Abstract

Primary objective:

Preliminarily explore parents’ health literacy and knowledge of youth sport league rules involving concussion education and training, and return-to-play protocols.

Research design and methods:

This study was guided by the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) model of health knowledge to examine parents’ concussion literacy, and understanding of concussion education and training, and return-to-play protocols in youth sports. The mixed-method design involved 119 participants; that included in-person (n=8) and telephone (n=4) interviews, and web-based surveys administered through Mechanical-Turk via Qualtrics (n=98).

Main outcomes and results:

Most respondents were not familiar with concussion protocols, but trust coaches’ knowledge in return-to-play rules. More than half of the respondents report that the return-to-play concussion criteria have not been clearly explained to them. The majority of respondents were not familiar with the CDC’s “Heads Up” online concussion training program, nor were they familiar with any other educational/training tool. About one fifth of the parents had conversations with a coach or medical staff about youth-sport concussions.

Conclusion:

Parents have a general understanding of how to identify concussion symptoms, but lack knowledge of immediate steps to take following an incident other than seeking medical help.

Keywords: Youth Sports, Parents, Education, Concussion literacy, Return-to-play, Health-Literacy, Concussion Education

1. Introduction

In recent years the topic of sport concussion among children and young adolescent athletes has increasingly captured the interest of the public and researchers. Despite an upswing in the number of reported concussions over the past decade, a lack of data exists concerning the overall incidence of sports-related concussions among youth [1]. Beyond the concerns for health consequences, understandings of social behavior around youth concussions are lagging. We know little about the social determinants of concussions and surrounding behaviors, including the effects of increasing parental literacy and adherence to return-to-play guidelines [1–3]. Upon convening an expert committee to review the science of sports-related concussions in youth, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the National Research Council recommends efforts to increase knowledge about the culture (e.g. social norms, attitudes, and behavior) surrounding youth sport concussions [1]. A sociological and behavioral investigation will be particularly useful for identifying practical applications and policy relevant solutions that enhance the health and well-being of youth with concussion.

Between 2009 and 2015, fifty states and the District of Columbia enacted legislation to address youth sports-related concussions. The vast majority of these laws contained a provision for concussion education or training, removing youth a youth athlete from play or practice in an even of a suspected concussion, require clearance by a designated health care provider prior to return-to-play [4]. Because it is difficult to determine the impact of this legislation without adequate measures of parental concussion knowledge and return-to-play protocols, policy makers and various youth sport stakeholders will benefit from an examination of parental concussion health literacy and knowledge of youth sport return-to-play criteria [1,5].

Collecting accurate data on mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) – often referred to as a sport concussion – is hampered by the culture of sports, which may negatively influence athletes from self-reporting concussions and the adherence to return-to-play guidelines. Although research is providing medical professionals with a better understanding of concussions, young athletes are often guided by the notion of toughness as a key attribute of sports participation, so physicians are frequently not consulted after such injuries [6]. Young athletes, and in some cases parents and coaches, may not fully appreciate the short and long-term sequelae of concussions [7]. Previous research found 91% of students understood that they would be at risk of serious injury if they returned to play too soon, but only 50% of high school football players would “always” or “occasionally” tell their coaches about their concussion symptoms [8–10]. Because of their status as young athletes, sport participation may have important health and behavioral implications, particularly with regard to concussions [6].

Although research on the etiology of concussions is advancing rapidly, work on the social determinants and consequences of concussions have moved more slowly. Despite public health concerns associated with youth sport concussion, it remains difficult to draw strong conclusions about best practices. This challenge suggests the need for field research that examines issues around literacy, culture, attitudes, and behavior involving concussions in youth sports. Such research with parents, coaches, team administrators, and other stakeholders charged with making youth sport return-to-play concussion decisions would be particularly valuable [11–13].

