The paucity of assays to determine physiologically relevant OP exposure presents an opportunity to explore the use of fecal bacteria as sentinels in combination with urine to assess changes in the exposed host. Recent advances in sequencing technologies and computational approaches have enabled researchers to survey large community-level changes of gut bacterial biota and metabolomic changes in various biospecimens. Here, we profiled changes in fecal bacterial biota and urine metabolome following a chemical warfare nerve agent exposure. The significance of this work is a proof of concept that the fecal bacterial biota and urine metabolites are two separate biospecimens rich in surrogate indicators suitable for monitoring OP exposure. The larger value of such an approach is that assays developed on the basis of these observations can be deployed in any setting with moderate clinical chemistry and microbiology capability. This can enable estimation of the affected radius as well as screening, triage, or ruling out of suspected cases of exposures in mass casualty scenarios, transportation accidents involving hazardous materials, refugee movements, humanitarian missions, and training settings when coupled to an established and validated decision tree with clinical features.

KEYWORDS: soman, gut microbiome, 16S rRNA gene, urine metabolome

ABSTRACT

The experimental pathophysiology of organophosphorus (OP) chemical exposure has been extensively reported. Here, we describe an altered fecal bacterial biota and urine metabolome following intoxication with soman, a lipophilic G class chemical warfare nerve agent. Nonanesthetized Sprague-Dawley male rats were subcutaneously administered soman at 0.8 (subseizurogenic) or 1.0 (seizurogenic) of the 50% lethal dose (LD50) and evaluated for signs of toxicity. Animals were stratified based on seizing activity to evaluate effects of soman exposure on fecal bacterial biota and urine metabolites. Soman exposure reshaped fecal bacterial biota by altering Facklamia, Rhizobium, Bilophila, Enterobacter, and Morganella genera of the Firmicutes and Proteobacteria phyla, some of which are known to hydrolyze OP chemicals. However, analogous changes were not observed in the bacterial biota of the ileum, which remained the same irrespective of dose or seizing status of animals after soman intoxication. However, at 75 days after soman exposure, the bacterial biota stabilized and no differences were observed between groups. Interestingly, in considering just the seizing status of animals, we found that the urine metabolomes were markedly different. Leukotriene C4, kynurenic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, norepinephrine, and aldosterone were excreted at much higher rates at 72 h in seizing animals, consistent with early multiorgan involvement during soman poisoning. These findings demonstrate the feasibility of using the dysbiosis of fecal bacterial biota in combination with urine metabolome alterations as forensic evidence for presymptomatic OP exposure temporally to enable administration of neuroprotective therapies of the future.

IMPORTANCE The paucity of assays to determine physiologically relevant OP exposure presents an opportunity to explore the use of fecal bacteria as sentinels in combination with urine to assess changes in the exposed host. Recent advances in sequencing technologies and computational approaches have enabled researchers to survey large community-level changes of gut bacterial biota and metabolomic changes in various biospecimens. Here, we profiled changes in fecal bacterial biota and urine metabolome following a chemical warfare nerve agent exposure. The significance of this work is a proof of concept that the fecal bacterial biota and urine metabolites are two separate biospecimens rich in surrogate indicators suitable for monitoring OP exposure. The larger value of such an approach is that assays developed on the basis of these observations can be deployed in any setting with moderate clinical chemistry and microbiology capability. This can enable estimation of the affected radius as well as screening, triage, or ruling out of suspected cases of exposures in mass casualty scenarios, transportation accidents involving hazardous materials, refugee movements, humanitarian missions, and training settings when coupled to an established and validated decision tree with clinical features.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the serious health threat posed to communities, organic derivatives of phosphorus (organophosphorus [OP])-containing acids have a wide range of applications in modern society (1–3). OP-containing products are in excessive use worldwide for the control of agricultural or household pests. OP-containing pesticides account for almost 38% of all pesticides used across the globe, leading to nearly 3 million poisonings, over 200,000 deaths annually, and the contamination of numerous ecosystems (4). In addition, application of OP derivatives as agents of war and terrorism in the form of nerve agents poses a significant threat to both civilians and the warfighter. Exposure to OP leads to various degrees of neurotoxicity due to cholinergic receptor hyperactivity, mediated primarily by the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) (5). The excessive accumulation of acetylcholine leads to severe physiological complications that may manifest as muscarinic symptoms (e.g., lacrimation, salivation, diarrhea, miosis, and bradycardia), nicotinic symptoms (e.g., tachycardia, hypertension, convulsions, and paralysis of skeletal and respiratory muscles), and death (1–3, 6, 7).

Soman (pinacolyl methylphosphonofluoridate or GD [German agent D]) is one of the G class nerve agents (volatile agents associated with inhalation toxicity) that inhibit AChE much more rapidly but less specifically than V class nerve agents (viscous agents associated with transdermal toxicity) (2, 6, 8). Whole-body autoradiography studies in mice revealed that intravenously administered tritiated soman ([3H]soman) spreads through the entire body in less than 5 min (9). High levels of accumulation were noted in the lungs, skin, gallbladder, intestinal lumen, and urine during the first 24 h. [3H]pinacolyl methylphosphoric acid ([3H]PMPA), a hydrolyzed acid and primary metabolite of soman, was found to be concentrated in specific organs such as lungs, heart, and kidneys within minutes of [3H]soman administration, which reflected the highly reactive (i.e., rapidly aging) nature of soman in vivo (10). Significant amounts of soman were also detected in red blood cells, a major esterase depot, compared to the plasma. In addition, those studies revealed that the common route of excretion for PMPA, a major soman metabolite, was via urine and the intestinal lumen content (9, 11). Interestingly, only trace amounts of [3H]soman, [3H]PMPA, or [3H]methylphosphonic acid (hydrolyzed PMPA) were observed in the central nervous system (CNS). Current clinical nerve agent exposure assessments are primarily based on overt physiological reactions such as convulsions, loss of consciousness, and salivation for high-dose exposures or pupil constriction and respiratory distress for low-dose exposures (12, 13). Recent studies have also demonstrated the feasibility of identifying OP hydrolysis products in hair and nail clippings to verify nerve agent exposure after 30 days (13, 14). Hence, monitoring asymptomatic exposure or verifying suspected exposure during the presymptomatic phase using minimally invasive and rapid molecular methods represents an ideal approach and capability. Thus, identification of new surrogate biomarkers of toxicity and/or exposure to soman and other OP chemicals is essential from both a clinical and a public health standpoint, especially for triaging population-level exposures.

Using an omics approach, we have assessed the potential value of correlations between changes in fecal bacterial biota or urine metabolites and OP exposure to determine if these biospecimens are suitable for diagnostic use for exposure surveillance and monitoring in a rat model of soman exposure. More importantly, we filled in a knowledge gap regarding how OP exposure directly or indirectly impacts bacterial communities of the mammalian gut and alters the global urine metabolic profile. For over 20 years, specific species of the Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria phyla have been implicated in enhanced biodegradation of OP pesticides in the bioremediation field. Therefore, exploring the role of the microbiome in a mammalian host's response to OP is the next logical step (4, 15). Furthermore, recent advances in sequencing technologies have enabled a detailed analysis of structural changes in the gut microbiome, revealing the dynamic ecosystem of the bacterial biota and its essential role in health and disease. We also identified urine as a suitable specimen type for investigation in this study because urine consists of numerous metabolites as outputs from multiple pathways and provides a snapshot of both local and systemic physiological changes (16). With these concerns in mind, we focused our efforts on exploring and describing soman-induced dysbiosis of the gut microbiota and alterations in the urine metabolome.

