Abstract

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) has been identified as a powerful independent negative predictor of cardiovascular disease. The beneficial effect of HDL is largely attributable to its key role in reverse cholesterol transport, whereby excess cholesterol in the peripheral tissues is transported to the liver, reducing the atherosclerotic burden. However, mounting evidence indicates that HDL also has pleiotropic properties, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and vasodilatory properties, which may contribute in reducing the incidence of heart failure. Actually, previous data from clinical and experimental studies have suggested that HDL exerts cardioprotective effects irrespective of the presence/absence of coronary artery disease. This review summarizes the currently available evidence regarding beneficial effects of HDL on the heart beyond its anti-atherogenic property. Understanding the mechanisms of cardiac protection by HDL will provide new insight into the underlying mechanism and therapeutic strategy for heart failure.

Keywords: High-density lipoprotein, Cardioprotective effect, Heart failure, Fatty acid, Endothelial lipase, mTOR signal

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is the terminal state of all heart diseases and is the leading cause of mortality worldwide. According to the American Heart Association, there are approximately 550,000 new patients with HF each year1). Although considerable advances have been made in our understanding of HF, the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and financial burden of the disease continue to steadily increase in the aging population. Therefore, elucidating modifiable risk factors for HF will aid in identifying prevention strategies or developing novel therapeutic approaches.

Numerous studies have established an inverse relationship between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in humans2–5); low HDL-C is considered to be one of the most important coronary risk factors6). This beneficial effect of HDL on the cardiovascular system is largely attributable to its key role in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), whereby excessive cholesterol in the peripheral tissues is transported to the liver, reducing the atherosclerotic burden. However, a large amount of evidence has revealed that HDL has many anti-atherosclerotic properties represented by anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, anti-thrombotic, anti-apoptotic, and vasodilatory properties, and these vasoprotective effects seem to be independent of RCT activity7, 8). Hence, it may be reasonable to consider that such properties of circulating HDL do not only protect the coronary vessel wall against atherosclerosis but also exert direct beneficial effects on the myocardium, leading to reduction of the incidence of myocardial diseases, including HF.

It has been well known that cigarette smoking has a negative impact on RCT and reduces circulating HDL-C levels, which is involved in the progression of cardiovascular disease9, 10). Conversely, several studies have suggested that HDL exerts atherosclerosis-independent cardioprotective effects on the pathological status. Horio et al. investigated the influence of serum lipids on LV functions in patients with essential hypertension and found that low HDL-C level is an independent predictor of LV mass and LV diastolic dysfunction11). An independent association between low HDL-C level and subclinical LV systolic dysfunction has been observed in patients with not only stable angina but also normal coronary angiogram12), and Kerola et al. suggested that HDL is superior to B-type natriuretic peptide as a marker of systolic cardiac dysfunction in an elderly general population13). Moreover, NIPPON DATA90, a large cohort study of cardiovascular disease in Japan, addressed the association between HDL-C levels and HF incidence; serum HDL-C levels tended to show an inverse association with HF mortality with borderline significance and a significant inverse association with all-cause mortality14). In line with this observation, Vredevoe et al. reported that HDL-C is a predictor of mortality in patients with idiopathic HF15). Taken together, HDL exerts direct cardioprotective effects independent of the atheroprotective property, which possibly influences LV function and HF incidence. In the present review, we summarize currently available evidence regarding direct beneficial effects of HDL on the heart beyond the anti-atherogenic property and discuss underlying mechanisms that have been implicated.

1. HDL Provides Fatty Acids as Energy Substrates for the Myocardium

Vast amounts of energy are required for fueling the continuous pumping action of the heart. Under normal circumstances, nearly 70% of the energy substrate used for myocardial contraction is derived from fatty acid (FA) oxidation and the remainder comes from glucose, lactate, and ketone body oxidation16). Thus, FAs are considered to be the major energy source for the myocardium, which are delivered to cardiomyocytes in three ways: 1) FAs are produced in the local capillary bed by hydrolysis of triglycerides (TGs) contained in circulating TG-rich lipoproteins (TRL), such as chylomicrons and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), via actions of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), 2) FAs are produced by hydrolysis of intracellular TG storages, and 3) FAs are derived from circulating free FAs, referred to as non-esterified FA (NEFA), complexed with serum albumin17). Moreover, phospholipids might be one of the resources of FAs, whereas metabolic regulation in the heart remains to be fully elucidated. In particular, LPL-mediated lipolysis of chylomicrons and VLDL significantly contributes to cardiac energy supply18, 19); therefore, LPL plays a central role in energy homeostasis in the heart17). LPL is synthesized in cardiomyocytes and then migrates to the luminal surface of vascular endothelial cells where hydrolysis of TRL takes place20). In contrast to esterified FAs derived from TRL, NEFA availability is limited because of its low solubility and high toxicity. Myocardium uptakes NEFA as an energy source by passive diffusion and several transporters, such as FA-binding protein, FA translocase (FAT/CD36), and FA transport protein16). Hauton et al. investigated myocardial lipid substrate preference by comparing utilization of NEFA, VLDL-TGs, and CM-TGs in rat-isolated perfused hearts and concluded that myocardial utilization of NEFA and CM-TGs is higher than that of VLDL-TGs21). Besides LPL-mediated lipolysis, there is an alternative mechanism by which TRL is assimilated into the heart. The VLDL receptor is a member of the LDL receptor gene family, which has high expression in the heart, and is associated with the uptake of apolipoprotein E-containing lipoproteins22, 23). Although cardiomyocytes also express scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), a receptor related to the uptake of cholesterol from HDL24, 25), it remains unknown whether HDL particles are incorporated into the heart via SR-BI.

