Abstract

We report a new distance- and orientation-dependent, all-atom statistical potential derived from side-chain packing, named OPUS-DOSP, for protein structure modeling. The framework of OPUS-DOSP is based on OPUS-PSP, previously developed by us [JMB (2008), 376, 288–301], with refinement and new features. In particular, distance or orientation contribution is considered depending on the range of contact distance. A new auxiliary function in energy function is also introduced, in addition to the traditional Boltzmann term, in order to adjust the contributions of extreme cases. OPUS-DOSP was tested on 11 decoy sets commonly used for statistical potential benchmarking. Among 278 native structures, 239 and 249 native structures were recognized by OPUS-DOSP without and with the auxiliary function, respectively. The results show that OPUS-DOSP has an increased decoy recognition capability comparing with those of other relevant potentials to date.

Keywords: protein structure prediction, empirical potential function, protein folding, decoy recognition, side-chain packing

Introduction

In protein structure prediction, one of the most challenging tasks is the design of potential functions that can guide the search and identification of possible solutions. Theoretically, we could calculate the energy function via quantum mechanics [1]. However, this method is only possible for small molecules and fails on large systems such as proteins in solvent. Therefore, we need to approximate the energy function. Currently, there are two classes of potentials. One is physics-based potentials including all-atom molecular mechanics force-fields [2–6] and coarse-grained potentials such as MARTINI [7], UNRES [8,9], and OPEP [10]. The other class is knowledge-based potentials [11–20] derived from statistical analysis of known protein structures, which often out-perform physics-based potentials [11,15–18,20,21]. In general, knowledge-based potentials can also be constructed at coarse-grained residue level [18,22–34] or at all-atom level [35–44]. The use of physics-based and knowledge-based models in protein folding is most recently discussed in a comprehensive review [45].

OPUS-Cα potential [27] is an example of knowledge-based coarse-grained models, which only uses the positions of Cα atom as input and significantly reduces the computing cost. Two important issues are involved in knowledge-based potentials, distance dependence, and orientation dependence. For example, DFIREisa distance-dependent all-atom potential that is established on a new reference state called the distance-scaled, finite ideal-gas reference (DFIRE) state [41]. By introducing polar atom interactions (dipoles), DFIRE potential was modified to dDFIRE potential [44]. The RWplus potential incorporates side-chain orientation dependence to all-atom, distance-dependent potential with reference state generated by random walk theory [42]. More recently, based on DFIRE, the GOAP potential is a generalized orientation- and distance-dependent all-atom potential [39].

The orientation dependence is a very important and challenging problem in the development of statistical potential. Many attempts have been made in the literature [18,26–29,33,34,39,40,42–44]. Also, hydrogen bonding influences orientation patterns [46,47]; this effect is included implicitly in this work. A milestone is the OPUS-PSP potential, which is an orientation-dependent statistical all-atom potential derived from side-chain packing [40]. In OPUS-PSP, a protein is described by 19 types of rigid-body block. The relative orientation between each block, extracted from the atomic coordinates, measures the side-chain packing properties. This is important because all-atom potentials typically ignore the heterogeneous chemical bond connectivity [48], and residue-based potentials insufficiently describe side-chain packing due to coarse graining. OPUS-PSP bridges the gap between them [40,49].

In this work, based on the framework of OPUS-PSP [40], we developed a distance- and orientation-dependent, all-atom statistical potential derived from side-chain packing, named OPUS-DOSP. The following changes are implemented. First, some of 19 rigid-body blocks were changed. Second, a distance term was introduced into the potential. Furthermore, in the potential function, we added an auxiliary function to the conventional logarithmic Boltzmann term. This is for adjusting the contributions from the extreme cases in which the “observation” and “reference” differ significantly. In testing on 11 commonly used decoy sets, OPUS-DOSP successful identified 239 and 249 out of 278 native structures, without and with the auxiliary function, respectively. Thus, the ability of OPUS-DOSP to distinguish between native and non-native structures has significantly exceeded the performance of all existing potentials. OPUS-DOSP promises to be an invaluable tool for protein modeling and structure prediction.

Methods

Definitions of 19 rigid-body blocks, relative orientation, and relative distance

In OPUS-DOSP, the definition of relative orientation, and geometry of 19 rigid-body blocks are basically identical to OPUS-PSP [40], but with some modifications. The details of these modifications are given in Supplemental Materials. Briefly, the relative orientation bins remain almost unchanged, but the local symmetry of bins is simplified. Specifically, we assign bins that are symmetric about π with the same local symmetry, and this approach significantly reduces the bins we need to consider.