Limited studies exist that evaluate parental knowledge of youth sport concussions [1–3,14–16]. Yet, research focused on this topic points to differences in concussion literacy among parents of youth athletes. For example, 83% of parents of young rugby athletes in New Zealand were able to provide a list of well-accepted concussion signs and symptoms. In contrast, U.S. data suggests that important misconceptions surrounding concussions continue to persist among parents of youth athletes. Building on the work of Mannings et al., [2014][2] the present study was designed to collect preliminary data on parent’s awareness of concussion education websites (e.g. CDC “Heads Up”), knowledge of youth sport league rules involving concussion education and training, and return-to-play protocols.

2. Methods

This study was conducted using a triangulation mixed methods design based on Creswell’s typology (chap 17) to test the Knowledge, Attitude, Practice model (KAP) of health knowledge, which suggests that increasing a person’s health literacy will prompt a behavior change [17,18]. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected in parallel, analyzed separately then merged. The development and validation (e.g. face, validity, content, criterion) of our data collection instruments were guided by scientific methods used in athletic training survey research [19]. Our domain was identified by conducting a search of Google Scholar, PubMed, Medline, and Web of Science databases for relevant publications on concussion health education and literacy between 2013–2014. Previous concussion and sports injury-related questionnaires were collected and included as items in our data collection efforts to assess participants’ concussion literacy, knowledge of league rules involving concussion education, training, and return-to-play procedures for youth sports. Our “proof of concept” study was conducted using multiple sources of data including: 1) in-person (n=8) and telephone (n=4) interviews, and 2) online surveys (n=98). For the purposes of this study youth athletes were defined as children from the age of 5–14 years. Informed verbal or written consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for all participants included: parents and guardians with at least one child between the age 5–14 playing youth tackle football or participating in other organized youth sports (e.g. recreational, in-school, intramural, club, team, and individual), and living in the United States. Each interview lasted approximately 20 minutes. Data from the in-person interviews were collected from 6 parents and 2 parent-volunteer coaches during a youth football game in Washington D.C in fall 2014. An additional cohort of 4 parents living in Anne Arundel County, Maryland (three of whom also served as volunteer youth coaches) completed the survey interview by phone, for a total of 12 in-person and phone survey participants.

Additionally, we created and administered a 20-minute anonymous survey instrument through Mechanical Turk – a marketplace for work that requires human intelligence – via Qualtrics. Survey and interview instruments contained questions about participants’ concussion literacy and knowledge of league rules involving concussion education, training, and return-to-play procedures. A recruitment letter was placed in the MTurk online marketplace to solicit and prescreen adult participants. At the completion of each questionnaire a unique confirmation number was assigned and data was stored securely on a password-protected server.

Data Collection

All participants were asked questions that fell into three categories: demographic (age, gender, race, education, marital status, household composition, income), child-specific, and injury-specific. Child-specific questions included type of sport their child participates in, team vs. individual, child’s age, school or league sport, pay for play status, volunteer coach participation, duration of participation, and frequency of practices. Under this category, we asked about sport-related injuries and frequency. We also asked about parents’ knowledge of concussion symptoms, sport-league rules, and return-to-play protocols. A snowball sampling technique was used to recruit face-to-face and telephone participants, and a non-probability sampling method was employed to collect data for the web-based survey [20,21].

In the tradition of Gorden [1992][22], the data collected from interviews and web-based surveys were coded and placed into related groupings. We assigned category symbols then classified relevant information, which consisted of underlying pertinent words and phrases to indicate perceptual similarities and differences in concussion literacy and return-to-play guidelines. The coding interview response process permitted for analysis of data that identified patterns and ideas that helped explain those patterns [23].

Statistical analysis

Data were presented using descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, medians, ranges, and proportions. Dependent variables were captured through a series of health literacy, concussion, and return-to-play protocol related questions (e.g., how familiar do you feel you are with the rules/procedures that determine when a child can return-to-play following an injury, how well do you think coaches know the rules/procedures that determine when a child can return-to-play following an injury, do you know what concussions signs and symptoms to look for). We determined the mean value for questions that used Likert scales; and nominal level data were coded 1=yes, 2=no, 3=not sure. Multi-variable regression analysis was performed to assess significant predictors associated with participant familiarity with the CDC “Heads Up” website [24]. Data was analyzed using STATA, version 12.1.

