Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of homework-task difficulty and electronic-diary reminders on written homework completion during cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for addiction. Completion of homework is an important element in CBT that may affect outcome.

Design:

All participants received all combinations of our two interventions in a factorial 2×2 counterbalanced Latin-square design.

Methods:

Methadone-maintained cocaine and heroin users were given homework between each of 12 weekly CBT sessions and carried electronic diaries that collected ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data on craving and exposure to drug-use triggers in four 3-week blocks assessing two levels of homework difficulty and prompted and unprompted homework.

Results:

Neither simplified (picture-based) homework nor electronic reminders increased homework completion. In EMA reports, standard but not simplified homework seemed to buffer the craving that followed environmental exposure to drug cues. EMA recordings before and after the CBT intervention confirmed a decrease over time in craving for cocaine and heroin.

Conclusions:

These findings demonstrate the utility of EMA to assess treatment effects. However, the hypothesis that simplified homework would increase compliance was not supported.

Keywords: cognitive-behavioral therapy, homework assignments, methadone maintenance, simplification, prompting, homework compliance

1. Introduction

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is efficacious for treatment of substance-related disorders (Carroll & Onken, 2005); in fact, except for contingency management (CM, a behavioral intervention), it is the most strongly supported intervention for the treatment of cocaine-related disorders (Rawson et al., 2006). An important component of CBT is its emphasis on acquisition of new skills (Andrews, Crino, Hunt, Lampe, & Page, 1994; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Beck, Wright, Newman, & Liese, 1993). In CBT for cocaine-related disorders, the patient learns to identify thoughts, feelings, and events that precede and follow each episode of cocaine use and to develop and rehearse coping skills, both drug specific (e.g., avoiding or resisting drug-associated cues) and general (e.g., managing negative affect and finding nondrug sources of reinforcement; Beck et al., 1993). However, like any treatment for substance misuse, CBT has limitations. For example, CBT can be less effective than CM in inducing initial abstinence (Epstein, Hawkins, Covi, Umbricht, & Preston, 2003).

One impediment to good outcomes in CBT may be impairments in cognitive function, which can be associated with chronic substance misuse (Aharonovich et al., 2006; Aharonovich, Nunes, & Hasin, 2003; Bolla, Rothman, & Cadet, 1999; Di Sclafani, Tolou-Shams, Price, & Fein, 2002). In one trial of CBT for substance dependence, coping skills improved more among patients with higher baseline IQs, and these improvements predicted reductions in substance use after treatment (Kiluk, Nich, & Carroll, 2010). Beck (1995) pointed out that CBT can be intellectually demanding, as it relies on the patient’s ability to access and evaluate automatic thoughts, to distinguish among mood states, and to understand relationships among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Those who benefit most from CBT tend to be those who can best assimilate the relevant skills (Safran, Segal, Vallis, Shaw, & Samstag, 1993; Safran, Vallis, Segal, & Shaw, 1986).

Although cognitive abilities should be considered when assessing whether CBT is a good fit for a patient (Safran, et al., 1993), CBT can be effective even in patients with marked cognitive impairment (Hatton, 2002; Taylor, Lindsay, 7& Willner, 2008). The challenge is to adapt CBT materials in ways that decrease the verbal load (e.g. Willner & Tomlinson, 2007) without undermining CBT’s underlying principles (Stenfert-Kroese, Dagnan, & Loumidis, 1997; Whitehouse, Tudway, Look, & Stenfert-Kroese, 2006; Willner, 2006).

One of the distinctive features of CBT is homework, or between-session assignments intended to generalize in-session learning to everyday living and to enable rehearsal of relevant skills (Beck, et al., 1979; Blackburn & Twaddle, 1996; Detweiler & Whisman, 1999). Homework adherence predicts end-of therapy improvement, symptom reduction, and a reduction in the consequences of relapse (Dimeff & Marlatt, 1998; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2000; Kazantzis, Whittington, & Dattilio, 2010; Neimeyer, Kazantzis, Kassler, Baker, & Fletcher, 2008; Rees, McEvoy, & Nathan, 2005). For example, in cocaine-dependent individuals, Carroll, Nich, & Ball (2005) found a direct relationship between completion of CBT homework assignments and therapeutic outcome (including acquisition of coping skills and reduction in cocaine use during treatment). Adherence to homework is related to the acceptability of the homework, i.e., the patient’s beliefs about its difficulty in relation to his or her abilities (Tompkins, 2002) and about its relevance to his or her problems (Conoley, Conoley, Ivey, & Scheel, 1991; Conoley, Padula, Payton, & Daniels, 1994). Adherence to homework may also be improved by regular reminders (Kimhy & Corcoran, 2008; Mohlman et al., 2003).

Given the importance of homework in CBT for addictions, as well as relationships between cognitive function and outcome in CBT (Aharonovich, et al., 2006; Aharonovich, et al., 2003), we investigated two interventions that we hypothesized would increase homework completion: the use of electronic devices to remind participants to complete their homework, and the use of simplified homework. We also hypothesized that simplification would improve engagement with homework, in terms of quality, enthusiasm, and understanding. We tested our interventions in a within-subjects design among heroin/cocaine users enrolled in methadone maintenance and receiving CBT to reduce their drug use.

For more complete assessment of the interventions, we collected ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data on handheld electronic diaries. EMA data collected through randomly timed prompts enable assessment of the base rates of exposure to putative craving/lapse triggers in a prospective manner. Using EMA data, we have previously shown that exposure to triggers increases in the hours before cocaine use [citation removed for masked review]. In the present study, we used EMA to assess whether, following daily-life experience of triggers such as drug-cue exposure and negative affect, there was an association between a given week’s exposure to CBT homework (standard, simplified, or incomplete) and craving for cocaine. We also used EMA to assess whether drug craving generally decreased during the study in the sample as a whole.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and setting

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of [removed for masked review] approved this study. Each participant gave written informed consent before enrollment. Participants were physically dependent on opioids (by self-report, urine screen, and physical examination), were aged 18–65 years, and reported recent use of cocaine and heroin use (verified by urine screen). We excluded individuals with current psychotic or untreated major depressive disorder, current dependence on alcohol or any sedative hypnotic (all by DSM-IV criteria), a history of bipolar disorder, a medical illness that would compromise study participation, or cognitive impairment severe enough to preclude informed consent or valid self-report. General intellectual function was estimated using the Shipley Institute of Living Scale (Shipley, 1940), and the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - 3rd Edition (PPVT-III; (Dunn & Dunn, 1997). The study was conducted in [removed for masked review].