Cardiomyocytes possess endothelial lipase (EL), which is another member of the TG lipase family. Although basal expression of EL in cardiomyocytes is very low, its expression level is upregulated under pathological conditions, including inflammation, mechanical, and oxidative stress26). EL is considered to bind to cell surface proteoglycans where it can directly interact with lipoproteins27–29). EL primarily has phospholipase activity and relatively less TG lipase activity and exhibits preferential substrate specificity for phospholipids on HDL29). Therefore, EL has the potential ability to release FAs from not only TGs contained in TRL but also phospholipids contained in HDL. However, relative contribution of EL-mediated HDL hydrolysis and TRL lipolysis in FA supply to the myocardium needs to be determined in the future.

A large amount of evidence suggests that cardiac energy metabolism is severely impaired in the failing heart30, 31). Namely, the failing heart is commonly described as an energy-starved engine that has run out of fuel31). During development of HF, the predominant myocardial energy substrate switches from FAs to glucose because glucose oxidation allows the heart to produce intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using less oxygen than that needed for FA oxidation31–33). However, compromised cardiac energy metabolism may cause and worsen myocardial dysfunction. Total β-oxidation in the heart is increased by 40% in response to acute energy demand34) and increased glucose oxidation alone is reported to be insufficient to meet the cardiac energy requirement under stress conditions33, 35). Augustus et al. reported that heart-specific LPL knockout (hLpL0) mice were susceptible to HF because of loss of LPL-mediated TG lipolysis in spite of increased glucose oxidation35). They showed that hearts of hLpL0 mice that underwent abdominal aortic constriction were unable to adapt acutely to pressure overload, thereby, all banded hLpL0 mice died within 48 h, whereas all banded wild-type mice continued to thrive. Similarly, the lack of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1α), a regulator of numerous genes involved in FA import and oxidation, accelerates pressure overload-induced HF induced by transverse aortic constriction36). These findings indicate that FAs are indispensable energy substrates even in the failing myocardium.

Kratky et al. observed that EL compensates for free FA uptake in LPL-deficient mouse adipose tissue, which indicates that EL provides an alternative pathway for FA uptake when the action of LPL is insufficient37). Expression of EL in the cardiac tissues is increased in the early phase of pressure overload-induced HF, whereas expression of LPL is significantly decreased26). Subsequently, EL deficiency worsens pressure overload-induced HF due to the attenuated energy production from FA oxidation, which suggests that EL-mediated FA supply from HDL is important for the myocardium in the setting of increased energy demand or insufficient LPL action. In addition, various FAs act as ligands for PPARα38), which regulates mitochondrial FA oxidation-related genes. Ahmed et al. revealed that EL-mediated hydrolysis of HDL activates PPARα and subsequently upregulates the expression of acyl-CoA-oxidase, a well-established FA oxidation-related gene39). In line with this finding, incubation of EL-overexpressing cardiomyocytes with HDL augmented the expression of FA oxidation-related genes carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 and medium-chain acyl CoA dehydrogenase which was accompanied by an increase in intracellular ATP26). From these findings, it is considered that EL-mediated FA supply from HDL not only increases energy substrates for the myocardium but also upregulates the expression of PPARα-mediated FA oxidation-related genes, thereby preserving FA utilization in the failing heart.

2. HDL Protects Cardiomyocytes Against Oxidative Stress

There is a well-established relationship between myocardial reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and left ventricular contractile dysfunction, which results in HF40, 41). ROS is generated in the ischemic myocardium, particularly after reperfusion, leading to cell death42). One of the most important properties of HDL is its ability to reduce oxidative stress caused by excessive ROS formation7, 8). There is evidence that HDL inhibits NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent ROS generation in vascular smooth muscle cells and isolated aortas43). With regard to the myocardium, in an ex vivo model of ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, Marchesi M et al. showed that synthetic HDL, recombinant apo A-I Milano complexed with 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine, reduced cardiac muscle lipid hydroperoxide levels by 46% via its antioxidant potential, thereby attenuating post-ischemic LV dysfunction44).

We recently reported that HDL treatment improved cardiomyocyte viability under oxidative stress through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway45). mTOR belongs to the PI3K-related kinase family and critically regulates protein synthesis, cell survival, growth, and proliferation46). In addition, several studies have identified mTOR as an important regulator of cardiac adaptation because its overexpression is protective in pressure-overloaded mouse hearts47, 48) and its conditional knockout in murine heart causes cardiac dysfunction49). We demonstrated that HDL activated downstream effectors of mTOR signaling, which played anti-apoptotic roles under oxidative stress, may contribute to cardioprotection45).

