Abstract

This study examined how parental cultural orientations and family process are related among Korean immigrant parents (272 mothers, and 164 fathers, N=436) and how the relationship varies across fathers and mothers. Multiple scales were used to assess bilinear, multidimensional cultural orientation towards both the culture of origin and mainstream culture. The dimensions of language, identity, and cultural participation as well as the number of years living in U.S. were analyzed. The main findings include: (1) parents who maintain heritage culture orientation were more likely to preserve traditional parenting values and practices, (2) parental host culture orientation largely had no impact on traditional parenting but some elements of the host culture orientation were in fact associated with stronger endorsements of traditional parenting, (3) each dimension of acculturation differentially related to traditional parenting, and (4) significant relationships were more pronounced among parenting values than practices. These patterns were largely similar across mothers and fathers. Although some mixed findings suggest the complexity of the hypothesized relationships, the present study findings highlight the importance of bilinear and multidimensional acculturation and core vs. peripheral elements of culture in family process. Implications for practice and future research are discussed.

Keywords: Cultural orientation, Korean American family process, Korean immigrant fathers, Korean immigrant Mothers

In recent years, greater attention has been paid to differences in developmental contexts between minority and majority children and youth. For example, Garcia Coll and her colleagues’ seminal integrative model of development of minority children (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Garcia Coll & Pachter, 2002) argues that cultural orientation, social class, and minority status place unique, specific demands on minority parenting and youth development. In their integrative model, acculturation, the process through which culture changes, is posited to influence family process, which includes parenting values, beliefs and goals. Acculturation is a particularly salient issue for Asian American youth and their families, and this paper expands Garcia Coll et al.’s theorized relationship between acculturation and family process by integrating recent developments and advancement in the literature.

Acculturation was once thought of as a unilinear process in which immigrants discard their heritage culture and wholly assimilate to the host culture over time (e.g., Gordon, 1964). Recent studies have validated a bilinear model of acculturation that accounts for the acculturating individual’s ability to preserve their heritage culture while concomitantly adopting dimensions of a new culture (Yoon et al., 2013). In addition to being at least bilinear, acculturation is also selective and disparate across dimensions of culture. Core elements of the heritage culture such as internal and psychological dimensions like racial-ethnic identity, may be preserved while peripheral elements, i.e. external and behavioral dimensions such as media and food consumption, can be readily replaced with those of the host culture (Laroche, Kim, Hui, & Joy, 1996).

Although usually perceived as one of the successfully settled immigrant groups, Koreans in the U.S. present a mixed picture. For example, they have a lower median income than the average Asian Americans, and the lowest median income among the six most populous Asian subgroups (Pew Research Center, 2013). Koreans also have, along with the Vietnamese, the largest share of adults in poverty among Asian Americans (Pew Research Center, 2013). While Korean Americans are more integrated in U.S. society than many smaller Asian American subgroups, they have a larger share of limited English proficiency and linguistically isolated households than the Asian American average (Center for American Progress, 2015). Further, Korean Americans report the most dissimilarity, and therefore residential segregation, from Blacks and Hispanics among the five largest Asian American subgroups (Iceland, Weinberg, & Hughes, 2014) and are the most likely of all Asian American subgroups to have mostly or all their friends share the same ethnic heritage (Pew Research Center, 2015). This relative cultural and social isolation is congruent with high rates of acculturative stress reported among Korean Americans (Noh, Kaspar, & Wickarama, 2007). Published and ongoing studies indicate that Korean American youth experience marked levels of emotional problems, and several scholars have attributed such youth difficulties at least in part to intergenerational acculturation differences with their parents (e.g., Cho & Bae, 2005; E. Kim & Cain, 2008; Yeh, 2003). Yet, it is too simplistic to conclude that immigrant parents are wholesale more resistant to acculturation than their children (Telzer, 2010). Rather, there may be substantial variability in texture among immigrant parents’ orientation towards mainstream culture, and an explicit and empirical examination of immigrant parents’ orientation towards both host and heritage cultures and, subsequently, how orientation shapes family process, is needed.

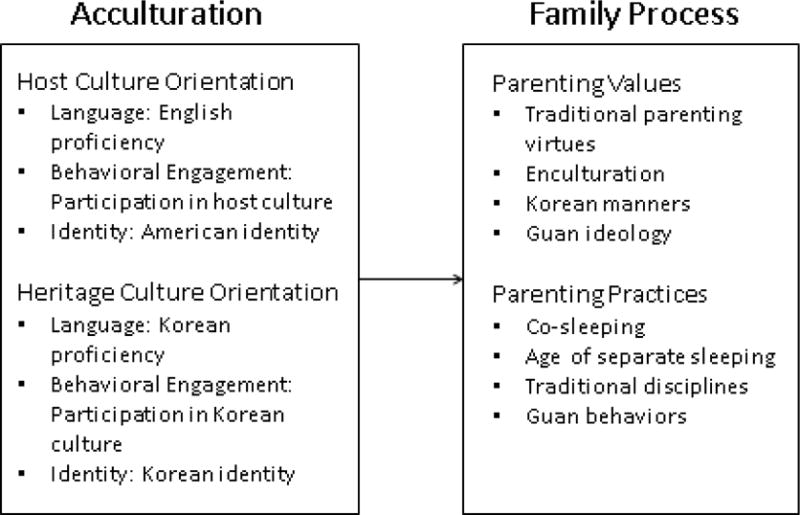

The present study, using recently developed indigenous measures of Korean and Chinese American family process, examines how bilinear and multidimensional cultural orientations are associated with traditional parenting values and practices among Korean immigrant parents. Garcia Coll et al.’s work on the distinct ecology of ethnic and minority parenting (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Garcia Coll & Pachter, 2002) informs the relationship between acculturation and family process. We further expound on recent scholarship capturing the process of acculturation as bilinear and multidimensional and, lastly, lean on Darling and Steinberg’s model (1993), further discussed below, to organize several indigenous family process variables into parenting values and practices. The conceptual model is summarized in Figure 1. Additionally, this study investigates whether the associations proposed by the conceptual model differ across mothers and fathers by explicitly testing moderating effects of parent gender.

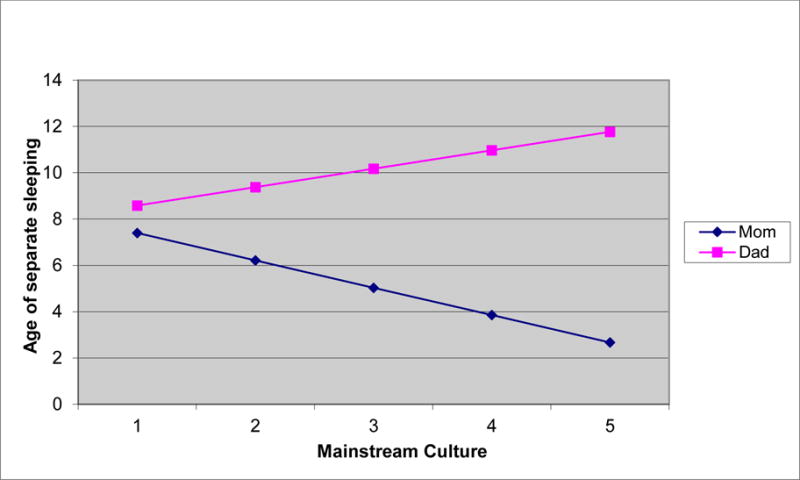

Graph 2.

