradiated as part of their salvage treatment strategy underwent a combined total of 19 salvage RT courses to the primary and/or metastatic sites. Only 1 patient received repeat radiotherapy to an initially irradiated site of disease for an infield relapse (See Figure 1)this patient experienced minimal toxicity (< grade 3) and is alive without disease (NB10, Table 1). Extended patient timelines detailing the salvage therapy course are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Outcomes

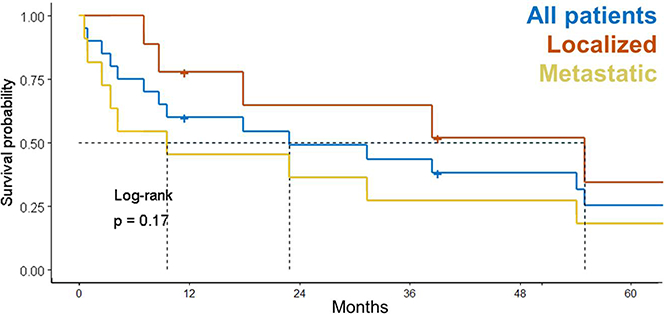

After a median follow-up time of 13 years (range, 0.9–25.2 years), 6 patients with LRF patients were alive following salvage therapy (See Figure 1, Table 1). Two patients died of complications related to therapy including complications related to prolonged myelosuppression. The median duration of chemotherapy prior to subsequent progression was 11 months (95% CI, 4.8–15 months). Among the 10 patients managed at relapse with combinations of RT+/−surgery, +/−chemotherapy, four were alive without disease at last follow-up. As shown in Figure 2, median overall survival (OS) was 4.6 years (95% CI, 0.6 – not reached) after LRF and 0.6 years (95% CI, 0.05–2.6 years) after LRF with distant failure (DF) (p=0.03).

FIGURE 2.

Survival probability after HRNB recurrence stratified by extent of relapse. Median follow-up: 13 y (range, 0.9–25.2 y). At last follow-up, 6 patients (1 local-only, 2 regional-only, 1 local-regional failure, 1 local-only with concurrent distant & 1 local-regional failure with concurrent distant failure) were alive following salvage therapy. Survival in patients treated with RT at LRF had survival comparable to that of those who received RT during initial therapy. The time to LRF was 8.7 mo in those who received planned adjuvant RT after autologous stem cell transplant and 14.6 mo in those who received no RT after transplant.

Prognostic factors at relapse

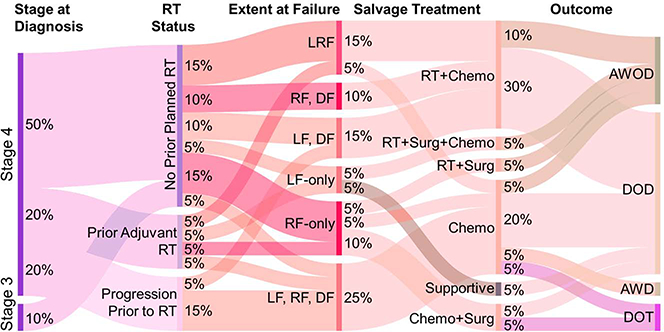

OS in the presence cohort of 20 patients who were previously unirradiated treated with RT at LRF had survival comparable to patients with LRF who received RT during initial therapy but did not receive radiotherapy at salvage (p=0.35). Early time to failure (<12 months from diagnosis) showed a non-significant trend toward reduced survival relative to patients who experienced treatment failure >12 months from diagnosis (p=0.13). Initial stage, Shimada status, and MYCN status did not significantly impact survival from first failure (p=0.45, p=0.11, and p=0.3 respectively). More intensive initial therapeutic regimens (NB2005, NB2008, NB2012) displayed a trend toward shorter time to death following first relapse relative to those treated on older trials (NB97) with a median OS 9.58 mo (95% CI 4.27-NR) vs median OS 31.18 mo (95% CI 8.68-NR) respectively (p=0.38) (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S1, S2, and S3). Salvage RT reduced the hazard for subsequent failure events (HR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.9; p=0.04) when used as a time-dependent covariate but failed to reach significance when evaluating the impact on overall survival (median OS 38 (95CI 17.8-NR) in those receiving salvage radiotherapy vs. 8.3 (4.3-NR) p=0.071 in those managed without salvage radiotherapy). While patients who underwent resection tended to have longer median OS (4.6 vs. 1.3 years, p = 0.2) relative to patients treated only with chemotherapy, this failed to reach statistical significance (See Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Overall survival (OS) of patients with HRNB after 1st treatment failure. Patients who underwent resection tended to have improved OS (4.6 vs. 1.3yrs, p = 0.26) compared to those treated only with chemotherapy. Salvage radiotherapy (RT) reduced the hazard for subsequent failure (HR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.9, p=0.04) and there was a trend toward improved OS in those who received salvage radiotherapy at any time.