RESULTS

Clinical manifestation of soman insult.

To establish soman-induced toxicity with and without seizure, Sprague-Dawley rats were subcutaneously injected with saline solution or with a 0.8 median lethal dose (LD50) (subseizurogenic and unmitigated by treatment) or a 1.0 LD50 (seizurogenic and mitigated by treatment) exposure equivalent of soman. To reduce mortality, the animals given 1.0 LD50 were also administered atropine sulfate and HI-6 1 min after exposure. Rats that developed seizures at 1 LD50 were given diazepam to control seizing. Approximately 42% of the animals exposed to soman (0.8 or 1.0 LD50) experienced seizure irrespective of the dose or the medical treatment regimen administered. As expected, control rats did not experience seizure from administration of the vehicle. Seizing animals experienced notable weight loss after soman poisoning (Fig. 1A). The Racine scale score, representing a quantitative assessment of seizure-related activities such as degrees of tremors, convulsions, and seizures, was significantly higher in seizing subjects than in nonseizing subjects, as expected (Fig. 1B) (17–19). On the basis of electroencephalograph (EEG) activity, body weight, and Racine score, we broadly categorized our analysis groups into a nonseizing group (no seizure, n = 13) and a seizing group (exposure seizure or sustained seizure, n = 10). We also further subdivided cohorts based on dose because of seizure differences (Fig. 1C and D). Fecal matter, urine, and tissues were harvested from animals to examine the gut microbiota and urine metabolic changes due to the soman insult.

FIG 1.

Clinical manifestation of toxicity after soman exposure. Panel A represents trends in body weight changes based on seizing status of rats before and after soman exposure. Panel B represents Racine score differences based on seizing status of rats after soman exposure. Panels C and D represent seizure activities (latency to seizure [C] or seizure duration [D] during 72 h of monitoring) of rats exposed to 0.8 LD50 of soman without treatment (unmitigated seizure model, n = 4) or 1.0 LD50 of soman and treated with a medical countermeasure (mitigated seizure model, n = 6) a minute after exposure.

Taxonomic changes to soman exposure.

To assess the effect of soman exposure on the bacterial biota, we sequenced the V3 and V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA from the feces and ileum of all animals at 72 h. Collecting and sequencing specimens from individual animals enabled us to assess the effect of dose- or seizing-status-driven changes in individual bacterial compositions. By measuring multiple alpha diversity estimates within a dose (0.8 LD50 or 1.0 LD50) or seizing status (nonseizing or seizing) for specimens, we found statistically significantly (P < 0.05) altered diversity in the fecal bacterial biota of seizing animals at both the subseizurogenic 0.8 LD50 and seizurogenic 1.0 LD50 levels (with a pronounced effect in seizing animals with the 0.8 LD50 exposure) that was markedly different from that seen with the control or nonseizing groups (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Measuring levels of alpha diversity between the ileum specimens of control and soman-exposed animals, however, a higher degree of taxon similarity was observed irrespective of dose or seizing status (Fig. S1B) of specimens. The bacterial biota of the ileum was not altered by exposure to soman, while the fecal bacterial biota was substantially altered.

In order to investigate if organism abundance accounted for the alpha diversity differences observed between the fecal and ileum bacterial biota in response to soman insult, we rank ordered all phyla identified in the study based on relative abundances (data not shown). To our surprise, no differences between the fecal and ileum bacterial phylum abundance distributions were observed. In both fecal and ileum specimens, as expected, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes accounted for the most abundant phyla followed by Verrucomicrobia, Tenericutes, and Actinobacteria. However, the relative abundances of all the phyla within the ileum were evenly distributed around the 10% level whereas the phyla within the fecal specimens displayed a wide range of distribution (from 6% to 18%) (data not shown). To further understand if soman exposure-driven bacterial biota differences were attributable to dose or seizure individually, we measured beta diversity levels using weighted UniFrac distances between specimens (fecal or ileum) and visualized the output using principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) (Fig. S2). However, due to overlapping clusters, the PCoA was unable to classify any of the groups into significant clusters based on dose or seizing status in either the ileum or fecal specimens.

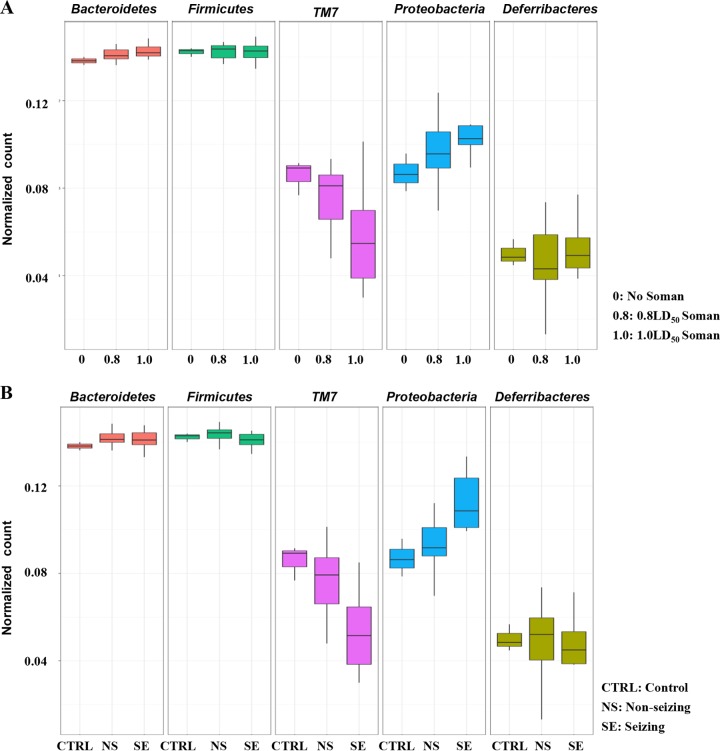

Effect of soman exposure on fecal bacterial biota composition.

Next, we examined the microbial communities of the feces and ileum of each subject and quantified each phylum to decipher where microbially diverse populations were substantially altered by exposure to soman, based on dose or seizure status. Several structural changes were observed in the fecal microbiota compositions correlating with the dose or seizure status of animals (Fig. 2). We found that the relative abundance of fecal TM7 phylum was reduced in response to increasing doses of soman and the seizure status of animals concurrently. In contrast, increasing relative abundances of fecal Proteobacteria and Cyanobacteria trended with increases in soman dose insult and seizing status of animals (Fig. S3). However, the relative abundances of Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Tenericutes, and Verrucomicrobia phyla were unchanged in response to the soman dose or seizing status of animals. The Bacteroidetes phylum showed a positive trend of a relative abundance increase, although the data were not statistically significant. Similar microbial community composition analyses were also completed for ileum specimens collected from each individual subject to identify if any changes were masked during the initial analyses (Fig. S4). Consistent with previous findings in the ileum, no significant structural bacterial biota changes were observed in any subjects in response to an increase in dose or seizing status.