3. Results

Survey demographic data

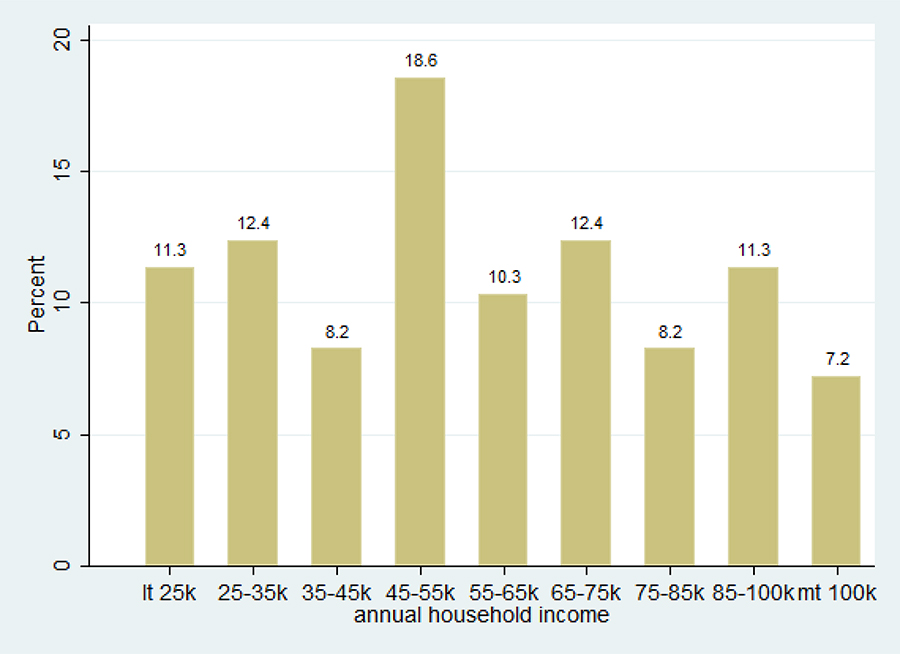

Data were collected from a total of 110 adults. The average age of the participants is 34 (19–59), with women accounting for 53% of the respondents. The racial distribution of the group is 82% Non-Hispanic White, 4% Non-Hispanic Black, 2% Hispanic, and 5% Asian. All respondents reported graduating from high school with 40% attaining a bachelor’s degree. Sixty-four percent of the participants report being married, 10% indicated being single, 13% currently live with partners, and 12% (n= 13) reside in a single-parent household. Household income distribution ranged from 11.3% with ≤$25K to 7.2% with ≥$100K (Table 1.). According to the Current Population Survey, the median household income in 2014 was $53,657[25]. The 50th percentile in our study falls in the category of $45-$55k. Therefore, the median household income in our study is comparable to the general population, with a slightly higher representation in lower and middle class households.

Table 1.

