Abstract

Pain-sensing sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) can become sensitized (hyperexcitable) in response to surgically-induced peripheral tissue injury. However, the potential role and molecular mechanisms of nociceptive ion channel dysregulation in acute pain conditions such as those resulting from skin and soft tissue incision remain unknown. Here, we use selective pharmacology, electrophysiology and mouse genetics to link observed increased current densities arising from Cav3.2 isoform of T-type calcium channels (T-channels) to nociceptive sensitization using a clinically-relevant rodent model of skin and deep tissue incision. Furthermore, knockdown of the Cav3.2-targeting deubiquitinating enzyme USP5, or the specific disruption of its binding to Cav3.2 channel, in peripheral nociceptors resulted in a robust antihyperalgesic effect in vivo, and substantial T-current reduction in vitro. Our study provides a key mechanistic understanding of Cav3.2 channel’s plasticity post-surgical incision and identifies novel therapies for perioperative pain that may greatly decrease the need for narcotics and potential for drug abuse.

One Sentence Summary:

Selective pharmacological antagonism of Cav3.2 channels in peripheral nociceptors and disruption of Cav3.2-USP5 signaling alleviate hyperalgesia post-surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Although opioids are very effective in treating the acute pain associated with surgical procedures, their use is associated with serious side effects, which include constipation, urinary retention, impaired cognitive function, respiratory depression, tolerance, and addiction (1,2). More than 12 million people in the United States abused prescription opioids in 2010 alone (3), resulting in more overdose deaths than heroin and cocaine combined (4). The necessity to treat this acute type of pain is of paramount importance since its duration and intensity influence the recovery process after surgery, as well as the onset of chronic post-surgical pain (5). Despite the use of several other groups of drugs as adjuvants (such as NMDA-antagonists, gabapentinoids, acetaminophen, alpha-2 adrenergic agonists), there is a recognized need for developing novel therapeutic agents that could improve outcomes of conventional treatment of post-surgical pain in clinical settings while avoiding dangerous side effects.

A growing body of evidence suggests an important role of the Cav3.2 isoform of T-type calcium channels (T-channels) in neuronal transmission of painful stimuli in both physiological and pathological states (6-10). The majority of these studies are focused on chronic neuropathic pain; however, little is known about potential role of T-channels in the development and maintenance of acute pain and hypersensitivity after surgery. Here, we use an experimental pain model described as plantar incision of the hind paw in rodents (11,12). This model exhibits both thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity with primary and secondary hyperalgesia (13), characteristic for human post-operative pain. Our study reveals that the excitability of nociceptive neurons of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) is increased in the immediate post-surgical period, along with T-channel current density, largely due to deubiquitination of the channel. Furthermore, using both pharmacological and molecular tools, we show that nociception can be alleviated by selectively inhibiting Cav3.2 T-channels, thus establishing this channel as a promising therapeutic target for acute pain treatment post-surgery.

RESULTS

Development of incisional pain

To determine the time-course of the development of post-surgical pain, we performed paw incision surgeries on rats as previously described (11) and monitored them up to seven days using evoked pain tests of thermal nociception (fig. S1A) and mechanical hypersensitivity (fig. S1B). The development of thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia was recognized as a reduction of thermal paw withdrawal latencies (PWL) or thresholds for mechanical paw withdrawal responses (PWR) by approximately 65% from pre-incision values. Indeed, a statistically significant reduction in thermal PWLs was noticed during 6 days post-incision, and during 5 post-surgery days in mechanical PWR testing. Almost complete recovery of paw responses to pre-surgery values was achieved around day 7. This finding is consistent with previous reports of the development of thermal and mechanical post-surgical hyperalgesia in rodents (11,14,15). Since the most profound hyperalgesia was detected at 24 and 48 hours post-incision, subsequent in vitro and in vivo experiments were performed during that timeframe (boxed area on fig. s1A and fig. s1B).

Post-surgical hyperalgesia is associated with an increase in T-current density in acutely dissociated DRG rat sensory neurons

Several previous studies investigate the role of T-currents in chronic pain states (7); however, their role in acute post-surgical pain remains to be elucidated. Since voltage-dependent activation and inactivation can influence excitability of T-channel-expressing neurons, we first studied the effect of incision on these biophysical properties in DRG cells.

We used sham operated animals (exposed to anesthesia without surgery), and incised animals (exposed to anesthesia with surgery) at 24 h and 48 h post-procedure. Recordings were made from small to medium size DRG neurons (less than 35 μm soma diameter) since they are likely nociceptors and express prominent T-currents (16,17). To determine the expression of T-currents in DRG neurons, we set holding potentials (Vh) to −90 mV and then depolarized to test potentials (Vt) from −75 to −30 mV in 5 mV increments. Representative traces of inward currents for sham and post-incision cells are depicted in Fig. 1A with a crisscrossing pattern typical for T-channels. From I-V relationships, we found that average peak T-current densities were increased more than two-fold in the post-incision group compared with the sham group over the range of test potentials (Fig. 1B). We also measured time-dependent activation (10%-90% rise time, Fig. 1C), as well as time-dependent inactivation constant (τ) in these cells (Fig. 1D). Although rise times between sham and post-incision groups were not significantly different, we found that time-dependent inactivation after surgery was increased approximately two-fold, as compared to the sham group. To independently assess the effects of post-operative pain on T-current density we used our regular steady-state inactivation protocols. Fig. 1E depicts representative traces of evoked T-currents after 3.5 second-long prepulses at different conditioning potentials. Again, our analysis revealed that T-current densities measured in sensory neurons post-incision were significantly increased (about two-fold) when compared to shams at the range of conditioning potentials (Fig. 1F).

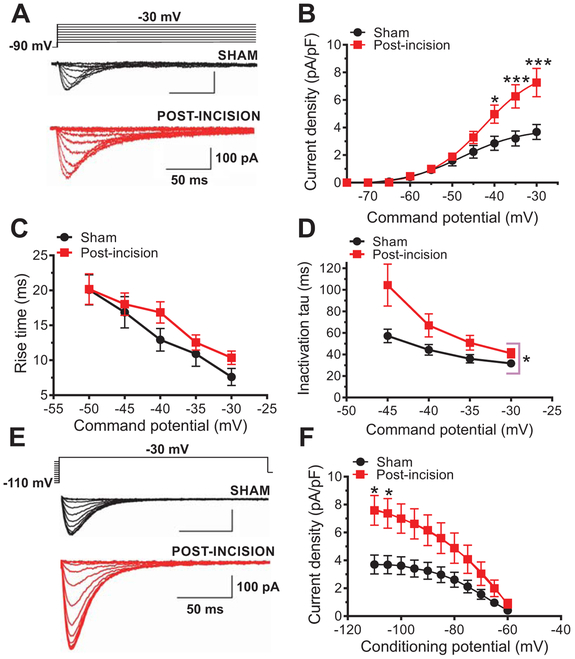

Fig. 1. Effects of plantar skin incision on T-current kinetics and density in rat DRG cells.

A. Families of T-currents evoked in representative DRG cells from sham and incised rats were used to generate current-voltage (I-V) relationships. B. Average peak T-current densities calculated from I-V curves were increased more than two-fold in the post-incision group (n=20 cells, 10 animals) compared with the sham group (n=14 cells, 10 animals) (***P<0.001, *P<0.05 two-way RM-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-hoc test; treatment: F(1,32)=5.52, p=0.02; interaction: F(9,288)=6.72, post-hoc: p=0.017 and p<0.001). C. Time-dependent activation (10-90 % rise time) measured from I-V curves in DRG cells was not significantly affected by plantar skin incision (n=14 cells from 10 sham animals; n=20 cels from 10 animals post-incision; two-way RM-ANOVA; p=0.3). D. Inactivation time constant measured from I-V curves was significantly slower approximately two-fold after plantar skin incision (n=14 cells, 10 sham animals; n=20 cells, 10 animals post-incision; *P<0.05 two-way RM-ANOVA, treatment: F(1,32)=4.33, p=0.04; interaction: F(3, 96)=2.36, p=0.08). E. Families of T-currents evoked in representative DRG cells by steady-state inactivation protocols in sham (back traces) and incised (red traces) groups. F. T-current densities from steady-state inactivation curves post-incision (n=21 cells, 10 animals) were significantly increased when compared to sham (n=14 cells, 10 animals) (two-way RM-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-hoc test; interaction: F(10, 330)=6.78, p<0.0001; post hoc: p=0.026, p=0.041; treatment: F(1,33)=4.15, p=0.049).

In contrast, very little difference was found in midpoint values (V50) for voltage-dependent steady-state activation (fig. S2A), steady-state inactivation curves (fig. S2B) and deactivation time constant (fig. S2C) between the post-incision group and sham controls.

Taken together, increased T-current densities may suggest that more T-channels were activated post-incision compared to the sham group, perhaps due to their increased expression, and/or due to the change in biophysical properties indicative of increased channel activity.

Plantar skin incision increases high frequency firing and excitability of DRG sensory neurons

Next, we used the current-clamp technique to monitor firing patterns of DRG neurons and to examine if T-channels may be involved in the changes in intrinsic excitability of sensory neurons from lumbar DRGs after incision. After application of 3 μM TTA-P2 (3,5-dichloro-N-[1-(2,2-dimethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-4-ylmethyl)-4-fluoro-piperidin-4-ylmethyl]-benzamide), which selectively blocks T-currents in DRG cells (18), we noticed a profound decrease in the number of action potentials (APs) post-incision in the range of current injections from 0 to 50 pA, as compared to the baseline measurements (Fig. 2A and 2B). When we analyzed firing patterns of the recorded cells in sham versus post-incision cohorts we were able to identify three distinct types of neurons based on their frequency of APs firing: single, multiple and high frequency spiking cells (Fig. 2C). Single spiking cells fired only one AP through the range of current injections. Multiple spiking cells were defined as cells firing at least 3 APs with frequencies less than 45 Hz, while high frequency spiking cells had AP firing frequency above this threshold. Recordings from post-incision cells showed that the number of high-frequency firing cells post-incision was about 4-fold higher when compared to the sham group (Fig. 2D).