Interaction plot of engagement in mainstream culture on the age of separate sleeping by parent gender

Bilinear and Multidimensional Cultural Orientations

Although acculturation is now commonly understood as a complex, dynamic, and at least bilinear process, with only a few exceptions (e.g., Benner & Kim, 2009; Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, Kim, & Kim, 2017; Ying, Lee, & Tsai, 2000), it is not yet common to empirically examine it as such. In this paper, we use the term cultural orientations to signify the bilinear nature of the process in which a cultural minority can simultaneously possess multiple repertoires of different cultures and demonstrate equal competence in multiple cultural settings. Specifically, we examine the concomitant cultural orientations to the host culture (host culture orientation) and to the heritage culture (heritage culture orientation) as independent constructs while acknowledging the complex interrelations between the two.

Cultural orientation toward both one’s heritage culture and host culture can coexist in various forms of biculturalism (Nguyen & von Eye, 2002). Although some argue that the acculturation process is orthogonal, where identification with any culture is essentially independent of identification with any other culture, an individual’s orientation to the mainstream culture has been associated with change in the individual’s orientation to the heritage culture and vice versa (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky & Kim, 2013). Thus, different cultural orientations (i.e., host and heritage culture orientations) are at least moderately and inversely correlated (Nguyen & von Eye, 2002) and should be examined simultaneously to better capture the interplay of cultural orientations.

In addition to being at least bilinear, acculturation is also multidimensional. While researchers often combine or use interchangeably different dimensions of cultural orientation, such as language competence, behavioral participation in cultural activities, and racial-ethnic identity, these dimensions are distinct and independent aspects of acculturation. For example, one’s inability to speak their heritage language does not necessarily mean a low level of racial-ethnic identity. More importantly, different dimensions of cultural orientation are differently related to family process variables such as youth perception of family process. Specifically, when examined simultaneously and as distinct constructs, racial-ethnic identity and behavioral enculturation, but not heritage language competence, helped parent-child bonding and increased youth perception of parental affection (Choi et al., 2017). Nonetheless, it is not infrequent that one aspect of cultural orientation is selected as a proxy for the whole concept, which may contribute to inconsistency in findings on acculturation. It is both scientifically more refined to specify which aspects of cultural orientation are associated with related constructs and more effective in guiding interventions.

Core vs. Peripheral Elements of Multidimensional Culture

Culture, as a broad context of family and society, encompasses, among other things, language, identity, knowledge, ideal values, foods, parenting behaviors and values. Family process is embedded in a larger context of culture and the relationships between acculturation and family process are likely to be interactive (Garcia Coll & Pachter, 2002). The multiple dimensions of culture may be categorized into “core” and “peripheral” dimensions (Rosenthal & Feldman, 1992). Core dimensions are psychological, internal and value-related. Peripheral dimensions are behavioral and external. Core dimensions are less likely than peripheral ones to change over time and changes in one dimension can happen independently of changes in other dimensions (Laroche, Kim, Hui, & Joy, 1996). It follows that multidimensional acculturation itself has core and peripheral dimensions. Core elements include societal values and racial/ethnic identity and peripheral elements include language competence and external cultural behaviors. Adoption of the external behaviors and language of a host culture (i.e., peripheral elements) does not necessarily reflect the extent to which a person endorses the core societal values of the host culture (Mariño, Stuart, & Minas, 2000).

Relative to cultural dimensions such as language, knowledge and cultural practices (e.g., foods and media specific to a culture), family process, comprised of the values, practices, and relationships among family members, is one of the core dimensions of culture and particularly resistant to change. Darling and Steinberg (1993) organize a panoply of family process constructs into several related but distinct clusters such as parenting goals and values, parenting style, and parenting practices. They further theorize that cultural differences emerge mostly through parenting values and practices and that parenting goals and values determine parenting practices. Family process, too, can be characterized by core versus peripheral elements. Within family process, parenting values would be core elements and parenting practices and behaviors are peripheral ones. Accordingly, parenting practices and behaviors may change before central values regarding childrearing. Thus, it is not incompatible to find that Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean immigrant parents resist acculturative pressure and preserve their traditional and core parenting values while also adopting several new cultural traits and parenting practices (Choi, et al., 2013; Kibria, 2002; Louie, 2004). Similarly, Japanese Americans, the majority of whom are third or later generations of immigrants, have preserved traditional core childrearing values notwithstanding their unparalleled, among Asian Americans, assimilation to the mainstream culture in other dimensions such as language (Greenfield, 1994). Among non-Western immigrants such as Asian immigrants, family process is partially or fully modified in response to the social and cultural expectations of mainstream culture (Harkness & Super, 2002) via parental acculturation.

Korean Immigrant Families

Korean American families have been found to be distinctly more oriented towards Korean culture than mainstream Western culture, with minimal parental acculturation (Choi & Kim, 2010; I. J. Kim, 2004). Although Korean immigrant parents largely preserve their traditional and core parenting values and behaviors, they also adopt new cultural traits (Choi, et al., 2013). Korean immigrant parents continue to emphasize traditional etiquettes and manners that symbolize the core tradition of respect for elders, including using two hands to hand things to elders, using honorifics for elders. They also maintain traditional parenting practices such as co-sleeping and using indirect expressions of affection. At the same time, they reported decreased use of corporal punishment, as well as lower endorsements of stern parenting and less emphasis on their child’s obedience to parents (Choi, et al., 2013).

How Korean parents’ cultural orientations are specifically associated with traditional family process remains to be investigated. Understanding whether and how bilinear and multidimensional acculturation has any impact on Korean family process, specifically, parenting values and practices, will facilitate new research on the impact of acculturation on heritage family process and related outcomes including youth development.

Indigenous Family Process

The dearth of reliable measures of indigenous family process has been a longstanding obstacle to the understanding of Asian American families (Choi, et al., 2013; Wu & Chao, 2005). Recent research efforts have expanded the inventory of scales that assess nuances of family process among Asian subgroups. For example, the guan and qin parenting measures (Chao, 1994; Wu & Chao, 2011) were developed for Chinese American families. Guan (“to govern/train and love”) and qin (“child’s feeling of closeness to parents or parental benevolence”) encapsulate the idealized Chinese American family process that blends direct control, close monitoring and implicit parental affection via instrumental support, devotion and support for education rather than physical, verbal, emotional expressions. These ideals were shared with Korean Americans and the scales were found to be valid and reliable with them (Choi, et al., 2013). Guan and qin capture aspects of Korean family process, likely because of the two cultures’ shared influence of Confucianism.