Distribution of household income

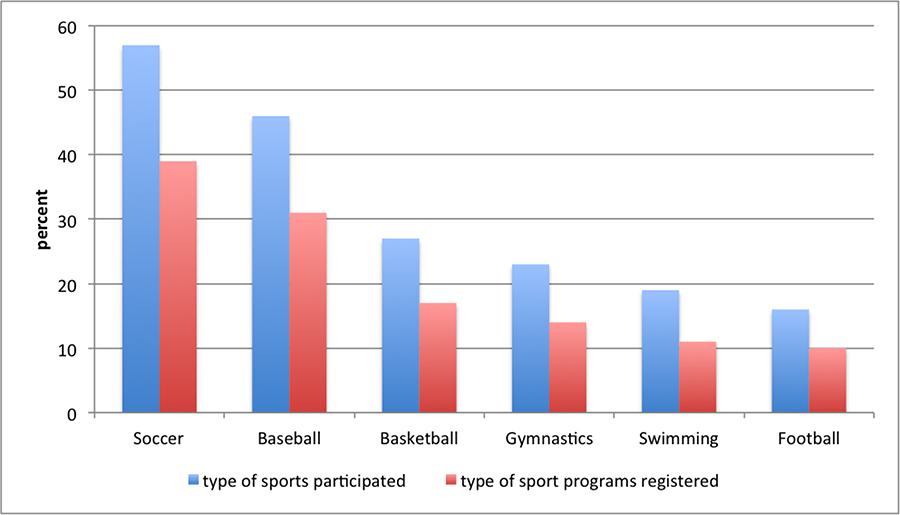

Youth sport involvement

More than 90% of respondents’ reported that their children are engaged in team sports. Parents indicated the top six organized or pick-up sports that their children participate in included soccer (57%), baseball (46%), basketball (27%), gymnastics (23%), swimming (19%), and football (16%). Among children registered for organized youth programs at present, 39% play soccer, 31% play baseball, 17% play basketball, 14% participate in gymnastics, 11% swim, and 10% play football (Table 2.). The mean age of children – represented in our study – that participated in organized youth programs was 8.6 (ages 5–14), and 53% were males. The average duration of participation was two and a half years (1–8 years, sd: 1.56). On average, youth had 2.8 practices (0–8 practices, sd: 1.45) and played 1.5 games (0–10 games, sd: 1.39) per week. These data show that majority of youth athletes played school-based (60%) and/or recreational league sports (67%). About 90% of the respondents reported paying fees for their child’s participation in sports.

Table 2.

Type of sports participated & registered

Coaching experience

A total of 16 (14.5%) respondents reported serving as a volunteer coach for at least one season of organized youth sports (8 in soccer, 7 in baseball, and 3 in basketball, hockey, and cheerleading). The majority of volunteer parent coaches worked with athletes between the ages of 5 and 10 years old.

Youth sport injury

Overall, 21% (n=23) of the respondents reported children being injured while playing organized sports. Concussions (n=2), bruises and scratches (n=4), fractures (n=6), and joint injuries (n=12), were among the most common injuries sustained by children playing organized youth sports. The most common youth sports in which injuries occur included soccer (n=15), baseball (n=5), football (n=4), and basketball (n=2). Most parents were present when injuries occurred (45%) and went to the school’s medical staff, personal doctors, or hospital with their children.

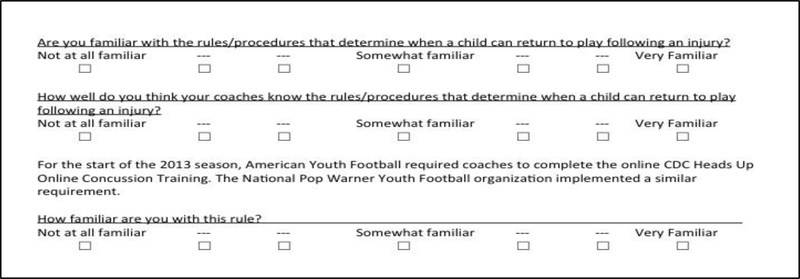

Most respondents were not familiar with concussion protocols (3.09 on a 7-point Likert scale), but trusted coaches’ knowledge of return-to-play rules (5.28). (Figure 1.) More than half of the respondents (55%) reported that the return-to-play rules and procedures involving concussions had not been clearly explained to them.

Figure 1.