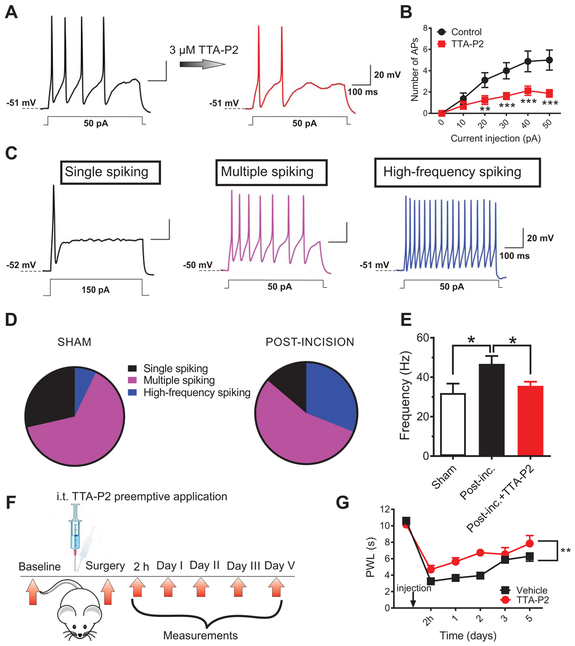

Fig. 2. T-channels contribute to cellular hyperexcitability of sensory neurons after incision.

A. Representative traces of action potentials (APs) in a DRG cell treated with a T-type channel blocker (TTA-P2) from post-incision group (current injection of 50 pA) before and after application of 3 μM TTA-P2. B. Number of action potentials post-incision before and after application of TTA-P2; n=8 cells per group from 6 animals; each data point represents mean ±SEM, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-way RM-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-hoc; interaction: F(5,35)=6.69, p<0.001; post-hoc: p=0.002, p<0.001, p<0.001 and p<0.001 for current injections 20, 30, 40 and 50 pA, respectively; treatment: F(1,7)=14.72, p=0.006).

C. Representative traces from single-, multiple- and high frequency-spiking DRG cells. D. The pie charts show the distribution of different types of firing patterns of DRG cells post-incision and in the sham groups respectively; post-incision group: n=29 cells, 8 animals); sham group: n=28 cells, 8 animals; (Fisher’s exact test p=0.04. E. Bar graphs represents frequency of AP firing in sham group (white bar), untreated post-incision group (black bar) and in post-incision group incubated with TTA-P2 for 5-10 minutes (red bar); n=13 cells from 5 animals in sham; 15 cells from 7 animals in untreated post-incision and 8 cells from 2 animals in post-incision+ TTA-P2 group respectively; *P<0.05, Unpaired t-test, p=0.02). The data is expressed as mean±SEM. F. A time-course of the in vivo experiment. G. Preemptive i.t. application of TTA-P2 significantly attenuated thermal hyperalgesia post-incision as evidenced by prolonged thermal paw withdrawal latency (PWL) (n=8 animals per group; **P< 0.01, two-way RM-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-hoc test; interaction: F(4,56)=1.16; p=0.3; treatment: F(1,14)=17.61; p=0.001)as compared to the vehicle group. The data is expressed as mean ±SEM.

To investigate a possible role of T-channels in excitabiity of DRG neurons post-surgery, we recorded firing frequencies of the first three APs in three groups –sham (S), post-incision (PI) and post-incision group incubated with 3 μM TTA-P2 (PI+TTA-P2). Figure 2E summarizes these results and shows that the average firing frequency of APs was increased in PI group about 45% when compared to the S group. Furthermore, in PI+TTA-P2 group, the average frequency of firing was significantly reduced as compared to the PI group and was not statistically different from the sham group (Fig. 2E). In order to make appropriate comparisons of excitability, we held the resting membrane potentials (RMP) at very similar values (e.g. S: −51.8±1.1 mV; PI: −52.8±0.9 mV). Likewise, the input resistance was not significantly different between the sham (1027±237 MΩ) and post-incision groups (1013±329 MΩ). Hence, observed increase in neuronal excitability in incised animals vs. sham group are not due to alterations in pasive membrane properties.

Most of the T-channel expressing DRG cells in our study likely belong to a group of unmyelinated C-polymodal nociceptors sensitive to different noxious stimuli, including noxious heat (16,17). Hence, we applied TTA-P2 intrathecally (i.t.) in vivo before surgical incision in rats (preemptive application, Fig. 2F) and measured their response to noxious thermal (heat) stimuli. Applied in a single intrathecal dose of 215.5 μg determined from experiments in healthy rats as the highest effective dose (fig. S3), TTA-P2 significantly decreased nociceptive response to heat stimulus in incised rats, during 5 days of post-operative follow-up (as compared to the vehicle-treated group, Fig. 2G). Interestingly, a group of animals that received TTA-P2 i.t. immediately before surgery, had a very fast onset of the reduction of heat nociception (at 2 h post-surgery) that persisted for the next two days, as compared to the vehicle-injected group. A significant anti-nociceptive effect of preemptive TTA-P2 was still noticeable on day 5, indicating that preemptive application of TTA-P2 successfully reduces thermal nociception; however, it did not increase the rate of recovery. Collectively, these data strongly suggest that T-channels are heavily involved in increased excitability of nociceptive sensory neurons and in transmission of noxious heat stimuli after the incision.

Repetitive intrathecal application of TTA-P2 in vivo alleviates post-incision pain in rats

To further investigate the functional consequence of blockade of T-channels in vivo, we first applied TTA-P2 i.t. in unoperated animals, and recorded responses evoked by thermal and mechanical stimuli (fig. S3A). We observed that TTA-P2 substantially reduced thermal (fig. S3B) and mechanical (fig. S3C) responses in unoperated animals in a dose-dependent manner compared to the vehicle-treated group. To examine whether antinociceptive effect of TTA-P2 could be due to its non-specific effects such as sedation and/or motor weakness, we performed a battery of sensorimotor tests. The responses after treatment with TTA-P2 in these animals did not differ from those responses before injection in any of these tests (both pre and post-drug time that animals spent on inclined screen and elevated platform was 120 s; animals were able to walk the plank in two separate trials for 60 s before and after the drug injection, fig. S3D, E and F).

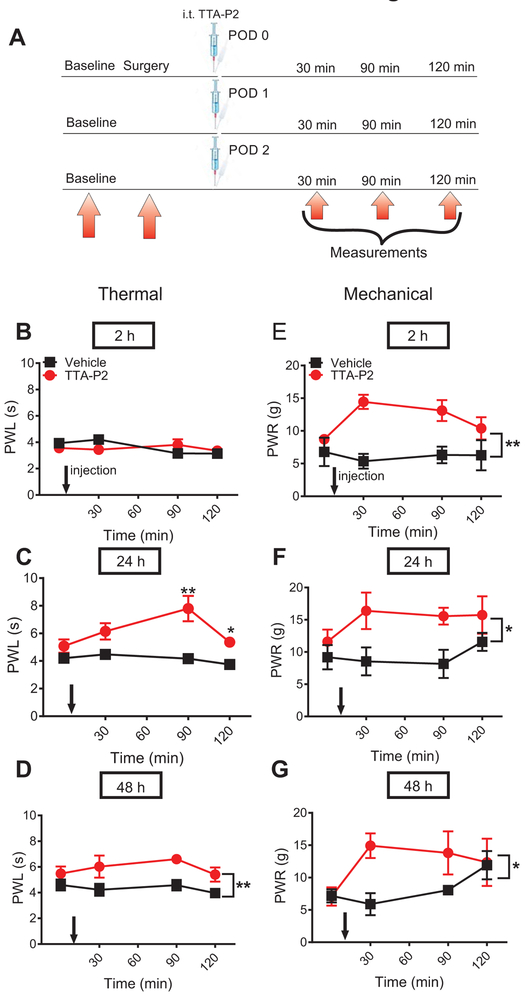

In our next set of experiments, we investigated the anti-nociceptive effect of TTA-P2 injected i.t. repeatedly at 2, 24 and 48 h post-incision (Fig. 3A). We chose this particular dosing regimen because neuroaxial application of analgesic drugs during the first 48 hours of a post-operative period is an established and safe practice in humans (19,20). Either test compound or vehicle was applied in one group of animals. Although there was no effect on heat nociception after the first dose of TTA-P2 applied 2 h post-incision (Fig. 3B), we found a significant alleviation of heat nociception when TTA-P2 was applied 24 and 48 h post-surgery (Fig. 3C and 3D). The most prominent antinociceptive effect in heat nociception testing was achieved 90 minutes post-injection, as measured 24 h after the incision; after the third application 48h post-incision, the antinociceptive effect was steadily present up to 90 minutes post-injection. Notably, repeated i.t. application of TTA-P2 alleviated mechanical hypersensitivity at 2, 24 and 48 h after three consecutive applications, as measured up to 120 minutes post-injection (Fig. 3E, 3F and 3G). Thus, our data indicate that selective blockade of T-channels leads to alleviation of thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity and that there is no apparent tolerance after repeated applications of TTA-P2 in vivo. The lack of effect of TTA-P2 on thermal nociception 2 h post-surgery could indicate that T-channels are not involved in the development but rather in maintenance of thermal hyperalgesia. In contrast, we found that TTA-P2 was effective in alleviating mechanical hypersensitivity as early as 2 h post-surgery suggesting that T-channels likely play a role in both development and maintenance of mechanical hyperalgesia post-incision.