Ga-jung-kyo-yuk, translated as “home (or family) education,” is a collection of scales developed specifically for Korean American families that includes measurements of Traditional Korean Parent Virtues, Enculturation of Familial and Cultural Values, and Traditional Korean Etiquettes and Manners that exemplify core ga-jung-kyo-yuk values, such as ideal parenting virtues (e.g., parental role-modeling to teach children the main values), centrality of the family, family hierarchy, age veneration, and family obligations and ties (Choi, et al., 2013). The ga-jung-kyo-yuk scales also include several traditional parenting practices, such as Co-Sleeping with children, which tracks the age at which children started to sleep separately from parents, and Korean Disciplinary Practices (Choi, et al., 2013). Co-sleeping with young children is highly prevalent among Korean families and typically continues well into child’s early elementary school years. While common among many non-Western cultures, thus, not exclusively Korean, co-sleeping was repeatedly suggested by Korean immigrant parents as what they perceive as distinct from the host society and specially used to establish close mother-child bonding. Co-sleeping is thus included as part of ga-jung-kyo-yuk practices (Choi, et al., 2013). Korean Disciplinary Practices measures uniquely Korean corporal disciplinary practices reserved for young children, such as hitting palms or calves with a stick and having children raise their arms or stay on their hands and knees for a prolonged period of time. Each of these corporal punishments has a name with a set of practice rules. The use of this type of corporal punishment usually decreases as children get older. Similar to co-sleeping, corporal punishment is also a common practice in numerous cultures. However, the set of specific practices delineated by Korean Disciplinary Practices is uniquely Korean and is one of ga-jung-kyo-yuk practices.1

Parent Gender

Asian immigrant fathers are infrequently the focus of research, but the importance of the paternal role in family processes has garnered attention in recent years (e.g., Koh, Shao, & Wang, 2009). Emerging scholarship has demonstrated the valuable and often unique contribution fathers make to the family system and the significant influence fathers have on child outcomes (Costigan & Dokis, 2006; Kane & Garber, 2004). Asian American fathers are believed to be less involved than their White counterparts in parenting, and more reserved in parent-child interactions (Pyke, 2000). Indeed, Korean immigrant fathers self-reported more difficulty than mothers in acculturating to American culture and physically and verbally expressing affection to their children, as restricted emotions is a cultural norm for Korean men (Choi & Kim, 2010). In a similar vein, Korean immigrant fathers reported significantly lower parental warmth, acceptance, and communications than mothers (Choi, Kim, Kim, & Park, 2013). When Korean immigrant fathers experienced depression, they were more apt to compromise parental acceptance of their child than mothers in similar situations (E. Kim, 2011). It was postulated that maternal parenting may be less altered by the mother’s psychological state as mothers are more likely to view parenting as a duty.

Conversely, there are studies that contradict the stereotypical images of Korean immigrant fathers. Kim and Rohner (2002) found that, among Korean immigrant families, both paternal and maternal acceptance and involvement equally influenced youth academic achievement, and that fathers were seen as less controlling than mothers. This latter pattern is contrary to the commonly held expectation that Korean fathers are stern, controlling and remote. Rohner and Veneziano (2001) provide empirical evidence that paternal acceptance may be more influential than maternal acceptance in youth development, positively and significantly predicting youth outcomes in all aspects from psychological to behavioral. These somewhat mixed results warrant a closer examination of paternal parenting and, especially, how cultural orientations influence parenting similarly or differently between mothers and fathers.

Present Study

This study investigates how bilinear acculturation in multiple dimensions of culture relates to both core and peripheral elements of traditional family process, i.e., parenting values and parenting practices, among Korean immigrant families. This study discretely but simultaneously examines (1) English competence, (2) engagement in social and cultural activities in host and heritage cultures; and (3) parents’ sense of cultural affiliation and identity to host and heritage cultures. These three areas of cultural orientation have been shown to have distinct roles in Asian American youth and their development (Choi et al., 2017; Choi, Tan, Yasui, & Pekelnicky, 2014) but have been less investigated with parent samples. Korean language competence was not included in this study for lack of variance among samples; all but one parent reported being fluent in Korean. We included the number of years living in the U.S. – the most frequently used proxy of cultural orientation to the host culture – because although most regularly used in the literature, the three dimensions cannot completely explain acculturation. In addition, immigrant parents may adopt or discard certain practices due to laws and sanctions, the influence of which may simply be the function of living longer in the host society.

The indigenous family process measures used in this study are from the ga-jung-kyo-yuk and guan measures and, following Darling and Steinberg’s conceptualization (Darling & Steinberg, 1993), are grouped into parenting values and practices. Parenting values include traditional Korean parent virtues, familial and cultural values used to enculturate Korean youth, traditional Korean manners and etiquettes, and guan ideology. Although manners and etiquettes may be viewed as external behaviors, this measure assesses behaviors that essentially signify the core value of respecting elders in Korean culture and are classified as values in this paper. Parenting practices include co-sleeping, age of separate sleeping, traditional Korean disciplinary practices with young children, and guan practices.

Using the parent data from the Korean American Families (KAF) Project (272 mothers, and 164 fathers, N=436), we hypothesize that parental cultural orientation to the host culture, indicated by English competence, participation in the host culture, and endorsement of American identity, are associated with weaker endorsement of traditional parenting values and behaviors. Conversely, we hypothesize that parental cultural orientation to the heritage culture (i.e., participation in the heritage culture and Korean identity) is related to stronger endorsement of traditional family process variables. We further hypothesize that parenting practices, the peripheral element family process, are more likely to be influenced by the host cultural orientation than parenting values, the core element of family process.

We anticipate two exceptions to our hypotheses. First, regardless of one’s cultural orientations but with a longer residence, Korean immigrant parents may be willing to discard traditional disciplinary practices utilizing corporal punishment that can be considered child abuse in the U.S., as peripheral to their core family process (Choi, et al., 2013). Second, based on a recent study finding that traditional manners and etiquettes among Korean immigrant families may have become a culture-specific code of conduct upheld despite an attenuation of the underlying core values (Choi, Kim, Noh, Lee, & Takeuchi, 2017), we expect traditional Korean manners and etiquette to persist regardless of one’s cultural orientation.

While we intentionally do not postulate gender-specific hypotheses due to the scarcity and inconsistency of available data, we do test our hypotheses across parent gender as an exploratory measure. Comparative analysis across mothers and fathers will add to our understanding of the family socialization process, can provide a springboard for additional investigation, and may lead to a better understanding of the paternal role in influencing youth outcomes. We believe the additional analysis on moderating effect of parent gender will prove to be significant in light of reports of Korean immigrant fathers’ resistance to change and difficulty in acculturation.

Method

Overview of the Project

The Korean American Families Project surveyed 272 mothers and 164 fathers from Korean immigrant families with adolescents living in a Midwest metropolis. The data was longitudinally collected over a two-year period, Time 1 in 2007 and Time 2 in 2008. The family was the sampling unit and the eligibility criteria included Korean family with an early adolescent (i.e., either in middle school -6th through 8th grades - or ages between 11 and 14). Both parents and a youth from each family were asked to participate. Three sources (phonebooks, school rosters and Korean church/temple rosters) were used to recruit survey participants. Samples were obtained from each source in approximately equal proportions. Families from each data source did not differ in age, gender and socio-demographic data. In addition, no significant differences were found between remaining and dropout participants in age, gender and income and parental education. The study procedures were approved by the University of Chicago IRB.

At Time 1, the average ages were 43.4 for mothers (SD = 4.57) and 46.3 for fathers (SD = 4.69) and 12.97 (SD = 1.00) for their children. At Time 1, trained bilingual interviewers conducted in-person interviews. Each member of the family was interviewed separately to protect privacy. At Time 2, the majority of follow-up surveys were completed through self-administered questionnaires. Parents and youth were compensated for participation. Additional details about the data and the study procedures are found elsewhere (Choi, et al., 2013). This study used only the Time 1 data to examine concurrent associations. Time 2 data did not include all measures of parenting values and practices. The additional analyses that we conducted with the available measures in Time 2 data did not add new information. Thus, we focus on Time 1 data only in this paper.