FIG 2.

Trends in relative abundances of fecal bacterial biota (phylum level) based on dose (panel A) or seizing status (panel B) of rats 72 h after soman exposure. TM7 phylum bacteria exhibited decreased normalized counts with increasing dose or seizing status, whereas the inverse was observed for the Proteobacteria phylum bacteria. CTRL, control; NS, nonseizing after exposure; SE, seizing after exposure.

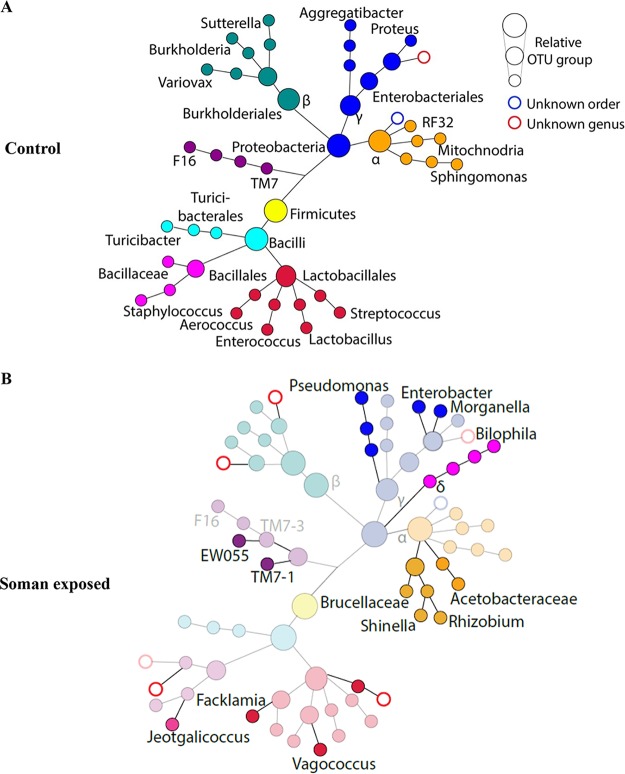

Furthermore, to measure the bacterial biota diversity and relative abundance (with respect to quantitative and qualitative analysis), we looked into higher phylogenetic resolutions and taxonomic breakdowns. Distinct bacterial populations were observed at the genus level of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria in the fecal specimens of soman-exposed animals (Fig. 3). The Facklamia genus of the Aerococcaceae family was detected only in the fecal specimens of soman-exposed rats and not in the ileum tissue content. The Rhizobium, Bilophila, Enterobacter, and Morganella genera of the Proteobacteria phylum exhibited expansion in the soman-exposed rats similar to that observed for the Facklamia genus. Interestingly, the Rhizobium genus, formerly known as Agrobacterium, was primarily identified in the lower-dose (0.8 LD50) soman exposure group whereas the Bilophila, Blautia, Enterobacter, and Morganella genera were detected in all soman doses irrespective of the seizing status of animals (Fig. S5). Furthermore, several unclassified operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were observed for Alcaligenaceae and Comamonadaceae of the Burkholderiales order and some Enterobacteriaceae families, primarily in the seizing animals with high soman dose exposure, and these genus clusters were not observed in the control group or the group with low soman dose exposure. All differences in bacterial biota composition described here were observed only at the 72-h time point and were negligible at 75 days postexposure (data not shown).

FIG 3.

SPADE-like analysis data showing taxonomic changes in bacteria of the Proteobacteria and Firmicutes (Bacilli only) phyla. Circle size is assigned by automatically binning normalized OTU counts into any of the three sizes. Distances between circles were assigned arbitrarily. Colors are added as a visual aid for following branches and do not have any connotation. Panel A data represent average OTU counts of fecal bacterial biota for the two phyla detected in soman-unexposed control animals. Panel B data show representative averages of OTU counts of bacterial biota detected after exposure (solid circles) compared to bacterial biota of unexposed control mice (faded circles). Unassigned OTU clusters at the order or genus level are represented by blue or red circles.

Soman exposure alters the urine metabolome.

The untargeted metabolomic profiling of biological substrates within a biospecimen provides direct and simultaneous measurements of the catabolic biochemical outputs that make up a given phenotype (20). Comparative metabolomics profiling of urine specimens was performed to assess soman exposure-associated metabolic alterations at 72 h postexposure, for seizing and nonseizing animals. XCMS software was used to preprocess metabolomics data to generate an analysis matrix of mass over charge, retention time, fold change, and P value data for over 500 unique metabolite peaks identified from both positive- and negative-mode analyses. Volcano plots constructed with MetaboAnalyst v3.0 were used to visualize and enrich for metabolites with ≥2-fold change at a P value of <0.05 (Fig. S6). Furthermore, PCA was used to visualize whether the seizing and nonseizing groups clustered separately (Fig. S7). At the 72-h time point, we found >200 metabolite peaks with >2.0-fold change, among which 9 analytes had >20-fold change in seizing rats rather than nonseizing rats. Many of these metabolites with >20-fold change appear to be either food-derived metabolites such as methylmaysin and acetylpicropolin or cresol derivatives. We also found a large fraction of modified amino acids (such as acetylated, methylated, or formylated) common urine solutes along with many phenyl and indole compounds. We used an in-house algorithm to identify bacterial metabolites that are known to be detected in urine. Hence, we identified routine urine metabolites associated with microbial origin such as p-cresol, d-alanine, and phenylacetic acid. Interestingly, these metabolites were detected at a significantly higher rate (>5-fold change) in the urine of seizing rats than in that of nonseizing rats. The tryptophan catabolism by-product kynurenic acid, the inflammatory lipid leukotriene C4 (LTC4), and the neurotransmitter norepinephrine were also secreted in the urine at a significantly higher rate in seizing animals (Table 1) (21). However, urinary citric acid levels remained unaltered between seizing and nonseizing animals, suggesting that the presence of physiological indicators of physiological dysregulation (acidemia and inflammation) in the urine of soman-exposed animals was not primarily the result of kidney injury.

TABLE 1.