Fig. 3. Repeated application of TTA-P2 alleviates thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity post-incision.

A. Time course showing pre-surgical baseline measurements to heat and mechanical stimuli determined two days before surgery, 2 h post-incision, and on two consecutive days, prior to intrathecal treatment (i.t.) injections. Heat and mechanical hypersensitivity was assessed 30, 60 and 120 min after TTA-P2 or vehicle was applied i.t. in a single group of animals. B. Lack of the antinociceptive effect of the first dose of TTA-P2 applied 2 h after plantar skin incision on heat nociception (n=6 animals in vehicle and n=10 animals in treatment group; two-way RM-ANOVA). C and D respectively, Significant antinocicpetive effects of consecutive doses applied at 24 and 48 h post-incision, on heat nociception; n=6 animals in vehicle groups and n=9 animals in treatment groups * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, Mann-Whitney test; repeated treatment 24 h post-incision: p=0.003 and p=0.026; two-way RM-ANOVA, repeated treatment 48 h post-incision: F(1,13)=9.75; p=0.008; interaction: p=0.8). E, F and G respectively, Significant antinociceptive effect of repeated i.t. application of TTA-P2 on mechanical hypersensitivity 2, 24 and 48 h post-(; n=6 animals in vehicle group and n-5-6 animals per post-incision group; * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, two-way RM-ANOVA; repeated treatment 2 h post-incision: F(1,10)=19.7; p=0.001; repeated treatment 24 h post-incision: F(1,10)=8.73; p=0.014; repeated treatment 48 h post-incision: F(1,9)=7.08; p=0.026). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM for incised paw. PWL = paw withdrawal latency; PWR = paw withdrawal response.

Plantar skin incision increases the membrane fraction of Cav3.2 channels

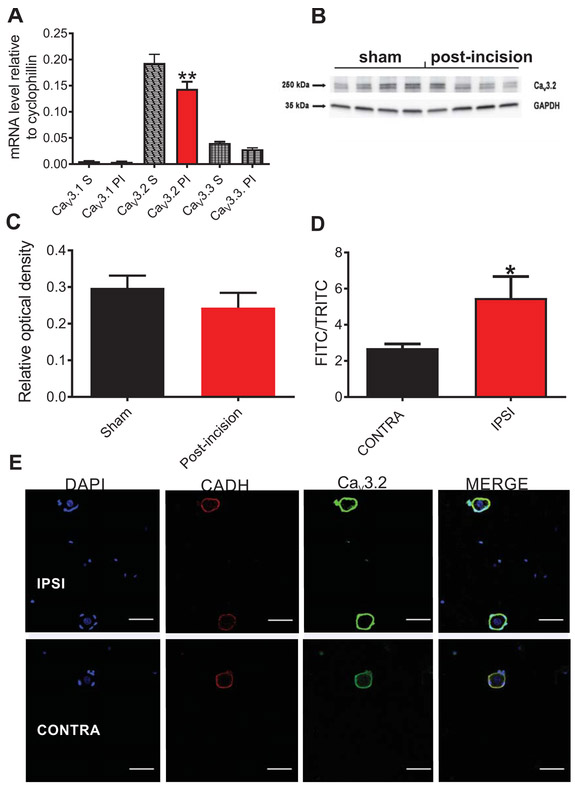

To further elucidate whether there was an increased expression of T-channels that could explain incresad current densities, we performed qRT-PCR analysis of all three T-type channel isoforms (Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3) post-sham or post-incision at 24 h and 48 h after surgery in L4-L6 unilaterally harvested DRGs. As expected, qRT–PCR analysis of mRNA expression in sham rats revealed that the Cav3.2 isoform had the highest levels of mRNA compared to the two other isoforms, which is in accordance with previously published data using in-situ hybridization (21). Surprisingly, mRNA levels of the Cav3.2 isoform after incision was moderately decreased (by about 25%) compared to the sham group (Fig. 4A). To determine if total Cav3.2 protein expression was changed, we performed Western blotting of the DRG tissue from sham and post-incision rats. We found that total protein levels of Cav3.2 in lumbar DRG tissues in post-incision group were similar to the sham group (Fig. 4B and 4C). Since both qRT-PCR and immunoblotting methods could not explain the increased T-current densities in DRG cells (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that the membrane fraction of Cav3.2 channel in DRG cells may be increased post-incision. Hence, we performed immunostaining of acutely dissociated sensory neurons (<35 μm diameter) at 48 h post-incision from ipsilateral and contralateral DRGs of incised rats using a Cav3.2-specific antibody and an antibody against cadherin (CADH), a structural membrane protein (Fig. 4D,E). In order to determine if there are any changes in the membrane expression of Cav3.2 channel post-incision, we compared the fluorescence intensities of anti-Cav3.2 antibody normalized to anti-pan-cadherin fluorescence. Our results indicate that the normalized fluorescence of anti-Cav3.2 antibody is significantly increased (about two-fold) in the ipsilateral DRG cells from incised rats when compared to the contralateral DRG cells (Fig. 4D). These data strongly suggest that the membrane fraction of Cav3.2 channels is increased in ipsilateral DRG sensory neurons after incision despite the unchanged total levels of Cav3.2 protein (as suggested by our Western blot experiments).

Fig. 4. Membrane expression of Cav3.2 channels in rat DRG cells is increased after plantar skin incision.

A. mRNA levels of three isoforms of T-channels (Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3) post-incision (24 h and 48 h after the surgery; n=4 samples, each sample contained pulled L4-L6 unilaterally harvested DRGs from 7 animals, total of 28 animals) and in sham group (n=4 samples, each sample contained pulled L4-L6 DRGs harvested from 4 animals, total of 16 animals). The data is obtained from at least three independent experiments, and represented as mean± SEM; **P<0.01, Ordinary One-way ANOVA; surgery treatment: F(5,66)=83.04, p=0.002. B. Representative blot image of Cav3.2 isoform of T-channel in DRG homogenate; n=4 samples of L4-L6 DRG tissue pooled from 12 animals for incision group, and n=4 samples of L4-L6 DRG tissue pooled from 8 animals post-incision. C. Bar graph represents total protein levels of Cav3.2 isoform of T-channel in DRG homogenates after incision (red bar), and in sham group (black bar). The data is obtained from 4 samples in post-incision group, where each sample contains L4-L6 DRGs from 3 animals, and from 4 samples in sham group, where each sample contains L4-L6 DRGs from 2 animals. The data is expressed as mean ±SEM. No significant difference was found between the groups (Mann Whitney test). D. Relative level of expression of Cav3.2 immunofluorescense normalized to pan-cadherin (CADH) 48 h post-incision in ipsilateral and contralateral rat DRG sensory neurons (n=32-33 cells per each group, harvested from 4 animals in four independent experiments. *P<0.05, unpaired t-test, p=0.022. E. Representative images of ipsilateral and contralateral rat DRG sensory neurons 48 h post-incision: the images show membrane fluorescence of Cav3.2 (green color) and pan-cadherin (red color) antibodies. DAPI (blue color) shows the nuclei of cells. Scale bar length is 50 μm.

Hence, we reasoned that the increase in the membrane fraction of Cav3.2 channels post-incision may contribute to the observed increase in T-current densities (Fig. 1) and hyperexcitability of DRG cells (Fig. 2D,E).

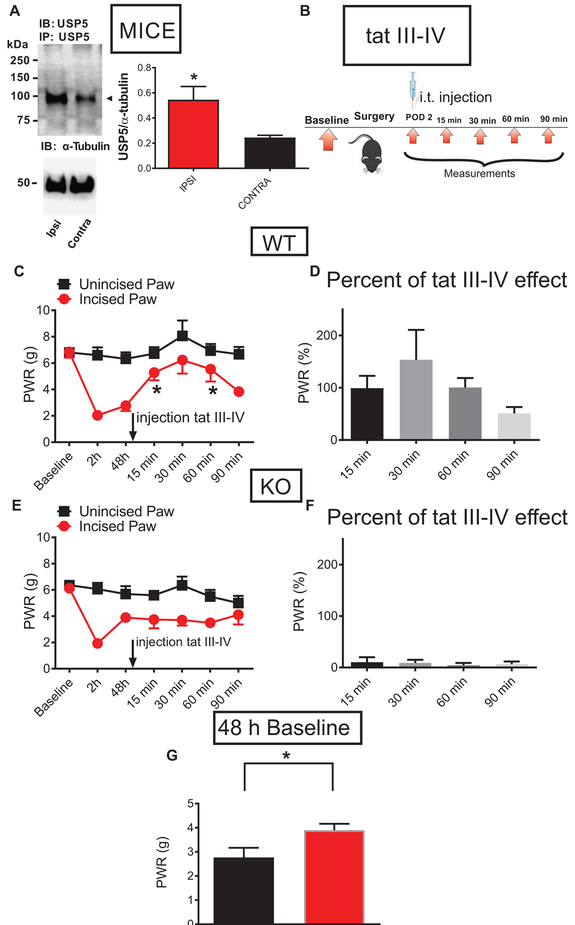

Selective knockdown of deubiquitination of Cav3.2 channels in nociceptors prevents the development of mechanical hypersensitivity in mice after plantar skin incision

Since our recent study strongly implicated the deubiquitinating enzyme, ubiquitin-specific protease 5 (USP5) as a specific Cav3.2 interacting partner (22), we next investigated the role of Cav3.2 channel ubiquitination in the setting of surgical tissue injury using wild-type (WT) and Cav3.2 knock-out (KO) mice. For these studies we used i.t. application of USP5-shRNA to knockdown USP5 in mouse DRGs in vivo. The potency and specificity of this USP5-shRNA construct to reduce USP5 levels and mediate analgesia in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models was previously established (22).