Sample Characteristics

The level of parental education was fairly high: 63.7% of mothers and 70.3% of fathers reported having at least some college education, either in Korea or in the US. Forty-seven percent reported annual household income of 2016 between $50,000 and $99,999. A total of 21% of mothers reported having received public assistance, food stamps, or qualifying for the free/reduced-price school lunch programs, with 15% currently receiving these programs. The characteristics of this sample as urban middle class immigrants with a high proportion of small business owners (over 40%) and Protestants (nearly 77%) are overall similar to the socioeconomic characteristics of Korean immigrants at large (Min, 2006) and fairly comparable to the parent profile in national data such as the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health).

Measures

Response options for items were a 5-point Likert Scale, e.g., (1) “Not at all” (2) “Not much” (3) “Moderately” (4) “Much” and (5) “Very much,” unless noted. Except co-sleeping and the age of separate sleeping arrangement variables, items of the measures were summed to indicate the construct. Three parenting value scales (Traditional Korean parent virtues, Enculturation of familial and cultural values and Traditional Korean manners and etiquettes) as well as one parenting practice scale (Traditional Korean disciplinary practices with young children) were recently developed as parts of Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk family process. Detailed information of the scale development process and psychometric testing [e.g., content and construct validity (including discriminant and convergent validity), factor structure and reliability] was reported in one of the previous issues of this journal (Choi, et al., 2013). This study only used the scales that demonstrated high psychometric properties.

Family Process Constructs (Dependent Variables)

Parenting Values

Traditional Korean parent virtues

Six items were used to assess Korean traditional parenting beliefs including parental virtues and filial piety. Example items include “Parents should try to demonstrate proper attitude and behavior to their children” “Parents should teach their children to respect elders by showing that they love and respect their parents (i.e. children’s grandparents)” and “Parents should make efforts to help children trust parents.” (α = .86)

Enculturation of familial and cultural values

A total of 7 items were constructed to ask parents about the important traditional values that they would like to see in their children when they grow up. Items include supporting siblings and relatives (respectively) when they need help, regarding family as a source of trust and dependence, doing things to please parents, taking care of parents when they get older, maintaining close contacts with family no matter where the child lives, and seriously considering parents’ wishes and advices in career or marriage decisions. (α = .79)

Traditional Korean manners and etiquettes

Several Korean traditional etiquette practices reflect core Korean social traditions and norms. They are identified by Korean immigrant parents as of utmost importance and to be maintained by the next generation. Six items asked parents how important specific behavioral etiquette is to them. Examples include “My child properly greets adults (e.g., bowing to adults with proper greetings).” “My child uses formal (respectful) speech to adults.” “My child keeps Korean social norms and public etiquette in the presence of other adults (e.g., passing things with two hands to adults).” “My child uses correct addressing terms (e.g., calling family members with Korean addressing terms instead of using their first names).” (α = .92)

Guan Parenting Ideology

Guan Parenting Ideology consists of six items that Chao developed to describe socialization goals among Chinese immigrants (Chao, 2000). The items highlight aspects of Chinese parenting that are unique, such as its emphasis on guan, a concept of training and constant care by parents and emphasis on education. The six items include “Parents should train children to work very hard and be disciplined” and “Parents must provide instruction and guidance in order for their children to be successful.” Parents were asked how much these items describe what they believe. (α = .84)

Parenting Practices

Co-sleeping and age of separate sleeping

Co-sleeping with young children is common among Korean families typically up until the early elementary school years, and was identified as something different from the mainstream culture, thus uniquely Korean (though common among Asians) (Choi & Kim, 2010). In our survey, parents were asked whether their child used to sleep with them when s/he was younger. Response options were “Yes” and “No.” If yes, they were asked to specify the age that the child started sleeping separately from parents.

Traditional Korean disciplinary practices with young children

Several disciplinary practices with younger children are identified as uniquely Korean (Choi & Kim, 2010). To assess disciplinary practices with young children, parents were asked whether they used to discipline children when they were younger by hitting the child’s palms or calves with a stick, having the child keep their arms raised for a prolonged period of time, or to specify other methods of discipline, if any. (α = .60)

Guan Parenting

Guan Parenting Behaviors are four items and originally designed to ask children about their parents’ behavior. For our survey, the items were modified to ask parents how much they describe what they do to their child. The questions include “I give more freedom only if my child shows s/he is responsible” and “I only let my child spend time with the friends that I think are a good influence.” These items assess specific parenting behaviors that are derived from guan parenting ideology. (α = .70)

Acculturation Constructs (Independent Variables)

Host Cultural Orientation

Number of years living in U.S

Number of years living in U.S. is one of the most frequently used acculturation proxy variables in the literature and is included in this study’s set of acculturation variables.

English language competence

English language competence is consistently used to assess parents’ level of acculturation and cultural competence. In this study, parents were asked to rate how well they speak, understand, read and write English. (α = .92).

Participation in mainstream culture

Participation in mainstream culture was assessed by nine items, mostly adopted from the language, identify and behavior (LIB) measure (Birman & Trickett, 2002), including how often parents (1) read American books, websites, newspapers, or magazines, (2) listen to American songs, (3) watch American dramas and movies (4) eat American food, (5) attend American clubs or parties, (6) eat at American restaurants, (7) buy groceries in American stores, (8) participate in American holidays and traditions (like Thanksgiving), and (9) have American friends. (α = .85)

American identity

American identity, a sense of affiliation with the host society among parents, was assessed with seven questions (also adopted from the LIB measure). The questions asked the degree to which parents think of oneself as American, feel good about being American, feel part of American culture, have a strong sense of being American and are proud of being American. (α = .91)

Heritage Cultural Orientation

Participation in Korean culture

Participation in Korean culture was assessed by nine modified questions regarding cultural activities parallel to activities in the host culture, i.e., reading Korean books, listening to Korean songs, and watching Korean dramas and movies. These items were summed to indicate the constructs. (α = .82)

Korean identity

Korean identity was assessed by asking parents seven questions that are parallel to those asked of American identity. (α = .88)

Control Variables

A few control variables were included in the analyses to account for possible differences in parenting behaviors by gender, education, and income, all of which have been shown to be related to acculturation.

Analysis Strategy

First, descriptive statistics of main constructs, including means, standard deviations, and pair-wise bivariate correlations were examined with the full sample and also with mothers and fathers separately to identify significant differences by gender of the parent. Second, to examine predictive relationships, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analyses for continuous variables and logistic regression for a binary variable were conducted with acculturation variables as independent variables and parenting constructs as dependent variables. Regressions were modeled in such a way that independent and dependent variables are from the same time point, which identifies concurrent predictors. Three control variables, income, education, and gender measured at Time 1, were included in all regression models. The gender variable was dummy-coded and “mother” was entered as a reference group. Finally, to examine whether the impact of cultural orientations differs by gender of the parent, interaction terms (the product term of independent variables by gender) were created and entered into the regression models. Missing data comprised less than 5% of each data point, at which level missing imputations do not make significant differences in results (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Thus, the analyses were conducted only with complete cases.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1, first for the full sample, and then for mothers and fathers respectively. Overall, the average rate of adaptation to the mainstream culture in term of language proficiency, behavioral engagement, and identity was lower than that of preservation of the culture of origin. For example, the rate of American Identity was 2.35 in 1 to 5 scales while it was 4.01 for Korean Identity. The endorsement of the traditional Korean parenting values and behaviors was high among parents as well, ranging from 4.22 to 4.60, also in 1 to 5 scales. Eighty-two percent of parents reported having co-slept with their children when they were younger and the average child’s age of separate sleeping was 6.42 with a large standard deviation (4.35). Traditional Korean Disciplinary Practices with Young Children was rated low (1.78) but Korean parents’ endorsement of other Asian values and parenting constructs was high ranging from 3.80 (Guan Behaviors) to 4.32 (Guan Ideology).