2.2. Standard treatment

At enrollment, participants began methadone maintenance. Doses were individualized based on opioid use, suppression of withdrawal discomfort and craving, and avoidance of intoxication and side effects. Participants attended clinic 7 days a week for up to 28 weeks, had weekly case-management meetings with a master’s-level counselor (except as described below), and provided urine specimens thrice weekly under same-sex observation for drug screening. In the seventh week of treatment, participants began 12 weeks of voucher-based contingency management (CM) to reinforce abstinence from heroin and cocaine; participants could receive up to $2310 in vouchers (exchangeable for goods and services) for urine specimens negative for cocaine, opiates, or both, as described previously [citation removed for masked review].

During the 12 weeks of CM, participants attended weekly individual therapy sessions based on the CBT manual for cocaine addiction published by the NIDA (Carroll, 1998). Counselors had been trained in delivery of the manualized CBT, which included regular verification of treatment fidelity by evaluation of taped sessions. At each session, the participant was given a written homework assignment to be completed daily for 7 days, and the counselor reviewed the homework from the previous week with the participant. At the end of 20 weeks, participants could choose to transfer to a community treatment program or receive an 8-week methadone taper.

2.3. Study design and experimental interventions

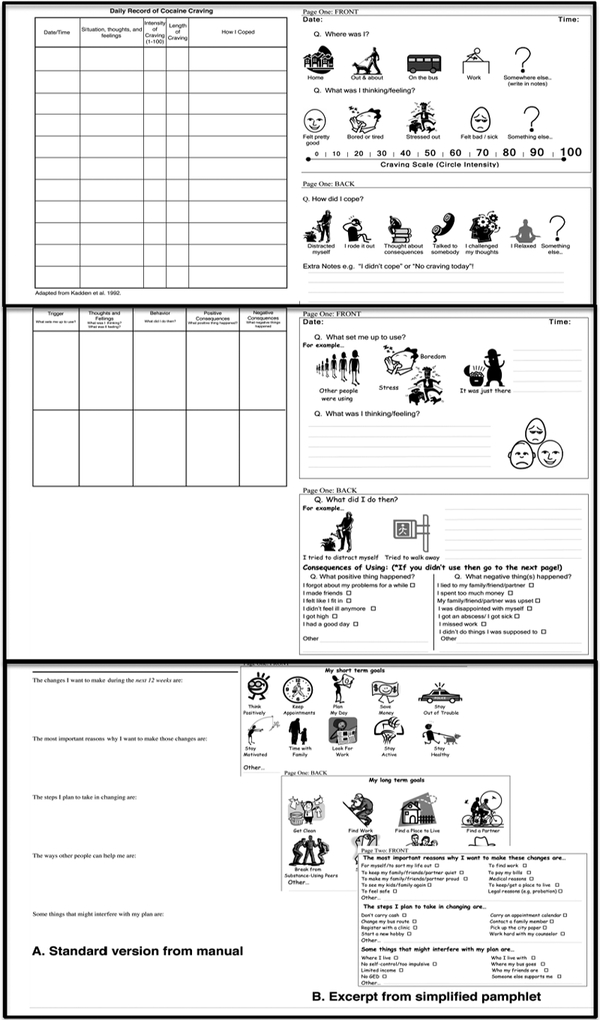

There were four conditions (simplified or standard homework, with or without electronic reminders). Participants were scheduled to undergo the four conditions during four three-week blocks, which ran consecutively in a factorial 2×2 counterbalanced Latin-square design. Random assignment to a treatment sequence was done by one of the investigators using a random-number table. Within each three-week block, participants completed three 7-day homework assignments: a functional analysis of cocaine use, a daily record of craving and coping, and a treatment-goals exercise. The standard versions of the homework were drawn directly from the NIDA toolbox (Carroll, 1998). The simplified versions were derived from the standard homework with pictorial representations of the concepts in pocket-sized pamphlets. In the simplified versions, possible answers to open-ended questions were provided in checkbox form, along with space for participants to write additional answers. Standard homework and excerpts of the simplified versions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Standard homework (left), from the NIDA CBT manual (Carroll, 1998) and excerpts from simplified homework (right): Top panel: Daily record of craving and coping homework; Middle panel: Functional analysis of cocaine use; Bottom panel: Treatment-goals exercise.

From week 4 to week 25, participants carried electronic diaries (PDAs; Palm Zire and Palm Zire 21, Palm Inc, Sunnyvale, California) to provide EMA data on their activities, moods, and behaviors in 3 daily randomly prompted entries, as previously described [citation removed for masked review]. In each random-prompt entry, participants were asked about their exposure (“Within the past hour…”) to putative triggers of craving and lapse based on a published taxonomy of relapse triggers (Heather, Stallard, & Tebbutt, 1991; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). The trigger items were conceptualized as negative-affect triggers (“I felt bored,” “I felt angry or frustrated,” “I felt worried, anxious, or tense,” “I felt sad,” “I felt others were being critical of me,” “I felt ill, in pain, or uncomfortable”); drug-cue triggers (“I saw heroin or cocaine,” “Someone offered me heroin or cocaine,” “I handled $10 or more in cash”), temptation-related triggers (“I wanted to see what would happen if I used just a little heroin or cocaine,” “Out of the blue, I felt tempted to use heroin or cocaine”), and a positive-affect trigger (“I was in a good mood and felt like celebrating”). In the same random-prompt entries, participants were asked to rate their stress, cocaine craving, and heroin craving “right now” on a four-point scale (NO!!, no??, yes??, YES!!).