Review of Initial and Failure Treatment Volume in Relation to Radiotherapy Plan

Volumetric imaging documenting local and/or regional failure was available in five of twenty patients (See Figure 4) while fifteen patients imaging data were stored as serialized MRI, CT or bone scan axial images on a film sheet or were unavailable. Radiotherapy target volumes encompassed disease at recurrence in three of the four cases shown while patient NB35 experienced a late out of field pelvic nodal relapse.

DISCUSSION

Use of local therapies at salvage in HRNB has been limited given the propensity for multifocal metastatic disease and unclear data on its utility. We review outcomes of twenty patients with local and or regional relapse managed with varied local control strategies and document successful salvage and durable disease control in a limited subgroup of patients with local/regional only relapse.

Prognostic features at relapse in HRNB

Prognostic features at the time of diagnosis in patients with HRNB are well characterized; however, few studies have reviewed prognostic features at the time of relapse. Of the studies that have addressed overall survival after relapse, evidence has suggested that the time to first relapse, stage, MYCN amplification, mIBG scan scoring, and age at diagnosis are prognostic factors that impact OS.16 While subset analyses are difficult in our limited cohort, we did observe an impact of the extent of disease at relapse (Figure 2). We also observed a trend towards improved overall survival from first relapse in patients who experienced relapse >12 months from diagnosis, and for patients with Shimada favorable disease (Supplementary Figure S2). A study conducted by the Children’s Oncology Group sought to determine whether time from diagnosis to first relapse was a significant predictor of OS using the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) database with over 2,000 patients who experienced first-time relapse16. The study determined that the risk of death is higher for patients whose disease relapses within 18 months after diagnosis, for those who are older at diagnosis, and for those with MYCN amplification. Thirteen of twenty patients in our cohort were initially treated on NB97 which has reduced intensity and cumulative doses of oxazophosphorine equivalents, adriamycin, and topotecan. The patients treated with more modern intensive induction and consolidation regimens (NB2005, NB2008, and NB2012) exhibited a trend toward reduced time to death from first relapse (Supplementary Figure S2). As a result, initial therapy intensity should be considered when weighing the potential utility of local therapy at salvage.

Impact of local treatment modalities at relapse

Prior reports have considered the use of alternative radiotherapy delivery strategies at salvage in both previously irradiated and non-irradiated patients 3,4,17. While subset analyses are difficult in our limited cohort, we did observe an impact of measures used for local control of the locoregional relapse (Figure 3). Other groups have observed similar findings regarding the use of radiotherapy at recurrence. One study investigated the possible role of intraoperative radiation therapy after re-resection of locally recurrent or refractory neuroblastoma3. This study found that intraoperative radiation therapy after prior external beam radiotherapy had an acceptable toxicity profile, a favorable local control rate of 55 % at 2 years, and possibly a prolonged overall survival in well-selected cases.3 An additional study evaluated the use of another form of external beam radiotherapy, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), in a child with HRNB following recurrence 4. Although SBRT effectively controlled this patient’s disease, it was not without significant toxicity.4 The report suggests that the further use of SBRT in previously irradiated children with refractory or recurrent HRNB should be investigated and approached with caution. Only one patient treated in our series had received a prior course of external beam radiotherapy and was retreated for an infield relapse. Toxicity was limited and the patient is alive without disease (NB10, Table 1).