Table 1.

Mean and Standard Deviation of Main Constructs

| Full Sample | Mothers | Fathers | Significance+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years in US | 15.4 (8.35) | 15.28 (8.33) | 15.60 (8.39) | n.s. |

| English | 3.03 (0.77) | 2.94 (0.74) | 3.18 (0.79) | t= −3.115** |

| Mainstream Culture | 2.80 (0.70) | 2.77 (0.67) | 2.85 (0.76) | n.s. |

| American Identity | 2.35 (0.87) | 2.31 (0.86) | 2.41 (0.90) | n.s. |

| Korean Culture | 3.64 (0.65) | 3.64 (0.65) | 3.63 (0.66) | n.s. |

| Korean Identity | 4.01 (0.70) | 3.98 (0.71) | 4.05 (0.68) | n.s. |

| Parenting Virtues | 4.60 (0.47) | 4.64 (0.44) | 4.53 (0.52) | t = 2.351* |

| Enculturation | 4.22 (0.40) | 4.24 (0.40) | 4.20 (0.40) | n.s. |

| Korean Manners | 4.44 (0.65) | 4.44 (0.64) | 4.45 (0.67) | n.s. |

| Guan Ideology | 4.32 (0.58) | 4.39 (0.56) | 4.20 (0.60) | t = 3.215*** |

| Co-sleeping (%) | 0.82 (0.38) | 0.82 (0.38) | 0.81 (0.39) | n.s. |

| Age of separate sleeping | 6.42 (4.35) | 6.69 (4.47) | 5.97 (4.11) | n.s. |

| Early Disciplines | 1.78 (0.67) | 1.80 (0.63) | 1.75 (0.72) | n.s. |

| Guan Behaviors | 3.80 (0.71) | 3.85 (0.70) | 3.72 (0.72) | n.s. |

Note:

Significance refers to statistically significant differences between mothers and fathers in means, based on paired sample t-tests

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Only a few gender differences were noted in descriptive statistics – fathers reported higher level of English proficiency and mothers reported higher endorsement of Traditional Korean Parenting Virtues (4.64 vs. 5.53, p<.05) and Guan Parenting Ideology (4.39 vs. 4.20, p<.001). The pair-wise bivariate correlations are shown in Table 2. The pattern of correlations was overall as expected with only a few exceptions, e.g., host culture orientation was inversely correlated with heritage culture orientation but positively with guan ideology and behaviors. A longer residence in U.S. was positively correlated with the host culture orientation. A closer examination accounting for controls was conducted with subsequent regression analyses.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix, Mean and Standard Deviation of Main Constructs

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Years in US | 1 | .264** | .333** | .525** | .000 | −.377** | −.097 | −.085 | −.139 | .042 | −.114 | −.157* | −.028 | .074 |

| 2. English | .490** | 1 | .654** | .356** | −.039 | −.050 | .048 | .099 | −.166* | −.073 | .089 | −.030 | .053 | .079 |

| 3. Mainstream Culture | .383** | .507** | 1 | .478** | −.062 | −.093 | .106 | .064 | −.184* | .028 | .078 | .010 | .176* | .173* |

| 4. American Identity | .496** | .409** | .520** | 1 | −.080 | −.437** | −.149 | −.035 | −.197* | .040 | −.134 | −.137 | .007 | .204** |

| 5. Korean Culture | −.070 | −.211** | −.221** | −.203** | 1 | .297** | .244** | .276** | .244** | .338** | .080 | .072 | −.037 | .167* |

| 6. Korean Identity | −.217** | −.185** | −.261** | −.332** | .409** | 1 | .326** | .221** | .339** | .147 | .123 | .045 | .064 | .016 |

| 7. Parenting Virtues | −.073 | −.026 | .034 | −.038 | .145* | .202** | 1 | .352** | .292** | .435** | .201* | .084 | −.024 | .314** |

| 8. Enculturation | .027 | .070 | −.002 | −.064 | .219** | .178** | .367** | 1 | .339** | .445** | .095 | .110 | .127 | .340** |

| 9. Korean Manners | −.131* | −.154* | −.079 | −.126* | .285** | .211** | .185** | .241** | 1 | .331** | .075 | .134 | .144 | .235** |

| 10. Guan Ideology | .047 | .058 | .030 | .069 | .141* | .195** | .395** | .386** | .290** | 1 | .133 | .102 | .024 | .385** |

| 11. Co-sleeping | −.156* | −.141* | −.177** | −.171** | .167** | .121* | −.001 | .049 | .213** | −.011 | 1 | .694** | −.088 | .067 |

| 12. Age of separate sleeping | −.041 | −.128* | −.184** | −.101 | .097 | .022 | .025 | .077 | .154* | .031 | .699** | 1 | −.057 | .154 |

| 13. Early Disciplines | −.140* | −.034 | .046 | −.014 | .061 | .067 | .064 | .103 | .162** | .009 | .131* | .041 | 1 | .213** |

| 14. Guan Behavior | .009 | .138* | .099 | .091 | .057 | .041 | .296** | .164** | .138* | .429** | −.134* | −.070 | .092 | 1 |

Note: Correlations below the diagonal are for mothers; those above are for fathers

p < .05

p < .01

Multivariate Regressions

Regression results are shown in Table 3. The results regarding the association between preservation of heritage culture and indigenous family process variables were consistent and in the expected direction more so than not. Specifically, after accounting for the host cultural orientation and the controls, Participation in Korean Culture positively predicted majority of parenting values and practices, i.e., Traditional Korean Parenting Virtues (β=.115, p<.05), Enculturation of Familial and Cultural Values (β=.207, p<.001), Traditional Korean Manners and Etiquettes (β=.187, p<.01), Guan Ideology (β=.159, p<.01), Co-sleeping (logistic β=.516 (OR 1.675), p<.05), and Guan Behaviors (β=.146, p<.01). Korean Identity was another notable positive predictor, but showing significant and positive associations mainly with parenting values but not parenting practices, i.e., Traditional Korean Parenting Virtues (β=.212, p<.001), Enculturation of Familial and Cultural Values, (β=.109, p<.05) Traditional Korean Manners and Etiquettes (β=.205, p<.001), and Guan Ideology (β=.207, p<.001).

Table 3.