In 6 of the 12 weeks of CBT, participants received daily, automated reminders to complete the homework assignments delivered by the PDAs.

At each CBT session, the counselor recorded whether the participant had completed that week’s homework. As several authors have pointed out, the proportion of homework assignments completed does not convey all aspects of adherence; it is also important to determine how well the homework was completed (Dozois, 2010; Kazantzis, et al., 2010). Therefore, counselors were trained to rate the quality of each completed assignment, and the enthusiasm and understanding it reflected. The two latter variables were included as proxy measures of the acceptability (Tompkins, 2002) and suitability (Conoley, et al., 1991; Conoley, et al., 1994). Raters were blinded with respect to EMA reminders but could not be blinded with respect to simplification, as this was apparent from the physical appearance of the homework.

2.4. Data analysis

Rates of homework completion were analyzed with repeated-measures logistic regression (SAS Proc Glimmix). The binary dependent variable was whether the participant completed the homework assignment prior to the session. The time-varying predictors were homework type (standard vs. simplified) and electronic prompting (present versus absent). The model also controlled for the theme of the homework (“functional analysis,” “treatment goals,” or “daily record of craving”) and percentile score on the PPVT. (PPVT percentile, rather than Shipley IQ, was used as the control variable because the simplified homework had been specifically designed to be accessible to individuals with limited verbal abilities.) A variance-components error structure provided the best fit to the data by Akaike’s Information Criterion.

Counselors’ numerical ratings of quality, enthusiasm, and understanding (on a 6-point scale) were analyzed similarly, using repeated-measures linear regression (SAS Proc Mixed) because the dependent variable was continuous rather than binary.

To assess EMA reports and drug screens as a function of homework type, we coded the data as follows. Each EMA report (typically several per participant per day) and each urine drug screen (three per participant per week) from the 12-week intervention was classified as having occurred during a week of standard homework or a week of simplified homework—unless the participant did not do the homework for that week, in which case the week was considered a “homework not done” week, regardless of homework type. Thus, for these analyses, “homework condition” fell into three categories rather than two. The categories applied to entire weeks rather than individual days because, although homework was supposed to have been completed daily, we could not determine whether some days’ homework sheets were “back-filled” (Stone, Shiffman, Schwartz, Broderick, & Hufford, 2002); we could only establish whether a given week’s assignment was done at all. Our assumption was that exposure to a given homework assignment—which began in the counseling session in which it was assigned—would have a diffuse effect on cognition and mood throughout the week, if it had any effect at all.

The EMA data were then analyzed in repeated-measures linear regression models (SAS Proc Mixed). In the first set of EMA analyses, the dependent measures were ratings of stress, cocaine craving, and heroin craving “right now” at random moments throughout the day. The time-varying predictor was homework condition (simplified, standard, or not done). The second set of EMA analyses focused solely on the same ratings of cocaine craving “right now” (because cocaine craving and use were the focus of the intervention). The two time-varying predictors were homework condition (simplified, standard, or not done) and the presence or absence of past-hour exposure to triggers, as reported in the same EMA entry. The interaction of the two predictors was tested to examine whether craving in response to triggers would differ across homework conditions. Effect sizes are given as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Thrice-weekly urine results for cocaine were analyzed similarly in a Glimmix model. The binary dependent variable was negative or positive urine. The time-varying predictor was homework condition (simplified, standard, or not done).

To test whether craving decreased during the study in the whole sample, we ran additional Proc Mixed models on EMA reports over three time periods: before CBT (weeks 4–6), during CBT (weeks 7–18) and after CBT (weeks 19–25) CBT, separately modeling instances in which drug cues or negative triggers had been present or absent.

Our target for statistical power was to have at least 80% power to detect a 20% increase in the rate of homework completion in any pairwise comparison between conditions; this required complete data from at least 21 participants. We enrolled slightly more than twice that number, anticipating dropout.

In all analyses, the criterion for statistical significance was p ≤ .05, two-tailed, with trends noted at p ≤ .10.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive characteristics

Because the study used a 2×2 Latin-square design, it was only possible to evaluate the participants who sampled all four CBT/prompting conditions. A total of 49 participants were enrolled in the study; of these, 27 participants were considered evaluable and included in the analyses. The 22 participants considered nonevaluable dropped out after a mean of 37.7 days (SD = 42.4, median = 20) and 1 session of CBT (SD = 2.2, median = 0). However, they did not differ from the 27 evaluable participants on any of the baseline demographic characteristics listed in the next paragraph.

Of the 27 evaluable participants, 56% were male. Self-reported race was 56% Caucasian and 44% African American. Upon enrollment, 56% of the participants had never been married and 22% were divorced, with the remaining portion being split equally between those who had been separated or widowed. Fourteen (52%) participants were employed full-time, 3 (11%) were employed part-time, and 10 (37%) were unemployed at study enrollment. The mean age was 40 years (SD = 9; range 18 – 53). Over half (81%) of the sample had at least a high-school diploma or GED. The mean percentile score on the PPVT was 31.5 (SD = 23.5, median = 25, range 1–75); this score is equivalent to receptive vocabulary knowledge of 18.5 years. Sample mean Shipley-estimated full-scale IQ was 94.2 (SD = 10.4, median = 93, range 80–111). The PPVT percentile scores were strongly correlated with Shipley-estimated full-scale IQ scores (r = .75, p < .0001).

3.2. Homework completion and quality

A total of 287 homework assignments were given (mean 10.6 per participant). Due to errors in implementation, some participants received more or fewer days of a particular condition than intended. Our analysis is of treatment as it was actually delivered.