Summary of soman exposure-altered urine solutea

| ESI mode | Fold change in metabolite peak | P value | Solute name | Solute formula | RT (min) | m/z | dppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEG | 0.45193 | 0.00160 | Guanosine-3′,5′-diphosphate | C10H15N5O11P2 | 4.58 | 442.0211 | 9.092775 |

| NEG | 0.4864 | 0.00773 | Citric acid | C6H8O7 | 0.42 | 191.0192 | 2.781159 |

| NEG | 2.3912 | 0.04993 | Uric acid | C5H4N4O3 | 0.34 | 167.0199 | 6.901621 |

| POS | 2.2575 | 0.00119 | Kynurenic acid | C10H7NO3 | 1.57 | 190.0503 | 2.260052 |

| POS | 2.7 | 0.00409 | Quinoline | C9H7N | 3.13 | 130.0645 | 4.847519 |

| POS | 3.4701 | 0.00000 | Leukotriene C4 | C30H47N3O9S | 2.08 | 626.3129 | 3.806747 |

| POS | 11.883 | 0.00033 | Norepinephrine sulfate | C8H11NO6S | 3.17 | 250.0398 | 7.291454 |

| POS | 3.0192 | 0.00018 | 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid | C10H9NO3 | 1.62 | 192.0666 | 5.670386 |

| NEG | 27.481 | 0.0018 | p-Cresol | C7H8O | 3.11 | 107.0501 | 1.270889 |

| POS | 6.8123 | 0.0301 | Phenylacetic acid | C8H8O2 | 2.96 | 137.060 | 4.37399 |

| POS | 6.572 | 0.00467 | N-Butyryl-l-homoserine lactone | C8H13NO3 | 2.39 | 172.0968 | 0.089186 |

| POS | 3.0117 | 0.00435 | l-Carnitine | C7H15NO3 | 0.39 | 162.1123 | 1.041845 |

| POS | 4.0547 | 0.00140 | Glycine | C2H5NO2 | 2.45 | 76.0397 | 5.287456 |

| POS | 4.2532 | 0.00000 | Neuraminic acid | C9H17NO8 | 0.39 | 268.1006 | 7.883747 |

| POS | 6.8278 | 0.00337 | Retinoyl glucuronide | C26H36O8 | 5.48 | 477.2527 | 9.227536 |

| POS | 7.083 | 0.00276 | Glutathione | C10H17N3O6S | 3.16 | 308.091 | 0.198757 |

| POS | 7.6032 | 0.00970 | d-Alanine/l-alanine | C3H7NO2 | 0.69 | 90.0557 | 8.396408 |

| POS | 5.78 | 0.00861 | Aldosterone | C21H28O5 | 5.72 | 361.2036 | 7.455842 |

Data represent results of analysis of urine metabolites whose excretion significantly differed (P < 0.05) in seizing animals compared to nonseizing animals. These metabolites were validated by an additional independent experiment. NEG, negative; POS, positive; RT, retention time.

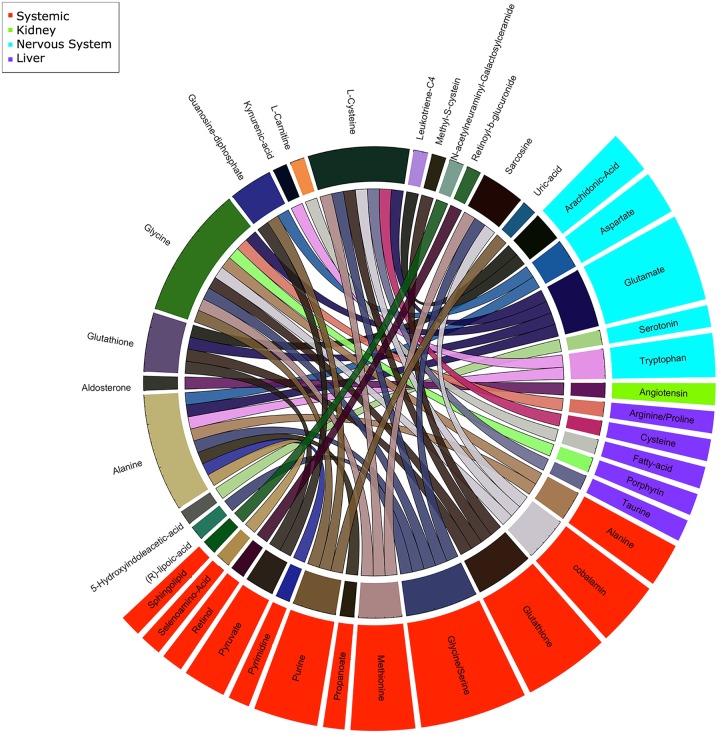

To gain insights into biological networks perturbed by soman in seizing rats, we annotated all molecular networks associated with candidate metabolites identified at the 72-h time point in an unbiased manner using publicly available databases. Consistent with the neurotoxicity pathology of soman assault, large proportions of the metabolites in the urine of seizing animals were primarily related to nervous system signaling activity representing norepinephrine and serotonergic pathway products (data not shown). Next, we narrowed our pathway annotation to consider only the metabolites with the best peak matches (such as highest mass accuracy [lowest difference between the query mass and the metabolite mass in parts per million {dppm}] and frequent database hits) and to manually remove unlikely identifications, such as drug action pathways, to restrict off-target hits in our annotation algorithm. This careful focus of the data input revealed key molecular networks (catabolic processes) reflective of products associated with kidney function, canonical central nervous system (CNS) inflammation, amino acid and lipid metabolism, and vitamin absorption (Fig. 4). To increase the confidence in this analysis, we have focused our study on only a select set of metabolites that were validated.

FIG 4.

Snapshot of validated altered urine metabolites, affected candidate site, and parent pathways. The Circos image represents urine metabolites significantly (P < 0.05) altered in seizing animals (outer-ring labels on white background) and associated catabolic pathways (outer-ring ribbons) and sites (ribbon colors).

DISCUSSION

Here, we employed a high-throughput systems approach to survey changes in the gut bacterial biota and urine metabolites and to explore new targets with potential diagnostic value for OP exposure and toxicity in noninvasively collected specimens. We initially noted that seizing subjects were significantly different from controls and nonseizing subjects on the basis of multiple parameters, including alpha diversity measures. However, composition analysis indicated that the TM7 and Cyanobacteria phyla were probably the main drivers of the large observed alpha diversity differences whereas the Proteobacteria phylum was a modest contributor to those observed differences. Unfortunately, Cyanobacteria species represent organisms such as chloroplasts, and the TM7 phylum is not well understood. Due to limited knowledge, we concluded that data from these two phyla are insufficient for drawing meaningful conclusions with respect to the observed biological differences at this time. Thus, we focused our efforts on close examination of the genus compositions of the various phyla identified in our study, especially Proteobacteria. To this end, we noted the presence of Facklamia genus, a member of the Firmicutes, only in the feces and not in the ileum digesta of rats exposed to soman. This genus is associated only minimally with invasive disease, but it is known to be occasionally isolated from specimens of urinary tract infections and chorioamnionitis infections (22). We also observed Blautia, another Firmicutes family member, which was highly enriched only in the feces of soman-exposed animals. Unfortunately, limited data are available regarding the metabolic functions, specifically, hydrolysis, reduction, or esterification of xenobiotics, for these organisms within the gut and additional investigations are needed in this area.