The new distance term we introduced is defined by the distance between the origin points (defined in Supplemental Materials) of the two rigid-body blocks.

The orientation term in OPUS-DOSP

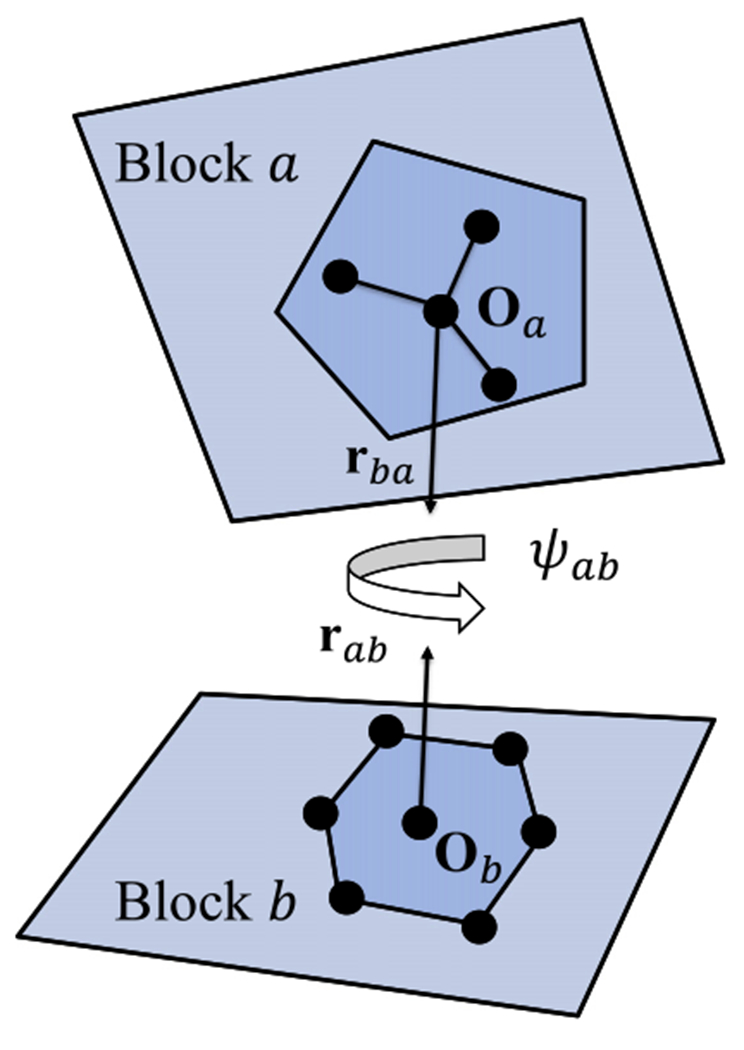

The orientation specifying packing patterns in DOSP potential is also identical to OPUS-PSP potential [40]. As shown in Fig. 1, the relative orientation between block a and b is defined by Ωab, which contains three parts, two relative direction vectors rab and rba between origin points of the two blocks, and an inter-rotation angle ψab along the axis.

Fig. 1.

The definition of relative orientation. Assuming block types a and b are in contact, then rab and rba are the relative direction vectors of block types a and b, and ψab is the inter-rotation angle along the axis connecting the origin point Oa and Ob of the two blocks.

The Boltzmann term of orientation in DOSP is defined by relation:

| (1) |

The term pobs(a, b, Ωab) is the probability of a specific orientation state Ωab for a contact block pair a and b, defined as . Here Nobs(a, b, Ωab) is the number of observed orientation state Ωab for that contact pair, and . The term pref(a, b, Ωab) is the probability of a specific orientation state Ωab for a contact block pair a and b in reference state. Similarly, it is defined as , with Nref(a, b, Ωab) ≡ p(rab)p(rba)p(ψab)Nobs(a, b, Ωab). Here p(rab) is the probability of total contact pairs that have relative direction vectors rab in all contact block pair a and b. The definition of p(rba), p(ψab) are similar. . In the reference state, we consider rab, rba, ψab as independent variables, which is different from the OPUS-PSP potential. The reference state for the orientation is assumed to be a uniform distribution as an approximation. In OPUS-PSP [40], we used a self-excluding Monte Carlo simulation to generate a non-uniform distribution, but the performance was not significantly improved.