3. HDL Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effects in the Myocardium

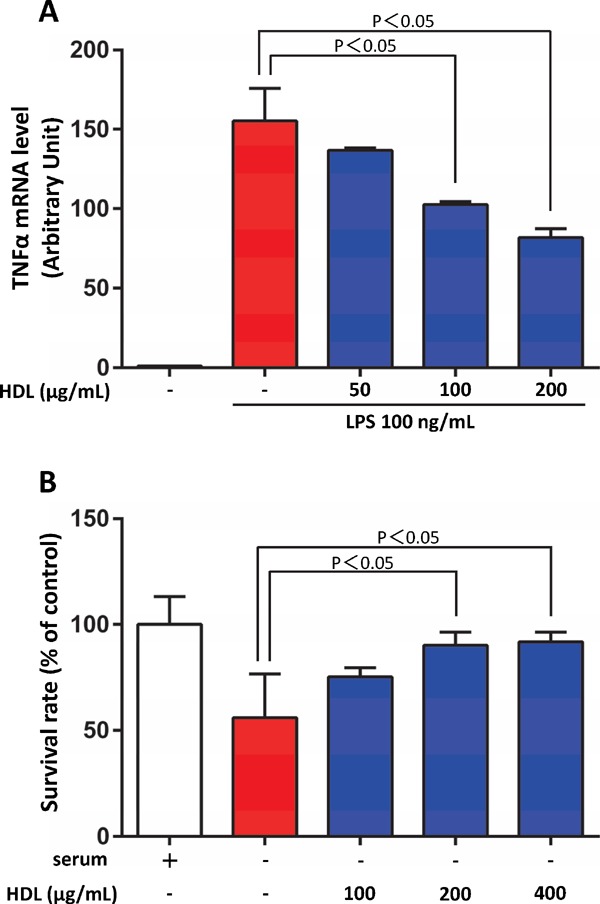

HF is known as a disorder characterized in part by immune activation and inflammation50). Niebauer et al. showed that plasma bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) levels were increased in patients with HF and peripheral edema probably because venous congestion leads to altered gut permeability for endotoxin and translocation of the endotoxin into the systemic circulation51). Because endotoxin is a very strong stimulator for the release of inflammatory cytokines from circulating immune competent cells52), it may cause substantial immune activation in patients with HF. Conversely, lipoproteins have been shown to bind and inactivate endotoxin in proportion to their cholesterol content53). It has been postulated that low plasma cholesterol levels, a surrogate for the totality of lipoproteins, is related to impaired survival in patients with idiopathic HF15). Similarly, Rauchhaus M et al. proposed that high plasma cholesterol levels in chronic HF are beneficial on the basis of the capacity of circulating cholesterol-rich lipoproteins to bind and inactivate endotoxin52). Notably, Ulevitch et al. reported that HDL suppressed the buoyant density of LPS in human serum more effectively than LDL or VLDL54). Similar to this finding, it was reported that the phospholipid bilayer of the HDL surface could bind to lipid-A, an anchor protein of LPS, to neutralize the activity of LPS55). In fact, HDL inhibits LPS-induced expression of cytokines in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1A). In addition, infusion of reconstituted HDL reduces cytokinemia and improves clinical outcome in rabbit gram-negative bacteremia models56). Furthermore, targeted deletion of EL results in an increase in phospholipid and cholesterol content in HDL particles and thereby improves the survival rate of endotoxin shock in a mouse model of LPS-induced septic shock57). These findings indicate that HDL can diminish detrimental effects of endotoxemia in vivo. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that HDL protects against HF by attenuating the action of endotoxin in edematous patient with HF.

Fig. 1.

HDL protected the cardiomyocytes from cell death and inflammatory damages

A) Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated with lipopolysaccharides (LPS) for 24 h. The mRNA level of TNF-α was evaluated by real-time PCR and calibrated with that of GAPDH. HDL attenuated LPS-induced expression of TNF-α in cardiomyocytes. B) Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated in serum-depleted medium with or without HDL for 24 h, and cell viability was assessed by WST-1 assay. HDL protected the cardiomyocytes from serum starvation-induced cell death.

4. HDL Enhances Myocardial Perfusion Via Nitric Oxide-Mediated Vasodilatory Effects

There is evidence that HDL administration increases myocardial perfusion in vivo via nitric oxide (NO)-dependent mechanisms58), suggesting that HDL acts as a coronary vasodilator. HDL mediates vasodilatation via NO release59–61). Nofer et al. reported that HDL stimulates NO release in human endothelial cells and induces vasodilation in isolated aortas via intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and Akt-mediated endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation59). The vasoactive effect of HDL was mimicked by three lysophospholipids contained in HDL: sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPC), and lysosulfatide (LSF). Deficiency of the S1P3 receptor abolished vasodilatory effects of these lysophospholipids, which indicates that HDL functions as a carrier of bioactive lysophospholipids and induces NO-dependent vasodilation via S1P3 receptor. Conversely, Yuhanna et al. have shown that HDL activates eNOS via SR-BI through a process that requires apoA-I binding in endothelial cells, resulting in increased NO production60). Afterward, it was identified that apoA-I interaction with SR-BI led to Src-mediated PI3K activation and then PI3K activated Akt kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, both of which stimulate eNOS activity61). Collectively, HDL activates eNOS in endothelial cells through dual signaling pathways involved in S1P receptors and SR-BI and causes NO-mediated vasodilation. In the heart, Levkau B et al. observed that administration of human HDL enhanced incorporation of the perfusion tracer 99mTc-methoxyisobutylisonitrile into the murine heart in vivo by approximately 18%; this increase was completely abolished in mice deficient of endothelial NO synthase58). Furthermore, the stimulatory effect of HDL on myocardial perfusion was preserved in S1P3-deficient mice, which implies that SR-BI-mediated, but not S1P3-mediated, eNOS activation in endothelial cells may be mainly related to the stimulatory effect of HDL on myocardial perfusion.