Other studies have established that hyperalgesia in WT mice following surgical paw incision largely mirrors the same time course like in WT rats with the maximal hyperalgesia at post-operative day (POD) 1 and 2 (23). Hence, we have limited our mechanistic studies in mice to POD 1 and 2. First, we performed immunoblotting to investigate if the expression of USP5 may be altered in ipsilateral lumbar DRGs of wild type (WT) mice post-incision. Indeed, our immunoblotting data confirmed that USP5 protein levels are increased aproximately 3-fold in ipsilateral, as compared to the contralateral DRG cells in WT mice post-incision (Fig. 5A). Next, we investigated the interaction between USP5 and Cav3.2 in vivo by measuring thresholds for paw withdrawal responses (PWR) to a punctate stimulus before surgery (baseline) and at Day 1 post-incision (fig. S4A). As expected, we found prominent mechanical hypersensitivity in WT mice that received vehicle treatments preemptively as indicated by decreased thresholds for PWRs (fig. S4B). In contrast, preemptive application of USP5-shRNA 24 h before incision significantly suppressed this nociceptive behavior as indicated by significantly higher thresholds for PWRs when compared to the vehicle treatments in ipsilateral paws in WT mice (fig. S4B). In contrast, PWRs in contralateral, unoperated paws remained stable. To further confirm the selectivity of USP5 interaction with Cav3.2, we also included Cav3.2 KO animals in our experiment (fig. S4C,D). Our results show that after incision, mechanical sensitivity to a punctate stimulus was not significnaly different between the untreated Cav3.2 KO group and the Cav3.2 KO group that preemptively received USP5-shRNA (fig. S4C). Furthermore, when we compared PWRs on Day 1 post-incision in two cohorts in ipsilateral paws, we noticed significantly less mechanical hypersensitivity in the KO group, as compared to the WT group (fig. S4D). This argues that Cav3.2 channels are required for the antihyperalgesic effect of USP5-shRNA and that Cav3.2 channels are important for the observed mechanical hyperalgesia induced by surgical paw incision in WT mice.

Fig. 5. Selective targeting of deubiquitination of Cav3.2 channels in nociceptors prevents the development of mechanical hypersensitivity in mice after plantar skin incision.

A. Representative Western blotting of three independent experiments of immunoprecipitated USP5 from DRG homogenates from ipsilateral and contralateral L4-L6 DRGs from WT mice post-incision, and a bar graph of the relative expression levels of USP5 48 h post-incision; n=3 animals: tissue homogenates of L4- L6 DRGs were harvested separately from ipsi and contralateral side of the spinal column and WB was performed in three animals, *P<0.05, Unpaired t-test; p=0.047. B. A time-course of in vivo experiment: 48 h post-surgery, WT and Cav3.2 KO mice were injected i.t. with tat III-IV peptide and PWRs were measured 15, 30, 60 and 90 minutes post-injection. C. The antihyperalgesic effect of injected tat III-IV peptide on PWR thresholds of incised paws in WT mice as measured 15, 30, 60 and 90 minutes post-injection. n=6 animals per group, *P<0.05, RM One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test; p=0.040. D. Robust antihyperalgesic effect of injected tat III-IV peptide on incised paws in WT mice was normalized to the pre-injection baseline (the same data as in panel C of this figure). E. Injected tat III-IV peptide did not significantly alter the PWR in incised paws of the Cav3.2 KO animals; n=6 animals per group, RM One-way ANOVA; p=0.754. F. The lack of effect of injected tat III-IV peptide on PWR thresholds of incised paws in Cav3.2 KO mice was normalized to the pre-injection baseline (the same data as in panel E of this figure). G. The difference between mechanical sensitivity thresholds recorded 48 h post-incision in WT (black bar) and Cav3.2 KO (red bar) mice; *P<0.05, n=6 animals per group, Unpaired t-test, p=0.04.

Finally, to confirm that the antinociceptive effect of USP5-shRNA appears as a consequence of the specific interaction of the Cav3.2 channel with USP5, we tested the effects of a selective tat peptide. This peptide corresponds to the intracellular domain III-IV linker region of the Cav3.2 channel which is recognized as a binding site for USP5 (22). The specificity and selectivity of this reagent was confirmed previously in our study which showed that a tat-Cav3.2-CT peptide (corresponding to the C terminus of Cav3.2), and a tat-free Cav3.2 III-IV linker peptide did not exhibit any effect in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models (22). Figure 5B shows time courses of our experiments with tat III-IV peptide. When injected intrathecally 48 hours post-incision, tat III-IV peptide (10 μg/i.t.) relieved mechanical hypersensitivity as evident by an increased threshold for PWRs in ipsilateral paws in WT, but not in Cav3.2 KO mice (Fig. 5C and 5E, respectively). When the data were expressed as the percentage of antihyperalgesic effect normalized to the pre-injection baseline, the tat III-IV peptide achieved almost complete reversal of the response to mechanical stimuli 15-60 minutes post-injection in WT, but not in KO mice, as shown in Fig. 5D and 5F, respectively. We also analyzed the pre-injection baseline values to mechanical stimulus 48 h post-surgery in WT and KO mice. This revealed that the mechanical hypersensitivity in WT mice is significantly lower than in KO mice, suggesting that the onset of recovery in KO begins earlier as compared to the WT mice, further indicating a prominent role of Cav3.2 channels in this pain model (Fig. 5G). Time course of mechanical anti-hyperalgesia after i.t. administration of tat III-IV peptide in our experiments with paw incision corresponds well to its reported effects using other pain models in WT mice (22).

Overall, our findings strongly support the idea that the development and maintenance of mechanical hypersensitivity post-surgery is, at least in part, mediated by deubiquitination of the Cav3.2 protein, which likely leads to its increased membrane stability. Therefore, the Cav3.2 channel in peripheral nociceptors is required as a key mediator of analgesic effects of USP5-shRNA in WT mice after paw skin incision. On the other hand, the apparent lack of antinociceptive effect of USP5-shRNA and tat III-IV peptide in Cav3.2 KO mice clearly indicates that USP5-dependent deubiquitination is highly specific for Cav3.2 channels, making this interaction very unique and important for the development of pain after surgery.

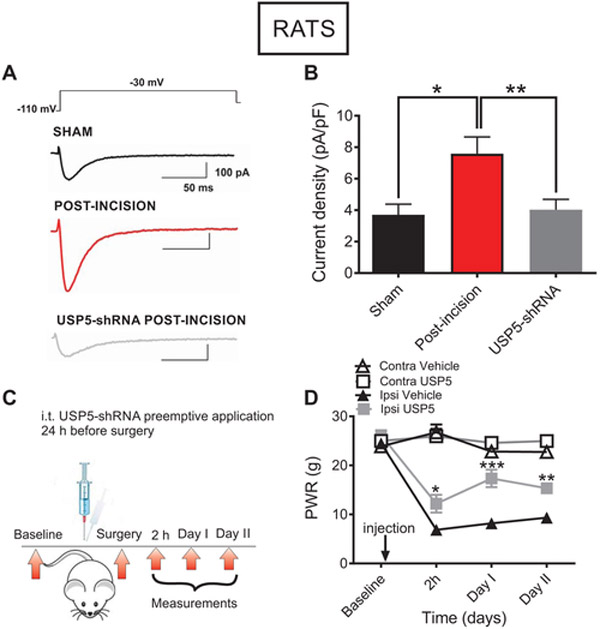

Preventing the deubiquitination of Cav3.2 channels in nociceptors reduces T-current density and diminished mechanical hypersensitivity after plantar skin incision in rats

To test in vitro effects of the disruption of Cav3.2 channels deubiquitination, we recorded T-currents in putative rat DRG nociceptors 24 or 48 h post-surgery using the same protocol as described in Figure 1. In these experiments we compared T-current densities from DRG cells in the sham group of rats, in rats that received i.t. injections of USP5-shRNA (12.5 μg/i.t.) 24 hours before plantar incision and untreated rats that received only plantar incision. Representative traces from these recordings show decreased T-current amplitudes recorded from animals that received USP5-shRNA, as compared to the untreated post-incision group (Fig. 6A). The bar graph of Figure 6B shows average data from multiple experiments and indicates that i.t. applications of USP5-shRNA significantly decreased T-current densities when compared to the cells from incised untreated rats. As the data indicate, T-current density in post-incision group after knocking down USP5 is not significantly different from the sham group (Fig. 6B). Further, we confirmed a successful knockdown of USP5 by measuring thresholds for PWRs in incised rats that received USP5-shRNA i.t. 24 h before incision (Fig. 6C and 6D). Indeed, thresholds for PWRs in ipsilateral paws after injection of USP5-shRNA are significantly higher as compared to the vehicle group at 2 hours, 24 hours (Day I) and 48 hours (Day II) post-surgery, indicating that there is a reduction in mechanical hypersensitivity in incised rats post-treatment. In contrast, contralateral (unincised) paws compared to the ipsilateral paws in the same rats are unaffected with USP5-shRNA treatments (Fig. 6D). Overall, our data strongly suggest that deubiquitination of Cav3.2 channels promotes increase of the T-current densities in nociceptive DRG cells, and implies that this mechanism signifies Cav3.2 channel’s role in the development and maintenance of hyperalgesia after surgical tissue injury in rats and WT mice.