Regression Models of Acculturation Variables Predicting Family Constructs

| Family Process Variables

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting Values | Parenting Practices | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| PREDICTORS | Parenting Virtue | Enculturation | Korean Manners | Guan Ideology | Co-Sleeping (Yes/No)^ | Age of Separate Sleeping | Early Disciplines | Guan Behaviors |

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Income | −.071 | −.077 | −.024 | −.047 | −.098 (.908) | −.037 | −.014 | .001 |

| Education | .045 | .067 | −.049 | −.055 | .338 (1.401)* | .038 | −.033 | −.038 |

| Gender (Ref. = Mother) | −.136** | −.074 | .016 | −.160** | −.006 (.994) | −.074 | .046 | −.114** |

| Acculturation Variables | ||||||||

| Host Cultural Orientation | ||||||||

| Years in US | −.021 | −.005 | −.022 | .038 | −.024 (.976) | −.014 | −.133* | −.075 |

| English Proficiency | .006 | .147* | −.058 | .022 | .070 (1.073) | −.002 | −.049 | .116* |

| Engagement in mainstream | .161* | .026 | −.011 | .045 | −.002 (0.998) | −.058 | .184** | .173 |

| American Identity | −.058 | −.049 | −007 | .121 | −.332 (.717) | −.098 | .039 | .131* |

| Heritage Cultural Orientation | ||||||||

| Engagement in Korean | .115* | .207*** | .187** | .159** | .516 (1.675)* | .104 | .033 | .146** |

| Korean Identity | .212*** | .109* | .205*** | .207*** | .138 (1.148) | −.054 | .046 | .051 |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| English × Father | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Engagement in Main × Father | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 1.979* | n.s. | n.s. |

| American Identity × Father | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Engagement in Korean × Father | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | .220* | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Korean Identity × Father | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| R2 | .114 | .096 | .128 | .110 | .039 | .035 | .066 | |

Notes: Coefficients shown are standardized regression coefficients.

Logistic regression b and odd ratio in parentheses

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

The host culture orientation and its relations to indigenous parenting were mixed with both expected and unexpected associations. The general pattern was that, accounting for heritage cultural orientations and the controls, the host cultural orientation variables, i.e. English Language Competence, Participation in Mainstream Culture, and American Identity, and the number of years living in the U.S., did not predict the majority of indigenous family process variables, i.e., both values and practices. However, there were several exceptions in which the host cultural orientation variables were, contrary to expectation, positively associated with some of the indigenous parenting constructs. For example, in the multivariate models, longer years of living in U.S. predicted less use of Traditional Korean Disciplinary Practices (β=−.113, p<.05), which was expected, but Participation in Mainstream Culture predicted more use of such practices (β=.184, p<.01). Similarly, Participation in Mainstream Culture also predicted higher endorsement of Traditional Korean Parenting Virtue (β=.161, p<.05). Parents’ English Language Competence also predicted a higher rate of Enculturation of Familial and Cultural Values (β=.147, p<.05) and Guan Behaviors (β=.116, p<.05). Lastly, parents’ American Identity predicted more Guan Parenting Behaviors (β=.131, p<.05). Thus, the unexpected relations include those with both parenting values and practices.

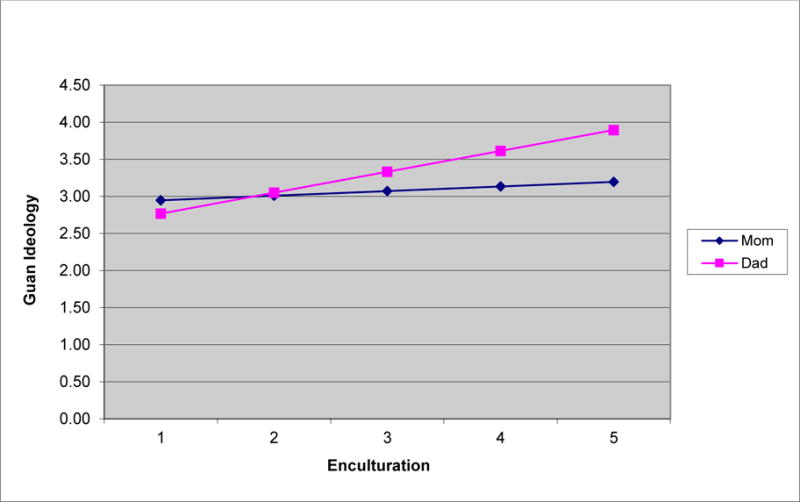

Parent Gender

Only two interaction terms were statistically significant. Participation in Korean Culture was a stronger predictor of Guan Ideology for fathers than for mothers (b=.220, p<.05). In addition, Participation in Mainstream Culture was also a stronger predictor of later age of sleeping separately for fathers than mothers (b=1.979, p<.05). While Participation in Mainstream Culture was a non-significant predictor of Age of Separate Sleeping with a slight negative leaning for mothers, it was a significant and positive predictor for fathers, which means that the more fathers engaged in the mainstream cultural activities, the older their children were when they separated from the family bed. The significant interaction terms are depicted in graphs (Graph 1 and 2)

Graph 1.

Interaction plot of enculturation on guan ideology by parent gender

Discussion

This study investigated the relationships between indigenous family process and bilinear and multidimensional cultural orientations among Korean immigrant parents. The results presented differential associations by distinct cultural orientations, dimensions and core vs. peripheral elements of family process.

Bilinear and Multidimensional Culture Orientation

The findings confirmed our hypothesis that parental orientation towards the heritage culture would be associated with stronger endorsement of traditional family process, but specifically more so with parenting values than practices. Parents who maintained their heritage culture by engaging in Korean cultural activities and endorsing a strong Korean identity preserved much of their traditional culture in family process, and parenting values in particular, even after accounting for their acculturation to the host culture. Notably, Korean identity was predictive of parenting values only and not parenting practices. Racial-ethnic identity is thought to be a much more conscious endorsement of one’s race-ethnicity than the other elements of race-ethnicity (Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, & Wong, 2002). For non-white immigrants, it is a dimension that may persist or in fact be strengthened over time and generations as their awareness and socialization as a racial-ethnic minority is heightened. Its solid and positive relationships with parenting values suggest that core elements of family process, i.e., parenting values, are likely to persevere more so than parenting practices. Indeed, the latter already show a sign of dwindling even among the first generation of immigrant parents.

However, our hypothesis that parental orientation towards mainstream culture would be associated with a limited weaker endorsement of traditional family process values and behavior was only partially confirmed. Parents’ cultural orientation to the mainstream culture overall showed no significant impact on either aspect of indigenous family process, i.e., parenting values and practices, while the use of corporal punishment was negatively associated specifically with length of stay in the U.S. as expected. In fact, after accounting for parental cultural orientation, years living in the U.S. did not predict any indigenous family process other than disciplinary practices. In contrast, discussed further below, engagement in mainstream cultural activities predicted higher (not lower) use of corporal punishment with young children. These nonsignificant relations partly corroborate Ward’s theory (2001) that acculturation in one dimension of culture is independent of acculturation in other dimensions and highlight that immigrant parents may not change their traditional family process merely by the function of years of living in the host society. Rather, changing family process is likely via specific dimensions of acculturation.

Unexpected findings: Signs of reactive retention or bicultural family process?

Our expectation that traditional Korean manners and etiquettes would persist regardless of one’s cultural orientations was confounded when our bivariate analysis revealed that host culture orientations were either not correlated with traditional parental virtues and enculturating children with core values or negatively correlated with emphasizing traditional Korean manners and etiquettes, decreased use of co-sleeping, and an earlier termination of co-sleeping. Interestingly, in multivariate analyses in which parent’s bilinear orientations were simultaneously modeled, parents’ host culture orientation in fact predicted higher endorsement of traditional parental virtues, stronger efforts of enculturating children with core values, and stronger endorsement of practicing guan behaviors. We were surprised to find that parents’ report of greater engagement in mainstream activities was associated with stronger endorsement of corporal punishment. No sign of suppression effect was found in bivariate correlations, suggesting this was not a spurious relationship. Our finding may be an indication that, as parents acculturate to the mainstream, they become more acutely aware of, and possibly distressed by, the cultural differences between heritage and host culture. Parents may react by more strongly emphasizing their heritage culture and making efforts to retain traditional family process even when, as with corporal punishment, they are proscribed by mainstream culture. Immigrant parents commonly express concern over the rapid Americanization in their children (Waters, Ueba, & Marrow, 2007). More investigation is needed into whether a parent’s orientation to mainstream culture actually increases parent’s reactivity to preserve tradition more forcibly, even when such traditions may be harmful or penalized by mainstream culture.