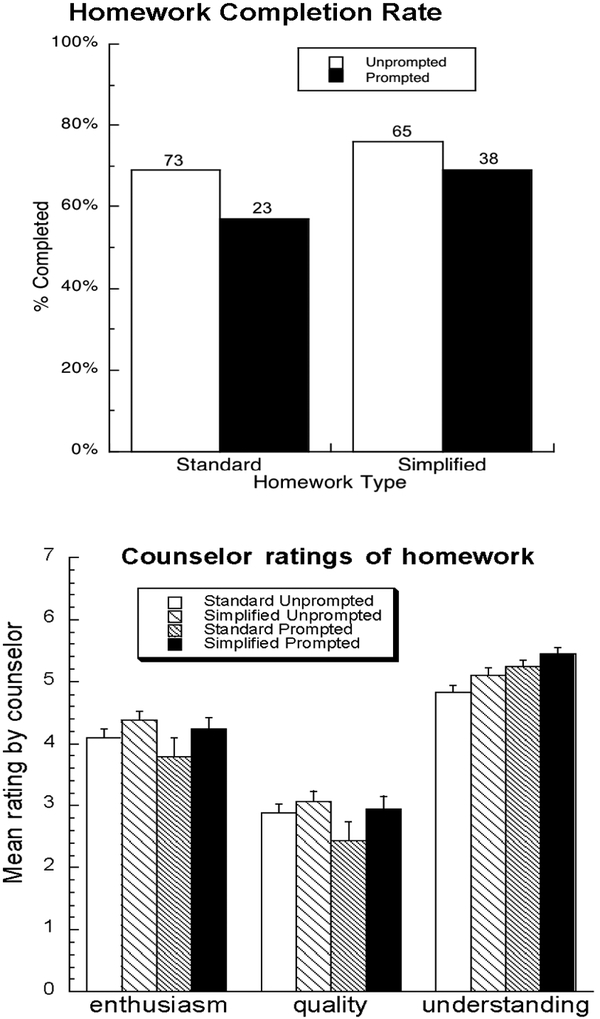

The percentage and number of completed homework assignments for the simplification and reminder interventions are shown in Figure 2 (top panel). Completion rates for simplified homework (73%) appeared slightly higher than those for standard homework (66%), but in our regression models, the main effect of simplification were not significant, OR = 1.48 (95% CL 0.84 to 2.63). The electronic prompting appeared, if anything, to decrease completion rates (from 72% to 64%), but again, the main effect of prompting was not significant, OR = 0.64 (95% CL 0.36 to 1.13).

Figure 2.

Percentages of homework assignments completed (upper panel) and mean counselor ratings of homework on enthusiasm, quality, and understanding (lower panel). Small numbers above bars in upper panel indicate the total number of homework assignments. Error bars in the lower panel indicate standard errors.

Mean ratings of enthusiasm, quality, and understanding, as assessed by the counselors, are shown in Figure 2 (lower panel). In our regression models, there were trends (p < .10) for the simplified homework tasks to be rated higher by counselors in terms of participants’ enthusiasm and understanding (Table 1). Unexpectedly, electronically prompted homework was also rated higher in terms of participants’ understanding (p < .02), though it tended to be rated lower in terms of quality (p < .09). Inspection of the means (Figure 2) suggests that quality and enthusiasm ratings were especially low when standard homework was paired with electronic reminders, though this was not reflected in significant Simplification x Prompting interactions. Homework theme had no significant effect on any of the outcome measures.

Table 1.

Main Effects and Interactions of Two CBT Homework Interventions (CBT and Electronic Prompting) on Measures of Adherence and Quality

| Intervention | Completion ratea | Enthusiasm | Quality | Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplification | F(1,26) = 2.04, n.s. | F(1,26) = 3.40, p < .08 | F(1,26) = 2.70, n.s. | F(1,26) = 3.19, p < .09 |

| (main effect) | ||||

| Prompting | F(1,23) = 2.66, n.s. | F(1,23) = 1.60, n.s. | F(1,23) = 3.15, p < .09 | F(1,23) = 7.29, p < .02 |

| (main effect) | ||||

| Simplification | F(1,14) = 0.30, n.s. | F(1,14) = 0.30, n.s. | F(1,14) = 0.97, n.s. | F(1,14) = 0.01, n.s. |

| x Prompting | ||||

| Homework theme | F(2,52) = 1.30, n.s. | F(2,52) = 0.20, n.s. | F(2,52) = 0.07, n.s. | F(2,52) = 0.81, n.s. |

| (control term) | ||||

| PPVT percentile | F(1,25) = 1.32, n.s. | F(1,25) = 0.23, n.s. | F(1,25) = 15.15, p < .001 | F(1,25) = 10.45, p < .004 |

| (control term) |

F tests for completion rate are from the same Glimmix model that produced the odds ratios given in the text.

PPVT percentile score (Table 1) was positively related to ratings of homework quality (b = .015, SEM = .004; p < .001) and understanding (b = .008, SEM = .003; p < .004), though not to ratings of enthusiasm or to homework-completion rates. In additional analyses (not shown), we found no evidence that the simplified homework differentially increased homework-completion rates or quality/enthusiasm/understanding ratings as a function of PPVT percentile score, or that homework completion and quality were associated with basic demographic variables (such as age, race, and education).

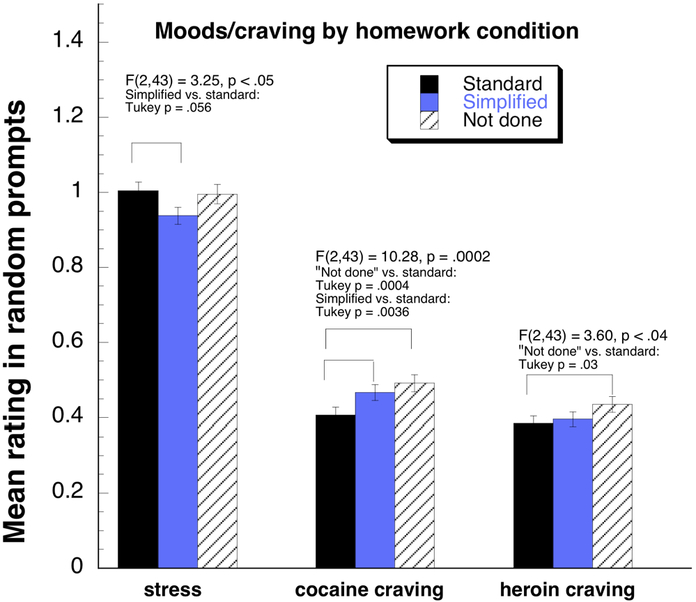

3.3. Homework, stress, craving, and drug-use triggers

For the 26 of 27 participants on whom data were available, the mean rate of response to random prompts was 78% (SD 16 SD). EMA ratings of stress and drug craving differed between weeks in which participants completed standard or simplified homework or failed to complete the homework (Figure 3). Specifically, stress ratings tended to be lower during weeks of simplified homework than during weeks of standard homework (Tukey p=.056). Yet cocaine craving was significantly lower during weeks of standard homework than during weeks of simplified homework (p=.004), or weeks in which the homework was not done (Tukey p=.0036). Similarly, heroin craving was significantly lower during weeks of standard homework than during weeks in which the homework was not done (Tukey p=.03).