Fig. 6. In vivo silencing of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 reduces T-current densities and mechanical hyperalgesia in rats post-incision.

A. T-currents (Vh −110 mV, Vt −30 mV) in representative DRG cells from the sham (black trace), incised untreated (red trace) and incised animals that were pretreated with USP5-shRNA (gray trace) groups. B. T-current densities in sham animals (balck bar), 48 h post-incision untreated group (red bar), and 48 h post-incision group that received i.t. injection of USP5-shRNA 24 h before plantar incision (gray bar); n=25 cells from 5 animals in USP5 group, n=21 cells from 10 animals in untreated incised group, n=14 cells from 10 animals in sham group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, Ordinary one-way ANOVA, p=0.012 and p=0.007, respectively. Each data point represents mean ±SEM. C. A time-course of the in vivo experiment: baseline PWRs were measured during two days before surgery. One day before surgery, shRNA-USP5 was injected i.t. in rats. After surgery, baseline paw responses to mechanical stimulus were measured at 2 h, as well as on Days I and II post-incision. D. Mechanical hypersensitivity to a punctate stimulus after plantar incision in rats with selective knockdown of USP5, and in the vehicle group (n=7-8 animals per group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-way RM-ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-hoc test: 2 h post-incision (p=0.014), Day I post-incision (p<0.001); Day II post-incision (p=0.004). Each data point represents the average thresholds for paw withdrawal response (PWR) ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

T-channels are involved in increased excitability of sensory nociceptive neurons after plantar skin incision

The present study demonstrates for the first time that T-channels play an important role in the development and maintenance of the acute pain post-surgery. Using a clinically-relevant surgical incision model in rodents we show increased current density of T-channels in peripheral nociceptors. Our previous studies have shown a significant increase in current density of the Cav3.2 isoform of T-currents and increased excitability of DRG sensory neurons in animals with painful diabetic neuropathy (10,24,25). In addition, successful alleviation of pain in several other chronic and visceral pain models has been achieved with selective T-channel blockers (26-28), the Cav3.2 subtype in particular.

We showed that T-channel inactivation is somewhat slower in sensory neurons post-incision as compared to the sham group, which could potentially implicate a contribution of high-voltage-activated (HVA) voltage-gated calcium channels. However, slow deactivating tail currents are characteristic of T-currents, and rule out possible contribution of HVA calcium channels that typically display 10-fold faster deactivating currents (29).

We also examined potential changes in excitability of small sensory neurons in rats with post-incisional hyperalgesia since both increased T-current densities and slower T-current inactivation could favor hyperexcitable states. We discovered that after incision, sensory neurons produce APs of higher frequency as compared to the sham group. Also, the number of fast frequency APs was higher after incision as compared to the sham group. We also showed that the selective T-channel blocker TTA-P2, applied directly to dissociated DRG cells, markedly reduces AP frequency after incision. In another set of experiments, we pre-incubated dissociated DRG cells with TTA-P2, and yet again noticed a reduction in frequency of APs after incision. It is important to mention that the frequency of APs after pre-incubation with TTA-P2 was not significantly different from AP firing frequency in sham animals. We note that dissociated DRG neurons were chosen to correlate electrophysiology with immunostaining experiments, and to have the ability to discriminate cells based on their size more reliably than in whole tissue preparations. We acknowledge the possibility that isolated DRG neurons may not behave identically to those in intact tissue preparation. However, our in vitro data are consistent with our in vivo experiments. Indeed, pre-emptive application of TTA-P2 i.t. in incised rats reduced thermal hypersensitivity as compared to the vehicle-injected group, indicating the importance of T-channels in the development of post-surgical nociception. Furthermore, other nociceptive channels such as TTX-resistant Na+ channels also show increased current density post-incision and could work in concert with T-channels to contribute to increased excitability of DRG sensory neurons during the development and maintenance of post-surgical pain (30).

TTA-P2 alleviates post-surgical thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia

Our previous study showed that intraperitoneal injection of TTA-P2 successfully alleviates inflammatory pain in mice, as well as thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain in rats (18). Furthermore, several studies have also confirmed the role of T-channels in various pain models, where other T-channel blockers have been applied either systemically (31) or as an intraplantar local injection (32,33). Our current study reveals for the first time a role of T-channels in an acute post-incisional pain model associated with skin incision based on the fact that TTA-P2, a selective T-channel blocker, successfully alleviates both heat and mechanical hyperalgesia.

TTA-P2 is a pan-selective T-channel blocker that also blocks other two subtypes of T-channels (Cav3.1 and Cav3.3), and not just Cav3.2 isoform of the channel (34). Even though the other two subtypes (Cav3.1 and Cav3.3) are not abundantly expressed in DRGs, intrathecal application of TTA-P2 could block Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3 channels when applied spinally since mRNA for all three isoforms is expressed in pain processing regions of dorsal horn of the spinal cord (21). Nevertheless, our study firmly establishes a role of Cav3.2 channels in post-incisional hyperalgesia, while the possible role of other T-type isoforms remains to be studied.

Our results suggest that T-channels play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of mechanical hyperalgesia post-incision, since TTA-P2 successfully alleviated mechanical hypersensitivity at 2, 24 and 48 h post-surgery. On the other hand, the lack of immediate effect of TTA-P2 at 2 h post-incision in thermal nociception was noticed suggesting that Cav3.2 channels are important for the maintenance but not for the development of thermal hyperalgesia post-surgery. Similar findings have been reported in other studies with incisional pain models in rodents. For example, muscimol, a GABAA agonist, has shown antihyperalgesic effect to thermal stimulus on Day 1 post-surgery, while it was almost without effect on the day of surgery (35). However, in the same study, muscimol successfully alleviated mechanical hyperalgesia on both days. This implies different mechanisms of modulation of thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia post-surgery in at least two unrelated family of nociceptive ion channels. Also, several other studies show that in different pain models, a potential analgesic compound could exert effect in one modality of evoked pain testing, but not in the other (36,37). Finally, it appears that preemptive blocking of T-channels improves recovery when tested for thermal nociception. Taken together, the results from thermal and mechanical in vivo testing strongly suggest that T-channels play an important role not only in maintaining (thermal and mechanical) but also in the development (mechanical) of post-surgical hyperalgesia after skin incision.

Plantar skin incision increases membrane surface expression of Cav3.2 channel isoform

Previous studies have shown an increased expression of Cav3.2 isoform of T-channels in DRGs in different pain disorders such as painful diabetic neuropathy (10) and paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy (38). Surprisingly, our results from qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis of DRG tissues did not support an increase of expression of mRNA or total protein levels of any of three isoforms of T-channels post-incision. However, our immunostaining experiments revealed an increase in membrane fraction of Cav3.2 channels in a specific subpopulation of DRG sensory neurons (small to medium size), which supports our in vitro findings of increased T-current density and hyperexcitability of the nociceptive sensory neurons post-incision. We proposed that observed increase in membrane expression levels of Cav3.2 channels could be related to some other mechanism that contributed to the protein stability in the membrane, rather than an increase in the channel production, as mRNA and protein levels were not enhanced after the surgery.

In vivo silencing of the gene for USP5, a deubiquitination enzyme for Cav3.2 channel isoform, reduced mechanical hyperalgesia and T-current densities in peripheral nociceptors

Previously published data established that the Cav3.2 channel is a predominantly expressed isoform of T-channels at the soma of primary afferent fibers located in DRG, and as such is primarily responsible for subthreshold neuronal excitability (16,17,39). It has been demonstrated that increased channel activity with reducing agents or glycosylation, independent of changes in Cav3.2 mRNA and protein expression, may induce potent sensitization of peripheral nociceptors (16,17,24,25). In addition, deubiquitination of Cav3.2 channels has been introduced recently as an important mechanism of hyperalgesia in neuropathic and inflammatory pain (22). This study used immunohistochemistry to reveal that USP5, a ubiquitin protease, is co-expressed in the same classes of sensory neurons known to express Cav3.2 channels such as myelinated (NF200 positive), unmyelinated (IB4 positive) and peptidergic DRG neurons (22). This corresponds well with our previous study that these three groups of sensory neurons from DRG express abundant Cav3.2 channels as well (40). Furthermore, USP5 and Cav3.2 could be co-immunoprecipitated from DRG and spinal cord tissue (22). Our findings presented herein reveal that the increased levels of USP5 after plantar skin incision could promote deubiquitination of the Cav3.2 channel after surgery. Our data are consistent with a mechanism in which post-surgical modulation of Cav3.2 channels significantly contribute to the development of acute post-operative pain. This has been confirmed in our behavioral experiments where Cav3.2 KO mice exhibited reduced mechanical hypersensitivity after incision, as compared to WT mice. Furthermore, the process of deubiquitination supports membrane stability of the channel, which in turn could also increase current density and cause ensuing hyperexcitability of nociceptors. This suggests that silencing of USP5 could be a promising approach to reducing hyperalgesia observed post-incision. The specificity of interaction between USP5 and Cav3.2 channel was confirmed with our experiments with the Cav3.2 KO mice. However, it is well known that a global gene knockout approach is often limited by compensatory mechanisms, as was shown for the nociceptor-specific TTX-resistant sodium channel Nav1.8 KO mice (41). Hence, we confirmed the selectivity and specificity of deubiquitination by blocking the binding of USP5 to the Cav3.2 channel with the tat III-IV peptide, which ameliorated hyperalgesia in WT mice after plantar skin incision similar to the one that we observed after USP5 knockdown.