Example of Likert Scale Concussion Survey

The majority of respondents (73%) have never heard of CDC’s website Heads Up to Youth Sports: Online Training for parents [24]. Parents knew little about the Heads Up Football Coaches Training Program (2.48 on a 7-point Likert scale), and only 6% were aware of the American Youth Football & Cheerleading Association rule that required coaches to successfully complete the CDC Heads Up online concussion training program annually. In the multi-variable regression analysis, only respondents’ level of education is positively associated with familiarity with the CDC “Heads Up” website (Table 3.). When probed to offer specific details about their knowledge of concussions, 13 respondents (14%) reported they knew nothing about head concussions. Of the remaining 84 participants that answered this question, 51% were aware of life-threatening or life-long effects; 38% specified concussions are diagnosable; 33% stated medical treatment is required; 25% discussed physical signs and symptoms; 17% indicated cognitive signs and symptoms; and 10% stated history or rising public attention on NFL and youth sports concussion rules and prevention. Nearly 1 out of 5 parents have had a conversation with a coach or medical staff about concussions. Parents report they have knowledge of concussion symptoms (4.45 on a 7-point scale). In the response to the open-ended question, “Can you name some of the concussion signs and symptoms to look for?” the top six answers were as follows: dizziness (60%); headache (47%); confusion (43%); nausea (22%); blurred vision (21%), and vomiting (20%). When asked, “Can you describe what steps should be followed upon learning that a child has experienced a sports concussion?,” the top responses included: go to the ER/hospital right away (74%); sit them down/take rest (23%); keep them awake (16%); and, assess severity before going to hospital (12%). Women reported knowing more about concussion signs and symptoms than men (Table 4.). Respondents were generally concerned with youth sport concussions (4.66 on a 7-point scale). Controlling for gender, age, race, education, and marital status, participants who reported with higher household income intervals showed greater concerns for youth sport concussions than those with lower income levels.

Table 3.

Familiarity with CDC “Heads Up” website.

| Familiar with CDC “Heads Up” | Coef. | T-score | P>| t| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .4319403 | 1.52 | 0.132 |

| Age | -.0106321 | -0.50 | 0.621 |

| Education | .2591754 | 2.39 | 0.019 |

| Marital Status | -.1402572 | -.0.66 | 0.513 |

| Race | .015626 | 0.10 | 0.922 |

| Household Income | -.036614 | -0.60 | 0.301 |

Table 4.

Concussion signs and symptoms*

| Knowledge of concussion signs | Coef. | T-score | P>| t| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .7538341 | 2.27 | 0.025 |

| Age | .0068848 | 0.28 | 0.784 |

| Education | -.1364397 | -1.08 | 0.283 |

| Marital Status | -.1542426 | -.0.62 | 0.537 |

| Race | -.1649793 | -0.89 | 0.377 |

| Household Income | .1007088 | 1.40 | 0.164 |

Measured on a 7point Likert scale (continuous dependent variable analyzed in linear regression model)

Qualitative data

Three overall themes emerged from the qualitative data: (a) parents had limited specific knowledge about head concussions, (b) parents primarily rely on coaches to identify concussion symptoms and to communicate this information to them, (c) parents that serve as volunteer coaches report receiving concussion education and are knowledgeable about return-to-play protocols.

Parental knowledge of sport concussions

Qualitative interviews revealed that parents have limited knowledge about head concussions in youth sports. This quote by a 35-year-old married mom of an 8-year-old male football player from Anne Arundel County Maryland is indicative of the typical response.

Well, as soon as you start asking about that, I’m like gosh, I really don’t know that much, but I know it’s a huge concern with football in particular. I’ve heard, only anecdotally, about other parents and their sons who have had concussions and what that entails, sort of having them not go to school, not watch TV, how to be aware of bright light conditions, and sustain that for a matter of days until they’re given the go-ahead to resume. But I’ve never experienced any of that first hand, it’s all been word of mouth and anecdotal, and because it hasn’t touched me yet. I haven’t really ever done much research or Googling or anything about it.

While acknowledging concerns about youth sports concussions, none of the parents in our study had consulted with medical staff or health care professionals about identifying concussion symptoms or treating an athlete with concussion. Likewise, parents disclosed that they did not consult the CDC Heads Up website, or any other webpage for youth sport concussion education materials.