The distance term of OPUS-DOSP

The Boltzmann term of distance in DOSP is defined by relation:

| (2) |

pobs(a, b, r) is the probability of a specific distance r for a contact block pair a and b, defined as . Here Nobs(a, b, r) is the number of observed distance state r for that contact pair, and . The term pref(a, b, r) is the probability of a specific distance r for a contact block pair a and b in reference state defined as . In this work, two blocks are defined as in contact if at least one pair of atoms is less than 5 Å. Nref(a, b, r) is the number of a specific distance r between contact block pair of a and b in reference state. In this work, we choose a uniform distribution:

| (3) |

where p(a,b) follows quasi-chemical approximation p(a, b) ≈ XaXb and Xa is the molar fraction of block type a and . The cutoff distance of rcut is set to 15 Å, and Δr is 2 Å for r < 2 Å, 0.5 Å for 2 Å< r <8 Å, and 1 Å for 8 Å < r < 15 Å, which is similar to DFIRE [41]. In modeling the distance interaction between blocks, all blocks are treated as points. The reference state is assumed to have a uniform distribution in order to use quasi-chemical approximation [24].

The OPUS-DOSP potential

In OPUS-DOSP, the contributions of orientation and distance terms vary in different distance range. When the distance between two contacting blocks is either short (less than r1=3.7 Å) or long (larger than r2=10 Å), we only use the orientation term. This is because in the short distance case, the packing between blocks is more sensitive to the relative orientation between blocks, while in the long distance case, the effect of distance dependence maximizes. On the other hand, when the distance falls between r1 and r2, we only use the distance term.

Presumably, there could be a possibility that orientation and distance terms act collectively in different distant ranges. In this work, we only use one energy term in each distance range to avoid the need for optimizing the weight function.

Another feature in OPUS-DOSP is that we excluded all of the contact pairs connected by chemical bonds, which happen only in intra-residue pairs.

The auxiliary function in OPUS-DOSP

Almost all empirical potentials are established based on Boltzmann formula:

| (4) |

where kBT is the Boltzmann constant and temperature, pobs is the probability of specific contact pattern in the observed state, and pref is the probability of specific contact pattern in the reference state. In this study, we found that this relation may underestimate the influence of extreme cases. This is because the non-redundant structure database we used to construct, the potential is of a limited size, which makes the population of packing patterns in that database deviate from Boltzmann distribution due to limited sampling. The consequence for the limited sampling of packing pattern is that the extreme cases, where the ratio of pobs/pref is very large (extremely favorable cases) or very small (extremely unfavorable cases), can produce more reliable results, and we want to raise the weight of these cases in energy construction. Therefore, we add an auxiliary function to the original Boltzmann relationship to increase the weight of extreme cases. This auxiliary function, illustrated in Fig. 2, is

| (5) |

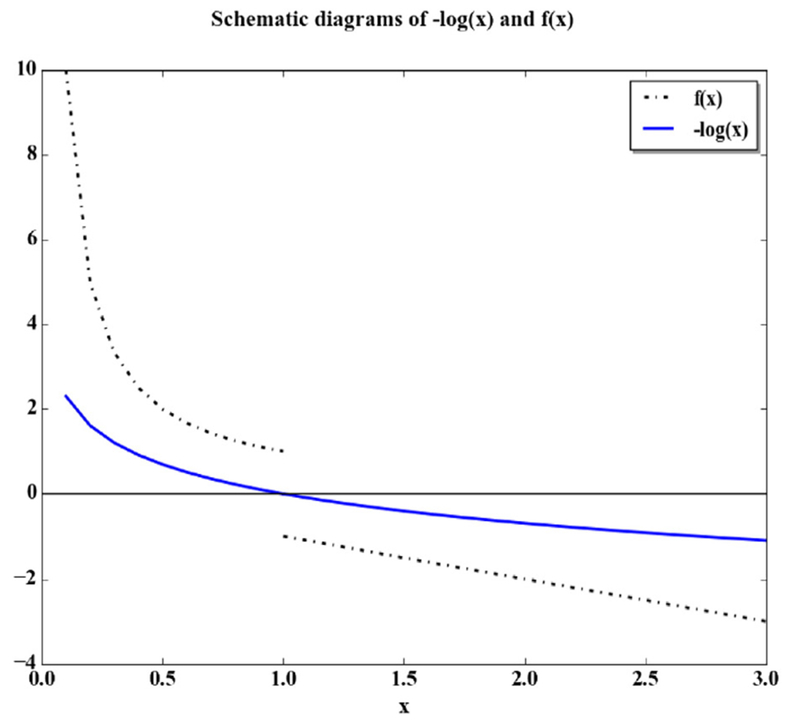

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagrams of −log(x) and f(x). When x is not close to 1, the difference between −log(x) and f(x) is obvious. In the case of x> 1, the linear auxiliary function decays faster than the logarithmic function, making the energy more favorable for larger x. In the case of x< 1, the anti-proportional function increases faster than the logarithmic function, making the energy less favorable for smaller x.