In conclusion, our study implicates T-channels in the development of post-surgical hyperalgesia following skin incision. We demonstrated that after plantar skin incision, increased current density and slower inactivation of these channels contribute to increased excitability of nociceptive sensory neurons of DRG in vitro. We confirmed this in our in vivo studies, where a selective T-channel blocker effectively alleviated both heat and mechanical hyperalgesia in rats after plantar incision. Furthermore, we showed that the Cav3.2 channel isoform is of particular importance in post-surgical acute pain, since our data reveal a significant reduction in mechanical hyperalgesia responses in both mice lacking this channel, as well as mice and rats with lower expression of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP5, which stabilizes the Cav3.2 channel in the membrane. Therefore, our data strongly suggest that the Cav3.2 isoform of T-channels could be considered a potential drug target for novel therapies for treating post-surgical pain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study objective was to investigate if T-channels are involved in mechanical and thermal nociception in vivo after plantar skin incision using adult rats and mice of both sexes (8-10 weeks of age). In addition, in vitro studies with whole DRG tissues were used for studies of mRNA and Cav3.2 protein expression. Finally, acutely dissociated DRG neurons were used for immunostaining and electrophysiology experiments for analysis of current waveforms and action potential firing properties.

All efforts were done to minimize number of animals to obtain reliable scientific data. In all our experiments sample size was chosen using standard algorithms (42) with reference to our previously published data. For each experiment, animals were randomized in experimental groups in order to generate biological replicates. For all studies rats and mice were litter-matched, age-matched and gender-matched to keep the treatment groups as similar as possible. Except for the duration of in vitro studies where animals were euthanized at different time points, all studies were predetermined to last 7 days from the incision. In order to assure stable recording conditions for the measurements of mechanical and thermal sensitivities, we determined baseline values on both paws two days prior to surgery and prior to drug application. If two baseline values obtained before surgery differed more than 20%, animals were not used for further experiments.

Animals

Experimental protocols were approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and are in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, 1996). All animals were maintained on a 12 h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. All experiments involving rats used adult Sprague-Dawley (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) female rats weighing 200-240 g. We also used wild-type C57BL/6J and CACNA1H (Cav3.2) global knockout (KO) mice, both males and females (8-10 weeks of age).

Incisional pain model

For the purposes of studying involvement of T-type calcium channels in acute post-surgical pain, we used the procedure described previously (11,23). In brief, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (2-3%) and the plantar surface of the right paw was incised longitudinally. The underlying plantaris muscle was elevated and incised, after which the skin was closed with two sutures. Each animal allowed to recover individually in a cage, and all experiments were initiated as early as 2 h post-incision.

Intrathecal injections

In order to study antinociceptive effects of spinally applied drugs, intrathecal (i.t.) injections of the study compound were performed. After anesthetizing animals with isoflurane (2-3%), the back of each animal was shaved to expose the injection site in the region of L4-L6 of the spinal column. A 28-30 G needle was used for the acute i.t. injection. After inserting the needle into the L4-L6 lumbar region, the experimental compound or vehicle was delivered i.t. (50 μl in rats and 10 μl in mice), and the animal was left to recover before initiating experiments.

Drugs

A racemic mixture of the pan-selective T-type calcium channel blocker, TTA-P2 (3,5-dichloro-N-[1-(2,2-dimethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-4-ylmethyl)-4-fluoro-piperidin-4-ylmethyl]-benzamide) was purchased from Alomone Labs (Israel) and was dissolved as suspension in 15% 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin solution in pH-balanced saline (to avoid tissue irritation) for all behavioral experiments. 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (45% solution) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and diluted to 15% using pH-balanced saline. USP5-shRNA used in experiments with mice was purchased from Thermo Scientific, Open Biosystems.

Acute dissociation of DRG neurons

DRG cells from adolescent rats were prepared as we previously described (43). In brief, animals were first deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, after which decapitation was performed, and unilateral L4-L6 dorsal root ganglia were removed and immediately placed in ice-cold Tyrode’s solution, which contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazinN'-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. After harvesting, the tissue was transferred into Tyrode’s solution containing collagenase H (Sigma Aldrich) and dispase II (Roche) and incubated for 50 minutes at 35 °C. Dissociated single neuronal cell bodies were obtained by trituration in Tyrode’s solution at room temperature through fire polished pipettes of progresivelly reduced sized tips. Following trituration, cells were plated onto uncoated glass coverslips, placed in a culture dish, and perfused with external solution. All in vitro experiments were done at room temperature. Only small to medium sized cells (< 35 μm soma diameter) were used in recordings, as our previous studies have shown that T-type calcium channels are highly expressed in these cells, which are putative nociceptors (16,17,43).

Electrophysiology

The external solution for voltage-clamp experiments measuring T-currents contained (in mM) 152 tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl, 2 CaCl2, and 10 hydroxyethyl piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), with TEA-OH, which was used for adjustment of pH to 7.4. In order to study well-isolated T-currents in acutely isolated DRG neurons, we used only fluoride (F−)-based internal solution to ensure high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ current rundown (43). The internal solution contained (in mM) 135 TMA-OH, 40 HEPES, 10 ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), and 2 MgCl2, adjusted to pH 7.2 with hydrogen fluoride (HF). Internal solution for current-clamp recordings contained the following (in mM): potassium-D-gluconate 130, EGTA 5, NaCl 4, CaCl2 0.5, Hepes 10, Mg ATP 2, Tris GTP 0.5, pH 7.2. All current-clamp recordings were performed in Tyrode’s external solution. Series resistance (Rs) and membrane capacitance (Cm) were recorded directly from the amplifier after electronic subtraction of the capacitive transients. Current densities were calculated by dividing current amplitudes with cell capacitance. Spike firing properties of DRG sensory neurons were characterized by injecting a family of depolarizing current pulses of 500 ms duration in 10 pA incremental steps through the recording pipette. Resting membrane potential was measured at the beginning of each recording and was not corrected for the liquid junction potential, which was around 10 mV in our experiments. The membrane input resistance was calculated by dividing the end amplitude of steady-state hyperpolarizing voltage deflection by the injected current.

Current-voltage (I-V) curves were generated by the voltage steps from the holding potentials (Vh) of −90 mV to test potentials (Vt) from −75 mV to −30 mV in incremental steps of 5 mV. Steady-state inactivation curves were generated by the voltage steps form Vh −90 mV to conditioning pre-pulse potentials from −110 mV to −50 mV in incremental steps of 5 mV and then to Vt of −30 mV. To study the possible effects of skin incision on the voltage dependence of deactivation kinetics, tail currents were recorded over a sufficiently negative range of membrane potentials (e.g. −160 to −60 mV in 10 mV increments), following an 8 ms-long depolarizing step to −30 mV (43).

The voltage dependences of activation and steady-state inactivation were expressed with single Boltzmann distributions of the following forms:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The time courses of macroscopic current inactivation and deactivation of tail currents were fitted using a single exponential equation:

| (3) |

yielding one time constant (τ1) and its amplitude (A1)

Thermal nociception testing

For assessment of thermal (heat) nociception threshold, an apparatus based upon Hargreaves method was used (custom created at UCSD University Anesthesia Research and Development Group, La Jolla, CA). Briefly, the system consists of a radiant heat source mounted on a movable holder positioned underneath a glass surface on which animals are placed in enclosed plastic chambers. After 15 minutes of acclimation, a radiant heat source is positioned directly underneath a plantar surface of hind paws to deliver a thermal stimulus. When the animal withdraws the paw, a photocell detects interruption of a light-beam reflection, and the automatic timer shuts off measuring the animal’s paw withdrawal latency (PWL). Each paw was tested three times and the average value of PWLs was used in further analysis. To prevent thermal injury, the light beam is automatically discontinued at 20 s if the rat fails to withdraw its paw.

Mechanical sensitivity

For the purposes of testing mechanical sensitivity of animals, we used the electronic Von Frey apparatus (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy), which consists of one single rigid probe that exerts pressure in a range from 0 to 50 grams. Animals are placed in plastic enclosures on a wire mesh stand to habituate for 15 minutes. After habituation, a probe is applied to the plantar surface of the paw through the mesh floor of the stand, and constant force is applied to the mid-plantar area of the paw. As soon the immediate brisk paw withdrawal appears as a resulting response to a punctate stimulus, the apparatus displays a force in grams that represents a threshold for paw withdrawal response (PWR). Each paw was tested three times and the average value of threshold PWRs was used in further analysis. Any other voluntary movement of animal is not considered as a response.

Assessment of sensorymotor abilities

In order to eliminate the potential of the highest applied dose of the tested drug to exert motor impairment, we tested unoperated rats in a battery of the following behavior experiments (44):

-

1)

Inclined plane: a rat was placed in the middle of a wire mesh (8 squares in 10 cm) tilted at 60° angle. The animal was placed with her head down and time was measured how long it can stay without falling down. A cut-off value of 120 s was assumed as the maximum time animal can stay on the inclined mesh.

-

2)

Elevated platform: a rat was placed on a platform (7.6×15.2 cm) 61 cm above the ground and animal was timed for how long it can remain there. A mean value was calculated from two trials with a maximum of 120s (test cut-off value).

-

3)

Ledge: a rat was timed for how long it can stay on a plank 3 cm wide. Means for each animal were calculated over two trials, with a maxiumum of 60 s per trial. The highest dose of TTA-P2 that exerted analgesic effect in healthy animals was tested 30 minutes after i.t. injection.