Many of the organophosphate-degrading (opd) genes implicated in the enhanced degradation of OP chemicals are located on mobile elements known to be transferred between organisms (23). In addition, a majority of these genes exhibit broad specificity and activity against OP chemicals either by directly hydrolyzing the phosphoester bonds in organophosphorus compounds or by further degradation of methylphosphonate esters to reduce the toxicity or reactivation of OP (4, 23). Such genes have been isolated from select species of the Flavobacterium, Pseudomonas, Alteromonas, Burkholderia, Bacillus, Alcaligenes, Enterobacter, and Rhizobium genera, to name a few. Since we had identified multiple genera such as Enterobacter and Rhizobium that are known to be carriers of opd genes and involved in enhanced biodegradation of OP chemicals, we investigated opd genes from pooled fecal specimens and detected several targets that indicated that the expected gene templates were present in the bacterial biota (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). However, we do not have evidence for a specific species that is carrying the opd gene templates or transcript data supporting the idea of active expression of the genes (no RNA or protein). Rhizobium, an Alphaproteobacteria, is an aerobic, oxidase-positive, Gram-negative bacillus isolated from the soil environment and is known to cause plant tumors (24, 25). Currently, there is limited information about which species of Rhizobium reside in the gut of mammals as routine commensals (which would be identifiable with a whole-genome sequencing approach) and whether these have a functional role(s) (15, 24). The Bilophila genus is a Deltaproteobacteria, where B. wadsworthia is the only known species in this genus. B. wadsworthia is known to thrive on taurine and H2 production, especially around highly fermentative sites (26). We found that B. wadsworthia was highly enriched and detectable in all soman-exposed cohorts irrespective of dose or seizing status but not in control animals, suggesting that an unusually highly anaerobic environment could have promoted this organism's detection. Hence, we decided to validate B. wadsworthia using a PCR assay targeting 16S rRNA in fecal DNA extracts, pooled due to the limited amounts of the original specimens (Fig. S8). We observed that B. wadsworthia levels were altered across pooled groups, especially in seizing animals with high dose exposure, and that its 16S rRNA was only minimally expressed in controls.

Seizures that accompany soman intoxication lead to profound brain damage through excitotoxic cell death of neurons, accompanied by neuroinflammation (27). Along this line, we detected elevated levels of tryptophan catabolism (>2-fold change), revealed by the detection of kynurenic acid and quinoline, in the urine of seizing animals. Kynurenic acid is a putative neuroprotective metabolite and an antagonist of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (21, 28, 29). Elevated levels of quinolone indicate overall increased systemic tryptophan catabolism during soman intoxication in seizing animals, presumably driven by inflammation in the brain, known to induce expression of tryptophan-degrading indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (28, 29). This notion of the inflammatory neuropathology of soman exposure was further supported by the detection of increased systemic levels of the eicosanoid inflammatory mediator leukotriene C4 (LTC4) in the urine of seizing animals. LTC4 is one of the cysteinyl leukotrienes (cys-LTs) generated by the enzymatic oxidation of arachidonic acid, a fatty acid released from neuronal membrane glycerophospholipids during a secondary phase of brain injury (via a cascade of physiological reactions to primary injury) (30, 31). Furthermore, after acute soman intoxication and seizure onset, high levels of acetylcholine accumulate in the CNS. This is followed by decreased levels of norepinephrine, aspartate, and glutamate (GLU) (i.e., excitatory amino acid [EAA] neurotransmitters) in the brain (5, 32). After neuronal damage, the sustainment of seizures involves increases in concentration of EAAs such as GLU along with norepinephrine, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]), and its metabolite 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA) (27). In our experimental system, the primary stimulant soman is known to cause severe neuropathology, specifically, inflammation of the CNS. Consistent with this notion, we observed and validated increased levels of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine (>11-fold change) and the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA and increased levels of the cys-LT LTC4 in the urine metabolite profile of seizing animals, clearly indicating increased inflammation associated with CNS neuropathology. Aldosterone is an essential mineralocorticoid hormone directly involved in the regulation of sodium absorption and potassium excretion in the kidney, salivary glands, sweat glands, and colon (33). Elevated levels of aldosterone are known to alter glomerular structure and function via pro-oxidative and profibrotic changes (34). Hence, aldosterone increases glomerular permeability to albumin, leading to increased protein urinary excretion. We found that urinary excretion of aldosterone is more than 5 times higher in seizing rats than in nonseizing rats, suggesting that symptomatic soman exposure may cause proteinuria and increased electrolyte excretion. Furthermore, in this context, aldosterone-driven nephropathy and renal damage of modest effect are possible secondary features of soman insult that can be easily exploited for presymptomatic monitoring of exposure. However, our experimental design did not include proper specimen preservation or analysis of renal function, specifically, of levels of protein in urine, for use in readily available gold standard clinical pathology assays.

Xenobiotic metabolites of microbial origin have been previously detected in urine (35, 36). In our study, we identified a few of the most common microbial urinary metabolites, including p-cresol and phenylacetic acid (37). Both of these metabolites result from tyrosine catabolism by colon microbes and are then sulfated by the colonic epithelium, resulting in reabsorption back into the host. High levels of p-cresol sulfate are correlated with cardiovascular diseases as well as mortality of chronic kidney disease patients (35). Furthermore, the phenolic features of such compounds are speculated to mimic neurotransmitters and interfere with the blood-brain barrier (35). Consistent with our finding of dysbiosis of the gut bacterial biota, the soman-exposed animals in our study had significant increases in the levels of p-cresol (27×) and phenylacetic acid (7×) in their urine compared to nonseizing animals. However, we did not obtain enough 16S sequencing resolution for species-level information in our efforts to identify organisms, especially those associated with tyrosine catabolism such as Clostridium difficile (35).

Although this was a proof-of-concept study (i.e., a feasibility study) that applied untargeted technologies, we were able to enrich for candidate diagnostic markers both from the bacterial biota and from urine solutes and to also identify organisms with a potential role as forensic signatures of exposure. With additional resources and better-targeted technology, we plan to pursue a more detailed analysis of a large cohort of animals, specifically, to temporally populate quantitative ratios of specific bacteria and urine metabolites in male and female rats. Furthermore, we plan to profile multiple chemical nerve agents and pesticides. On the basis of these findings, one can envision moderately complex assays with a correlation matrix and a decision algorithm to enhance current clinical microbiology and urine chemistry workflows for diagnostic purposes. This would be valuable for presymptomatic-phase screening to enable disease modifying therapies, determining the radius of impact during mass exposure, and casual/passive screening of training sites and camps, as well as monitoring of refugees from noninvasive samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Kingston, NY) (250 to 300 g) were individually housed on a 12:12-h light cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Rats were weighed daily. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (IACUC U-908), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Welfare Act of 1966 (P.L. 89–544), as amended.

Surgery and EEG recording.

Rats were surgically implanted with a subcutaneous transmitter (F-40EET; Data Sciences International, Inc. [DSI], St. Paul, MN) as described by Schultz et al. (38) to record bihemispheric cortical EEG waveform activity as well as body temperature and activity throughout the duration of the experiment. Surgery was conducted under conditions of isoflurane administration (3% to 4% induction; 1.5% to 3% maintenance), and rats received buprenorphine (Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Richmond, VA) (0.03 mg/kg of body weight, subcutaneously [s.c.]) immediately after full recovery from anesthesia. Rats were allowed to recover from surgery for 7 to 14 days prior to soman exposure. RPC-1 PhysioTel receivers (DSI) were placed under the rats' home cages for EEG acquisition (24 h/day) with baseline recordings made at least 24 h prior to exposure. Data were digitized at 250 Hz and recorded using Dataquest ART 4.1 (Acquisition software; DSI).