In the case of x> 1, the linear auxiliary function decays faster than the logarithmic function, making the energy more favorable for larger x; while in the case of x<1, the anti-proportional function increases faster than the logarithmic function, making the energy less favorable for smaller x We further illustrate the action of the auxiliary function in Supplemental Materials.

In the implementation of DOSP, the distance term and orientation term are given as

In practice, we set up energy cutoffs to avoid individual extreme values. If the ratio between pobs and pref is smaller than 1/s or larger than s, we set the ratio to 1/s or s, respectively. In this study, the optimal value of s is set to be 55. This result can be derived from the logarithm result, and the detailed process is shown in Supplemental Materials.

We also tested a continuous version of the auxiliary function, which, however, did not significantly improve the results (see Supplemental Materials).

Training set and tested decoy sets

We used the same 1011 proteins as in GOAP potential [39] to train our potential. OPUS-DOSP was then tested on the same 11 decoy sets as used by GOAP, including 4state_reduced [50], Fisa [51], fisa_casp3 [51], hg_structal, ig_structal and ig_structal_hires (R. Samudrala, E. Huang, and M. Levitt, unpublished), I-TASSeR [42], lattice_ssfit [52,53], Lmds [54], MOULDER [55], and ROSETTA [56].

Results

Decoy structure recognition

We compared the performance of OPUS-DOSP with other potentials on the same 11 decoy sets also used for testing the GOAP potential [39]. The results of OPUS-PSP potential, GOAP potential, and OPUS-DOSP potential are presented in Table 1. Of the total of 278 targets in these decoy sets, OPUS-PSP and GOAP were able to recognize 189 and 226 native structures from their decoy structures, respectively. Strikingly, OPUS-DOSP successfully recognized 239 and 249 native structures from their decoys, respectively, without the auxiliary function (DOSP Boltzmann) or with the auxiliary function (DOSP) (Table 1). Comparing to OPUS-PSP and GOAP, DOSP Boltzmann significantly outperformed in six decoy sets (Fisa, hg_structal, ig_structal, ig_structal_ hires, I-TASSER, and Lmds). Both forms of DOSP potential have a better performance on most decoy sets, especially in three homology modeling sets (hg_structal, ig_structal, and ig_structal_hires). The addition of the auxiliary function most significantly improved the overall performance of DOSP in ROSETTA by recognizing 17 more native structures!

Table 1.

The performance of different potentials on the 11 decoy sets

| Decoy sets | Numbers of targets | PSP | GOAP | DOSP (Boltzmann) | DOSP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4state reduced | 7 | 7(−4.41) | 7(−4.31) | 5(−4.26) | 3(−4.03) |

| Fisa | 4 | 3(−4.07) | 3(−3.94) | 4(−5.12) | 2(−3.77) |

| fisa_casp3 | 5 | 5(−6.22) | 5(−5.16) | 4(−4.33) | 4(−4.40) |

| hg_structal | 29 | 18(−1.75) | 22(−1.98) | 25(−3.25) | 27(−3.35) |

| ig_structal | 61 | 22(−1.06) | 47(−1.53) | 61(−6.91) | 61(−7.08) |

| ig_structal_hires | 20 | 15(−1.58) | 18(−1.82) | 20(−4.20) | 20(−4.24) |

| I-TASSER | 56 | 45(−3.46) | 45(−4.99) | 56(−5.55) | 51(−4.97) |

| lattice_ssfit | 8 | 8(−6.52) | 8(−8.53) | 5(−4.56) | 3(−4.46) |

| Lmds | 10 | 8(−5.2) | 7(−3.54) | 10(−5.81) | 10(−7.43) |

| MOULDER | 20 | 19(−4.62) | 19(−3.48) | 15(−2.99) | 17(−4.25) |

| ROSETTA | 58 | 39(−3.17) | 45(−3.39) | 34(−2.93) | 51(−4.16) |

| Total | 278 | 189(−2.87) | 226(−3.27) | 239(−4.67) | 249(−5.01) |

The numbers of targets, with their native states successfully recognized by various potentials, are listed. The numbers in parentheses are the average Z-scores of the native structures. The results suggest that OPUS-DOSP significantly outperforms OPUS-PSP and GOAP potentials in decoy set recognition in terms of both the overall number of native structures recognized and Z-scores. Meanwhile, OPUS-DOSP with auxiliary function (column: DOSP) outperforms the case with Boltzmann term alone (column: DOSP (Boltzmann)).