Quantitative real-time PCR

In order to study changes in expression of T-channel isoforms, we used tissue from dissociated lumbar dorsal root ganglia (50-70 mg of tissue per sample). RNA was isolated using RNeasy Microarray Tissue Mini Kit with QiAzol (QIAGEN), and quantitative real-time (qRT) PCR was performed on a BioRad Icycler, with RT2 First Strand Kit and RT2 SYBR Green qPCR Mastermix (QIAGEN). Melt curve analysis and no template controls were included in each run. Primers for all three T-type calcium channel subtypes were purchased from QIAGEN (CACNA1G NM_031601.4; CACNA1H NM_153814.2; CACNA1I NM_020084.3). We used cyclophilin as internal standard (QIAGEN, Ppid NM_001004279.1). qRT-PCR data was analyzed as previously described (24). In brief, cycle threshold (Ct) for cyclophilin was subtracted from each corresponding channel Ct from each sample, and relative mRNA levels expressed as 2−ΔCt were compared between sham and incised groups.

Western blot

To study expression of Cav3.2 channels, we harvested L4-L6 DRGs of rats that were previously deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, and decapitated. For incised animals, ipsilateral DRGs were collected 24 and 48 hours post-incision (for sham operated group, both ipsilateral and contralateral DRGs were collected). The DRGs of two animals were pooled into one sample for the sham-operated group, while DRGs of three incised animals were pooled into one sample, giving a total of 4 samples in each group. Tissue was homogenized with a pestle in 7 w/v volumes of modified RIPA buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl, 25mM Tris, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (#8866; Thermo Scientific, USA). Samples were exposed to three freeze-thaw cycles, sonicated (Branson) and then centrifuged (30 min; 14,000 rpm). Supernatant was placed in a clean tube, assayed for total protein (BCA; Life sciences-USA), and stored at −80 °C until use. Samples (20 μl per lane) were prepared for electrophoresis by incubating with 2X sample buffer for 1 h at 24 °C with gentle shaking. Proteins were loaded on 4-20% Tris-Glycine polyacrylamide gradient gels (Bio-Rad, USA) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% nonfat milk in TBST buffer (150mM NaCl, 50mM Tris, 0.1% Tween, pH 7.5) at room temperature, and incubated overnight (4 °C) with a primary antibody (anti-Cav3.2 (1:3.000); Alomone Laboratories; GAPDH (1:15.000), Millipore), diluted in 2.5% milk in TBST. The PVDF membrane was subsequently washed and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:15.000, Santa Cruz Biotechology) diluted in TBST (1 h; room temperature). Washing was repeated and the blot developed using enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Super Signal West Femto; Thermo Scientific, USA). Emitted light was detected with a chemiluminescence image analyzer – GBOX (Chemi XR5; Syngene, USA) and analyzed densitometrically using the computerized image analysis program ImageQuant 5.0 (GE Healthcare; Life sciences, USA). Signal intensity for Cav3.2 was normalized to GAPDH, which was used as a loading control.

To study the expression level of USP5, contralaeral and ipsilateral L4-L6 DRGs were harvested from incised WT mice. For immunoprecipitation (IP) assays, incised mouse ipsilateral and contralateral L4-L6 DRGs were lysed in RIPA buffer (in mM; 50 Tris, 100 NaCl, 1 % (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 % (v/v) NP-40, 10 EDTA + protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.5). Tissue lysates were used to immunoprecipitate USP5 with a specific USP5 polyclonal antibody (ProteinTech Group, Inc.) Lysates were prepared by sonicating samples at 60% pulse for 10 seconds twice and by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Supernatants were transferred to new tubes and solubilized proteins were incubated with 50 μl of Protein G/A beads (Piercenet) and 1 μg of anti-USP5 polyclonal antibody overnight while tumbling at 4 °C. Inputs, representing 7% of total lysate, were probed for α-tubulin with a specific mouse antibody, as loading controls. USP5 immunoprecipitates were washed twice with (mM) 500 NaCl 50 Tris pH 7.5 buffer and beads were aspirated to dryness. Laemmli buffer was added and samples were incubated at 96 °C for 10 min. Eluted samples and inputs were loaded on 10% Tris-glycine gels resolved using SDS-PAGE. Samples were transferred to 0.45 mm polyvinylidenedifluoride (PDVF) membranes (Millipore) by dry-transfer with i-blot apparatus (Invitrogen).

Western blot assays were performed using mouse anti-alpha tubulin (1:2000; Abcam) and rabbit anti-USP5 (1:500; ProteinTech Group, Inc.) antibodies. Quantification was performed using densitometry analysis (Quantity OneBioRad software).

Immunohistochemistry

The experiments were performed in a blinded manner as previously described (40,45). L4-L6 of rats DRG ganglia were harvested, and the cells were dissociated as described for electrophysiology experiments. Cells were plated onto glass cover slips and left in an cell oven for 1-3 h at 37 °C, and the wells were then flooded with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) for 10 min at 4 °C. Cells were then rinsed with 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 3 × 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then simultaneously permeabilized and non-specific binding was blocked using 0.1% Triton-X, 0.01 M PBS supplemented with 5% donkey serum for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were rinsed with 0.01 M PBS for 3 × 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then incubated in primary antibody (1:500, anti-Cav3.2 ACC-025, Alomone Labs) in 0.01 M PBS overnight at 2-8 °C. Specificity of this antibody was validated in a recently published article (46). After rinsing with 0.01 M PBS for 3 × 5 min at room temperature, cells were then left overnight to incubate with the second primary antibody (anti-pan-cadherin, 1:200 ab22744, Abcam). After rinsing with 0.01MPBS for 3 × 5 min at room temperature, cells were then incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (1:2000, Alexa Fluor 488 A27034, Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature, then rinsed again with 0.01 M PBS for 3×5 min at room temperature, and then subsequently incubated with (1:2000, Alexa Fluor 568 A11004, Invitrogen) at room temperature for 2 h. Cell plates were mounted using fluorescent medium with DAPI (Vectashield). All pictures were taken by using Olympus FV1000 FCS/RCIS confocal microscope.

Image analysis was performed in ImageJ program. Fluorescence intensities, as a measurement of cell surface expression for both Cav3.2 and pan-cadherin, were obtained by subtracting the intracellular fraction from the total cell fluorescence, for each channel. For each individual cell, the relative level of expression of Cav3.2 was obtained by normalizing the raw fluorescence intensity to the intensity of pan-cadherin. Specificity of used antibodies was confirmed in control experiments, by omitting the primary antibodies.

Data analysis and Statistics

All data from electrophysiological experiments are presented as mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism and SigmaPlot were used to analyze the data. Statistical significance was determined using either two-way repeated measures-analysis of variance (RM- ANOVA) followed by Sidak’s post-hoc test, Fisher’s exact test or Unpaired t-test as appropriate. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Data from biochemical experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM, and analyzed with either Ordinary One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test, Mann Whitney or Unpaired t-test. Behavioral data was expressed as mean ± SEM and evaluated by two-way RM-ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s or Sidak’s post-hoc test and by One-way RM ANOVA followed by Dunett’s post-hoc test, and also by Mann-Whitney test: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005).

Data sets were tested for sphericity in SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), and normality and equal variance tests were performed in SigmaPlot. If the data sets violated the sphericity or equal variance, appropriate modifications to the degreees of freedom were made so that the valid F ratio could be obtained.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Development of post-surgical thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity in rats.

Fig. S2. The lack of effect of plantar skin incision on voltage-dependent activation, voltage-dependent inactivation and deactivation kinetics of T-current in rat DRG cells.

Fig. S3. Effects of intrathecally applied TTA-P2 in unoperated rats using nociceptive testing and a battery of sensorimotor tests.

Fig. S4. Preemptive intrathecal (i.t.) application of USP5-shRNA reduces mechanical hypersensitivity post-incision in WT mice and has no effect in Cav3.2 KO mice.

Acknowledgments:

Supported by NIH grant 1 R01 GM123746-01 to SMT and VJT, the funds from the Department of Anesthesiology at UC Denver, and by a CIHR Foundation Grant to GWZ. Imaging experiments were performed in the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Advance Light Microscopy Core supported in part by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR001082. Contents are the authors' sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. We thank Dr. Alex Keizer for help with statistical analysis of the data.