Soman exposures.

Rats were exposed to soman at 0.8 or 1.0 LD50 (0.5 ml/kg, using 157.4 and 196.8 μg/ml, respectively) or saline solution (control) and evaluated for seizure activity. The soman LD50 for rats is 98.4 μg/ml (38). Soman was obtained from the Edgewood Chemical Biological Center (Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD). To promote survival, rats that received 1.0 LD50 of mg/kg soman were treated with medical countermeasures (MCM; an admix of 2 mg/kg atropine sulfate [ATS; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO, USA] and 93.6 mg/kg HI-6 [Starkes Associates, Buffalo, NY, USA] [0.5 ml/kg, intramuscularly {i.m.}]) at 1 min after exposure and rats that developed seizures were treated with 10 mg/kg diazepam (DZP; Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) (2 ml/kg, s.c.) at 30 min after seizure onset (with average seizure onset of 8 min).

Behavioral seizure.

Behavioral seizures were scored using a modified Racine scale (17–19) consisting of the following stages: stage 1, mastication, tongue fasciculation, oral tonus; stage 2, head tremors, head bobs; stage 3, limb clonus or tonus, body tremor; stage 4, rearing with forelimb clonus; stage 5, rearing and falling with generalized convulsions. For analysis, rats received a score corresponding to the maximum stage reached per time interval. Observations were made continuously for up to 5 h after exposure to soman.

EEG analysis.

Full-power spectral analysis of EEG, identification of epileptiform activity, and other EEG anomalies were analyzed according to methods described previously (39). EEG-recorded seizures were confirmed through visual screening and characterized by sustained frequencies and the value corresponding to the most prominent frequencies in hertz (e.g., the highest power level calculated by the MatLab program, expressed in microvolts squared per hertz). Some soman-exposed rats developed seizure activity (SE), with the seizure onset at ∼8 min for those exposed to 1.0 LD50, while others did not develop seizures.

Sample collection.

All surfaces and tools, including a guillotine, collection foils, sample tubes, saline solution bottle, and syringes, were sprayed with RNase Away. Animals were administered Fatal-Plus (sodium pentobarbital), and, once fully anesthetized, the rats were euthanized using a guillotine. Urine was collected directly from the bladder using a syringe with a 21-gauge needle, saved in RNase-free microcentrifuge tubes, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The ileum was removed and flash frozen. Digesta was flushed out by rinsing with sterile saline solution during sample processing. Organs were collected in foils and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Fresh fecal pellets were collected during rat handling and stored at −80°C for processing.

DNA extraction.

Samples were kept cold at all times before the extraction. The Ileum tissues were weighed and homogenized in 50 mM Tris-HCl (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) with 2 nM EDTA solution (Lonza) using a BeadBeater (Bio Spec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK, USA), the DNA extraction was carried out using a Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen Inc., Germantown, MD, USA), and RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) in conjunction with a Qiagen miRNeasy minikit (Qiagen). The fecal samples were weighed, RNA was extracted using a MoBio PowerSoil total RNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA), and DNA was extracted using a MoBio PowerSoil DNA elution accessory kit. The extracted DNA was used for PCR and sequencing.

Library preparation and sequencing.

We used primers that were previously designed to amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene (40). A limited-cycle PCR generated a single amplicon of ∼460 bp, and this was followed by addition of Illumina sequencing adapters and dual-index barcodes. Using paired 300-bp reads and MiSeq v3 reagents, the ends of each read were overlapped to generate high-quality, full-length reads of the V3 and V4 regions in a single run.

Data analysis.

Sequence read quality assessment, filtering, barcode trimming, and chimera detection were performed on demultiplexed sequences using the USEARCH method in the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) package (v.1.9.1) (41). OTUs were defined by clustering with 97% sequence similarity cutoffs (at 3% divergence). The representative sequence for an OTU was chosen as the most abundant sequence showing up in that OTU by collapsing identical sequences and choosing the one that was read with the most abundant sequences. Representative sequences were then aligned against the Greengenes database core set (v.gg_13_8) using the PyNAST alignment method (http://greengenes.secondgenome.com/). The minimum sequence length of 150 nucleotides (nt) and the minimum match value of 75% were used for the alignment (42, 43). The RDP Classifier program (v.2.2) was used to assign the taxonomy to the representative set of sequences using a prebuilt database of assigned sequences of a reference set (44). Alpha diversity analysis was performed using the PhyloSeq R package (www.bioconductor.org), and the Chao1 metric (to estimate the species richness), the observed-species metric (representing the count of unique OTUs found in the sample), and the phylogenetic distance (PD_whole_tree) were calculated (45). Similarly, beta diversity data were calculated using QIIME and visualized using principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) to visualize distances between samples on an x-y-z plot. The ranked-abundance profile was created using the BiodiversityR R Bioconductor package (2.7-2) to highlight the most abundant phylum in all samples. To determine the differentially abundant taxonomic groups over different groups in the soman-exposed animals versus non-soman-exposed animals at different doses and in the seizing group versus the non-seizing group, linear models were fitted using moderated standard errors and the empirical Bayes model following the trimmed mean of M-values normalization method (TMM) for normalization of OTU counts. The normalized abundance profile was created across different doses (0.8 and 1.0 LD50) of soman exposure compared with control samples; similarly, samples from seizing versus nonseizing rats were compared to non-soman-exposed control samples.

To predict the metabolites contributed per microbial composition, we used PICRUSt (v.1.0.0), an open source tool that uses precomputed gene content inference for 16S rRNA. PICRUSt uses the OTU abundance count generated using “closed-reference” OTU picking against the Greengenes database for normalization of OTU tables. Each OTU value was first divided by known as well as predicted 16S copy number abundance values (46). Final metagenome functional predictions were performed by multiplying normalized OTU abundance values by values corresponding to each predicted functional profile. Statistical hypothesis testing analysis of metagenomics profiles was performed using R to compare KEGG Orthologs (v.80.0) data between pre- and post-soman-exposed samples, and principal-coordinate analysis was also performed. The predicted metagenome functional counts were normalized using the TMM normalization method to fit linear models using the contrast function to compute fold changes by moderating the standard errors using an empirical Bayes model. Log odds and moderated t statistics corresponding to differential predicted significant metabolite data derived from KEGG Orthologs using comparisons between pre- and post-soman-exposed samples at different doses and the seizing group versus the nonseizing group were computed with a P value cutoff of ≤0.05. Significant metabolites were further annotated using an in-house metabolite annotation function with other databases such as HMDB (v.2.5), KEGG (compounds, pathways, orthologs, and reactions) (v.80.0), SMPDB (v.2.0), and FOODB (v.1.0).

Metabolomic profiling and data analysis.