Distance-dependent and orientation-dependent contributions

In our OPUS-DOSP potential, we first tested whether the inclusion of both the distance-dependent and orientation-dependent contributions in a contact-range-dependent fashion would improve the performance. The results for OPUS-DOSP performance using orientation contribution alone, distance contribution alone, and contact-range-dependent combination of the two are shown in Table 2. Cases with and without the auxiliary function in energy construction are both shown. Clearly, contact-range-dependent combination has far better performance than orientation or distance alone with (DOSP) and without auxiliary function (DOSP Boltzmann). Furthermore, the addition of the auxiliary function in DOSP resulted in consistent better performance than without (DOSP Boltzmann). Thus, the rightmost column in Table 2, the case with contact-range-dependent combination and auxiliary function in energy function, has the very best performance (249 in decoy recognition and −5.01 in Z-score).

Table 2.

The performance of various forms of OPUS-DOSP on the 11 decoy sets

| Decoy sets | Number of targets | DOSP (Boltzmann) |

DOSP |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation alone | Distance alone | Orientation and distance | Orientation alone | Distance alone | Orientation and distance | ||

| 4state_reduced | 7 | 4(−2.97) | 3(−3.46) | 5(−4.26) | 6(−4.32) | 2(−2.26) | 3(−4.03) |

| Fisa | 4 | 2(−1.37) | 3(0.007) | 4(−5.12) | 1(−1.29) | 3(−2.96) | 2(−3.77) |

| fisa_casp3 | 5 | 1(−1.79) | 2(3.42) | 4(−4.33) | 2(−2.19) | 1(−1.57) | 4(−4.40) |

| hg_structal | 29 | 17(−1.18) | 20(−2.34) | 25(−3.25) | 10(−0.95) | 23(−2.85) | 27(−3.35) |

| ig_structal | 61 | 52(−3.57) | 61(−6.54) | 61(−6.91) | 50(−3.08) | 61(−7.02) | 61(−7.08) |

| ig_structal_hires | 20 | 19(−3.38) | 20(−4.13) | 20(−4.20) | 19(−3.10) | 20(−4.23) | 20(−4.24) |

| I-TASSER | 56 | 50(−5.55) | 44(−4.06) | 56(−5.55) | 44(−4.41) | 51(−4.43) | 51(−4.97) |

| lattice_ssfit | 8 | 6(−4.27) | 6(−1.79) | 5(−4.56) | 4(−2.90) | 7(−3.82) | 3(−4.46) |

| Lmds | 10 | 6(−2.74) | 8(−2.03) | 10(−5.81) | 7(−3.76) | 8(−4.03) | 10(−7.43) |

| MOULDER | 20 | 13(−2.53) | 11(−0.58) | 15(−2.99) | 17(−3.12) | 14(−2.94) | 17(−4.25) |

| ROSETTA | 58 | 16(−1.22) | 5(4.48) | 34(−2.93) | 34(−2.50) | 4(2.80) | 51(−4.16) |

| Total | 278 | 186(−3.11) | 183(−1.98) | 239(−4.67) | 194(−3.01) | 194(−3.04) | 249(−5.01) |

The numbers of targets, with their native states successfully recognized by various forms of DOSP, are listed. The numbers in parentheses are the average Z-scores of the native structures. In both cases (DOSP Boltzmann and DOSP), the consideration of orientation and distance contributions based on contact distance range (the third column in each case) results in a better performance than the cases in which orientation or distance contributions are considered alone.