Figure 3.

Mean ratings of stress, cocaine craving, and heroin craving in weeks in which standard homework or simplified homework was completed or assigned homework was not done. Ratings were collected on electronic diaries at randomly prompted times during participants’ waking hours.

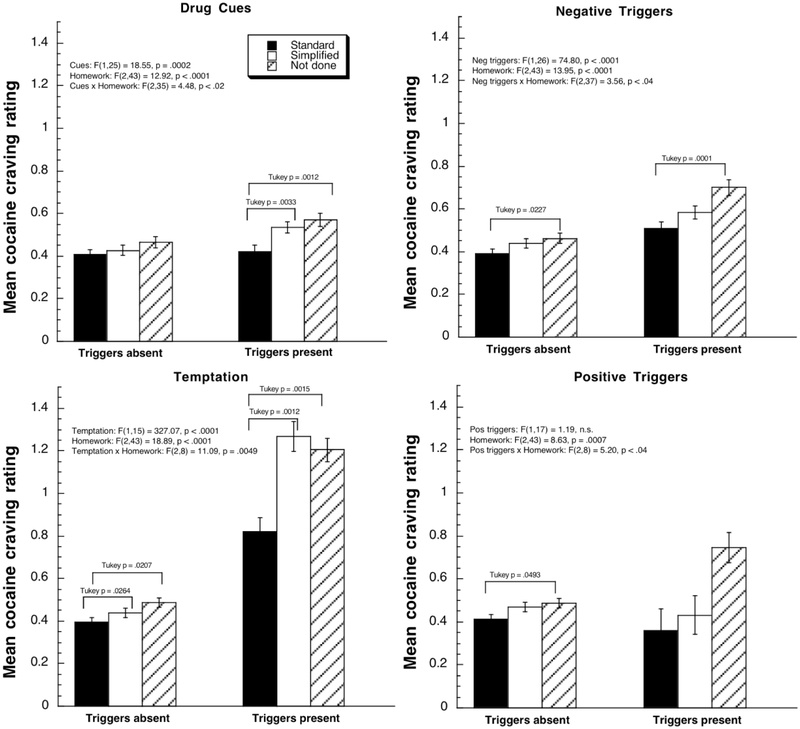

The analyses above reflect all ratings of stress and craving during the weeks of interest. Because CBT specifically included the teaching of skills for responding effectively to drug-use triggers, we conducted additional analyses to assess cocaine-craving ratings as a function of past-hour exposure to triggers (reported at the same time as the craving). These analyses all returned significant interactions between the presence/absence of triggers and homework type (reported in Fig. 4), justifying the further analysis of simple effects.

Figure 4.

Mean ratings of cocaine craving in the presence of four types of putative drug-use triggers: drug cues, negative affect, temptation to use, and positive affect, reported in random prompts in the weeks in which standard homework or simplified homework was completed or assigned homework was not completed. Ratings were collected on electronic diaries at randomly prompted times during participants’ waking hours. Tukey comparisons between the Triggers Absent and Triggers Present conditions are not shown in the figure but are reported in the Results section.

First, as expected, cocaine craving was significantly higher (Tukey p=.002) in the presence of drug cues (e.g., seeing or being offered drugs) (Figure 4, upper left panel); that increase with cues was significant during weeks of simplified homework (Tukey p = .0024) and when the homework was not done (Tukey p = .0121), but not during weeks of standard homework (Tukey p = .99).

Also as expected, cocaine craving was significantly higher (p<.0001) in the presence of negative-affect triggers (e.g., feeling angry, worried or sad) (Figure 4, upper right panel); the increase with negative affect was significant in each of the three homework conditions (Tukey p < .0001 for “Not done,” p =.0002 for Simplified, p =.0063 for Standard). In addition, craving was significantly lower during weeks of standard homework than during weeks when the homework was not done, whether negative-affect triggers were absent (Tukey p=.0227) or present (Tukey p=.0001).

Also as expected, in the presence of temptation triggers (e.g., cravings “out of the blue”), cocaine craving was significantly higher (p<.0001) (Figure 4, lower left panel); the increase with temptation was significant in each of the three homework conditions (Tukey p < .0001 for “Not done” and Simplified,.0002 for Standard). Both in the absence and presence of temptation, craving was significantly lower during weeks of standard homework than during weeks of simplified homework (absent Tukey p=.0264; present Tukey p=.0012) and during weeks when the homework was not done (absent Tukey p=.0207; present Tukey p=.0015).

Finally, the presence of a positive trigger (good mood) had no significant main effect on craving, but did interact with homework condition (Figure 4, lower right panel)—mostly reflecting an increase in craving with good mood only during weeks when the homework assignment was not done (Tukey p < .05).

3.4. Urine-verified cocaine abstinence

In a Glimmix analysis, there was no difference in cocaine abstinence as a function of homework condition. Model-adjusted percentages of cocaine-negative urines were 66% (SEM 5%) during weeks of standard homework, 66% (SEM 6%) during weeks of simplified homework, and 62% (SEM 6%) during weeks when the homework assignment was not done, F(2,41) = 0.49, p = .62.