Urine samples were processed using the method of Tyburski et al. (47). Briefly, the samples were thawed on ice and subjected to vortex mixing. For metabolite extraction, 20 μl of urine was mixed with 80 μl of 50% acetonitrile (in water) containing internal standards (10 μl of debrisoquine [1 mg/ml] and 50 μl of 4-nitrobenzoic acid [1 mg/ml]). The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and used for ultraperformance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-quadrupole-time of flight-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS) analysis (Xevo G2; Waters Corporation, USA). Each sample (5 μl) was injected onto a reverse-phase 50-by-2.1-mm BEH 1.7-μm-pore-size C18 column using an Acquity UPLC system (Waters Corporation, USA). The gradient mobile phase was comprised of water containing 0.1% formic acid solution (buffer A) and acetonitrile containing a 0.1% formic acid solution (buffer B). Each sample was resolved for 10 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. This approach has been extensively used for metabolomic profiling of biofluids, UPLC gradient conditions, and mass spectrometry parameters and was described in detail previously (48–50). The UPLC gradient consisted of 100% buffer A for 0.5 min, a ramp curve of 6% to 60% buffer B from 0.5 min to 4.5 min, a ramp curve of 6% to 100% buffer B from 4.5 to 8.0 min, a hold at 100% buffer B until 9.0 min, and then a ramp curve of 6% to 100% buffer A from 9.0 min to 9.2 min, followed by a hold at 100% buffer A until 10 min. The column eluent was introduced directly into the mass spectrometer by electrospray. Mass spectrometry was performed on a quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometer operating in either negative or positive electrospray ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 3.2 kV and a sampling cone voltage of 35 V. The desolvation gas flow rate was 800 liters/h, and the temperature was set to 350°C. The cone gas flow rate was 50 liters/h, and the source temperature was 150°C. The data were acquired in V mode with a scan time of 0.3 s and an interscan delay of 0.08 s. Accurate mass was maintained by infusing sulfadimethoxine (311.0814 m/z) into 50% aqueous acetonitrile (250 pg/μl) at a rate of 30 μl/min via the lockspray interface every 10 s. Data were acquired in centroid mode using a m/z mass range of 50 to 850 for TOF-MS scanning, in duplicate (technical replicates), for each sample in positive- and negative-ionization modes and checked for chromatographic reproducibility. For all profiling experiments, the sample queue was staggered by interspersing samples of the two groups to eliminate bias. Pooled sample injections performed throughout the run (one pool was created by mixing 2-μl aliquots from all 110 samples) were used as quality controls (QCs) to assess the inconsistencies that are particularly evident in large batch acquisitions in terms of retention time drifts and variations in ion intensity over time. QCs were projected in the orthogonal partial least-squares–discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) model along with the study samples to ensure that the technical performance did not impact the biological information (51). The raw data were preprocessed using XCMS software (52) for peak detection and alignment. The resultant three-dimensional data matrix consisting of mass/charge ratios with retention times and feature intensities was subjected to multivariate data analysis using MetaboAnalyst v 3.0. Quantitative descriptors of model quality for the OPLS-DA models included R2 (explained variation of the binary outcome [treatment versus control]) and Q2 (cross-validation-based predicted variation of the binary outcome). We used score plots to visualize the discriminating properties of the OPLS-DA models. The features selected via OPLS-DA were used for accurate mass-based database searches; subsequently, the identity of a subset of metabolites was confirmed using tandem mass spectrometry.

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This research complied with the Animal Welfare Act and implemented Animal Welfare regulations and the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and adhered to the principles noted in The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council [NRC], 2011). Consent for publication was not needed (human subjects did not participate in this study).

Accession number(s).

Sequences can be accessed from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at study accession no. SRP116704 (BioProject no. PRJNA401162).

Data availability.

Data generated and analyzed during this study are included in the published article and the supplemental material files, with the exception of raw urine mass spectrometry and 75-day microbiome assay data, which are available from M. Jett upon request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kirandeep Gill (Georgetown University) for technical assistance with metabolomics data as well as Matthew Rice and Julia Scheerer for editorial input.

The views, opinions, and findings contained in this report are ours and should not be construed as official Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government positions, policies, or decisions unless so designated by other official documentation. Citations of commercial organizations or trade names in this report do not constitute an official Department of the Army endorsement or approval of the products or services of these organizations. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) was not involved in the study design or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or the decision to write the manuscript and submit it for publication.

We declare no competing interests.

Support was provided by interagency agreements between BARDA, the Geneva Foundation (ARO agreement no. W911NF-13-1-0376), and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (USAMRICD) as well as a memorandum of agreement between USAMRICD and the U.S. Army Center of Environmental Health (USACEHR). The Metabolomics Shared Resource in Georgetown University (Washington, DC, USA) is partially supported by NIH/NCI/CCSG grant P30-CA051008.