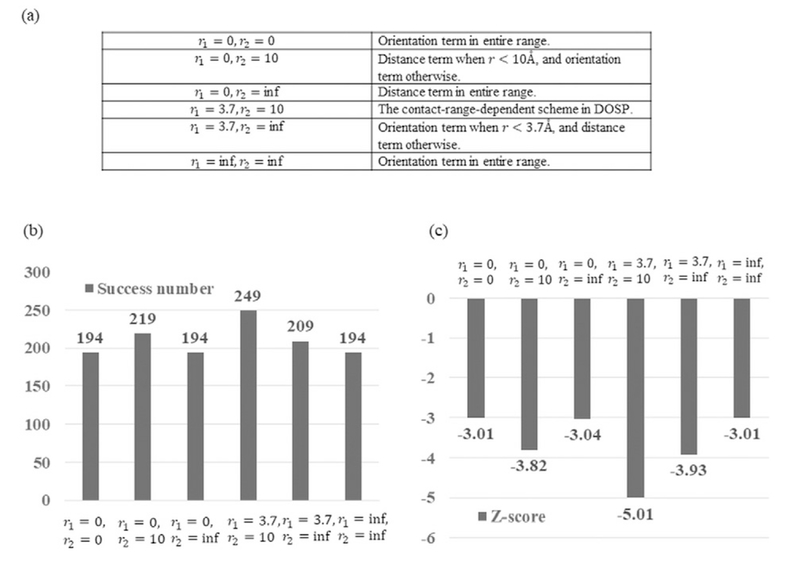

To test the effect of the two cutoff distances r1 and r2, we examined the performance in the cases that each of the cutoff distance was set to zero, original value used in OPUS-DOSP (r1 = 3.7 Å and r2 = 10 Å), or infinite. The results are shown in Fig. 3. It is clear that the values of r1 = 3.7 Å and r2 = 10 Å as used in OPUS-DOSP produced the best results than all other combinations.

Fig. 3.

The performance of OPUS-DOSP with different cut-off values on 11 decoy sets. (a) Explanation of the tested scenarios. (b) The total number of native structures successfully recognized in the 11 decoy sets. (c)The mean Z-scores in the 11 decoy sets.

Discussion

In OPUS-PSP potential [40], only the orientation of 19 rigid-body blocks are considered, while in OPUS-DOSP, we have considered both the orientation- and distance-dependent contributions. The two types of energy contributions are applied separately in different contact distance range. Since some blocks make more extensive physical contacts than the others depending on the packing pattern, for simplicity, we used the distance between the origins of two contacting blocks as a parameter to distinguish the packing pattern. We assume that when two contacting blocks are in close distance (distance <3.7 Å), the orientation contribution dominates. This is because, in close distance, the two blocks are likely to have more extensive physical contacts and the main freedoms to change between the two blocks are those of relative orientation rather than distance between them. Thus, we only consider the orientation contribution in this shortest distance range.

When the distance between two blocks is in the intermediate range (3.7 Å < distance < 10 Å), the physical contact between two blocks has larger variation. In this case, distance term seems to be more sensitive than the orientation term. We therefore only consider the distance term energy function.

When the distance between two blocks is large (distance > 10 Å), the two blocks need to be positioned in a specific angle in order to have one or a few atomic contacts; therefore, the orientation term is again sensitive. We thus only use orientation contribution in this case.

Although we only consider one energy term in a particular contact distance range, it is possible that both types of energy contributions act collectively. In this work, we did not combine the two together in the same contact distance range so as to avoid the complication of optimizing the relative weight between them. These two contributions are not exactly orthogonal to each other, and future work will be focused on optimal combination of them.

In OPUS-DOSP, we added an auxiliary function to the Boltzmann formula in the energy construction. The conventional Boltzmann formula may underestimate the impact of extreme cases due to the limited size of non-redundant structural dataset used for constructing the potential. No explicit weighting parameter is included between the auxiliary function and Boltzmann function. We did not observe significant improvement of performance by adjusting the weight of the two during our investigation.

OPUS-DOSP potential is termed as an all-atom potential because it requires input of all atom coordinates. However, its construction is also coarse-grained in nature as the orientation dependence is described by the 19 blocks, rather than individual atoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

J.M. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM067801, R01-GM116280) and the Welch Foundation (Q-1512). Q.W. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AI067839, R01-GM116280), the Gillson–Longenbaugh Foundation, and The Welch Foundation (Q-1826).

Abbreviations used:

- PSP

potential based on side-chain packing

- DOSP

distance- and orientation-dependent potential derived from side-chain packing

- DFIRE

distance-scaled, finite ideal-gas reference state

- RW

random walk

- GOAP

generalized orientation- and distance-dependent all-atom potential

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2017.08.013.