Alternatively, the strength of heritage cultural retention in our study sample of mostly first generation Korean immigrants may have dominated bilinear acculturation such that traditional family process remains strong, even in the presence of host culture orientation. Consistent with the overall premise of this study, it is also possible that although we observed some signs of acculturation to the host culture among Korean immigrant parents such as learning English, participating in the host culture and developing a sense of affiliation with the host country, their acculturation to the host culture may be relatively recent and limited. Any changes in family process, particularly core elements of parenting values, may just take time to emerge, especially in association with host culture orientation. Longitudinal data is necessary to examine how robust these positive associations between host culture orientation and indigenous parenting values remain across several years. Furthermore, future studies on succeeding generations of Korean immigrants in America may uncover different models of family process, as there is less likely to be strong retention of the heritage culture (L. Kim, Knudson-Martin, & Tuttle, 2014).

A notable unexpected finding was that parents’ American identity and engagement in mainstream cultural activities predicted higher guan behaviors. Interestingly, in bivariate correlations, Guan Behaviors were positively correlated with host cultural orientation as well as one heritage cultural orientation variable, and also with many of the other indigenous parenting scales. Though guan was initially proposed as a form of parental involvement that was neither authoritative nor authoritarian, but uniquely Chinese (Chao, 1994), subsequent research (Sorkhabi, 2005) has found guan to be consistent with the authoritative construct. One study on Hong Kong youth found that guan items overlapped with Western concepts of parental warmth and did not have independent predictive power separate from the dimensions of warmth and control (Stewart et al., 1998). Thus, the finding here may corroborate that guan behaviors are consistent with an orientation towards mainstream, Western culture, which is generally associated with authoritative rather than authoritarian parenting. Alternately, it is also plausible that guan behaviors are a measure of a combination of authoritative and authoritarian bicultural family process, in part explaining the findings of this study in which guan behaviors are predicted by both heritage cultural orientation (behavioral engagement in Korean culture) and host cultural orientation (English proficiency and American identity).

Mothers and Fathers

Mothers and fathers did not differ significantly in the predictive power of their cultural orientation, with two exceptions. Paternal engagement in Korean culture was a stronger predictor of guan ideology than maternal engagement, supporting previous findings that fathers, that maintain heritage culture also adhere to traditional values, such as guan ideology, more so than mothers. These findings suggest that fathers may be resistant to change. However, fathers’ engagement in mainstream culture predicted a later termination date of co-sleeping practices. To the extent co-sleeping is a means of affection and indulgence and also practiced in mainstream society, acculturated Korean immigrant fathers may allow longer periods of co-sleeping as a way to ascribe to the leniency and expressive affection they perceive in their White counterparts (Choi & Kim, 2010).

Moreover, although mothers and fathers did not have significantly different means on most indigenous parenting scales, Korean mothers reported a significantly higher endorsement of traditional parenting virtues and guan ideology than Korean fathers. It is possible that more acculturated fathers than acculturated mothers participated in the survey, and it is also possible that Korean fathers are not as traditional as they are typically portrayed. Finally, even if the predictive relations between parents’ cultural orientations and indigenous family process, as well as the means of indigenous parenting practices, were comparable between genders, the mechanisms by which parental cultural orientations influence family process (and subsequently youth development) may differ across mothers and fathers. For example, Kim and her colleagues (2006) found that maternal acculturation is more directly related to adolescent psychological adjustment than that of fathers.

Future Directions and Conclusion

Immigrant families straddle two cultures. Immigrant parents and their American-born, or Americanized, children not only see family life through different cultural lenses, but concepts such as “being Asian” and “being American,” may be understood differently by parents and children (Tsai, Ying, & Lee, 2000). Parents may become resistant to acculturation as their children embrace the new culture, and the resulting acculturation gap may cause distress. Yet, parental resistance to their child’s acculturation may also serve a purpose, as research has shown that children benefit from being raised biculturally (e.g., Chae & Foley, 2010). While parents’ maintenance of the heritage culture may add to parent-child acculturative dissonance and family stress, racial-ethnic socialization may also be a source of strength for the children of immigrants, as well as for the parents and the family system as a whole.

Parenting values and practices are significant predictors of children’s behavioral and developmental outcomes, and understanding the complex bilinear, multidimensional processes of acculturation becomes urgent when immigrant families struggle. This study provided a nuanced examination of acculturation and family processes among Korean immigrant parents. Future research should examine how changes in or preservation of indigenous parenting influences youth development. Parents’ cultural orientations should also be examined for its influence on youth development. For example, parent’s host culture orientation mediates the impact of parenting style on child’s social competence (E. Kim, Han, & McCubbin, 2007). Another study suggests that a parent’s competency in the host culture boosts parental confidence, which in turn enhances parent’s mental health and parent efficacy (Costigan & Korzyma, 2011).

The size of variances explained by the hypothesized models was not large, indicating that there are additional predictors that determine the modification or preservation of indigenous family processes. Further studies are needed to better explain the variances of indigenous family process. An examination of how these indigenous family constructs interact with conventional parenting constructs to influence youth development would be helpful in identifying which cultural traits optimize youth development.

This study aimed to expand a theorized relation between acculturation and family process posited by an influential theory of minority youth development (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Garcia Coll & Pachter, 2002) and by systematically integrating advancement in literature in acculturation and indigenous family process among Asian immigrants. It is one of the few studies that explicitly and simultaneously examine bilinear and multidimensional acculturation, accounting for the influence of host and heritage orientations on one another. This study also helped identify core versus peripheral elements of family process, supporting the notion that parenting values persist longer than parenting practices. With these nuanced and detailed findings, this research may be applied in targeting specific traits or combinations of traits in preventing and treating minority youth difficulties.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

Public Significance Statement.

This study examined how various aspects of parental acculturation influence family process, e.g., parenting values and behaviors, among Korean American families. The findings show that acculturation does not necessarily lead to a change in core parenting values. However, with acculturation, immigrant parents may become more willing to change certain parenting practices, including those practices that are sanctioned by the host society.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. K01 MH069910), a Seed Grant from the Center for Health Administration Studies, a Junior Faculty Research Fund from the School of Social Service Administration and the Office of Vice President of Research and Argonne Laboratory at the University of Chicago, to the first author.

Footnotes

It is plausible that ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures, and parenting value-scales in particular, work well among other Asian subgroups, because they share numerous collectivistic cultural values (e.g., respecting elders and family obligation), much the same way as guan and qin work well among Korean immigrants. In addition, measures of guan, qin and ga-jung-kyo-yuk are similar in that they are a unique combination of both authoritarian and authoritative styles, indicating shared traits. The development of indigenous parenting measures is still in its burgeoning stage and more research is needed to expand the inventory of available scales and to test cross-cultural invariance of measures across subgroups. A recent study (Choi, Park, Lee, Kim, & Tan, 2017) shows that despite sharing an overarching Asian culture, Filipino Americans and Korean Americans are significantly different in the extent to which they preserve indigenous parenting values and practices. The subgroup differences can be significant, yet subtle. For example, the parenting differences between Chinese and Korean immigrants, even if they are meaningful, can be hard to detect in survey items due to their shared East Asian cultural background, hindering discernable empirical evidence.