D.G. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. A.G. coordinated microbiome and metabolomics analyses and obtained the samples, A.H. processed microbiome specimens and completed validation, R.K. analyzed the data, and A.K.C. completed metabolomics analysis. F.R. analyzed the EEG data, and C.R.S. conducted animal experiments. L.A.L., M.J., and R.H. conceived and designed the study and edited the manuscript. All of us read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00978-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdollahi M, Karami-Mohajeri S. 2012. A comprehensive review on experimental and clinical findings in intermediate syndrome caused by organophosphate poisoning. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 258:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marrs TC. 1993. Organophosphate poisoning. Pharmacol Ther 58:51–66. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90066-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acon-Chen C, Koenig JA, Smith GR, Truitt AR, Thomas TP, Shih TM. 2016. Evaluation of acetylcholine, seizure activity and neuropathology following high-dose nerve agent exposure and delayed neuroprotective treatment drugs in freely moving rats. Toxicol Mech Methods 26:378–388. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2016.1197992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh BK, Walker A. 2006. Microbial degradation of organophosphorus compounds. FEMS Microbiol Rev 30:428–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih T-M, McDonough JH Jr. 1997. Neurochemical mechanisms in soman-induced seizures. J Appl Toxicol 17:255–264. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misik J. 2015. Acute toxicity of some nerve agents and pesticides in rats. Drug Chem Toxicol 38:32–36. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2014.900070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassa J, Korabecny J, Sepsova V, Tumova M. 2014. The evaluation of prophylactic efficacy of newly developed reversible inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase in soman-poisoned mice - a comparison with commonly used pyidostigmine. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 115:571–576. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villa AF, Houze P, Monier C, Risede P, Sarhan H, Borron SW, Megarbane B, Garnier R, Baud FJ. 2007. Toxic doses of paraoxon alter the respiratory pattern without causing respiratory failure in rats. Toxicology 232:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadar T, Raveh L, Cohen G, Oz N, Baranes I, Balan A, Ashani Y, Shapira S. 1985. Distribution of H-3 soman in mice. Arch Toxicol 58:45–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00292616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds ML, Little PJ, Thomas BF, Bagley RB, Martin BR. 1985. Relationship between the biodisposition of [3H]soman and its pharmacological effects in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 80:409–420. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(85)90385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih ML, Mcmonagle JD, Dolzine TW, Gresham VC. 1994. Metabolite pharmacokinetics of soman, sarin and GF in rats and biological monitoring of exposure to toxic organophosphorus agents. J Appl Toxicol 14:195–199. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550140309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown MA, Brix KA. 1998. Review of health consequences from high-, intermediate- and low-level exposure to organophosphorus nerve agents. J Appl Toxicol 18:393–408. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appel AS, McDonough JH, McMonagle JD, Logue BA. 2016. Analysis of nerve agent metabolites from hair for long-term verification of nerve agent exposure. Anal Chem 88:6523–6530. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appel AS, Logue BA. 2016. Analysis of nerve agent metabolites from nail clippings by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1031:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2016.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horne I, Sutherland TD, Harcourt RL, Russell RJ, Oakeshott JG. 2002. Identification of an opd (organophosphate degradation) gene in an Agrobacterium isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:3371–3376. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3371-3376.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Contrepois K, Jiang L, Snyder M. 2015. Optimized analytical procedures for the untargeted metabolomic profiling of human urine and plasma by combining hydrophilic interaction (HILIC) and reverse-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC)-mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 14:1684–1695. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.046508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Racine R, Chipashvili S, Okujava V. 1972. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation: III. Mechanisms. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:295–299. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Racine RJ. 1972. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. I. After-discharge threshold. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:269–279. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Racine RJ. 1972. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. 2012. Innovation: metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol 13:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Lawson MA, Kelley KW. 2011. Inflammation-associated depression: from serotonin to kynurenine. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawson PA, Collins MD, Falsen E, SJoden B, Facklam R. 1999. Facklamia languida sp. nov., isolated from human clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 37:1161–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karpouzas DG, Singh BK. 2006. Microbial degradation of organophosphorus xenobiotics: metabolic pathways and molecular basis. Adv Microb Physiol 51:119–225. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(06)51003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira LA, Chan DSG, Ng TM, Lin R, Jureen R, Fisher DA, Tambyah PA. 2009. Pseudo-outbreak of Rhizobium radiobacter infection resulting from laboratory contamination of saline solution. J Clin Microbiol 47:2256–2259. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02165-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreau-Gaudry V, Chiquet C, Boisset S, Croize J, Benito Y, Cornut PL, Bron A, Vandenesch F, Maurin M. 2012. Three cases of post-cataract surgery endophthalmitis due to Rhizobium (Agrobacterium) radiobacter. J Clin Microbiol 50:1487–1490. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06106-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.da Silva SM, Venceslau SS, Fernandes CLV, Valente FMA, Pereira IAC. 2008. Hydrogen as an energy source for the human pathogen Bilophila wadsworthia. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 93:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s10482-007-9215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonough JH Jr, Shih TM. 1997. Neuropharmacological mechanisms of nerve agent-induced seizure and neuropathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 21:559–579. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(96)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savitz J, Dantzer R, Wurfel BE, Victor TA, Ford BN, Bodurka J, Bellgowan PSF, Teague TK, Drevets WC. 2015. Neuroprotective kynurenine metabolite indices are abnormally reduced and positively associated with hippocampal and amygdalar volume in bipolar disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 52:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savitz J, Drevets WC, Smith CM, Victor TA, Wurfel BE, Bellgowan PSF, Bodurka J, Teague TK, Dantzer R. 2015. Putative neuroprotective and neurotoxic kynurenine pathway metabolites are associated with hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in subjects with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 40:463–471. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farias S, Frey LC, Murphy RC, Heidenreich KA. 2009. Injury-related production of cysteinyl leukotrienes contributes to brain damage following experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 26:1977–1986. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raithel M, Zopf Y, Kimpel S, Naegel A, Molderings G, Buchwald F, Schultis H, Kressel J, Hahn E, Konturek P. 2011. The measurement of leukotrienes in urine as diagnostic option in systemic mastocytosis. J Physiol Pharmacol 62:469–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu CY, Robinson CP. 1988. The effects of soman on norepinephrine uptake, release, and metabolism. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 96:185–190. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(88)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bizzarri C, Pedicelli S, Cappa M, Cianfarani S. 2016. Water balance and ‘salt wasting’ in the first year of life: the role of aldosterone-signaling defects. Horm Res Paediatr 86:143–153. doi: 10.1159/000449057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernardi S, Toffoli B, Zennaro C, Bossi F, Losurdo P, Michelli A, Carretta R, Mulatero P, Fallo F, Veglio F, Fabris B. 2015. Aldosterone effects on glomerular structure and function. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 16:730–738. doi: 10.1177/1470320315595568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka H, Sirich TL, Meyer TW. 2015. Uremic solutes produced by colon microbes. Blood Purif 40:306–311. doi: 10.1159/000441578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka H, Sirich TL, Plummer NS, Weaver DS, Meyer TW. 2015. An enlarged profile of uremic solutes. PLoS One 10:e0135657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer TW, Hostetter TH. 2012. Uremic solutes from colon microbes. Kidney Int 81:949–954. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schultz MK, Wright LKM, Furtado MD, Stone MF, Moffett MC, Kelley NR, Bourne AR, Lumeh WZ, Schultz CR, Schwartz JE, Lumley LA. 2014. Caramiphen edisylate as adjunct to standard therapy attenuates soman-induced seizures and cognitive deficits in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol 44:89–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Araujo Furtado M, Lumley LA, Robison C, Tong LC, Lichtenstein S, Yourick DL. 2010. Spontaneous recurrent seizures after status epilepticus induced by soman in Sprague-Dawley rats. Epilepsia 51:1503–1510. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, Glockner FO. 2013. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e1. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Tumbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, Andersen GL, Knight R, Hugenholtz P. 2012. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J 6:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R. 2010. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26:266–267. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. 2007. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. 2013. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, Clemente JC, Burkepile DE, Thurber RLV, Knight R, Beiko RG, Huttenhower C. 2013. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol 31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tyburski JB, Patterson AD, Krausz KW, Slavik J, Fornace AJ Jr, Gonzalez FJ, Idle JR. 2009. Radiation metabolomics. 2. Dose- and time-dependent urinary excretion of deaminated purines and pyrimidines after sublethal gamma-radiation exposure in mice. Radiat Res 172:42–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patterson AD, Maurhofer O, Beyoglu D, Lanz C, Krausz KW, Pabst T, Gonzalez FJ, Dufour JF, Idle JR. 2011. Aberrant lipid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma revealed by plasma metabolomics and lipid profiling. Cancer Res 71:6590–6600. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li F, Patterson AD, Krausz KW, Tanaka N, Gonzalez FJ. 2012. Metabolomics reveals an essential role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) in bile acid homeostasis. J Lipid Res 53:1625–1635. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M027433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tyburski JB, Patterson AD, Krausz KW, Slavik J, Fornace AJ Jr, Gonzalez FJ, Idle JR. 2008. Radiation metabolomics. 1. Identification of minimally invasive urine biomarkers for gamma-radiation exposure in mice. Radiat Res 170:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bylesjö M, Rantalainen M, Cloarec O, Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Trygg J. 2006. OPLS discriminant analysis: combining the strengths of PLS-DA and SIMCA classification. J Chemom 20:341–351. doi: 10.1002/cem.1006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith CA, Want EJ, O'Maille G, Abagyan R, Siuzdak G. 2006. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal Chem 78:779–787. doi: 10.1021/ac051437y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and analyzed during this study are included in the published article and the supplemental material files, with the exception of raw urine mass spectrometry and 75-day microbiome assay data, which are available from M. Jett upon request.