Reliance on coaches to identify sports concussions

A second theme present in the qualitative data is parent’s reliance on coaches to identify concussion symptoms and their dependence on emergency room treatment. Although most parents are unaware if coaches receive formal concussion training, they are confident in their coaches’ ability to instruct them once an injury occurs. Seven of the twelve parents we interviewed said they were not aware if the coaches or athletic trainers on their child’s team received concussion training. A mother in Anne Arundel County offered the following response to a question about proof of team staff receiving youth sport concussion training. “I’m kind of embarrassed to admit it honestly, but I’ve been relying on our football coaches too much. I just figure they know about concussions.” Likewise, eight parents stated that, to their knowledge, no member of their child’s coaching or medical staff explained rules involving the return-to-play concussion protocol.

Coaches’ concussion & return-to-play education

Face-to-face interview and telephone survey data also indicates that volunteer parent coaches are knowledgeable of youth concussions and return-to-play procedures. Volunteer parent coaches in both Washington DC and Anne Arundel County confirmed that concussion education and return-to-play training are mandatory league requirements. The commissioner of the Washington DC youth football team stated that it is compulsory for coaches in their league to complete the CDC Heads Up online concussion training program. His response is consistent with the rules posted on the American Youth Football & Cheer website [26], ‘for the 2014 season, all coaches are required to complete the online CDC Heads up Online Concussion Training.’ To ensure that coaches are properly trained and educated about youth sport concussions, the DC commissioner said teams are required to retain a copy of each coaches’ certificate of competition each season.

Similarly, a father in Anne Arundel County explained that parents are required to know the return-to-play concussion protocol before they can volunteer as youth sport coaches. “In my league it’s been very clearly explained to the coaches that hey, if a kid want to come back after a head injury, they have to have a doctor’s note, or even if it’s a broken bone. I require a doctor’s note because, you know, some parents won’t actually do it.” According to this father, no such requirement exists for non-volunteer parents to know the return-to-play rules and procedures. “I would say on the teams my kids play on, no, parents aren’t required to know anything about concussions; which, is kind of interesting now that you’ve pointed it out.” This father’s comments suggest that volunteer parent coaches may have a higher level of concussion education than less-active parents of youth sport athletes. Likewise, our qualitative data suggests volunteer parent coaches have greater knowledge of return-to-play protocols and procedures than their peers.

4. Discussion

Results from our online survey and qualitative data collection methods consistently show that parents of youth athletes are not familiar with return-to-play concussion protocols. Both interview and survey data reveal the rules and procedures involving youth sport concussions have not been clearly explained to parents and guardians. Our mixed methods approach also discovered that parents indicate an overwhelming reliance on youth sport coaches to inform them of a child’s injury. The majority of youth injuries reported in this study were joint-related therefore, the opportunity to analyze parents’ behavior following a concussive event was limited.

Recent data indicate that 300,000 sport-related concussions occur annually; however, data are significantly lacking about concussions among grade school and middle school athletes [6]. Knowledge and misconceptions about mTBI have been assessed in other populations, yet concussion symptoms may be under-identified by parents and coaches of young athletes [27,28]. The misunderstandings parents and coaches often have about concussions may be improved through education [13,29], but there is a paucity of research on the effectiveness of sport concussion education [30]. Such uncertainties highlight the benefits of conducting an examination of practices and behaviors around youth sport concussions and repetitive head-impacts. It is crucial that such studies explore and identify predictors and modifiers of outcomes, including the possible influences of SES, race and ethnicity, sex, co-occurring conditions, climate (e.g. policies, practices, and procedures for the treatment of concussions), and culture (e.g. norms and values around dealing with concussions), as well as the roles of parental literacy, education, and the factors that make reporting most likely [1].