References

- [1].Senn HM, Thiel W, QM/MM methods for biomolecular systems, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (2009) 1198–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].MacKerell AD Jr., Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL Jr., Evanseck JD, Field MJ, et al. , All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins†, J. Phys. Chem. B 102 (1998) 3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M, CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations, J. Comput. Chem. 4 (1983) 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Weiner SJ, Kollman PA, Nguyen DT, Case DA, An all atom force field for simulations of proteins and nucleic acids, J. Comput. Chem. 7 (1986) 230–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Case DA, Cheatham TE, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, et al. , The Amber biomolecular simulation programs, J. Comput. Chem. 26 (2005) 1668–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Arnautova YA, Jagielska A, Scheraga HA, A new force field (ECEPP-05) for peptides, proteins, and organic molecules, J. Phys. Chem. B 110 (2006) 5025–5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marrink SJ, Risselada HJ, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, De Vries AH, The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations, J. Phys. Chem. B 111 (2007) 7812–7824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liwo A, Ołdziej S, Pincus MR, Wawak RJ, Rackovsky S, Scheraga HA, A united-residue force field for off-lattice protein-structure simulations. I. Functional forms and parameters of long-range side-chain interaction potentials from protein crystal data, J. Comput. Chem. 18 (1997) 849–873. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liwo A, Pincus MR, Wawak RJ, Rackovsky S, Ołdziej S, Scheraga HA, A united-residue force field for off-lattice protein-structure simulations. II. Parameterization of short-range interactions and determination of weights of energy terms by Z-score optimization, J. Comput. Chem. 18 (1997) 874–887. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chebaro Y, Pasquali S, Derreumaux P, The coarse-grained OPEP force field for non-amyloid and amyloid proteins, J. Phys. Chem. B 116 (2012) 8741–8752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Skolnick J, In quest of an empirical potential for protein structure prediction, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16 (2006) 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sippl MJ, Knowledge-based potentials for proteins, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5 (1995) 229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jernigan RL, Bahar I, Structure-derived potentials and protein simulations, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6 (1996) 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Moult J, Comparison of database potentials and molecular mechanics force fields, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 (1997) 194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lazaridis T, Karplus M, Effective energy functions for protein structure prediction, Curr.Opin.Struct.Biol. 10 (2000) 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gohlke H, Klebe G, Statistical potentials and scoring functions applied to protein–ligand binding, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11 (2001) 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Russ WP, Ranganathan R, Knowledge-based potential functions in protein design, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12 (2002) 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Buchete N, Straub J, Thirumalai D, Development of novel statistical potentials for protein fold recognition, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14 (2004) 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Poole AM, Ranganathan R, Knowledge-based potentials in protein design, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16 (2006) 508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhou Y, Zhou H, Zhang C, Liu S, What is a desirable statistical energy functions for proteins and how can it be obtained? Cell Biochem. Biophys. 46 (2006) 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bradley P, Malmström L, Qian B, Schonbrun J, Chivian D, Kim DE, et al. , Free modeling with Rosetta in CASP6, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf 61 (2005) 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Miyazawa S, Jernigan RL, Estimation of effective interresidue contact energies from protein crystal-structures—quasi-chemical approximation, Macromolecules 18 (1985) 534–552. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hendlich M, Lackner P, Weitckus S, Floeckner H, Froschauer R, Gottsbacher K, et al. , Identification of native protein folds amongst a large number of incorrect models: the calculation of low energy conformations from potentials of mean force, J. Mol. Biol. 216 (1990) 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sippl MJ, Calculation of conformational ensembles from potentials of mena force: an approach to the knowledge-based prediction of local structures in globular proteins, J. Mol. Biol. 213 (1990) 859–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jones DT, Taylort W, Thornton JM, A new approach to protein fold recognition, Nature 358 (1992) 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gilis D, Biot C, Buisine E, Dehouck Y, Rooman M, Development of novel statistical potentials describing cation–π interactions in proteins and comparison with semiempirical and quantum chemistry approaches, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 46 (2006) 884–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu Y, Lu M, Chen M, Li J, Ma J, OPUS-Ca: a knowledge-based potential function requiring only Cα positions, Protein Sci. 16 (2007) 1449–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hoppe C, Schomburg D, Prediction of protein thermostability with a direction-and distance-dependent knowledge-based potential, Protein Sci. 14 (2005) 2682–2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang Y, Kolinski A, Skolnick J, TOUCHSTONE II: a new approach to ab initio protein structure prediction, Biophys. J. 85 (2003) 1145–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Koliński A, Bujnicki JM, Generalized protein structure prediction based on combination of fold-recognition with de novo folding and evaluation of models, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf 61 (2005) 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Skolnick J, Kolinski A, Ortiz A, Derivation of protein-specific pair potentials based on weak sequence fragment similarity, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf 38 (2000) 3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tobi D, Elber R, Distance-dependent, pair potential for protein folding: results from linear optimization, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf 41 (2000) 40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Buchete N-V, Straub J, Thirumalai D, Continuous anisotropic representation of coarse-grained potentials for proteins by spherical harmonics synthesis, J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 22 (2004) 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Buchete N-V, Straub J, Thirumalai D, Orientation-dependent coarse-grained potentials derived by statistical analysis of molecular structural databases, Polymer 45 (2004) 597–608. [Google Scholar]