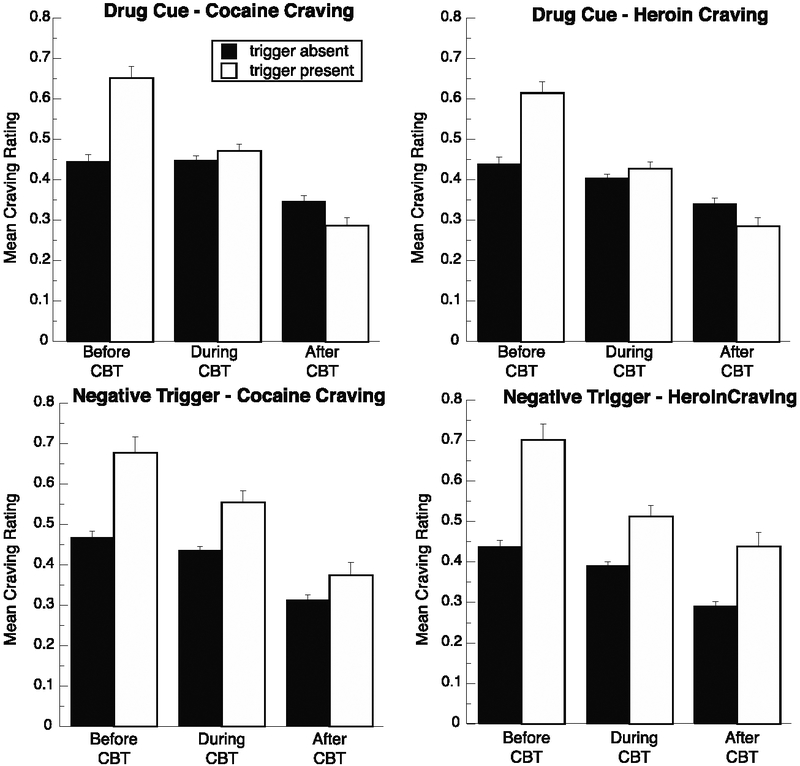

3.5. EMA reports before, during, and after CBT

In these analyses, intended simply to show that craving decreased during the study, we included all participants who attended at least one CBT session (n=35). They provided a total of 9,316 random-prompt EMA entries, of which the proportions corresponding to each trigger condition were: cue exposure, 33%; negative-trigger exposure, 19%; temptation, 5%; good mood, 4%; no trigger present 54%. The figures for trigger-present are non-exclusive, and only 0.7% of reports (69/9316) involved exclusively temptations and/or good-mood triggers. Fig. 5 shows levels of craving for cocaine (left) and heroin (right) as a function of the presence or absence of the two major classes of triggers, drug cues (two upper panels) and negative-mood triggers (two lower panels). In the presence of either drug cues or negative-mood triggers, both cocaine and heroin craving decreased linearly over the three time periods (all eight p values .007 or lower), with the eight effect sizes ranging from reffect=.36 to reffect=.82 (median .65).

Figure 5.

Changes across the study, for the whole sample, in ratings of cocaine craving and heroin craving in the presence or absence of two types of putative drug-use triggers drug cues and negative affect, reported in random prompts before, during, and after CBT/CM. Significant linear decreases occurred across the three time bins for each of the eight dependent measures, supporting the overall effectiveness of the treatment as a whole.

4. Discussion

We attempted to increase completion of therapeutic homework assignments through a combination of electronic reminders and simplification of content. For homework simplification, there was a (non-significant) trend toward more completion; for electronic reminders, there was a (non-significant) trend in the opposite direction. We also investigated whether homework simplification would improve engagement, in terms of counselor ratings of understanding, enthusiasm, and quality. There were (non-significant) trends toward higher ratings of enthusiasm and understanding. EMA showed that cocaine and heroin craving decreased significantly during treatment, suggesting that our CBT/contingency management intervention was effective (discussed below).

Our homework simplification seemed to have little or no effect on daily-life stress and drug craving as assessed by EMA. Although stress was higher during weeks of standard homework, cocaine craving was lower. More specifically, exposure to drug cues (such as seeing or being offered drugs) in the natural environment was associated with acute increases in cocaine craving during weeks of simplified homework but not during weeks of standard homework. (No such difference was seen with negative-affect triggers and temptation triggers; they were associated with acutely increased cocaine craving regardless of homework condition.) These data, though not conclusive, are consistent with a buffering effect of standard homework on reactivity to drug cues. One possible explanation is that the standard homework required a greater depth of processing that produced accordingly larger effects.

We did find differences in daily-life cravings during weeks when homework was or was not completed as assigned. However, unlike the “standard homework” and “simplified homework” conditions, which were experimentally assigned, the “homework not done” condition reflects self-chosen periods of non-adherence by participants, so differences in the EMA data cannot be interpreted causally. For example, higher cocaine craving during weeks of failure to do homework could reflect a protective effect of homework on craving, an inability to attend to homework when levels of craving or stress were high, or an unmeasured third variable that drove homework adherence down and craving up. As simplified and standard homework assignments did not differ significantly in completion rates, the question of the direction of causality cannot be resolved by reference to different levels of stress or craving associated with these two conditions.

The absence of a homework effect on rates of cocaine-negative urine specimens was largely expected. Several studies have shown that the effects of CBT on cocaine use do not become detectable until 6 to 12 months after CBT ends (Carroll et al., 1994; Epstein, et al., 2003). The main goal of our interventions was to increase homework completion during CBT; we did not hypothesize an immediate effect of homework type on rates of cocaine use.

Unexpectedly, electronically prompted homework was rated higher in terms of participants’ understanding: ratings of understanding for homework completed in the combined simplified/prompted condition were considerably higher than those for homework completed in the standard condition (Cohen’s d = 1.8). We know of no plausible mechanism for an effect of electronic reminders on homework understanding, so we hesitate to interpret this finding. Perhaps the electronic reminders were differentially effective in prompting completion for patients with better understanding of the homework. Ratings of homework quality and understanding were significantly associated with participants’ general verbal ability as assessed by the PPVT, but, contrary to our expectations, the simplified homework produced no differential improvement in those ratings for participants with the lowest PPVT scores.