5. HDL Protects Cardiomyocytes by Activating Beneficial Signal Transducers in the Heart

Among HDL constituents that mediate diverse biological effects, S1P is one of the major lipid constituents of HDL; it has gained special attention because it may be responsible for many of the pleiotropic effects of HDL. The major source of S1P is hematopoietic cells (mainly erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes), whereas HDL serves as a major carrier of extracellular S1P in the plasma62). Zhang et al. showed that HDL-associated S1P is the major determinant of the plasma S1P level and positively correlates with HDL-C and apolipoprotein A-I (apo A-I) levels63). S1P is a biologically active sphingolipid metabolite involved in numerous cell activities, including proliferation, differentiation, survival, cytoskeletal rearrangements, cell motility, immunity, and angiogenesis64, 65). These activities are mediated through binding of S1P to its cell surface G protein-coupled receptors, which comprise S1P1–565). Although the expression of S1P4 and S1P5 is limited to the immune and nervous system, S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 are widely expressed in various cell types, including cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells66). Tao et al. showed that treatment of isolated cardiomyocytes with HDL enhanced cell survival during hypoxia-reoxygenation67). They found that HDL activates prosurvival signals, MEK1/2-ERK1/2 and PI3-kinase-Akt, via S1P1 and S1P3 receptors on cardiomyocytes, respectively. Conversely, Frias et al. demonstrated that HDL and its S1P component protected cardiomyocytes against doxorubicin-induced apoptosis through the S1P2-ERK1/2-STAT3-mediated pathway68). Thelmeier et al. reported that HDL and S1P reduced the infarct size by inhibition of inflammatory neutrophil recruitment and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in a mouse model of myocardial I/R69). Cardioprotective effects were completely absent in S1P3-deficient mice and was also canceled by pharmacological eNOS inhibition, indicating that HDL- and S1P-mediated cardioprotection is dependent on S1P3-mediated pathway by NO-dependent mechanisms. They proposed that strategies designed to rapidly elevate HDL levels in general and their S1P content may improve prognosis of the myocardium against ischemia and reperfusion. In addition to S1P, the same group also reported that SPC, another HDL-associated sphingophospholipid, directly protects against myocardial I/R injury in vivo via the S1P3 receptor because of its diverse affinity to different receptor subsets70).

Morel S et al. reported that HDL or S1P induced PKC-dependent phosphorylation of connexin43 (Cx43), a major myocardial gap junction protein responsible for rapid, synchronous transmission of cardiac action potential71). They also observed that short-term treatment with HDL or S1P at the onset of reperfusion limited the infarct size induced by I/R insult, in part, by affecting Cx43 gap junction channels in cardiomyocytes. Conversely, the survivor activating factor enhancement (SAFE) pathway, a novel powerful prosurvival signaling pathway that is associated with the activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), protects against I/R injuries72). Frias MA et al. demonstrated that HDL protects against I/R injury by inhibition of mitochondrial mPTP opening, and this effect is mediated via activation of the SAFE pathway by HDL73). This result suggests that HDL influences mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes.

We found that HDL protects the cardiomyocytes from cell death (Fig. 1B). In addition, we have revealed that HDL treatment improves cardiomyocyte viability under oxidative stress and that the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway mediates these effects45). In this study, we demonstrated that HDL treatment increased phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) and BCL2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD) under oxidative stress via PI3K/mTOR. S6K is known as a downstream effector kinase of mTOR signaling and is related to anti-apoptotic signaling through maintenance of BAD phosphorylation. Shende et al. reported that mTOR-complex 1 activity was essential for preserving cardiac function. Its deletion impaired cardiac function, leading to dilated cardiomyopathy and high mortality74). Correspondingly, they showed that the mTORcomplex 2 was associated with preserving left ventricular contractile function of pressure-overloaded mouse hearts. Cardiac dysfunction due to transverse aortic constriction was more severe after ablation of rictor, a specific component of mTOR275). Thus, in terms of cardiac protection, HDL could be an important activator of mTOR signaling.