Impact of systemic treatment modalities at relapse

The high metastatic failure rate in refractory and recurrent neuroblastoma has led investigators to evaluate novel combinations of systemic therapy in the salvage setting18. Some data suggest that patients with refractory disease might have better response rates with 131I-MIBG therapy than do patients with relapsing disease.19 131I-MIBG therapy is currently moved to the forefront of initial therapy in treatment naïve patients in the COG ANBL1531 trial. Only one patient in our series was managed with 131I-MIBG therapy at relapse and as a result limited conclusions can be drawn. More recently, 5-day irinotecan plus temozolomide (IT) has been shown to have favorable response rates, minimal organ toxicity, and limited immunosuppression and as a result has become the backbone for addition of other agents.20‘15,21 Most patients in our series were managed with ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) at relapse, although some were treated with IT. The use of IT in combination with dinutuximab, an anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody, is now a favored regimen given the recent (March 2015) FDA approval for primary therapy.15 Only one patient in our series was managed with anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody at relapse and is alive to present with stable disease. Others were not considered for this treatment regimen given that most were treated prior to the FDA approval of dinituximab. The remaining patients in our study were managed with more conventional salvage therapy regimens (Cyclophosphamide / Topotecan), now considered an inferior salvage chemotherapy regimen, but had prolonged survival at the time of relapse relative to more recent studies15. It remains unclear whether the intensity and cumulative doses of initial systemic therapy had a substantial impact on the prognosis at relapse, although patients managed on reduced intensity trials like NB97 did show improved survival from the time of relapse (Supplementary Figure S2). It is possible that the incorporation of more effective second line therapy (IT +/− Dinituximab) at the time of first salvage in patients would lead to improved overall survival relative to the regimens selected for this analysis to those managed with more recent intensive systemic therapy regimens which incorporate the use of tandem transplantation 22. Prior studies have reported on the relevance of systemic therapy intensity to treatment outcomes and therapeutic response in the upfront setting. While Pearson et al noted improved event free survival in patients managed for dose intense induction chemotherapy relative to standard induction chemotherapy, no gain in overall survival was reported23. No prior reports have investigated the impact of initial therapy intensity on prognosis at first relapse and as such it remains unclear if there is a trade-off between initial systemic therapy intensity and subsequent salvage rate with regards to prognosis24,25.

Conclusion

Further investigation into maximizing the efficacy of the current modalities used to treat relapsing HRNB should continue to improve the current low survival rates. Our study demonstrates the potential efficacy of local control strategies at the time of local recurrence in HRNB patients without concurrent distant failure. Local therapy combined with systemic therapy in well selected recurrent HRNB patients with delayed relapse (>12 months from diagnosis), and absence of systemic relapse may experience improved clinical outcomes relative to patients who are managed with more intensive induction and consolidation regimens at diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1. Extended Natural History Diagram

Supplementary Figure S2. Survival from First Relapse in Patient with HRNB Treated on Prospective Trials stratified by Failure Timing (top left), Initial Stage (top right), Initial Shimada (middle left), Initial MYCN Status (middle right), and Initial Treatment (bottom left).

Supplementary Table S1. Chemotherapy Dose, and Schedule for HRNB patients treated on the cited trials.

Supplementary Table S2 - Chemotherapy Dose Intensity (mg/m2/week*): Comparison of Induction Regimens. ^

Supplementary Table S3 - Chemotherapy Cumulative Dose: Comparison of Induction Regimens. ^

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Roletta Ammons for helping to assemble the figures for this manuscript.

Grant: Supported in part by grant 5R25CA23944 from the National Cancer Institute (APD, BAM), Cancer Center Grant: NCI 2P30 CA021765 and American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Abbreviation key:

- Abd*

Abdomen

- ABT-751*

Oral Antimitotic Sulfonamide Therapy

- Adr*

Adrenal

- AWD*

Alive with Disease

- AWOD*

Alive without Disease

- CAE*

Cyclophosphamide/Adriamycin/Etoposide

- Cis RA*

Retinoic Acid

- Cyclo*

Cyclophosphamide

- DOD*

Died of Disease

- DOT*

Died of Treatment

- Dx*

Diagnosis

- Etop*

Etoposide

- GD2NK*

Anti-GD2 Antibody & Natural Killer Cell Therapy

- GTR*

Gross Tumor Resection

- HRNB

High-risk Neuroblastoma

- ICE*

Ifosfamide, Carboplatin, Etoposide

- INRG

International Neuroblastoma Risk Group

- Irin*

Irinotecan

- IT

Irinotecan plus Temozolomide

- L*

Local-only Failure

- L D*

Local failure with concurrent Distant failure

- LR*

Local-regional failure

- LRD

Local, Regional, and Distant failure

- MIBG

Metaiodobenzylguanidine

- N/A*

Not/Amplified

- NB

Neuroblastoma

- OS

Overall Survival

- P*

Pelvis

- Post*

Posterior

- R*

Regional-only Failure

- R D*

Regional Failure with concurrent Distant Failure

- RT

Radiotherapy

- SBRT

Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy

- SJCRH

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

- Sup*

Superior

- TMZ*

Temozolomide

- TOPO

Topotecan

- TOPO/CTX

Topotecan plus Cyclophosphamide

- U/F*

Unfavorable

- Unk*

Unknown

- Vincr*

Vincristine

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Irwin MS, Park JR. Neuroblastoma: paradigm for precision medicine. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(1):225–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leavey PJ, Odom LF, Poole M, McNeely L, Tyson RW, Haase GM. Intra-operative radiation therapy in pediatric neuroblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28(6):424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rich BS, McEvoy MP, LaQuaglia MP, Wolden SL. Local control, survival, and operative morbidity and mortality after re-resection, and intraoperative radiation therapy for recurrent or persistent primary high-risk neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(1):97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taunk NK, Kushner B, Ibanez K, Wolden SL. Short-Interval Retreatment With Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) for Pediatric Neuroblastoma Resulting in Severe Myositis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(4):731–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuroblastoma Protocol 2008: Therapy for Children With Advanced Stage High Risk Neuroblastoma. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00808899.