- [35].DeBolt SE, Skolnick J, Evaluation of atomic level mean force potentials via inverse folding and inverse refinement of protein structures: atomic burial position and pairwise non-bonded interactions, Protein Eng. 9 (1996) 637–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang C, Vasmatzis G, Cornette JL, DeLisi C, Determination of atomic desolvation energies from the structures of crystallized proteins, J. Mol. Biol. 267 (1997) 707–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Samudrala R, Moult J, An all-atom distance-dependent conditional probability discriminatory function for protein structure prediction, J. Mol. Biol. 275 (1998) 895–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lu H, Skolnick J, A distance-dependent atomic knowledge-based potential for improved protein structure selection, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf 44 (2001) 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhou H, Skolnick J, GOAP: a generalized orientation-dependent, all-atom statistical potential for protein structure prediction, Biophys. J. 101 (2011) 2043–2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lu M, Dousis AD, Ma J, OPUS-PSP: an orientation-dependent statistical all-atom potential derived from side-chain packing, J. Mol. Biol. 376 (2008) 288–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhou H, Zhou Y, Distance-scaled, finite ideal-gas reference state improves structure-derived potentials of mean force for structure selection and stability prediction, Protein Sci. 11 (2002) 2714–2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhang J, Zhang Y, A novel side-chain orientation dependent potential derived from random-walk reference state for protein fold selection and structure prediction, PLoS One 5 (2010), e15386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].My Shen A Sali, Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures, Protein Sci. 15 (2006) 2507–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yang Y, Zhou Y, Specific interactions for ab initio folding of protein terminal regions with secondary structures, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf 72 (2008) 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kmiecik S, Gront D, Kolinski M, Wieteska L, Dawid AE, Kolinski A, Coarse-grained protein models and their applications, Chem. Rev 116 (2016) 7898–7936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kortemme T, Morozov AV, Baker D, An orientation-dependent hydrogen bonding potential improves prediction of specificity and structure for proteins and protein–protein complexes, J. Mol. Biol. 326 (2003) 1239–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Morozov AV, Kortemme T, Potential functions for hydrogen bonds in protein structure prediction and design, Adv. Protein Chem. 72 (2005) 1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen WW, Shakhnovich EI, Lessons from the design of a novel atomic potential for protein folding, Protein Sci. 14 (2005) 1741–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ma J, Explicit orientation dependence in empirical potentials and its significance to side-chain modeling, Acc. Chem. Res. 42 (2009) 1087–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Park B, Levitt M, Energy functions that discriminate X-ray and near-native folds from well-constructed decoys, J. Mol. Biol. 258 (1996) 367–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Simons KT, Kooperberg C, Huang E, Baker D, Assembly of protein tertiary structures from fragments with similar local sequences using simulated annealing and Bayesian scoring functions, J. Mol. Biol. 268 (1997) 209–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Samudrala R, Xia Y, Levitt M, Huang E, A combined approach for ab initio construction of low resolution protein tertiary structures from sequence, Pac. Symp. Biocomput (1999) 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Xia Y, Huang ES, Levitt M, Samudrala R, Ab initio construction of protein tertiary structures using a hierarchical approach, J. Mol. Biol. 300 (2000) 171–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Keasar C, Levitt M, A novel approach to decoy set generation: designing a physical energy function having local minima with native structure characteristics, J. Mol. Biol. 329 (2003) 159–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].John B, Sali A, Comparative protein structure modeling by iterative alignment, model building and model assessment, Nucleic Acids Res. 31 (2003) 3982–3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Tsai J, Bonneau R, Morozov AV, Kuhlman B, Rohl CA, Baker D, An improved protein decoy set for testing energy functions for protein structure prediction, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf 53 (2003) 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.