References

- Benner AD, Kim SY. Experiences of discrimination among Chinese American adolescents and the consequences for socioemotional and academic development. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(6):1682–1694. doi: 10.1037/a0016119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett EJ. The “language, identity, and behavior” (LIB) acculturation measure. Psychology. University of Illinois; Chicago: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Center for American Progress. Who are Korean Americans. 2015 Retrieved from https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/AAPI-Korean-factsheet.pdf.

- Chae MH, Foley PF. Relationship of Ethnic Identity, Acculturation, and Psychological Well-Being Among Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2010;88(4):466–476. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00047.x. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00047.x. Retrieved from . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65:1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: Relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2000;21(2):233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Bae SW. Demography, psychosocial factors, and emotional problems of Korean American adolescents. Adolescence. 2005 Fall;40:533–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim TY, Noh S, Lee JP, Takeuchi D. Culture and Family Process: Measures of Familism for Filipino and Korean American Parents. Family Process. 2017 doi: 10.1111/famp.12322. Available online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim TY, Pekelnicky DD, Kim K, Kim YS. Impact of youth cultural orientations on perception of family process and development among Korean Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2017;23(2):244–257. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS. Acculturation and enculturation: Core vs. peripheral changes in the family socialization among Korean Americans. Korean Journal of Studies of Koreans Abroad. 2010;21:135–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS, Kim SY, Park IJK. Is Asian American parenting controlling and harsh? Empirical testing of relationships between Korean American and Western parenting measures. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2013;4(1):19–29. doi: 10.1037/a0031220. Special Issue titled “Tiger Moms, Asian American Parenting, and Child/Adolescent Well-being in Diverse Contexts”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS, Pekelnicky DD, Kim HJ. Preservation and Modification of Culture in Family Socialization: Development of Parenting Measures for Korean Immigrant Families. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2013;4(2):143–154. doi: 10.1037/a0028772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Park M, Lee J, Kim TY, Tan KPH. Culture and family process: Examination of culture specific family process via development of new parenting measures among Filipino and Korean American families with adolescents. In: Choi Y, Hahm HC, editors. Asian American Parenting: Family Process and Intervention. New York, NY: Springer; 2017. pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Tan KPH, Yasui M, Pekelnicky DD. Race-ethnicity and culture in the family and youth outcomes: Test of a path model with Korean American youth and parents. Race and Social Problems. 2014;6:69–84. doi: 10.1007/s12552-014-9111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Dokis DP. Similarities and differences in acculturation among mothers, fathers, and children in immigrant Chinese families. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:723–741. [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Korzyma CM. Acculturation and adjustment among immigrant Chinese parents: Mediating role of parenting efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(2):183–196. doi: 10.1037/a0021696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Garcia HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Pachter LM. Ethnic and Minority Parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 4. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield PM. Independence and interdependence as developmental scripts: Implications for theory, research, and practice. In: Greenfield PM, Cocking RR, editors. Cross-cultural Roots of Minority Child Development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM. Culture and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 2. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 253–280. [Google Scholar]

- Iceland J, Weinberg D, Hughes L. The residential segregatin of detailed Hispanic and Asian groups in the United States: 1980-2010. Demographic Research. 2014;31(20):593–624. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(3):339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibria N. Becoming Asian American: Second generation Chinese and Korean American identities. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Korean American parental depressive symptoms and parental acceptance-rejection and control. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2011;32(2):114–120. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2010.529239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Cain KC. Korean American adolescent depression and parenting. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2008;21(2):105–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2008.00137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Cain KC, McCubbin MA. Maternal and paternal parenting, acculturation and young adolescent’s psychological adjustment in Korean American families. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2006;19(3):112–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2006.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Han G, McCubbin MA. Korean American Maternal Acceptance-Rejection, Acculturation, and Children’s Social Competence. Family & Community Health. 2007;30:S33–S45. doi: 10.1097/1001.FCH.0000264879.0000288687.0000264832. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/familyandcommunityhealth/Fulltext/2007/04001/Korean_American_Maternal_Acceptance_Rejection,.6.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Rohner RP. Parental warmth, control and involvement in schooling: Predicting academic achievement among Korean American adolescents. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2002;33(2):127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, editor. Korean-Americans: Past, present, and future. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International Corp; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim L, Knudson-Martin C, Tuttle A. Toward Relationship-Directed Parenting: An Example of North American Born Second-Generation Korean-American Mothers and their Partners. Family Process. 2014;53(1):55–66. doi: 10.1111/famp.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JBK, Shao Y, Wang Q. Father, mother and me: Parental value orientations and child self-identity in Asian American immigrants. Sex Roles. 2009;60(7–8):600–610. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche M, Kim C, Hui MK, Joy A. An empirical study of multidimensional ethnic change: The case of the French Candians in Quebec. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 1996;27(1):114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Louie VS. Compelled to excel: Immigration, education, and opportunity among Chinese Americans. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mariño R, Stuart GW, Minas IH. Acculturation of values and behavior: A study of Vietnamese immigrants. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2000 Apr;33:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Min PG. Korean Americans. In: Min PG, editor. Asian Americans: Contemporary trends and issues. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press; 2006. pp. 230–259. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, von Eye A. The acculturation scale for Vietnamese adolescents (ASVA): A bimidemsional perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26(3):202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Kaspar V, Wickarama KAS. Overt and subtle racial discrimination and mental health: Preliminary findings for Asian immigrants. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1269–1274. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.085316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The rise of Asian Americans. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/

- Pew Research Center. Social & Demographic Trends: Korean Americans. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/asianamericans-graphics/koreans/

- Rohner RP, Veneziano RA. The importance of father love: History and contemporary evidence. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5(4):382–405. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham J. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkhabi N. Applicability of Baumrind’s parent typology to collective cultures: Analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(6):552–563. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SM, Rao N, Bond MH, McBride-Chang D, Fielding R, Kennard BD. Chinese dimensions of parenting: Broadening Western predictors and outcomes. Interntional Journal of Psychology. 1998;33:345–358. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH. Expanding the acculturation gap-distress model: An integrative review of research. Human Development. 2010;53(6):313–340. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Chentsova-Dutton Y, Wong Y. Why and how researchers should study ethnic identity, acculturation, and cultural orientation. In: Nagayama Hall GC, Okazaki S, editors. Asian American psychology: The science of lives in context. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Ying YW, Lee PA. The meaning of “being Chinese” and “being American”: Variation among Chinese American young adults. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2000;31(3):302–332. [Google Scholar]

- Ward C. The A, B, Cs of Acculturation. In: Matsumoto D, editor. The Handbook of Culture and Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 411–445. [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC, Ueba R, Marrow H, editors. The new Americans: A guide to immigration since 1965. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Chao RK. Intergenerational cultural conflicts in norms of parental warmth among Chinese American immigrants. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(6):516–523. Retrieved from http://jbd.sagepub.com/content/29/6/516.abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Chao RK. Intergenerational cultural dissonance in parent-adolescent relationships among Chinese and European Americans. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(2):493–508. doi: 10.1037/a0021063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CJ. Age, acculturation, cultural adjustment, and mental health symptoms of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese immigrant youths. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9(1):34–48. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying YW, Lee PA, Tsai JL. Cultural orientation and racial discrimination: Predictors of coherence in Chinese American young adults. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):427–442. [Google Scholar]