Conclusion

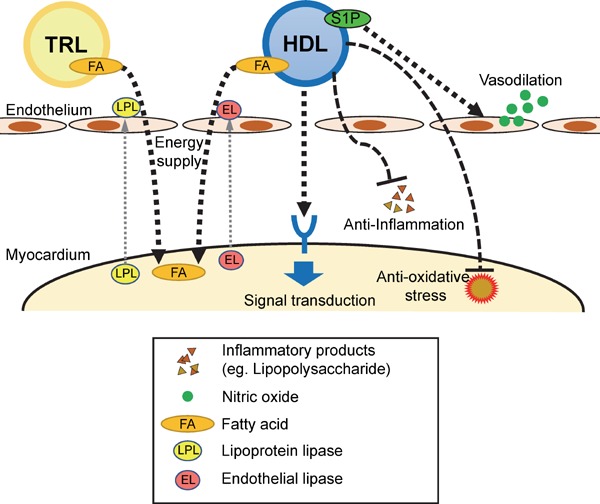

Increasing evidence in clinical and in experimental studies has underlined that HDL exerts many beneficial effects in addition to anti-atherogenic effects on the heart. Given that HF usually develops gradually on the basis of multifactorial disorders, including vascular, myocardial, and metabolic disorders, pleiotropic properties of HDL potentially help in maintaining normal cardiac function (Fig. 2). HDL may protect the myocardium by functioning as an energy fuel, NO-mediated vasodilator, and signaling molecule and by promoting anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects. Although recent clinical trials using cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors76) or niacin77) did not verify the beneficial effects of HDL-C increasing therapy, the primary outcome in these studies largely seems to depend on the onset of atherosclerotic vascular diseases. Conversely, it has been shown that pharmacological modification of HDL phospholipids can improve HDL functions78, 79). A better understanding of the direct cardioprotective effects of HDL needs to be determined in humans for seeking novel therapeutic strategies of HF.

Fig. 2.

Potential molecular mechanisms for HDL-mediated direct cardioprotective effects

HDL may protect the myocardium by fueling energy from its fatty acid (FA), stimulating nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation, activating intracellular signaling pathways, and promoting anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects. TRL, TG-rich lipoprotein.

Acknowledgments

None

Notice of Grant Support

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Conflicts of Interest

T.I. received lecture honoraria from MSD, Bayer Yakuhin, and Mochida. K.H. received research funds from MSD, Astellas, Abbott Vascular Japan, Otsuka, Mochida, Nihon Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Japan Mediphysics, Bayer Yakuhin, Fuji-Film RI, Boston Scientific, Ono Yakuhin, Sanwa Kagaku, Dainippon Sumitomo, Bristol Meyers, Kowa, Dai-ichi Sankyo, Takeda and lecture honoraria from MSD, Mochida, Kowa, Takeda, Dai-ichi Sankyo, Nihon Boehringer Ingelheim, Termo. K.H. belongs to the endowed chair by Sysmex, St. Jude Medical, and Japan Medtronic. R.T. belongs to the endowed chair by Sysmex.