One possible reason for the absence of effects of prompting is that the automated reminders needed to be more frequent or more salient. It should also be noted that this study was done in the context of an EMA study in which the participants were carrying and responding to PDA prompts to answer questions three times daily at random times throughout the study. Though the questions were not explicitly intended to prompt homework completion, it is possible that they served as reminders to a degree that masked any beneficial effects. Some patients may have found the additional homework prompt more of an annoyance than a helpful reminder.

The behaviors assessed in this study were probably not affected to any appreciable degree by the use of EMA—i.e., by unwanted “reactivity” to the assessment (Hufford, Shields, Shiffman, Paty, & Balabanis, 2002; Litt, Cooney, & Morse, 2000). Even if reactivity occurred, it would be spread across our four counterbalanced homework conditions and would not confound the outcomes of interest.

The effect of our homework simplification may have been limited by an inadequate “dosage.” That is, the homework may have needed further simplification or to be applied for a longer duration of time. It is also possible that some beneficial effects of the simplified homework were lost due to the necessity of standardizing the conditions and following a manualized treatment protocol. Within CBT, a well-thought-out homework exercise is usually one that has been “tailored to the individual patient, set collaboratively, and devised according to the content and goals of the session” (Beck, 1995). Homework tends to emerge naturally from the therapeutic discussion, and, as therapy progresses, patients are expected to take the lead in devising their own assignments. Unfortunately, this sort of individualized treatment does not lend itself well to experimental investigation, though it is certainly possible to conduct a study comparing standardized and individualized homework formats. Nevertheless, the usefulness of homework simplification as a tool is supported in that the results were in the predicted direction. Indeed, these effects would be considered significant if we had taken advantage of the a priori predictions and used one-tailed tests.

Another possibility is that our interventions need to be qualitatively different. A mobile intervention, for this population, may need to go beyond a reminder beep and incorporate interactive elements; interactive electronic treatments have been effective on desktop platforms (Bickel, Marsch, Buchhalter, & Badger, 2008). Our simplification of the homework may have had any of several unintended effects. For example, the preponderance of checkbox answers may have inadvertently encouraged rote responding, though this would not explain the absence of an improvement in completion rates. The cartoon format, intended to engage participants at a cognitively appropriate level (Conoley, et al., 1991), may have looked inappropriately simplistic to some participants. We also note that while it is a reasonable assumption that the use of pictures and checkboxes makes for simpler completion than questions requiring a written answer, this has not actually been demonstrated for the materials used here.

One clinical implication of our study is that the findings provide empirical support for the suitability of CBT across demographic groups. Homework completion and quality were not associated with basic demographic variables (such as age, race, and education). These results are consistent with prior findings (Carroll, et al., 2005; Gonzalez, Schmitz, & DeLaune, 2006; Leung & Heimberg, 1996). Another clinical implication of our study is that therapists might consider personalization and possibly simplification of homework for their patients with cognitive impairment, but that these modifications could be ineffective or even backfire under some circumstances.

The results of this study should be interpreted in view of several limitations. First, the sample size was smaller than anticipated, because a high proportion of participants withdrew very early in the course of treatment, and factors influencing homework completion can logically only come into play with participants for whom homework has been assigned. Nevertheless, even with the low n, the study was only slightly underpowered (70%) for the detection of a medium effect size (d=0.5) in a two-tailed test. The small sample size does, however, limit the interpretation of some of the negative results because we were unable to investigate potential contamination across trial blocks. The Latin square design introduces the possibility of carry-over effects between conditions, which somewhat weakens the power of the study; but there were insufficient participants to investigate this issue statistically. Second, we do not have measures of some exogenous variables that may be related to homework compliance, such as client acceptance of treatment rationale and readiness to change. Third, we recruited our sample from an urban setting and we used some medical exclusions, so the results may not generalize to national samples in terms of economics or chronic diseases (e.g., hepatitis, HIV, diabetes). Future work with nationally representative samples and treatment-readiness measures may provide more insight into the processes by which homework difficulty, cognitive ability, and enthusiasm/motivation contribute to CBT acceptability and success in substance-use disorders. Fourth, we did not assess participants’ subjective responses to the interventions. Therefore, we cannot verify our speculations about reasons for their relative ineffectiveness. In ongoing work, we are developing mobile interventions that are more directly interactive, and we will be incorporating participant feedback into the processes of development and evaluation. Finally, our study lacked a no-treatment condition, so we cannot be certain that the clinical gains observed for the sample as a whole were attributable to the intervention. In the absence of a control group, the behavioral changes recorded could equally reflect either the passage of time or a practice effect. However, the decreases in craving were substantial (with a median effect size of r = .65), and changes of this magnitude are not an inevitable concomitant of several weeks of methadone maintenance (Fareed et al., 2011).

In spite of the aforementioned limitations and the null results, the strength of this work is its use of real-time data collection strategies. Additionally, our findings suggest that future research on treatment compliance among methadone-maintained substance users may require higher “doses” of psychotherapeutic interventions.

Practitioner Points.

Our simplifications of homework assignments for cognitive-behavioral therapy were mostly ineffective, or even counterproductive, perhaps because they did not engage sufficient depth of processing or because they were perceived as too simplistic.