The mixed method design used for this study accomplished multiple objectives. It allowed us to gain insight on parental health literacy involving youth sport concussions, and knowledge of league rules related to education, training and return-to-play protocols for concussions. Additionally, the data provides insight into the extent that parents depend on coaches to inform them about youth sport concussion. Rather than rely on their own (perceived) ability to identify concussion symptoms, parents indicated a preference to empower youth sport coaches to inform them when or if children are injured. According to our data, emergency room staff, pediatricians, athletic trainers, and school nurses would generally be consulted only once a coach informed parents their child might have experienced a concussion. These data also suggests that parents are often unfamiliar with the CDC Heads Up website and do not typically use educational resources to learn about youth sport concussions or return-to-play rules.

Statistically significant differences emerged from the data when parents were asked if they believed they know how to identify concussion signs and symptoms. Parents who reported having college degrees were positively associated with awareness of the CDC “Heads Up” website. Parents from higher income households are more likely to show concern for youth sport concussions than those with lower income levels. Our results suggest that lower parental socio-economic-status (SES) may adversely influence the recognition of concussion symptoms, and knowledge of return-to-play rules and procedures.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size and the lack of a racially diverse population. As a result, we are unable to determine how race and SES impacts parents’ concussion literacy, knowledge of youth sport league rules involving concussions education, training, and return-to-play protocols. While participants in this study reported most athletes were engaged in youth team sports, only one-fifth of the children experienced some type of injury. Of all the reported cases of injury (20), only 2 were the result of concussion (10%). These results might not be representive of a national sample due to the low number of reported concussions and smaller presence of football participation, which nationally has the most participants in youth sports [31]. Future research that contains large-scale data collected from a nationally representative sample might impact these overall findings.

5. Conclusion

Although youth sport-concussions are a central public health priority, understandings of the etiology and epidemiology of concussions have run ahead of empirical understandings of the social influences and consequences of behaviors that surround concussions. Despite clear theoretical and clinical relevance of maintaining a healthy physically active lifestyle, the field lacks knowledge of the negative and positive reinforcement mechanisms needed to study safety, reduction and control, prevention of, and response to sports injuries. Recent advances in sports medicine discuss the need for research on real-life sport injury [32]. Such views call for a more behavioral focused approach when it comes to research and clinical practice around youth concussions and other sport injuries. Similar to findings in previous studies, the data from this study indicate a greater need for research that considers the attitudes and behavior of parents and coaches around youth concussions, while attending to the contexts in which concussion symptoms are diagnosed, and return-to-play decisions occur.

Our study represents an important next step in understanding parental health literacy involving youth sport concussions. Beyond the importance of expanding upon previous sports injury research, data in this study suggests a clear need for a more extensive study in response to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the National Research Council recommendation to increase knowledge about the culture (e.g., social norms, attitudes, and behavior) surrounding youth sport concussions [1].

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interes

References:

- [1].Graham R, Rivara FP, Ford MA, Spicer CM, others. Sports-Related Concussions in Youth: Improving the Science, Changing the Culture. National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mannings C, Kalynych C, Joseph MM, Smotherman C, Kraemer DF. Knowledge assessment of sports-related concussion among parents of children aged 5 years to 15 years enrolled in recreational tackle football. Journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2014; 77(3): S18–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lin AC, Salzman GA, Bachman SL, Burke RV, Zaslow T, Piasek CZ, Edison BR, Hamilton A, Upperman JS. Assessment of parental knowledge and attitudes toward pediatric sports-related concussions. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2015:1941738115571570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].National Conference of State Legislatures. Traumatic Brain Injuries Among Youth Athletes. Traumatic Brain Injuries Among Youth Athletes. 2016. [accessed 2016 Dec 10].