References

- 1). Schocken DD, Benjamin EJ, Fonarow GC, Krumholz HM, Levy D, Mensah GA, Narula J, Shor ES, Young JB, Hong Y, American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention, American Heart Association Council on Clinical C, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular N, American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure R, Quality of C, Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working G, Functional G and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working G Prevention of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Epidemiology and Prevention, Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, and High Blood Pressure Research; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2008; 117: 2544-2565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Castelli WP, Garrison RJ, Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Kalousdian S, Kannel WB. Incidence of coronary heart disease and lipoprotein cholesterol levels. The Framingham Study. JAMA. 1986; 256: 2835-2838 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Assmann G, Schulte H, von Eckardstein A, Huang Y. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as a predictor of coronary heart disease risk. The PROCAM experience and pathophysiological implications for reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis. 1996; 124 Suppl: S11-S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Curb JD, Abbott RD, Rodriguez BL, Masaki K, Chen R, Sharp DS, Tall AR. A prospective study of HDL-C and cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene mutations and the risk of coronary heart disease in the elderly. J Lipid Res. 2004; 45: 948-953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Sharrett AR, Ballantyne CM, Coady SA, Heiss G, Sorlie PD, Catellier D, Patsch W, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study G Coronary heart disease prediction from lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, lipoprotein( a), apolipoproteins A-I and B, and HDL density subfractions: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 2001; 104: 1108-1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr., Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr., Stone NJ, National Heart L, Blood I, American College of Cardiology F and American Heart A Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel Ⅲ guidelines. Circulation. 2004; 110: 227-239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). deGoma EM, deGoma RL, Rader DJ. Beyond high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels evaluating high-density lipoprotein function as influenced by novel therapeutic approaches. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51: 2199-2211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Nofer JR, Kehrel B, Fobker M, Levkau B, Assmann G, von Eckardstein A. HDL and arteriosclerosis: beyond reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis. 2002; 161: 1-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Craig WY, Palomaki GE, Haddow JE. Cigarette smoking and serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations: an analysis of published data. BMJ. 1989; 298: 784-788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Shennan NM, Seed M, Wynn V. Variation in serum lipid and lipoprotein levels associated with changes in smoking behaviour in non-obese Caucasian males. Atherosclerosis. 1985; 58: 17-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Horio T, Miyazato J, Kamide K, Takiuchi S, Kawano Y. Influence of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol on left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic function in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003; 16: 938-944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Wang TD, Lee CM, Wu CC, Lee TM, Chen WJ, Chen MF, Liau CS, Sung FC, Lee YT. The effects of dyslipidemia on left ventricular systolic function in patients with stable angina pectoris. Atherosclerosis. 1999; 146: 117-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Kerola T, Nieminen T, Hartikainen S, Sulkava R, Vuolteenaho O, Kettunen R. High-density lipoprotein is superior to B-type natriuretic peptide as a marker of systolic dysfunction in an elderly general population. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2009; 69: 865-872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Okamura T, Hayakawa T, Kadowaki T, Kita Y, Okayama A, Ueshima H, Group NDR The inverse relationship between serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and all-cause mortality in a 9.6-year follow-up study in the Japanese general population. Atherosclerosis. 2006; 184: 143-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Vredevoe DL, Woo MA, Doering LV, Brecht ML, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC. Skin test anergy in advanced heart failure secondary to either ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1998; 82: 323-328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). van der Vusse GJ, van Bilsen M, Glatz JF. Cardiac fatty acid uptake and transport in health and disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2000; 45: 279-293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Augustus AS, Kako Y, Yagyu H, Goldberg IJ. Routes of FA delivery to cardiac muscle: modulation of lipoprotein lipolysis alters uptake of TG-derived FA. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003; 284: E331-E339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Mardy K, Belke DD, Severson DL. Chylomicron metabolism by the isolated perfused mouse heart. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001; 281: E357-E364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Bharadwaj KG, Hiyama Y, Hu Y, Huggins LA, Ramakrishnan R, Abumrad NA, Shulman GI, Blaner WS, Goldberg IJ. Chylomicron- and VLDL-derived lipids enter the heart through different pathways: in vivo evidence for receptor- and non-receptor-mediated fatty acid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285: 37976-37986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Braun JE, Severson DL. Regulation of the synthesis, processing and translocation of lipoprotein lipase. Biochem J. 1992; 287 (Pt 2): 337-347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Hauton D, Bennett MJ, Evans RD. Utilisation of triacylglycerol and non-esterified fatty acid by the working rat heart: myocardial lipid substrate preference. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001; 1533: 99-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Niu YG, Evans RD. Very-low-density lipoprotein: complex particles in cardiac energy metabolism. J Lipids. 2011; 2011: 189876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Takahashi S, Kawarabayasi Y, Nakai T, Sakai J, Yamamoto T. Rabbit very low density lipoprotein receptor: a low density lipoprotein receptor-like protein with distinct ligand specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992; 89: 9252-9256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996; 271: 518-520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Connelly MA, Klein SM, Azhar S, Abumrad NA, Williams DL. Comparison of class B scavenger receptors, CD36 and scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI), shows that both receptors mediate high density lipoprotein-cholesteryl ester selective uptake but SR-BI exhibits a unique enhancement of cholesteryl ester uptake. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274: 41-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Nakajima H, Ishida T, Satomi-Kobayashi S, Mori K, Hara T, Sasaki N, Yasuda T, Toh R, Tanaka H, Kawai H, Hirata K. Endothelial lipase modulates pressure overload-induced heart failure through alternative pathway for fatty acid uptake. Hypertension. 2013; 61: 1002-1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Jaye M, Lynch KJ, Krawiec J, Marchadier D, Maugeais C, Doan K, South V, Amin D, Perrone M, Rader DJ. A novel endothelial-derived lipase that modulates HDL metabolism. Nat Genet. 1999; 21: 424-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Hirata K, Dichek HL, Cioffi JA, Choi SY, Leeper NJ, Quintana L, Kronmal GS, Cooper AD, Quertermous T. Cloning of a unique lipase from endothelial cells extends the lipase gene family. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274: 14170-14175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Yasuda T, Ishida T, Rader DJ. Update on the role of endothelial lipase in high-density lipoprotein metabolism, reverse cholesterol transport, and atherosclerosis. Circ J. 2010; 74: 2263-2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010; 90: 207-258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Neubauer S. The failing heart--an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356: 1140-1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Sack MN, Kelly DP. The energy substrate switch during development of heart failure: gene regulatory mechanisms (Review). Int J Mol Med. 1998; 1: 17-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Yamashita H, Bharadwaj KG, Ikeda S, Park TS, Goldberg IJ. Cardiac metabolic compensation to hypertension requires lipoprotein lipase. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008; 295: E705-E713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Goodwin GW, Taylor CS, Taegtmeyer H. Regulation of energy metabolism of the heart during acute increase in heart work. J Biol Chem. 1998; 273: 29530-29539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Augustus AS, Buchanan J, Park TS, Hirata K, Noh HL, Sun J, Homma S, D'Armiento J, Abel ED, Goldberg IJ. Loss of lipoprotein lipase-derived fatty acids leads to increased cardiac glucose metabolism and heart dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281: 8716-8723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Arany Z, Novikov M, Chin S, Ma Y, Rosenzweig A, Spiegelman BM. Transverse aortic constriction leads to accelerated heart failure in mice lacking PPAR-gamma coactivator 1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103: 10086-10091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Kratky D, Zimmermann R, Wagner EM, Strauss JG, Jin W, Kostner GM, Haemmerle G, Rader DJ, Zechner R. Endothelial lipase provides an alternative pathway for FFA uptake in lipoprotein lipase-deficient mouse adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2005; 115: 161-167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Willson TM, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, Henke BR. The PPARs: from orphan receptors to drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2000; 43: 527-550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Ahmed W, Orasanu G, Nehra V, Asatryan L, Rader DJ, Ziouzenkova O, Plutzky J. High-density lipoprotein hydrolysis by endothelial lipase activates PPARalpha: a candidate mechanism for high-density lipoprotein-mediated repression of leukocyte adhesion. Circ Res. 2006; 98: 490-498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Ali Sheikh MS, Salma U, Zhang B, Chen J, Zhuang J, Ping Z. Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Value of Circulating miRNAs in Heart Failure Patients Associated with Oxidative Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016; 2016: 5893064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Ide T, Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Suematsu N, Hayashidani S, Ichikawa K, Utsumi H, Machida Y, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Direct evidence for increased hydroxyl radicals originating from superoxide in the failing myocardium. Circ Res. 2000; 86: 152-157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Hori M, Nishida K. Oxidative stress and left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2009; 81: 457-464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Tolle M, Pawlak A, Schuchardt M, Kawamura A, Tietge UJ, Lorkowski S, Keul P, Assmann G, Chun J, Levkau B, van der Giet M, Nofer JR. HDL-associated lysosphingolipids inhibit NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008; 28: 1542-1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Marchesi M, Booth EA, Rossoni G, Garcia RA, Hill KR, Sirtori CR, Bisgaier CL, Lucchesi BR. Apolipoprotein A-IMilano/POPC complex attenuates post-ischemic ventricular dysfunction in the isolated rabbit heart. Atherosclerosis. 2008; 197: 572-578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45). Nagao M, Toh R, Irino Y, Nakajima H, Oshita T, Tsuda S, Hara T, Shinohara M, Ishida T, Hirata KI. High-density lipoprotein protects cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress via the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway. FEBS Open Bio. 2017; 7: 1402-1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005; 17: 596-603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). Song X, Kusakari Y, Xiao CY, Kinsella SD, Rosenberg MA, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Hara K, Rosenzweig A, Matsui T. mTOR attenuates the inflammatory response in cardiomyocytes and prevents cardiac dysfunction in pathological hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010; 299: C1256-C1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48). Sciarretta S, Volpe M, Sadoshima J. Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in cardiac physiology and disease. Circ Res. 2014; 114: 549-564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49). Zhang D, Contu R, Latronico MV, Zhang J, Rizzi R, Catalucci D, Miyamoto S, Huang K, Ceci M, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Peterson KL, Guan KL, Brown JH, Chen J, Sonenberg N, Condorelli G. MTORC1 regulates cardiac function and myocyte survival through 4E-BP1 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010; 120: 2805-2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50). Yndestad A, Damas JK, Oie E, Ueland T, Gullestad L, Aukrust P. Role of inflammation in the progression of heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2007; 9: 236-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51). Niebauer J, Volk HD, Kemp M, Dominguez M, Schumann RR, Rauchhaus M, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ, Anker SD. Endotoxin and immune activation in chronic heart failure: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 1999; 353: 1838-1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52). Rauchhaus M, Coats AJ, Anker SD. The endotoxin-lipoprotein hypothesis. Lancet. 2000; 356: 930-933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53). Flegel WA, Baumstark MW, Weinstock C, Berg A, Northoff H. Prevention of endotoxin-induced monokine release by human low- and high-density lipoproteins and by apolipoprotein A-I. Infect Immun. 