Our reminder beeps for homework were mostly ineffective, or even counterproductive, suggesting that mobile electronic interventions for substance-use disorders may need to be more interactive.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, Liu X, Bisaga A, & Nunes EV (2006). Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 81(3), 313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich E, Nunes E, & Hasin DS (2003). Cognitive impairment, retention and abstinence among cocaine abusers in cognitive-behavioral treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 71(2), 207–211. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00092-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Crino R, Hunt C, Lampe L, & Page A (1994). The Treatment of Anxiety Disorders: Clinician’s Guide and Patient Manuals. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1995). Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush JA, Shaw BF, & Emery G (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Wright F, Newman C, & Liese B (1993). Cognitive Therapy of Substance Abuse. New York: Guilford Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA, Buchhalter AR, & Badger GJ (2008). Computerized behavior therapy for opioid-dependent outpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(2), 132–143. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn I, & Twaddle V (1996). Cognitive Therapy in Action. London: Souvenir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolla KI, Rothman R, & Cadet JL (1999). Dose-related neurobehavioral effects of chronic cocaine use. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 11(3), 361–369. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.3.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM (1998). Treating Cocaine Addiction: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, & Ball SA (2005). Practice makes progress? Homework assignments and outcome in treatment of cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 749–755. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Onken LS (2005). Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(8), 1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, & Gawin F (1994). One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence. Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(12), 989–997. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conoley CW, Conoley JC, Ivey DC, & Scheel MJ (1991). Enhancing consultation by matching the consultee’s perspectives. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69(6), 546–549. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1991.tb02639.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conoley CW, Padula MA, Payton DS, & Daniels JA (1994). Predictors of client implementation of counselor recommendations: matching with problem, difficulty level, and building on client strengths. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(1), 3–7. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.41.1.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Detweiler JB, & Whisman MA (1999). The role of homework assignments in cognitive therapy for depression: potential methods for enhancing adherence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6(3), 267–282. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.6.3.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sclafani V, Tolou-Shams M, Price LJ, & Fein G (2002). Neuropsychological performance of individuals dependent on crack-cocaine, or crack-cocaine and alcohol, at 6 weeks and 6 months of abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 66(2), 161–171. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00197-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, & Marlatt GA (1998). Preventing relapse and maintaining change in addictive behaviors. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(4), 513–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00171.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJ (2010). Understanding and enhancing the effects of homework in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(2), 157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01205.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn LM (1997). Examiner’s Manual for the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 3rd edition Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Hawkins WE, Covi L, Umbricht A, & Preston KL (2003). Cognitive-behavioral therapy plus contingency management for cocaine use: findings during treatment and across 12-month follow-up. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(1), 73–82. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareed A, Vayalapalli S, Stout S, Casarella J, Drexler K, & Bailey SP (2011). Effect of methadone maintenance treatment on heroin craving, a literature review. J Addict Dis, 30(1), 27–38. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.531672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Schmitz JM, & DeLaune KA (2006). The role of homework in cognitive-behavioral therapy for cocaine dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol, 74(3), 633–637. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton C (2002). Psychosocial interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems. Journal of Mental Health, 11(4), 357–373. doi: 10.1080/09638230020023732 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Stallard A, & Tebbutt J (1991). Importance of substance cues in relapse among heroin users: comparison of two methods of investigation. Addictive Behaviors, 16, 41–49. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90038-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufford MR, Shields AL, Shiffman S, Paty J, & Balabanis M (2002). Reactivity to ecological momentary assessment: an example using undergraduate problem drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16(3), 205–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.16.3.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Deane FP, & Ronan KR (2000). Homework assignments in cognitive and behavioral therapy: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7(3), 189–202. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.7.2.189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Whittington C, & Dattilio F (2010). Meta-analysis of homework effects in cognitive and behavioral therapy: a replication and extension. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(2), 144–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01204.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, & Carroll KM (2010). Relationship of cognitive function and the acquisition of coping skills in computer assisted treatment for substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimhy D, & Corcoran C (2008). Use of Palm computer as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioural therapy with an ultra-high-risk patient: a case report. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 2(4), 234–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2008.00083.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AW, & Heimberg RG (1996). Homework compliance, perceptions of control, and outcome of cognitive-behavioral treatment of social phobia. Behavior Research and Therapy, 34(5–6), 423–432. doi: 10.1037/1053-0479.16.2.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Cooney NL, & Morse P (2000). Reactivity to alcohol-related stimuli in the laboratory and in the field: predictors of craving in treated alcoholics. Addiction, 95(6), 889–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9568896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Gordon JRE (1985). Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M, de Jesus M, Gorman JM, & Papp LA (2003). Standard and enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: two pilot investigations. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(1), 24–32. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200301000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA, Kazantzis N, Kassler DM, Baker KD, & Fletcher R (2008). Group cognitive behavioural therapy for depression outcomes predicted by willingness to engage in homework, compliance with homework, and cognitive restructuring skill acquisition. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 37(4), 199–215. doi: 10.1080/16506070801981240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Flammino F, Shoptaw S, Miotto K, Reiber C, et al. (2006). A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches for stimulant-dependent individuals. Addiction, 101(2), 267–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees CS, McEvoy P, & Nathan PR (2005). Relationship between homework completion and outcome in cognitive behaviour therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 34(4), 242–247. doi: 10.1080/1650607051001154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran J, Segal Z, Vallis T, Shaw BF, & Samstag L (1993). Assessing patient suitability for short-term cognitive therapy with an interpersonal focus. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 17(1), 23–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01172738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safran J, Vallis T, Segal Z, & Shaw BF (1986). Assessment of core cognitive processes in cognitive therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10(5), 509–526. doi: 10.1007/BF01177815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley WC (1940). A self-administering scale for measuring intellectual impairment and deterioration. Journal of Psychology, 9, 371–377. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1940.9917704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stenfert-Kroese B, Dagnan D, & Loumidis K (1997). Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, & Hufford MR (2002). Patient non-compliance with paper diaries. BMJ, 324(7347), 1193–1194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Lindsay W, & Willner P (2008). CBT for people with intellectual disabilities: emerging evidence, cognitive ability and IQ effects. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(1), 723–733. doi: 10.1017/S1352465808004906 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins MA (2002). Guidelines for enhancing homework compliance. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(5), 565–576. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse R, Tudway J, Look R, & Stenfert-Kroese B (2006). Adapting individual psychotherapy for adults with intellectual disabilities: a comparative review of the cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic literature. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(1), 55–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2005.00281.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P (2006). Readiness for cognitive therapy in people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(1), 5–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2005.00280.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, & Tomlinson S (2007). Generalisation of anger coping-skills from day-services to residential settings. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20(6), 553–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00366.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]