- 6.COG-P9641 - Surgery in Treating Children With Neuroblastoma. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00003119.

- 7.NB97 - Therapy for Children With Advanced Stage High Risk Neuroblastoma. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00186849.

- 8.NB2012 - Therapy for Children With Advanced Stage Neuroblastoma. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01857934.

- 9.NB2005 - Therapy for Children With Neuroblastoma. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00135135.

- 10.Santana VM, Furman WL, Billups CA, et al. Improved response in high-risk neuroblastoma with protracted topotecan administration using a pharmacokinetically guided dosing approach. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4039–4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ABT-751 in Treating Young Patients With Refractory Solid Tumors. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00036959.

- 12.Combination Chemotherapy, Monoclonal Antibody, and Natural Killer Cells in Treating Young Patients With Recurrent or Refractory Neuroblastoma. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01576692.

- 13.DX-8951f in Treating Children With Advanced Solid Tumors or Lymphomas. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00004212.

- 14.Iobenguane I-131 or Crizotinib and Standard Therapy in Treating Younger Patients With Newly-Diagnosed High-Risk Neuroblastoma or Ganglioneuroblastoma. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03126916.

- 15.Mody R, Naranjo A, Van Ryn C, et al. Irinotecan-temozolomide with temsirolimus or dinutuximab in children with refractory or relapsed neuroblastoma (COG ANBL1221): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2017;18(7):946–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.London WB, Castel V, Monclair T, et al. Clinical and biologic features predictive of survival after relapse of neuroblastoma: a report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group project. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(24):3286–3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthay KK, Yanik G, Messina J, et al. Phase II study on the effect of disease sites, age, and prior therapy on response to iodine-131-metaiodobenzylguanidine therapy in refractory neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):1054–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.London WB, Frantz CN, Campbell LA, et al. Phase II randomized comparison of topotecan plus cyclophosphamide versus topotecan alone in children with recurrent or refractory neuroblastoma: a Children’s Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(24):3808–3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou MJ, Doral MY, DuBois SG, Villablanca JG, Yanik GA, Matthay KK. Different outcomes for relapsed versus refractory neuroblastoma after therapy with (131)I-metaiodobenzylguanidine ((131)I-MIBG). Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(16):2465–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kushner BH, Kramer K, Modak S, Cheung NK. Irinotecan plus temozolomide for relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5271–5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modak S, Kushner BH, Basu E, Roberts SS, Cheung NK. Combination of bevacizumab, irinotecan, and temozolomide for refractory or relapsed neuroblastoma: Results of a phase II study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George RE, Li S, Medeiros-Nancarrow C, et al. High-risk neuroblastoma treated with tandem autologous peripheral-blood stem cell-supported transplantation: long-term survival update. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2891–2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearson AD, Pinkerton CR, Lewis IJ, et al. High-dose rapid and standard induction chemotherapy for patients aged over 1 year with stage 4 neuroblastoma: a randomised trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2008;9(3):247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung NV, Heller G. Chemotherapy dose intensity correlates strongly with response, median survival, and median progression-free survival in metastatic neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(6):1050–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peinemann F, Tushabe DA, van Dalen EC, Berthold F. Rapid COJEC versus standard induction therapies for high-risk neuroblastoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(5):CD010774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Extended Natural History Diagram

Supplementary Figure S2. Survival from First Relapse in Patient with HRNB Treated on Prospective Trials stratified by Failure Timing (top left), Initial Stage (top right), Initial Shimada (middle left), Initial MYCN Status (middle right), and Initial Treatment (bottom left).

Supplementary Table S1. Chemotherapy Dose, and Schedule for HRNB patients treated on the cited trials.

Supplementary Table S2 - Chemotherapy Dose Intensity (mg/m2/week*): Comparison of Induction Regimens. ^

Supplementary Table S3 - Chemotherapy Cumulative Dose: Comparison of Induction Regimens. ^