1993; 61: 5140-5146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54). Ulevitch RJ, Johnston AR, Weinstein DB. New function for high density lipoproteins. Their participation in intravascular reactions of bacterial lipopolysaccharides. J Clin Invest. 1979; 64: 1516-1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55). Levine DM, Parker TS, Donnelly TM, Walsh A, Rubin AL. In vivo protection against endotoxin by plasma high density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993; 90: 12040-12044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56). Hubsch AP, Casas AT, Doran JE. Protective effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein in rabbit gram-negative bacteremia models. J Lab Clin Med. 1995; 126: 548-558 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57). Hara T, Ishida T, Kojima Y, Tanaka H, Yasuda T, Shinohara M, Toh R, Hirata K. Targeted deletion of endothelial lipase increases HDL particles with anti-inflammatory properties both in vitro and in vivo. J Lipid Res. 2011; 52: 57-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58). Levkau B, Hermann S, Theilmeier G, van der Giet M, Chun J, Schober O, Schafers M. High-density lipoprotein stimulates myocardial perfusion in vivo. Circulation. 2004; 110: 3355-3359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59). Nofer JR, van der Giet M, Tolle M, Wolinska I, von Wnuck Lipinski K, Baba HA, Tietge UJ, Godecke A, Ishii I, Kleuser B, Schafers M, Fobker M, Zidek W, Assmann G, Chun J, Levkau B. HDL induces NO-dependent vasorelaxation via the lysophospholipid receptor S1P3. J Clin Invest. 2004; 113: 569-581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60). Yuhanna IS, Zhu Y, Cox BE, Hahner LD, Osborne-Lawrence S, Lu P, Marcel YL, Anderson RG, Mendelsohn ME, Hobbs HH, Shaul PW. High-density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor-BI activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat Med. 2001; 7: 853-857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61). Saddar S, Mineo C, Shaul PW. Signaling by the high-affinity HDL receptor scavenger receptor B type I. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010; 30: 144-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62). Sattler K, Levkau B. Sphingosine-1-phosphate as a mediator of high-density lipoprotein effects in cardiovascular protection. Cardiovasc Res. 2009; 82: 201-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63). Zhang B, Tomura H, Kuwabara A, Kimura T, Miura S, Noda K, Okajima F, Saku K. Correlation of high density lipoprotein (HDL)-associated sphingosine 1-phosphate with serum levels of HDL-cholesterol and apolipoproteins. Atherosclerosis. 2005; 178: 199-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64). Keul P, Sattler K, Levkau B. HDL and its sphingosine-1-phosphate content in cardioprotection. Heart Fail Rev. 2007; 12: 301-306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65). Blaho VA, Hla T. An update on the biology of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Lipid Res. 2014; 55: 1596-1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66). Means CK, Brown JH. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signalling in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2009; 82: 193-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67). Tao R, Hoover HE, Honbo N, Kalinowski M, Alano CC, Karliner JS, Raffai R. High-density lipoprotein determines adult mouse cardiomyocyte fate after hypoxia-reoxygenation through lipoprotein-associated sphingosine 1-phosphate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010; 298: H1022-H1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68). Frias MA, Lang U, Gerber-Wicht C, James RW. Native and reconstituted HDL protect cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2010; 85: 118-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69). Theilmeier G, Schmidt C, Herrmann J, Keul P, Schafers M, Herrgott I, Mersmann J, Larmann J, Hermann S, Stypmann J, Schober O, Hildebrand R, Schulz R, Heusch G, Haude M, von Wnuck Lipinski K, Herzog C, Schmitz M, Erbel R, Chun J, Levkau B. High-density lipoproteins and their constituent, sphingosine-1-phosphate, directly protect the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo via the S1P3 lysophospholipid receptor. Circulation. 2006; 114: 1403-1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70). Herzog C, Schmitz M, Levkau B, Herrgott I, Mersmann J, Larmann J, Johanning K, Winterhalter M, Chun J, Muller FU, Echtermeyer F, Hildebrand R, Theilmeier G. Intravenous sphingosylphosphorylcholine protects ischemic and postischemic myocardial tissue in a mouse model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2010; 2010: 425191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71). Morel S, Frias MA, Rosker C, James RW, Rohr S, Kwak BR. The natural cardioprotective particle HDL modulates connexin43 gap junction channels. Cardiovasc Res. 2012; 93: 41-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72). Frias MA, Lecour S, James RW, Pedretti S. High density lipoprotein/sphingosine-1-phosphate-induced cardioprotection: Role of STAT3 as part of the SAFE pathway. JAKSTAT. 2012; 1: 92-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73). Frias MA, Pedretti S, Hacking D, Somers S, Lacerda L, Opie LH, James RW, Lecour S. HDL protects against ischemia reperfusion injury by preserving mitochondrial integrity. Atherosclerosis. 2013; 228: 110-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74). Shende P, Plaisance I, Morandi C, Pellieux C, Berthonneche C, Zorzato F, Krishnan J, Lerch R, Hall MN, Ruegg MA, Pedrazzini T, Brink M. Cardiac raptor ablation impairs adaptive hypertrophy, alters metabolic gene expression, and causes heart failure in mice. Circulation. 2011; 123: 1073-1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75). Shende P, Xu L, Morandi C, Pentassuglia L, Heim P, Lebboukh S, Berthonneche C, Pedrazzini T, Kaufmann BA, Hall MN, Ruegg MA, Brink M. Cardiac mTOR complex 2 preserves ventricular function in pressure-overload hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2016; 109: 103-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76). Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Komajda M, Lopez-Sendon J, Mosca L, Tardif JC, Waters DD, Shear CL, Revkin JH, Buhr KA, Fisher MR, Tall AR, Brewer B, Investigators I Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357: 2109-2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77). Investigators A-H. Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365: 2255-2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78). Tanaka N, Ishida T, Nagao M, Mori T, Monguchi T, Sasaki M, Mori K, Kondo K, Nakajima H, Honjo T, Irino Y, Toh R, Shinohara M, Hirata K. Administration of high dose eicosapentaenoic acid enhances anti-inflammatory properties of high-density lipoprotein in Japanese patients with dyslipidemia. Atherosclerosis. 2014; 237: 577-583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79). Tanaka N, Irino Y, Shinohara M, Tsuda S, Mori T, Nagao M, Oshita T, Mori K, Hara T, Toh R, Ishida T, Hirata KI. Eicosapentaenoic Acid-Enriched High-Density Lipoproteins Exhibit Anti-Atherogenic Properties. Circ J. 2018; 82: 596-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]