Footnotes

Competing interests: authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Denson D, Katz J, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, In: Sinatra RS, Hord AH, Ginsberg B, Preble L, editors. Acute Pain: Mechanisms and Management. St. Louis, Mo, USA: Mosby; pp 112–123 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ, Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth. Analg. 97, 534–540 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer R, Patel AM, Rattana SK, Quock TP, Mody SH, Prescription opioid abuse: a literature review of the clinical and economic burden in the United States. Popul. Health Manag. 17(6), 372–387 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug poisoning deaths. December 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheetdrugpoisoning.pdf

- 5.Perkins FM, Kehlet H, Chronic pain as an outcome of surgery. A review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology 93,1123–1133 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacus MO, Uebele VN, Renger JJ, Todorovic SM, Presynaptic Cav3.2 channels regulate excitatory neurotransmission in nociceptive dorsal horn neurons. J. Neurosci. 32(27), 9374–9382 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, T-type voltage-gated calcium channels as targets for the development of novel pain therapies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 484–495 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourinet E, Alloui A, Monteil A, Barrere C, Couette B, Poirot O O, et al. , Silencing of the Cav3.2 T-type calcium channel gene in sensory neurons demonstrates its major role in nociception. EMBO J. 24, 315–324 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Joksovic PM, Lee W, Nelson MT, Naik AK, Su P, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Up-regulation of the T-type calcium current in small rat sensory neurons after chronic constrictive injury of the sciatic nerve. J Neurophysiol 99:3151–3156 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latham JR, Pathirathna S, Jagodic MM, Choe WJ, Levin ME, Nelson MT, Lee WY, Krishnan K, Covey DF, Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Selective T-type calcium channel blockade alleviates hyperalgesia in ob/ob mice. Diabetes 58(11), 2656–2665 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF, Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain 64, 493–501 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan TJ, Pathophysiology of postoperative pain. Pain 152, S33–S40 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zahn PK, Brennan TJ, Primary and secondary hyperalgesia in a rat model for human postoperative pain. Anesthesiology 90, 863–872 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteside GT, Harrison J, Bouet J et al. , Pharmacological characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 141, 85–91 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Shimizu I, Caterina M, Raja SN, Heat hyperalgesia after incision requires TRPV1 and is distinct from pure inflammatory pain. Pain 115, 296–307 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson MT, Joksovic PM, Perez-Reyes E, Todorovic SM, The endogenous redox agent L-cysteine induces T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent sensitization of a novel subpopulation of rat peripheral nociceptors. J. Neurosci. 25(38), 8766–8775 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson MT, Woo J, Kang HW, Vitko I, Barrett PQ, Perez-Reyes E, Lee JH, Shin H-S, Todorovic SM, Reducing agents sensitize C-type nociceptors by relieving high-affinity zinc inhibition of T type calcium channels. J. Neurosci. 27(31), 8250–8260 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choe W, Messinger RB, Leach E, Eckle V-S, et al. , TTA-P2 is a potent and selective blocker of T-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons and a novel antinociceptive agent. Mol. Pharmacol. 80, 900–910 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker SM, Yaksh TL, Neuraxial analgesia in neonates and infants: a review of clinical and preclinical strategies for the development of safety and efficacy data. Anesth. Analg. 115(3), 638–62 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenach JC, Curry R, Rauck R, Pan P, Yaksh TL, Role of cyclooxygenase in human postoperative and chronic pain. Anesthesiology 112(5), 1225–1233 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talley EM, Cribbs LL, Lee JH, Daud A, Perez-Reyes E, Bayliss DA, Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels. J. Neurosci. 19(6), 1895–1911 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Caballero A, Gadotti VM, Stemkowski P, Weiss N, Souza IA, Hodgkinson V, Bladen C, Chen L, Hamid J, Pizzoccaro A, Deage M, François A, Bourinet E, Zamponi GW, The deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 modulates neuropathic and inflammatory pain by enhancing Cav3.2 channel activity. Neuron 83(5), 1144–1158 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogatzki EM, Raja SN, A mouse model of incisional pain. Anesthesiology 99, 1023–1027 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Nelson MT, Mancuso S, Joksovic PM, Rosenberg ER, Bayliss DA, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Cell-specific alerations of T-type calcium current in painful diabetic neuropathy enhance excitability of sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 27(12), 3305–3316 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orestes P, Osuru HP, McIntire WE, Jacus MO, Salajegheh R, Jagodic MM, Choe W, Lee L, Lee SS, Rose KE, Poiro N, DiGruccio MR, Krishnan K, Covey DF, Lee JH, Barrett PQ, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, , Reversal of neuropathic pain in diabetes by targeting glycosylation of Cav3.2 T-type calcium channels. Diabetes 62(11), 3828–3838 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zamponi GW, Striessnig J, Koschak A, Dolphin AC AC, The physiology, pathology, and pharmacology of voltage-gated calcium channels and their future therapeutic potentials. Pharmacol. Rev. 67(4), 821–870 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francois A, Laffray S, Pizzoccaro A, Eshalier A, Bourinet E, T-type calcium channels in chronic pain: mouse models and specific blockers. Pflugers. Arch. 466(4), 707–717 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekiguchi F, Kawara Y, Tsubota M, Kawakami E, Ozaki T, Kawaishi Y, Tomita S, Kanaoka D, Yoshida S, Ohkubo T, Kawabata A, Therapeutic potential of RQ-00311651, a novel T-type Ca2+ channel blocker, in distinct rodent models for neuropathic and visceral pain. Pain 157(8), 1655–1665 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakashima YM, Todorovic SM, Pereverzev A, Hescheler J, Schneider T, Lingle CJ, Properties of Ba2+ currents arising from human alpha1E and alpha1Ebeta3 constructs expressed in HEK293 cells: physiology, pharmacology, and comparison to native T-type Ba2+ currents. Neuropharmacology 37(8), 957–972 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma K, Zhou QH, Chen J, Du DP, Ji Y, Jiang W, TTX-R Na+ current-reduction by celecoxib correlates with changes in PGE(2) and CGRP within rat DRG neurons during acute incisional pain. Brain. Res. 1209, 57–64 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim D, Park D, Choi S, Lee S, Sun M, Kim C, Shin H-S , Thalamic control of visceral nociception mediated by T-type Ca2+ channels. Science 302(5642), 117–119 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dogrul A, Gardell LR, Ossipov MH, Tulunay FC, Lai J, Porreca F, Reversal of experimental neuropathic pain by T-type calcium channel blockers. Pain 105(1–2), 159–168 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Todorovic SM, Rastogi AJ, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Potent analgesic effects of anticonvulsants on peripheral thermal nociception in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 140(2), 255–260 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shipe WD, Barrow JC, Yang ZQ, Lindsley CW, Yang FV, Schlegel KA., Shu Y, Rittle KE, Bock MG, Hartman GD, Tang C, Ballard JE, Kuo Y, Adarayan ED, Prueksaritanont T, Zrada MM, Uebele VN, Nuss CE, Connolly TM, Doran SM, Fox SV, Kraus RL, Marino MJ, Graufelds VK, Vargas HM, Bunting PB, Manning Hasbun-M, Evans RM, Koblan KS, Renger JJ, Design, synthesis, and evaluation of a novel 4-aminomethyl-4-fluoropiperidine as a T-type Ca2+ channel antagonist. J Med Chem. 10;51(13), 3692–3695 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichl S, Augustin M, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Peripheral and spinal GABAergic regulation of incisional pain in rats. Pain, 153(1), 129–141 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang C, Hu Z-P, Long H, Shi Y-S, Han J-S, Wan Y, Attenuation of mechanical but not thermal hyperalgesia by electroacupuncture with the involvement of opioids in rat model of chronic inflammatory pain. Brain Research Bulletin, 63(2), 99–103 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang ZB, Gan Q, Rupert RL, Zeng YM, Song XJ, Thiamine, pyridoxine, cyanocobalamin and their combination inhibit thermal, but not mechanical hyperalgesia in rats with primary sensory neuron injury. Pain, 114(1–2), 266–277 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Tatsui CE, Rhines LD, North RY, Harrison DS, Cassidy RM,.,.. P.M. Dougherty, Dorsal root ganglion neurons become hyperexcitable and increase expression of voltage-gated T-type calcium channels (Cav3.2) in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain, 158(3), 417–429 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayoola C, Hwang SM, Hong SJ, Rose KE, Boyd C, Bozic N, Park JY, Osuru HP, DiGruccio MR, Covey DF, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Inhibition of Cav3.2 T-type calcium channels in peripheral sensory neurons contributes to analgesic properties of epipregnanolone. Psychopharmacol. (Berl). 231(17), 3503–3515 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rose KE, Lunardi N, Boscolo A, Dong X, Erisir A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Immunohistological demonstration of Cav3.2 T-type voltage-gated calcium channel expression in soma of dorsal root ganglion neurons and peripheral axons of rat and mouse. Neuroscience, 250, 263–274 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akopian AN, Souslova V, England S, Okuse K, Ogata N, Ure J … J.N . Wood, The tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel SNS has a specialized function in pain pathways. Nat. Neuroscience, 2(6), 541–548 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kraemer HC, Theimann S, How many subjects? Statistical power analysis in research. Sage, Newbury Park (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Todorovic SM, Lingle CJ CJ, Pharmacological properties of T-type Ca2+ current in adult rat sensory neurons: Effects of anticonvulsant and anesthetic agents. J. Neurophysiol. 79, 240–252 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wozniak DF, Olney JW, Kettinger III L, Price M, and Miller JP, Behavioral effects of MK-801 in the rat. Psychopharmacology, 101,47–56 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ritter DM, Zemel BM, Hala TJ, O’Leary ME, Lepore AC, Covarrubias M, Dysregulation of Kv3.4 Channels in Dorsal Root Ganglia Following Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurosci. 35(3), 1260–1273 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Proft J, Rzhepetskyy Y, Lazniewska J, Zhang FX, Cain SM, Snutch TP, Zamponi G, Weiss N, The Cacna1h mutation in the GAERS model of absence epilepsy enhances T-type Ca2+ currents by altering calnexin-dependent trafficking of Cav3.2 channels. Scientific Reports., 7(1), 1–13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Development of post-surgical thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity in rats.

Fig. S2. The lack of effect of plantar skin incision on voltage-dependent activation, voltage-dependent inactivation and deactivation kinetics of T-current in rat DRG cells.

Fig. S3. Effects of intrathecally applied TTA-P2 in unoperated rats using nociceptive testing and a battery of sensorimotor tests.

Fig. S4. Preemptive intrathecal (i.t.) application of USP5-shRNA reduces mechanical hypersensitivity post-incision in WT mice and has no effect in Cav3.2 KO mice.