- [5].Taylor HG, Yeates KO, Wade SL, Drotar D, Stancin T, Minich N. A prospective study of short-and long-term outcomes after traumatic brain injury in children: behavior and achievement. Neuropsychology. 2002;16(1):15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Halstead ME, Walter KD, others. Sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):597–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McCrea M, Hammeke T, Olsen G, Leo P, Guskiewicz K. Unreported concussion in high school football players: implications for prevention. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2004; 14(1): 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anderson BL, Gittelman MA, Mann JK, Cyriac RL, Pomerantz WJ. High school football players’ knowledge and attitudes about concussions. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kroshus E, Garnett B, Hawrilenko M, Baugh CM, Calzo JP. Concussion under-reporting and pressure from coaches, teammates, fans, and parents. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;134:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Register-Mihalik JK, Guskiewicz KM, McLeod TCV, Linnan LA, Mueller FO, Marshall SW. Knowledge, attitude, and concussion-reporting behaviors among high school athletes: a preliminary study. Journal of athletic training. 2013;48(5):645–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Covassin T, Robert Elbin III JLS, others. Current sport-related concussion teaching and clinical practices of sports medicine professionals. Journal of athletic training. 2009;44(4):400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Covassin T, Elbin RJ, Sarmiento K. Educating coaches about concussion in sports: evaluation of the CDC’s “Heads Up: Concussion in Youth Sports” initiative. Journal of school health. 2012;82(5):233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McLeod TCV, Schwartz C, Bay RC. Sport-related concussion misunderstandings among youth coaches. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2007;17(2):140–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gourley MM, McLeod TCV, Bay RC, others. Awareness and recognition of concussion by youth athletes and their parents. Athletic Training and Sports Health Care. 2010;2(5):208–218. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sullivan SJ, Bourne L, Choie S, Eastwood B, Isbister S, McCrory P, Gray A. Understanding of sport concussion by the parents of young rugby players: a pilot study. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2009;19(3):228–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stevens PK, Penprase B, Kepros JP, Dunneback J. Parental recognition of postconcussive symptoms in children. Journal of trauma nursing. 2010;17(4):178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Organization WH, others. Health education: theoretical concepts, effective strategies and core competencies: a foundation document to guide capacity development of health educators. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Creswell JW, Maietta RC. Qualitative research. Handbook of research design and social measurement. 2002;6:143–184. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Turocy PS. Overview of athletic training education research publications. J Athl Train. 2002;37(suppl 4):S162–S167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Heckathorn DD. Comment: snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociological methodology. 2011;41(1):355–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fricker RD. Sampling methods for web and e-mail surveys. N. Fielding. 2008:195–216. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gorden R, Itasca IL, Peacock FE. Coding interview responses. 1998.

- [23].Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Rowman Altamira; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [24].CDC. HEADS UP to Youth Sports: Resources for Parents. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. December 23 Available from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/youthsports/parents.html

- [25].DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Current population reports, income and poverty in the United States: 2014. Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [26].American Youth Football & Cheer - The World’s Largest Youth Football and Cheer Organization. http://www.americanyouthfootball.com/

- [27].Hajek CA, Yeates KO, Taylor HG, Bangert B, Dietrich A, Nuss KE, Rusin J, Wright M. Agreement between parents and children on ratings of post-concussive symptoms following mild traumatic brain injury. Child Neuropsychology. 2010;17(1):17–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kutcher JS, Eckner JT. At-risk populations in sports-related concussion. Current sports medicine reports. 2010;9(1):16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mrazik M, Bawani F, Krol AL. Sport-related concussions: knowledge translation among minor hockey coaches. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2011;21(4):315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Echlin PS, Johnson AM, Holmes JD, Tichenoff A, Gray S, Gatavackas H, Walsh J, Middlebro T, Blignaut A, MacIntyre M, et al. The Sport Concussion Education Project. A brief report on an educational initiative: from concept to curriculum Special article. Journal of neurosurgery. 2014;121(6):1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zemper ED. Catastrophic injuries among young athletes. British journal of sports medicine. 2010;44(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Verhagen EA, van Stralen MM, Van Mechelen W. Behaviour, the key factor for sports injury prevention. Sports medicine. 2010;40(11):899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]